PEILIGANG CULTURE

bone flute

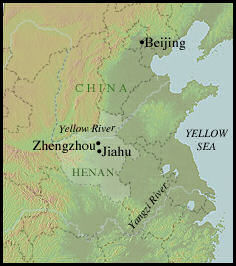

The Peiligang culture is the name given by archaeologists to a group of Neolithic communities in the Yi-Luo river basin in Henan Province, China. The culture existed from 7000 to 5000 B.C.. Over 100 sites have been identified with the Peiligang culture, nearly all of them in a fairly compact area of about 100 square kilometers in the area just south of the river and along its banks. The culture is named after the site discovered in 1977 at Peiligang, a village in Xinzheng County. Archaeologists think that the Peiligang culture was egalitarian, with little political organization. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The site at Jiahu (See Below) is the earliest site associated with Peiligang culture. There are many similarities between the main group of Peiligang settlements and the Jiahu culture, which was isolated several days' travel to the south of the main group. Archaeologists are divided about the relationship between Jiahu and the main group. Most agree that Jiahu was part of the Peiligang culture, pointing to the many similarities. A few archaeologists are pointing to the differences, as well as the distance, believing that Jiahu was a neighbor that shared many cultural characteristics with Peiligang, but was a separate culture. The cultivation of rice, for example, was unique to Jiahu and was not practiced among the villages of the main Peiligang group in the north. Also, Jiahu existed for several hundred years before any of the settlements of the main group. +

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ In the seventh millennium B.C., a widespread culture flourished in pockets throughout the Yellow River Valley. The people in these scattered villages practiced agriculture and animal husbandry, and may have been ancestral to two important later cultures, known as the Yangshao and Longshan cultures. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: ““Most researchers who study the Peiligang culture believe that Peiligang and Jiahu both should be classified as Peiligang culture sites on the basis of some common elements of pottery vessels and stone tools. The Jiahu site should be considered as a variation of the Peiligang culture. There are not as many cultural similarities, however, between Peiligang and Jiahu remains as there are between Peiligang and Cishan remains, especially considering their economies, burial traditions, and the material traces of spiritual life. In fact the differences between Peiligang and Jiahu cultural remains are even greater in these respects. The common elements of Peiligang and Jiahu would have resulted from the coexistence of two cultures adjacent to each other. They should be considered two related cultures that developed at the same time. A comparative analysis of the remains from these two archaeological cultures indicates that the term “Jiahu culture” is appropriate. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; FIRST CROPS AND EARLY AGRICULTURE AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WORLD'S OLDEST RICE AND EARLY RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT FOOD, DRINK AND CANNABIS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINA: THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WRITING? factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC CHINA factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000 B.C. to 5700 B.C.): HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WINE AND SOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST FLUTES, WRITING, POTTERY AND ANIMAL SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; YANGSHAO CULTURE (5000 B.C. to 3000 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; HONGSHAN CULTURE AND OTHER NEOLITHIC CULTURES IN NORTHEAST CHINA factsanddetails.com; LONGSHAN AND DAWENKOU: THE MAIN NEOLTHIC CULTURES OF EASTERN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; KUAHUQIAO AND SHANGSHAN: THE OLDEST LOWER YANGTZE CULTURES AND THE SOURCE OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DOMESTICATED RICE factsanddetails.com; HEMUDU, LIANGZHU AND MAJIABANG: CHINA’S LOWER YANGTZE NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com; EARLY CHINESE JADE CIVILIZATIONS factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC TIBET, YUNNAN AND MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States” (New Studies in Archaeology) by Li Liu Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “New Perspectives on China’s Past: Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century,” edited by Xiaoneng Yang Amazon.com; “The Origins of Chinese Civilization" edited by David N. Keightley Amazon.com; “Liangzhu Culture” by Bin Liu, Ling Qin, et al. Amazon.com; “Hongshan Jade: The oldest, most imaginative jades full of mysterious beauty” Kako Crisci Amazon.com ; “Qijia (Jades of the Qijia and related northwestern cultures of early China, ca. 2100-1600 BCE” by Dr. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson and Gu Fang Amazon.com ; “The Story of Rice” by Xiaorong Zhang Amazon.com

Jiahu

Jiahu is a rich but little known archeological site located near the village of Jiahu near the Yellow River in Henan Province in central China. About equidistant between Xian and Nanjing, the site was occupied from 9,000 to 7,700 years ago and then from 2,000 year ago to the present. In addition to yielding the world’s oldest wine and some of the oldest rice and earliest playable musical instruments, it may have also yielded the earliest examples of Chinese writing.

