RURAL LIFE IN CHINA

There is a wide gap between the wealth of the impoverished countryside and the booming cities, with the income of rural residents less than a third of that of urban residents. But some economists have said China’s measure is actually much higher, when illicit and poorly reported sources of wealth and the lack of good health care, education and other services in rural areas are taken into account. The annual per capita disposable income of or rural residents was 2,762 yuan (around $300) in 2006 compared to 8,799 yuan for urban dwellers. At that time For every 100 household in the countryside there were 89 color televisions, 22 refrigerators and 62 cell phones. By contrast, for every 100 households in the cities there were 137 color televisions, 92 refrigerators and 153 cell phones.

There is a wide gap between the wealth of the impoverished countryside and the booming cities, with the income of rural residents less than a third of that of urban residents. But some economists have said China’s measure is actually much higher, when illicit and poorly reported sources of wealth and the lack of good health care, education and other services in rural areas are taken into account. The annual per capita disposable income of or rural residents was 2,762 yuan (around $300) in 2006 compared to 8,799 yuan for urban dwellers. At that time For every 100 household in the countryside there were 89 color televisions, 22 refrigerators and 62 cell phones. By contrast, for every 100 households in the cities there were 137 color televisions, 92 refrigerators and 153 cell phones.

A typical village farmer grow rice, corn, chilies and vegetables on a half acre of land, and maybe keeps some chickens and pigs. Farmers produce enough to eat but not much to sell. There are often inadequate basic public services such as education, health and applications of new technologies. Typical rural families live in simple wooden houses, use outhouses and cook in shacks over open hearths. By the early 2000s many villagers had televisions and even washing machines, refrigerators and DVD players, but many villages only had electricity during the night as rural industries needed the power during the day. Land-line phones were still rare. Cell phones and smartphones are now commonplace. In villages outside Shanghai you can find people with stylish haircuts and expensive suits that live in houses with coal grills and plastic tables.

Today many of China’s villages are hollowed out. Michael Standaert of the BBC wrote: ““Over the past few decades, many rural villages have either been ignored and isolated because of their geography, or depopulated by years of flight of the best and brightest to urban areas in the east for jobs and education. These “left behind” villages often became empty shells, mostly inhabited by the old or the very young, only springing to life when families returned during the annual lunar new year holiday.” A graduate of China's best university, Peking University, reported in the China Youth Dailyon his return to his native Luling, in Jiangxi Province, and was shocked by the changes that occurred during his short absence: the disappearance of age-old village traditions, the pursuit of money above all else, and the poor education of children. [Source: Michael Standaert, BBC News, September 6, 2020; China Youth Daily, February 19, 2016]

Some people in the countryside are staying put and resisting the trend to migrate to the cities. Singaporean job recruiter Brien Chua told the Strait Times in the late 2000s, “With lodging expensive and food costing more than double the price than back home, no one wants to move to the big cities anymore.” Some migrants go home and find a spouse and settle down.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE VILLAGES factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGES IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGE GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PEOPLE IN A 19th CENTURY CHINESE VILLAGE factsanddetails.com ; RURAL POOR IN CHINA AND PROBLEMS IN CHINESE VILLAGES factsanddetails.com ; RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND MODERNIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBANIZATION OF THE CHINESE COUNTRYSIDE factsanddetails.com ; POVERTY AND POOR PEOPLE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RURAL POOR IN CHINA AND PROBLEMS IN CHINESE VILLAGES factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; INCOME DISPARITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER THE COMMUNISTS Factsanddetails.com/China ; PROBLEMS FACED BY FARMERS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; LAND SEIZURES AND FARMERS IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; People’s Daily article peopledaily.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Rural Life “Will the Boat Sink the Water: The Life of China’s Peasants” by Chen Guidi and Wu Chuntao (Public Affairs, 2006) Amazon.com ; Peasant Life in China: A Field Study of Country Life in the Yangtze Valley by Hsiao-T'Ung Fei Amazon.com; “Gao Village: A Portrait of Rural Life in Modern China” (1999) by Mobo C. F. Gao Amazon.com; “Gao Village Revisited: The Life of Rural People in Contemporary China” (2018) by Mobo C. F. Gao Amazon.com; “The Educational Hopes and Ambitions of Left-Behind Children in Rural China” by Yang Hong Amazon.com; “Daoist Priests of the Li Family: Ritual Life in Village China” by Stephen Jones Amazon.com; “Communities of Complicity: Everyday Ethics in Rural China” by Hans Steinmüller Amazon.com; Chinese Village Life in the Old Days “Rural China: Imperial Control in the Nineteenth Century” by Kung-Chuan Hsiao | J Amazon.com; “Village Life in China” (early 1900s) by Arthur Henderson Smith Amazon.com; “The Man Awakened from Dreams: One Man’s Life in a North China Village, 1857-1942" by Henrietta Harrison Amazon.com; “Rural China on the Eve of Revolution: Sichuan Fieldnotes, 1949-1950 by G. William Skinner, Stevan Harrell, et al. Amazon.com; Village Life in the Mao Era “Cadres and Kin: Making a Socialist Village in West China, 1921-1991" by Gregory A. Ruf Amazon.com ; “Rightful Resistance in Rural China” (Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics) by Kevin J. O'Brien and Lianjiang Li Amazon.com; “Revolution, Resistance, and Reform in Village China (Yale Agrarian Studies Series) by Edward Friedman , Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, et al. Amazon.com; “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su Amazon.com; Changing Village Life “Village China Under Socialism and Reform: A Micro-History, 1948-2008" by Huaiyin Li Amazon.com; “China in One Village: The Story of One Town and the Changing World” by Liang Hong and Emily Goedde Amazon.com; “The End of the Village: Planning the Urbanization of Rural China” by Nick R. Smith Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com; “The Unknown Cultural Revolution: Life and Change in a Chinese Village” (2008) by Dongping Han Amazon.com

