SHARED VALUES IN CHINESE SOCIETY

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: “Despite the centuries of war, revolution, economic reform and other transformations and dislocations that have changed so much about China, many traditional Chinese values still persist. This is unsurprising, of course; deep cultural values tend to be resilient. Both ancient Chinese traditions like Confucianism and Buddhism, and more modern traditions like socialist ethics, behave within China in similar ways to the Judeo-Christian tradition in Western societies. Some people are true believers, purposely organising their lives around these traditions. Others are ‘lapsed’, or perhaps never really believed at all. Still, these values affect most Chinese to some degree. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Among the key traditional Chinese values with persistent modern echoes are 1) Confucianism, 2) Focus on Education, 3) Buddhism and Daoism, 4) Family Values, 5) In-group and Out-group, anf 6) Nationalism and Internationalism “As early as 1958, historian Joseph R Levenson, in the classic “Confucian China and its Modern Fate”, explored the degree to which the intellectual and political ideals of traditional Confucian China were transformed by Maoism. Levenson and many since have observed that Confucian stress on the importance of calm, social order, strong leadership, clear hierarchies and moral example continue to affect Chinese culture. . Some believe that the tendency to revere tradition and authority in Confucian values precludes Western-style democracy in China; many have noted that relatively authoritarian governments prevail throughout the Confucian-influenced world, such as in Singapore and for a long time Korea.

“Many have commented on the ways that Chinese interpretations of Buddhism and local Chinese traditions of Daoism both encourage a culture of self-restraint and distrust of passion. Historian Orville Schell writes of the Chinese concept of ping, which is often translated as ‘peace’, but literally means ‘flatness’. The famously ‘inscrutable’ Chinese face is really a reflection of this ideal of calm self-restraint.

“Most Chinese parents and children grow up as a matter of course eating almost all meals together, supporting each other and sharing resources remarkably freely from a Western perspective. However the downsides of it can cause friction and misunderstandings. Even in adulthood, Chinese family members tend to involve themselves in each other’s lives (from choices of clothes and appliances to choices of a spouse and job) to a degree most Americans would find uncomfortable. An American friend of ours living with a Chinese man was amazed when the Chinese man wanted to turn over much of their joint savings to a needy cousin starting a business. The Chinese man, in turn, was amazed that his Western partner could possibly hesitate to share savings with family. “

See Separate Articles: CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; CONFUCIANISM, FAMILY, SOCIETY, FILIAL PIETY AND RELATIONSHIPS factsanddetails.com ; 19TH CENTURY CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM factsanddetails.com ; INCOME DISPARITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SUICIDES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EVERYDAY LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE YOUTH AND "LYING FLAT" factsanddetails.com ; FAMILIES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE FAMILY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FAMILY IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com ; SINGLE ADULTS AND LEFTOVER WOMEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SINGLE MOTHERS, MARRIED WITH NO CHILDREN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; WOMEN IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; ONE-CHILD POLICY factsanddetails.com ; SERIOUS PROBLEMS WITH THE ONE-CHILD POLICY: factsanddetails.com ; END OF THE ONE-CHILD POLICY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PEOPLE Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY AND CHARACTER Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHINESE PERSONALITY TRAITS AND CHARACTERISTICS Factsanddetails.com/China ; REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; RELIGION, FOLK BELIEFS AND DEATH ( Main Page, Click Religion) Factsanddetails.com/China

Good Websites and Sources: Book: Civil Discourse, Civil Society and Chinese Communities by Randy Kluver, John Powers/books.google.com ; Book: Studies in Chinese Society by Arthur Wolfe, Emily Ahern, Emily Martin/books.google.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao on Classes in Chinese Society marxists.org ; Disparity of Income bbc.co.uk ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Book: "Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance" edited by Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden (Routledge, 2010)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society" by Xiaotong Fei , Gary G. Hamilton, et al. Amazon.com; "Why China Leads the World: Talent at the Top, Data in the Middle, Democracy at the Bottom" by Godfree Roberts Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; “The Individualization of Chinese Society” by Yunxiang Yan Amazon.com; “Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors” by C.K. Yang Amazon.com; “Gods, Ghosts, and Gangsters: Ritual Violence, Martial Arts, and Masculinity on the Margins of Chinese Society” by Avron Boretz Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Understanding Chinese Society: Changes and Transformations” by Eileen Yuk-ha Tsang Amazon.com; “Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century” by Susan Naquin and Evelyn S. Rawski Amazon.com; “A History of Chinese Civilization” by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com

Rules, Goals and Harmony in China

Following rules is expected of the masses and is seen as putting the needs of the group ahead of the desires of individuals. "The problem of human equality," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin, “was not vivid in China. There, where tradition and customs ruled, the best qualities of life were viewed as products of Chinese tradition and customs."

