OLDEST KNOWN WINE — FROM CHINA

Vessels with the

oldest wine

The earliest evidence of wine making has been found in China: traces of a mixed fermented drink made with rice, honey, and either grapes or Hawthorne fruit found on pottery shards dated to 7,000 B.C. found near the village of Jiahu in Henan Province northern China. Wine has also reportedly been found on a pottery sample from a Chinese tomb dated to 5000 B.C.

Analysis by University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of the pores of 9000-year-old pottery shards jars unearthed in Jiahu turned up traces of beeswax, a biomarker for honey; tartaric acid, a biomaker for grapes, wine and Chinese hawthorne fruit; and other traces that “strongly suggested” rice.

Grapes were not introduced to China from Central Asia until many millennia after 7000 B.C., so it is reasoned the tartaric acid likely comes from hawthorne fruit which is ideal for making wine because it has a high sugar content and can harbor the yeast for fermentation. Wine traces has also been found in a pottery sample from a Chinese tomb dated to 5000 B.C.

This findings raises the question: which came first grape wine or rice wine. Grape pips, an indication of possible wine making operations, have been found in six millennium B.C. sites in the Dagestan mountains in the Caucasus.

See Separate Articles:

JIAHU (7000-5700 B.C.): CHINA’S EARLIEST CULTURE AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com

ORIGIN OF ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com ;

DRINKS IN MESOPOTAMIA: MAINLY BEER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DRINKS: BEER, WINE, MILK AND WATER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKING AND DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKS AND DRUGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton Science Library)

by Patrick E. McGovern (2019) Amazon.com;

“Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages”

by Patrick E. McGovern (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours” by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, et al. (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Ancient History of Wine: Food and Nutrition in History and Antropology” by Patrick E. McGovern, Stuart J. Fleming, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

“Brewing Barley Wines: Origins, History, and Making Them at Home Today” by Terry Foster (2024) Amazon.com;

“Beer's Ancient Cradle: Exploring the Origins and Rituals of Humanity's Favorite Brew” by Maxwell J Aromano (2023) Amazon.com;

“Michael Jackson's Great Beer Guide” by Michael Jackson and Sharon Lucas (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

"First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies" by Peter Bellwood (2004) Amazon.com;

“Birth Gods and Origins Agriculture” by Jacques Cauvin (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective” by C. Wesley Cowan, Paul Minnis, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Cooking: Palaeolithic and Neolithic Cooking”

by Ferran Adrià (2021) Amazon.com;

“Plant Foods of Greece: A Culinary Journey to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages” by Soultana Maria Valamoti (2023) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cookery, Recipes and History,” by Jane Renfrew (English Heritage, 2006) Amazon.com

World's Earliest Grape Winemaking in Georgia

The earliest evidence of grape wine was found in clay pottery from Khramis Didi Gora, Georgia dated to to 6,000 B.C. Ashifa Kassam and Nicola Davis wrote in The Guardian: “A series of excavations in Georgia has uncovered evidence of the world’s earliest winemaking, in the form of telltale traces within clay pottery dating back to 6,000 B.C. – suggesting that the practice of making grape wine began hundreds of years earlier than previously believed. While there are thousands of cultivars of wine around the world, almost all derive from just one species of grape, with the Eurasian grape the only species ever domesticated. [Source: Ashifa Kassam and Nicola Davis, The Guardian, November 13, 2017 +/]

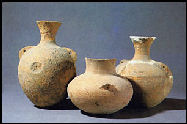

Clay jar from Khramis Didi Gora, Georgia

“Until now, the oldest jars known to have contained wine dated from 7,000 years ago, with six vessels containing the chemical calling cards of the drink discovered in the Zagros mountains in northern Iran in 1968. The latest find pushes back the early evidence for the tipple by as much as half a millennium. “When we pick up a glass of wine and put it to our lips and taste it we are recapitulating that history that goes back at least 8,000 years,” said Patrick McGovern a co-author of the study from the University of Pennsylvania museum of archaeology and anthropology, who also worked on the earlier Iranian discovery. +/

“The find comes after a team of archaeologists and botanists in Georgia joined forces with researchers in Europe and North America to explore two villages in the South Caucasus region, about 50km south of the capital Tbilisi. The sites offered a glimpse into a neolithic culture characterised by circular mud-brick homes, tools made of stone and bone and the farming of cattle, pigs, wheat and barley. Researchers were particularly intrigued by fired clay pots found in the region – likely to be some of the earliest pottery made in the Near East. Indeed, one representative jar from a nearby settlement is almost a metre tall and a metre wide, and could hold more than 300 litres. What’s more, it was decorated with blobs that the researchers say could be meant to depict clusters of grapes. +/