China in One Village

“China in One Village: The Story of One Town and the Changing World” by Liang Hong; translated by Emily Goedde (London: Verso, 2021) is based on the writer’s bestselling books in China. Combining family memoir, literary observation, and social commentary, the book is about the writer’s extended family in Henan province and how it was torn apart by the changes in Chinese society and how her village was hollowed-out by emigration, neglect, and environmental degradation.

“A professor of Chinese literature at at Renmin University in Beijing with a deep interest in sociology,Liang Hong wrote three books in Chinese about life in her home village in Henan Province: “China in Liangzhuang” (2010), “Going Out of Liangzhuang” (2013) and “History and My Moments” (2015), In her books about Chinese village life, Liang Hong describes regional snacks and specialties and traditional Lunar New Year customs as well as hardships that villagers face at home and in their quest for a better life. “Villagers are migrating in large numbers. They want to seek a ‘land flowing with milk and honey’ even if they might die half way there, a bit like what is described in Exodus, ” Liang wrote in “Going Out of Liangzhuang”. “But they fail to find ‘milk and honey.’ Rather, they struggle and drift on the margins and shadows of the land, being discriminated against, forgotten and dispersed and stuck in a dilemma… They are abandoned.” [Source: Xu Ming, Global Times, April 28, 2015]

Xu Ming wrote in the Global Times:“Through her father’s struggle with the then Party Secretary of the village towards the end of Cultural Revolution (1966-77), villagers’ love for Hong Kong TV series in the 1980s and the clash between commercialism and traditional villages after the nation’s reform and opening-up, Liang manages to build a relationship between ordinary people like herself and big events in history. But she immediately also depicts how powerless ordinary people can become amongst a wave of historical change.

““For a Chinese, sorrows and joys are never a natural part of life, but rather are forced changes due to changes in politics or systems,” Liang wrote. “That type of life and tradition fade quickly like the tide… Its speed and the wounds left behind are appalling… From Liangzhuang’s fate, I can see that we still have a long way to travel along the path of ‘modernization’ and, if we do not deal with the relationship between ‘villages, ’ ‘cities’ and ‘modernization’ right now, Liangzhuang and countless other Liangzhuangs will continue to drift without an anchor.” As China’s rapid urbanization makes the downfall of its rural areas seem inevitable, many people have started to pay more attention to the fate of rural villages. “This shows there is a crisis and people are generally anxious about this issue, ” Liang said, going on to explain that she is worried that rural issues may just become some emotional fad that never gets treated seriously in the long run.

