CHINESE SOCIETY

Chinese society was shaped for a long time by Confucianism and then by Communism and now by making money. "Diwei" (“status”) is all-important in modern China. Otherwise China is a very diverse place and the Chinese are a diverse group of people. Attitudes, feeling and values vary from individual to individual, group to group and region to region and it is difficult to make generalizations. Chinese society has gone through enormous changes in the past century and changes in daily and economic life have been particularly rapid in the past decade. A popular expression that describes how fast society is changing goes: "He who thinks is lost."

China, the world's largest society, is united by a set of values and institutions that cut across extensive linguistic, environmental, and subcultural differences. Residents of the southern and northern regions of the country might not understand each other's speech, enjoy each other's favorite foods, or make a living from each other's land, and they might describe each other with derogatory stereotypes. Nonetheless, they would regard each other as fellow Chinese, members of the same society, and different from the Vietnamese or Koreans, with whom some Chinese might seem to have more in common. [Source: Library of Congress]

Most societies in Southeast Asia are characterized by bilateral descent while societies in China, Korea and Japan are characterized by patrilineal descent. In the former sons or daughters may inherit property while in the latter only sons inherit property and in many cases traditionally have taken up the same trades as their fathers In the Maoist era in China the Communist Party made many decisions about a person's private life, telling them when and who to marry, what birth control methods to use, and what jobs to take. Today, life is much more about choice than it used to be. People now have more say in choosing their jobs, their spouses and they things they want to buy though arguably their lives are still more constrained than those of people living in the West.

“Chinese society, since the second decade of the twentieth century, has been the object of a revolution intended to change it in fundamental ways. In its more radical phases, such as the Great Leap Forward (1958-60) and the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), the revolution aimed at nothing less than the complete transformation of everything from the practice of medicine, to higher education, to family life. In the 1980s China's leaders and intellectuals considered the revolution far from completed, and they intended further social change to make China a fully modernized country. It had become increasingly clear that although many aspects of Chinese social life had indeed undergone fundamental changes as a result of both political movements and economic development, the transformation was less than total. Much of the past either lived on in modified form or served to shape revolutionary initiatives and to limit the choices open to even the most radical of revolutionaries.

Human Development Index: 85th (rank out of 189 countries): (compared to 1 for Norway, 13 for the United States and 189 for Niger). The Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite statistic of life expectancy, education, and income per capita indicators. A country scores higher HDI when the life expectancy at birth is longer, the education period is longer, and the income per capita is higher [Source: United Nations Development Programme's Human Development Report, Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: VALUES AND NORMS IN CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIANISM, FAMILY, SOCIETY, FILIAL PIETY AND RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com ; 19TH CENTURY CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM factsanddetails.com ; INCOME DISPARITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SUICIDES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EVERYDAY LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE YOUTH AND "LYING FLAT" factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FAMILY IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com ; SINGLE ADULTS AND LEFTOVER WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SINGLE MOTHERS, MARRIED WITH NO CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com ; SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; END OF THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PEOPLE Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CHARACTERISTICS Factsanddetails.com/China ; REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; RELIGION, FOLK BELIEFS AND DEATH ( Main Page, Click Religion) Factsanddetails.com/China

Good Websites and Sources: Book: Civil Discourse, Civil Society and Chinese Communities by Randy Kluver, John Powers/books.google.com ; Book: Studies in Chinese Society by Arthur Wolfe, Emily Ahern, Emily Martin/books.google.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao on Classes in Chinese Society marxists.org ; Disparity of Income bbc.co.uk ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Book: "Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance" edited by Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden (Routledge, 2010)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Why China Leads the World: Talent at the Top, Data in the Middle, Democracy at the Bottom" by Godfree Roberts Amazon.com; "From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society" by Xiaotong Fei , Gary G. Hamilton, et al. Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “The Individualization of Chinese Society” by Yunxiang Yan Amazon.com; “Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors” by C.K. Yang Amazon.com; “Gods, Ghosts, and Gangsters: Ritual Violence, Martial Arts, and Masculinity on the Margins of Chinese Society” by Avron Boretz Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society: Changes and Transformations” by Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang Amazon.com; “Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century” by Susan Naquin and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com; “A History of Chinese Civilization” by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com

Social Stratification in China

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: Confucian philosophy endorses a hierarchical class system. At the top of the system are scholars, followed by farmers, artisans, and finally merchants and soldiers. A good deal of social mobility was possible in that system; it was common practice for a family to save its money to invest in the education and advancement of the oldest son. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

When the communists took control, they overturned this traditional hierarchy, professing the ideals of a classless society. In fact, the new system still has an elite and a lower class. Society is divided into two main segments: the ganbu, or political leaders, and the peasant masses. According to the philosophy of the Communist Party, both classes share the same interests and goals and therefore should function in unison for the common good. In reality, there is a large and growing gap between the rich and the poor. Weathy people live in the cities, while the poor tend to be concentrated in the countryside. However, farmers have begun to migrate to the cities in search of work in increasing numbers, giving rise to housing and employment problems and creating a burgeoning class of urban poor people.