“To explore whether winemaking was indeed a part of life in the region, the team focused on collecting and analysing fragments of pottery from two neolithic villages, as well as soil samples. Radiocarbon dating of grains and charcoal nearby suggested the pots date to about 6,000–5,800 BC. In total, 30 pottery fragments and 26 soil samples were examined, with the inside surface of the pottery ground down a little to produce a powder for analysis. While many of the pieces were collected in recent excavations, two were collected in the 1960s; researchers have long suspected they might bear traces of wine.The team then used a variety of analytical techniques to explore whether the soil or the inner surface of the vessels held signs of molecules of the correct mass, or with the right chemical signatures, to be evidence of wine. +/

“The results, published in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, reveal that for eight of the fragments, including the two previously unearthed, the team found traces of tartaric acid – a substance found in grapes in large quantities. Tests on the associated soils largely showed far lower levels of the acid. The team also identified the presence of three other acids linked to grapes and wine. Other evidence indicating the presence of wine included ancient grape pollen found at the excavated sites – but not in the topsoil – as well as grape starch particles, the remains of a fruit fly, and cells believed to be from the surface of grapevines on the inside of one of the fragments. +/

“While the team note that it is possible that the vessels were used to store something other than wine, such as the grapes themselves, they note that the shape of the vessels is suited to holding a liquid and that grapes or raisins would have degraded without trace. Moreover, there are none of the telltale signs that the pots were used for syrup-making, while grape juice would have fermented within a matter of days. +/

“The findings suggest the sites were home to the earliest known vintners, besting the previous record held by the traces of Iranian wine found just 500km away and dated to 5,400-5,000 BC. Older remnants of winemaking have also been found at the Jiahu site in China’s Henan province, dating back to 7,000BC, but the fermented liquid appeared to be a mixture of grapes, hawthorn fruit, rice beer and honey mead. +/

“With their narrow base, the large clay pots used do not stand up easily, suggesting they might have been half buried in the ground during the winemaking process, as was the case for the Iranian vessels and which is a traditional practice still used by some in Georgia. Davide Tanasi, of the University of South Florida, said the results of the study were unquestionable and that the findings were “certainly the example of the oldest pure grape wine in the world”. +/ “The excavations in Georgia were largely sponsored by the National Wine Agency of Georgia. “The Georgians are absolutely ecstatic,” said Stephen Batiuk, an archaeologist from the University of Toronto and one of the study’s co-authors. “They have been saying for years that they have a very long history of winemaking and so we’re really cementing that position.” +/

Evidence of 6,000-Year-Old Wine Found in Sicilian Cave

Monte Kronio, Sicily

Residue probably from grape wine found on terracotta jars in Sicily suggests that wine was being made and consumed on the island in the fourth millennium B.C. Lorenzo Tondo wrote in The Guardian: “Researchers have discovered traces of what could be the world’s oldest wine at the bottom of terracotta jars in a cave in Sicily, showing that the fermented drink was being made and consumed in Italy more than 6,000 years ago. Previously scientists had believed winemaking developed in Italy around 1200 BC, but the find by a team from the University of South Florida pushes that date back by at least three millennia. “Unlike earlier discoveries that were limited to vines and so showed only that grapes were being grown, our work has resulted in the identification of a wine residue,” said Davide Tanasi, the archeologist who led the research. “That obviously involves not just the practice of viticulture but the production of actual wine – and during a much earlier period,” Tanasi said. [Source: Lorenzo Tondo, The Guardian, August 30, 2017 ~]

“Published in the Microchemical Journal, the finding was significant because it was “the earliest discovery of wine residue in the entire prehistory of the Italian peninsula”, the researchers said. The five organic residue samples taken from late copper age storage jars found in 2012 in a limestone cave on Monte Kronio, near the fishing harbour of Sciacca on Sicily’s south-west coast, were dated to the fourth millennium BC. “We conducted chemical analysis on the ancient pottery and identified the presence of tartaric acid and its salt,” Enrico Greco, a chemistry researcher at the University of Catania who was involved in the research, told the Guardian.

