DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE

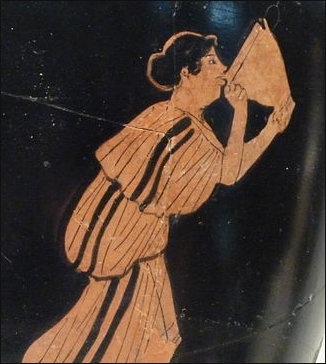

image from a vase of a woman drinking

The only drinks that were available to the Greeks in antiquity were water, wine, milk, and fruit juice. The Greeks preferred to drink from small, shallow cups rather than large and deep ones. Chilled fruit juices, milk and honey were enjoyed in the time of Alexander the Great (4th century B.C.). Rites of passage included giving three-year-old children their first jug, from which they had their first taste of wine.

Wine was far and away the main alcoholic drink. It was consumed with meals and at parties, regarded as sources of good conversation and extolled in poems and songs. Grape juice became wine quickly because there was no refrigeration or preservatives in ancient times.

The Greeks drank a lot wine but associated drunkenness with overindulgence and lack of discipline. According to their custom the Greeks mixed five parts water and two parts wine and sometimes added honey and salt water as flavoring. The Greeks believed that drinking undiluted wine could cause blindness, insanity or other terrible things. Later the Franks popularized the custom of drinking wine straight.

For hangover remedy, the forth century B.C. poet Amphis recommended boiled cabbage. An Ancient Greek spell for being able to drink a lot and not get drunk was to “eat a baked Pig's Lung.” [Papyri Graecae Magicae VII.181] |+|

Beer was by no means unknown to antiquity; in Egypt, Spain, Gaul, Thrace, etc., they brewed a malt liquor which must have had some resemblance to our beer, but the Greeks disliked this drink, and always spoke of it contemptuously. The gift of Dionysus remained the national drink of the Greeks, but it differed in many respects from our wines of the present day.

Websites on Ancient Greece:

Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Lives and Social Culture of Ancient Greece, Maryville University online.maryville.edu ;

BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; ; Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk;

Illustrated Greek History, Dr. Janice Siegel, Hampden–Sydney College hsc.edu/drjclassics ; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Ancient Greek Sites on the Web from Medea showgate.com/medea ; Greek History Course from Reed web.archive.org;

Classics FAQ MIT classics.mit.edu

See Separate Article:

ORIGIN OF ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST WINES, WINEMAKING, WINERIES AND WINE GRAPES factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com ;

DRINKS IN MESOPOTAMIA: MAINLY BEER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DRINKS: BEER, WINE, MILK AND WATER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKS AND DRUGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Intoxication in the Ancient Greek and Roman World” by Alan Sumler (2023) Amazon.com;

“Food and Drink in Antiquity: A Sourcebook: Readings from the Graeco-Roman World” (Bloomsbury Sources in Ancient History) by John F. Donahue (2015) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Greece and Cyprus: Production, Trade and Social Significance”

by Evi Margaritis, Jane M. Renfrew, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Courtesans & Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens” by James Davidson (1997) Amazon.com;

“Drinking Wine with Homer & the Earliest Greeks: Cultivating, Serving & Delighting in Ancient Greek Wine” by Tim J. Young Amazon.com;

“Houses of Ill Repute: The Archaeology of Brothels, Houses, and Taverns in the Greek World” by Allison Glazebrook and Barbara Tsakirgis (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Last of the Wine” by Mary Renault (1956), Novel Amazon.com;

“Symposium (Oxford World's Classics) by Plato Amazon.com;

“The Symposium in Context: Pottery from a Late Archaic House near the Athenian Agora” by Kathleen M. Lynch (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Symposion in Ancient Greek Society and Thought” (Reprint Edition)

by Fiona Hobden Amazon.com;

“The Deipnosophists” (Banquet of the Learned) Vol. 1 by Naucratis Athenaeus, written about A.D. 200, Amazon.com;

“Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton Science Library)

by Patrick E. McGovern (2019) Amazon.com;

“Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages”

by Patrick E. McGovern (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine Grapes: A Complete Guide to 1,368 Vine Varieties, Including Their Origins and Flavours” by Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding, et al. (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Ancient History of Wine: Food and Nutrition in History and Antropology” by Patrick E. McGovern, Stuart J. Fleming, et al. (2015) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Ancient Greeks” (The Greenwood Press Daily Life Through History Series) by Robert Garland (2008), Amazon.com;

“The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” (Classic Reprint) by Alice Zimmern (1855-1939) Amazon.com;

“The Greeks: Life and Customs” by E. Guhl and W. Koner (2009) Amazon.com;

“The Life of the Ancient Greeks, With Special Reference to Athens”

by Charles Burton (1868-1962) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Life in Ancient Greece” by Leslie Adkins and Roy Adkins (1998) Amazon.com;

Wine in Ancient Greece

In the “Odyssey,” Homer wrote: "and a herald, going back and forth, poured the wine for them" and "grape cluster after grape cluster" (Lattimore 1965:143, 121). Wine is mentioned over ten times in The Odyssey, mostly in relation to feasts or religious ceremonies of some sort. In these ceremonies, the men drank wine in moderation and only when mixed and consumed with the food [Source: Matthew Maher, University of Western Ontario, The Odyssey of Ancient Greek Diet, Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Issue 1, Article 3, June 19, 2011]

8th century Corinthian skyphos (wine-drinking cup)

Matthew Maher of the University of Western Ontario wrote: “Excavations on the island of Crete have provided archaeologists with many clues regarding the making, storage, and consumption of wine. There they have found residues in jars that indicate that they had once contained liquids, most likely olive oil or wine. On the mainland in the ancient city of Tiryns, the only physical remains of food discovered have been grape seeds. Because of the large quantity of seeds, it is assumed that they were used in the production of wine (Vickery 1936). Further evidence of the use of grapes in making wine is furnished by a discovery made by British archaeologists near Sparta, where they found a seal from the mouth of a jar. The clay imprints clearly show that it had been covered with leaves that have been identified as grape leaves (Vickery 1936). Although this doesn't prove the presence of wine, the evidence of grape leaves in this context certainly allows for that possibility.

“Another place to look for evidence of the presence of wine is pottery. Sometimes the shape of a pottery vessel can indictate its function. For example, the rhyton is a ritual pouring vessel that sometimes appeared in the shape of an animal head and is believed to have been used to pour wine (Pedley 1993). There are numerous examples of these types of vessels; specifically, a rhyton in the shape of a bull's head from Crete and one showing a hilltop sanctuary from the city of Zakro (Pedley 1993).

Evidence 6,200-Year-Old Wine Found In Greece: Oldest In Europe

In 2013, researchers working at the Dikili Tash site, two kilometers from the ancient city of Philippi an announced that chemical analysis of residues found on ceramics showed evidence of wine dating back to 4200 B.C.. The site has been inhabited since 6500 B.C., according to the researchers’ website. Dimitra Malamidou, a co-director of the excavation, told The Huffington Post, “All [that] is left from the liquid part is the residue in the surface of the ceramic vases,” she said. “Recent residue analysis on ceramics attested [to] the presence of tartaric acid, indicating fermentation.”[Source: Meredith Bennett Smith, Huffington Post, October 3, 2013 +++]

Meredith Bennett Smith wrote in Huffington Post: “Malamidou is part of a joint Greek-French excavation that began in 2008. The team recently wrapped up excavation of a neolithic house from around 4500 B.C. This is where they found wine traces in the form of “some thousands of carbonized grape pips together with the skins indicating grape pressing,” Malamidou said. Radiocarbon dating was used to pinpoint the age of the finds. +++

“Dikili Tash researchers believe they have found the oldest known traces of wine in Europe. Previous studies have unearthed a 6,100-year-old Armenian winery, as well as traces of a 9,000-year-old Chinese alcohol made from rice, honey and fruit. “The find is highly significant for the European prehistory, because it is for the moment the oldest indication for vinification in Europe,” Malamidou said. “The historical meaning of our discovery is important for the Aegean and the European prehistory, as it gives evidence of early developments of the agricultural and diet practices, affecting social processes.”“ +++

