PREJUDICE AND DISCRIMINATION AGAINST CHINESE

Chinese woman serves food to refugees in Surabaya in the 1940s

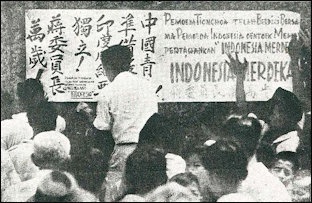

The Chinese in Indonesia have a long history of being harassed and discriminated against. The discrimination dates back centuries to the Dutch colonial era, when thousands were killed or forced into ghettos. Ethnic Chinese were also attacked in the Indonesian government's anti-communist purges of the mid-1960s. A small businessman told the New York Times in the 1990s, "We should send all the Chinese men back. The woman can stay and marry Indonesians, and then the Chinese race here will disappear...And if they convert to Islam, then they can stay because they will change. Because Chinese who convert do not act like Chinese. They are not arrogant and they do not swagger." A 36-year-old laborer in Surabay told the New York Times, "We should expel all the Chinese. If a politician said that, everybody would vote for him."

Indonesia has had some of the world's most racist laws and many of them have been directed at the Chinese. The Chinese language, names, traditions and schools have all been banned. Although Suharto did a great deal to help enrich a handful of Chinese cronies he also made Chinese-language books and newspapers, and the celebration of the Chinese New Year and even doing the lion dance, illegal. Confucianism was eliminated as a tolerated religion. Many of these laws were relaxed after Suharto was ousted.

The Chinese used to carry identity cards that identify them as Chinese. On these cards they were classified as non-pribumi (non-indigenous) and given special codes that police and the military could instantly recognize. All of their documents said "Chinese." In accordance with the 1858 citizenship law Indonesians of Chinese descent had to obtain a court document (SBKRI) as proof of citizenship even if they were born in Indonesia and their parents had proper documents. One Cornell-educated sociologist told Newsweek, "I'm 100 percent Indonesian. But when a cop or bureaucrat sees my face and my ID card, I'm immediately labeled as a Chinese." SBKRI stands for Surat Bukti Kewarganegaraan Republik Indonesia which means a certificate of Indonesian citizenship.

The Chinese were excluded from serving in the civil service, police, military or working at universities. There were unwritten quotas on the number of Chinese students that were admitted to universities. Many Chinese had no choice but to attend private schools or study abroad. This often worked in their favor as they got a better education than Indonesian students at state universities. In many towns, the Chinese were prohibited from setting up stalls in the local markets. There was some discussion of passing laws like those in Malaysia that gave non-Chinese businesses an advantage over Chinese ones. The discrimination explains why many Chinese have been reluctant to venture out of their exclusive business comfort zones.

Book: “Sons of the Yellow Emperor,” a study of overseas Chinese communities written by Lynn Pan, a leading authority on the subject.

See Separate Articles CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN VIOLENCE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

History of Discrimination Against the Chinese

Thomas Fuller wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “Tension involving overseas Chinese has been a recurring theme in Indonesia and throughout Southeast Asia, both before and after countries in the region became independent. Like Jews in Europe, the Chinese were often traders or financiers, and many, although far from all, achieved commercial success. During the days of Mao Zedong's rule in China, overseas Chinese were looked upon with suspicion in Indonesia and tens of thousands were killed in anti- Communist massacres of the 1960s. [Source: Thomas Fuller, International Herald Tribune, December 14, 2006]

The history of prejudice against the Chinese goes back a long time. The Dutch placed the Chinese is a special class, ""foreign Orientals," and used Chinese traders as middlemen between colonial authorities and indigenous people, which aroused resentment among the local people. The Chinese were forced to live in ghettos, were not allowed to own land and never assimilated into the indigenous population. In the early 20th century, Muslim groups sometimes directed their anti-colonial feelings towards the Chinese.