Chinese put a strong emphasis on social harmony and group consensus. Traditional Chinese society was bound together by the two important concepts: 1) an agreement on community responsibilities that everyone in a neighborhood or village was party to; and 2) a method of organizing a community so that everyone helped everyone else with agricultural chores such as planting, weeding, harvesting and winnowing to make sure all these tasks were done efficiently for everyone in the community.

One American educator who has worked extensively in China told the Los Angeles Times, “It’s a very organized society, and when they set their mind to go a particular direction, they are able to drive things in that direction.”

There is strong emphasis on working hard together for common goals. One Chinese saying goes: “Endurance can turn a iron bar into a needle.” All one has to do is look at the Great Wall or the Grand Canal to see what this kind of thinking can achieve or look at the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution to see what it can destroy. Today you can see what happens when working hard together for common goals is applied to making money and producing economic growth.

Getting Chinese to work together isn’t always easy. There are a lot of conflicting interests, competition and one upmanship in China. One old Chinese saying goes: “eight departments can’t even cooperate in raising a pig.

Conformity, Exclusion and Individualism in China

Conformity is a strong force in China. Going against the grain is not encouraged and being labeled as different can be a crushing insult. You see few punk rockers in China and men with earrings, long hair or pony tails stand out. One of the worst fears of many Chinese is to be excluded from a group. The nail that sticks up get hammered down is an expression in China as it is in Japan.

Still, the Chinese also have a reputation of being more individualistic that other Asians. "The Chinese have never been able to organize collective effort with the sort of enthusiasm and efficiency of the Japanese," Scholar William McNeil once wrote. "There is a kind of ruthless individualism in Chinese life, a competitiveness and acquisitiveness." There are also so many people in China that individuals have to assert themselves or they get lost.

The Chinese have a highly developed sense of “in group” and “out group” which means they are more likely than Westerners to do things for their friends and less for strangers. Chinese can be rude to people they don’t know.

Stability and predictability have traditionally been valued more than flair and spontaneity; maintaining appearances has been more important than self expression. Expressing individual rights taken for granted in the West can land someone in jail or a labor camp in China.

In-Groups and Out-Groups Among Chinese

Seth Faison wrote in “South of the Clouds”: “In China, the sharp divide of insider and outsider dominates other distinctions. The insider, no matter how he fails, is accepted and welcomed in the fold. The outsider, regardless of character or achievement, is not to be trusted.”

Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: “In part as an extension of these strong family ties, Chinese people tend to view the world in terms of those to whom they do and don’t have connections and commitments. The philosopher Joseph Needham called this China’s ‘courtyard view of the world’. The Chinese, Needham observed, take meticulous care of their homes and of the inner courtyards viewed as interior to their homes, but think nothing of dumping garbage in the alley immediately outside. A similar mentality affects human relations. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

“Those ‘inside the courtyard’ — family, close friends, classmates, close colleagues — tend to be very close and to have stronger claims on each other than their counterparts in the US. This shows up in everything from readiness of personal loans and assistance in job-finding, to introduction of potential spouses, to the famous ‘connections’ (guanxi) that still characterise much of Chinese business. While not generally as strong as family ties, the other ‘courtyards’ within Chinese people’s lives remain powerful.

“At the same time, from a Western perspective, there is generally remarkably little regard among Chinese people for those ‘outside the courtyard’. Such phrases as wailairen (‘outsider’, often used to refer to newcomers, whether to a city or to a place of work) and waiguoren (‘foreigner’, but literally ‘person from an outside country’) attest to this ‘us-and-them’ sensibility. As many have observed, this has set a low bar in terms of expected treatment of strangers. Chinese people pushing and shoving their ways onto buses, ignoring people who might appreciate having a door held for them, and so on are partly results of China’s overpopulation and scarce resources, but also partly cultural. Most Chinese lacks any traditional phrase equivalent to the English expression ‘common courtesy’, though of course that idea has been translated into modern Chinese.