“Known as cream of tartar, the salt of tartaric acid, which is the main acid component in grapes, develops naturally during winemaking. “The presence of these molecules allows us to confirm the use of this vessel as a wine container,” Greco said. While some experts have suggested humans may have been making wine as long as 10,000 years ago, the earliest known evidence of winemaking – also about 6,000 years old – was uncovered in 2011 near the village of Areni in Armenia.

But in that case scientists said they could not exclude the possibility that traces of malvidin found in the residue they recovered could have come from pomegranates, a common fruit in Armenia and its national symbol. In the Sicilian find, the malvidin can only have come from grapes since pomegranates did not exist in the area. The discovery “fills us with joy”, said Alessio Planeta, a winemaking expert and historian from the area, which remains one of Italy’s most important wine-producing regions. “Before this, we used to thinking Sicily’s wine culture arrived with the island’s colonisation by the ancient Greeks.”

First Wine in Iran

An archaeological site called Hajii Firuz (Firuz Tepe) in the Zagros mountains in Iran with mud brick-buildings dating to 5400-5000 B.C. yielded jars with traces of tartaric acid (a chemical indicator of grapes), calcium tartrate and terebinth resin, which are left behind by dried wine. There were also remains of stoppers which could have been placed in the jars to prevent wine from tuning into vinegar. Based on the colors of the residues, the Neolithic people that lived there enjoyed both red and white wine. The site was identified by a team lead by Patrick McGovern, an ancient-wine expert and a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, in 1996.

Ceramic remains unearthed at Godin Tepe in the Zagros Mountains suggest that wine was produced there about 3,500 B.C., pushing back the earliest documented evidence of wine making by about 500 years. The discovery was made by a graduate student at the Royal Ontario Museum who noticed a stain on a vessel she was assembling. When the stain was analyzed it revealed tartaric acid, a substance found abundantly in grapes. If the stain was indeed made from wine it shows that wine-making and writing evolved about the same time. [National Geographic Geographica, March 1992].

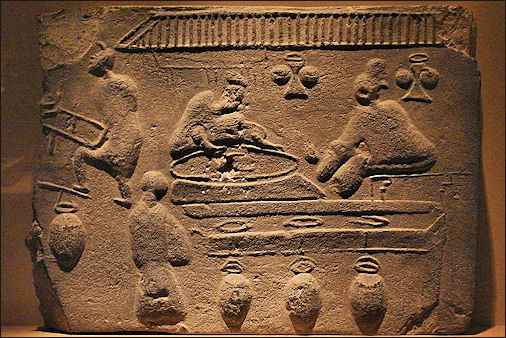

brick showing wine making in ancient China

World’s First Winery in Armenia

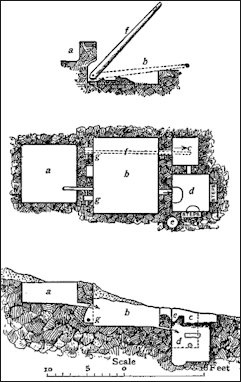

In January 2011, a team led by UCLA’s Gregory Areshian announced they had found the world's oldest known winery near the village of Areni, Armenia in the same cave where the oldest known shoe — a well-preserved, 5,500-year-old leather moccasin — was found. Located near a burial site, the “winery” consists of a wine press for stomping grapes, fermentation and storage vessels, drinking cups, and withered grape vines, skins, and seeds. "This is the earliest, most reliable evidence of wine production," Areshian told National Geographic. "For the first time, we have a complete archaeological picture of wine production dating back 6,100 years," he said. [Source: James Owen, National Geographic News, January 10, 2011; Marc Kaufman, Washington Post, January 11, 2011]

"This is the oldest confirmed example of winemaking by a thousand years," Gregory Areshian, an archaeologist and co-director of the dig, told the Washington Post . "People were making wine here well before there were pharaohs in Egypt." The winemaking in the cave appears to be associated with burial rituals because numerous graves are close by, he said. "This was almost surely not wine used at the end of the day to unwind." Although researchers traditionally look to Egypt and Mesopotamia to understand ancient civilization, Areshian said that "there were many, many specialized and unique centers of civilization in the ancient world, and we can only understand it as a mosaic of these peoples."