The Chinese encountered considerable hostility from both Indonesians and Europeans, largely because of the economic threat they seemed to pose. In 1740, for example, as many as 10,000 Chinese were massacred in Batavia, apparently with the complicity of the Dutch governor general.” Dutch authorities later barred Chinese Indonesians from traveling without special permits and introduced a system of racial classification that separated residents of Chinese descent from other groups. At the same time, they also gave Chinese economic privileges over other ethnic groups. Independence in 1949 brought a severe backlash, with the new government, led by a fiery nationalist, banning trade in rural areas by non-indigenous Indonesians and imposing other restrictions. [Source: /*\, Library of Congress *]

In the early independence era in the 1950s written Chinese and the teaching of Chinese in school were banned. Chinese who did not have citizenship were deported. Those that remained were given the choice of learning the Bahasa Indonesian or are being deported themselves. In the 1960s the Indonesian government again prohibited the Chinese from exercising free choice of residence, requiring them to live in cities and towns. In 1960, Sukarno issued a decree banning "aliens" (Chinese) from doing business in the countryside. It was aimed at the Chinese engaged in the rural retail trade, long dominated by the Chinese. Nearly 100,000 Chinese were forced to shut down their businesses and return to China. Those that remained moved to the cities, where many struck it rich.

According to the Jakarta Post: Chinese “were required to have an SBKRI, which was an official document proving their Indonesian citizenship, even if their great, great grandparents had been born, lived, died and were buried in Indonesia. Although some patriotic Chinese-Indonesians fought for an independent Indonesia along with youths from various “indigenous” ethnic groups, discrimination against them by both the state and other ethnic groups has remained. In 1959, president Sukarno, for instance, limited Chinese-Indonesian retail businesses to the regency and municipal levels in a measure to protect indigenous entrepreneurs. SBKRI was used to extort money from Chinese-Indonesians whenever they required official documents, such as passports and birth certificates. Even now, long after the policy has been scrapped, complaints about government officials extorting Chinese-Indonesians still persist. [Source: Jakarta Post, February 2 2011]

Discrimination Against the Chinese Under Suharto

Suharto treated Chinese-Indonesians more harshly than Sukarno due to suspicions that many supported communism in Indonesia in the 1960s. After Suharto came to power in 1965 he placed rigid restrictions on the Chinese designed to wipe out Chinese identity who chose to become Indonesian citizens. A 1967 presidential decree prohibited Chinese New Year celebrations and various Chinese arts were prohibited. Despite this some wealthy Chinese businessmen prospered in the Suharto years presumably because they developed schemes in which the Suharto family were given large slices of the pie.

refugees waiting in line for food in the 1940s

During the Suharto years, nearly all Chinese Indonesians obtained Indonesian citizenship, often at high cost and as a result of considerable government pressure. Popular resentment persisted toward Chinese economic success, however, and nurtured a perception of Chinese complicity in the Suharto regime’s corruption. In the 1980s came calls for Suharto to rein in numerous large Chinese business conglomerates that many argued controlled the economy.

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “Discrimination against local Chinese became a pillar of Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime. After rejecting forced emigration as a solution to the “Chinese problem,” authorities opted for coerced assimilation, banning Chinese newspapers, schools, festivals and other expressions of identity different from that of the indigenous majority. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012 /*]

“Under Suharto, everything Chinese was suppressed,” said Myra Sidharta, an 85-year-old, third-generation Chinese Indonesian who has chronicled the Chinese minority. Sidharta said that she sometimes played golf with Suharto before he seized power and that she found him “very boring” but not a frothing bigot. His anti-Chinese policies, she said, derived from a political calculation that the relatively well-off Chinese minority served as an easy and popular scapegoat. /*\

Violence Against Chinese

The Chinese are often the victims of violence. Tens of the thousands died in 1965 during the anti-Communist purges of 1965 that left between 300,000 and 1,000,000 Indonesians dead. Communists. Even so most of the dead were indigenous Indonesians. In December 1965, after a failed communist coup in September 1965, mobs were engaged in large-scale killings, most notably in Jawa Timur Province and on Bali, but also in parts of Sumatra. Members of Ansor, the Nahdatul Ulama's youth branch, were particularly zealous in carrying out a "holy war" against the PKI on the village level. Chinese were also targets of mob violence. Estimates of the number killed — both Chinese and others — vary widely, from a low of 78,000 to 2 million; probably somewhere around 300,000 is most likely. Whichever figure is true, the elimination of the PKI was the bloodiest event in postwar Southeast Asia until the Khmer Rouge established its regime in Cambodia a decade later. [Source: Library of Congress]

