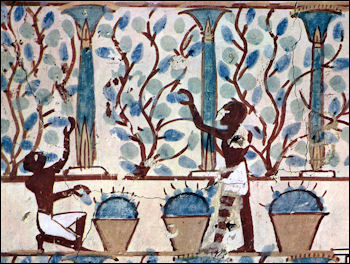

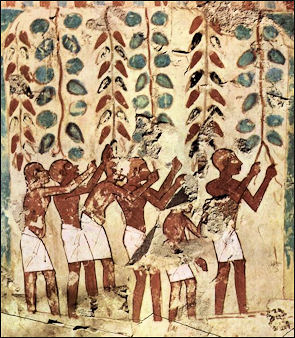

EARLY WINE AND ALCOHOLIC DRINKS

collecting grapes in ancient Egypt Grapes contains a lot of sugar. Fermentation caused by the addition of yeast turns to sugar into alcohol. Yeast is very common, Wild grapes often have some present on their skins, probably transported by wasps or other flying insects. Without distillation, the highest alcohol content is 5 percent for beer and 11 to 12 percent for wine. Above these levels the yeasts lo longer produce fermentation.

Wine is believed to have been consumed by Paleolithic humans who ate grapes with juice that had fermented within their grape skins by yeasts that occur naturally on the skins. They then might have made wine in containers that had to be drunk quickly, like Beaujolais Nouveau, before it turned to vinegar. Honey was plentiful and could easily have been turned into mead.

According to Archaeology magazine: The happy accident of biting into a piece of fruit or sipping liquid imbued with the intoxicating properties imparted by fermentation must have beguiled innumerable early humans and their ancestors. At what point, however, did they first seek to control the process of alcoholic fermentation? A lump of beeswax wrapped in plant material and tied with twine discovered in South Africa’s Border Cave in 2012 suggests that early hunter-gatherers may have been making a type of honey-based alcohol there as long as 40,000 years ago. The bundle also contained traces of a protein substance, possibly egg, and tree resin — a recipe lost to time. This possible progenitor of a type of mead that is still made by the nomadic San peoples of South Africa may have been among a variety of new foods and technologies produced during the Paleolithic period. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

According to the University of Pennsylvania’s “Origins and History of Ancient Wine”: Fermented beverages have been preferred over water throughout the ages: they are safer, provide psychotropic effects, and are more nutritious. Some have even said alcohol was the primary agent for the development of Western civilization, since more healthy individuals (even if inebriated much of the time) lived longer and had greater reproductive success. When humans became “civilized,” fermented beverages were right at the top of the list for other reasons as well: conspicuous display (the earliest Neolithic wine, which might be dubbed “Chateau Hajji Firuz,” was like showing off a bottle of Pétrus today); a social lubricant (early cities were even more congested than those of today); economy (the grapevine and wine tend to take over cultures, whether Greece, Italy, Spain, or California); trade and cross-cultural interactions (special wine-drinking ceremonies and drinking vessels set the stage for the broader exchange of ideas and technologies between cultures); and religion (wine is right at the center of Christianity and Judaism; Islam also had its “Bacchic” poets like Omar Khayyam). Whatever the reason, we continue to live out our past civilization by drinking wine made from a plant that has its origins in the ancient Near East. Your next bottle may not be a 7000 year old vintage from Hajji Firuz, but the grape remains ever popular—cloned over and over again from those ancient beginnings. [Source: Penn Museum]

“Fermentation needs fire and pottery,” wrote R.J. Forbes in his Studies in Ancient Technology volume III published in 1965. He goes on to say “the techniques of fermenting came with organized agriculture, some traces of which go back to the Upper Palaeolithic Period. These would have probably involved wild grasses, and then only when there was an excess of grain. Regular production of ferment cereal grains would have only come about in Neolithic times.” [Source: Joanna Linsley-Poe, 2011]

See Separate Articles:

EARLIEST WINES, WINEMAKING, WINERIES AND WINE GRAPES factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com ;

DRINKS IN MESOPOTAMIA: MAINLY BEER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DRINKS: BEER, WINE, MILK AND WATER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKING AND DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKS AND DRUGS IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/ ; Food Timeline, History of Food foodtimeline.org ; Food and History teacheroz.com/food

Accidental Discovery of Alcoholic Drinks

Stone Age people probably drank fermented wine by accident and probably made it by accident too. The first people who drank alcohol probably ate fruit that fell off a tree and naturally fermented. Elephants and monkeys sometimes get drunk by eating fermented fruit. Grapes sometimes ferment right on the vine. Birds have gotten so drunk from eating such grapes they have fallen off their perches.