Urban Versus Rural Populations in China

According to the 2020 census in China, The number of people living in urban areas — cities and towns — was 901.99 million, accounting for 63.89 percent of the total population, while 509.79 million people (36.11 percent) lived in rural areas. Compared to 2010, the urban population grew 236.42 million and the rural population decreased by 164.36 million. The proportion of urban population rose by 14.2 percent. [Source: Ryan Woo and Raju Gopalakrishnan, Reuters, May 11, 2021]

According to China’s 2020 census and the National Bureau of Statistics of China: The share of urban population went up by 14.21 percentage points. With the in-depth development of China’s new industrialization, informatization and agricultural modernization, and the implementation of the policy to help people who have relocated from rural to urban areas to gain permanent urban residency, China’s new urbanization has been advanced steadily and the urbanization construction has scored historical achievements over the past ten years. [Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, May 11, 2021]

According to the 2010 census, 51.3 percent of China’s population lives in rural areas. This is down from 63.9 percent in the 2000 census, which used a different counting system, and over 95 percent in the 1920s. There are around 800 million rural peasants and migrant workers — roughly 500 million farmers and 300 million to 400 million excess unskilled rural laborers. The rural population has declined from 82 percent in 1970 to 74 percent in 1990 to 64 percent in 2001 to 56 percent in 2007 and is expected to drop below 40 percent by 2030. Land essentially belongs to local government, a holdover from the commune era.

Average disposable annual income for Chinese urban residents in 2012 was the equivalent of about $4,000, an increase of 9.6 percent after taking inflation into account. Average rural net income was just under $1,300 per person, a rise of 10.7 percent after adjusting for inflation, the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics announced in January. [Source: Chris Buckley, New York Times, February 5, 2013 ^^]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, “All over China, planners are busy emptying the countryside of people, leveling villages, and replacing the small-plot agriculture that defined rural parts of the country for millennia with American-style industrial agriculture. Urban areas, meanwhile, have lost most of their distinctive characteristics. Even in cities known for their beauty, uniformity rules: in Hangzhou, the entire waterfront along the Grand Canal has been leveled except for one stone bridge. The rest is now apartment blocks and bars. Cities like Wuxi are even worse; the old city has been eradicated in favor of an industrial park aesthetic wedded to 1950s-style American automobile culture, with everything planned around highways, shopping malls, and subdivisions. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, June 6, 2013 ]

China's City Dwellers Surpass the Rural Population in 2011

In January 2012, the Chinese government said the number of people living in cities exceeded the rural population for the first time. Urban dwellers now represent 51.27 percent of China's entire population of nearly 1.35 billion — or 690.8 million people — the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said. It added that China had an extra 21 million people living in cities by the end of 2011 compared to a year earlier — more than the entire population of Sri Lanka — while the number of rural dwellers dropped. [Source: AFP, January 17, 2012]

In January 2012, the Chinese government said the number of people living in cities exceeded the rural population for the first time. Urban dwellers now represent 51.27 percent of China's entire population of nearly 1.35 billion — or 690.8 million people — the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said. It added that China had an extra 21 million people living in cities by the end of 2011 compared to a year earlier — more than the entire population of Sri Lanka — while the number of rural dwellers dropped. [Source: AFP, January 17, 2012]

AFP reported: “The shift marks a turning point for China, which for centuries has been a mainly agrarian nation, but which has witnessed a huge population shift to cities over the past three decades as people seek to benefit from the nation's economic growth. The development experts warned was likely to put strain on society and the environment. "Urbanisation is an irreversible process and in the next 20 years, China's urban population will reach 75 percent of the total population," Li Jianmin, head of the Institute of Population and Development Research at Nankai University, told AFP. "This will have a huge impact on China's environment, and on social and economic development."

A significant portion of China's urban dwellers are migrant workers — rural residents seeking work in towns and cities — who have helped fuel growth in the world's second-largest economy. A national census published in April last year showed China counted more than 221 million migrants, and a government report released months later predicted that more than 100 million farmers would move to cities by 2020.

Li said the rising number of urban dwellers would put a strain on resources as new or expanded cities would have to be built, adding that different urban centres had adopted different attitudes towards the issue. "Big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai have already clearly stated they want to contain the population increase," he said. They "have implemented a number of measures that are necessary as it is a severe test for local resources and traffic." But he said some small and medium-sized cities were still actively encouraging the rural population to become urbanites, which put a strain on resources and could pollute the local environment.