Anti-Chinese riots in Medan, Sumatra in 1994 left one man dead and alarmed Chinese businessman throughout Indonesia. An ethnic Chinese factory owner was pulled from his car and stoned and beaten death as he tried to protect his factory from thousands of laborers who protesting the mysterious death of a union activist. Thousands of looters with machetes and iron picks laid to a shopping mall owned by Chinese. Many Chinese n Indonesia saw this as an early warning and they began moving their assets to safer havens such as Singapore, and Australia.

In May 1998, riots broke out in which hundreds of Chinese stores were burned and Chinese women were raped and murdered. When many Chinese Indonesians fled the violence, the subsequent capital flight resulted in further economic hardship in a country already suffering a financial crisis. By 2005 many had returned, but the economic and social confidence of many Chinese in the country was badly shaken by the experience.

See Separate Article FALL OF SUKARNO, RISE OF SUHARTO AND THE MYSTERIOUS COUP OF 1965 factsanddetails.com

Violence Against the Chinese After the Asian Economic Crisis

man shot in the face in the 1940s

During the Asian economic crisis in 1997-1998 and through the period before and after Suharto’s resignation in May 1998 and the selection of a new president in June 1999, ethnic Chinese were the targets of violence all across Indonesia. Ethnic Chinese women and girls as young as 10 were raped during looting of Chinese neighborhoods by organized gangs. Some of the victims were gang raped in front of their parents and then set on fire and killed."Some of the attacker said, 'You must be red because you are Chinese and a non-Muslim," one woman told the New York Times and added that many women committed suicide afterwards rather than lose face.

Many of the riots were sparked by resentment towards the Chinese for their wealth. Because ethnic Chinese control so much of the Indonesian economy, many Indonesians blamed them for the crisis and took out their anger by looting Chinese-owned shops, shouting anti-Chinese slogans and attacking Chinese. The violence was often triggered by rumors and small things. One spate of violence began after a Chinese man complained about the noise made by drummers during a Muslim feast day.

In January 1998, people in eastern Java broke into Chinese-owned stores with crow bars and looted rice, cooking oil and other staples. The looters accused the Chinese of price gauging, although prices they charged were the same as those charged by Muslim merchants. One sympathizer told the Independent. "The Chinese are uptight and greedy. I support what happened, and it will happen again if the prices keep going up.”

In May 1998, the month that Suharto was ousted, “pro-democracy student demonstrations morphed into an orgy of rioting that hit Chinese-owned shops and homes with particular fury,” according to Washington Post. Much of the violence was not a spontaneous venting of revenge but a planned campaign of terror. Witnesses often reported that violence began when thugs, brought in by truck, began shouting anti-Chinese and pro-Muslim slogans like "Destroy the Chinese," "I love Muslims," and "Money hung Chinese fools," outside Chinese-owned businesses and encouraging local people to join them. One man told Time, "Everyone wanted to get in a kick or a cut; it was a badge of pride to have taken part.”

Victims of the May 1998 Anti-Chinese Violence

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In May 1998, during two deadly days of racially fueled mayhem, rioters killed 1,000 people and raped 87 women, most of Chinese descent. Others cowered in their homes as the rape squads, reportedly led by army thugs, roamed the streets of Jakarta, the Indonesian capital. Ruminah winces as she recalls the afternoon a mob ransacked her tiny hair salon, smashing windows and destroying both the business and her faith in justice in her homeland. The petite Ruminah goes by one name, lost more than her shop that day. Her developmentally disabled son was killed in a fire set by looters at a nearby mall. "I'm not a smart person," said Ruminah, an Indonesian-born Muslim whose grandmother married a Chinese merchant here, "but I know my son died that day because he looked Chinese." [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2010 /]

man being taken to hospital

“In Ruminah's lower-class street in East Jakarta, neighbors viewed her as Chinese, even though the mother of five has never truly identified with her Chinese roots. She can't speak Chinese and doesn't even know where in China to trace her roots. "They would ask the same question: 'Why do you live here among the poor? We know that all the Chinese are rich,' " Ruminah recalled. Local boys teased her 14-year-old son, Gunawan, but not because of his learning disability. "They harassed him because he looked Chinese," she said. "He would come home crying, and my husband would tell him to ignore the taunts. He said they were just words." /

