CHINESE IN INDONESIA

Chinese roots in Indonesia that go back centuries. Even so they often been regarded as alien intruders by this overwhelming pribumi majority. Like their counterparts in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam, many are descendants of people from the southern Chinese province of Fujian who migrated to Southeast Asia at around the turn of the 20th century. Many Chinese are Christians. A smaller number are Buddhists, Taoists and Confucians. Although ethnic Chinese make up a small proportion of the population—roughly five to seven million people—they are often said to control a large share of the country’s wealth but it is unclear how true this is. A few prominently wealthy Chinese Indonesia contributes to the myth that the entire community is rich.

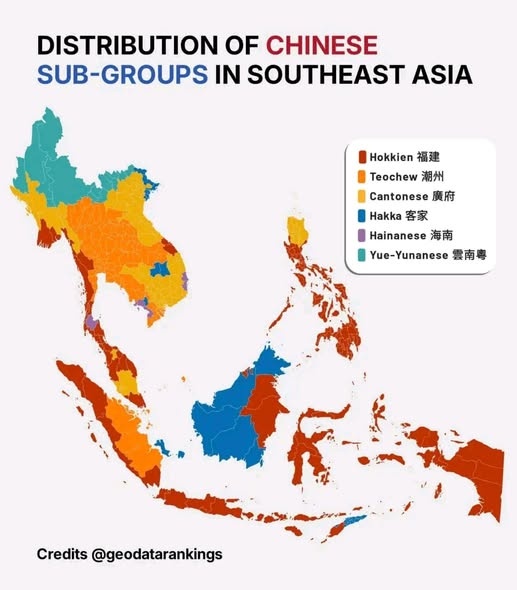

Assimilation for Chinese has been particularly difficult in Malaysia and Indonesia where Islamic practices discourage marriages involving Muslims and non-Muslims. For local people marrying a non-Muslim is also seen as rejection of Muslim-based nationalist pride. Many Chinese have Indonesian names. Hokkein, the Southern Min dialect of Fujian, is the primary dialect of many Overseas Chinese communities in Malaysia, Singapore Indonesia, and the Philippines. Since Chinese have traditionally been prohibited from speaking Chinese they have tended to study English. Peranakan Indonesian—a fusion of Indonesian, Javanese and Hokkein—is spoken in Indonesia.

Chinese influence in the visual arts can be seen along the entire north coast of Java from the batik patterns of Cirebon and Pekalongan, to the finely carved furniture and doors of Kudus in Central Java, as also in the intricate gold embroidered wedding costumes of West Sumatra. The Chinese minority of Java has also developed its own shadow puppets, combining Javanese and Chinese features. Chinese in Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia have the custom eating any time they feel like it.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, cultural assimilation of Chinese has been less common because of Islam and the emphasis placed "peoples of the soil" — which excludes Chinese — an important expression of ethnic and national identity that tends to impede intermarriage and full assimilation. By contrast, Chinese have tended to assimilate more readily in the Buddhist countries of mainland Southeast Asia such as Thailand. In some places, Chinese has been creolized with Southeast Asian languages. Peranakan Indonesian, formed from Indonesian, Javanese, and Hokkien, is used in Indonesia.

Identifying someone in Indonesia as a member of the Chinese (Tionghoa) ethnic group is not an easy matter, because the physical characteristics, languages, names, areas of residence, and lifestyles of Chinese Indonesians are not always distinct from those of the rest of the population. The national census does not record the Chinese as a special group, and there are no simple racial criteria for membership in this group. There are some people who consider themselves Chinese but who, as a result of intermarriage with the local population, are less than one-quarter Chinese in ancestry. On the other hand, there are some people who by ancestry could be considered half-Chinese or more but who regard themselves as fully Indonesian. Furthermore, many people who identify themselves as Chinese Indonesians cannot read or write the Chinese language. [Source: Library of Congress]

Chinese Population in Indonesia

Chinese altar to the Dead

It is estimated that there are at least 3 million Chinese-descended citizens in Indonesia, out of a population of approximately 290 million. Officially 2,832,510 Chinese were counted in Indonesia in 2010, which would mean they made up approximately 1.2 percent of Indonesia’s population.There are around 7 million people of partial Chinese ancestry, accounting for 3 percent of the population. Based on the official numbers Indonesian Chinese account for the fourth largest population of Chinese outside mainland China and Taiwan behind Thailand, Malaysia and the U.S. There are more Chinese in Malaysia than Singapore. [Source: Wikipedia]

Population numbers from Indonesia do not always reflect the full extent of Chinese presence. Partially assimilated Chinese are often not counted as Chinese. Around 6 million Chinese were counted in Indonesia (3 percent of the population) in the 2000s. One reason for the discrepancy in the population numbers for Chinese Indonesians is that there has been a lot of intermarrying between Chinese and other Indonesian groups over the years and defining what is Chinese is not always clear (Is a Chinese a pure blood Chinese or one that is 50 percent or 75 percent Chinese?)