Wine Introduced to France by Ancient Greeks, Cambridge Study Says

krater, used for mixing water with wine

A study by Prof Paul Cartledge of Cambridge University suggests that wine was introduced to France by a “band of pioneering Greek explorers” who settled in southern France around 600 B.C. The study debunks theories that the Romans brought viticulture to France. The study suggests the introduction took place at Massalia, present-day Marseilles, which the Greeks founded and turned into a trading site, where they traded with local tribes such as the Ligurian Celts. [Source: Andrew Hough, Telegraph.co.uk, October 23, 2009 -]

Andrew Hough wrote in the Telegraph: “Prof Cartledge said within a matter of generations the nearby Rhône became a major thoroughfare for vessels carrying terracotta amphorae that contained what was seen as a new, exotic Greek drink made from fermented grape juice. He argued the new drink rapidly became a hit among the tribes of Western Europe, which then contributed to the French’s modern love of wine. “I hope this will lay to rest an enduring debate about the historic origins of supermarket plonk,” he said. -

“Although some academics agree the Greeks were central to founding Europe’s wine trade, others argue the Etruscans or even the later Romans were the ones responsible for bringing viticulture to France.” Archaeologists have discovered a five-foot high, 31.5 stone bronze vessel, the Vix Krater, which was found in the grave of a Celtic princess in northern Burgundy, France. -

“Prof Cartledge said there were two main points that proved it was the Greeks who introduced wine to the region. First, the Greeks had to marry and mix with the local Ligurians to ensure that Massalia survived, suggesting that they also swapped goods and ideas. Second, they left behind copious amounts of archaeological evidence of their wine trade (unlike the Etruscans and long before the Romans), much of which has been found on Celtic sites.” The research forms part of Professor Cartledge’s study into where the boundaries of Ancient Greece began and ended. Rather than covering the geographical area occupied by the modern Greek state, he argued Ancient Greece stretched from Georgia in the east to Spain in the west.” -

Early Wine

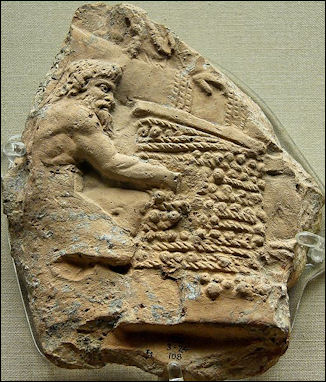

Greek satyr's wine press Intentional wine-making is believed to have begun in the Neolithic period (from about 9500 to 6000 B.C.) when communities settled in year-round settlements and began intentionally crushing and fermenting grapes and tending a grape crop year round. This is believed to have first occurred in Transcaucasus, eastern Turkey or northwestern Iran. Around the same time the Chinese were making wines with rice and local plant food.

Grapes contains a lot of sugar. Fermentation caused by the addition of yeast turns toe sugar into alcohol. Yeats is very common, Wild grapes often have some present on their skins, probably transported by wasps or other flying insects. Without distillation, the highest alcohol content is 5 percent for beer and 11 to 12 percent for wine. Above these levels the yeasts lo longer produce fermentation.

Stone Age people drank fermented wine by accident and probably made by accident too. The first people who drank alcohol probably eaten a fruit that fell off a tree and naturally fermented. Elephants sometimes get loaded by eating fermented fruit. Grapes sometimes ferment right on the vine. Birds who have gotten so drunk from eating sch grapes they have fallen off their perches.

Wine is believed to have been tasted by Paleolithic men who ate grapes with juice that had fermented within the grape skins during years that occurs naturally on the skins. They then might have made wine in containers that had to be drunk quickly, like Beaujolais Nouveau, before it turned to wine.