“That changed during the 1998 Asian financial crisis, when mobs took to the streets and attacked ethnic Chinese they blamed for the economic downturn. Many analysts believe Suharto encouraged the violence to take the pressure off his government for the loss of jobs and rising prices. On the first night, Ruminah went looking for her son, who had gone to watch a fire at a local mall. Later, wearing a mask to guard against the stench, she inspected hundreds of corpses laid out in the parking lot outside the mall. She never found him. "I only have his burned clothes," she said, her voice breaking.” /

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “When mob violence swept across the Indonesian capital in May 1998, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, an ethnic Chinese geologist and businessman, joined terrified neighbors in the heavily Chinese district of Pluit to defend their lives and property. They used sticks, gasoline bombs and even a few old shotguns to fend off attackers drunk with anti-Chinese fury. The frenzy of looting, rape and murder — triggered by a deep economic crisis and a vicious struggle for political power — stirred comparisons to Nazi assaults against the Jews. It so traumatized Indonesians of Chinese descent that many fled abroad, despairing at the seemingly ineradicable racism of their home country. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18, 2012]

Descriptions of Attacks Against the Chinese

Describing an attack on Chinese in February 1998 in western Java, Ron Maroau wrote in Newsweek, "The first warning came in a phone call from school. Don't send your daughter today...Rumors were swirling...angry Muslims would attack Chinese-owned stores after noon prayers at a local mosque."

"Just before noon, a crowd of at least 20 angry young men began heaving rocks into the shop. Wielding knives, scythes and iron bars, they stormed inside, knocking over displays of rice, sugar, soybeans and cooking oil. They robbed the cash drawer, stole two tons of rice, started a fire...shouting "Kill the Chinese." The owner was chased down the street by an angry mob and found safety in a shop owned by a non-Chinese Indonesian friend.”

Describing violence against the Chinese in Sumatra in September 1998, David Liehold wrote in Time, "The trouble began with a rumor...word had got around that a Malay man had been killed by an ethnic Chinese following a minor traffic accident. Within hours mobs of armed men were rampaging through the streets, setting fire to mostly Chinese-owned houses and shops, By sunrise...more than 400 buildings had been damaged or destroyed, and the Chinese fled to neighboring towns.

Reaction By Chinese to the Violence

During the unrest around the time of Suharto’s resignation many Chinese fled their homes. Those that had enough money escaped to Australia, Singapore or Malaysia. Those that didn't went to neighboring towns. Around 200,000 Chinese Indonesians sought to establish residence outside of Indonesia. Almost 8,000 most wealthy ethnic Chinese from Indonesia quietly moved to Perth and other Australian cities. Chinese in Beijing and the Philippines demonstrated outside embassies in those countries over the treatment of ethnic Chinese in Indonesia.

Chinese in Indonesia stockpiled weapons, formed vigilante groups to protective neighborhoods, hired private security guards to protect their homes. Chinese shop owners paid soldiers to guard their property. Chinese tycoons drove around in huge four-wheel-drive vehicles with massive crash bars on the bumpers and ample space for body guards. Some wealthy Chinese gave out free food or sold food at cheap prices to earn good will of the people.

Chinese with dark skin had an easier time avoiding trouble because they blended in better with Indonesians. Some of the violence and rage among the global Chinese diaspora was stirred by photos that circulated on the Internet showing ethnic Chinese women purportedly being raped and murdered. Many of those photos proved to be hoaxes.

