DRINKS IN ANCIENT ROME

Tavern in Pompeii Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “After water and milk, wine was the ordinary drink of the Romans of all classes. It must be distinctly understood, however, that they always mixed it with water and used more water than wine. Pliny the Elder mentions one wine that would stand being mixed with eight times its own bulk of water. To drink wine unmixed was thought typical of barbarism; wine was so drunk only by the dissipated at their wildest revels. Under the Empire the ordinary qualities of wine were cheap enough to be sold at three or four cents a quart; the choicer kinds were very costly, entirely beyond the reach, Horace gives us to understand, of a man in his circumstances. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

More rarely used than wine were other beverages that are mentioned in literature. A favorite drink was mulsum, made of four measures of wine and one of honey. A mixture of water and honey allowed to ferment together was called mulsa. Cider was made by the Romans, and wines from mulberries and dates. They also made various cordials from aromatic plants.” |+|

The Greeks preferred to drink from small, shallow cups rather than large and deep ones. Chilled fruit juices, milk and honey were enjoyed in the time of Alexander the Great (4th century B.C.). Rites of passage included giving three-year-old children their first jug, from which they had their first taste of wine.

Carla Raimer wrote for PBS.org: “Romans were not averse to drinking alcohol, a habit they carried into the public baths. The Roman philosopher Seneca and the Roman scholar Pliny the Elder both opposed drinking at the baths. The poet Martial complains about one sloppy bather who “doesn’t know how to go home from the baths sober.” [Source: Carla Raimer PBS.org]

A couple of graffiti wall Inscriptions from Pompeii read: . 1)“The whole company of late drinkers favor Vatia.” 2) “The whole company of late risers favor Vatia.” Maybe Vatia was a politician running for office. [Source: William Stearns Davis, ed., “Readings in Ancient History: Illustrative Extracts from the Sources,” 2 Vols. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1912-13), Vol. II: Rome and the West, pp. 260-265]

Categories with related articles in this website: Early Ancient Roman History (34 articles) factsanddetails.com; Later Ancient Roman History (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Life (39 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Religion and Myths (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Art and Culture (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Roman Government, Military, Infrastructure and Economics (42 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy and Science (33 articles) factsanddetails.com; Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Forum Romanum forumromanum.org ;

“Outlines of Roman History” forumromanum.org; “The Private Life of the Romans” forumromanum.org|; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu;

Gutenberg.org gutenberg.org

The Roman Empire in the 1st Century pbs.org/empires/romans;

The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ;

Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu;

De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors roman-emperors.org;

British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Oxford Classical Art Research Center: The Beazley Archive beazley.ox.ac.uk ;

Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/about-the-met/curatorial-departments/greek-and-roman-art;

The Internet Classics Archive kchanson.com ;

Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org/web; Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy iep.utm.edu;

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu;

Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ;

History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame /web.archive.org ;

United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

See Separate Article:

ORIGIN OF ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST WINES, WINEMAKING, WINERIES AND WINE GRAPES factsanddetails.com ;

EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com ;

DRINKS IN MESOPOTAMIA: MAINLY BEER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DRINKS: BEER, WINE, MILK AND WATER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WINE, DRINKING AND DRINKS IN ANCIENT GREECE europe.factsanddetails.com ;

Alcoholic Drinks in Ancient Greece

Bowl for mixing wine and water

Romans drank cider as early as 55 B.C. Beer was available but it was regarded as “not for the sophisticated." It was much more popular in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. There was no whiskey or brandy. The distillation of alcohol had not been invented. There was no coffee or tea either.

Wine was far and away the main alcoholic drink. It was consumed with meals and at parties, regarded as sources of good conversation and extolled in poems and songs. Grape juice became wine quickly because there was no refrigeration or preservatives in ancient times.

The Greeks drank a lot wine but associated drunkenness with overindulgence and lack of discipline. According to their custom the Greeks mixed five parts water and two parts wine and sometimes added honey and salt water as flavoring. The Greeks believed that drinking undiluted wine could cause blindness, insanity or other terrible things. Later the Franks popularized the custom of drinking wine straight.

Men used to hang out at wine shops where strong syrupy wine was poured from an amphorae and diluted with water in a large mixing bowl. Rich Greeks and Romans chilled their wine with snow kept in straw lined pits, even though Hippocrates thought that "drinking out of ice" was unhealthy.

The wine from Kos was good and relatively inexpensive. Higher quality wines came from Rhodes. Artemidorus described a drink called melogion which "is more intoxicating than wine" and "made by first boiling some honey with water and then adding a bit of herb." Homer described a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey and goat cheese. Kottoabis is one of the world first known drinking games, A fixture of all-night parties and reportedly even played by Socrates, the game involved flinging the dregs left over from a cup of wine at a target. Usually the participants sat in a circle and tossed their dregs at the basin in the center.

Gladiator Energy Drinks

It appears that energy drinks may have been as common among ancient Roman gladiators and athletes as they are among modern athletes. Said to have performance-enhancing abilities, these drinks often architecture plant ash, a rich source of calcium that is known to help improve bone growth. High calcium levels are common in excavated gladiators. How did it taste? Like ash and water, with vinegar added to make it taste better. [Source: Gordon Gora. Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Tia Ghose wrote in Livescience: “The skeletal remains of gladiators unearthed in a cemetery in Ephesus, Turkey, suggest the fighters may have drunk a beverage made from ash, vinegar and water. The new analysis, which was detailed online in the journal PLOS ONE, also casts doubt on the notion that the fighters ate a special gladiator diet, as historical documents suggest. The gladiators' mostly vegetarian fare wouldn't have been much different from the diet of the general population, said study co-author Fabian Kanz, a forensic anthropologist at the Medical University of Vienna in Austria. [Source: Tia Ghose, Livescience, October 27, 2014]

“The team analyzed the ratio of the elements strontium and calcium in the bones. Strontium is readily taken up from the soil by plants, but is removed from the body by animals that eat those plants or other animals, Kanz told Live Science. However, a strontium atom will occasionally replace a calcium atom in the bones, so planet eaters and those eating lower in the food chain will have higher levels of strontium, Kanz added.