Cars are a symbol of high social and economic standing. Comfortable living accommodations with luxuries are another. Many government employees who could not otherwise afford these things get them as perks of the job. As recently as the 1980s, most people dressed in simple dark-colored clothing. Recently, more styles have become available, and brand-name or imitation brand-name American clothes are a marker of prosperity. This style of dress is more common in the cities but is visible in the countryside among the better-off farmers.”

TV Dramas as a Means of Stratifying Chinese Society

In the early 2010s, British dramas like “Sherlock” and “Downton Abbey” were drawing viewers in China. The Wall Street Journal reported at the time: “Comparing levels of discussion on different social media sites, a recent study from entertainment research company Entgroup (in Chinese) found that British dramas were catching on among China’s wealthy and well-educated youth. While virtually unknown on the Chinese Internet a few years ago, British dramas now account for more than 9 percent of foreign TV discussion across Chinese social media sites, compared to around 28 percent for Korean soap operas, according to the study. [Source: Wall Street Journal, July 3, 2013]

“On websites that cater more exclusively to white collar workers and college students, the number for British shows jumps to more than 13 percent, versus less than 1 percent for Korean soaps, according to the Entgroup report, which found that more than half of those who followed British dramas held at least a bachelor’s degree. That puts British shows at the top an increasingly snobbish pop-cultural hierarchy in China — described by local media as the “disdain chain” (in Chinese) — in which British drama fans look down on fans of American shows, who themselves look down on Korean soap fans, who in turn look down on fans of domestic dramas. China Real Time has more.

On Chinese viewers that complained about popular American television shows being banned, Ying Zhu wrote in in the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time blog: “Let’s not fool ourselves about the motivations of those protesting the ban...The backlash is more about a desire to connect with cutting-edge global trends than it is an effort to, say, demand more political openness within China. The motivation is similar to wanting access to French wine and cheeses, Italian fashion and German cars — access to such goods brings about instant consumer gratification. [Source: Ying Zhu China Real Time blog, Wall Street Journal, May 19, 2014. Ying Zhu is professor of media culture at the City University of New York and an expert on Chinese media & society]

Important Components of Chinese Society

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: Important groups found in China today include “village farmers working hard on the land despite slumping returns, the floating population struggling to send home earnings to give their children a better life, the xiagang [former workers in state enterprises] looking to the state they once depended on as a source of authority (even as they prowl labour markets for odd jobs to feed their children), the ‘new workers’ striving to pull themselves and their family up the social ladder, all attest to a host of traditional values permeating Chinese society that centre on family, work ethics, education and hopes for a better future [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011] . Psychologically and economically, China today is in some ways a perfect illustration of the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s famed ‘hierarchy of needs’. Among the poorest, survival is paramount. China’s subsistence farmers, xiagang day-labourers and floating population urban hunter-gatherers mostly want clean water to drink, shelter to keep them warm and dry, enough food to avoid starvation, a bit of secure income, and perhaps the ability to see a doctor if they get sick. In Maslow’s terms, they spend their days at the bottom of the pyramid, dealing with physical survival and personal safety and security.

Among the poor are much of the floating population, who support their family back in the villages out of their meagre urban wages. Many xiagang workers, many of them middleaged or older, after sweating all day in the labour markets and caring for their family in the evening, still struggle in nightschools to learn English, or how to use computers, so they too can join the ranks of more sophisticated workers. And more villagers leave the farms and join the floating population every day.

For China’s middle class, survival and basic personal security are pretty well given. They spend their days largely in the middle of Maslow’s pyramid, dealing with family and children, self-esteem and the esteem of others. This, of course, makes them perfect targets for marketing campaigns based on family happiness, health and closeness, as well as on individual and social esteem. Spend any time watching successful advertisements on Chinese television and you will see a range of familiar images from similar advertisements in the US: happy couples, smiling children, nice homes, or chic youngsters with chic friends. These basic messages reflect a similar reality: most target consumers in China, like A recent study, by advertising giant Young & Rubicam, found most target consumers in the that the two core motivators for US, want to feel loved, close to many Chinese youth today are the their families, and respected by urge to live a materially better life than their parents, and the urge themselves and their peers. to contribute to their families.

At the highest levels of Chinese society — a combination of goals different in several nuances from society, these values play out as those that motivate the average well — hence the markets for young American today. luxury cars, nice villas, expensive family vacations and private schools. But the higher levels of Chinese society are also most likely to be concerned with the self-actualisation at the top of Maslow’s pyramid: creativity, spontaneity, knowledge and acceptance of the world and so on. Thus in China as in many societies, the artists, musicians and poets are most often children of the middle-to-upper classes, as are the scientists, entrepreneurs, government leaders and others who lead China’s growth.