Laura Anne Tedesco of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The archaeological site of Jiahu in the Yellow River basin of Henan Province, central China, is remarkable for the cultural and artistic remains uncovered there. These remains, such as houses, kilns, pottery, turquoise carvings, tools made from stone and bone—and most remarkably—bone flutes, are evidence of a flourishing and complex society as early as the Neolithic period, when Jiahu was first occupied. [Source: Tedesco, Laura Anne."Jiahu (ca. 7000–5700 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Fragments of thirty flutes were discovered in the burials at Jiahu and six of these represent the earliest examples of playable musical instruments ever found. The flutes were carved from the wing bone of the red-crowned crane, with five to eight holes capable of producing varied sounds in a nearly accurate octave. The intended use of the flutes for the Neolithic musician is unknown, but it is speculated that they functioned in rituals and special ceremonies. Chinese myths known from nearly 6,000 years after the flutes were made tell of the cosmological importance of music and the association of flute playing and cranes. The sound of the flutes is alleged to lure cranes to a waiting hunter. Whether the same association between flutes and cranes existed for the Neolithic inhabitants at Jiahu is not known, but the remains there may provide clues to the underpinnings of later cultural traditions in central China. \^/

“Pictograms, signs carved on tortoiseshells, were also uncovered at Jiahu. In later Chinese culture dating to around 3500 B.C., shells were used as a form of divination. They were subjected to intense heat and the cracks that formed were read as omens. The cracks were then carved as permanent marks on the surface of the shell. The evidence of shell pictograms from Jiahu may indicate that this tradition, or a related one, has much deeper roots than previously considered." \^/

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, two Chinese archeologists involved in the excavations at Jiahu, wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “Due to its early date and rich findings, the Jiahu site provides important information about the development of many aspects of Chinese culture. Since the findings from Jiahu were published, the academic community has been very interested in the bone flutes, objects with inscribed symbols, and the fermented rice beverage documented there. These important discoveries prove that the Jiahu culture played an important role in the development of Chinese civilization.” [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

Peiligang Culture Life

millet

The culture practiced agriculture in the form of cultivating millet and animal husbandry in the form of raising pigs, cattle and poultry. The people hunted deer and wild boar, and fished for carp in the nearby river, using nets made from hemp fibers. The culture is also one of the oldest in ancient China to make pottery. This culture typically had separate residential and burial areas, or cemeteries, like most Neolithic cultures. Common artifacts include stone arrowheads, spearheads and axe heads; stone tools such as chisels, awls and sickles for harvesting grain; and a broad assortment of pottery items for such purposes as cooking and storing grain. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The villages of the Peiligang people included both round and square dwellings, approximately six to ten feet across (a modest room), with plastered floors, sunken beneath ground level. The walls were probably composed of mud and straw, and the roofs were thatched straw. Archaeologists pay great attention to certain aspects of culture that do not necessarily capture our attention in ordinary life: tools, pottery, and burial patterns. These facts can be read from preserved remains; costume, ritual, war, and personality generally cannot. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“We know quite a bit about what these people ate: when the ancient layer of soil that had formed the ground of their villages was excavated, within and around each foundation site were found pits for storage or areas where animals had been kept. The Peiligang people ate several varieties of millet, cabbages, nuts, and fruits. They raised pigs, dogs, and chicken for food, and hunted deer. In other words, their basic patterns of agriculture and husbandry were not radically different from those of much later generations of ancient Chinese. /+/