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, A 2000 census put the number of ethnic Chinese in Indonesia at just 1.7 million — about 0.9 percent of the population — but the census asked people to identify their ethnic group, something that many Chinese would have been reluctant to do. Their real number is thought to be several times as high. About a third of Indonesia’s ethnic Chinese are reported to be Christian. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18, 2012]

History of Chinese in Indonesia

For centuries, people from China have been active in the thousands of islands that make up Indonesia, often as traders working alongside indigenous farmers and kings. Their numbers increased in the 19th century when the Dutch brought them in as laborers for plantations and mines. After the Dutch took over Jakarta in large numbers of Chinese seeking to make their fortune emigrated to what is now Indonesia. The Dutch tried to stem the migration but with little success. As times passed the Chinese became more numerous, their impact om the Indonesian economy.

The Chinese minority in Indonesia had long played a major economic role in the archipelago as merchants, artisans, and indispensable middlemen in the collection of crops and taxes from native populations. Chinese farmers collected taxes and worked as labor contractors for the Dutch; they were also moneylenders and dominated internal trade. The legendary successes of a few who amassed great wealth reinforced the stereotype of Chinese migration as a form of economic colonialism that exploited Southeast Asian resources and the Southeast Asian "peoples of the soil." [Source: Jean DeBernardi,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Library of Congress *]

In the late nineteenth century, emigration from China's southern provinces to Indonesia increased apace with economic development. Between 1870 and 1930, the Chinese population expanded from around 250,000 to 1,250,000, the latter being about 2 percent of the archipelago's total population. In some areas, such as the city of Pontianak in Kalimantan Barat and Bagansiapiapi in Riau Province, Chinese even came to form a majority of the population. They began to settle in rural areas of Java in the 1920s and 1930s.

Relations between Malay Indonesians and Chinese have long been shaped by both Dutch colonial rule and later Indonesian government policies. Under Dutch rule, Chinese were divided into totok, first-generation, fullblooded emigrants, and peranakan, native-born Chinese with some Indonesian ancestry who, like blijvers and Eurasians, had a distinct Indies life-style. Overseas Chinese lived for the most part in segregated communities. During the early twentieth century, the identity of overseas Chinese was deeply influenced by revolutionary developments in their homeland. *

Chinese junk arriving in Borneo

Assimilation of Chinese in Indonesia

The Indonesian government however promotes Bahasa Indonesia as the medium of education and public communication and has restricted Chinese-medium education and the Chinese-language press. An estimated 65 percent of Chinese Indonesians spoke Indonesian at home in the 1990s. The percentage is probably a lot higher now. [Source: Jean DeBernardi, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 |~|]

The policy of the Indonesian government by the early 1990s strongly advocated the assimilation of the Chinese population into the communities in which they lived, but the Chinese had a long history of enforced separation from their non-Chinese neighbors. The Chinese who immigrated to Indonesia were not linguistically homogeneous. The dominant languages among these immigrants were Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese. There was great occupational diversity among the Chinese in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but Dutch colonial policies channeled them into trade, mining, or skilled artisanship. In the twenty-first century, Chinese continue to dominate the Indonesian economy’s private sector, despite central government policies designed to promote non-Chinese entrepreneurs. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Nonetheless, Chinese are not a monolithic group. Not all are rich and urban. They seldom share a common language besides Indonesian or Javanese. One of the historical distinctions among Indonesian Chinese in the 1960s and 1970s—between the peranakan (localborn Chinese with some Indonesian ancestry) and totok (full-blooded Chinese, usually foreign-born)—has begun to fade as fewer foreign-born Chinese immigrate to Indonesia. Although the distinctiveness and social significance of this division vary considerably from place to place in the archipelago, ties to the Chinese homeland are weaker within the peranakan community, and there is stronger evidence of Indonesian influence. Unlike the more strictly male-dominated totok, peranakan families recognize descent along both female and male lines. Peranakan are more likely to have converted to Christianity (although some became Muslims) and to have assimilated in other ways to the norms of Indonesian culture. They typically speak Bahasa Indonesia as their first language. *