Lack of Justice After the Anti-Chinese Violence

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Many of the 5 million ethnic Chinese here, who represent a scant 2 percent of the population in this predominantly Muslim nation of 248 million, have for years awaited the results of a government investigation of the attacks. Twelve years later, no arrests have been made. The inquiry stalled years ago when investigators said they failed to find hard evidence of military involvement. The Indonesian government has recently suggested that it will no longer pursue the matter, despite lingering suspicions that the riots were instigated by soldiers influenced by the nation's political leadership. Without an official report to the contrary, many Indonesians question whether the rapes even occurred. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2010 /]

“Activists say there are new efforts at national healing. Prabowo Subianto, the former son-in-law of Suharto, met last summer with ethnic Chinese to publicly explain for the first time that he was not involved in the mayhem. "Many are still ambivalent about his story," said Jemma Purdey, a research fellow at the Center of Southeast Asian Studies at Monash University in Australia. "But if you meet someone and they tell you straight to your face they didn't have part in things, you have to respect that." In 2009, government officials also met with historians to draft language for Indonesian school textbooks acknowledging that the anti-ethnic Chinese bloodshed actually happened. "The scar from that violence remains," said Yentriyani, the commission leader. "How much Indonesians want to heal it, depends on who you talk to." /

Easing of the Anti-Chinese Laws in Indonesia

The Suharto government’s program of assimilation for the Chinese began to be phased out in 1998. Long- discouraged symbols of Chinese identity such as Chinese-language newspapers, schools, and public rituals, and the use of Chinese names, are no longer subject to strict regulation.

After the Suharto was ousted the bans on the Chinese language, names, traditions and schools were lifted. Chinese New year was made a national holiday in 2003 and Chinese were allowed do perform the lion dance and dragon dance in public once again. Chinese radio and television stations have popped up in places with large Chinese populations. In some of these places Indonesian leaders have even appeared in Chinese clothes.

Some of the rules that discriminated against Chinese remained in place into the 2000s. Indonesian Chinese were required to show a SBKRI document to acquire official documents in some places even though the practice was supposed to have ended. According to the Jakarta Post in 2008: “Every Indonesian born from a Chinese couple needs to produce a SBKRI when they are 18 years old.” [Source: Jakarta Post, October 19, 2008]

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “ But, as the country stabilized into a functioning democracy, the first elected president, the liberal-minded Muslim cleric Abdurrahman Wahid, and his successors introduced legal and social reforms aimed at undoing past discrimination. They lifted bans on expressions of Chinese culture, revised nationality rules and even declared Confucianism an official religion, alongside Islam, Hinduism, Catholicism, Protestantism and Buddhism. The Ministry of Religious Affairs now has a special unit dedicated to promoting and protecting an ancient Chinese system of Confucian ethics that China itself does not consider a religion. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012 /*]

Life for Chinese After the End of Suharto

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “Basuki, urged by friends and relatives to flee, decided to take a gamble and stay, judging that “the people who should leave are the rioters, not us. This is my country. Why should I leave?” Since then government bureaucrats have destroyed Basuki’s mining business, and, as a Christian, he has endured taunts that Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation, doesn’t need “infidel” interlopers.” [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18, 2012]

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “For ethnic Chinese, long viewed as scapegoats for Indonesia's economic woes, life after the 1998 riots has been bittersweet. On one hand, more Chinese Indonesians have run for public office and a number of discriminatory laws have been repealed. Yet many still feel like unwanted outsiders, their community cast as a greedy merchant class with allegiances to Indonesia and China. Without question, analysts say, there has been progress since the ouster of President Suharto, whose government required ethnic Chinese to adopt Indonesian names and banned Chinese characters and festivals. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2010 ]

“After the dictator was forced from office in 1998, the year of the riots that many believe he fomented, Indonesia has encouraged the spread of Chinese culture. "The lot of ethnic Chinese here has greatly improved since Suharto, but that doesn't mean the riots' underlying problems have been resolved," said Leo Suryadinata, a professor at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University who focuses on Chinese Indonesian issues. "Issues of poverty, ethnic tension and a gap between rich and poor that led to the violence are still very much alive."

Golden Age for Indonesian Chinese?

