CHINESE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

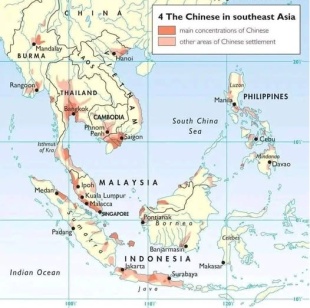

Large numbers of Chinese live in Southeast Asia. They are sometimes called "Asian Jews" because they started businesses, retained their customs and have become very rich. The economies in Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, and Thailand for the most part are controlled by rich Chinese Although some live in rural areas, the vast majority of Chinese in Southeast Asia live in urban areas. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The Chinese in Southeast Asia are also known as Huaqiao, Huaren, Sangley (in the Philippines), Tangren (Mandarin). They once referred to themselves as "Huaqiao" (Chinese sojourners) but now describe themselves as "Huaren" (Chinese people). The southern Chinese, who made up most of the of immigrants to Southeast Asia, also refer to themselves as "Tangren" (people of Tang), alluding ancestors that migrated to southern China at the fall of the Tang dynasty (A.D. 960–1279). Another common name for them is "Zhongguo ren" (people of the Central Kingdom). This term is avoided in Southeast Asia because it is sometimes perceived implying political allegiance to China. |~|

Overseas Chinese who live outside of China are citizens or permanent residents of the countries they live in not China. They are found in cities throughout Southeast Asia, often living together in Chinese communities or neighborhoods. Chinese in Southeast Asian cities have traditionally been involved in business, often as merchants or shop owners, with their places of business and residences grouped together in distinctive "Chinatowns." |~|

Companies controlled by ethnic Chinese are very powerful in all across Asia, with the exception of South Korea and Japan. The economic clout of the Chinese in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Southeast Asia would rank third or fourth in the world after the United States, Japan and possibly Germany.

See Separate Articles: OVERSEAS CHINESE: WENZHOU PEOPLE, SOUTH AFRICA, ITALY'S LITTLE CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE IN THE PHILIPPINES factsanddetails.com; HAKKA: THEIR HISTORY, MIGRATIONS AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; HAKKA LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE IN VIETNAM factsanddetails.com; BOAT PEOPLE: THE MOSTLY CHINESE VIETNAMESE WHO FLED VIETNAM AFTER THE VIETNAM WAR factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE IN SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com CHINESE IN THAILAND, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, CAMBODIA, VIETNAM See Below

Chinese in Southeast Asia Populations

Overseas Chinese workers in British Borneo

Chinese in Southeast Asia (percentage of population and date of the data): 9.3 million in Thailand (14 percent, 2015); 1) 2) 6.7 million in Malaysia in (22.4 percent, 2021); 3) Officially 2,832,510 in Indonesia (1.2 percent, 2010) (7 million in Indonesia of partial Chinese ancestry (3 percent); 4) 2.67 million in Singapore (76 percent, 2015), 2,675,521 (Chinese Singaporeans), not including 451,481 Chinese nationals); 5) 750,000 in Vietnam (less than one percent, 2019); 6) 1.15 million to 1.4 million in the Philippines (1.5 percent in 2013) and 27 million Mestizos and mixed; 7) 344,000 in Cambodia (2.2 percent, 2014); 8) 185,000 in Laos (1 percent, 2005) and 700,000 of partial Chinese ancestry. These numbers do not always reflect the true number of Chinese. Fully or partially assimilated Chinese are often not counted as Chinese. There are many levels and degrees of mixed blood. [Source: Wikipedia]

Chinese in Southeast Asia (percentage of population) in the 2000s: 1) 6 million in Malaysia (34 percent); 2) 6 million in Indonesia (3 percent); 3) 6 million in Thailand (14 percent); 4) 2 million in Singapore (76 percent); 5) 1 million in Vietnam (2 percent); 6) 600,000 in the Philippines (1 percent); 7) 300,000 in Cambodia (4 percent); 8) 25,000 in Laos (0.8 percent). These numbers do not always reflect the full extent of Chinese presence. Partially assimilated Chinese are often not counted as Chinese.