Areni is remote Armenian village, within 60 miles of Mount Ararat, where Noah is said to have planted a vineyard, harvested grapes, fermented them and got drunk, The prehistoric winemaking equipment in Areni was first detected in 2007, when excavations co-directed by Areshian and Armenian archaeologist Boris Gasparyan began at the Areni-1 cave complex. In September 2010 archaeologists completed excavations of a large, 2-foot-deep (60-centimeter-deep) vat buried next to a shallow, 3.5-foot-long (1-meter-long) basin made of hard-packed clay with elevated edges.

Chinese ritual vessels

The shape and placement of the wine press indicates locals stamped the grapes with their feet, as people throughout the Mediterranean and Near East did as late as the 19th century, and collected the wine in fermentation jars placed below to capture the liquid, Areshian said. Juice from the trampled grapes drained into the vat, where it was left to ferment, he explained. The wine was then stored in jars — the cool, dry conditions of the cave would have made a perfect wine cellar, according to Areshian, who co-authored a study on the finding in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

To test whether the vat and jars in the Armenian cave had held wine, the team chemically analyzed pottery shards — which had been radiocarbon-dated to between 4100 B.C. and 4000 B.C. — for telltale residues. The chemical tests revealed traces of malvidin, the plant pigment largely responsible for red wine's color. "Malvidin is the best chemical indicator of the presence of wine we know of so far," Areshian said. McGovern agrees the evidence argues convincingly for a winemaking facility but said the claim could be made stronger if the presence of tartaric acid was found. Malvidin, he said, might have come from other local fruits, such as pomegranates.

Implications of the World’s First Winery in Armenia

Marc Kaufman wrote in the Washington Post, "Establishing vineyards with domesticated and high-yielding Vitis vinifera, the hybrid grape still used to make wine today, is a significant advance, and is considered more complex than making beer from the grains that dominated in the fertile lowlands. The Areni area also had orchards at the time of the early winemaking because the cave has remains of plums and apricots. [Marc Kaufman, Washington Post, January 11, 2011] McGovern called the discovery "important and unique, because it indicates large-scale wine production, which would imply, I think, that the grape had already been domesticated." This finding is consistent with previous DNA studies of cultivated grape varieties that pointed to the mountains of Armenia, Georgia, and neighboring countries as the birthplace of viticulture. [Source: James Owen, National Geographic News, January 10, 2011]

Ancient Palestine wine press McGovern said the Areni grape perhaps produced a taste similar to that of ancient Georgian varieties that appear to be ancestors of the Pinot Noir grape, which results in a dry red. To preserve the wine, however, tree resin would probably have been added, he speculated, so the end result may actually have been more like a Greek retsina, which is still made with tree resin.

The location of a winemaking facility and drinking cups near an ancient burial ground is significant. Areshian has speculated that winemaker’s drinking culture likely involved ceremonies in honor of the dead. He told National Geographic, "Twenty burials have been identified around the wine-pressing installation. There was a cemetery, and the wine production in the cave was related to this ritualistic aspect...I guess a cave is secluded, so it's good for a cemetery, but it's also good for making wine...And then you have the wine right there, so you can keep the ancestors happy."

The discovery is important, the study team says, because winemaking is seen as a significant social and technological innovation among prehistoric societies. Vine growing, for instance, heralded the emergence of new, sophisticated forms of agriculture. "They had to learn and understand the cycles of growth of the plant," Areshian said. "They had to understand how much water was needed, how to prevent fungi from damaging the harvest, and how to deal with flies that live on the grapes...The site gives us a new insight into the earliest phase of horticulture — how they grew the first orchards and vineyards.”

University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Naomi Miller commented that "from a nutritional and culinary perspective, wine expands the food supply by harnessing the otherwise sour and unpalatable wild grape. "From a social perspective, for good and ill," Miller said, "alcoholic beverages change the way we interact with each other in society."

Archeology at Areni Cave

Marc Kaufman wrote in the Washington Post, "The discovery, and painstaking process of determining that it was wine being made and stored, adds to the importance of the Areni cave, which in 2009 yielded the oldest known leather shoe and a red basket buried alongside an infant. The mocassin, made of leather and straw, was carbon-dated to be about 5,500 years old. It is highly unusual for organic material to remain intact so long, but the dry conditions of the cave, its constant temperature and then a covering layer of sheep dung deposited long ago have created a treasure trove of objects from the period called the Copper Age. The age of the finds was set through carbon dating and uncovering archaeological layers. [Marc Kaufman, Washington Post, January 11, 2011]

The cave expedition, which was sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences in Armenia, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the National Geographic Society, began in 2007, after archaeologists noticed some seemingly ancient grape seeds. But the cave complex had been identified as potentially important for archaeology in the late 1970s.