“The team found that the gladiators had almost twice the ratio of strontium to calcium in their bones, as did other populations, even though they ate a very similar diet. That led the researchers to speculate that the gladiators were guzzling a post-battle drink described in ancient texts: a mixture of vinegar, water and ash. The ash, which Romans typically added to food for a smoky flavor and even used for medicinal purposes, would have provided an extra heaping of strontium, Kanz said. "They didn't have coffee; they didn't have tea," Kanz told Live Science. "But they had wine, and then they drank a mixture of vinegar and water. It's not as horrible as it sounds." With some good vinegar, the drink might have tasted like refreshing lemonade, Kanz said.”

Donkey Milk and Goat Dung Energy Drink in Ancient Rome

Mark Oliver wrote for Listverse:“Romans didn’t have Band-Aids, so they found another way to patch up wounds. According to Pliny the Elder, people in Rome patched up their scrapes and wounds with goat dung. Pliny wrote that the best goat dung was collected during the spring and dried but that fresh goat dung would do the trick “in an emergency.” [Source: Mark Oliver, Listverse, August 23, 2016 +++]

the energy of a donkey was greatly admired in Rome

“That’s an attractive image, but it’s hardly the worst way Romans used goat dung. Charioteers drank it for energy. They either boiled goat dung in vinegar or ground it into a power and mixed it into their drinks. They drank it for a little boost when they were exhausted. This wasn’t even a poor man’s solution. According to Pliny, nobody loved to drink goat dung more than Emperor Nero himself.” +++

“Donkey milk was hailed by the ancients as an elixir of long life, a cure-all for a variety of ailments, and a powerful tonic capable of rejuvenating the skin. Cleopatra, Queen of Ancient Egypt, reportedly bathed in donkey milk every day to preserve her beauty and youthful looks, while ancient Greek physician Hippocrates wrote of its incredible medicinal properties....Legend has it that Cleopatra (60 – 39 B.C.), the last active Pharaoh of Egypt, insisted on a daily bath in the milk of a donkey (ass) to preserve the beauty and youth of her skin and that 700 asses were need to provide the quantity needed. It was believed that donkey milk renders the skin more delicate, preserves its whiteness, and erases facial wrinkles. According to ancient historian Pliny the Elder, Poppaea Sabina (30 – 65 AD), the wife of Roman Emperor Nero, was also an advocate of ass milk and would have whole troops of donkeys accompany her on journeys so that she too could bathe in the milk. Napoleon’s sister, Pauline Bonaparte (1780–1825 AD), was also reported to have used ass milk for her skin’s health care. [Source:worldtruth.tv, February 1, 2015]

“Greek physician Hippocrates (460 – 370 B.C.) was the first to write of the medicinal virtues of donkey milk, and prescribed it as a cure a diverse range of ailments, including liver problems, infectious diseases, fevers, nose bleeds, poisoning, joint pains, and wounds. Roman historian Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 AD) also wrote extensively about its health benefits. In his encyclopedic work Naturalis Historia, volume 28, dealing with remedies derived from animals, Pliny added fatigue, eye stains, weakened teeth, face wrinkles, ulcerations, asthma and certain gynecological troubles to the list of afflictions it could treat: “Asses’ milk, in cases where gypsum, white-lead, sulphur, or quick-silver, have been taken internally. This last is good too for constipation attendant upon fever, and is remarkably useful as a gargle for ulcerations of the throat. It is taken, also, internally, by patients suffering from atrophy, for the purpose of recruiting their exhausted strength; as also in cases of fever unattended with head-ache. The ancients held it as one of their grand secrets, to administer to children, before taking food, a semisextarius of asses’ milk.”

Wine in Ancient Rome

wine making

Wine was far and away the main alcoholic drink. It was consumed with meals and at parties, regarded as sources of good conversation and extolled in poems by some of Rome's greatest writers. Ovid wrote: “There, when the wine is set, you will tell me many a tale — how your ship was all but engulfed in the midst of the waters, and how, while hastening home to me, you feared neither hours of unfriendly night nor headlong winds of the south."

Grape juice became wine quickly because there was no refrigeration or preservatives in ancient times. Roman wine tended to be sweet and highly alcoholic because late season grapes were used. Romans followed the Greek custom and diluted their wine with water: the common belief was that only Barbarians would drink it straight. The water content depended on the setting. At family meals water to wine ratio was about 3:1. In taverns there was often little water. The wine was often safer to drink than the water. The acids and the alcoholic curbed the growth of bacteria and other pathogens.

To sweeten their wine, which could be vinegary, Romans added honey and water to it. Better grades went to the elite while cheaper, vinegary stuff went to slaves. Mario Indelicato, an archaeologist at the University of Catania in Sicily told The Guardian: “An edict was issued in the first century A.D. halting the planting of vineyards because people were not growing wheat any more,” said Indelicato. The Romans took the concept of getting together for a drink from the Greeks after they conquered the Greek-controlled Italian city of Taranto in the third century B.C. They drank at festivals to mark the pending harvest, after the harvest. In fact, any occasion was good for a drink.” [Source: Tom Kington, guardian.com, August 22, 2013]

Romans believed that wine was a medicine. Roman soldiers were required to drink a liter of wine a day. Families often had it with every meal. The rich took trouble to drink wine in especially beautiful places like gardens when certain flowers were in bloom. Taverns were filled large jug-like amphoras which were filed with wine.