See Separate Articles FIRST WINES, WINERIES AND ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ; EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com

Wine Drinking in Ancient Greek

The customary drink at feasts and symposia was a mixture of wine and water. Even at the present day southern nations seldom drink strong wine unmixed with water, and in ancient times unmixed wine was only drunk in very small quantities; at the symposium, when it was customary to drink deep and long, they had only mixed wine, sometimes taking equal parts of wine and water, and sometimes, which was even commoner, three parts of water to two parts of wine.

Francisco Javier Murcia wrote in National Geographic History: In Classical Greece, wine was aged in leather and clay containers, which gave it an acidic taste and raised the alcohol content to a very potent 16 percent. Mixing the wine with water weakened it and made it much less bitter. According to myth, it was the god Dionysus who taught King Amphictyon of Athens to dilute wine in this way. Drinking straight wine was seen as uncivilized, the kind of behavior their barbaric neighbors would indulge in. The Greeks called the practice “drinking Scythian-style.” They believed that drinking undiluted wine was not only uncouth, but that the practice was also unsafe, potentially leading to madness. [Source: Francisco Javier Murcia, National Geographic History, January-February 2017]

The Greeks did not drink pure wine. It was first mixed with water in the krater before being served in the communal cup. Generally speaking, the mixture was two parts wine to five parts water, or one part wine to three parts water. The dilution was a nod to moderation: It lengthened the evening’s pleasure by ensuring the guests would be truly intoxicated only at the end of the night. Wine was sometimes mixed in a special vessel, a psykter, filled with cold water or even snow, to chill the drink. Usually a single cup was passed among the guests from left to right, and a young slave filled the krater each time. During the symposium guests nibbled on snacks called tragemata — dried fruit, toasted beans, or chickpeas — which both absorbed the alcohol and built up a thirst for more.

Generally, at the beginning of every symposium, a president, or “Symposiarch,” was appointed by lot or dice to take command for the rest of the evening, and it was his duty to determine the strength of the mixture, for this might be of various kinds, as weak even as two parts of wine to five of water, or one to three, or even one part of wine to five of water, which last was certainly a somewhat tasteless drink, and was contemptuously called “frog’s wine.” In early times it was usual to put the water first into the mixing bowl and pour the wine upon it; afterwards the reverse proceeding took place.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

Men used to hang out at wine shops where strong syrupy wine was poured from an amphorae and diluted with water in a large mixing bowl. Rich Greeks and Romans chilled their wine with snow kept in straw lined pits, even though Hippocrates thought that "drinking out of ice" was unhealthy.

Types of Wine in Ancient Greece

Much of the ancient wine must have resembled in taste the resin wine of modern Egypt, since resin was added to it, and as the large clay casks in which the wine was exported were painted over internally with pitch, this must of necessity have given a taste to the wine. Nor did they know how to clear their wine; it was usually thick, and, in order to be made at all bright, had to be filtered through a fine sieve or cloth each time before it was used. [Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The wine from Kos was good and relatively inexpensive. Higher quality wines came from Rhodes, Lesbos and Chios. Thasian wines were also largely exported. Artemidorus described a drink called “ melogion” which "is more intoxicating than wine" and "made by first boiling some honey with water and then adding a bit of herb." Homer described a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey and goat cheese. The commoner sorts of wine were very cheap, and in consequence it was the universal drink, of which even the poor people and slaves partook.

Wine Drinking Reflected in Ancient Greek Art and Crafts

There are numerous amphora reliefs showing the consumption of wine. A black-figure amphora from Attica, dated to approximately 500 B.C., shows Dionysus, the god of wine, consuming his drink from a large cup.

An amusing 2,400-year-old mosaic discovered in southern Turkey, discovered in 2012, depicts a skeleton reclining with a pitcher of wine and loaf of bread alongside Greek text that reads, "Be cheerful, enjoy your life." Archaeologist Demet Kara told Daily Sabah that the mosaic was located in the dining room of an upper class house from the 3rd century B.C. While a similar mosaics has been seen in Italy, the cheerful skeleton is the first of its kind to have been found in Turkey.,[Source: Jeva Lange , The Week, April 23, 2016]

