CINEREOUS VULTURES

Cinereous vultures (Aegypius monachus) are also known as black vultures, Eurasian black vultures and monk vultures. They are very large birds of prey distributed through much of temperate Eurasia. With a body length of 1.2 meters (3.9feet) and a wingspan of 3.1 meters (10 feet) across the wings and a maximum weight of 14 kilograms (31 pounds), they are the largest Old World vulture and largest member of the family Accipitridae. Cinereous vultures have relatively long lifespan for a bird — 40 years in captivity.. They can live at least 20 years old in the wild but require large areas and suitable food sources to thrive. [Source: Wikipedia, Katharine Barbeiro, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Cinereous vultures are raptors like hawks, eagles and owls. The genus name Aegypius is a Greek word for 'vulture', or a bird not unlike one. The Roman scholar Aelian (A.D. 175–235) describes the aegypius as "halfway between a vulture (gyps) and an eagle”, which is not a bad description for Cinereous vultures as they do have eagley characteristics. But as vultures they specialize in eating carcasses, which in turn reduces the spread of diseases. As carrion eaters, Cinereous vultures are exposed to many pathogenss. A 2015 study of their gastric and immune defense systems conducted sequenced the bird's entire genome and found positively selected genetic variations associated with respiration and the ability of the vulture's immune defense responses and gastric acid secretion to digest carcasses.

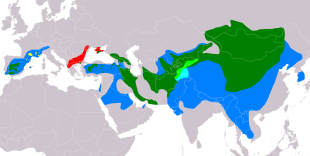

Cinereous vultures breed throughout much of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia including Spain, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Ukraine, Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran, Afghanistan, northern India, northern Pakistan, Mongolia, and mainland China. They also winter in areas of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa including the Sudan, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, northwest India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Laos, North Korea, and South Korea.

Cinereous vultures prefer hilly mountainous habitats for mating, but otherwise can be found in a wide variety of habitats: deserts, savannas, grasslands, scrub forests, thick forests and open terrain. They have been seen at altitudes ranging from 10 and 2,000 meters (32.81 and 6562 feet). Habitat flexibility is important for a species that must travel such vast distances for food. Cinereous vultures select a roost tree to roost in near their nest tree during the breeding season to guard and defend their nest site. How the birds choose a roost tree is still debated but they tend to roost in older trees.

RELATED ARTICLES:

NORTHERN BIRDS factsanddetails.com

GREAT OWLS OF THE NORTH factsanddetails.com

WHITE-TAILED EAGLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

PTARMIGANS: COLOR CHANGES, DIRT AND THE SLOW MALE TRANSITION factsanddetails.com

Cinereous Vulture Characteristics and Diet

Cinereous vultures range in weight from 6.8 to 14 kilograms (15 to 31 pounds), with their average weight being 8.17 kilograms (18 pounds). They range in length from 1.1 to 1.2 centimeters (3.7 to 4 feet). Their wingspan ranges from 2.44 to 2.91 meters (8.01 to 9.55 feet). By some reckoning cinereous vultures are second largest birds of prey after Andean condors. The largest flying birds are albatrosses. Some data suggests cinereous vultures may actually be bigger than Andean condors but the data and the conclusion do not have wide support. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females are heavier and slightly larger than males. [Source: Katharine Barbeiro, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Cinereous vultures have a broad head and bodies covered in black and/or brown feathers. Their beak is black and their eyes are brown. Feathers on their head are smaller than those found on the rest of their body. Their legs are a grayish-blue or a whitish-yellow in adults, but during adolescence, their legs and beaks are pink.

Cinereous vultures are scavengers and carnivoress. Their main food sources are dead rabbits, sheep, and ungulates. They also feed on the carcasses of red deer, wild boars, pigs, and cattle. They rarely eat live animals, but snakes and insects have been killed and eaten by these vultures. Their powerful beaks have evolved to allow them to tear even the toughest flesh, muscle, and tendons into edible pieces.

