POOR PEOPLE IN CHINA

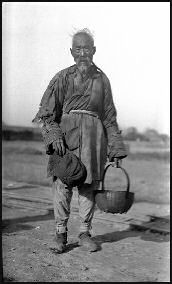

Beggar in the 1930s

Percentage of China's population living in poverty: A) Under $1.90 per day: 0.3 percent; B) Under $3.20 per day: 0.7 percent; C) under $5.50 per day: 3.7 percent. A) extreme, or absolute, poverty, is defined by the World Bank as a household that gets by on less than $1.90 a day, not enough to support the basic needs of survival; B) moderate poverty, defined as living on $1.90 to $3.20 a day, is where basic needs are met but just barely; and C) Relative poverty is defined by income below a certain level of the national average. In the case here this is between $3.20 and $5.50 per day. Most poor are in the countryside. [Source: World Bank, Wikipedia Wikipedia ]

Poverty is particularly concentrated in mostly rural provinces such as Guizhou, Tibet, Yunnan, Guangxi, Gansu and Ningxia. At the end of 2017, 2.8 million people in Guizhou lived below the poverty line, accounting for one-ninth of China’s population living in poverty.“Most of the population living in poverty is distributed in the mountain areas, ” Wu Qiang, deputy governor of Guizhou province, said, adding that the area is severely affected by limestone erosion. [Source: Li You, Sixth Tone, July 10, 2018]

China defines extreme rural poverty as annual per capita income of less than 4,000 yuan ($620), or about $1.70 a day, compared to $1.90 a day the World Bank benchmark. Up until the 2010s, China is defined poverty as having an annual income of below 3,000 yuan (US$450) a year. Li Guoxiang, a rural development researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said large sections of China’s population remain relatively poor even though the Chinese government says they have emerged from poverty. “It seems to be a game of figures, ” Li told the South China Morning Post, adding that there were“more realistic” metrics to measure “whether people have really been withdrawn from poverty”. The researcher defined this as people not having to worry about paying for the basics such as clothing, food, education, medical care and housing. [Source: Mimi Lau,South China Morning Post, November 2, 2017, New York Times, 2020]

Some see market potential of China’s lowest income brackets. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: Consumer products firms, for instance, do very well selling shiny little single-use foil packs of shampoos or face creams in China. These ‘affordable luxuries’ have become popular gifts among China’s poorest when they want to offer each other a special-occasion alternative to hand-made lye soaps. Similarly, banks wanting to offer Rmb savings services have gotten a foot in the door offering low-cost ways for floating population migrants in the cities to safely transfer funds to their families back home. Pharmaceutical firms have gotten permits to sell higher-end medications in China’s boomtowns only after agreeing to sell more basic or near-generic products at-cost in the countryside. Similar examples abound. Even China’s poorest seek to be part of the new economy, and to bring its advantages to themselves and their families. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

See Separate Articles: RURAL POOR IN CHINA AND PROBLEMS IN CHINESE VILLAGES factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SOCIETY AND COMMUNISM factsanddetails.com ; INCOME DISPARITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SUICIDES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RURAL LIFE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; VILLAGES IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINAFactsanddetails.com/China

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article on Poverty in China Wikipedia ; Social Issues in China peopledaily.com ; Wikipedia article on Social Issues in China Wikipedia ; Suicide in China Guardian story guardian.co.uk ; China Daily article chinadaily.com ; Center for Disease Control cdc.gov

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Rural Poverty, Growth, and Inequality in China by Yangyang Shen Amazon.com; “The Specter of "the People": Urban Poverty in Northeast China” by Mun Young Cho Amazon.com; “How China Escaped the Poverty Trap” by Yuen Yuen Ang, Catherine Ho, et al Amazon.com; “Income Disparity in China: Crisis Within Economic Miracle” by Dianqing Xu and Xin Li Amazon.com; “Sharing Rising Incomes: Disparities in China” by The World Bank Amazon.com; “Social Inequality in China”by Yaojun Li Amazon.com;

Poverty in China in the 2000s

In the mid 2000s, poverty was worse than it is now. About 13 percent of China’s population — about 200 million people — lived on less than $1 a day and about 40 percent of China’s population — about 560 million people — lived on less than $2 a day. In 2007, the 21 million poorest people in China lived on less than $88 a year. That year about 9 percent of the population of China lived in absolute poverty, compared to 15 percent in the Philippines and 50 percent in Vietnam. Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University described the extreme poor as people who “are chronically hungry, unable to get health care, lack safe drinking water and sanitation, cannot afford education for their children and perhaps lack rudimentary shelter — a roof to keep rain out of the hut — and basic articles of clothing, like shoes.”

