MALAYSIA IN THE EARLY CENTURIES A.D.

Various goods and Islam were likely brought to Southeast Asia by Muslim traders, who used dhows, boats like the one pictured here

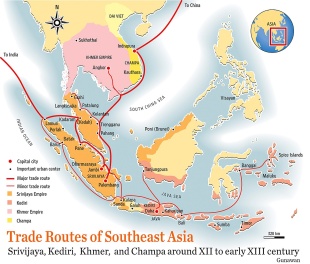

Little is known about Malaysia’s early history, but historians believe that as early as the first few centuries A.D. trade on the Strait of Malacca helped to create economic and cultural links among China, India, and the Middle East. Among the most powerful and enduring early kingdoms was Srivijaya, which ruled much of Peninsular Malaysia from the seventh to the fourteenth century with support from China and the Orang Laut (“men of the sea”) who originated from Peninsular Malaysia and were perhaps the region’s best sailors and fighters.

The Roman-era Greek geographer Ptolemy (A.D. 90 – 168) wrote about Golden Chersonese, which indicates trade with India and China has existed since the A.D. 1st century. On medieval versions of Ptolemy's map, originally made in the AD 2nd century, as the Golden Khersonese coincides with the Malay Peninsula. [Source: Wikipedia]

Situated along the maritime trade route linking China and southern India, the Malay Peninsula became deeply integrated into this commercial system. The Bujang Valley, strategically located at the northwestern entrance to the Strait of Malacca and facing the Bay of Bengal, was frequently visited by Chinese and South Indian traders. Archaeological discoveries—including trade ceramics, sculptures, inscriptions, and religious monuments dating from the A.D. 5th to the 14th centuries —attest to its long-standing role as a trading and cultural center. Over time, the Bujang Valley came under the administration of successive maritime powers, including Funan, Srivijaya, and Majapahit, until the eventual decline of regional trade.

Iron from the Kedah region was exported to ancient India, China, the Middle East, Korea, and Japan (See Old Kedah Below).

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA: HOMINIDS, FIRST PEOPLE, PROTO-MALAYS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE OF THE PACIFIC, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES: ORIGIN, HISTORY, EXPANSION factsanddetails.com

MALACCA SULTANATE: ORIGIN, HISTORY, PARAMESVARA factsanddetails.com

ARRIVAL OF EUROPEANS IN MALAYSIA: PORTUGUESE, DUTCH, CONQUESTS, FIGHTING factsanddetails.com

BRITISH IN MALAYSIA: TIN, RUBBER AND HOW THEY TOOK CONTROL factsanddetails.com

MALAYSIA HISTORY: NAMES, TIMELINE, HIGHLIGHTS factsanddetails.com

Early Malay Kingdoms

The earliest Hindu-Buddhist Malay kingdoms emerged from Indian cultural influence via trade routes around the second or third century A.D. Significant early centers on the Malay Peninsula include Langkasuka (in the Pattani region) and Kedah (Kadaram). The Bujang Valley in Kedah shows extensive archaeological evidence of early Indianized polities, including iron smelting as early as 110 A.D. This set the stage for later powers, such as Srivijaya and Majapahit.

By the first century AD, Southeast Asia had developed a network of coastal city-states centered on the Khmer kingdom of Funan, located in what is now southern Vietnam. This network extended across the southern Indochinese Peninsula and into the western Indonesian archipelago. From an early period, these coastal polities maintained sustained trade and tributary relations with China, while also remaining in close contact with Indian merchants.

Rulers in western Indonesia adopted Indian cultural and political models, evidence of which appears in Indonesian art and inscriptions from as early as the fifth century. Notable examples include an Amaravati-style Buddha statue discovered in southern Sulawesi and a Sanskrit inscription found east of present-day Jakarta. Additional inscriptions from Palembang in South Sumatra and from Bangka Island—written in Old Malay using a script derived from the Pallava alphabet—demonstrate that Malay rulers had adopted Indian administrative and religious models while preserving their indigenous language and social structures. These inscriptions mention a Dapunta Hyang, or lord of Srivijaya, who led military expeditions against rivals and invoked curses upon those who refused to obey his authority.