History of Discrimination Against Chinese in Indonesia

The history of prejudice against the Chinese goes back a long time. A massacre triggered by economic unrest in 1740, which left thousands of Chinese dead, prompted Dutch authorities to force Chinese Indonesians to live in ghettos and barred them from owning land or traveling without special permits. The Dutch colonial government imposed a system of racial divisions in Indonesia — as they did in Apartheid South Africa — which separated residents of Chinese descent from other groups. According to the “quarter system” Chinese were forced to live in separate urban neighborhoods and could travel out of them only with government permits. Most Chinese continued to settle in urban areas of Indonesia even after “quarter system” was discontinued in 1919.

Regions of China That Indonesian Chinese came from

At the same time, they also gave Chinese economic privileges over other ethnic groups. The Dutch designated Chinese as "foreign Orientals" and used Chinese traders as middlemen between colonial authorities and indigenous people, which aroused resentment among the local people. The Chinese never assimilated into the indigenous population. In the early 20th century, Muslim groups sometimes directed their anti-colonial feelings towards the Chinese.

Independence in 1949 brought a severe backlash, with the new government, led by a fiery nationalist, banning trade in rural areas by non-indigenous Indonesians and imposing other restrictions. Many of the modern laws concerning the Chinese population were passed during the Cold War.

In the early independence era in the 1950s written Chinese and the teaching of Chinese in school were banned. Chinese who did not have citizenship were deported. Those that remained were given the choice of learning the Bahasa Indonesian or are being deported themselves. In the 1960s the Indonesian government again prohibited the Chinese from exercising free choice of residence, requiring them to live in cities and towns. In 1960, Sukarno issued a decree banning "aliens" (Chinese) from doing business in the countryside. It was aimed at the Chinese engaged in the rural retail trade, long dominated by the Chinese. Nearly 100,000 Chinese were forced to shut down their businesses and return to China. Those that remained moved to the cities, where many struck it rich.

DISCRIMINATION TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

History of Violence Against Chinese in Indonesia

Chinese in Indonesia encountered considerable hostility from both Indonesians and Europeans, largely because of the economic threat they seemed to pose. In 1740, for example, as many as 10,000 Chinese were massacred in Batavia, apparently with the complicity of the Dutch governor general.

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: For much of Indonesia’s modern history, first under the dominance of the Dutch East India Co., then as a formal Dutch colony and, after 1949, as an independent nation, ethnic Chinese have rarely been able to live in peace. “No country harboring a Chinese minority possesses a blacker record of persecution and racial violence than Indonesia,” according to “Sons of the Yellow Emperor,” a study of overseas Chinese communities written by Lynn Pan, a leading authority on the subject. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012 +/]

In September 1965, six Indonesian army generals were killed by other high-ranking officers, and conservative generals backed by the United States responded by accusing Communist Party leaders of attempting to orchestrate a coup. According to the Washington Post: the failed led to a "spasm of horrific bloodletting targeted at ethnic Chinese and supposed supporters of the Indonesian Communist Party, or PKI, a revolutionary outfit that had been encouraged, funded and armed by Mao Zedong’s Communist regime in Beijing. " Over a period of months military and civilian groups killed an estimated 500,000 to 1 million people, exterminating the world’s third-largest Communist Party (behind China and the Soviet Union) while torturing and killing untold numbers of people accused of association with communists. [Source: Vincent Bevins, Washington Post, March 18, 2017 +/]

After the coup, there was a violent anticommunist reaction. By December 1965, mobs were engaged in large-scale killings, most notably in Jawa Timur Province and on Bali, but also in parts of Sumatra. Members of Ansor, the Nahdatul Ulama's youth branch, were particularly zealous in carrying out a "holy war" against the PKI on the village level. Chinese were also targets of mob violence. Estimates of the number killed — both Chinese and others — vary widely, from a low of 78,000 to 2 million; probably somewhere around 300,000 is most likely. Whichever figure is true, the elimination of the PKI was the bloodiest event in postwar Southeast Asia until the Khmer Rouge established its regime in Cambodia a decade later. [Source: Library of Congress]