Space and Crowds in China

Chinese are rarely alone. They like crowds and street life, they keep the doors of their homes open, and like many other Asians, they enjoy traveling in groups and going where everyone else is going. The Chinese fondness for crowds is summed up with the word renao, meaning “hot and clamorous.” The Chinese are able to live together in close quarters with a minimum of friction. What would seem like an unbearable lack of privacy and space to Westerns seems cozy and neighborly to Chinese. New arrivals are told to pull up a seat rather than rebuffed.

Many Chinese customs, values and personality traits arise from the fact that Chinese live so close together in such a crowded place. Everyday Chinese navigate and maneuver their way on crowded sidewalks and roads and sit elbow to elbow in small restaurants. If there weren't strict rules and a high degree of tolerance for things Westerners perceive as rude behavior, people would be at each other's throats more than they already are.

Personal space is hard to find in China and thus the concept of privacy is more of state of mind than a condition of being alone. The Chinese are very good at shutting out the world around them and making their own privacy and losing themselves in their thoughts or what they are doing while surrounded by people. Chinese have a hard time understanding the desire of some Western too be alone, sometimes interpreting this desire as arrogance.

Privacy and a Lack of Privacy in China

Privacy isn't as important to Chinese as it is to Westerners. It is not unusual for a passenger on train to share his or her four person compartment with a 78-year-old women and a honeymooning couple doing what newlyweds usually do on their first night together. On the trains you also see people doing their washing, partying to loud rock music from cassette players, playing cards, and lounging around in their underwear or pajamas. Communists taught people to eschew secrets and share everything. In Beijing it became common for people to socialize seated on toilets with no doors or partitions. The playwright Guo Shixing told the Los Angeles Times, “Privacy is a concept only recently adapted from the West. Everyone was supposed to be equal. And if you had anything different from the others you became the focus of attention. By sharing the toilet since childhood, you lost all shyness.”

David Bandurski wrote in Supchina: “In a piece called “The Long March to Privacy, ” The Economist once talked about the advancements Chinese had made in their attitudes toward privacy. After decades in which virtually every aspect of their lives had been “an open book, ” subject to constant government scrutiny, Chinese citizens were now “beginning to bristle at the intrusiveness of nosy employers, data-mining marketers and ubiquitous security cameras.” That article ran in 2005, when China was on the cusp of the mobile digital revolution. Today, as big data promises a commensurate revolution in surveillance capabilities, privacy in China (as elsewhere) faces enormous new challenges. And so, taking a fresh look last month, The Economist voiced concern over plans in China for a far-reaching “social credit system, ” a bold experiment in digital social control applying financial, social and possibly even political data points to the lives of all citizens.” [Source: David Bandurski, Supchina, January 3, 2016]

But perhaps the worst "privacy horror story is unfolding right under the noses of Chinese citizens — namely, the sale of personal data through an information black market that appears to be plugged into national police and government databases already. In a December 12, 2015 expose in Guangzhou’s Southern Metropolis Daily, reporters Rao Lidong and Li Ling carefully documented their successful attempts to obtain personal information about consenting colleagues through “tracking” services advertised online. For a modest fee of 700 yuan, or about 100 dollars, the reporters were able to obtain an astonishing array of information based on one colleague’s personal ID number, including a full history of hotel rooms checked into, airline flights taken, internet cafes visited, border entries and exits, apartment rentals, real estate holdings — even deposit records from the country’s four major banks. But that wasn’t all. The reporters were also able to purchase live location data on another colleague’s mobile phone, pinpointing their position with disturbing accuracy.

In 2020, Vincent Ni and Yitsing Wang of the BBC wrote: “On a busy Monday afternoon in late October, a line of people in reflective vests stood on Happiness Avenue, in downtown Beijing. Moving slowly and carefully along the pavement, some crouched, others tilted their heads towards the ground, as curious onlookers snapped photos. It was a performance staged by the artist Deng Yufeng, who was trying to demonstrate how difficult it was to dodge CCTV cameras in the Chinese capital. As governments and companies around the world boost their investments in security networks, hundreds of millions more surveillance cameras are expected to be installed in 2021-and most of them will be in China, according to industry analysts IHS Markit.” [Source: Vincent Ni and Yitsing Wang, BBC November 25, 2020]

Village Society in China

Village society is often tradition bound and built around loyalty to family, extended families and hometowns. The basic political and social units in village societies are the tribe, clan, family and the village. Elders and leaders wield much authority. Many villages are made of a single extended clan often with a single name such as Ma. Most of the world's societies are patrilineal, meaning that things like social status, property and family names are all inherited along patrilineal lines — passed down from father to son. Kin groups are also usually patrilineal. This means that relatives of the father of an individual are welcomed as family while those of the individual’s mother are welcomed as guests.