There are over 50 million overseas Chinese, with most of them living in Southeast Asia where about number around 29 million. Thailand is home of the largest population of Chinese outside mainland China and Taiwan. Malaysia is No. 2, followed by the U.S., with about 5 million Chinese (1.7 percent of the population, 2017). In the 1990s Chinese made up a majority of the population of Singapore (75 percent) and significant minority populations in Malaysia (22.4 percent), Thailand (14 percent) and Brunei (10 percent). [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ]

There is a also significant number of South Asians, mostly Indians or Pakistanis, living in Southeast Asia, particularly in Myanmar. Malaysia and Singapore. The majority were or are plantation labors although there are also a significant number or traders and merchants and professionals such as lawyers and doctors

Chinese Arrive in Southeast Asia

Chinese General in the Philippines from the Boxer Codex (1590)

The first Chinese to enter Southeast Asia were Buddhist monks, maritime traders and representatives of the Imperial Chinese government.. In ancient and medieval times, Chinese traders utilized Southeast Asian ports on maritime Silk Road but in the early days much of this trade was carried out by Arab mariners and merchants. Regular trading between China and Southeast Asia didn’t really begin in earnest until the 13th century. Chinese were attracted by trade opportunities in Malacca, Manila, Batavia (Jakarta) Some of the most detailed descriptions of Angkor Wat and other Southeast Asian civilizations came from Chinese travelers and monks. The Chinese eunuch explorer Zheng He (1371-1433) helped establish Chinese communities in parts of Java and the Malay Peninsula in part, many historians believe, to impose imperial Chinese control.

Beginning in the late-1700s, large numbers of Chinese — mostly from Guangdong and Fujian provinces and Hainan Island in southern China — began emigrating to Southeast Asia. Most were illiterate, landless peasants oppressed in their homelands and looking for opportunities abroad. The rich landowners and educated Mandarins stayed in China. Scholars attribute the mass exodus to population explosion in the coastal cities of Fujian and prosperity and contacts generated by foreign trade. Among the early places where Chinese went to work was the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1351-1767) in Thailand.

So many people left Fujian for Southeast Asia during the late 18th century and early 19th century that the Manchu court issued an imperial edict in 1718 recalling all Chinese to the mainland. A 1728 proclamation declared that anyone who didn't return and was captured would be executed.

Most of the Chinese who settled in Southeast Asia left China in the mid 19th century after a number treaty ports were opened in China with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, which ceded the island of Hong Kong to Britain and opened five treaty ports to British trade after the first Opium War. The ports made it easy to leave and with the British rather than imperial Chinese running things there were fewer obstacles preventing them from leaving. British ports in Southeast Asia, particularly Singapore, gave them destinations they could head to.

A particularly large number of Chinese left from the British treaty ports of Xiamen (Amoy) and Fuzhou (Foochow) in Fujian province. Many were encouraged to leave by colonial governments so they could provide cheap coolie labor in ports around the world, including those in colonial Southeast Asia. Many Chinese fled the coastal province of Fujian and Zhejiang after famines and floods in 1910 and later during World War II and the early days of Communist rule. Many of the legal and illegal immigrants from China continue to come from Fujian.

Chinese Advance in Southeast Asia

Of the Chinese who went abroad, some returned, some died under harsh working conditions but many stayed on were able to prosper under European colonial rule. Many of those who initially did well acted as middlemen between the Europeans and Southeast Asian producers and consumers.

The Chinese thrived under colonial rule. In French colonies laws discouraged participation in commerce by the native population but encouraged Chinese participation. In the British-controlled Malay states the Chinese managed the lucrative opium farms and controlled opium distribution. in Indonesia, the Chinese collected taxes and worked as labor contractors for the Dutch.

Over time, the Chinese became moneylenders, and controlled internal trade in the Southeast Asia countries where they lived. They also played various roles in the trade between Southeast Asian countries. Some accumulated great wealth and this encouraged other Chinese in China to follow in their footsteps.

Overseas Chinese worked as shop owners, traders, middlemen; became involved in wide variety of businesses; and founded family businesses and international firms. By the late 19th century they controlled much of the commerce in Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia and Indonesia and ran companies that businesses through the Asian-Pacific region.