Rural Families in China

In contemporary society, rural families no longer own land or pass it down to the next generation. They may, however, own and transmit houses. Rural families pay medical expenses and school fees for their children. Under the people's commune system in force from 1958 to 1982, the income of a peasant family depended directly on the number of laborers it contributed to the collective fields. This, combined with concern over the level of support for the aged or disabled provided by the collective unit, encouraged peasants to have many sons. Under the agricultural reforms that began in the late 1970s, households took on an increased and more responsible economic role. The labor of family members is still the primary determinant of income. But rural economic growth and commercialization increasingly have rewarded managerial and technical skills and have made unskilled farm labor less desirable. As long as this economic trend continues in the countryside in the late 1980s, peasant families are likely to opt for fewer but better educated children. [Source: Library of Congress]

The consequence of the general changes in China's economy and the greater separation of families and economic enterprises has been a greater standardization of family forms since 1950. In 1987 most families approximated the middle peasant (a peasant owning some land) norm of the past. Such a family consisted of five or six people and was based on marriage between an adult son and an adult woman who moved into her husband's family. The variant family forms — either the very large and complex or those based on minor, nonstandard forms of marriage — were much less common. The state had outlawed concubinage, child betrothal, and the sale of infants or females, all of which were formerly practiced, though not common. Increased life expectancy meant that a greater proportion of infants survived to adulthood and that more adults lived into their sixties or seventies. More rural families were able to achieve the traditional goal of a three-generation family in the 1980s. There were fewer orphans and young or middle-aged widows or widowers. Far fewer men were forced to retain lifelong single status. Divorce, although possible, was rare, and families were stable, on-going units.

Views on Rural Life in China

In his book “The Villagers”, Richard Critchfield wrote: "I found that once you stepped inside a [Chinese] peasant family's household walls, property, marriage and the family mattered just as much as in any village. There were the same proudly displayed photographs, the same complaints about the expenses of weddings, the same deference shown to old people, even the same mind-numbing homemade country liquor that is, alas, the gesture of having broken the social ice from Africa to India." [Source: "The Villagers" by Richard Critchfield, Anchor Books]

A peasant farmer told the New York Times, "There's a huge difference between life now and the way it was. Our life today is better than a landlord's life in the past. But tell this to a young people and they don't want to hear. They say, Go away! They don't know about the old life...Last year [my son] wanted to buy a stereo cassette recorder for [$80]. I said, 'No that's too much. We should buy a mule.' A mule can work. It's useful. A stereo isn't. And a mule is so big, while a stereo is so small." [Source: Sheryl Wudunn, New York Times magazine, September 4, 1994]

One villager in Henan Province told the Los Angeles Times, “Farmers are realistic. If their kids are not high achievers at school, the parents just want them to finish school as soon as possible, get a job, build a house, and get married,”

Mao publically idealized peasants, he sent dwellers to the countryside to learn from them. Many think his actions were motivated purely by politics. The best education, health care and other benefits generally went to urban people, perpetuating inequality that exists today.

Wei Minghe was in his late 60s. He still had the rawboned build of a farmer, but now he lived in a retirement apartment in the nearby city of Huairou, although he returned faithfully each year for Qingming. Later that day, I gave him a ride back to the city. When I asked him if he missed Spring Valley, he said, "Before this apartment, I never lived in a place with good heat." His view of progress made perfect sense, just like the wishes of the ancestors — tile roofs versus thatched. [Source: Peter Hessler, National Geographic, January 2010]

Peter Hessler wrote: “In 2001, I began renting a home in a village, partly because I was curious about the region's history, but soon I realized that glimpses of the past were fleeting. Like most Chinese of the current generation, the villagers focused on today's opportunities: the rising prices for local crops, the construction boom that was bringing new jobs to Beijing, less than two hours away.

On the making of his documentary film “Beijing Besieged by Garbage”, photojournalist and filmmaker Wang Jiuliang said: In the summer of 2008, I returned to my hometown, a small rural village... I needed to find particularly clean natural environments to use as backgrounds for some photographs. But such places are hard to find now. Everywhere, covered by plastic tarps, there is the so-called modern agriculture, which has produced a countless number of discarded pesticide and chemical fertilizer packages scattered across the fields, ditches, and ponds. Herbicides and pesticides together have transformed the once-fertile natural environment into a lifeless one, and the rapidly developing consumerist lifestyle of the villagers has filled the village with piles of nondegradable garbage. The clean and beautiful hometown of my childhood memories — only a decade or two old — is nowhere to be found. [Source: Wang Jiuliang,, cross-currents.berkeley.edu, dgeneratefilms.com]