See Separate Article: KEDAH AND PERIS STATES: BUYANG VALLEY, ANCIENT ARCHAEOLOGY, CAVES AND FORESTS factsanddetails.com

Early Malaysian Trade

Sandwiched between the island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, the Strait of Malacca has long been the main artery of trade linking China, Japan, India, Arabia, and East Africa. In the Middle Ages, the strait was as central to global commerce as it is today. Harnessing the seasonal monsoons, ships from as far away as Canton sailed to Malacca between January and May. From July onward, the reversal of the winds carried them back toward India and Sri Lanka. Similar monsoon patterns in the Arabian Sea enabled vessels from Aden and East Africa to trade with Gujarat and India’s Malabar Coast. The interior of the Malay Peninsula was richly endowed with natural resources. Dense forests, coconut groves, fertile soil, abundant rainfall, and a population known for perseverance, industry, and hospitality made the region both prosperous and attractive. For centuries, ships docked along its coasts to conduct business. [Source: Lonely Planet, Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD wrote in the Encyclopedia of Islamic History, Wikipedia]

By the 2nd century A.D., Europeans were familiar with Malaya, and Indian traders regularly visited in search of gold, tin, and jungle woods. Within the next century, the Funan Empire, centered in present-day Cambodia, ruled Malaya. More significant, however, was the domination of the Sumatra-based Srivijayan Empire between the 7th and 13th centuries. A visitor around the year 1400 would have encountered Chinese, Indians, Omanis, Yemenis, Persians, and Africans mingling with traders from Sumatra, Java, Bali, and Canton, exchanging goods and forging commercial ties. China exported silk, brocades, porcelain, and perfumes; India supplied hardwoods, carvings, precious stones, cotton, sugar, livestock, and weapons. From the Malayan interior came tin, camphor, ebony, and gold. Sumatra contributed rice, gold, black pepper, and mace, while Java provided dyes, spices, and perfumes. Cloves arrived from the Maluku Islands, sandalwood from Timor, and Chinese ceramics ranked among the most prized commodities.

Muslim merchants dominated international trade across the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the East China Sea. A shared faith, strong commercial ethics, and widely accepted transaction laws based on sharia enabled them to build a vast trading network linking East Africa, southern Arabia, the Persian Gulf, and the Malabar Coast with Indonesia and southern China. As early as the eighth century, a Muslim trading post existed in Canton. Along the Malayan coast, a cosmopolitan society emerged in which merchants from Malabar, Arabia, and Africa lived alongside indigenous Malays and Chinese officials.

Early Malay sultanates functioned as “harbor principalities,” growing wealthy by controlling the trade of specific commodities or serving as vital way stations along major trade routes. Known to ancient Tamils as Suvarnadvipa, the “Golden Peninsula,” the region appeared on Ptolemy’s map as the “Golden Khersonese,” with the Strait of Malacca labeled Sinus Sabaricus. Trade links with China and India were established as early as the first century BC. During the early centuries of the first millennium, the peoples of the Malay Peninsula adopted Hinduism and Buddhism, religions that profoundly shaped local language and culture. Sanskrit writing was in use by at least the fourth century.

Malaysia and Funan, the Khmers and Chams

According to Khmer history, the earliest known civilisation was the 1st century Indianised-Khmer culture of Funan, in the Mekong Delta. The Khmer empire of Angkor was the last before the kingdom fled to various places seeking refuge. Palembang and later Malacca were among the places. Archeological evidences found that inhabitants of early Cambodia were peoples of Neolithic culture. They possessed good technical skills while the more advanced groups, who lived near the coast and in the lower delta of Mekong, cultivated irrigated rice. It is believed that they were the ancestors of the people living in insular Southeast Asia and islands of Pacific Ocean. They were also knowledgeable in iron and bronze works as well as possessing good navigational skills. (Source: Based on information from John F. Cady, Southeast Asia: Its Historical Development, New York, 1964.)