“Peiligang culture made its implements from three types of materials: stone, bone, and shell. Spears, arrows, and harpoons might all be tools of war, but equally point towards hunting, as do needles that were most likely used to knit nets. Pottery was simple. It was made without a potter’s wheel, decorated with patterns made by pressing cords and combs into the clay, and fired at about 900 degrees Centigrade. /+/

“The dead were buried individually and stretched out. In many cases a few pots or tools were included in the graves; apparently the dead were in need of such objects. But there are not marked distinctions among the graves. This does not appear to have been a culture producing significant surplus for accumulation by individual families or investment in lavish grave rites. Unlike Shang culture, it does NOT bear signs of social stratification. /+/

Jiahu Site

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “The Jiahu site is an early Neolithic site in the Huai river basin. It is located in Jiahu village in Wuyang county, Henan, at latitude N 33̊36 ', longitude E 113̊40 ', 67 meters above sea level. The site lies on the southwestern edge of the vast Huang–Huai–Hai plain. The southern part of the site is close to the Funiu mountains, and rivers are nearby. The site is relatively large in scale (5.5 hectares), well preserved, and has extremely thick cultural deposits. It has a long developmental sequence and large numbers of artifacts. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

“From 1983 to 2001, the Henan Archaeology Institute, University of Science and Technology of China, and other institutes excavated the site seven times. The total excavation area was 2700 square meters. We discovered more than 50 house foundations, 400 storage pits (jiaoxue), more than 10 pottery kilns, around 500 burials, ditches interpreted as moats, other pits, outdoor hearths (zao), and urn burials. We also found thousands of pottery, stone and bone artifacts including tools, utilities, ornaments, and religious objects. Large numbers of plant seeds and animal bones were also present. There was abundant evidence for domesticated rice from fl otation samples, and evidence for early pig domestication (Yuan 2001). Clearly the area was full of faunal and fl oral resources during the time of occupation and was a good place for humans to live. ~|~

There are more than 10 other sites with culturally similar artifacts to Jiahu, such as Guozhung, Dizhung, and Shuiquan. They are mostly located in the Sha and Hung river basin in the upper Huai river area. Now these sites are referred to as Jiahu culture sites (Henan 1999 ; Zhongguo et al. 2002). ~|~

“As discussed below, the discovery of the Jiahu archaeological site provides extremely abundant information for understanding the lives of ancient people in the Huai river Due to its signi ficant cultural value, the National Bureau of Cultural Relics assigned national protection to the Jiahu archaeological site in 2001. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences regards it as one of the 100 most important archaeological discoveries during the 20th century. Jiahu is signi ficant for researching the origin of Chinese Neolithic cultures and the relationship between the Neolithic cultures in the Yellow river and Yangzi river basins (Yu 1999). ~|~

“The cultural deposits at Jiahu were from about 1.5 meters to 2.5 meters thick and were in a succession of three layers, providing reliable data for seriation of the abundant ceramic remains and identi fication of cultural stages (Henan 1999). Ceramic vessel forms such as jars, tripods, basins, and bowls constituted the most abundant pottery types discovered at the site and were key to establishing the cultural phases of the settlement. The stratigraphic superposition of remains at the Jiahu site is very complicated. On the basis of the ceramic seriation and stratigraphic data we identi fied three main phases of development for the site (Henan 1999). In order to obtain absolute dates, we employed thermo-luminescence and infra-red-stimulated luminescence dating of sediments. We conclude that the Jiahu site dates from roughly 7000 to 5500 B.C. (Yang et al. 2005). The first or early phase of occupation at Jiahu, 7000–6500 B.C., is earlier than the Peiligang culture. The second and third phases at Jiahu date from 6500–6000 and 6000–5500 B.C., roughly contemporary with the Peiligang culture. In the rest of this chapter we discuss information obtained from the Jiahu site about the environment and subsistence practices, settlement organization, social differentiation, craft production, and rituals. We conclude with some especially important discoveries from Jiahu. ~|~