Book: “VINUM: The Story of Roman Wine” by Stuart Fleming (Glen Mills, PA, Art Flair, 2001)

Wine Drinking in Ancient Rome

From what best can be determined everybody drank: from the rich in lavish villas to soldiers and sailors in provincial inns. For some wine-making was the life’s greatest pleasure. One tombstone in Tibur, just outside Rome, read: “Flavius Agricola [was] my name...Friends who read this listen to my advice: Mix wine, then place the garlands around you head, drink deep. And do not deny pretty girls the sweets of love.”

By some estimates Rome's 1 million citizens and slaves drank an astonishing average of three liters of wine a day. Although most everyone drank wine diluted with water, people complained if they thought they were being shortchanged. One piece of graffiti found read, “May cheating like this trip you up bartender. You sell water and yourself drink undiluted wine.

Katharine Raff of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “At the Roman banquet, wine was served throughout the meal as an accompaniment to the food. This practice contrasted with that of the Greek deipnon, or main meal, which focused on the consumption of food; wine was reserved for the symposium that followed. Like the Greeks, the Romans mixed their wine with water prior to drinking. The mixing of hot water, which was heated using special boilers known as authepsae, seems to have been a specifically Roman custom. Such devices (similar to later samovars) are depicted in Roman paintings and mosaics, and some examples have been found in archaeological contexts in different parts of the Roman empire. Cold water and, more rarely, ice or snow were also used for mixing. Typically, the wine was mixed to the guest's taste and in his own cup, unlike the Greek practice of communal mixing for the entire party in a large krater (mixing bowl). Wine was poured into the drinking cup with a simpulum (ladle), which allowed the server to measure out a specific quantity of wine.” [Source: Katharine Raff, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

There were a number of ideas circulated around of how to improve the taste of wine. Pliny the Elder recommended adding “seawater to enliven the smoothness." Cato liked to drink his wine flavored with a drop of pig's blood and a pinch of marble dust. The archaeologist and winemaker Herve Durad told Bloomberg News, “The soldiers didn't care if it turned to vinegar. It gave them energy." Pliny the Elder also wrote that it was common to find drowned mice in wine-filled storage vessels. When this occurred he suggested removing the marinated mouse and roasting it.

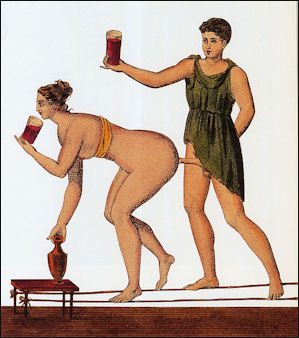

The Romans played drinking games, A depiction of a drinking game in The House of Chaste Lovers in Pompeii shows one person still drinking while another is slumped over a couch, defeated

Estate owners valued their vineyards and inscribed tributes such as “nectar-sweet juices” and “the gift of Bacchus” on their winepresses. Innkeepers inscribed wine lists and prices on the wall of their facilities.

Types of Wine in Ancient Rome

.jpg)

Bar in PompeiiHoneyed wine called mulsum was very popular. This sweet Roman drink — a simple mixture of wine and honey — can ne made today by warm a half cup of clear honey and adding it to a bottle of medium-dry white wine. Chill before serving.

Massilitanum was a heavy wine that Galen regarded as delightful and good for health but Martial thought was so bad it should only be given to homeless people to poison them. At parties the wine was often sprinkled with euphrosynum (“the plant of cheers”) or hiera botane (“the sacred plant”) to keep the conservation going and keep spirits high. In Egypt, people made wine from raisins and dates.

Many of the vineyards in the Moselle Valley in Germany were originally planted by the Romans. Turricuar was a dry white wine the Romans liked to consume with fish and oysters. It was yellowish in color and is spiked with seawater. It tastes slightly of prunes and is made today using a recipe described by Roman agronomist Lucius Columelle.

Falernian wine, grown with Aminean grapes on mountain slopes south of present-day Naples, was particularly prized. To improve its flavor the wine was aged in large clay amphorae for a decade or more until it turned a delicate amber color. A liter cost about $110 in today's money. Premium 160-year-old vintages were reserved for the Emperor and served in crystal goblets. Those that could afford it clearly loved to brag about. One tombstone read: “In the grave I lie. Who was once well known as Primus. I lived on Lucrine oysters, often drank Falernian wines. The pleasures of bathing, wine and love gave me over the years."

The wines from Gaul (France) were said to be “brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy” but left “a nasty hangover.” Even so it seems that the Romans loved it. In 2009, it was announced that a shipwreck dating to the A.D. 2nd century found off Cape Greco, Cyprus contained over 130 ceramic jars, likely to have been carrying wine or oil. The Cyprus Department of Antiquities said “Its location in shallow waters, suggest that either the vessel was nearing an intended port-of-call, or else was engaged in a coasting trade, moving products to market over short distances up and down the coast...While most jars came from South Eastern Asia Minor and the general North East Mediterranean region, one group of amphorae appears to have contained wine imported from the Mediterranean coast of France.” [Source: Patrick Dewhurst, 2009]

In Mas des Tourelles near the Provence town of Beaucair in southern France, a group of archaeologists spent $20,000 to reopen the largest winery in Gaul after 1,800 years. The opened in the early 1990s it sells wine for about $12 a bottle. In Caesar’s time the facility produced the equivalent of 100,000 modern-size bottles of wine a day and each bottle sold for about 1 sesterce (about $1.60). The entire region produced about 27 million liters a year, enough to fill 2 million clay amphorae for shipment by oxen throughout the Mediterranean. [Source: Craig Copetas, Bloomberg News, December 2002]

The Mas des Tourelles wine is brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy but it leaves a nasty hangover. Those who tried it described it as a “curiosity” and said “eat a lot of goat cheese and nuts when you — drink it.