Traditional societies are often based on three elements: prestige, competition between clans and individuals, and the concept of reciprocity of gifts of money, goods or services. Prestige is measured in terms of political power, knowledge, material possessions and the ability to accomplish feats. Villages were traditionally ruled by the patriarch of the clan. Often times most of the people in a village were related and most people had the same family name. The patriarch settled disputes and oversaw community matters. Meetings were held in village clan temples, where the ancestral tablets (genealogical records) were kept.

Village societies are held together by systems of community responsibilities in which everyone agrees to help everyone else with agricultural chores such as planting, harvesting, and building irrigation ditches as well as things like constructing community buildings. Leaders make sure all these tasks are done efficiently for everyone in the community and no one sluffs off. The social code that defines community responsibilities is often combined with religion, mythology, tradition, morality and tribal law. Leaders are sometimes believed to be aided by supernatural forces in carrying out the community's tasks.

Village life can be very competitive. There is often a struggle for resources bubbling just under the surface. Villagers know each other well and conflicts seldom arise by accident. Slights are assumed to be deliberate and they often are. Once a conflict gets going it often persists and structures are created to manage it not resolve it. According to the Encyclopedia of Culture: “Villagers live by tradition and lack the incentives, knowledge, or security to make changes. Change is seen as a disruptive force and threatening to the harmonious relationships that villagers have established with their environment and their fellow villagers.”

Clans, Village Councils and Headmen in China

The most important social institutions in villages are the clan, the village council and headman, or chief. Villages are composed of perhaps five to 25 clans, with other members of clans sometimes living in other villages, sometimes not. Clan leaders make up the village council. Clans are ranked and the leader of the highest clan is the headman (leader of the village) and the most prominent member of the village council.

Villages — and cities, towns and communities — have traditionally been dominated by powerful families and clans. Clans are usually composed of several extended families that are related to one another and usually have a common ancestor that often provides the clan members with a family name. Social status is determined by rank of a clan and the position within the clan. Status within the clan is determined by family background and meritorious deeds performed for the clan.

The headman is the highest moral and legal authority in the village. He supervises the welfare of the community, settles disputes, makes decisions on water allocation, education and fishing rights and sometimes advises villagers on who to vote for. But he is by no means a dictator. Before carrying out a decision he must have the endorsement of other clan leaders in the village council. Many villages have a council house, where village people (usually men) meet to discuss problems and issues facing the village.

In some societies the headman is also a shaman, healer and religious leader. In other societies healing and religious duties are taken care by someone else. Some headmen are authoritarian; others work closely with their councils; but ultimately they are the ones who have to make tough decisions and the buck stops with them. Many villages have a means of getting rid of a headman if he becomes too unpopular. There are not many examples of headwomen. There is often some kind of liaison that acts as an intermediary between the village and the local and national government. See Local Government, Government

Disparity of Income in China

In the Mao era there was little income disparity and few rich people. Forced egalitarianism prevailed. The Asian countries in with the lowest income disparity between rich and poor (determined by how many times more income the richest 20 percent of the population has than the poorest 20 percent) in the 1990s were: 1) Sri Lanka (4.4); 2) Indonesia (4.9); 3) South Korea (5.7); 4) China (6.5), Philippines (7.4)...compared to 9.0 in the U.S., 15.5 in Thailand and 32 in Brazil.

A poll conducted by the Pew Research Center before the 2008 Olympics found that 89 percent of the Chinese interviewed said they were concerned about the gap between rich and poor. As China’s economy has rapidly grown, it has gone from having one of the lowest income disparities of incomes to one of the highest in a relatively short amount of time. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, in the mid 2000s the top 10 percent of the Chinese population controlled 45 percent of the country’s wealth while the poorest 10 percent had 1.4 percent and had incomes less than 1/12th of those of the richest 10 percent. By some accounts the disparity now is greater than it was before the Communists took power in 1949. Income disparity is also geographical phenomena, with people in the richest parts of the country earning 10 times more than those in the poorest parts. Much of the China’s wealth is concentrated in the coastal cities in eastern and southern China. The interior for the most part remains poor.

Frustration over the widening income gap has resulted in bitterness among have nots and evoked nostalgia for the old days. A 48-year-old truck driver told the Los Angeles Times, “Many people our age are psychologically unbalanced. What’s so great about letting a few get rich while so many more are dragged into poverty” I really miss the Mao period when things were equal.” Sociologists call the phenomena “reactive deprivation” and say the problem “is especially true when its personal — people see a neighbor get rich even though they used be classmates and are just the same. Chinese patience is perhaps most pronounced when it comes to money.”