Assimilation of Chinese in Southeast Asian Countries

Chinese that arrived before the mid 19th century often intermarried with local people and became assimilated into the local culture. As time went on they became progressively less assimilated. Early Chinese immigrants often created new identities that incorporated elements of both Chinese and local cultures. Examples include the mestizos of the Philippines, the Peranakans of Indonesia, and the Baba of Singapore and Malaysia. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Assimilation has been particularly difficult in Malaysia and Indonesia where Islamic practices discourage marriages involving Muslims and non-Muslims. For local people marrying a non-Muslim is also seen as rejection of Muslim-based nationalist pride.

Assimilation has been easier for Chinese in Thailand, where the people speak a tonal language somewhat related to Chinese, practice Buddhism and Chinese influences are present in the culture. Here more Chinese of have intermarried and become assimilated. Many have taken Thai names and speak the Thai language but retain Chinese cultural practices

In most countries in Southeast Asia Chinese children speak Chinese at home but use local languages at school and study government-designed curriculum that encourages nationalism and identification with the culture of the Southeast Asian nation where they live. Chinese culture is often transmitted outside the education system in community-based cultural and recreational clubs.

Despite all this there waves of anti-Chinese protests swept Southeast Asia in the 1950s and 1960s. See Chinese in Malaysia Below

Where Overseas Chinese in Southeast came from

Chinese Language in Southeast Asia

Overseas Chinese speak three main language groups: 1) Min (Northern and Southern), 2) Yue and 3) Hakka. Southern Min dialects include Hokkien and Fukien from Fujian; Chaochow, Teochew and Taechew from Chaozhou and Hainan. Northern Min dialects include Foochow and Hockchew from Fuzhou, Hungua from Xinghua and Hockchia. Yue dialects include Cantonese, Guangfu and Yueh. Hakka dialects include Hokka, Ke, Kechia, Kejia, Kek and Kheh. Technically these dialects are not really dialects. They are topolects (speeches from a particularly place). [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

It is not unusual for an overseas Chinese community to speak eight of more dialects. When this is the case one dialect becomes the lingua franca for the entire community. Hokkein, the Southern Min dialect of Fujian, is the primary dialect of many overseas Chinese communities in Malaysia, Singapore Indonesia, and the Philippines whereas Teochew, the Southern Min dialect of Chaozhou, is the primary dialect of the overseas Chinese communities in Thailand.

Even when different Chinese communities can not understand each other’s speech they can communicate through written Chinese, which more less universal for all Chinese dialects. See See WRITTEN CHINESE factsanddetails.com and HISTORY OF WRITING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Most Southeast Asian Chinese are required to learn local languages in schools and need skills in the local languages to get a top level education and land a good job. Southeast Asian Chinese keep up their Chinese because it use useful in business and helps them communicate with other Chinese in Southeast Asia, China and around the world

Society, Religion and Customs of Chinese in Southeast Asia

Thai Chinese astrrology chart

Customs regarding extended families, kinship, marriage, funerals, inheritance have remained the same or close to same as those practiced by Chinese in China. Descent is along patrilineal lines. Children are taught Confucian values of respect towards elders and filial duty. Women do most of the child rearing but sometimes grandparents help out so women can work. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ]

The religion observed by overseas Chinese is the generally the same mix of Taoism, Buddhism and folk beliefs practiced by Chinese in China. They perform rites to ancestors and celebrate Chinese lunar calendar festivals and visit temples. .In some cases their beliefs are stronger than Chinese in China because their religious beliefs were not discouraged by a Communist regime. |~|

Social stratification tends to be based on income levels in the country where the Chinese live rather than on class distinctions from back home. This is at least partly because most overseas Chinese are descendant of poor peasants. Social unification is based on bonds created by “dialect” groups, business associations, and shared surnames. Leaders tend to be selected in the basis of merit, connections and economic influence rather than family background. |~|

Overseas Chinese generally use the legal and political systems in their home countries to settle disputes and further their aims. In some cases they may turn to Tongs (secret societies) for some help. Tongs have their roots in 19th century fighting societies created when rival Chinese communities fought one another. They have traditionally been involved in “underground economies,” gambling and prostitution; often had their own “police force” of thugs and had links with Triads (organized crime groups). Tongs had forces of fighting men, and violent confrontation between rival secret societies was common, as was fighting between members of different subethnic groups (Cantonese against Hokkien, for example). |~|