Life of a Fujian Peasant

Describing the early of a poor Chinese man who eventually made his way to New York, Kirk Semple and Jeffrey E. Singer wrote in the New York Times, “Mr. Wang grew up in Gui’an, a rural village in a mountainous region of Fujian Province; he dropped out of school when he was about 13 to join his relatives in the rice paddies.” “He told jokes, even on the hardest days,” his older sister, Wang Wenzhen, recalled in a telephone interview from the family’s home in Gui’an. “But he was also an introverted, reserved person; didn’t share his true feelings.” [Source: Kirk Semple and Jeffrey E. Singer, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

As a young man, Mr. Wang never talked about career plans, his sister told the New York Times “We are in a very backward village,” she explained. “All they can think about is making more money. What else can we dare to wish for?” She added: “I am sure he had his own dream, but he never talked about it. He knew that’s impossible.”

His father died of a stomach ailment when Mr. Wang was 19, tipping the family deeper into poverty. Mr. Wang left home in search of better work to help support the family and, through his 20s and 30s, chased opportunities for work in Fujian Province, mostly manual labor. For several years he drove a taxi, often taking the night shift so he could help with household chores during the day and take his mother, who was chronically ill, to the hospital, Ms. Wang said.

“Mr. Wang struggled not only with work but also with love. As his friends successfully found mates, married and started families, Mr. Wang, a thin man with close-set eyes and a crop of thick black hair, met failure. His sister blamed the family’s economic straits. “Nobody wanted to pick him,” she said. “Which girl would want to marry into poverty?”

“When he was about 30 — old to be a bachelor by the standards of his village — he married Lin Yaofang and they had a baby, a girl. When Ms. Lin became pregnant again, in violation of the country’s one-child policy, the authorities made her get an abortion, relatives and friends said.When word of her third pregnancy reached the government, he later told friends, officials went to their house to take Ms. Lin away, leading to Mr. Wang’s detention and beating.”

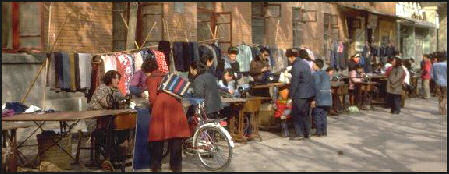

Sewing ladies

Life of a Hunan Peasant Who Wants to Get Out

Jiayang Fan wrote in The New Yorker:“Xia Canjun was born in 1979, the youngest of seven siblings, in Cenmang, a village of a hundred or so households nestled at the foot of the Wuling Mountains, in the far west of Hunan Province. Xia’s mother was illiterate, and his father barely finished first grade. The family made a living as corn farmers, and had been in Cenmang for more generations than anyone could remember. The region was poor, irrigation was inadequate — the family often went hungry — and there were few roads. Trips to the county seat, Xinhuang, ten miles away, were made twice a year, on a rickety three-wheeled cart, and until the age of ten Xia didn’t leave the village at all. But he was never particularly unhappy. “When you are a frog at the bottom of the well, the world is both big and small, ” he likes to say, referring to a famous fable by Zhuangzi, the Aesop of ancient China, in which a frog, certain that nowhere can be as good as the environment he knows, is astonished when a turtle tells him about the sea. As a child, Xia said, he was “a happy frog, ” content to play in the dirt roads between the mud houses of the village.[Source: Jiayang Fan, The New Yorker, July 23, 2018]

“In 1990, in sixth grade, Xia saw a map of the world for the first time. Of course, Cenmang wasn’t on it. Neither was Xinhuang, the city that loomed so large in his imagination. “The world was this great beyond, and we were this dot that I couldn’t even find on a map, ” he told me. The same year, the Xias bought their first TV, a black-and-white set so small that it could have fit inside the family wok. Market reforms were transforming China, but in Cenmang changes arrived slowly. It was several years before another appliance, a washing machine, entered the household.

“Still, rather than becoming a manual laborer, like his parents and siblings, Xia was able to go to technical college, and afterward he got a job at a local company that produced powdered milk. He married a girl from a nearby village and had a son. In 2009, he bought his first smartphone. Not many of his friends knew much about the Internet in those days, but Xia’s eyes were opened: “Everything that was going on in China could be squeezed onto that screen.” When the powdered-milk company downsized, he decided that it was time to look farther afield. He moved to Shenzhen, a sprawling coastal city, and found a job as a courier, becoming one of China’s quarter of a billion migrant workers.