Vultures find food using a combination of keen eyesight and a powerful sense of smell, depending on the species. Some are known for their exceptional sense of smell, allowing them to detect decaying flesh from a great distance, even hidden under foliage. Other vultures primarily rely on visual cues, such as spotting other vultures circling or landing around a carcass.

Cinereous Vulture Behavior

Cinereous vultures fly and are arboreal (live in trees), diurnal (active during the daytime), crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary) and solitary. They have been observed flying up to 75 kilometers to find food. Once they are done eating, they fly back to their nest. Their home range is anywhere they can fly in order to get food; however, no matter how far they fly, they always return to their nest. [Source: Katharine Barbeiro, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Cinereous vultures do not migrate. They fly great distances to get food but they always return to their nest to sleep. They stay in their nest throughout the year. They prefers to roost near their nest tree in the breeding season to guard and defend their nest site. Cinereous vultures may roost and soar together. At a carcass, they vultures are the dominant vulture species, but they are known to tolerate other vulture species and any other species that wants to eat. These vultures form colonies. That way if one finds food it can alert the others so all can feed.

Cinereous vultures communicate with sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. Like many other vulture species, they are very quiet. It is rare to hear vultures, but they may make croaks, grunts, and hisses when feeding at carcasses and have a querulous mewing, loud squalling, or roaring during breeding season. Their most useful sense that cinereous vultures have is their sight, which is used to find food.

Cinereous Vulture Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Cinereous vultures are monogamous, mate for life and engage in seasonal breeding. They mate once a year — from October through November. The number of eggs laid each season ranges from zero to two. The time to hatching ranges from 50 to 55 days. Parental care is provided by both females and males. Fledging age ranges from 95 to 120 days and the age in which they become independent ranges from 180 to 215 days. Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at four to five years. [Source: Katharine Barbeiro, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Incubation is from January through April and chick-rearing continues through August. Generally, only one egg is fertilized each season. Although extremely rare, two eggs have been observed. Young are fed by both parents for about 160 days; however, even after the young have fledged, they still return to the nest for food for several months.

Cinereous vultures construct huge that are 2.4 meters (8 feet) wide and 2.1 meters (7 feet) deep and composed almost entirely of sticks, pine needles, branches, and trash. An egg is deposited in February and incubated by both parents until April. After fledging the fledling leaves the nest but return to the nest for food from its parents and to sleep. This usually lasts two to three months.

Cinereous Vultures, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List,cinereous vultures are listed as Near Threatened. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. [Source: Katharine Barbeiro, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Cinereous vultures are rare in Europe and is included in Annex I of the European Union Bird Directive. In some places population of these birds has declined through accidental poisoning: when they vultures consume poisoned carcasses used to bait and reduce the populations of wolves, foxes, and jackals. Shooting these birds is illegal in many places, but it still occurs. Humans also affect vulture populations by eliminating their habitats with logging. In some places, man-made vulture-friendly habitats and feeding sites have been set up. Such habitats are mainly composed of oak and beech woods with many other trees and have housing and protective structures for the birds.

As of 2013, the global population of cinereous vultures was about 7,200 to 10,000 pairs. Their Spanish population included about 1,845 pairs, which is almost 95 percent of the European population and has spread to Portugal. Greece is their only other significant breeding ground in Europe. There are significant populations Turkey, where new breeding areas were discovered in Turkey in 1995, Azerbaijan and Iran and presumably Russia and Ukraine. Reintroduction programs are underway in Italy, France and elsewhere.

The presence of cinereous vultures is important for other species and keeping diseases in check.. Cinereous vultures are often among the first to show up at carcasses, usually eating the flesh before other smaller scavengers. Cinereous vultures tear through the carcass skin and make it easier for smaller scavengers to get good. The decaying carcasses often contain f=harmful bacteria and other parasites that can be passed to the smaller opportunistic scavengers, potentially increasing the incidence of disease in the ecosystem. Cinereous vultures, on the other hand, are adapted to digesting these harmful organisms without damage to themselves.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025