The religious beliefs, family organization, social structures, holidays, festivals, funeral customs, forms of medicine and art of Overseas China and Chinese in Southeast Asia are in line with those of Chinese in traditional China. See the various categories under CHINA factsanddetails.com factsanddetails.com

Marriage and Family of Chinese in Southeast Asia

Marriages tend to follow the Chinese pattern. They are arranged or have a fair degree of parental input and couples tend live the groom’s parents after they get married. Overseas Chinese are more likely to marry a partner with different religious beliefs or from a different hometown area than Chinese in China. Intermarriage with local people varies from place and place and has traditionally been less likely in Muslim Malaysia and Indonesia than in non-Muslim countries. In the case of divorces local laws are generally stronger than Chinese customs. This means that divorces are often easier to get than they would be in China and women are more likely to get custody of the children. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Jean DeBernardi wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Urban Chinese generally marry in their twenties or thirties.It is common to marry across subethnic ("dialect") group boundaries; Overseas Chinese tend toward a high degree of religious tolerance, and religious differences are in general not a barrier to intermarriage. The extended patrilineal family persists, and at the most developed phase in the cycle a family may include parents, unmarried sons and daughters, and married sons with their wives and children. The nuclear family, however, is increasingly the norm, and young couples who can afford to do so establish independent residences. Child-rearing responsibilities fall primarily to the mother, though grandparents or other relatives sometimes tend children, freeing the mother to seek employment. |~|

Children are taught to respect their elders by using the appropriate terms of address and, ideally, to show deference to authority by not defending themselves when criticized. Education follows the standard of the country in which children reside: Chinese-medium education has been restricted throughout Southeast Asia (except in Singapore and in Malaysia, where the constraints are relatively moderate), and government-designed curriculums attempt to orient the younger generation toward identification with Southeast Asian national cultures. Chinese cultural forms are often transmitted outside the educational system by community-based cultural and recreational clubs.

Chinese Communities in Southeast Asia

Chinese in Southeast Asia tend to congregate in Chinese urban communities, There they have elaborately decorated temples, ancestor halls (“kongi”), dialect associations and Chinese chambers of commerce. Many Chinese live in two story houses that have a residence on the top floor and a business or shop on the first floor. Businesses of a similar kind are grouped together in the same neighborhood. Jewelers, for example, run shops in one area, while fabric sellers run shops in another area. Everywhere there are restaurants up and food hawker.

The Chinese often attend their own schools, read their own newspapers, attended their own operas and set up their own banks. They have community associations and try, whenever possible, to trade with each other. Chinese living outside of China have generally endured discrimination without complaining, partly out of fear that they would only make the situation worse if they rocked the boat.

Thai Chinese in Kanchanaburi

Many Chinese are members of societies within societies and have retained an intense loyalty "to family, village and clan." They are often more interested in events in China than the are in what was going on in the countries where they live. Descendants of Chinese who arrived abroad generations ago still send large amounts of money back home.

With the exception of Singapore and Malaysia, Chinese in Southeast Asia were required to adopt non-Chinese names as a means of forging an identification with the nations in which they live. Many surname groups have kongsi (clan organizations, whose members shared a common descent) that maintain genealogical records for that surname, though this tradition has declined somewhat. Using Chinese kinship terminology is a fundamental part of the Chinese identity for creolized Chinese such as the long-resident Baba community of Melaka Malaysia. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Economic Activity of Chinese in Southeast Asia

A fixture of many Chinese neighborhood in the shop-house,a common form of construction that combines a work place and residence connected and fronted by a 1.5 meter covered veranda.