Men used to hang out at wine shops where strong syrupy wine was poured from an amphorae and diluted with water in a large mixing bowl. Rich Greeks and Romans chilled their wine with snow kept in straw lined pits, even though Hippocrates thought that "drinking out of ice" was unhealthy.

The wine from Kos was good and relatively inexpensive. Higher quality wines came from Rhodes. Artemidorus described a drink called “ melogion” which "is more intoxicating than wine" and "made by first boiling some honey with water and then adding a bit of herb." Homer described a drink made from wine, barley meal, honey and goat cheese.

“Kottoabis” is one of the world first known drinking games, A fixture of all-night parties and reportedly even played by Socrates, the game involved flinging the dregs left over from a cup of wine at a target. Usually the participants sat in a circle and tossed their dregs at the basin in the center.

Grapes, Vineyards and Viticulture in the Roman Era

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: “Grapes were eaten fresh from the vines and were also dried in the sun and kept as raisins, but they owed their real importance in Italy as elsewhere to the wine made from them. It is believed that the grapevine was not native to Italy, but was introduced, probably from Greece, in very early times. The first name for Italy known to the Greeks was Oenotria, a name which may mean “the land of the vine”; very ancient legends ascribe to Numa restrictions upon the use of wine. It is probable that up to the time of the Gracchi wine was rare and expensive. The quantity produced gradually increased as the cultivation of cereals declined, but the quality long remained inferior; all the choice wines were imported from Greece and the East. By Cicero’s time, however, attention was being given to viticulture and to the scientific making of wines, and by the time of Augustus vintages were produced that vied with the best brought from abroad. Pliny the Elder says that of the eighty really choice wines then known to the Romans two-thirds were produced in Italy; and Arrian, about the same time, says that Italian wines were famous as far away as India. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Grapes could be grown almost anywhere in Italy, but the best wines were made south of Rome within the confines of Latium and Campania. The cities of Praeneste, Velitrae, and Formiae were famous for the wine grown on the sunny slopes of the Alban hills. A little farther south, near Terracina, was the ager Caecubus, where was produced the Caecuban wine, pronounced by Augustus the noblest of all. Then came Mt. Massicus with the ager Falernus on its southern side, producing the Falernian wines, even more famous than the Caecuban. Upon and around Vesuvius, too, fine wines were grown, especially near Naples, Pompeii, Cumae, and Surrentum. Good wines, but less noted than these, were produced in the extreme south, near Beneventum, Aulon, and Tarentum. Of like quality were those grown east and north of Rome, near Spoletium, Caesena, Ravenna, Hadria, and Ancona. Those of the north and west, in Etruria and Gaul, were not so good. |+|

“The sunny side of a hill was the best place for a vineyard. The vines were supported by poles or trellises in the modern fashion, or were planted at the foot of trees up which they were allowed to climb. For this purpose the elm (ulmus) was preferred, because it flourished everywhere, could be closely trimmed without endangering its life, and had leaves that made good food for cattle when they were plucked off to admit the sunshine to the vines. Vergil speaks of “marrying the vine to the elm,” and Horace calls the plane tree a bachelor (platanus caelebs), because its dense foliage made it unfit for the vineyard. Before the gathering of the grapes the chief work lay in keeping the ground clear; it was spaded over once each month in the year. One man could properly care for about four acres.” |+|

In 2012, Nancy Thomson de Grummond of Florida State University announced that she had discovered some 150 waterlogged grape seeds in a well in Cetamura del Chianti Italy and probably date to about the A.D. 1st century. There is possibility the seeds’ DNA can analyzed. The seeds could provide “a real breakthrough” in the understanding of the history of Chianti vineyards in the area, de Grummond said. “We don’t know a lot about what grapes were grown at that time in the Chianti region.“Studying the grape seeds is important to understanding the evolution of the landscape in Chianti. There’s been lots of research in other vineyards but nothing in Chianti.” [Source: Elizabeth Bettendorf, Phys.org, December 6, 2012]

Ancient Roman Wine Making

Ancient Roman winemakers used tasting spoons and grape presses, some of which are now displayed in museums. Wine was often stored in 26-liter amphorae which had vineyard name and year labeled on them. Estate owners valued their vineyards and inscribed tributes such as “nectar-sweet juices” and “the gift of Bacchus” on their winepresses.

The grapes were usually crushed by foot by slaves, then the mixture was crushed further by a winepress and a stone weight lowered by a tree trunk. The juices flowed down a stem to a waiting pool where it was scooped out and placed in 400-liter clay pots packed with honey, thyme, pepper and other spices. Workers mixed the brew with broomsticks wrapped in fennel. After six days to three weeks in a clay fermentation tub the mixture turned into a foamy red liquid with about 12 percent alcohol. The wine was drinkable for about 10 days before it went bad.