See Separate Article INCOME GAPS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Inequalities and the Party-Connected Status Quo in China

The 2015 China Family Panel Studies report by the Institute of Social Science Survey at Peking University found that family background plays an important role in determining people’s level of schooling, especially parents’ educational attainment, which is true in many places. But in China, Chris Buckley wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere, “political privilege is also an important factor. Whether your father is a member of the Communist Party — almost mandatory for government officials — is a powerful determinant of educational attainment, even, the study found, for Chinese born after 1980 under the market-oriented policies of Deng Xiaoping. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, January 27, 2016]

“Having a father who is a party member also has a clear, positive effect on an individual’s years of schooling, ” the study said. (A mother’s party membership status has no discernible impact, it also found.) Discrimination against girls has weakened, but it remains a powerful factor in the opportunity for schooling, the study also found. On average, boys receive 1.5 more years of schooling than girls.

“Unequal access to health care has also been a source of dissatisfaction for many Chinese, especially residents of the countryside and small towns where medical insurance has been less widely available and where there are fewer doctors and hospitals.“The survey found that the Chinese government’s efforts to spread health insurance had made a difference. Growing numbers of rural residents have some, though it is usually not as generous as policies held by many city dwellers. And women also do worse than men. “Females, rural residents and low-income groups all enjoy fewer health care subsidies and pay a higher proportion by themselves, ” the study said.

Unfairness of Life in China

One of Peter Hessler Sichuan University wrote: China’s system cannot afford individualized education, caring for one’s all-around and healthy growth. . . . Our system is merely a machine helping the enormous and somewhat cumbersome Chinese society to function — to continuously supply sufficient human resources for the whole society. It is cruel. But it is also probably the fairest choice under China’s current circumstances. An unsatisfying compromise. I haven’t seen or come up with a better way. [Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, May 9, 2022]

Hessler said his students “often used the term neijuan, or involution, a point at which intense competition produces diminishing returns. For them, this was unavoidable in a vast country. For one writing assignment, a freshman engineering student named Milo returned to a Chongqing auto-parts factory that he had first visited eight years earlier, for an elementary-school project. This time, when Milo interviewed the boss, he was struck by how old the man looked. The boss explained that booming business required frequent travel and many alcohol-fuelled banquets with clients. “I had no time to take care of my family,” he told Milo. “My kids do not understand me and even dislike me, since I seldom show up. What’s more, after drinking so much alcohol, I sometimes have a terrible stomachache.”

“On the factory floor, a foreman whom Milo remembered said that the workforce had been reduced by a third, because of automation. Milo titled his essay “Farewell, Old Factory,” and he concluded Everyone in the society must try their best to follow the world’s trends. This is a colorful and fascinating world, but this is also a cruel world. If you are not good enough, you will be eliminated without a trace of pity.”

Violence in China

Jia Zhanghe, who made a film about violence in China called “A Touch of Sin”, told the New York Times: In the early 2010s, “I started using Weibo, and Chinese society also became more interested in using Weibo, China’s Twitter. It’s had a big impact on the lives of Chinese people. The biggest impact I think is that now if something happens, no matter where it is in China, it can be seen by people immediately. And I feel that the way I understand China’s reality has also changed, because now I can see these things that are happening all around China on Weibo... There are good stories and there are bad stories. But for me, I slowly began to see the problem of individual violence in society. There are many tragedies or social problems in which people ultimately rebel, and this becomes a very big tragedy. So I began to pay more and more attention to this problem because, frankly speaking, I feel that the Chinese people really don’t understand the problem of violence because society has never had a widespread discussion of the problem. [Source: Interview with Edward Wong, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, October 18 and 21 2013]

“Especially in films, violence used to be restricted. Of course, there are two aspects of this. One is the censorship of films. In the past they didn’t really allow too much violence in movies, especially when the violence was closely interrelated with society. Then there is the cultural convention in China where we are not very willing to look back on or confront unpleasant events. Obviously, all of these violent events are unpleasant. But for me, it is not enough for the news media to report on these violent incidents. I think what films can do is provide an emotional understanding, and in the one or two hours of a film we can try to understand these incidents. From that time on, I really wanted to direct this kind of movie.

Another reason is that each story is really a very extreme one, because violence is itself extreme. An extreme story is not necessarily something that happens all the time. So it often gives the impression of being an isolated case, and it might seem like this person was simply in very particular circumstances that led to this tragedy. But what we see in China today is that these kind of events happen all the time. They are no longer rare events. There are profound social reasons why they occur. So I feel that by using multiple stories we are telling people that this isn’t necessarily an exception, nor is this an isolated and extreme story. That these kind of stories happen in China all the time.