After the turn of the 6th century B.C., changes in drinking cups correlated with Athens’ rising political power and rising dominance in the ceramic market. There was great variety and black-figured pottery production during this period. Stemmed cups were probably because they were easier to hold while reclining. The middle of the 6th century B.C. saw a rapid proliferation of cup types: Komast cups, Siana cups, Gordion cups, Lip cups, Band cups, Droop cups, Merry-thought cups and Cassel cups. Some were popular for only a few decades. During period of the devastating Persian Wars, the proliferation of cup types declined, with red-figured drinking cups, being introduced around 525 B.C., and quickly becoming the most popular. [Source: sciencedaily.com, January 2011]

Red-figured cups (cups decorated with red figures vs. black) were popular in the High Classical Period (480-400 B.C.), with the cups growing taller and shallower over time. During period of the Peloponnesian Wars and plague, drinking cup fashions came and went with lasting very long. , but few developed into long-lived styles. Terra-cotta “designer knock-offs” — plain, black clay cups with shiny surfaces and delicate stamped and incised designs — of “high-end” silver cups were common. During the Late Classical Period (400-323 B.C.) designer knock-off drinking cups continued; however, the variety of these “silver-inspired” clay cup designs declined with impractical designs like high-swung handles that served no useful purpose in clay falling out of fashion. The same was true with the tradition of decorating cups with human figures. A decorative innovation, called West Slope, became popular at this time. It consisted of colored clay applied atop black-glazed surfaces to create the effects of garlands and wreaths.

Hellenistic drinking scene

Symposiums and Ancient Greek Drinking Customs

A symposium was a dinner party with family, friends or associates. It generally began with a bout of drinking, followed by a big meal. There were often rules to ensure equality. Men participating in symposia, generally drank the same amount of wine mixed with water, served in rounds, as they reclined on couches or mattresses set in a circle or square. Conversation topics included philosophy, politics, gossip. For a short period Greeks used birthday cakes.

The word symposia was used to describe the party and the place were it was held and is the source of the modern word symposium. The parties were usually lead by a feast master. Sometimes the guests wore garlands. Some people drank heavily; others held back.

There are vivid description of party entertainment in Xenophon's dialogue Symposium (380 B.C.). The host pays a man from Syracuse to bring traveling performers (probably slaves), a girl flutists, acrobats, a dancing girl and a boy who dances and plays the kithara , a kind of lyre. The group played music and did performances involving music, dance, acrobatics and mine. The girl juggled hoops, performed acrobatic stunts over a hoop rimmed with knives, and acted out mythical love scenes with the boy. Socrates, one of the guests, was quite taken with the boy. The citizens of Sybaris in present-day southern Italy were such big partiers they reportedly banned roosters so the populous would not be woken to early in the morning. They also supposedly had wine piped directly from the vineyards to the city.

See Separate Article: SYMPOSIUM IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com

Wine Cups Show Changes In Ancient Greek Drinking Habits

Wine cups used during social gatherings, called symposia, reflect changes in ancient Greek drinking habits according to Lynch, the University of Cincinnati professor. “In the same way that the coffee mug with ‘World’s Greatest Golfer’ in your kitchen cabinet speaks to your values and your culture, so, too, do the commonly used objects of the past tell us about that past,” she said. [Source: Wynne Perry, Lives Science, January 2011 /*/]

Wynne Perry of Lives Science wrote: “As the social context went full circle from elite party to common practice and back again, the appearance of the cups evolved as well, from simple and stemless to a profusion of styles to knockoffs that imitated the appearance of silverwork. During the Iron Age, from 1,100 to 700 B.C., the symposia were reserved for the elite, and grave markers for the very wealthy were even made to resemble the mixing bowls used to blend wine and water during the symposia. People wanted to be remembered by their ability to throw these events, according to Lynch.