The similarity of the Cambodian Cham language and the Malay language can be found in names of places such as Kampong Cham, Kambujadesa, Kampong Chhnang, etc. and Sejarah Melayu clearly mentioned a Cham community in Parameswara's Malacca around 15th century. Cham is related to the Malayo-Polynesian languages of Malaysia, Indonesia, Madagascar and the Philippines. In mid 15th century, when Cham was heavily defeated by the Vietnamese, some 120,000 were killed and in the 17th century the Champa king converted to Islam.

In 18th century the last Champa Muslim king Pô Chien gathered his people and migrated south to Cambodia while those along the coastline migrated to the nearest peninsula state Terengganu, approximately 500 kilometers or less by boat, and Kelantan. Malaysian constitution recognises the Cham rights to Malaysian citizenship and their Bumiputera status. Now that the history is interlinked, there is a possibility that Parameswara's family were Cham refugees who fled to Palembang before he fled to Tumasik and finally to Malacca. Interestingly, one of the last Kings of Angkor of the Khmer Empire had the name Paramesvarapada.

Early Malaysian Kingdoms

In the A.D. first millennium Malay's became the dominant race on the peninsula. The small early states that were established were greatly influenced by Indian culture. Indian influence in the region dates back to at least the 3rd century B.C. After the A.D. 3rd century, Buddhism took hold in Sumatra and Java and to a lesser extent Malaysia and Borneo and remained strong until the massive conversion to Islam in the 15th century.

In the first millennium Chinese chronicles mention several coastal cities or city-states, however they don't give exact geographical location, so the identification of these cities with the later historical cities is difficult. The most important of these states were Langkasuka, usually considered a precursor of the Pattani kingdom; Tambralinga, probably the precursor of the Nakhon Si Thammarat kingdom, or P'an-p'an in Phunphin district Surat Thani, probably located at the Bandon Bay Tapi River. The cities were highly influenced by Indian culture, and have adopted Brahman or Buddhist religion.

There were numerous Malay kingdoms in the 2nd and 3rd century, as many as 30, mainly based on the Eastern side of the Malay peninsula. Among the earliest kingdoms known to have been based in what is now Malaysia is the ancient empire of Langkasuka, located in the northern Malay Peninsula and based somewhere in Kedah. It was closely tied to Funan in Cambodia, which also ruled part of northern Malaysia until the 6th century. According to the Sejarah Melayu ("Malay Annals"), the Khmer prince Raja Ganji Sarjuna founded the kingdom of Gangga Negara (modern-day Beruas, Perak) in the 700s. Chinese chronicles of the A.D. 5th century speak of a great port in the south called Guantoli, which is thought to have been in the Straits of Malacca. In the 7th century, a new port called Shilifoshi is mentioned, and this is believed to be a Chinese rendering of Srivijaya. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to Kedah Annals, Kadaram (Kedah Kingdom 630-1136) was founded by Maharaja Derbar Raja of Gemeron, Persia around 630 CE, and also alleged that the bloodline of Kedah royalties coming from Alexander The Great. The other Malay literature, Sejarah Melayu too alleged that they were the descendants of Alexander The Great. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article:FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Old Kedah

In Kedah, there are archaeological remains reflecting both Buddhist and Hindu influences that date to the A.D. early centuries.The area's history is inextricably linked to its iron industry. Archaeological findings have unearthed various historical mines, warehouses, factories, and a harbor, as well as a plethora of high-quality ores, furnaces, slag, and ingots. The Tuyere iron-smelting technique used in Sungai Batu is also recognized as the oldest of its kind. This technique produced highly sought-after goods that were exported to various parts of the Old World, including ancient India, China, the Middle East, Korea, and Japan. Based on early Sanskrit reports, the area was known as "the iron bowl." [Source: Wikipedia]

Gangga Negara was a semi-legendary Hindu kingdom mentioned in the Malay Annals, believed to have been located in what are now Beruas, Dinding, and Manjung in the state of Perak, Malaysia. One of its rulers is recorded as Raja Gangga Shah Johan. According to the legendary Hikayat Merong Mahawangsa, the kingdom was founded by Raja Ganji Sarjuna of Kedah, the son of Merong Mahawangsa, who was reputedly a descendant of Alexander the Great. Other traditions attribute the kingdom’s origins to Khmer royalty, placing its establishment no later than the A.D. second century.