William Cocke wrote in National Geographic News: “The first wine-tasting may have occurred when Paleolithic humans slurped the juice of naturally fermented wild grapes from animal-skin pouches or crude wooden bowls. The idea of winemaking may have occurred to our alert and resourceful ancestors when they observed birds gorging themselves silly on fermented fruit and decided to see what the buzz was all about. [Source: William Cocke, National Geographic News, July 21, 2004 */]

Frank Thadeusz wrote in Spiegel Online: “It turns out the fall of man probably didn’t begin with an apple. More likely, it was a handful of mushy figs that first led humankind astray. “Here is how the story likely began — a prehistoric human picked up some dropped fruit from the ground and popped it unsuspectingly into his or her mouth. The first effect was nothing more than an agreeably bittersweet flavor spreading across the palate. But as alcohol entered the bloodstream, the brain started sending out a new message — whatever that was, I want more of it! Humankind’s first encounters with alcohol in the form of fermented fruit probably occurred in just such an accidental fashion. But once they were familiar with the effect, archaeologist Patrick McGovern believes, humans stopped at nothing in their pursuit of frequent intoxication. [Source: Spiegel Online, By Frank Thadeusz, December 24, 2009 /~]

““The whole process is sort of magical,” Patrick McGovern, an expert on the origins of ancient wine and an expert in the field of biomolecular archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, told National Geographic News. “You could even call [fermentation] the first biotechnology.” */

Alcohol Consumption May Be 10 Million Years Old, Study Says

wild chimpanzees feeding on ficus fruit

A study published in 2014 suggests that primates may have begun drinking alcohol in the form of fermented fruit on the forest floor 10 million years ago. Sarah Knapton wrote in The Telegraph: “Alcohol was thought to have been first brewed by Neolithic farmers around 9,000 years ago when northern Chinese villagers made the happy discovery that fruit and honey could be fermented into an intoxicating liquor.But new evidence suggests our ancestors had become accustomed to drinking nearly 10 million years before. [Source: Sarah Knapton, The Telegraph, December 1, 2014 |||]

“Scientists now believe that when primates left the trees and began walking on two feet they also started scooping up mushy, fermented fruit which was lying on the ground. And over time their bodies learned to process the ethanol present. Experts at Santa Fe College in the US studied the gene ADH4 which produces an enzyme to break down alcohol in the body. It was hypothesised that the enzyme would not appear until the first alcohol was produced by early farmers. But scientists were amazed to find it 10 million years earlier, at the end of the Miocene epoch. |||

“The findings could explain why tree-dwelling orang-utans still cannot metabolize alcohol while humans, chimps and gorillas can. “This transition implies the genomes of modern human, chimpanzee and gorilla began adapting at least 10 million years ago to dietary ethanol present in fermenting fruit,” said Professor Matthew Carrigan, of Santa Fe College. “This conclusion contrasts with the relatively short amount of time – about 9,000 years – since fermentative technology enabled humans to consume beverages with higher ethanol content than fruit fermenting in the wild. Our ape ancestors gained a digestive enzyme capable of metabolizing ethanol near the time they began using the forest floor about 10 million years ago. Because fruit collected from the forest floor is expected to contain higher concentrations of fermenting yeast and ethanol than similar fruits hanging on trees this transition may also be the first time our ancestors were exposed to – and adapted to – substantial amounts of dietary ethanol.” |||

“Any primates unable to digest the fermented fruits would have died before passing on their genes, but those who could would have passed the drinking gene on to their offspring. The evolutionary history of the ADH4 gene was reconstructed using data from 28 different mammals, including 17 primates, collected from public databases or well-preserved tissue samples. |||

“The first evidence of man making alcohol comes from the Neolithic village Jiahu in China where clay pots were found containing residues of tartaric acid, one of the main acids present in wine. Some archaeologists have suggested that the entire Neolithic Revolution, which began about 11,000 years ago, was fuelled by the quest for by drinking and intoxication. Archaeologist Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania claims that prehistoric communities cultivated wheat, rice, corn, barley, and millet primarily for the purpose of producing alcoholic beverages. He believes that early farmers supplanted their diet with a nutritious hybrid swill which was half fruit and half wine.” |||

Was Agriculture Developed to Produce Alcohol?