Areni Cave

As Areshian explained it, geologists hired by defense officials of the former Soviet Union combed the countryside, and the Caucases in particular, to find deep caves where important material and documents could be stored in the event of a nuclear war with the United States. This cave in the northern Zagros Mountains, near Armenia's southern border with Iran, struck one of the geologists as unique. Areshian, then an archaeology graduate student in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, was summoned. He made a quick survey of the place and promised himself that he would someday return.

About 3500 BC, Areshian said, the area apparently experienced a major earthquake that cut off much access to the caves. In a short time, he said, the complex went from being an important gathering place to a popular shepherd destination.

Areshian's team used a new approach to determining whether wine residue was present - testing for the plant pigment malvidin, the heart-healthy flavonoid that gives red wine its color. Previously, researchers had largely tested for tartaric acid, which Areshian said is present in wine but in other plants as well.

McGovern, who based his wine-storage finding from Iran on the archaeology of the site and the presence of tartaric acid, disagreed that the malvidin was needed to prove the presence of wine. But he said its presence at the Armenian site added to the weight of evidence. "You have in the cave good evidence of the kind of wine treading on a large scale that you later see around the area," he said. "I think this tells us the people there had been domesticating grapes and making wine for some time."

Wine Used in Ritual Ceremonies 5000 Years Ago in Georgia

According to Ca' Foscari University of Venice: Wine was used in ritual ceremonies 5000 years ago in Georgia, which some regard as the cradle of viticulture Georgian-Italian archaeological expedition of Ca' Foscari University of Venice in collaboration with the Georgian Museum of Tbilisi has discovered vine pollen in a zoomorphic vessel used in ritual ceremonies by the Kura-Araxes population. In the archeological site of Aradetis Orgora, 100 kilometers to the west of the Georgian capital Tbilisi, Ca' Foscari's expedition led by Elena Rova (Ca' Foscari University of Venice) and Iulon Gagoshidze (Georgian National Museum Tbilisi) has discovered traces of wine inside an animal-shaped ceramic vessel (circa 3,000 BC), probably used for cultic activities. [Source: Ca' Foscari University of Venice, June 14, 2016]

“The vessel has an animal-shaped body with three small feet and a pouring hole on the back. The head is missing. It was found, together with a second similar vessel and a Kura-Araxes jar, on the burnt floor of a large rectangular area with rounded corners, arguably a sort of shrine used for cultic activities. Results of radiometric (C14) analyses confirm that the finds date to circa 3000-2900 BC Both zoomorphic vessels are an unicum in the region.

“The vessel, examined by palynologist Eliso Kvavadze, contains numerous well-preserved grains of pollen of Vitis vinifera (common grape vine), which shows wine's strategic role in the Kura-Araxes culture for ritual libations. According to professor Rova, this is a significant discovery, "because the context of discovery suggests that wine was drawn from the jar and offered to the gods or commonly consumed by the participants to the ceremony."

It's a key-finding for Georgia, where grapewine has been cultivated since the Neolithic period. Now the Georgian wine culture has been dated back to the Kura-Araxes period, more than 5,000 years ago and is still continuing: in the course of traditional Georgian banquets, the supra, wine is consumed from vessels derived from animal horns in the context of elaborated ritual toasts. The Kura-Araxes culture (second half of the fourth and first half of the third millennium BC) is the only prehistoric culture of the Southern Caucasus which spread over large areas of the Near East, reaching Iran and the Syro- Palestinian region.”

Early Wine Grapes and Early Wine Production

Early wine was probably made from the wild Eurasian grape (“Vitis vinifera sylvestris”), which grows wild throughout the temperate Mediterranean, and south, west and central Asia. Later domesticated grapevines — now accounting for 99 percent of the world’s wines — were developed from wild Eurasian grapevines. Domesticated grapevine are self-pollinating, hermaphroditic plants that yield larger and juicier grapes. Transplanted to irrigated regions where didn't grow before, the Eurasian vines are the source of nearly all modern wine-producing grapes, whether red pinot noirs or white Chardonnay.