Harold Whetstone Johnston wrote in “The Private Life of the Romans”: The making of the wine took place usually in September; the season varied with the soil and the climate. It was anticipated by a festival, the vinalia rustica, celebrated on the nineteenth of August. Precisely what the festival meant the Romans themselves did not fully understand, perhaps, but it was probably intended to secure a favorable season for the gathering of the grapes. The general process of making the wine differed little from that familiar to us in Bible stories and still practiced in modern times. After the grapes were gathered, they were first trodden with the bare feet and then pressed in the prelum or torcular. The juice as it came from the press was called mustum (vinum), “new (wine),” and was often drunk unfermented, as sweet cider is now. It could be kept sweet from vintage to vintage by being sealed in a jar smeared within and without with pitch and immersed for several weeks in cold water or buried in moist sand. It was also preserved by evaporation over a fire; when it was reduced one-half in this way, it became a grape jelly (defrutum) and was used as a basis for various beverages and for other purposes. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) forumromanum.org |+|]

“Fermented wine (vinum) was made by collecting the mustum in huge vat-like jars (dolia). One of these was large enough to hide a man and held a hundred gallons or more. These were covered with pitch within and without and partially buried in the ground in cellars or vaults (vinariae cellae), in which they remained permanently. After they were nearly filled with the mustum, they were left uncovered during the process of fermentation, which lasted under ordinary circumstances about nine days. They were often tightly sealed, and opened only when the wine required attention3 or was to be removed. The cheaper wines were used directly from the dolia; but the choicer kinds were drawn off after a year into smaller jars (amphorae), clarified and even “doctored” in various ways, and finally stored in depositories often entirely distinct from the cellars. A favorite place was a room in the upper story of the house, where the wine was aged by the heat rising from a furnace or even by the smoke from the hearth. The amphorae were often marked with the name of the wine, and the names of the consuls for the year in which they were filled.” |+|

grape crushing

First Wines

Intentional wine-making is believed to have begun in the Neolithic period (from about 9500 to 6000 B.C.) when communities settled in year-round settlements and began intentionally crushing and fermenting grapes and tending a grape crop year round. This is believed to have first occurred in Transcaucasus, eastern Turkey or northwestern Iran. Around the same time the Chinese were making wines with rice and local plant food.

Scholars believe that men may have learned what foods to eat by watching other animals, and through trial and error experimentation. Early man may have discovered early intoxicants and medicines this same way.

Winemaking is believed to have been refined through trial and error. One of the biggest hurdles to overcome was manipulating the yeast that turns grape juice into wine and the bacteria that transforms it into vinegar. Many early wines were mixed with pungent tree resins, presumably to help preserve the wine the absence of corks or stoppers. The resin from the ternith tree, a kind of pistachio, was found in wine dated to 5500 B.C.

There are a number of myths and stories about the first wine. According to the Greeks it was invented by Dionysus and spread eastward to Persia and India. Noah raised grapes after the flood and became so enamored with his product that he became the first town drunk. In a Persian legend, wine was discovered by a concubine of the legendary King Jamsheed, who suffered from splitting headache and accidently drank from jar with spoiled fruit and fell into a deep sleep and awoke cured and feeling refreshed. Afterwards the king ordered his grape stocks to be used to make wine, which was spread around the world.

See Separate Articles FIRST WINES, WINERIES AND ALCOHOLIC DRINKS factsanddetails.com ; EARLIEST BEER factsanddetails.com

Archaeologists Make Wine As the Romans Did

In the 1990s, group of archaeologists spent $20,000 to reopen the largest winery in Gaul — in Mas des Tourelles near the Provence town of Beaucair in southern France — a after 1,800 years, selling the wine for about $12 a bottle. In Caesar's time the facility produced the equivalent of 100,000 modern-size bottles of wine a day and each bottle sold for about 1 sesterce (about $1.60). The entire region produced about 27 million liters a year, enough to fill 2 million clay amphorae for shipment by oxen throughout the Mediterranean. The Mas des Tourelles wine is brownish red and sweet with a taste of preach and caramel candy but it leaves a nasty hangover. Those who tried it described it as a “curiosity” and said “eat a lot of goat cheese and nuts when you drink it.”“ [Source: Craig Copetas, Bloomberg News, December 2002]

Tom Kington wrote in The Guardian: “Archeologists in Italy have set about making red wine exactly as the ancient Romans did, to see what it tastes like. Based at the University of Catania in Sicily and supported by Italy’s national research centre, a team has planted a vineyard near Catania using techniques copied from ancient texts and expects its first vintage within four years. “We are more used to archeological digs but wanted to make society more aware of our work, otherwise we risk being seen as extraterrestrials,” said archaeologist Daniele Malfitana. [Source: Tom Kington, guardian.com, August 22, 2013]

“At the group’s vineyard, which should produce 70 litres at the first harvest, modern chemicals will be banned and vines will be planted using wooden Roman tools and will be fastened with canes and broom, as the Romans did. Instead of fermenting in barrels, the wine will be placed in large terracotta pots – traditionally big enough to hold a man – which are buried to the neck in the ground, lined inside with beeswax to make them impermeable and left open during fermentation before being sealed shut with clay or resin. “We will not use fermenting agents, but rely on the fermentation of the grapes themselves, which will make it as hit and miss as it was then – you can call this experimental archaeology,” said researcher Mario Indelicato, who is managing the programme.

“The team has faithfully followed tips on wine growing given by Virgil in the Georgics, his poem about agriculture, as well as by Columella, a first century A.D. grower, whose detailed guide to winemaking was relied on until the 17th century. “We have found that Roman techniques were more or less in use in Sicily up until a few decades ago, showing how advanced the Romans were,” said Indelicato. “I discovered a two-pointed hoe at my family house on Mount Etna recently that was identical to one we found during a Roman excavation.” What has changed are the types of grape varieties, which have intermingled over the centuries. “Columella mentions 50 types but we can only speculate on the modern-day equivalents,” said Indelicato, who is planting a local variety, Nerello Mascalese.