By the mid 2000s, a once-prohibited traditional Chinese dragon dance was part of Indonesian independence day celebrations.Thomas Fuller wrote in the International Herald Tribune, “It wasn't so long ago that Chinese writing was banned from public places here and Chinese schools and newspapers were prohibited. But walk into the former office of Suharto, the retired Indonesian strongman who maintained these laws in an attempt to integrate the ethnic Chinese community, and a large decorative poster of Chinese characters greets visitors. "In the old days I would have been arrested for this," Dino Patti Djalal, an adviser to the government and now the occupant of Suharto's office, said as he glanced back at his poster. Djalal, who is not Chinese, added: "This shows the progression of Indonesia. We now take multiculturalism as a given in life." After centuries of segregation, periodic violence and tension over their higher levels of wealth, Indonesia's Chinese community, is now enjoying what many are calling a golden era. "The situation of the Chinese has never been as good as today," said Benny Setiono, head of the Chinese Indonesian Association, a nonprofit group that represents the community. "We feel more free, more equal." [Source: Thomas Fuller, International Herald Tribune, December 14, 2006 +]

“In Glodok, a warren of warehouses not far from Jakarta's old port that was badly damaged during the 1998 riots, a consolidated peace now reigns. Chinese shop owners and their employees say they cannot recall any racial arguments breaking out in recent years. "I don't feel any tension," said Phie Ching Huat, who runs an electronics shop. Phie, whose Indonesian name is Sukino, said many ethnic Chinese families now send their children to schools that teach Chinese dialects, mainly Mandarin. With the rise of China as a world power, learning Chinese is becoming popular among Indonesians of all ethnicities. "You can hear Mandarin and Cantonese everywhere," said Phie, whose relatives' shop was burned in the riots. +\

“Indonesians said mentalities are also changing here, especially the notion that all Indonesian Chinese are rapaciously rich, a common perception during the Suharto years, when a select group of Chinese cronies controlled large, high-profile businesses. This is now all ancient history for some young people. "There are some very rich Chinese, but there are some very poor Chinese, too," said Sayidah Salim, a 20-year-old student at the Islamic State University, outside Jakarta. "If people want to work hard they will earn more money." +\

“Djalal, the government adviser, credited the Chinese government for changing attitudes in Indonesia about the Chinese minority here. "They are projecting a very friendly, benevolent face," he said of Beijing. Like many other countries in the region, Indonesia is wooing tourists from China. Setiono, of the Chinese Indonesian Association, said his organization was reaching out to poorer Indonesians of all ethnicities and providing food and medicines. Ethnic Chinese, he said, also need to be more mindful of the wealth gap and must work to reduce it if racial harmony is to be maintained. +\

“Indonesian Chinese will live with the memory of the 1998 riots for many years. During an interview, Susanto, an ethnic Chinese wholesaler, projected a video of the violence onto his wall. "I'm not showing you this to scare you. It's to remember," he said. But ethnic relations have improved so much, Susanto said, that today he has no complaints. "Day to day there is no discrimination," he said. "I think we have a good future here." +\

Anti-Chinese Sentiments Endure in Indonesia

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “For years, Indonesia was viewed as a perilous place for ethnic Chinese. In 2004, a U.S. court granted political asylum to an Indonesian national of Chinese descent who claimed that a return to her homeland would amount to a death sentence. She was just one among the tens of thousands of Chinese Indonesians who have fled the country. Many say the rise of Islamic fundamentalism has further marginalized ethnic Chinese. In one rural province, clerics recently disrupted a Chinese parade, arguing that the noise of firecrackers and running dragons interfered with Muslim prayer rites. "Many Indonesians still believe people with Chinese blood keep close allegiances to Beijing," said Andy Yentriyani, a leader of the National Commission on Violence Against Women. "The idea is that any freedoms or authority given the ethnic Chinese will come back to harm Indonesia." [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2010 /]

“Even now, as ethnic Chinese citizens run for office, prejudices continue. Sofyan Tan was recently defeated in a run for mayor in the city of Medan, the capital of northern Sumatra. In an interview, the city's first Chinese Indonesian political candidate said opponents waged a campaign to scare voters into believing he would sell the nation to China. "More hard work is required to show that leadership cannot be based on race and religion," he said. /