Among the legions of poor are pensioners, unemployed workers in old industrial cities, construction workers, and skinny laborers who carry 40 bricks at a time that weigh 50 kilograms. Most are farmers who don’t earn much from selling their crops. In the 2000s, Newsweek described a girl who sold her blood to Beijing clinic so her family could buy fertilizer. Some of the worst poverty at that time affected children. Yyou could find children in textile and garment factories working 14 hours a day, seven days a week, sleeping by their machines. Boys in Green Mountain City were paid about 18 cents a load for carrying 20 kilogram of coal up a mountain. In the 1990s things were worse. School teacher often were only paid $50 a month and had to save for two years to be able to afford a bicycle. Even today, married couples often live apart, sometimes in opposite corners of the country, working at different places, to earn enough money to survive. They only time they get to see each other is during holidays, three weeks a year.

Rural Poverty in China

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: ““China has for decades treated rural people as second-class citizens, limiting their access to high-quality health care, education and other benefits under the strict Mao-era household registration system by keeping them from moving to the cities. More than 40 percent of the population — about 600 million people — lived on less than $5 a day last year, according to government statistics. Many people on low incomes say they are arbitrarily excluded from government aid despite living in difficult circumstances. “They could easily fall into poverty and face various deprivations, ” said Gao Qin, a Columbia University professor who studies China’s social welfare system. [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, October 26, 2020]

Reporting from Luotuowan, a poor village about 300 kilometers from Beijing, Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, “The average per capita income here, about $160 a year, is less than half the official threshold for poverty, and it is a tiny fraction of the average urban income of slightly less than $4,000. Most young people have long since fled for jobs in distant cities. The challenge to lift up impoverished backwaters like Luotuowan is a daunting one for the Communist Party. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 26, 2013]

In China’s rural hinterland, where 40 percent of China's 1.4 billion people live, incomes are, on average, less than a third of those in cities. In Guizhou, one of China's poorest provinces, you can still find peasant families that sleep in open-air huts, collect water in the mountains with shoulder poles, sleep under thin quilts in the winter and subsist off cornmeal gruel. The New York Times described one man who spent two years of income for electricity — two 60-watts bulbs that lit up his house for a few hours a night. The man said, "we don't have money to buy fertilizer, I don’t have a cow or ox to cultivate the land and the soil is barren."

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “To understand just how poor rural Guizhou is, you can look at the statistics. Or you can look at the children in Qixin village. Zhao Ai is nine, but is so short he appears three years younger. He eats nothing between leaving home at 6.30am — for a two-hour trek down the mountain to Ruiyuan primary school — and returning at 5pm. At Zhao's primary, the big educational challenge is "no food", says headteacher Xu Zuhua. Malnutrition stunts her pupils' growth and hampers their concentration. "Even though we are developing, it feels like urban areas are running while we are strolling," says Zhou Liude, who oversees Ruiyuan and nearby schools. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, October 2, 2011]

"The government has sought to invest in rural areas, and the benefits of growth are spreading. In the towns around Qixin you see stores with gleaming yellow motorbikes and adverts for 3G and coffee. But these remain unimaginable luxuries for families like Zhao's, who survive on basic farming and wages sent home by relatives working in cities. Their poverty is disguised by development: the further away from the road people live, the poorer they are — and the worse their children's grades — says Ruiyuan's headteacher.

The people in the countryside who have failed to profit from the economic reforms are perhaps the one who look back on the Mao years with the most nostalgia. Dissident Liu Binyan wrote in Newsweek, "they feel that though life was hard in those years, it was more or less egalitarian, and people had the right to, moreover, to stop the wrongdoing of bureaucrats. The peasants have been suffering under increasing financial burdens, sometimes including extortion at the hands of local officials. Corruption and abuse of power have run wild."

See Separate Article RURAL POOR IN CHINA AND PROBLEMS IN CHINESE VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

China Raises Rural Poverty Line

In November 2011, Associated Press reported: “China has redefined the level at which people in rural areas are considered poor by raising the official poverty line, despite a booming economy. A sharp upward revision in the official poverty line, announced by the government on means that 128 million Chinese in rural areas now qualify as poor, 100 million more than under the previous standard. [Source: Associated Press, November 30, 2011]

The new threshold of about $1 a day is nearly double the previous amount. While the revised poverty line is still below the World Bank threshold of $1.25 a day, the change brings China closer to international norms and better reflects the country's overall higher standards of living after three decades of buoyant growth.