Frank Thadeusz wrote in Spiegel Online: “Did our Neolithic ancestors turn to agriculture so that they could be sure of a tipple? US Archaeologist Patrick McGovern thinks so. The expert on identifying traces of alcohol in prehistoric sites reckons the thirst for a brew was enough of an incentive to start growing crops. “It turns out the fall of man probably didn’t begin with an apple. More likely, it was a handful of mushy figs that first led humankind astray. [Source: Spiegel Online, By Frank Thadeusz, December 24, 2009 /~]

“A secure supply of alcohol appears to have been part of the human community’s basic requirements much earlier than was long believed. As early as around 9,000 years ago, long before the invention of the wheel, inhabitants of the Neolithic village Jiahu in China were brewing a type of mead with an alcohol content of 10 percent, McGovern discovered recently. /~\

“Lacking any knowledge of chemistry, prehistoric humans eager for the intoxicating effects of alcohol apparently mixed clumps of rice with saliva in their mouths to break down the starches in the grain and convert them into malt sugar. These pioneering brewers would then spit the chewed up rice into their brew. Husks and yeasty foam floated on top of the liquid, so they used long straws to drink from narrow necked jugs. Alcohol is still consumed this way in some regions of China. [Source: Spiegel Online, By Frank Thadeusz, December 24, 2009 /~]

“McGovern sees this early fermentation process as a clever survival strategy. “Consuming high energy sugar and alcohol was a fabulous solution for surviving in a hostile environment with few natural resources,” he explains. The most recent finds from China are consistent with McGovern’s chain of evidence, which suggests that the craft of making alcohol spread rapidly to various locations around the world during the Neolithic period. Shamans and village alchemists mixed fruit, herbs, spices, and grains together in pots until they formed a drinkable concoction. /~\

“But that wasn’t enough for McGovern. He carried the theory much further, aiming at a complete reinterpretation of humanity’s history. His bold thesis, which he lays out in his book “Uncorking the Past. The Quest for Wine, Beer and Other Alcoholic Beverage,” states that agriculture — and with it the entire Neolithic Revolution, which began about 11,000 years ago — are ultimately results of the irrepressible impulse toward drinking and intoxication.

Neolithic Period: the Right Time to Begin Making Alcohol

Image of agriculture in ancient Egypt

According to the University of Pennsylvania’s “Origins and History of Ancient Wine”: “If winemaking is best understood as an intentional human activity rather than a seasonal happenstance, then the Neolithic period (8500-4000 B.C.) is the first time in human prehistory when the necessary preconditions for this momentous innovation came together. Most importantly, Neolithic communities of the ancient Near East and Egypt were permanent, year-round settlements made possible by domesticated plants and animals. With a more secure food supply than nomadic groups and with a more stable base of operations, a Neolithic “cuisine” emerged. [Source: Penn Museum]

Using a variety of food processing techniques—fermentation, soaking, heating, spicing—Neolithic peoples are credited with first producing bread, beer, and an array of meat and grain entrées we continue to enjoy today.

Crafts important in food preparation, storage, and serving advanced in tandem with the new cuisine. Of special significance is the appearance of pottery vessels around 6000 B.C. The plasticity of clay made it an ideal material for forming shapes such as narrow-mouthed vats and storage jars for producing and keeping wine After firing the clay to high temperatures, the resultant pottery is essentially indestructible, and its porous structure helps to absorb organics. A major step forward in our understanding of Neolithic winemaking came from the analysis of a yellowish residue inside a jar excavated by Mary M. Voigt at the site of Hajji Firuz Tepe in the northern Zagros Mountains of Iran. The jar, with a volume of about 9 liters (2.5 gallons) was found together with five similar jars embedded in the earthen floor along one wall of a “kitchen” of a Neolithic mudbrick building, dated to ca. 5400-5000 B.C. The structure, consisting of a large living room that may have doubled as a bedroom, the “kitchen,” and two storage rooms, might have accommodated an extended family. That the room in which the jars were found functioned as a kitchen was supported by the finding of numerous pottery vessels, which were probably used to prepare and cook foods, together with a fireplace.

Mead and Fruit Wine

Mead is an alcoholic drink made with honey. Mead or a mead-like drink dates back to 7000 B.C. and mainland China, where archeological digs have unearthed ancient pottery with mead residue inside. From there the recipe for mead traveled to Europe and Africa or perhaps developed in these places independently. In both locations historians believe mead caught on in places where the climates and or soils didn’t support healthy grape production. With no ability to make wine, mead was a great option, since all one needed was access to bees and water.