19th century vision of a Greek wine festival

Pompeii Wine Brought Back to Life

In 2016, The Local reported: “Made from ancient grape varieties grown in Pompeii, ‘Villa dei Misteri’ has to be one of the world’s most exclusive wines. The grapes are planted in exactly the same position, grown using identical techniques and grow from the same soil the city’s wine-makers exploited until Vesuvius buried the city and its inhabitants in A.D. 79. [Source: the local.it, February 2016]

“In the late 1800s, archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli first excavated some of the city’s vineyards from beneath three metres of solid ash. The digs turned up an almost perfect snapshot of ancient wine-growing – and thirteen petrified corpses, huddled against a wall. Casts were made of the bodies, as well as the vines and the surviving segments of trellises on which they were growing. But archaeologists didn’t think to restore the vineyards of ancient Pompeii until the late 1980s.

“When they did, they realized they didn’t have a clue about wine-making, so they called in local winemaker Piero Mastrobeardino. Together they set out to discover how the ancient Romans made wine, and which grapes and farming methods they used. “The team looked at casts of vine roots made two centuries ago and consulted the surviving fragments of ancient farming texts,” Mastrobeardino told The Local. “We even looked at ancient frescoes to try to identify which grapes grew from Pompeii’s soil.” The team discovered that the type of grapes their ancestors were growing, called Piederosso Sciacinoso and Aglianico, were the same varieties still being grown on the slopes of Vesuvius by local farmers. Aglianico is a variety which Piero’s father is credited for saving from extinction after the Second World War.

“Although the grape varieties were still the same, farming techniques had changed significantly since the time of the Romans. “We use a number of methods to grow the fruit and carry out all of the work manually. One thing all our farming techniques have in common is that the grapes are grown at an extremely high density,” Mastrobeardino explained. At first, experts doubted whether the grapes would grow at all at yields almost twice as high as those used today. However, once placed back in Pompeii’s fertile soil, they flourished. Enologists discovered that the Romans’ high-density growth technique is actually beneficial – the technique, now rediscovered, is spreading to the modern wine-making.

“But not everything about ancient wine-making was better. Mastrobeardino ferments the wine according to modern techniques and says Roman wine tasted foul. Pompeii wines were fermented in open-topped terracotta pots, called dolia. These were lined with pine resin filled with wine and buried deep into the earth. Asking a modern wine-lover to drink ancient wine would be foolish. The Romans knew their system was far from perfect but didn’t have the technology to change it.”

“Pompeii wines were considered among the best in the Empire, but were fiercely alcoholic and often diluted with honey, spices and even seawater to mask their rancid flavour. Some 1,500 bottles of Villa dei Misteri are made each year and can be found on the tables of exclusive restaurants in Tokyo, London and New York, Mastrobeardino said. “It’s more of a research project than a commercial enterprise, but it has come a long way. We have now replanted 15 of the city’s ancient vineyards and are experimenting with diverse ancient farming techniques and grape blends.” It might not be a profitable enterprise, but it doesn’t come cheap either – a bottle will set you back around €77.”

Hellenistic drinking scene in Gandhara, Pakistan

Industrial-Scale, Emperor-Owned, Imperial Roman State Vineyard

In 2016, researchers from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Archaeology investigating the vast Imperial estate of Vagnari in Italy, announced they had discovered evidence of wine production on an industrial scale carried about some of Rome’s greatest leaders. According to the University of Sheffield: “The excavation team discovered the corner of a cella vinaria, a wine fermentation and storage room, in which wine vessels, known as dolia defossa, were fixed into the ground. The heavy and cumbersome wine vessels have the capacity of more than 1,000 litres and were buried up to their necks in the ground to keep the temperature of the wine constant and cool – a necessary measure in hot climates. [Source: University of Sheffield, April 11, 2016]

“The scale of the wine production provides clear evidence for industrial activities and provides a glimpse into the range of specialist crafts and industries practised by residents - painting a better and more complete picture of life on the Imperial estate and the wealth it provided for its owner. Maureen Carroll, Professor of Roman Archaeology at the University of Sheffield, said: “Before we began our work only a small part of the vicus, which is at the heart of the estate and its administrative core, had been explored though the general size and outline of the village had been indicated by geophysics and test-trenching. “The discovery that lead was being processed here at Vagnari is also particularly revealing about the environment in which the inhabitants of the village lived and potential health risks to which they were exposed.

“Vagnari is situated in a valley of the Basentello river, just east of the Apennine mountains in Puglia (ancient Apulia) in south-east Italy. After the Roman conquest of the region in the 3rd century B.C., Vagnari was linked to Rome by one of Italy’s main Roman roads, the Via Appia. Excavation and survey by British, Canadian and Italian universities since 2000 have furnished evidence for a large territory that was acquired by the Roman emperor and transformed into imperial landholdings at some point in the early 1st century A.D. Professor Carroll added: “Few Imperial estates in Italy have been investigated archeologically, so it is particularly gratifying that our investigations at Vagnari will make a significant contribution to the understanding of Roman elite involvement in the exploitation of the environment and control over free and slave labour from the early 1st century AD.”