“Life in the big city was at once overwhelming and colorless. Work consumed most of his days, and people were aloof, with none of the warmth he’d known back home. Whereas Xia had some connection to nearly everyone in Xinhuang and its surrounding villages, Shenzhen was an anonymous jumble, in which he felt like “a tiny, undifferentiated dot.” Then, eighteen months in, an unexpected opportunity arose. Xia had been making deliveries for JD.com, the second-biggest e-commerce company in China, and he heard that the business was expanding into rural Hunan. A regional station manager would be needed in Xinhuang.”

Farmer's Life in China in the 2010s

Farmer in a 1935 pre-Mao film Victor Mair, University of Pennsylvania, wrote in the MCLC List: A visiting graduate student from Zhejiang (Huzhou) told me about the life of his parents. Here are some of the facts he recited to me. 1) They own 1 MU of land. 1 mu = 0.16473692097811 acre. 2) On that land they grow paddy rice. 3) They also have a couple of mulberry trees and are trying to make some money (a tiny amount) by raising a small quantity of silkworms. 4) Apparently they can almost grow enough rice for their own needs, but they must seek work in factories to pay for their other needs. [Source: Victor Mair, University of Pennsylvania]

The husband (father) works in the local water treatment plant: 10 hours a day, 7 days a week. I don't know exactly what the wife (mother) does, but it is a similar kind of job. Neither the mother nor the father receive any benefits from their jobs except a very small salary (about 1,000 RMB [$156.519] per month, e.g., they have no medical insurance and have no retirement benefits. Their jobs away from home are characterized as "informal" — i.e., such jobs have no benefits or security. This is the sort of job that virtually all farmers who are lucky enough to find extra work away from home have. I asked the student what happens when his parents get sick. He said, "They can't afford to get sick." I said, "What if they really get sick?" The student said that, in such a case, people have to borrow money from family and friends to pay their medical expenses. But, I said, then they have to go in debt and it would be very stressful to try to pay back the people to whom they owe money when their income is so marginal in the first place. He said, "That's true, so they truly can't afford to get sick."

When they retire, the parents will receive 100 RMB ($15.6519) per month from the farmers' association; they will receive nothing from their other "informal" jobs. A pound of pork costs 25 RMB ($3.91298). If they get sick after they retire, they have to rely on their meager savings to pay for treatment. This means, even more than when they were working, that they really can't afford to get sick. And, if they do get sick, the treatment they receive will be of a very inferior kind (because they won't be able to pay for a good doctor and won't be able to make the bribes that are necessary for even the most minimally decent kind of medical treatment).

The student said that his parents consider themselves fortunate in comparison with most farmers in other parts of China. The southeast coastal area where the visiting graduate student is from is by far the richest area of China. He told me that's why there is a huge influx of migrants from poor areas like Gansu and Guizhou. People can barely survive in such areas, so they are forced to come to urban regions to work in factories for very low wages (such jobs are rarely available in the poor areas they come from).

Putting a Farmer's Life into Perspective

In response to Victor Mair's notes on "The Farmer's Life in China," Matt Sommer wrote: There’s another way to look at this situation, taking a longer-term view: Back in the Mao era, when there was relatively little rural industrialization and almost no opportunity to migrate in search of other work, these people almost certainly would not have had access to those factory jobs you mention. So they would have been stuck on the land, doing hyper-involuted agriculture round the clock, trying to squeeze every last bit of rice out of their little field, with very little to show for their back-breaking labor. They would have been hungry and malnourished all the time.

Also, the collectives they were trapped in would have provided as little or nearly as little safety net as they have now. The reform era has created a huge amount of rural industrialization, esp in the main coastal areas like Zhejiang, and that has had the benefit of soaking up a lot of the excess, under-employed labor that had previously had no outlet except for extremely labor-intensive, inefficient agriculture that was involuted far beyond the point of diminishing returns. The people you mention are now able to work all day in factories and do their agricultural work in their spare time — probably with very little decline in grain output per field. (This is typical for much of the Yangzi Delta.) That is testimony to how much under-employment had existed there prior to the availability of the factory jobs — all that labor could be taken out of agriculture without lowering grain production. The fact that the percentage of people working in agriculture overall is now down to about 50 percent is further testimony to that change — the percentage would have been closer to 70-75 percent a couple decades ago, but a lot of that labor was simply wasted b/c of incredible inefficiency of its use.