DISCRIMINATION AGAINST CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; VIOLENCE TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN VIOLENCE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com; FALL OF SUKARNO, RISE OF SUHARTO AND THE MYSTERIOUS COUP OF 1965 factsanddetails.com

Chinese in Indonesia in the Suharto Era

Amid the chaos in 1965, a new regime led by Suharto, took over Indonesia and ruled it with an iron fist from 1965 until 1998. During the Suharto years, nearly all Chinese Indonesians obtained Indonesian citizenship, often at high cost and as a result of considerable government pressure. Popular resentment persisted toward Chinese economic success, however, and nurtured a perception of Chinese complicity in the Suharto regime’s corruption. Suharto placed rigid restrictions designed to wipe out Chinese identity on Chinese who chose to become Indonesian citizens. A 1967 presidential decree banned Chinese New Year celebrations and various Chinese arts. Despite this some wealthy Chinese businessmen prospered in the Suharto years presumably because they developed schemes in which the Suharto family were given large slices of the pie.

Vincent Bevins wrote in the Washington Post: “Suharto used domestic elements that already existed, such as some anti-Chinese sentiment, as well as the geopolitical situation and the perceived eternal threat of communism, to craft his policy on the local Chinese population,” said Baskara T. Wardaya, a professor at Sanata Dharma University at Yogyakarta who studies the role of the Cold War in Indonesian history. But it was discrimination with uneven results. Chinese Indonesians were effectively banned from public life, from participating in politics and the military, while their children found it hard to enter public schools or universities. At the same time, Suharto relied on powerful Chinese businessmen to build the economy, and many became very wealthy while common Chinese citizens were left behind.” [Source: Vincent Bevins, Washington Post March 18, 2017]

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: Discrimination against local Chinese became a pillar of Suharto’s authoritarian New Order regime. After rejecting forced emigration as a solution to the “Chinese problem,” authorities opted for coerced assimilation, banning Chinese newspapers, schools, festivals and other expressions of identity different from that of the indigenous majority. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012]

“Under Suharto, everything Chinese was suppressed,” said Myra Sidharta, an 85-year-old, third-generation Chinese Indonesian who has chronicled the Chinese minority. Sidharta said that she sometimes played golf with Suharto before he seized power and that she found him “very boring” but not a frothing bigot. His anti-Chinese policies, she said, derived from a political calculation that the relatively well-off Chinese minority served as an easy and popular scapegoat.

Chinese in Indonesia After Suharto

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post: “The crumbling of Suharto’s dictatorial authority in 1998 initially proved a nightmare for Indonesian Chinese as pro-democracy student demonstrations morphed into an orgy of rioting that hit Chinese-owned shops and homes with particular fury. But, as the country stabilized into a functioning democracy, the first elected president, the liberal-minded Muslim cleric Abdurrahman Wahid, and his successors introduced legal and social reforms aimed at undoing past discrimination. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 18 2012]

Chinese Temple in Denpasar, Bali

In May 1998, riots broke out in which hundreds of Chinese stores were burned and Chinese women were raped and murdered. When many Chinese Indonesians fled the violence, the subsequent capital flight resulted in further economic hardship in a country already suffering a financial crisis. By 2005 many had returned, but the economic and social confidence of many Chinese in the country was badly shaken by the experience.

The Suharto government’s program of assimilation for the Chinese began to be phased out in 1998. Post-Suharto governments lifted bans on expressions of Chinese culture and revised nationality rules. Long-discouraged symbols of Chinese identity such as Chinese-language newspapers, schools, and public rituals, and the use of Chinese names, no longer were subject to strict regulation. The government even declared Confucianism an official religion with Islam, Hinduism, Catholicism, Protestantism and Buddhism. The Ministry of Religious Affairs now has a special unit dedicated to promoting and protecting Confucian ethics despite the fact that even China does not consider Confucianism a religion.