“With exposure to new ideas, such traditional ‘us-them’ attitudes are starting to shift in China. As present, though, from the Western perspective, Chinese people are a little over-involved and meddling in their relations with family and friends, and surprisingly rude to strangers. Of course, from the Chinese perspective, in a commonly repeated phrase, Westerners ‘treat strangers like friends and their family like strangers’. There is no doubt some truth to both perspectives. There is also some degree of ‘When in Rome, do as Romans do’. If you ever hope to get into a crowded subway or elevator in China, you too may need to learn to sharpen elbows.”

Individualism Versus Collectivism in China

There is a Chinese proverb that goes: “The bird who sticks out his head gets shot." Behavioral and sociological test often show that Americans emphasize individuals where as Chinese and other Asians stress relations and contexts. To generalize even further people in Western countries tend to value rights and privacy and are likely overvalue their skills and their importance in a group while people in Asian societies tend to value collective action, duty and harmony and tend to understate their skills and downplay their contributions to the group.

When an American is shown a fish tank full of fish he more often than not they describe the biggest fish. When a Chinese or Asian person is shown the same tank he usually describes the context in which the fish swim.

When an American is shown a picture of a chicken, cow and hay and told put together he usually picks the cow and chicken as both are animals. When a Chinese or Asian person is asked to do the same task he usually picks the cow and the hay, since the cow need the hay to survive, thus stressing the relational aspects of the picture. The conclusion here is that Americans tend to categorize things will Asians stress relationships.

There are a number of theories that attempt to explain these difference, Some say that Western values have their roots in ancient Greek Philosophy with its emphasis on individualism, reasoning and self discovery, ideas that were built up in Renaissance and Enlightenment. They then go onto say that Asian values have their roots in Confucianism, which emphasizes harmony and propriety, and this in turn is rooted in a kind of tribalism. Some have suggested that collective societies are most likely to spring up in hot areas with a lot if disease as means shunning outsiders who might bring in disease.

Most societies are collective in nature. There are few individualist ones. Some studies seem to indicate that individual choice is an illusion, rational choices are made taking into consideration of subconscious and social influences and that collectiveness is most in tune with human nature. Many would ague that relationships are a key to happiness. People with the most friends and social networks find success in their lives while people who have few social bonds are more likely to be depressed or contemplate suicide.

On changes in attitudes among Chinese athletes one American Beijing resident told the Washington Post, “Here in China we care about the nation. In America you care about just the individual. This is changing, the young people care about the individual here now. They just want to play for themselves. For the older people they just want to play for the nation.”

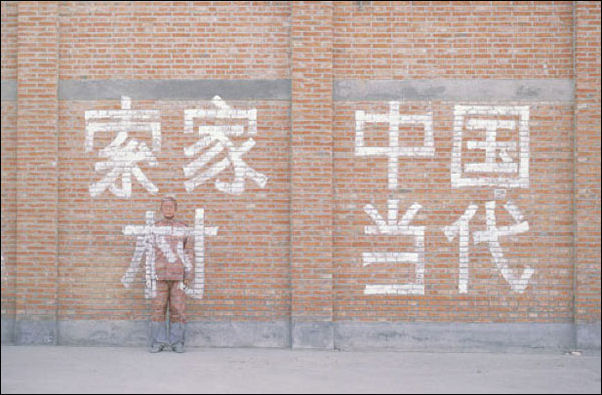

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

and what its like to be one in 1.3 bilion

Lack of Trust in China

Traditional bonds of trust and keeping one’s word have been weakened in recent years. Lawyers don’t trust their clients who often slip out without paying their bills. Nor do they trust judges who often make their decisions based on politics rather than the merits of the case. Job applicant lie to potential employers. Clients rip off their customers. Husbands have affairs. Friends cheat friends and uncles steal money from their nephews. [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, December 2006]

Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Rules aren’t clear and must be navigated on the fly. The food supply is full of life-threatening fakes. Factories spew chemicals into the air and water at alarming rates. Power and connections far outweigh justice, and social tension is growing.”