Husband and wife often cooperate in running family businesses and children often assist in this work. Unmarried children also frequently help out in small family businesses. Some marriages have business interests in mind. People that marry into businesses are expected to help out and or at least be loyal. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

Businesses are often clustered together. For example, jewelers, fabric sellers, and sellers of religious items each occupied a section of a street or territory within the business district. Food has traditionally been hawked on street corner and Chinese restaurants served as places of entertainment and staging areas for weddings and festival banquets as well as places to eat and conduct business. An "underground economy"with illicit business activities, smuggled goods, opium, prostitution and illegal gambling had their niches where they operated.|~|

Overseas Chinese economic activity has traditionally focused on commerce, though they cane involved in variety of occupations. In the past most employees were Chinese but these days Chinese-managed firms are often multiethnic rather than exclusively Chinese. Overseas Chinese have historically been traders and middlemen in Southeast Asia. Chinese business networks are well-know for how far they reach internationally and often have, family, clan and ethnic components. |~|

Chinese-Style Business Practices

Chinese are known as risk takers. Their thinking sometimes goes that opportunities are rare and they must be pursued aggressively when they occur. Whole families will sometimes invest great sums of money on the chances of one member to get ahead. And, there is often an emphasis on getting rich while you can. Chinese businesses have been criticized for going after quick profits rather than looking out of the long term interest of their companies.Those that have become hugely successful have often done so by controlling supply chains in their business.

Malaysian Chinese merchants at a market

When starting a business Americans often go to the bank for a loan, Chinese go to friends and relatives, maybe getting the equivalent of $1,000 from one person, $2,000 from another person and maybe twenty thousand from a close relative. “We trust each other, so no interest. He know I do the same for him one day."

Many Chinese business owners like to run their companies on instinct and with total central control. They shun excessive meetings, don’t field questions, don’t provide explanations and don’t tolerate a lot debate. With a firm, centered hierarchy many Chinese feel that workers spend more time talking than working.

Chinese Family-Run Businesses

Family-run businesses are common and can be anything from a modest mom-and-pop shop, with children often providing labor, to multinational firms run by family members with overseas MBAs. In his book The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism, Gordon Redding wrote, "The Chinese family business...is peculiarly effective and a significant contributor to the list of causes of the East Asia miracle." Chinese-owned companies are often family run and have family members, other relatives or family friends in all the management positions. This contrasts with Western corporation which generally rely on professional managers. One Chinese businessman told the Washington Post, "We mostly hire people because he family knows them, or because they're introduced by a family member. That way you can find someone you can trust. Chinese find it not so easy to trust other people."

Many Chinese companies are run by old patriarchs backed up by Western-educated sons and daughters. The Chinese family system is much more effective in simple organizations like shipping, real estate and the production of low-market goods such as shoes and electronic but is not as effective in sophisticated organization that spend a lot on research and development and design high-tech products.

Confucian thought adapts itself very well to the hierarchical management style. One of the key components of a Chinese family-run business is trust. The Chinese have a reputation of distrusting people outside their clan or circle. The advantages of the Chinese family system of business are that it keeps management size down and allows quick decisions to be made without lengthy meetings, which in turn allows companies to move quickly into profitable markets. The disadvantages of the Chinese family system of business are that favoritism keeps talent out and family feuds can bitterly divide a company especially after a patriarch dies.

Modest Chinese businesses like noodle restaurants and small shops. are run by husband and wife teams, with children providing labor. Women often play an important role in organizing the finances. Explaining how such a business gets started one Asian businessman told Stanley Karnow in Smithsonian magazine: "Americans make big investment, hire manager, technicians.” Asians “cannot afford that, but wife and children all work hard. At first I keep old job while wife and friend take care of store; later I quit to run business full time. Until last year we are here seven days a week, sometimes until 2 in the morning. Now we are doing OK, so we take Sunday off."

There are critics of the the Chinese family business model. One Chinese businessmen said that many Chinese businessmen suffer from “Chinese restaurant syndrome” in that “they are contents with small-scale enterprises; they are happy to making a living. But Jewish people want to be the best and make a huge company.”

Overseas Chinese receiving deposed Vietnamese official

Views of Ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia Towards China

Michael Vatikiotis wrote in the International Herald Tribune: “Western social scientists have long postulated that ethnic Chinese communities in Asia have assimilated with their host societies and slowly lost their Chinese identity. But much of this research was conducted in the dark days of the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath, when links between ethnic Chinese and their motherland were cut off. [Source: Michael Vatikiotis, International Herald Tribune, August 24, 2005]

The trend for the last 25 years, since China opened up under Deng Xiaoping, has been for ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia to make return visits to China to explore their ancestral villages, network with distant relatives, relearn the language and - more recently - invest in China's booming economy. On a recent official visit to China, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra of Thailand made a pilgrimage to his grandparents' graves in Guangdong Province. Thailand's Charoen Pokphand Group was for many years one of the largest foreign investors in China.