Indonesian Chinese Homes

Jill Forshee wrote in “Culture and Customs of Indonesia”: Indonesian Chinese homes often differ from those of indigenous Indonesians. Those called “shop-houses,” accent the merchant class status of Chinese in Southeast Asia, especially in Indonesia. As noted by Jacques Dumarcay, in The House of Southeast Asia: “In Southeast Asia, the Chinese house is essentially urban and its plan is thus dependent on the layout of the town.” [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

“ Since cities are crowded, so is housing and commercial spaces, which Chinese often combine. Many live above or behind their businesses in long, narrow structures resembling urban shops in the West. Often family members wander in and out of the commercial and living spaces, and many will sit in front of their shops in the evenings to socialize with neighbors or enjoy cool air. When not too limited by space, Chinese homes include an open-air central outdoor courtyard surrounded on four sides by rooms. These dwellings provide a pleasant sense of natural space and often caged songbirds, flowering plants, vegetable gardens, or even fruit trees enliven these family enclosures.

“Households might shelter several family generations and contain considerable “1floor space. Because these are walled environments, people live in relative privacy from the outside. Chinese Indonesians also occupy homes like those of others, such as Dutch colonial houses and the common, modern types already described. In urban areas, many wealthy Chinese live in newer, expensive homes in upscale sections of town. Their homes can be lavish, surrounded by high concrete walls embedded with broken glass at the top to keep robbers at bay. Similar walls provide protection for most urban residences of the middle- or upper-classes, along with foreigners living in Indonesia.”

Potehi: Chinese Puppetry in Indonesia

Potehi puppetry, a kind of Chinese puppetry performed in Indonesia, is said to have originated on the Chinese mainland during the Shang Dynasty about 3,000 years ago, The word potehi comes from the words poo (kain/cloth), tay (kantung/pocket), and hie (wayang/puppet). The puppets, about 30 centimeters tall, have a similar shape to the unyil (children’s cartoon) puppets made from cloth. Each doll has an individual face. [Source: Lutfi Retno Wahyudyanti, Jakarta Post, March 20, 2009 |~|]

According to Jakarta Post: “There are darkly colored dolls with angry faces and brightly colored dolls with happy faces, which wear colorful dresses decorated with beautiful embroidery. The puppeteer manipulates the dolls from below using both his hands, yet can play two characters at the same time. He may have an assistant for more characters.” |~|

“Potehi has increasingly rare as few people are interested in maintaining the tradition. Puppeteers in Solo and Surabaya are ethnic Javanese, leaving only one puppeteer of Chinese descent, who lives in Semarang. If the Potehi puppets become extinct. It is mainly because of a 1967 presidential decree, which forced ethnic Chinese to integrate, costing them their Chinese identity. Under this law, Chinese New Year celebrations and various Chinese arts were prohibited. |~|

Chinese Puppetry Hangs on in Indonesia

Lutfi Retno Wahyudyanti wrote in the Jakarta Post: “In the middle of busy Semawis Market in Semarang, dozens of people stood staring, apparently transfixed by a red box, from which issued the sounds of traditional Chinese music. Before long, a golden puppet appeared, decorated with the picture of a dragon – the king. The Potehi puppet show had begun. Inside the box, 75-year-old Teguh Chandra and his assistant performed their show, accompanied by three musicians playing a range of traditional instruments. [Source: Lutfi Retno Wahyudyanti, Jakarta Post, March 20, 2009 |~|]

Teguh Chandra “got the chance to return to the stage after former president Abdurrahman Wahid revoked the 1967 presidential decree. Teguh’s first shows were performed in 1999 in the Ismail Marzuki Park at the invitation of Gadjah Mada University and the Kencana Solo University. The stage shows, although legal again, have lost their prestige and popularity and, as each show runs for three or more days, are finding it difficult to compete with television programs and modern entertainment. Furthermore, the long prohibition means interest in becoming a puppeteer has disappeared, and Teguh has never had a student. |~|

“Well before the performances were prohibited, who wanted to learn how to be a puppeteer?” asks Teguh, now the only person of Chinese descent running Chinese Potehi puppets shows. “Even now, among those who are on the stage, only a few want to continue because it is difficult to rely on this as a source of income.” |~|

Life of Chinese Puppeteer in Indonesia

Lutfi Retno Wahyudyanti wrote in the Jakarta Post: “Thio Tiong Gie, better known as Teguh Chandra, was born in January 1933 in Demak, where he taught himself his Potehi puppeteering skills. “A long time ago my father had a fabric shop in Demak,” he says. “We went bankrupt because the shop was robbed in 1942. My father even went to prison.” After that, the family Teguh is one of five children – moved to Kaligawe.“At that time we earned an income from selling snacks. My father bought newspapers to wrap the snacks.” In one newspaper was a pakem [a traditional puppet story] about the Potehi puppets.” [Source: Lutfi Retno Wahyudyanti, Jakarta Post, March 20, 2009 |~|]