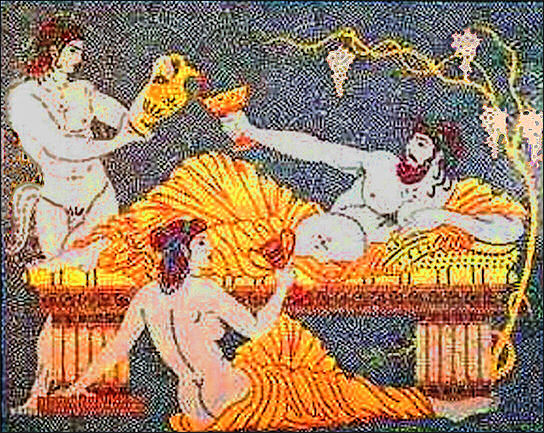

Dionysos mosaic

The first domesticated grapevines are believed to have been developed in the northern Near East, perhaps in Armenia or perhaps in the Zagros mountains of Iran, where wild grapes still grow today and pollen cores show they grew in Neolithic times. By 3000 B.C. domesticated grapes had been transplanted to the Jordan Valley, which became a major exporter of wine. It produced large amounts of wine that was traded to Egypt and elsewhere. An Egyptian King named Scorpion who was buried in 3150 B.C. with 700 jars of imported wine.

Between 3000 and 2700 B.C. the Egyptians were marketing wines in amphorae with labels that indicated the year, the contents, where it was produced, the owner of the vineyard and the quality with the best being rated as “very, very good.” . Between 3000 and 2500 B.C. winemaking became a major export business in what is now Shiraz in Iran. The Sumerians and other Mesopotamian groups were major buyers. Viticulture arrived in Crete in 2500 B.C. From there it made its way to Greece. A Greek drinking cup from the 6th century B.C. shows the god Dionysus carrying grapes in a ship across the Mediterranean. Between 200 and 100 B.C. General Zhang brought grape cuttings from Central Asia to the Chinese Emperor.

Wine Grapes from Turkey and the Noah Hypothesis

In 2016, 5,000-year-old grape seeds were found near a 8,500-year-old mound located in western Izmir province in Turkey. The Daily Sabah reported: “The seeds were uncovered in Yassitepe Mound located in Bornova district, which is very close to the nearby 8,500-year-old Yesilova Mound, the oldest settlement near Turkey’s third largest city Izmir. [Source: dailysabah.com, October 9, 2016]

“The seeds are presumed to be that of the renowned Bornova Muscat grape. The head of the excavation team, Assoc. Prof. Zafer Derin said that the seeds, which were found in carbonized form at the bottoms of pottery, could be the oldest grape remains in the Izmir area. Derin added that the seeds could help reveal important details regarding life in Western Anatolia during antiquity. Anatolia is regarded as one first the regions were grapes are being cultivated in history, with western provinces of Izmir, Aydin and Manisa being the most prominent centers of grape production in Turkey.”

William Cocke wrote in National Geographic News: “The wild Eurasian grapevine (Vitis vinifera sylvestris) is found from Spain to Central Asia. Cultivars, or varieties bred from the vine, account for nearly all of the wine produced today.McGovern is attempting to establish the origin of the earliest Neolithic viniculture—where grapevines were cultivated and winemaking developed. By comparing DNA from the wild grape with that of modern cultivars, McGovern and his colleagues hope to pinpoint the origin of domestication. [Source: William Cocke, National Geographic News, July 21, 2004 */]

“The scientist recently returned from an expedition to Turkey’s Taurus Mountains near the headwaters of the Tigris River. There, he combed rugged river valleys in search of wild grapevines untouched by modern cultivation methods. McGovern was joined by José Vouillamoz, from Italy’s Istituto Agrario di San Michele all’Adige in Trento, and Ali Ergül, from Turkey’s Ankara University. */

muscat grapes

““We’re looking in eastern Turkey, because that’s where other plants were domesticated,” McGovern said. “We’re going out there to collect wild grapevines with local cultivars, so we can see what the relationship is and maybe make a case that this is where the first domestication occurred.” */

“One dramatic setting for the researchers’ grapevine collecting was a deeply cut ravine below the site known as Nemrut Daghi. “A first-century B.C. ruler, Antiochus I Epiphanes, had statues of himself in the company of the gods hewn out of limestone on a mountaintop at about 7,000 feet [2,130 meters],” McGovern said. The remote area includes the important Neolithic site of Çayönü. From this and other archaeological digs, McGovern collected pottery and stone fragments to test for ancient organic material—perhaps the residue of long-evaporated, locally produced wine.” */