The Bujang Valley was considered part of Old Kedah. Among the most significant finds is a rectangular stone slab inscribed with the ye-dharma hetu formula in Pallava script, dating to the seventh century. This inscription confirms the Buddhist character of a nearby shrine, of which only the base now survives. The text appears on three faces of the stone and may date as early as the sixth century. With the exception of the Cherok To’kun inscription, which was carved onto a large boulder, most inscriptions found in the Bujang Valley are relatively small and were likely brought to the region by Buddhist pilgrims or itinerant traders.

Over time, rulers in the western part of the archipelago adopted Indian cultural and political models. Three inscriptions discovered in Palembang (South Sumatra) and on Bangka Island—written in Old Malay using scripts derived from the Pallava alphabet—demonstrate the adoption of Indian administrative and religious influences while preserving indigenous language and social structures. These inscriptions attest to the existence of a Dapunta Hyang (lord) of Srivijaya, who led military expeditions against rivals and pronounced curses upon those who failed to obey his authority.

See Separate Article: KEDAH AND PERIS STATES: BUYANG VALLEY, ANCIENT ARCHAEOLOGY, CAVES AND FORESTS factsanddetails.com

Bujang Valley

The Bujang Valley (Malay: Lembah Bujang) is an extensive archaeological complex covering approximately 224 square kilometers (86 square miles). It is considered part of the Old Kedah kingdom, Recent discoveries at the Sungai Batu iron-smelting sites have greatly expanded the known extent of the settlement, increasing its estimated area to nearly 1,000 square kilometers (390 square miles). The site contains ruins dating back more than 1,500 years. Archaeologists have uncovered over 50 ancient temple structures, known locally as candi. The most impressive and best-preserved of these stands at Pengkalan Bujang in Merbok. The Bujang Valley Archaeological Museum, situated at Sungai Batu, houses many of the area’s key finds. Excavations there have revealed the remains of jetties, iron-smelting facilities, and a clay brick monument dated to around A.D. 110, identified as the oldest known man-made structure in Southeast Asia. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Bujang Valley, strategically positioned at the northwestern entrance to the Strait of Malacca and facing the Bay of Bengal, was frequently visited by Chinese and South Indian traders. This role is supported by archaeological discoveries—including trade ceramics, sculptures, inscriptions, and religious monuments—dating from the fifth to the fourteenth centuries. Evidence from the Bujang Valley suggests that local rulers adopted Hindu-Buddhist Indian cultural and political models earlier than contemporaneous polities such as Kutai in eastern Borneo, southern Sulawesi, or Tarumanegara in western Java, where Indian-influenced remains date to the early fifth century. Artifacts recovered from the valley—now displayed in the archaeological museum—include inscribed stone caskets and tablets, metal tools and ornaments, ceramics, pottery, and Hindu religious icons.