Carroll wrote: “Each basin held a pitch-lined ceramic container (dolium defossum) with a rim diameter of over half a metre and a body diameter larger than a metre. Dolia were heavy and cumbersome, with a capacity of 1000 litres and more. They were buried up to their necks in the ground to keep the temperature of the wine constant and cool, a necessary measure in hot climate zones, as Pliny the Elder said (Natural History 14.27). Dolia could be used for many years, although they needed to be cleaned regularly, and even fumigated, to avoid contamination of the new wine with which they were filled. The Roman agrarian writer Columella (On Agriculture 12.18.5-7) recommended that dolia should be re-lined with pitch forty days prior to the grape harvest, and the tenth-century Geoponica (6.4), which drew on earlier Roman books on agricultural pursuits, advised the renewal of the pitch lining every year in July. [Source: Pasthorizonspr.com, Ancientfoods, January 25, 2016 ||||]

“Such wine ‘cellars’, with anywhere between a dozen and forty or more dolia, are known on private farms elsewhere in Roman Italy and the Mediterranean, but at Vagnari the wine came from vineyards belonging to the empire’s greatest landowner. It is currently unknown how extensive the emperor’s vineyards were, and whether they were in the immediate vicinity of the vicus or on outlying tenant farms. Viticulture required not only considerable capital; it was also labour intensive, especially if it involved preparing new ground for vines, and it took several years before the first harvest could take place. According to Columella (On Agriculture 3.3.8), the standard size for a vineyard was 7 jugera (1.75 hectares), which is what a single slave vine-dresser could cope with. Cato (On Agriculture 11.1) recommended a slave staff of 16 for a vineyard of 100 jugera (25.2 hectares). We do not know how many labourers and specialists were involved in the tending of vineyards and the making of wine at Vagnari, but a workforce of adequate size, along with additional staff recruited A.D. hoc for the peak season of the harvest, certainly will have been maintained. We have yet to determine whether the wine at Vagnari was for the emperor’s consumption, or for sale or export to raise money for the imperial coffers, but the latter is more likely, given that a profitable return will have been expected on an estate whose primary function was to generate income for the emperor. ||||

“We have only explored a corner of the cella vinaria, and revealed three dolia thus far, and there is clearly more of the wine ‘cellar’ to uncover. We expect to find more dolia, probably arranged in regular rows, as in other wine storage areas of Roman date. Excavations in 2016 will clarify the extent of the storage room, the total number of dolia of the emperor’s wine, and the volumetric storage capacity of the structure. We also expect to find other facilities in the complex, such as a wine press and a tank for the pressed grape juice or must. In addition to the costs involved in the preparation of the land, the vines and their maintenance, and the relevant personnel, the buildings, the dolia, and the necessary presses also will have represented a considerable outlay of capital. ||||

“It remains to be determined how the rooms adjacent to the cella vinaria were used. Excavated fragments of white and grey marble slabs with traces of mortar on the underside suggests that this stone had been used for cladding of some kind, perhaps as a dado at the base of walls, and a concentration of glass panes at the foot of a wall implies that there were paned windows in the building. Both the marble cladding and the glass windows demonstrate that these rooms were well appointed, possibly because they were used also for domestic occupation, as a large deposit of household waste, including pottery, bone implements, and animal bones as the remains of meals, in a room east of the winery suggests.”

Bar in Pompeii

Roman-Era Tavern Found in France

In 2016, a Roman-ere tavern, still littered with animal bones and the bowls used by patrons, was discovered in Lattara, an important historical site in France,. The tavern was most likely used during 175–75 B.C., around the time the Roman army conquered the area. The tavern served drinks as well as flatbreads, fish, and choice cuts of meat from sheep and cows. In the kitchen, there were three large ovens on one end and millstones for making flour on the other. In the serving area was a large fireplace and reclining seats.

Laura Geggel wrote in LiveScience: “An excavation uncovered dozens of other artifacts, including plates and bowls, three ovens, and the base of a millstone that was likely used for grinding flour, the researchers said. The finding is a valuable one, said study co-researcher Benjamin Luley, a visiting assistant professor of anthropology and classics at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. Before the Romans invaded the south of France, in 125 B.C., a culture speaking the Celtic language lived there and practiced its own customs. The new findings suggest that some people under the Romans stopped preparing their own meals and began eating at communal places, such as taverns. “Rome had a big impact on southern France,” Luley told Live Science. “We don’t see taverns before the Romans arrive.”[Source: Laura Geggel, LiveScience, March 10, 2016]

“The excavated area includes a courtyard and two large rooms; one was dedicated to cooking and making flour, and the other was likely reserved for serving patrons, the researchers said. There are three large bread ovens on one end of the kitchen, which indicates that “this isn’t just for one family,” but likely an establishment for serving many people, Luley said. On the other side of the kitchen, the researchers found a row of three stone piles, likely bases for a millstone that helped people grind flour, Luley said. “One side, they’re making flour. On the other side, they’re making flatbread,” Luley said. “And they’re also probably using the ovens for other things as well.” For example, the archaeologists found lots of fish bones and scales that someone had cut off during food preparation, Luley added.

“The other room was likely a dining room, the researchers said. The archaeologists uncovered a large fireplace and a bench along three of the walls that would have accommodated Romans, who reclined when they ate, Luley said. Moreover, the researchers found different kinds of animal bones, such as wishbones and fish vertebra, which people simply threw on the floor. (At that time, people didn’t have the same level of cleanliness as some do now, Luley noted.)