“For example, after I returned from Cannes, there was very unfortunate news. There was an explosion in a bus in Fujian, then the gun rampage at a Shanghai factory, and then the Beijing airport explosion. There have been many commentaries that have said “A Touch of Sin” is a kind of prophetic piece. But it’s not really prophetic. I wasn’t predicting anything. Rather, I saw circumstances in present-day Chinese society that make us feel rather uneasy. Through the film, I hope to raise people’s awareness as well as present my own impression of these circumstances. So these four characters don’t necessarily represent individual cases so much as something we should recognize as a social problem.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Despite the frequency of such incidents appearing on Weibo, however, it’s not clear that violence is on the rise in China. Jia’s vision of his country is reminiscent of that of worried Americans, who are sure that their cities are rampant with crime, even though crime rates have fallen steadily for decades. In China, street crime is more common than it was in the Mao era, but Chinese cities are safe and killings rare. The echoing effect of social media may be distorting our perception, raising some of the same questions we may ask about the rise in reported rapes in the West: does it mean rape is increasing, or that more people are reporting it, or simply that reports of it can now spread faster and more widely? Increased reporting is important, as it implies changing social norms, but Jia seems to be arguing the harder-to-prove point that violence in China is up based on the notoriously unscientific indications of social media postings. This approach lends his storytelling a sensational feel. At times, his characters seem as if they might have come from the pages of publications like the Legal Evening News [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 25, 2013]

Change and Suicide in China

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian in 2018: In my 58 years, I have experienced three dramatic changes, and each one has been accompanied by a surge in suicides among officials. The first time was during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. At the start of that period, many members of the Chinese Communist party woke up one day to find they had been purged: overnight they had become “power-holders taking the capitalist road”. After suffering every kind of psychological and physical abuse, some chose to take their own lives. In the small town in south China where I grew up, some hanged themselves or swallowed insecticide, while others threw themselves down wells: wells in south China have narrow mouths, and if you dive into one headfirst, there is no way you will come out alive. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018. Yu Hua is a famous writer in China, considered a candidate for the Nobel Prize. He is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant”, “To Live” and “Brothers.”]

“In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, many people from the lowest tiers of society formed their own mass organisations, proclaiming themselves commanders of a “Cultural Revolution headquarters”. These individuals — rebels, they were called — often went on to secure official positions of one kind or another. They enjoyed only a brief career, however. Following Mao’s death in 1976, the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution and the emergence of the reform-minded Deng Xiaoping as China’s new leader, some rebels believed they would suffer just as much as the officials they had tormented a few years before.

“Thus came the second surge in suicides — this time of officials who had clawed their way to power as revolutionary radicals. One official in my little town drowned himself in the sea: he smoked a lot of cigarettes first, and the stubs littering the shore marked the agony of indecision that preceded his death. This was a much smaller surge in suicides than the first one, because Deng was not out for political revenge, focusing instead on kickstarting economic reforms and opening up to the west. This policy led in turn to China’s economic miracle, the downside of which has been environmental pollution, growing inequality and pervasive corruption.

“In late 2012 came the third dramatic change in my lifetime, when China entered the era of Xi Jinping. No sooner did Xi become general secretary of the Communist party than our new leader launched an anti-corruption drive, the scale and force of which took almost everyone by surprise. The third surge in suicides followed. When officials who had stuffed their pockets during China’s breakneck economic rise discovered they were being investigated and realised they could not wriggle free, some put an end to things by suicide. In cases involving lower-ranking officials who were under investigation but had not yet been taken into custody, the government explanation was that their suicides were triggered by depression. But, if a high-ranking official took his own life, a harsher judgment was passed. On 23 November 2017, after Zhang Yang, a general, hanged himself in his own home, the People’s Liberation Army Daily reported that he “had evaded party discipline and the laws of the nation” and described his suicide as “a disgraceful action”.

“These three surges in suicide demonstrate the failure and impotence of legal institutions in China. The public security organs, prosecutorial agencies and courts all stopped functioning at the start of the Cultural Revolution; thereafter, laws existed only in name. Since Mao’s death, a robust legal system has never truly been established and, today, law’s failure manifests itself in two ways. First, the law is strong only on paper: in practice, law tends to be subservient to the power that officials wield. Second, when officials realise they are being investigated and know their position won’t save them, some will choose to die rather than submit to legal sanctions, for officials who believe in power don’t believe in law. These two points, seemingly at odds, are actually two sides of the same coin. The difference between the three surges in suicide is this: the first two were outcomes of a political struggle; framed by the start and the end of the Cultural Revolution. The third, by contrast, stems from the blight of corruption that has accompanied 30 years of rapid economic development.