Environment and Climate of the Jiahu Culture

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “Therefore, we should consider the paleoenvironment while analyzing the settlement pattern of the Jiahu site. The temperature on earth has been through a process of rise and fall since the early Holocene. Recent research in China combines data from pollen analysis, paleozoology, paleobotany, soil magnetic susceptibility, changes in sea level and lake levels, and oxygen isotope (ð 18 O) values from the Dunde ice core in the Qilian mountains of Gansu province for the past 10,000 years (Shi and Kong 1992). This work has refined the climatic sequence of the Holocene from around 8500–3000 years ago (c.6550–1050 B.C.). The period relevant to our discussion here covers the period from around 8500 to 7200 years ago (c.6550–5250 B.C.). 1 The occupation of Jiahu begins just before and continues through the first of the four major climatic periods – the period of unstable, fluctuating temperatures, around 8500–7200 years ago. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

There is evidence for a large quantity of tropical and subtropical animals and plants during the later portion of the first period. The climate was warmest and most humid during the second period. A large quantity of fauna and flora which prefer a warm and humid climate was found in this period. At the same time, the deciduous broadleaf forest of the northern warm temperate zone expanded northward. ~|~

“The small increase of dry- and cold-resistant elements contemporary with the third or final phase of occupation at Jiahu was probably associated with a temperature decline somewhere around 7800 years ago (c.5850 B.C.). This is also reflected in the Dunde ice core record (Kong et al. 1982). Glaciers in Alaska, Scandinavia, New Zealand, and the Himalaya–Karakoram area also expanded (Rothlisberger 1986). This global temperature decline probably posed problems for human settlement. Similarly, pollen data from Jianhu County in Jiangsu shows that the average temperature around 8500 to 8000 years ago (c.6550–6050 B.C.) was 1.4–1.7̊C higher than today. It gradually decreased until around 7600 years ago (c.5650 B.C.), when it was 0.1̊C lower than today (Tang and Shen 1992). ~|~

“According to our radiocarbon dating results, Jiahu village was first occupied during, or immediately prior to, the first climatic period described above. Within that climatic period, we have identified three different phases of climatic conditions at the site: early, middle, and late. Evidence for the cooler first phase was the discovery of bone from a variety of sable, "zidiao" (apparently "Martes zibellina" in the earliest deposits at Jiahu, representing the phase of lowest temperature at the site, around 8900–8700 years ago (c.6950–6750 B.C.). It seems that the climate fluctuated more rapidly during the first phase at Jiahu. Then the temperature continued to rise, and rainfall increased. Pollen analysis suggests that the climate during much of the occupation of Jiahu was similar to today ’ s Jiang–Huai area. The temperature was about 1̊C higher than today but still fluctuating. According to the radiocarbon and stratigraphic data from the Jiahu site, we conclude that the village was abandoned after a flood around 7400 years ago (c. “5450 B.C.). ~|~

“Therefore we have a basic understanding of Jiahu ’ s natural environment and can picture it as follows. Around the village was a grassland consisting of plants from the “Artemisia “genus as well as Asteraceae and Chenopodiaceae families, along with raccoon dogs (“Nyctereutes procyonaides”), sika deer (“Cervus nippon”) and wild rabbits occasionally running on it. In the neighboring hills, there were sparse deciduous broadleaf forests consisting of oak, chestnut, and walnut trees. Under the trees or besides ditches and cliffs, bushes such as sour jujube (“suanzao “) and tamarisk (“guailiu “) grew. Wild pigs and muntjac (genus “Muntiacus”) lived in the forest and frightened ring-necked pheasants from time to time. Aquatic plants such as lotus and sedges flourished on the surfaces of the lakes around the village. Large amounts of fish, clams, spiral shells, tortoises, soft-shelled turtles, and alligators lived on the riverbank, river deer and elk played and drank. Redcrowned cranes and swans danced and sang. A few elm, willow, mulberry, and plum trees occasionally rustled in the wind. Ancient people cultivated rice on land around the village. ~|~