“The dining room also had “an overrepresentation of drinking bowls,” used for serving wine — more than would typically be seen in a regular house, he said. Next to the two rooms was a courtyard filled with more animal bones and an offering: a buried stone millstone, a drinking bowl and a plate that likely held cuts of meat. “Based upon the evidence presented here, it appears that the courtyard complex … functioned as a space for feeding large numbers of people, well beyond the needs of a single domestic unit or nuclear family,” the researchers wrote in the study. “This is unusual, as large, ‘public’ communal spaces for preparing large amounts of food and eating together are essentially nonexistent in Iron Age Mediterranean France.” Perhaps some of the people of Lattara needed places like the tavern to provide meals for them after the Romans arrived, Luley said. “If they might be, say, working in the fields, they might not be growing their own food themselves,” he said. And though the researchers haven’t found any coins at the tavern yet, “We think that this is a beginning of the monetary economy” at Lattera, Luley said. “The study was published in the journal Antiquity.

Romans and Caledonians Drank Together as a Pub in Northern Britain

In 2012, archaeologists surveying the world’s most northerly Roman fort announced they had found an ancient pub there. George Mair wrote in The Scotsman: “The discovery, outside the walls of the fort at Stracathro, near Brechin, Angus, could challenge the long-held assumption that Caledonian tribes would never have rubbed shoulders with the Roman invaders. Indeed, it lends support to the existence of a more complicated and convivial relationship than previously envisaged, akin to that enjoyed with his patrician masters by the wine-swilling slave Lurcio, played by comedy legend Frankie Howerd, in the classic late 1970s television show Up Pompeii!. [Source: George Mair, scotsman.com, September 8, 2012]

“Stracathro Fort was at the end of the Gask Ridge, a line of forts and watchtowers stretching from Doune, near Stirling. The system is thought to be the earliest Roman land frontier, built around AD70 – 50 years before Hadrian’s Wall. The fort was discovered from aerial photographs taken in 1957, which showed evidence of defensive towers and protective ditches. A bronze coin and a shard of pottery were found, but until now little more has been known about the site. The archaeologists discovered the settlement and pub using a combination of magnetometry and geophysics without disturbing the site and determined the perimeter of the fort, which faced north-south. “Now archaeologists working on “The Roman Gask Project” have found a settlement outside the fort – including the pub or wine bar. The Roman hostelry had a large square room – the equivalent of a public bar – and fronted on to a paved area, akin to a modern beer garden. The archaeologists also found the spout of a wine jug. Dr Birgitta Hoffmann, co-director of the project, said: “Roman forts south of the Border have civilian settlements that provided everything they needed, from male and female companionship to shops, pubs and bath houses.

““It was a very handy service, but it was always taught that you didn’t have to look for settlements at forts in Scotland because it was too dangerous – civilians didn’t want to live too close.“But we found a structure we think could be identifiable as the Roman equivalent of a pub. It has a large square room which seems to be fronting on to an unpaved path, with a rectangular area of paving nearby. We found a piece of highquality, black, shiny pottery imported from the Rhineland, which was once the pouring part of a wine jug. It means someone there had a lot of money. They probably came from the Rhineland or somewhere around Gaul.” We hadn’t expected to find a pub. It shows the Romans and the local population got on better than we thought. People would have known that if you stole Roman cattle, the punishment would be severe, but if they stuck to their rules then people could become rich working with the Romans.”

Opium and Other Drugs in Ancient Greece and Rome

Ancient Greek Olympic athletes took psychedelic mushrooms for a competitive edge. Cannabis was mentioned by the Greco-Roman era physician Galen. Archaeologists in Israel unearthed remains of a teenage girl with the remains of a fetus in her abdomens dated to the 315 A.D. With the remains was ash containing THC (an active ingredient in cannabis). The archaeologists speculate that maybe cannabis was given to the girl as pain relief.

opium poppies

The Greek scholar Theophrastus (371-287 B.C.) wrote about the use of opium poppy juice and mentioned opium in connection with myths of Ceres and Demeter. The founding fathers of medicine, Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides, also wrote about opium. Poppies were also pictured on Greek coins, pottery and jewelry, and on Roman statues and tombs (where poppies symbolized a release from a lifetime of pain).

Ceramic jugs, dated to 1,500 B.C., shaped like an opium capsules and containing stylized incisions were unearthed in Cyprus and believed to have held opium dissolved in wine that was traded with Egypt. Ivory pipes, over 3,200 years old and thought to have been used for smoking opium, were found in a Cyprus temple.

In Greco-Roman times, opium was used in religious rituals, as an ingredient in magic potions and as a painkiller, sedative and sleeping medicine. The potion "to quiet all pain and strife and bring forgetfulness to every ill" taken by Helen of Troy in Homer's Odyssey is believed to have contained opium. Some scholars have suggested that the "vinegar mingled with gall" offered to Christ on the cross contained opium because the Hebrew word for gall ( rôsh ) means opium. Poppies were pictured on Greek coins, pottery and jewelry, and on Roman statues and tombs (where poppies symbolized a release from a lifetime of pain). The Greek scholar Theophrastus (371-287 B.C.) wrote about the use of opium poppy juice and mentioned opium in connection with myths of Ceres and Demeter. Alexander the Great introduced the drug to India and Persia.

At the time of Christ opium was widely used. There are numerous accounts of opium cultivation, opium use in medicine and even opium addiction. The founding fathers of medicine, Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides, all wrote about opium.Marcus Aurelius took opium to sleep and deal with the stress of prolonged military campaigns. The Romans reportedly used toxic does of opium to poison their enemies.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Most of the information about Greco-Roman science, geography, medicine, time, sculpture and drama was taken from "The Discoverers" [∞] and "The Creators" [μ]" by Daniel Boorstin. Most of the information about Greek everyday life was taken from a book entitled "Greek and Roman Life" by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||].

Last updated January 2018