Frank Thadeusz wrote in Spiegel Online: “Archaeologists have long pondered the question of which came first, bread or beer. McGovern surmises that these prehistoric humans didn’t initially have the ability to master the very complicated process of brewing beer. However, they were even more incapable of baking bread, for which wild grains are extremely unsuitable. They would have had first to separate the tiny grains from the chaff, with a yield hardly worth the great effort. If anything, the earliest bakers probably made nothing more than a barely palatable type of rough bread, containing the unwanted addition of the grain’s many husks. [Source: Spiegel Online, By Frank Thadeusz, December 24, 2009 /~]

“It’s likely, therefore, that early farmers first enriched their diet with a hybrid swill — half fruit wine and half mead — that was actually quite nutritious. Neolithic drinkers were devoted to this precious liquid. At the excavation site of Hajji Firuz Tepe in the Zagros Mountains of northwestern Iran, McGovern discovered prehistoric wine racks used to store airtight carafes. Inhabitants of the village seasoned their alcohol with resin from Atlantic Pistachio trees. This ingredient was said to have healing properties, for example for infections, and was used as an early antibiotic. /~\

“The village’s Neolithic residents lived comfortably in spacious mud brick huts, and the archaeologist and his team found remnants of wine vessels in the kitchens of nearly all the dwellings. “Drinking wasn’t just a privilege of the wealthy in the village,” McGovern posits, and he adds that women drank their fair share as well.

First Wines

Wine has been around for at least 7,000 years. The first people to drink it, perhaps, left some grapes in a container of some sort and came back a few days later to discover that it had changed into wine.

Egyptian wine Intentional wine-making is believed to have begun in the Neolithic period (from about 9500 to 6000 B.C.) when communities settled in year-round settlements and began intentionally crushing and fermenting grapes and tending a grape crop year round. This is believed to have first occurred in Transcaucasus, eastern Turkey or northwestern Iran. Around the same time the Chinese were making wines with rice and local plant food.

Scholars believe that men may have learned what foods to eat by watching other animals, and through trial and error experimentation. Early man may have discovered early intoxicants and medicines this same way.

Winemaking is believed to have been refined through trial and error. One of the biggest hurdles to overcome was manipulating the yeast that turns grape juice into wine and the bacteria that transforms it into vinegar. Many early wines were mixed with pungent tree resins, presumably to help preserve the wine the absence of corks or stoppers. The resin from the ternith tree, a kind of pistachio, was found in wine dated to 5500 B.C.

There are a number of myths and stories about the first wine. According to the Greeks it was invented by Dionysus and spread eastward to Persia and India. Noah raised grapes after the flood and became so enamored with his product that he became the first town drunk. In a Persian legend, wine was discovered by a concubine of the legendary King Jamsheed, who suffered from splitting headache and accidently drank from jar with spoiled fruit and fell into a deep sleep and awoke cured and feeling refreshed. Afterwards the king ordered his grape stocks to be used to make wine, which was spread around the world.

Book: “Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages” and “Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture” by Patrick E. McGovern (Princeton University Press, 2003). McGovern is an ancient-wine expert and a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.

Oldest Known Wine — From China

Vessels with the

oldest wine

The earliest evidence of wine making has been found in China: traces of a mixed fermented drink made with rice, honey, and either grapes or Hawthorne fruit found on pottery shards dated to 7,000 B.C. found near the village of Jiahu in Henan Province northern China. Wine has also reportedly been found on a pottery sample from a Chinese tomb dated to 5000 B.C.

Analysis by University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology of the pores of 9000-year-old pottery shards jars unearthed in Jiahu turned up traces of beeswax, a biomarker for honey; tartaric acid, a biomaker for grapes, wine and Chinese hawthorne fruit; and other traces that “strongly suggested” rice.

Grapes were not introduced to China from Central Asia until many millennia after 7000 B.C., so it is reasoned the tartaric acid likely comes from hawthorne fruit which is ideal for making wine because it has a high sugar content and can harbor the yeast for fermentation. Wine traces has also been found in a pottery sample from a Chinese tomb dated to 5000 B.C.

This findings raises the question: which came first grape wine or rice wine. Grape pips, an indication of possible wine making operations, have been found in six millennium B.C. sites in the Dagestan mountains in the Caucasus.

See Separate Articles JIAHU (7000-5700 B.C.): CHINA’S EARLIEST CULTURE AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com JIAHU (7000 B.C. to 5700 B.C.): EARLY FLUTES AND WRITING AND THE WORLD’S OLDEST WINE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Georgia clay jar, researchgate

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024