“McGovern’s current focus on eastern Turkey reflects his hypothesis that grape domestication, and its attendant wine culture, began in a specific region and spread across the ancient world.He calls it the Noah Hypothesis, as it suggests a single locality for an ancestor grape, much as the Eve Hypothesis claims that human ancestry can be genetically traced to a single African mother. In the Bible, Noah landed on the slopes of Mount Ararat (in what is now eastern Turkey) after the Flood. He is described as immediately planting grapevines and making wine. */

“Neolithic eastern and southeastern Turkey seems to have been fertile ground for the birth of agriculture. “Einkorn wheat appears to have been domesticated there, one of the so-called Neolithic founder plants—the original domesticated plants that led to people settling down and building towns,” McGovern explained. “So all the pieces are there for early domestication of the grape.” */

World’s Oldest and Largest Wine Cellar Found in Israel

In 2014, archaeologists in Israel announced that a palace at they were have excavating in the Canaanite fortress of Tel Kabri contained what they described as the world's oldest and largest personal wine cellar. Kimberly Ruble wrote in The Guardian: “The Middle Bronze Age palace, which was built during 1900 B.C. to 1600 B.C., covers a massive 200 acres in the northwestern region of modern-day Israel.” The team of scientists that found it claim it was so splendid” even the most magnificent of wine connoisseurs would be jealous.” [Source: Kimberly Ruble, The Guardian, September 25, 2014 ]

“Archaeologist Andrew Koh told the media that what was so fascinating about the wine cellar besides its size was that it was part of a household economy. It was the owner’s private wine vault and the wine was never intended to be given away as part of any system of providing for the public. It was only for his personal enjoyment and the support of his power. So basically, even though despite the details that it might have been the biggest and oldest wine cellar found to the present date in the Middle East, it was used strictly for private pleasure, and not for any commercial storing. “A research report recently printed up in the science journal PLoS ONE, explained how Dr. Koh and his team unearthed the huge room located just to the west of the palace’s central courtyard. It was full of gigantic, but slender necked vessels that were believed to have held the wine. Three of the over 40 jars discovered were carefully examined and researchers found trace amounts of tartaric acid, which is one of the key acids found in wine. They also discovered syringic acid, which is a mixture linked to red wine specifically, and remains from herbs, tree resign, and even honey – all various additives to wine.

“Dr. Koh explained that if the wine was still intact, he and his team would have been able to taste a fairly refined drink. Someone was actually sitting there and the person had years if not generations of experience behind him saying that these items are what best preserves the wine and gives it a better taste. It is something amazing to think about when a modern day person actually takes the time to dwell on it. He was asked about how much wine was really in the cellar. The wine vessels were entirely of uniform size and stored just under 530 gallons of alcohol, according to preliminary reports that were presented at the yearly meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research which occurred in November of 2013. That would be the equal to around 3,000 modern day bottles of wine.”

What Wine from World’s Oldest Wine Cellar May Have Tasted Like

Palace at Tel Kabri

Over a period of six weeks, the team excavating the ruined palace in Tel Kabri, Israel found 40 jugs, each one just over three feet tall, that once held 3,700-year-old wine according to findings presented today at the annual meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Megan Garber wrote in The Atlantic: “The liquid contents of the jars, alas, have not survived. So how did the researchers know they were wine jugs, and not some other vessel? The team, composed of scientists from George Washington University, Brandeis University, and Tel Aviv University (and who, it's worth noting, have yet to publish their findings in a peer-reviewed journal) analyzed the organic residues trapped in the pores of the jars. [Source: Megan Garber, The Atlantic, November 22, 2013, Wall Street Journal via Gizmodo +++]

“Emphasizing pottery fragments collected from the bases of the jars, which would have been guaranteed to have had contact with whatever was stored inside them, the team analyzed the chemical components of the residues. They found, among other things, tartaric acid, which is a key component in grapes. They found traces of other compounds, too, suggesting ingredients that would have been added to the wine—among them honey, mint, and other herbs. +++

“So ... minty wine? Herby wine? Really, really well-aged wine? What exactly would that have tasted like? "Sweet, strong and medicinal," the Wall Street Journal says—and "certainly not your average Beaujolais." The herbaceous booze was, in fact, probably much more akin to cough syrup (or maybe to cough syrup laced with sherry) than it would be to our current, smooth-drinking concoctions. The combination of grape with honey and herbs, the researchers note, makes the Kabri wines similar in makeup to wines that were drunk, seemingly for medicinal purposes, for 2,000 years in ancient Egypt. (The Kabri wines would have been both white and red, researchers told the Journal.) And those wines, in turn, match textual descriptions of the wines of Mesopotamia.