Climatic phases for the Jiahu site: 1) Late phase 6000–5500 B.C., warmer and wetter; 2) Middle phase 6500–6000 B.C., warmest and wettest; 3) Early phase 7000–6500 B.C., transition from dry, cold to warm, wet beside the waters.

stone sickle

Jiahu Life

Based on an examination of 238 skeletons Harvard forensic archeologist Barbara Li Smith concluded that the Jiahu villagers enjoyed fairly good health. The average age of death was around 40, late for Neolithic people. Sponge lesions on the skull indicate that anemia and iron deficiency were a problem. Hole bone lesions from disease and parasitic infections are rare.

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “The rich natural environment around Jiahu village had a great impact on subsistence practices and the development of human society. Yu and Zhang (1992) pointed out that subsistence techniques, community organization, and worldview are interrelated in adaptation to the environment. It is important to consider changes in the nature of the settlement and the ultimate abandonment of the site. As an example, we found that a decrease in cultural remains in an eastern area was probably associated with expanding bodies of water to the east of the village. ~|~

“We also should consider the interrelationship of the environment and society. In earlier times, changes in the environment greatly affected subsistence patterns. When the environment is very good, however, people ’ s needs are so easily fulfilled that they do not have to work hard for a living, and the development of human society may slow. Society could only develop further when the natural environment was suitable for living and there were forces to push humans to adapt more effectively to nature through hard work. Of course, the development of human society also relies on the accumulation of experience and wisdom in adapting to the environment over a long period of time. The agricultural revolution in more than one area of the world was a huge factor in social development – for example the domestication of wheat, barley, and goat in West Asia (Mesopotamia), and the domestication of rice, millet, and pig in East Asia. These changes were like the two feet of a giant and the two wings of a big bird which drove human society to develop quickly. ~|~

“The development of an agricultural economy probably resulted from population growth along with a decline in some natural resources. The development of farming complemented hunting and gathering, rather than replacing it (Zhao 2005). The rice agriculture of the Jiahu people appeared and developed at the same time as the rice agriculture of the Pengtoushan culture and the millet agriculture of the Peiligang and Cishan cultures. According to the analyses of agricultural tools, however, the development of Jiahu rice agriculture was faster than that of Pengtoushan. The natural environment of the Yangzi river basin has been much better than that of the Huai river basin since the beginning of Holocene. The Jiahu people therefore could have had satisfactory rice harvests only through a fair amount of deliberate management of their environment. In addition, the natural environment around the village could support hunting and animal husbandry. The big lakes provided resources for fishing, and collecting both terrestrial and aquatic edible plants was possible. ~|~

Food, Rice and the Jiahu Culture

Jiahu villagers fished for carp; hunted crane, deer, hare, turtle and other animals; and collected a wide variety of wild herbs and vegetables such as acorns, chestnuts and broad beans and possibly wild rice. They also possessed domesticated dogs and pigs. Among the tools and utensils unearthed at Jiahu are three-legged cooking pots, arrows, barbed harpoons, stone axes, awls, and chisels.

Zhao Zhijun wrote: “The quantitative analysis of plant remains recovered by floatation from the Jiahu site, dated to ca. 8,000 cal. B.P., revealed that the subsistence of the Jiahu people mainly relied on fishing/hunting/gathering, while the products of rice cultivation and animal husbandry were only a supplement to their diet.

Baozhang Chen and Qinhua Jiang wrote in Economic Botany: “Until now, most of the early rice remains in China were found in the middle to lower reaches of the Yangtze River drainage. Recently, rice remains earlier than 8000 B.P. were found from Jiahu site (8942-7801 B.P.) in Wuyang County of Henan Province, central China. This is the earliest cultivated rice found at this latitude (33̊37'N), which is far outside the current distribution of wild rice species. The discovery is of great implications. It suggests that central China may be one of the centers of early rice domestication. [Source: “Antiquity of the Earliest Cultivated Rice in Central China and its Implications, by CHEN, Baozhang and JIANG, Qinhua, Economic Botany Vol. 51, No. 3, Jul. – Sep., 1997 New York Botanical Garden Press]