Another point worth considering is that this couple’s son is now a grad student at university — quite a fantastic opportunity for him as an individual, but also for their entire family. The fact is, if we were still in the Mao era, that young man you met would almost certainly be stuck on the farm with his parents, and they would be trying to feed three people from that rice paddy, w/o the factory jobs or the chance at higher education. Because of their son’s opportunities, the whole family’s standard of living is bound to improve, once he gets out of school. Obviously, that’s not typical; but it points to the larger phenomenon of younger people from the countryside being able to leave and look for other, better (or at least not as bad) situations elsewhere. There are lots of poor rural areas where nearly all the young people (especially the women) have left. That opportunity for labor to migrate — together with the rural industrialization — is the reason why the percentage of population (under-)employed in agriculture has been dropping so rapidly, and it’s one of the main reasons China’s GDP is rising so rapidly. Once the situation stabilizes (which eventually it will have to do), then China’s GDP growth rate is bound to slow down quite a bit. Already, labor costs in China are rising, which suggests that this may be starting to happen.

None of this is intended to prettify their situation or gloss over the terrible problems you point out. The benefits of industrialization and the reform era have not been equally shared — to say the least! But having said that, I — m convinced that the situation you describe is actually a net improvement over what it would have been twenty-five or thirty years ago. I bet the rural suicide rate was at least as bad (prob even worse) in the Mao era and in the early 20th century as it is now — Margery Wolf published an article back in the early 1970s about female suicide in early 20th century Taiwan (using the Japanese household registers, which are very accurate and precise), and the demographic profile she came up with was basically the same as what we see in rural China now: i.e. mostly women right around marriage age and elderly women.

Rural Daily Life in China

In rural areas, time as measured by a clock has little relevance. People wake up at dawn and go about their chores until they are finished or its gets dark. In hot climates, people wake up early, often between 4:00 and 5:00am, and do their most arduous tasks before it gets too hot. During the hottest hours people rest and nap and resume their activities in the relatively cooler hours before sunset. As a rule people usually go to bed pretty early.

One villager in Gansu told the Washington Post that on a typical day she rises at 6:00am. cleans the floor and furniture and cooks breakfast. Afterwards she weeds the wheat field and them returns to cook lunch and feed the chickens. After more fieldwork she returns to cook dinner. After dinner she and her children sit on hard bed and she tells them stories or they watch television.

Villages are often empty on the morning because everyone is out working in the fields or doing other chores. Before breakfast, a rural family usually feed their animals, and collects eggs and milk. Water is tossed outside during the dry season to help keep down the dust. Treks often have to be made a kilometer or so outside the village to fetch firewood for cooking or to make charcoal and sometimes to collect water for bathing and drinking. During the rainy season water is collected off the roof of the house.

Rural Chores in China

Life in the countryside in much of China has changed little in the last thousand years. Rice is still planted in paddies by hand and tilled by hoes or wooden plows pulled by oxen or water buffalo. Pigs and herds of ducks wander around the farms.

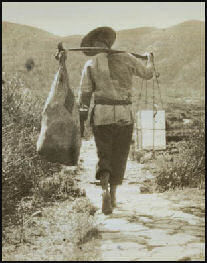

The roads are filled with slow moving tractors, peasants carrying belongings on shoulder poles, peasants carrying heavily-loaded baskets yokes and farmers moving everything from produce to cement in hand carts, bicycles or carts attached to their bicycles.

Newly harvested grain is threshed in the central square; water is collected from a hand pump; Dried red peppers , onions and garlic are hung from houses.. Hours are spent washing clothes in the afternoon in streams that feed fish ponds and rice fields. While the clothes are being washed, small gates into the pond and irrigation ditches are closed so the fish and crops are not contaminated by soapy water. Chores such as washing clothes are performed communally in some villages — a hold over from the collective farming days.

Villagers are very resourceful. Soccer balls are made from tin cans and large insects are tied to strings and kept as pets. Nothing is wasted in China. Human waste is collected from family outhouses and used as fertilizer called night soil. Outhouses are often placed near pig sties so waste can be collected from both sources and used for fertilizer. The morning distribution of night soil is common sight throughout China.

See Agriculture, Economics

Rural Income and Markets in China

A typical family of seven described by Business Week in 2000 lived in a four room house, used 0.64 of an acre for growing rice, used 0.59 an acre for growing other crops and owned four pigs, one horse and 20 ducks. Their expenditures were $546: $217 for food, $96 for transportation, $72 for fertilizer and pesticides, $48 for medicine, medical services, $36 for local taxes; $7 for road building and improvement; $4 for power station maintenance; $6 for education and culture and $60 for cloth and clothes.