“Teguh liked the story and memorized it. Some years later, he met a friend of his father who was recruiting puppeteers who could perform with the Potehi puppets. Because Teguh wanted a job he claimed that he had the necessary skills. He was the right person for the job, he said, because he liked history and was a good performer. He had a week to learn how to run a Potehi puppet show, before he was asked to go on stage in Cianjur. “This stage event was a big success,” Teguh recalls. “The audiences liked me and I was asked to perform again.” |~|

Teguh then started to seriously learn how to become a Potehi puppeteer. He had success in various places, especially along the north coast of Java, although he had only one play. Those who came to watch his Potehi puppet shows were from both the ethnic Chinese community and the indigenous Indonesian community. Eventually, word of his success reached the ears of a famous Potehi puppeteer called Tan Ang Ang. “I got a letter from him. He asked me to go to Blitar. There I was given 10 books of pakem for Potehi puppets. After that I started to perform various pakem.” |~|

“During this time, Teguh Chandra, a Confucian, also became a teacher of religion, being active as an itinerant preacher. He also ran services for those wanting a prayer ceremony or help with prayers for funerals. And so Thio Tiong Gie (as he then was) could no longer stage his Potehi puppet plays. He kept his dolls, some of which are hundreds of years old, in a big case, cleaning them occasionally to keep them in good condition. He also had to change his name to something more Indonesian and, following the Internal Affairs Minister’s Decree in 1978 allowing only five official religions, was forced to register himself as a Buddhist. Forced out of his job, the man now known as Teguh headed to Tegal, recalling from his stage shows that there were many welders working there. He tried to make doors and window bars and started a welding workshop.” |~|

Chinese and Business In Indonesia

In Indonesia the Chinese are regarded as hardworking and enterprising. One housewife from eastern Java told the New York Times, "They work harder. In a Chinese family you see the mother working, the kids working, everyone working. Sometimes we feel jealous. We think, why are we Javanese below the Chinese?"

Overseas Chinese controlled much of the commerce in Thailand, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia and Indonesia in the 19th and 20th century and were involved in businesses throughout the Asian-Pacific region in the same period. But while most ethnic Chinese are considered to be members of the wealthy merchant class, many are actually small-business men, shopkeepers or traders.

Under the Dutch, the Chinese were prominent merchants. Under Suharto, Chinese tycoons became extremely wealthy while ordinary Chinese prospered as small businessmen but were regarded with suspicion by many Indonesians. Today Chinese own shops, restaurants, hotels, banks, industries. Only a small percentage are very wealthy. Most are small business owners.

During the Asian financial crisis many Chinese lost their jobs and ways of making a living. After the crisis in 1998, many Chinese businessmen in Java left the island and opened up new businesses off of Java, being careful however not compete with local businesses. In Bali for example they opened up 24-hour mini marts, Internet cafes and small craft factories—businesses that hadn't even existed before.

See Family-Style Businesses Under CHINESE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Wealthy Chinese in Indonesia

By one estimate, the Chinese make up 4 percent of the population but control about 70 percent of Indonesia's wealth. Under Suharto, 27 of Indonesian's 35 largest private businesses were run by Chinese tycoons. The only ones that weren’t were run by Suharto's children, often in conjunction with Chinese businessmen. The Chinese have traditionally relied on political connections to prosper. They have also been a magnet for foreign investment, much of it from non-Indonesian Chinese in places like Taiwan and Singapore.

The success of the Chinese is widely envied and resented in Indonesia. Many Chinese have amassed their vast fortunes by exploiting Indonesian workers and laborers on plantations and in factories. One laborer in east Java told the New York Times, "We're being monopolized by the Chinese. The Chinese should be kicked out! Then we would be freed of them forever."

The Chinese have traditionally kept a low profile so as not to arouse to much resentment over their wealth. Most rich Chinese don't like to flaunt their wealth out of fear of upsetting the Muslim majority. Even so many live in spacious houses and have Indonesian chauffeurs and servants.

Ethnic Chinese tycoons were hit hard by the Asian financial crisis. Many remained technically bankrupt for a long time afterwards.

See Rich

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025