French Wine 'Has Italian Origins'

The earliest evidence winemaking in France appears to indicate it has Italian origins. A team led by Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum examined amphoras from various places to track how winemaking evolved and spread through the Middle East and Europe. Jason Palmer wrote for the BBC: “The Etruscans, a pre-Roman civilisation in Italy, are thought to have gained wine culture from the Phoenicians - who spread throughout the Mediterranean from the early Iron Age onward - because they used similarly shaped amphoras. Further, it is known that the Etruscans shipped goods to southern France in these amphoras- but until now it remained unclear if they held wine or other goods.”[Source: Jason Palmer, BBC News, June 3, 2013 |::|]

“Dr McGovern and colleagues have pinned down another part of the story in a study appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.. "You could argue that it comes [into France from] farther north on the continent," he told BBC News. "You could have it spreading across Germany, say, from Romania - but this really provides a definite set of evidence that it came from Italy." |::|

“Dr McGovern's team focused on the coastal site of Lattara, near the town of Lattes south of Montpellier, where the importation of amphoras continued up until the period 525-475 B.C. They used a high-precision analytical tool called gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, which provides a list of the molecules absorbed into the pottery of the amphoras. The results showed that they did once contain wine - as well as pine resin and herbal components. |::|

“But more surprising was the find of a wine-pressing platform, where grapes were ground and liquid drained off. "In a walled town like this, it is unusual to find a wine press from an early period," Dr McGovern said. "Finding the chemical evidence for the press, that was a surprise." The find is consistent with a pattern seen elsewhere - that wine is introduced from abroad, but a local culture eventually seeks to transplant the grapes and grow their own, local wine industry. "From there, [winemaking] spread up the Rhone River, the domesticated vine gets transplanted, it crosses with the wild grapes and all sorts of interesting cultivars develop - those are the ones that spread around the world. "Most of the wine we have today is from French cultivars, which ultimately derive from the Near-East cultivar via the Etruscans," he explained. "There's still a lot of blanks to fill in, but I find it very exciting." |::|

“The methods used in the study have pushed the boundaries of what can be gathered chemically from archaeological remains such as those in Lattara. Regis Gougeon of the University Institute of Vine and Wine at the University of Bourgogne said the work was "undoubtedly a good example of technology and methodology leading the science. It was already acknowledged - in particular thanks to Patrick McGovern's work - that viniculture might have travelled from the Near East to the Mediterranean Sea area about 3000 B.C. However, this Etruscan hypothesis is indeed rather new and sheds an interesting light on the possible input of this educated and art-oriented civilisation."” |::|

Later Wine History

The Greeks and Romans loved wine so much they created the gods Dionysus and Bacchus to honor it. Historians believe that wine was introduced to France (Gaul) by the Romans. Roman wine was generally thick syrupy stuff stored in amphorae and mixed with water — at a ratio of two to one or three to one — before it was consumed. In Roman times the best French wine came from Béziers. The native drink of Gaul was cervoise, a beer-like drink made from grain.

It the late 2000s Christopher Howe of Cambridge University and John Hager of Stanford University published a genetic study in which they showed that the original source of most of the strains of grapes used winemaking — such as Chardonnay, the source of Chablis, and gamay noir, the primary grape used to make Beaujolais — is the gouias blanc grape, a sour grape once so loathed by European aristocrats it was banned from winemaking. Both gouais blanc and pinot noir grapes were grown in the Middle Ages, with the former generally used to make poor quality wines and the latter used in high quality ones.

Phyloxeria, an American louse accidentally introduced to Europe in the 1860s, brought the European wine industry to its knees. Ironically the pest only attacked European roots. To save their wineries European vintners all over the continent grafted American roots onto their European vines. During this period French winemakers from Bordeaux, where grape crops were devastated, moved south to Rioja, Spain and other places, and founded wine industries there.

The year 1921 was one of the best vintage years. Top quality wine from all the world were produced that year.

See Bronze Age, Greeks, Romans, Middle Ages

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Georgia clay jar, researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024