One Chinese lawyer told the Los Angeles Times, “Living in such a society is tiring for everyone. You’re forced to be vigilant so you don’t fall into pits, which are everywhere. Everybody is a victim and at the same time is an offender.” A Chinese sociologist said “Mistrust in China is less a problem of individual morality than the system. Even someone so moral he'd jump into the water to save a drowning person might still cheat to survive."

Reasons for the lack of trust include 1) the Cultural Revolution and other social and political upheavals that undermined traditional Confucian bonds, relationships and moral codes; 2) the immaturity of the market economy and its emphasis on making money above all else; and 3) the lack of religion and a fair justice system.

The transformation to a market economy has made China a very competitive place with people doing anything the can to get an edge. If one has connections however one can easily skirt the rules or even arrogantly ignore them. If one lacks connections or is otherwise powerless they can easily be trampled on by those with power and connections.

"Lying Flat"

In the early 2020s, a relatively small but visible group of Chinese urban professionals began drawing attention by choosing to "lie flat" ("tangping") and reject grueling careers to pursue what they called a "low-desire life." “"Only by lying down can humans become the measure of all things, " argued the "lying flat" manifesto. Cheryl Teh wrote in Business Insider: “It's a mindset, a lifestyle, and a personal choice for some disillusioned Chinese youth who have given up on the rat race and are staging a quiet rebellion against the trials of 9-9-6 work culture (See Below). The idea of "lying flat" is widely acknowledged as a mass societal response to "neijuan" (or involution). "Neijuan" became a term commonly used to describe the hyper-competitive lifestyle in China, where life is likened to a zero-sum game. [Source: Cheryl Teh, Business Insider, June 8, 2021 ==]

He Huifeng and Tracy Qu wrote in the South China Morning Post: “The movement’s roots can be traced back to an obscure internet post called “lying flat is justice”, in which a user called Kind-Hearted Traveller combined references to Greek philosophers with his experience living on 200 yuan (US$31) a month, two meals a day and not working for two years. “I can just sleep in my barrel enjoying a sunbath like Diogenes, or live in a cave like Heraclitus and think about ‘Logos’, ” the person wrote. “Since there has never really been a trend of thought that exalts human subjectivity in this land, I can create it for myself. Lying down is my wise man movement.” According to the anonymous poster, this humble existence left them physically healthy and mentally free. [Source: He Huifeng and Tracy Qu, South China Morning Post, June 9, 2021]

“Elaine Tang, who works for a Guangzhou-based tech firm, said the term was resonating with young Chinese who saw the odds stacked against them. “In recent years, property prices have skyrocketed, and the gap between social classes has become wider and wider, ” said the 35 year old, who has been married seven years but not yet had children. “The rich and the authorities monopolise most of the resources, and more and more working class like us have to work from 9am to 9pm, six days a week, but still can’t afford a down payment [on a flat] or even the cost of having a child.” A survey by Chinese microblogging site Weibo, conducted between May 28 and June 3, 2021 found 61 per cent of the 241, 000 participants said they want to embrace the lying flat attitude.

Tiny Times: A Reflection of How Materialist Chinese Society Has Become?

The “Tiny Times” series was a very successful group of relatively low-budget films that seemed to tap into a particular chord that nobody anticipated was so strong or so large. The first of the series, “Tiny Times”, released in June 2013, movie brought in $77.6 million and was the 9th biggest box office earner in China in 2013. Altogether there were four Tiny Times films. “Tiny Times 2” was released about six weeks after “Tiny Times”, “Tiny Times 3" appeared in July 2014, “Tiny Times 4" in July 2015.