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Malaysia’s Bujang Valley is one of the earliest archaeologically documented crossroads for trade goods and religious ideas in Southeast Asia. The valley, which is located south of Mount Jerai in Kedah State near the coast of the Strait of Malacca, has been the subject of scholarly interest since the early nineteenth century. At that time, colonial officials with the East India Company uncovered evidence of a civilization bearing the influence of the Indian subcontinent, including traces of religious buildings and objects with motifs associated with Hinduism and Buddhism. Multiple excavations have since unearthed dozens of archaeological sites that suggest the region was home to a port and trade center where merchants from around Southeast Asia and beyond, including what is now the Arabian Peninsula, India, the Malay Archipelago, and China engaged in commerce and cultural exchange. Archaeologist John Miksic of the National University of Singapore says that, beginning in the seventh century A.D., the region may have become part of Srivijaya, a powerful empire based on the island of Sumatra to the south that wielded extensive influence over thousands of miles of coastline straddling the Strait of Malacca. “Most people assume that Srivijaya became the Bujang Valley’s overlord,” says Miksic. “But some others think Bujang entered into a trading alliance with them, something akin to the Hanseatic League of ports in the medieval period.” The Bujang Valley, Miksic says, was probably a Buddhist kingdom until around 1025, when the Hindu Chola Empire of south India conquered the region, as well as other ports on the Strait of Malacca. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

In 2024, Archaeology magazine reported: A life-size statue of a meditative Buddha was discovered at the site of Bukit Choras in the Bujang Valley. The stucco figure, which features the Buddha’s typical posture, garments, and facial expression, was found in the country’s largest known Buddhist temple, which was itself only discovered last year. Both the temple and the statue date to the 7th or 8th century a.d., when the area was at the heart of the Kedah Kingdom. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2024]

See Separate Article: KEDAH AND PERIS STATES: BUYANG VALLEY, ANCIENT ARCHAEOLOGY, CAVES AND FORESTS factsanddetails.com

Shrivijaya Kingdom

In the 7th century the powerful Shrivijaya kingdom in Sumatra spread to Malay peninsula and introduced a mixture of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. Shrivijaya was a maritime empire based in Sumatra that lasted for 500 years from the 8th century to the 13th century. It ruled a string of principalities in what is today Southern Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. When Srivijaya in Chaiya extended its sphere of influence, those cities became tributary states of Srivijaya.

The site of Srivijaya's centre is thought be at a river mouth in eastern Sumatra, based near what is now Palembang. For over six centuries the Maharajahs of Srivijaya ruled a maritime empire that became the main power in the archipelago. The empire was based around trade, with local kings (dhatus or community leaders) swearing allegiance to the central lord for mutual profit. [Source: Wikipedia]

From the 12th century onward, Srivijaya declined as its authority over vassal states fractured, conflicts with Javanese and Indian powers intensified, and its political center shifted to Melayu in Sumatra. The spread of Islam further weakened Srivijaya, while external powers—including the Siamese kingdom of Sukhothai and the Javanese Majapahit Empire—came to dominate much of the Malay Peninsula by the 13th and 14th centuries. By then, Srivijaya had lost Chinese support and control of key trade routes. In contrast, Borneo developed largely independently, with Brunei emerging as its principal power until British colonization in the 19th century.

Shrivijaya Kingdom in Malaysia

Relations between Srivijaya and the Chola Empire were initially friendly under Raja Raja Chola I, but deteriorated during the reign of Rajendra Chola I, who launched major invasions of Srivijaya in the early 11th century. In 1025–1026, Gangga Negara and Kedah were attacked by Rajendra Chola I, bringing Kedah—known variously as Kedaram or Kataha—under Chola control from 1025.

These invasions weakened Srivijaya’s influence over Kedah, Pattani, and Ligor, despite later Chola rulers having to suppress local rebellions. Kedah’s importance is reflected in early Indian literary sources, including Tamil, Sanskrit, and Buddhist texts. After the Chola period, the Buddhist kingdom of Ligor briefly controlled Kedah and used it as a base for campaigns against Sri Lanka in the 11th century. Subsequent Chola rulers, notably Virarajendra Chola, continued campaigns in Kedah to suppress rebellions and rival powers. These invasions weakened Srivijaya’s regional dominance, and by the late 11th century, Chola overlordship was established over Kedah under Kulothunga Chola I. [Source: Wikipedia]

The impact of the Chola expeditions left a lasting imprint on Malay historical memory. Chola rulers appear in Malay chronicles as “Raja Chulan,” and the legacy persists in Malaysia through royal titles and names derived from Chola traditions. Earlier Tamil sources, such as the 2nd-century poem Pattinapalai, already noted Kedah’s importance in Chola trade networks. After the Chola period, Kedah briefly came under the control of the Buddhist kingdom of Ligor, whose ruler Chandrabhanu used it as a base for military campaigns against Sri Lanka in the 11th century.