“For now, Ruminah isn't taking any chances about the return of ethnic violence. She runs her beauty shop out of her home, where she feels more secure. She has seen Muslim youths break off a relationship with her college-age daughter once they learn of her Chinese roots. And she misses her son, who never got the chance to come to terms with his Chinese heritage. Still, she says, she won't follow the ethnic Chinese who have fled Indonesia since the riots. "I'm not ashamed of who I am," she said. "This is my country. Where else can I go?" /

Discrimination Against Chinese in Modern Indonesia

“There’s much less discrimination now against Chinese-descendant citizens than there was in the Suharto era, and this is one of few remaining official policies, but it’s still very much in practice around here, and it’s very much felt,” Budi Setyagraha, head of the Yogyakarta chapter of Indonesia’s Chinese Muslim association told the Washington Post. “And it’s not just an economic issue, but also a symbolic one. We all built this nation, and we all deserve to be treated the same now.” [Source: Vincent Bevins, Washington Post March 18, 2017]

Reporting from Prambanan, Vincent Bevins wrote in the Washington Post: When Willie Sebastian bought a tiny piece of land to build a storage space, government officials in the heart of the island of Java delivered him an unpleasant surprise: He could not register the purchase, since he was of Chinese descent, and therefore the land would belong to the local sultan. The men at the land office knew he was Chinese, he said, even though his family had changed their last name from “Lee” in the 1970s, during his country’s right-wing dictatorship, to avoid discrimination. “They just looked at this face and knew,” Sebastian said recently, pointing to his light skin and eyes, while working in his humble general store outside the historic city of Yogyakarta. “But my family has been here for generations. They say the land can be owned by ‘natives,’ but I am native. Chinese Indonesians are Indonesians.” [Source: Vincent Bevins, Washington Post March 18, 2017

And here in Yogyakarta, a special region governed partially by a sultan with a lifelong position, Sebastian and others are pushing back against a 1975 decree that they think is being used against them unfairly. “My wife bought some land to open a convenience store near the airport, but it’s still not ours. They want us to rent our own land from the sultan, which we don’t accept,” says Siput Lokasari, a civil engineer who tried to take his case directly to the government with Sebastian. They received no response, despite recommendations from the National Commission on Human Rights that the policy be changed. “We are a minority. There’s been discrimination before this, and even though we have the law on our side now, a lot of other people are still afraid to speak up,” Lokasari said. Other local Chinese Indonesians, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said they had similar problems but chose not go to public for fear of hurting their cases.

“I don’t feel that regular people treat me differently because I’m Chinese. We get along great,” says Sebastian, as customers make their way around a set of pink children’s bicycles, his radio blasts the song “Every Morning” by the 1990s rock band Sugar Ray, and two women wearing light-colored headscarves work alongside him. “Right now my problem is the way the government is treating me.”

Chinese and Politics in Indonesia

In 2011, the Jakarta Post reported: “The political freedom that dawned with reform movement in 1998 has allowed an increasing number of Chinese-Indonesians to enter the political arena. They founded political parties in 1999, including the Indonesian Tionghoa Reform Party, Indonesian Reform Party and the Bhinneka Tunggal Ika Party. Unfortunately only Tunggal Ika won representation at the House of Representatives. [Source: Jakarta Post, February 2 2011 ==]

Jakarta Governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, known by his Hakka Chinese nickname as “Ahok,” was the most prominent politician of Chinese descent in decades. He was the first governor of Jakarta with Chinese ancestry and also the city's second Christian governor, following Henk Ngantung, who was governor from 1964–65. He was elected in 2012. Ahead of the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, Ahok's political rivals aligned themselves with Islamic extremists to exploit religious and racial intolerance, resulting in Ahok being accused of blasphemy in October 2016. He then lost the election to former Education Minister Anies Baswedan and was imprisoned for blasphemy. During the whole episode massive protest by conservative Muslims against its Christian governor were organized and some Indonesian Chinese worried they coould fuel anti-Chinese protests and even anti-Chinese violence.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022