Change on the County Level in China

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian: “When I turn to the road of nostalgia, I think of how my home county of Haiyan has transformed. When I was a boy, Haiyan had a total population of 300,000, with only 8,000 living in the county town itself. Now, the county has a population of 380,000, of whom 100,000 live in the county seat. Urbanisation has created a lot of problems, one of them being what happens after farmers move to cities. Local governments have expropriated large swathes of agricultural land to enable an enormous urban expansion program: some of the land is allocated to industry in order to attract investment, build factories and boost government revenues, but most of it is sold off at a high price to real-estate developers. The result is that high-rise apartment buildings now sprout in profusion where once only crops grew. After their land and houses in the countryside are expropriated, farmers “move upstairs” into housing blocks that the local government has provided in compensation. In wealthy counties, some farmers may be awarded up to three or four apartments, in which case they will live in one and rent out the other two or three; others may receive a large cash settlement. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018]

“But the questions then become: how do they adjust to city life? Now disconnected from the form of labour to which they were accustomed, what new jobs are there for them to do? Some drive taxis and some open little shops, but others just loaf around, playing mahjong all day, and others take to gambling and lose everything they have. Every time a community of dispossessed farmers settles into a new housing project, gambling operations will follow them there, because some of the residents will be flush with cash after the government payouts. In China, it is forbidden to open gambling establishments, but this doesn’t stop unlicensed operators from cramming their gambling accessories into a few large suitcases and lugging them around these new neighbourhoods, where they will talk their way into the homes of resettled farmers. The gambling outfits play hide-and-seek with the police, setting up shop here today, shifting to a new spot tomorrow.

“What is the situation back where the farmers came from — the houses in the countryside now expropriated but yet to be demolished? Peasants often have dogs to protect the home and guard the property. When peasants move to the cities, they no longer need guard dogs, so they leave them behind. And so you see poignant scenes in those empty, weed-infested farm compounds, as those abandoned dogs, all skin and bones, faithfully continue to perform sentry duty, now rushing from one end of the property to the other, standing on a high point and gazing off into the distance, their eyes burning with hope, longing for the past to return.

Challenges for Chinese Economic Society

Michael Keane of Queensland University of Technology wrote: “In China these days much discussion focuses on how Chinese society can ‘upgrade’, particularly in regard to the millions of people with low levels of education living outside the large urban centres. Moreover, the aging of China’s population is having a direct impact on the numbers of people registered in work. Such a decline is to be expected over time but combined with increasing minimum wages and growing average incomes, the nation is moving inexorably closer to what economists call the ‘Lewis Turning Point.’ This occurs when the economy can no longer create wealth by adding cheap labour. As Matthew Crabbe from Access Economics points out, the challenge now is to generate added-value through increased efficiency, innovation and high-value production. [Source: Michael Keane, Queensland University of Technology, Asian Creative Transformations, December 2, 2014 ||||]

“In China GDP dominates everything. While economic data may often be suspect there is no doubt that the government aspires to keep GDP indicators stable. In the past this has been achieved largely by the strength of ‘made in China’ exports. But like many tales of progress, there is more than one side. Despite the suggestion that technology is now changing China and that China is moving closer toward developing a service-led economy, it is clear that the Chinese economy still relies heavily on physical infrastructure and physical labour. Hundreds of millions of people want work: without the guarantee of work China would have social disruption on a large scale. This is the fear that keeps the government on its toes.” ||||

“China is a more technologically connected society than ever before; it has leapfrogged stages of development by adopting and adapting technologies. Most Chinese are internet users. In 2012, according to Access Economics 242 million people purchased goods and services online; 55.4 million of these purchases were transacted on mobile phones. According to a report by McKinsey & Company there are 6 million e-merchants listing products on Taobao. This is having a strong impact on private consumption while at the same time accelerating innovation in services, in advertising and marketing, payment systems, warehousing and IT systems. This surely is a manifestation of the creative economy however defined—and it is driven by technological innovation. ||||

“Digital technologies are transforming the relationship between culture, creativity and innovation. This is further exemplified by the so-called BAT grouping of companies: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. Thanks to the entry of these cash-rich IT-based companies into the market new forms of production, distribution and consumption have evolved for screen-based content. In this instance convergence, and the greater latitude provide to new media than to traditional media by China’s regulators, have allowed incumbents to experiment with form, content and business models. The developments in media content that are now happening in China reflect global changes. BesTV, Youku-Tudou, iQIYI, PPTV, Netease, and LeTV are China’s answer to Netflix, Hulu, Amazon and Google TV. They are commissioning and buying original content on an unprecedented scale. ||||

“These technologies are transforming Chinese culture and society and people’s ways of interacting with information. While dramatic changes have taken place in the way that people in China live, work, play and interact with government, employers, peers and family members, the fact remains that the development master plan is underpinned by a deep seated acceptance of the need for social order; for instance new regulations issued by the media regulator State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio and Television (SAPPRFT) early this year require all content streamed on video sites to undergo scrutiny. ||||

Alternative Lifestyles in China

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: Drop-Outs and Druggies, Artists and the Avant-Garde. As with any modern nation, China has many people living at the fringe of mainstream society not necessarily due to poverty (some are children from well-to-do families) but rather due to dedication to one or another alternative lifestyle. Given how out of character these groups seem to be relative to traditional images of China, they have grabbed more than their share of media coverage. Images of Chinese transvestites, fetus-eating Chinese ‘performance artists’, artists in communal colonies, Ecstasy parties and rockers pounding out the rhythms of China’s ever-more furious nightlife have captured the imagination of many writers and expatriates. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

“Based on how some expatriates spend their time, they may in fact believe the nocturnal denizens of the ‘bar streets’ of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou are the truest representatives of the modern Chinese. Certainly, these various fringe groups do represent some interesting trends in modern China. With the lifting of totalitarian political controls, the seamier side of life has returned to China along with the better access to travel, books and global performances. There is a flourishing drug trade in many Chinese cities today, and prostitution has returned with a vengeance.