The old limit, first set in the 1990s and increased periodically thereafter, focused on the bedrock poor at a time China was still largely rural and impoverished. As the country has climbed toward middle income status, experts from the World Bank and Chinese think tanks have urged the government to raise the threshold to capture more poor Chinese.

"The previous poverty line underestimated the number of poor people in rural China," the official newspaper China Daily quoted Wang Sangui, a rural development expert at Renmin University, as saying. "Only 2.8 percent of the rural population was officially considered poor, which was lower than in many developed countries such as the United States, which has a poverty rate of about 15 percent." With the higher threshold, more people qualify for government assistance. Funding for poverty relief is also being raised more than 20 percent this year to 27 billion yuan ($4.2 billion), the China Daily reported.

Homes of the Poor in China

House of the poor in the 1930s

Poor rural families often live in bamboo frame houses or mud-and-straw bricks homes with packed earth floors. Thatch-roof mud-wall houses found in some parts of Sichuan, Hunan and Yunnan provinces look like African huts. Houses with more than two story are rare. Progress and wealth means a family can move out of their mud and stone hut into a concrete house.

A typical rural family of nine in Yunnan Province with a per annual capita income of $364 lives in 600-square-foot house with a living room, 3 bedrooms, kitchen and 5 storage rooms. Peasant houses often have dirt floors, and little furniture other than a table, chairs and makeshift beds. A blackened shed serves as a kitchen. Many have color or black and white televisions.

Describing a mud brick home on the edge of the Gobi desert in poor Gansu province, Sheryl Wudunn wrote in the New York Times Magazine: "The shack had two rooms, each dominated by a kang...The dirt floor was swept clean and the furniture consisted of three rickety wooden chairs set around a crude wooden table, the mud walls were papered with newspapers, with pictures from old calendars providing a bit of color."

See Minorities.

Death of a 24-Year-Old, 20-Kilogram Woman — Sparks Outrage on China’s Poverty

Tiffany May wrote in the New York Times: To save money for her brother’s medical bills, the woman in a Chinese village often ate only rice and chili peppers or plain steamed buns. Years later, malnutrition wasted her body and worsened a heart problem — and she turned to the internet for help. “The woman, Wu Huayan, was a 24-year-old college student, but she weighed about 40 pounds and stood at a mere 4 feet and 5 inches, according to state news reports. She became an instant symbol of the harsh effects of poverty and hunger, and set off an outpouring of $140,000 in donations — a significant amount in rural China. Then, Ms. Wu died in a hospital — and public sympathy quickly turned to grief and outrage. [Source: Tiffany May New York Times, January 15, 2020]

“Ms. Wu died of heart and kidney diseases on according to an announcement posted by the school she attended, Guizhou Forerunner College. That was three months after she started her crowdfunding appeal. The images of her frail, stunted body touched off a torrent of criticism that officials had failed to help the disadvantaged at a time when China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has vowed to eliminate extreme poverty. For many Chinese, Ms. Wu’s plight was a stark reminder that despite the party’s pledges and the leaps the country has made economically, poverty was still a harsh reality in parts of rural China. Some also drew a link between the tragedy and the country’s problem with official graft that eats up public resources. “How much money do corrupt officials have to embezzle before they get caught? Hasn’t this already damaged our country and our people?” Yu Fannuo, a tech commentator, wrote on a blog. “Why is it that Wu Huayan, the girl in Guizhou weighing 43 pounds, was only discovered and helped when she was on the brink of death?”

“Ms. Wu’s death also cast a spotlight on the widespread public skepticism and distrust of philanthropy, which is a nascent concept in China. Questions arose over how several charities handled the money that had flooded in to pay for the woman’s hospital treatment, and why only a tenth of the funds was used. In a commentary, People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of the ruling Communist Party, asked if the charities had exploited a tragedy for commercial gain. “At what scale is phony fund-raising and tragedy consumption happening?” the paper said. [Source: Tiffany May New York Times, January 15, 2020]

“A few charities also helped to raise money, including the China Charities Aid Foundation for Children, a private organization that is overseen by the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The charity started a crowdfunding campaign that raised nearly $30,000 for Ms. Wu. It said it wired about $3,000 of that amount to her hospital in November. Under pressure to account for the rest of the money, the foundation said in statements that swelling in her organs had prevented Ms. Wu from undergoing surgery, and that Ms. Wu’s family had requested that the money be used for the operation and her recovery. The foundation acknowledged the public criticism of how it handled the donations and said it was investigating the matter.