19th century vision of a Greek wine festival

“In the latter part of the late Archaic Period, from 525 to 480 B.C., the number of drinking cups increased, indicating the democratization of the cocktail parties, a phenomenon also occurring in the political and social arenas. In fact, these cups for communal drinking outnumbered regular dishes in the typical home. Lynch said, “Possessing what was newest in terms of mode and style of drinking cups was likely equated with knowledge and status. The elites may have been seeking cohesion and self definition in the face of factional rivalries and populist movements. This hypothesis underscores how the drinking symposia — and specific cup forms identified with specific factions — might have been used by aristocratic blocs to cement group bonds in the politically charged environment of the time.” [Source: sciencedaily.com, January 2011]

“During the High Classical Period from 480 to 400 B.C., the evolution in design continued, with red-figured cups remaining popular at first, but becoming taller and shallower. As Athenians weathered the Peloponnesian Wars and the plague, they sought escape, and drinking-cup fashions came and went. However, they tended to imitate silverwork: For example, plain, black clay cups with shiny surfaces became more common. Essentially, the common terra cotta cups were “designer knockoffs,” according to Lynch.

“This knockoff trend continued into the Late Classical Period, from 400 to 323 B.C., and garland and wreathlike designs replaced human forms as decoration. Athenian democracy disappeared, and by the end of this period, the practice of the symposia had returned to the elites. Equality was no longer important in a state that was now a monarchy, according to Lynch.” /*/

Kottabos, an Ancient Greek Drinking Game

“Kottabos” is one of the world first known drinking games. A fixture of ancient Greek symposiums and all-night parties and reportedly even played by Socrates, the game involved flinging the dregs left over from a cup of wine at a target. Usually the participants sat in a circle and tossed their dregs at the basin in the center. The game was so popular that ancient Greeks built special round rooms where it the game could be played, so all competitors were equidistant from the target. It has been suggested that after centuries of being played it died out because it was such a mess to clean up afterwards.

Kottobos is said to have been introduced from Sicily. Critias, the 5th century academic and writer, wrote about this “glorious invention” stemming from Sicily, “where we put up a target to shoot at with drops from our wine-cup whenever we drink it.” While a handful of modern academics question the game’s Sicilian origins, kottabos definitely spread throughout parts of Italy (as the Etruscans played it) and Greece, too. It fell into disuse during the age of Alexander’s successors, and was unknown to the Romans.

Megan Gannon wrote in Live Science, “At Greek symposia, elite men, young and old, reclined on cushioned couches that lined the walls of the andron, the men’s quarters of a household. They had lively conversations and recited poetry. They were entertained by dancers, flute girls and courtesans. They got drunk on wine, and in the name of competition, they hurled their dregs at a target in the center of the room to win prizes like eggs, pastries and sexual favors. Slaves cleaned up the mess. [Source: Megan Gannon, Live Science, January 14, 2015]

See Separate Article: GAMES IN ANCIENT GREECE: KOTTABOS, KID'S TOYS, GAMBLING europe.factsanddetails.com

grape crushing

Drunkenness in Ancient Greece

In spite of the custom of mixing the wine with water, the great quantities consumed, since drinking went on far into the night, did often conduce to drunkenness. A vase painting shows us the immediate consequences of excessive drinking: we see a youth vomiting his wine, while a pretty girl is smiling and holding his head.[Source “The Home Life of the Ancient Greeks” by Hugo Blümner, translated by Alice Zimmern, 1895]

The official termination of the symposium was a libation to Hermes, but even then they did not always set out on their homeward journey in company with the slaves who were waiting for their masters with torches or lanterns, but sometimes their excitement led them to wander noisily through the streets with the flute girls and torch bearers in a Comus, and they thus entered the houses of friends who were still sitting at their wine, or carried on all manner of jokes and absurdities. This naturally led to other scenes, such as fighting, etc., especially if one of the participants tried to obtain entrance to an hetaera, when a quarrel often ensued between the rivals.