“As in other nations, those ‘sin trades’ as practised in high society evoke sumptuous night-clubs, welldressed escorts and genteel whiffs of extremely expensive powders, while the lower-heeled versions involve a lot of dirty needles and exposure to AIDS. China’s more freewheeling atmosphere today also allows far more experimentation than in the past in virtually every musical and artistic genre, and every form of lifestyle choice. But when thinking about what they do and do not represent about China as a whole, it’s worth keeping in mind that they are still very much a fringe phenomenon.

Nostalgia and Looking to the Future in Modern China

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian: ““Wishing the past could return is a mood that is spreading through today’s society. Two patterns are typical. The more widespread of the two reflects the yearnings of the poor. China’s enhanced status as the world’s second largest economy has brought them few benefits; they continue to lead a life of grinding hardship. They cherish their memories of the past, for although they were poor then, the word “unemployed” was yet to exist. What’s more, in those days there was no moneyed class in a real sense: Mao’s monthly salary, for example, was just 404.8 yuan, compared to my parents’ joint income of 120 yuan. There was only a small gap between rich and poor, and social inequalities were limited. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018]

“A different form of nostalgia is prevalent among successful people who, having risen as high as they can possibly go, now find themselves in danger of tumbling off the cliff. Someone reported to me an exchange he had had with one of Shanghai’s ultra-rich, a man who had relied on bribery and other underhand methods to transform himself from a pauper into a millionaire. Realising he would soon be arrested and anticipating a long prison term, he stood in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows of his huge, lofty, luxurious office and looked down at the construction workers far below, busy building the foundation of another skyscraper. How he wished he could be one of those workers, he said, for though their work was hard and their pay was low, they didn’t have to live in a state of such high anxiety. Faced with the prospect of losing everything they have gained, such people find themselves wishing their spectacular career hadn’t happened at all, wishing they could reclaim the past.

“If the past were really to return — that past where you needed grain coupons to buy rice, oil coupons to buy cooking oil, cotton coupons to buy cloth, that past of dire material shortages, where the supply of goods was dictated by quotas — would those people who hanker for the past be happy? I doubt it.

“As I see it, when the poor pine for the past, this is not a rational desire — it is simply a way of venting their feelings, the voicing of a frustration that is rooted in their discontent with current Chinese realities. And when that other, smaller group of people who have been successful in government or business realise they are going to spend the rest of their life behind bars and wish they could reclaim the past, this sentiment springs only from a wistful regret: “If I had known this was going to happen, I wouldn’t have got myself into this mess.”

I’m reminded of a joke that’s been doing the rounds. Here is what’s unfair about this society: The pretty girl says: “I want a diamond ring!” She gets it. “The rich guy says: “I want a pretty girl!” He gets her. “I say: “I want a shower!” But there’s no water.

“That last situation, I myself have experienced. In my early years, more often than not, water would cut off just as I was having a shower — sometimes at the precise moment when I had lathered myself in soap from head to toe. All I could do then was hammer on the pipe with my fists, at the same time raising my head so that the final few drops of water would rinse my eyes and save them from smarting; as for when the water would come on again, I could only wait patiently and hope heaven was on my side. Back then, nobody would have seen water stoppages at shower-time as a social injustice, because in those bygone days, there were no rich guys, and so pretty girls didn’t get diamond rings and rich guys didn’t get pretty girls.

“It is often said that children represent the future. In closing, let me try to capture the changing outlook of three generations of Chinese boys as a way of mapping in simple terms China’s trajectory over the years. If you asked these boys what to look for in life, I think you would hear very different answers. A boy growing up in the Cultural Revolution might well have said: “Revolution and struggle. A boy growing up in the early 1990s, as economic reforms entered their second decade, might well have said: “Career and love.” Today’s boy might well say: “Money and girls.”

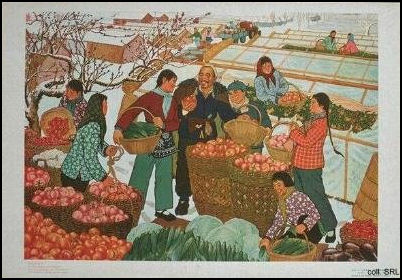

Image Sources: 1) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 2) Cinfucius images, Brooklyn College; 3) Street scene, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022