China, for its part, has been careful not to claim the loyalty of its overseas kin. Successive prime ministers, from Zhou Enlai to Li Peng, made it clear that ethnic Chinese overseas owed their loyalty to host governments. This position has modified somewhat with the growth of China's economy. Special arrangements were made for ethnic Chinese returning to "invest in the motherland." A new network of "Confucius Centers" is being established to teach Chinese language and culture overseas. When anti-Chinese riots broke out in Indonesia a decade ago, Beijing felt compelled to lodge a protest with Jakarta. And China has increasingly made use of ethnic Chinese business and political contacts to further its influence in Southeast Asia.

All this raises the question of where the loyalties of ethnic Chinese overseas lie.The official line is that Singaporeans are culturally Chinese but politically Singaporean. It's this cultural identification that inspires pride in China's recent achievements and helps mute the kind of knee-jerk fear of China that tinges debates in the United States and Europe. "The idea and ideal of One China" are "deeply embedded in the Chinese mind," Singapore's foreign minister, George Yeo, said recently.

But as China extends its influence economically and politically, the nagging question is whether Beijing's policy of not claiming loyalty and affiliation will hold. With so much overseas Chinese capital now invested in China, how easy will it be for governments or individuals in Southeast Asia to resist calls for support and sympathy? The difference between being American and being Chinese is that America has a universal appeal, rather like a religion; being Chinese is a tribal thing, Yeo argues. "A Chinese cannot cease being a Chinese."

Chinese in Indonesia

Indonesian Chinese lining up for food in the 1960s

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: For much of Indonesia’s modern history, first under the dominance of the Dutch East India Co., then as a formal Dutch colony and, after 1949, as an independent nation, ethnic Chinese have rarely been able to live in peace. “No country harboring a Chinese minority possesses a blacker record of persecution and racial violence than Indonesia,” according to “Sons of the Yellow Emperor,” a study of overseas Chinese communities written by Lynn Pan, a leading authority on the subject. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012]

“A massacre triggered by economic unrest in 1740 left thousands of Chinese dead. Dutch authorities later barred Chinese Indonesians from traveling without special permits and introduced a system of racial classification that separated residents of Chinese descent from other groups. At the same time, they also gave Chinese economic privileges over other ethnic groups. Independence in 1949 brought a severe backlash, with the new government, led by a fiery nationalist, banning trade in rural areas by non-indigenous Indonesians and imposing other restrictions. [

“A failed communist coup in 1965 led to a spasm of horrific bloodletting targeted at ethnic Chinese and supposed supporters of the Indonesian Communist Party, or PKI, a revolutionary outfit that had been encouraged, funded and armed by Mao Zedong’s Communist regime in Beijing. Amid the chaos, a new regime took over in Jakarta, led by Suharto, who ruled Indonesia with an iron hand from 1965 until the mayhem of 1998. Discrimination against local Chinese became a pillar of Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime. After rejecting forced emigration as a solution to the “Chinese problem,” authorities opted for coerced assimilation, banning Chinese newspapers, schools, festivals and other expressions of identity different from that of the indigenous majority.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com ; DISCRIMINATION TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Chinese in Cambodia

There are an estimated 300,000 and 600,000 Chinese-Cambodians in Cambodia. They tend to be assimilated and many have intermarried with Khmers (one reason for variance in population numbers is how mixed blood and intermarried Chinese are counted) . They speak Khmer, worship at Khmer Buddhist temples and have Cambodian style weddings. Few can speak Chinese. In many cases the only thing they seems to have retained from their culture is the Chinese cakes served at special occasions and the custom of living with the wife’s family after marriage.

There are records of Chinese envoys visiting Angkor Wat in the 13th century. The Chinese have traditionally lived in the cities and towns and controlled businesses in part because the Khmers have traditionally looked down on commerce. Chinese have controlled much of the commerce in Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia and Indonesia since the 19th century and today are still involved in businesses throughout the Asian-Pacific region.