Ying Zhu and Frances Hisgen wrote in China File: “The film follows four college girls as they navigate romance and their professional aspirations, but the bulk of the film is about the female longing for a life of luxury in the company of a good-looking man. “Tiny Times” is not a women’s film, though it does feature female characters, draped from head to toe in designer clothes and easily mesmerized by the presence of supposedly visually stunning males — not the usual, muscle-bound Hollywood types, but Asian boys of androgynous demeanor with compact frames, equisite facial contours and the look of perpetual youth. [Source:Ying Zhu, Frances Hisgen, ChinaFile, July 15, 2013]

“At first glance, Tiny Times might be mistaken for a Sinicized Sex and the City, but soon it becomes clear that the four boy-crazed, mall-loitering characters in Shanghai have little in common with the fiercely independent career women in Candace Bushnell’s New York. Positioned in the market by Le Vision Pictures of Beijing as a coming of age story, the rite of passage for one dazed girl in the film is to grow into a competent personal assistant to her oh-so-handsome male boss whose aloof demeanor and penetrating gaze constantly destabilizes her. Another girl from a nouveau riche family, showers her boyfriend with expensive clothes and accessories. The third girl — chubby, suffering from stereotypically low self-esteem and emotional eating — is made fun of throughout the movie as she obsesses over young tennis player, the one man in the movie who actually possesses something resembling muscle. The fourth girl, a budding fashion designer from a humble background, is trapped in an abusive relationship with yet another good-looking boy.

“Taking a page from the book of popular East Asian “idol dramas” that cater primarily to youth in their teens and twenties, the film features popular singers, actors, and actresses, cast regardless of any actual acting ability. Good idol dramas frequently feature teen romance, in which brooding characters with dark secrets and painful pasts elicit pathos and real emotion. Tiny Times, however, has done away with complex story arcs and character development. The film looks great but ultimately lacks substance.

“The four characters’ professional aspirations amount to serving men with competence. The film is a Chinese version of “chick flick” minus the emotional engagement and relationship-based social realism that typically are associated with the Hollywood genre. The only enduring relationship in Tiny Times is the chicks’ relationship with material goods. The hyper-materialist life portrayed carries little plot but serves as a setting for consumption, and is more akin to MTV or reality TV than real drama. With its scandalously cartoonish characters, the film would have worked better as a satirical comedy, except that the director is too sincere in his celebration of material abundance to display any sense of irony.

“We were caught completely off guard, stupefied by the film’s unabashed flaunting of wealth, glamor, and male power passed off as “what women want.” Its vulgar and utter lack of self-awareness is astonishing, but perhaps not too surprising. It appears to be the product of full-blown materialism in modern, urban Chinese society. The film speaks to the male fantasy of a world of female yearnings, which revolve around men and the goods men are best equipped to deliver, whether materially or bodily. It betrays a twisted male narcissism and a male desire for patriarchal power and control over female bodies and emotions misconstrued as female longing.

“Much to our horror and dark amusement Tiny Times’ male director Guo Jingming, won the award for “best new director” at the recently concluded Shanghai International Film Festival. A film school dropout turned popular fiction writer, Guo aspires to be an author of contemporary Shanghai. “Guo claims to represent the post 1990s “me generation” and has apparently hit a home run with the youth audience. According to the latest statistics from the China Film Distribution and Exhibition Association, the average age of a moviegoer in China has dropped to 21.2 years in 2012 from from 25.7 years in 2009. Tiny Times’s owes its success partly to a marketing campaign that relied heavily on social media networks reaching tens of millions of students.

“It comes as a consolation to us that the film averaged low ratings of 3.4 and 5.0 out of 10 on China's two most-visited online movie portals, mtime.com and douban.com. It was also hated by the critics, who condemned its "unconditional indolence," "materialism," and "hedonism" (People's Daily); "shallow approach, inexplicable storyline, childish characters and lavish lifestyles" (Beijing Review); "pathological greed" (Beijing News); "unabashed flaunting of wealth, glamour and male power," and "twisted male narcissism" (ChinaFile, carried also by Atlantic Online). A Guangdong Daily critic, borrowing a line from Eileen Chang, delivered the most damning review of all: "The whole film is just like 'a luxuriant gown covered with lice.'" [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin, October 12, 2013]

See Separate Article CHINESE YOUTH AND "LYING FLAT" factsanddetails.com

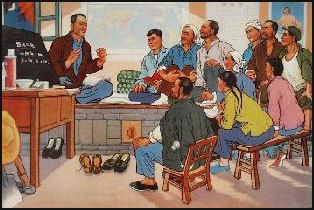

Image Sources: 1) Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 2) Cinfucius images, Brooklyn College; 3) Street scene, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021