Jiahu Settlement Organization and Houses

bone arrowheads

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “The excavation area of the Jiahu site can be divided into five areas from west to east. In each area, we found trash pits, burials, storage pits, and pottery kilns. Research on these remains shows that there is a distinct difference between the early climatic phase and the two later climatic phases (middle and late) defined above. So I will refer to just two phases of social development at the Jiahu site in the remainder of this chapter, as early and late. As discussed below, in the early phase, living areas and burial areas were mixed together, although the distribution shows some houses in groups. It seems that there was no clear layout, suggesting rather random placement of constructions and other features. From the layout of the middle–late phase, we can feel the pulse of development. The village has a more orderly appearance, given what looks like a planned layout for houses and burials. Also, the burial area was separated from the living area, a separation that became clearer over time, from the middle to late phase, as if people followed standard rules. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

“Excavation of the residential areas showed that there are three kinds of houses at Jiahu: semi-subterranean ("bandixue"), surface-level, and pile-dwellings (stilt-style "ganlanshi"). Most of the houses have single rooms and are semisubterranean. There also are a few structures with more than one room. ~|~

“The early phase layout was relatively simple with few living and burial areas, although each of the five areas mentioned above were used. Only the second area in the west had a more complete arrangement with a greater density of remains. We discovered seven houses (six semi-subterranean, one stilt style), surrounded by 26 burials, 30 trash pits and two pottery kilns. There was an increase in the quantity of structures in this area from the early phase to the late phase. The biggest house of the second group in the western area, F17, is 24 square meters in size. It was originally a single space and became a building with multiple rooms after several extensions. The house is located in the center of the cluster. All of the other houses in the group face the center. The arrangement was rather disordered and displayed a lack of unity. The pattern is a distinct contrast to the careful spatial arrangements at the sites of Jiangzhai, Banpo, Yuanjunmiao, and Dahecun in the Yangshao period. ~|~

“More burials were distributed between the houses in this area, especially around F17. On the one hand, the reason for the large number of burials may be that this structure was a center of the houses in the area. On the other hand, F17 was extended over time from one single room to four. It represents a larger capacity and a longer period of use than at the surrounding houses. The deceased in the neighboring burials were probably the residents of that house. At this time, therefore, burial and living areas were located in the same areas. Separate, public burial grounds had not been developed. We discovered large amounts of pottery sherds, tools, and animal and plant remains in the deposits under those houses. These remains probably were refuse from the structures and help us understand their functions. Most of the structures have associated broken pottery vessels used for cooking and eating, except for F38, the stilt-style structure. We can interpret them, therefore, as dwellings. There are no remains inside structure F38 or in the deposits below it to indicate a dwelling. The two big houses, F5 and F17, contain a larger number and more types of pottery vessels. Tools used in production of goods also were discovered there. This also reveals a functional difference between big and small structures during the early phase. It appears that production activities were carried out in the big houses. The houses around F17 probably formed a group in the village. ~|~

“Do the five spatial groups for the early phase represent five families or five clans? Forty-two burials were discovered in the first phase. They are more dispersed and all located in the western area of the site. On the basis of this pattern, they can be divided into two groups: Group A contains 26 burials and Group B contains 16 burials. The distance between the two groups is about 6–13 meters. These two groups of burials and houses could belong to two families who lived on the site at the same time. It is also possible that the two families formed a clan community. ~|~

“Two pottery kilns ("yao") from the early phase were discovered at Jiahu, and they were located on either side of the village. Both kilns (Y1 and Y2) are located around the houses of the second spatial group in the western area. It is apparent that a special area for pottery-making had not developed and that production was at the household level. ~|~

Peiligang Fish Farms and Silk

Some of the oldest known silk fibers have been found in Jiahu. Archaeology magazine reported in 2017:” Soil samples taken from beneath skeletons in two tombs that date back 8,500 years reveal traces of silk proteins, indicating that the deceased may have been dressed in silk garments when they were buried. This new evidence pushes back the first known silk production technology by nearly 3,500 years. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2017]

Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: “Members of northern China’s Peiligang culture practiced aquaculture well before the domestication of fish in medieval Europe. By measuring teeth from common carp remains excavated at the Neolithic site of Jiahu, an international team of researchers estimated the body sizes of the fish. Comparing them with carp populations reared in modern Japanese fisheries, they found that the ancient specimens represent both immature and mature fish. This suggests that, by about 8,000 years ago, Jiahu residents had begun to raise carp in controlled channels, where the fish spawned naturally and were harvested in the autumn. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2020]

“A dramatic increase in burials identified at Jiahu around this time indicates that the settlement had grown, explains archaeologist Junzo Uchiyama of the Sainsbury Institute. “It’s possible to assume that carp aquaculture was developed in response to the increase of population,” he says. This innovative approach to food production might have also enabled the Peiligang to expand, as the number of sites associated with the culture increased after 8,300 years ago.

Late Jiahu Villages and Houses

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “During the middle–late phase, the number of houses and burials had dramatically increased, reflecting the spatial expansion of the village and population growth. There also is an increase in the number of houses from the middle to late phases. On the basis of the numbers of houses and burials, we conclude that there were about 160–260 residents of Jiahu village at the time. We also found a change in settlement pattern from the early phase. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

“The layout of the late phase demonstrates more planning. According to the distribution of houses, trash pits, and burials during this phase, the living and burial areas of Jiahu village, which had been intermixed in the early phase, had now developed into a pattern with separate living, working, and burial areas. ~|~

“The 31 houses discovered in the living areas for this phase can be divided into six groups. These six groups of houses represent a social structure involving several extended families that formed a clan. Each house group corresponds to a burial area separated from residential areas. Long-term family burial grounds appeared and an independent public cemetery developed. If each group of houses and burials can be regarded as a family, we can estimate that more than two, perhaps even five, clans coexisted in the village during each phase. Therefore we conclude that there were three forms of social organization in the village: clan, family, and household. In addition, we found that these house groupings were not completely contemporary with the burial areas. Use of the burial areas began slightly earlier than the living areas and lasted longer, during the whole middle–late phase. So the use of these functional areas was not planned but gradually developed with the growth of the village. ~|~

“During the middle–late phase, pottery kilns were all located around houses. It appears that each spatial group had its own pottery-making area. This change would have raised the level of production and provided a foundation for further development of pottery production into independent areas with specialization of labor. ~|~

“In addition, we discovered two ditches that we interpret as moats ("haogou") in the southeast and southern parts of the site. Artifacts in the deposits of these ditches belong to the second and third phases, suggesting that the formation, utilization, and abandonment of the moats all occurred during the middle–late phase. Considering the circular moats commonly seen in other Neolithic village sites, including those in the Yangshao and Longshan periods, it is likely that circular moats existed at Jiahu village. ~|~

“The orientation of house doors and the remains of the circular ditches indicate that the village was inward-facing and enclosed. It was not as uniform as the roughly contemporary villages from the Xinglongwa culture and from the Yangshao period. The circular moat from the second phase at Jiahu village was the predecessor of the inward-facing and enclosed moat-style village from the Yangshao period. ~|~

“We also discovered three holes with fired clay forming a row in a north–south direction in the western residential area of the site; they appear to be large postholes lined with fired clay for more support. We believe they are part of a very big central house, located right between the eastern and western groups of houses. Also, the land between the two house groups probably functioned as a central square, as seen at the Yangshao site of Jiangzhai. We propose that the middle–late big central house was an indoor workplace for clan members. ~|~

“It also is significant that the early phase had a mixture of burial and living areas that was different in layout from other relatively early Neolithic villages. For example it was different from the "jushi zang", or “indoor burial” style of the contemporary Xinglongwa culture, and the distinctive burial areas of the Peiligang period. It could represent a transitional phase for the Neolithic period. Furthermore, the circular moat that appeared during the second phase at Jiahu most likely served a defensive function for village members.” ~|~