Life of the 20-Kilogram Woman in Guizhou

Tiffany May wrote in the New York Times: “Ms. Wu grew up in a village in the poor, heavily rural province of Guizhou, state media reported. She subsisted for several years on a meager diet to help care for her younger brother. The malnutrition caused her to lose her eyebrows and some of her hair, and made her untreated illnesses worse. She began to have trouble breathing in 2018, and was admitted to a hospital in October 2020 for heart and kidney problems. [Source: Tiffany May New York Times, January 15, 2020]

“That month, she started an appeal on Shuidichou, an online crowdfunding site, saying that medical costs that would add up to nearly $30,000 were far beyond her means. Family and friends had already made loans and she was desperate, she said. “I’m only asking for help because I have no other way out, ” she wrote. “I still want to live a proper life. I still want to contribute to society and will use all my strength to fight my illness.”

“Her story was first reported by China Youth Daily late September and then widely circulated on social media. Ms. Wu said after that in a video interview with a local news outlet that she had received 100 calls and messages. Speaking in a soft voice from a hospital bed and wearing fuzzy blue pajamas, she thanked her donors, saying that the support made her feel less alone. “I feel as though I can suddenly see the sun again after being abandoned in the dark night, ” she said. “I don’t know your name, where you are and what lives you are living, and I haven’t appeared in your lives before — but I want to thank you for your sacrifices for an ordinary stranger like me.”

“In a video interview filmed in November by The Cover, a state-run outlet, Ms. Wu said that claims that she routinely subsisted only 30 cents day were blown out of proportion. She said that she always spent as little as possible on food, but that her village looked out for her and that a teacher had paid her school tuition without telling her.

Poverty in Rural China, a Lifestyle, Not a Choice

Deng Chaochao wrote in Sixth Tone: Working with the nation’s most destitute people has proven to me that the poor need more than just money to live with dignity. The village of Mendai is located in an impoverished part of western Hunan, a province in central China. Difficult to reach and suffering from a shortage of farmland and labor, it is also where I’ve spent the past year working on poverty alleviation programs. Early this year, a group of university students visited the village as part of their research work. One of them remarked that the villagers were not poor at all. After all, this student said, they had televisions, telephones, rice cookers, and cooking oil — what else could they need? At first, I didn’t know how to respond, since I had once felt the same way. I used to believe poverty was a matter of material limitations, and that lifting people out of poverty simply meant giving them enough money to buy the things they lacked [Source: Deng Chaochao , Sixth Tone, October 9, 2017. Deng is an expert in poverty alleviation at Serve for China, an NGO].

“Only after arriving in the countryside did I realize that poverty is a lifestyle. It is a way of thinking, one that permeates every aspect of people’s lives. Sometimes, when villagers invite me over for a meal, I’ll lend a hand in the kitchen. Once, after plating a dish, I noticed some oil left over in the pan. As I went to wash it out, my host grabbed me by the hand. She showed me a nearby rice bowl, the inside of which was filled with blackened oil, old fried vegetables, and leftover gunk from the pan. “We can reuse it next time, ” she said.

“I wanted to tell her reusing oil like this was unhealthy, but I worried this would come off as elitist. I was reminded of all the times I had seen older residents walking around with holes in their shoes, or middle-aged women waking up at five in the morning to trek 10 kilometers on market day. It can be hard to watch, but even though you want to help, you feel powerless to do so. Buying someone a pair of shoes or a bus ticket to town doesn’t solve anything; all it does is draw attention to your status as an outsider.

“The best way to help people is to get them to the point where they no longer feel the need to agonize over a bit of oil left in a pot, or to where they can buy shoes or a bus ticket on their own. Underlying current efforts to alleviate poverty and increase incomes in China is the desire to offer locals better development opportunities so that they feel safe and secure.

“During a visit to impoverished Houlong Village in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in July, I learned that local residents had no land to cultivate and were utterly dependent on monthly welfare payments of 250 yuan ($38). The sum was just enough to survive, provided it was used thriftily. The villagers I interviewed all expressed a desire for more money and better lives, but when I asked them why they didn’t move to one of China’s large cities in search of work, they all shook their heads and said it was too far. “Some observers will say they were just making excuses for their own laziness. However, in my view, their reluctance stemmed from a fear of the unknown, and of taking risks. They would rather make do with 250 yuan than try something new. “Yet opportunities always involve uncertainty and risk. When we work with villagers, we must make every effort to assuage their fears of the unknown and convince them to put their faith in us. At the same time, we should push residents to share the risks involved among themselves. Poverty alleviation isn’t a matter of wishful thinking; it requires sustained and coordinated efforts.