A vase painting represents a scene from the Comus, the chief person in which is the drunken Hercules, accompanied by satyrs, but in reality it is only a scene from real life transported to the heroic domain. The hero, who is lying dead drunk on the ground, appears to have demanded admittance at a door which remained closed to him, and some old woman has poured water upon him from a window over the doorway. Two young satyrs, adorned with fillets and wreaths, of whom one bears a thyrsus and a basket of fruit and cakes, the other a mixing-bowl and fillets, and a harp girl with a thyrsus wand, and a flute player with a torch, are the attendants of this night wanderer. These scenes furnish an unpleasant contrast to the conclusion of the Platonic Symposium, when Socrates, who has been drinking hard all night, but at the same time carrying on serious conversation with some friends as staunch as himself, gets up at daybreak, while the rest of the participants have fallen fast asleep, walks with steady step to the well in the Lyceum, and then, as usual, proceeds to his day’s occupations.

Bronze Age Beer Found in Greece

The ancient Greeks may have loved their wine but that's wasn’t the only alcoholic beverage they drank. In 2018, Archaeologists from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki announced they had located several archaeobotanical remains of a cereal that could have been used in beer brewing in the Archontiko area on the island of Corfu in northern Greece, and in Argissa in Zakynthos further south and to the east. At Archontiko, archaeologists found about 100 individual cereal seeds dating back to the early Bronze Age from 2100 to 2000 B.C. In Argissa, they found about 3,500 cereal seeds going back to the Bronze Age, approximately from 2100 to 1700 B.C.. [Source Tornos News, June 26, 2018]

Tornos News reported: Moreover, archaeologists discovered a two-room structure that seems to have been carefully constructed to maintain low temperatures in the Archontiko area, suggesting it was used to process the cereals for beer under the right conditions. This discovery is the earliest known evidence of beer consumption in Greece, but not in the planet. Beer is one of the oldest beverages humans have produced, dating back to at least the 5th millennium B.C. in Iran, and was recorded in the written history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia and spread throughout the world.

In the case of Archontiko, along with rich cereal residues, a concentration of germinated cereal grains, ground cereal masses and fragments of milled cereals were found inside the remains of two houses. Their condition is put down to malting and charring, claim researchers. The practice of brewing could have reached the Aegean region and northern Greece through contacts with the eastern Mediterranean where it was widespread, it is also suggested.

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science, The "stout" discoveries mark what may be the oldest beer-making facilities in Greece and upend the notion that the region's ancient go-to drink was only wine, the researchers said. "It is an unexpected find for Greece, because until now all evidence pointed to wine," study researcher Tania Valamoti, an associate professor of archaeology at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in Greece, told Live Science. The finding hints that prehistoric Greeks were "using alcoholic drinks for feasts all year-round, instead of just on a seasonal basis," when grapes were ripe, Brian Hayden, a professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University, in British Columbia, Canada, who wasn't involved with the study, told Live Science. [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, February 1, 2018]

The discovery of sprouted cereal grains is significant: To make beer, a brewer sprouts cereal grains (a process known as malting), which changes the grain's starch into sugars. This sprouting process is then interrupted by roasting the grain. Next, the grains are coarsely ground and mixed with lukewarm water to make wort, which helps convert the remaining starches into sugars. Finally, during alcoholic fermentation, "the sugars in the malt are used by yeast, which is present in the air or introduced with grapes or from other sources," Valamoti wrote in the study. "I'm 95 percent sure that they were making some form of beer," Valamoti said. "Not the beer we know today, but some form of beer."

The two-chambered structure at Archondiko "seems to have been carefully constructed to maintain low temperatures in the rear chamber, possibly even below 100 degrees Celsius [212 degrees Fahrenheit]," Valamoti wrote in the study. Given that a temperature of 158 degrees F (70 degrees C) is ideal for preparing the mash and wort, it's possible that ancient people used this structure during the beer-making process, she said. There were even special cups — 30 at Archondiko and 45 in the Agrisso house — near the sprouted grains, suggesting they may have been used to serve beer. However, the Archondiko cups were difficult to drink from, so it's possible that thirsty people there sipped beer through straws, Valamoti said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Greece sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Hellenistic World sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Greeks bbc.co.uk/history/; Canadian Museum of History, Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; MIT Classics Online classics.mit.edu ; Gutenberg.org, Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Live Science, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Encyclopædia Britannica, "The Discoverers" and "The Creators" by Daniel Boorstin. "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024