Evidence for Social Differentiation in Jiahu Houses

Peiligang pottery

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “Changes in house architecture provide information about progress in social development towards civilization (Morgan 1981, 1985). The residential area at Jiahu reveals a preliminary division of labor and functional differentiation. Does this social division represent social stratification? It seems not, since the remains from Jiahu indicate that the society was still in a stage of relative equality. [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

“First, there are some differences between spatial groups. For example, we discovered more houses and artifacts in the second group in the western area for the early phase. It seems that there were some differences between these groups, but the differences were not enough to indicate a clear social division in the village. But in one group several houses surround a central house. This demonstrates that the central house must have had a special function, perhaps relating to production, since more production tools were found here than in the surrounding small houses. The difference between these houses represents an initial social division of labor. ~|~

“As discussed, the central house (F17, in the second group of the western area in the early phase) was enlarged over time, and it contained tools not only for daily use but also those used to produce other objects. It is possible that the house functioned as a center of tool production. The people living in a group of houses probably belonged to a clan consisting of several families. They lived around the house and worked on a series of important production activities. The person who lived in the house would have been no ordinary person but the chief of the clan or the leader of the village. The big house of Jiahu village during the late phase was probably meant for an extended family, so it was a living and an economic unit. It was different from the small house for a nuclear family or a married couple. This large house should therefore not be associated with greater wealth. In addition, big houses at Jiahu are scattered and not in the same part of the site. Their appearance could reflect some changes in marriage patterns and the structure of social life. ~|~

“In addition the single room structure F1, dating to the late third phase at the site, is almost 50 square meters. Why did people build such a large house? It was probably because F1 functioned as the central house of the clan, so it required a larger capacity. Furthermore, its size shows that construction techniques during the late phase had reached a high level. It also reflects the development of social production implying an increasing need for a production space associated with the clan. Analyzing these bigger and more complicated houses can show that the social division of labor had been developing during the Jiahu period, but not social stratification. The society was still in the stage of relative equality.” ~|~

Population Movements in the Jiahu Area

Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology”: “In order to find possible evidence for prehistoric migrations and demographic history, we used the strontium isotope technique to analyze 26 human and animal bones (including teeth) from the site. The results suggest that 5 of the 14 human individuals tested immigrated from other places. Furthermore, the frequency of migration increased from the first to the third phase (Yin 2008 ; Yin et al. 2008). Therefore, population flow between villages was very common during that period. In addition, this population movement between villages mostly involved females, suggesting a marriage pattern involving exogamy (Yin et al. 2008). [Source: “The Jiahu Site in the Huai River Area” by Zhang Juzhong and Cui Qilong, A Companion to Chinese Archaeology, edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 thirdworld.nl ~|~]

As for the origin of the foreigners, it is unlikely that they came from a distant area, because of the limitations of transportation methods at the time. They probably came from villages in the region near the Jiahu settlement. The known sites are less than 100 kilometers away from Jiahu, and those people could have reached Jiahu in about three days using the transportation methods available at the time.

“Compared to hunting and gathering, agriculture increased the carrying capacity of the land. During the middle Jiahu phase, rice cultivation was fairly developed. Farmers made a large labor investment and were therefore motivated to reduce fallow periods in their permanent settlements. Anthropological data show that women in farming societies tend to have more children in comparison to hunter-gatherer societies (Wang 1997). Therefore, the increased carrying capacity and the development of permanent settlements provide good conditions for population growth. People also wanted more children to provide more labor for farming. Eventually the population exceeded the carrying capacity, causing population pressure. Beginning in the middle phase, the number and density of remains in the Jiahu village increased rapidly, reflecting population growth. When the village no longer satisfied the needs of the inhabitants, people must have moved to other places with more abundant resources. The contemporary villages around the Jiahu site were probably the ideal destinations. ~|~

Image Sources: Jiahu Culture map, Metroplitan Museum of Art; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021