A typical family of seven described by Business Week in 2000 lived in a four room house, used 0.64 of an acre for growing rice, used 0.59 an acre for growing other crops and owned four pigs, one horse and 20 ducks. Their expenditures were $546: $217 for food, $96 for transportation, $72 for fertilizer and pesticides, $48 for medicine, medical services, $36 for local taxes; $7 for road building and improvement; $4 for power station maintenance; $6 for education and culture and $60 for cloth and clothes.

The family's income was $674: $12 from the sale of 100 kilograms of rice; $54 from the sale of 100 kilograms of chilies; $25 from the sale of 150 kilograms of rapeseed; $163 from selling pigs; $34 from the sale of 20 ducks; $145 from the father’s construction work; and $241 in remittances from a daughter working in southern China in a factory.

Many villagers have become dependent on the money family members earn as migrant workers and factory employees. There is often prestige attached to how many children a family have that are working outside the village that and how much money they send home.

Markets are often the center of economic and social life. Peasants hawk melons and potatoes and other food crops from blankets spread on the ground the back of ox carts. There are also snake oil salesmen, opera troupes, fortunetellers, watermelon sellers, billiard table operators, noodle stalls, and gambling tables. Choosy Chinese shoppers prefers honest, straightforward sellers.

"Market day is magic for millions of Chinese peasants who see civilization only three or four times a month when they pack their bundles and their hopes and head for town," wrote Patrick Tyler in the New York Times. "They stream out of the mountains on bike or on foot or in a packed horse carts, cheerfully suffering the burdens of their rice bags, pork shanks or spinach heaps. They travel for hours along bumpy roads, some just hoping to make a successful purchase of a needed farm tool, a well-woven basket or a hand-fitted wooden water pail to balance on a shoulder pole."

Li Ziqi, a Chinese Villager, Sets Guinness YouTube World Record

Li Ziqi, a villager in Sichuan Province, set a Guinness World Record for the Chinese-language channel on YouTube subscribers in 2021. Her videos show her doing farm chores, growing and gathering food, and preparing it. She is greatly admired for cooking skills and the way she make kimchi. The South China Morning Post reported: She was listed in the records in July with 11.4 million subscribers and had gone up to 14.1 million by the end of January, the post said. “The poetic and idyllic lifestyle and the exquisite traditional Chinese culture shown in Li’s videos have attracted fans from all over the world, with many YouTubers commenting in praise,” the post said. “The culture that her videos conveyed is travelling further.” [Source: Phoebe Zhang, South China Morning Post, February 3, 2021]

Chinese netizens reacted with praise, with a related hashtag on Weibo being read over 720 million times by Wednesday morning. “Li definitely made Westerners understand Chinese culture better, she has done a great job exerting soft power,” one comment said. “When I watched her videos, I felt calm, quiet, beautiful. In her videos, I could hear birds chirping, that’s the sound of nature,” another said.

“In 2012, Li decided to stay in her hometown in southwest China’s Sichuan province to take care of her sick grandmother, who had raised her. In 2015, she decided to make cooking videos to show her life in the picturesque countryside. When making food, she shows the entire process of how the crop is grown, harvested and cooked. The images of her doing chores such as feeding animals, preparing a meal for her grandmother or making silk garments are picture-perfect, portraying a simple life in the countryside.

“Li has turned her videos into a successful business, with more than five million fans following her online shop on Taobao, operated by the Alibaba Group. “She launched her YouTube channel in 2017, with a video on making a dress out of grape skins. Her videos portray a picture postcard image of China.

Li’s rural videos strike a chord with her followers. “I love watching grandma just sitting in the sun and eating all the delicious things Lizi makes her,” one commenter said. “This channel has an aesthetic sensibility beyond anything I have ever seen. Thank you Li Ziqi for sharing your abundant skills and appreciation of all aspects of nature,” another said. She posted a video in January 2021 making pickled vegetables, using the hashtags #ChineseCuisine and #ChineseFood, and found herself embroiled in an international social media storm, with South Korean and Chinese netizens arguing over the origins of kimchi.

Image Sources: 1) Pole man, Bucklin archives ; 2) Chores, Agroecology ; 3) Sewing ladies, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; 4) Others Beifan.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021