In the colonial period, with the help of French policies, Chinese were set themselves up so that about 400 of them dominated the Cambodian economy. In the 1960s there were about 500,000 Chinese in Cambodia. Most of them originally came from the southern Chinese province of Guangdong.

See Separate Article CHINESE IN CAMBODIA, LAOS AND MYANMAR factsanddetails.com

Chinese in Thailand

ornament on a Chinese temple in Thailand

Ethnic Chinese make up 10 to 14 percent of the population of Thailand, or around than 6 million to 9 million people (the range in numbers has to do with how mixed-blood Thai Chinese are counted). They are largely assimilated and many have intermarried with Thais. Many Chinese became Thai after a few generations. Many recognize their Chinese heritage but no longer identify with the Chinese ethnic group. An estimated 80 percent of Chinese Thais speak Thai at home. Thais intermarry with the Chinese more than the Malaysians do.

Teochew, the Southern Min dialect of Chaozhou, has traditionally been the primary dialect of the overseas Chinese communities in Thailand whereas Hokkein, the Southern Min dialect of Fujian, has traditionally been the primary dialect of many Overseas Chinese communities in Malaysia, Singapore Indonesia, and the Philippines.

Bangkok has a large, influential Chinese community. They are said to be fond of shopping and new condominiums. Bangkok supports six daily Mandarin-language newspapers. At one time half the population of Bangkok was at least part Chinese by descent. Even the royal family has some Chinese blood.

Assimilation has been easier for Chinese in Thailand — where the people speak a language somewhat related to Chinese, practice Buddhism and there are many Chinese influences in the culture — than elsewhere in Southeast Asia. In Thailand, many Chinese have taken Thai names.

See Separate Article CHINESE IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com

Chinese in Vietnam

There are about one million Chinese in Vietnam (two percent of the population). There used to be more but many were forced to leave. Many of the so-called Boat People that fled Vietnam during a much-publicized exodus between 1975 and 1980 were Chinese Vietnamese (See Boat People).

The Chinese did well in the colonial period. French laws discouraged participation in commerce by the native population but encouraged Chinese participation. In 1970, Chinese Vietnamese made up 5.3 percent of the population but controlled 70 to 80 percent of the commerce. After the Vietnam War, the Chinese were targets and many fled or were driven out.

At one time, assimilation was easy for Chinese in Vietnam, where people speak a language somewhat related to Chinese, practice some Buddhism, follow Confucianism, and have many Chinese influences in their culture. Many Chinese intermarried with Vietnamese, took Vietnamese names and spoke Vietnamese at home.

See Separate Article CHINESE IN VIETNAM, BOAT PEOPLE, OVERSEAS VIETNAMESE (VIET KIEU) AND VIETNAMESE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Chinese in Malaysia

Chinese Malaysian soup

There are around 6.7 million ethnic Chinese in Malaysia. They are mostly descendants of Chinese who arrived is various waves of immigration and established themselves in the cities. Like their counterparts in Singapore, Indonesian, Thailand and Vietnam, many are from the southern Chinese province of Fujian. Many of the Chinese in Malaysia were brought in by the British in the 19th century to work the tin mines and rubber plantations as laborers.

In the past, Malaysia was divided into the Chinese haves and Malay have nots. Ethnic tension ran high. A Chinese living in Malaysia I talked with compared the situation in his country to apartheid. Assimilation has been particularly difficult for Chinese in Malaysia and Indonesia where Islamic practices discourage marriages involving Muslims and non-Muslims. For local people marrying a non-Muslim is also seen as rejection of Muslim-based nationalist pride.

The Chinese have traditionally dominated business in Malaysia and run shops and hotels. Many are descendants of laborers who worked hard and saved so that succeeding generations could prosper. Many are self employed. In the 1970s, Kuala Lumpur about 90 percent of all the shops, banks and factories are were owned by Chinese and Chinese businessmen still control a large share of the commercial enterprises. These days “bumiputra” (Malay) billionaires run much of the economy rather Chinese billionaires.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com; MINORITIES, ETHNIC ISSUES, DISCRIMINATION AND GOVERNMENT POLICIES IN MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: East and Southeast Asia”, edited by Paul Hockings (C.K. Hall & Company); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025