See Separate Article: SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

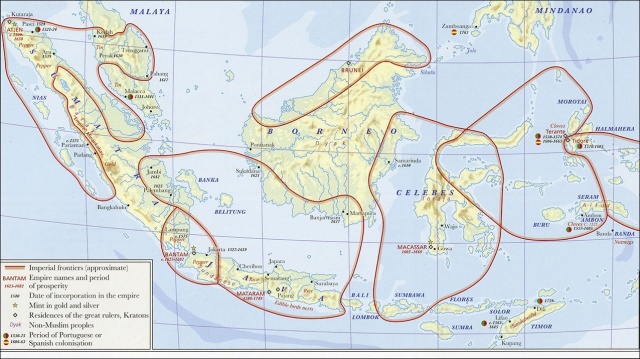

Majapahit Empire

In the 13th century the Malay peninsula was under the control of the Java-based Hindu Majapahit empire. The Majapahit Kingdom (1293-1520) was perhaps the greatest of the early Indonesian kingdoms. It was founded in 1294 in East Java by Wijaya, who defeated the invading Mongols.

Under the ruler Hayam Wuruk (1350-89) and the military leader Gajah Mada, it expanded across Java and gained control over much of present-day Indonesia—large parts of Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Borneo, Lombok, Malaku, Sumbawa, Timor and other scattered islands—as well as the Malay peninsula through military might. Places of commericial value such as ports were targeted and the wealth gained from trade enriched the empire. The name Majapahit stems from the two words maja, meaning a type of fruit, and pahit, which is the Indonesian word for 'bitter'.

An Indianized kingdom, Majapahit was the last of the major Hindu empires of the Malay archipelago and is considered one of the greatest states in Indonesian history. Its influence extended over much of modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia though the extent of its influence is the subject of debate. Based in eastern Java from 1293 to around 1500, its greatest ruler was Hayam Wuruk, whose reign from 1350 to 1389 marked the empire's peak when it dominated kingdoms in Maritime Southeast Asia (present day Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines). [Source: Wikipedia]

The Majapahit Kingdom Empire was centered at Trowulan near the present-day city Surubaya in East Java. Some look upon Majapahit period as a Golden Age of Indonesian history. Local wealth came from extensive wet rice cultivation and international wealth came from the spice trade. Trading relations were established with Cambodia, Siam, Burma and Vietnam. The The Majapahits had a somewhat stormy relationship with China which was under Mongol rule.

Hinduism fused with Buddhism were the primary religions. Islam was tolerated and there is evidence that Muslims worked within the court. Javanese kings rules in accordance with wahyu, the belief that some people had a divine mandate to rule. People believed if a king misruled the people had to go down with him. After Hayam Wuruk’s death the Majapahit Kingdom began to decline. It collapsed in 1478 when Trowulan was sacked by Denmark and the Majapahit rulers fled to Bali, opening the way to Muslim conquest of Java.

Majapahit flourished at the end of what is known as Indonesia's "classical age". This was a period in which the religions of Hinduism and Buddhism were predominant cultural influences. Beginning with the first appearance of Indianised kingdoms in the Malay Archipelago in the A.D. 5th century, this classical age was to last for more than a millennium, until the final collapse of Majapahit in the late 15th century and the establishing of Java's first Islamic sultanate at Demak. [Source: ancientworlds.net]