Poverty in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “Hopeless poverty is the most prominent fact in the Chinese Empire, and the bearing of this fact upon the relations of the people to one another must be evident to the most careless observer. So many Chinese are never sufficiently nourished. People who have no visible means of support, or no means which are at all adequate, and who have no idea where their next meal is to come from.The result of the pressure for the means of subsistence, and of the habits which this pressure cultivates and fixes, even after the immediate demand is no longer urgent, is to bring life down to a hard materialistic basis, in which money and food are the prominent facts. Money and food are in fact the two foci of the Chinese ellipse, and it is about them as centres that the whole social life of the people revolves.” [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894. Smith (1845 -1932) was an American missionary who spent 54 years in China. In the 1920s, “Chinese Characteristics” was still the most widely read book on China among foreign residents there. He spent much of his time in Pangzhuang, a village in Shandong.]

The poor “suffer from conditions which differ widely from those in some other countries, such as Turkey, in the important particular that it is not the government which oppresses them. The land-tax is very moderate; and with rare exceptions, the officials do not appear to make any demands upon the mass of the people. In China most especially, the misery of the poor is their poverty, and the hopelessness of their condition is due to their inability to lift themselves out of it by their own shoe-straps. And if they cannot do it themselves, it will not be done at all, so that the great mass of those who are poor must remain so. Yet there are enough exceptions to explain the process by which great wealth is dissipated, as the proverb says, in three generations; but these exceptions form no considerable proportion of the whole number of cases. As a rule, the poor man in China has no chance to better himself.

“Those who are both very poor and very ignorant, as is the fate of millions, have indeed so narrow a horizon, that intellectual turbidity is compulsory. Their existence is merely that of a frog in a well, to which even the heavens appear only as a strip of darkness. Ten miles from their native place many such persons have never been, and have no conception of any conditions of life other than those by which they have always been surrounded. In many of them even the instinctive curiosity common to all the races, seems dormant or blighted. Many Chinese, who know that a foreigner has come to live within a mile from their homes, never think to inquire where he came from, who he is, or what he wants. They know how to struggle for an existence, and they know nothing else.

They are the ultimate outcome of the forces which produce what is in Western lands called a "practical man," whose life consists of two compartments, a stomach and a cash-bag. Such a man is the true positivist, for he cannot be made to comprehend anything which he does not see or hear, and of causes as such, he has no conception whatever. Life is to him a mere series of facts, mostly disagreeable facts, and as for anything beyond, he is at once an atheist, a polytheist, and an agnostic. An occasional prostration to he knows not what, or perhaps an offering of food to he knows not whom, suffices to satisfy the instinct of dependence, but whether even this instinct finds even this expression, will depend largely upon what is the custom of those about him. In him the physical element of the life of man has alone been nourished, to the utter exclusion of the psychical and the spiritual. The only method by which such beings can be rescued from their torpor is by a transfusion of a new life, which shall reveal to them the sublime truth uttered by the ancient patriarch, “There is a spirit in man," for only thus is it that “the inspiration of the Almighty giveth them understanding."

Beggars in 19th Century China

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: Beggars are “diffused with a fearful impartiality all over the Empire. They are the superficial evidence of the existence in Chinese society of a deep-seated disease. By what means the pauperism of China can be mitigated and in time abolished, cannot now be discussed, but it is a problem well worth the attention of any philanthropist and of any statesman.

“We have already referred to the donations to beggars, of whom one almost everywhere sees a swarm. This donation also is of the nature of an insurance. In the cities, the beggars are, as is well-known, organized into guilds of a very powerful sort, more powerful by far, than any with which they can have to contend, for the reason that the beggars have nothing to lose, and nothing to fear, in which respects they stand alone. The shopkeeper who should refuse a donation to a stalwart beggar, after the latter has waited for a reasonable length of time, and has besought with what the Geneva arbitrators styled “due diligence," would be liable to an invasion of a horde of famished wretches, who would render the existence even of a stolid Chinese, a burden, and who would utterly prevent the transaction of any business, until their continually rising demands should be met. Both the shopkeepers and the beggars understand this perfectly well, and it is for this reason that benevolences of this nature flow in a steady, be it a tiny rill.

“The same principle, with obvious modications, applies to the small donations to the incessant stream of refugees, to be seen so often in so many places. In all these cases it will be observed that the object in view is by no means the benefit of the person upon whom the “benevolence" terminates, but the extraction from the benefit conferred, of a return benefit for the giver.

Image Sources: Bucklin archives; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2021