See Separate Article: MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

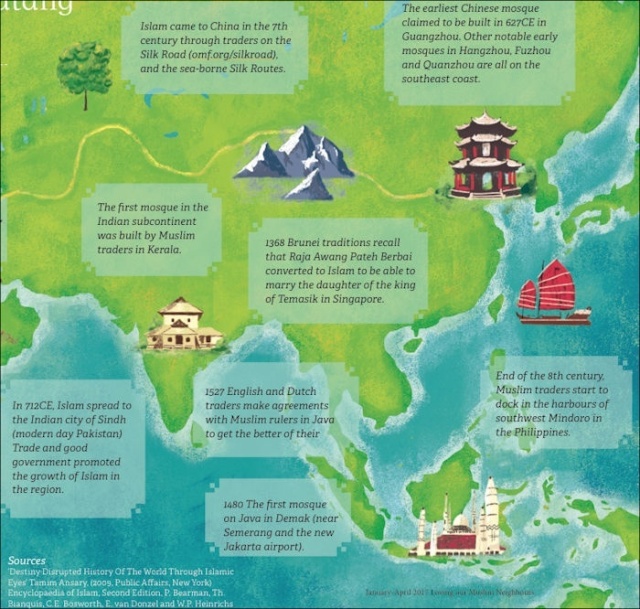

Islam Comes to Malaysia

Islam came to the Malay Archipelago via Arab, Persian and Indian traders, who controlled trade on the Strait of Malacca, in the 13th century, ending the age of Hinduism and Buddhism. It arrived in the region gradually, and became the religion of the elite before it spread to the commoners. The Islam in Malaysia was influenced by previous religions and was originally not orthodox. For the most part the process was peaceful; The people who brought Islam were traders first and missionaries second. Most were Sunnis. Shiites came later.

Hinduism and Buddhism were well rooted in Southeast Asia at the time Islam arrived. Around 1390, a Javanese prince named Parameswara was forced to flee his homeland. He landed on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula with a loyal following of about a thousand men and survived for nearly a decade through piracy and control of local trade routes. At the time, Siam (modern Thailand) was the dominant regional power. By about 1403, Parameswara expelled Siamese forces from the area and established the settlement of Malacca. The name Malacca is often linked to the Arabic word malakut, meaning marketplace, reflecting the presence of Arab traders who had maintained commercial links in the region since as early as the eighth century. [Source: Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD wrote in the Encyclopedia of Islamic History]

Once established, Parameswara promoted peaceful trade, and Malacca rapidly grew into a prosperous international port. Muslim merchants dominated Indian Ocean commerce, with Arabic serving as the lingua franca of trade, while Islam was spreading across the Indonesian archipelago. Across the Strait of Malacca, the powerful Muslim kingdom of Pasai and the rising state of Aceh exerted growing influence. According to local tradition, around 1405 Parameswara embraced Islam, married a princess from Pasai, and adopted the name Sultan Iskander Shah—a story often portrayed in folklore as symbolizing the introduction of Islam to Malaya.

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

Malacca Sultanate

The commencement of the current Malay nation is often traced to the fifteenth-century establishment of Malacca (Malacca) on the peninsula’s west coast. Malacca’s founding is credited to the Srivijayan prince Sri Paramesvara, who fled his kingdom to avoid domination by rulers of the Majapahit kingdom.

Early Malaysian cities and states originated in the coast and then moved to interior. These traded expensively with Chinese traders, who began arrived in numbers in the 14th century. Groups such as the Acehese, the Bugis and the Mnangkabau fought for dominance over the peninsula.

Before colonization, Malaysia was ruled sultanas who ruled over fiefdoms. The largest and most powerful of these Malacca kingdom on the Malay peninsular that was dominant power 1400-1511. It vied with the Chinese and Thais for control of the region.

Malacca was founded in 1402 by Paramesvara, a prince who fled from Sumatra and established a port which attracted trading ships from as far away as China, India and the islands near New Guinea. These ships carried sandalwood, pearls, porcelain, silk, gold, tin , bird-of-paradise feathers and spices such as cloves, mace and nutmeg from the Spice Islands in what is now eastern Indonesia.

See Separate Article: MALACCA: HISTORY, SULTANATES, COLONIALISM factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated January 2026