ANCIENT FOOD AND DRINKS IN CHINA

zhou dynasty pig

The earliest identified crops in China were two drought-resistant species of millet in the north and rice in the south (see below). Domesticated millet was produced in China by 6000 B.C. Most ancient Chinese ate millet before they ate rice. Among the other crops that were grown by the ancient Chinese were soybeans, hemp, tea, apricots, pears, peaches and citrus fruits. Before the cultivation of rice and millet, people ate grasses, beans, wild millet seeds, a type of yam and snakegourd root in northern China and sago palm, bananas, acorns and freshwater roots and tubers in southern China.

The earliest domesticated animals in China were pigs, dogs and chickens, which were first domesticated in China by 4000 B.C. and believed to have spread from China across Asia and the Pacific. Among the other animals that were domesticated by the ancient Chinese were water buffalo (important for pulling plows), silkworms, ducks and geese.

Wheat, barley, cows, horses, sheep, goats and pigs were introduced to China from the Fertile Crescent in western Asia. Tall horses, like we are familiar with today, were introduced to China in the first century B.C. In the late 2010s, in a tomb excavated in eastern China’s Jiangsu province, archaeologists found a jar filled with eggs dating back to the Spring and Autumn Period (770–ca. 475 B.C.), making them at least 2,500 years old. Only shells remain. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2019]

The ancient Chinese made beer from Broomcorn, millet, barley, Job’s tears and tubers. Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “This ancient Chinese beer recipe probably produced an interesting bouquet. The ingredients were identified from residues found in a variety of clay vessels, including a funnel, that may have comprised a “beer-making toolkit” from a 5,000-year-old site in Shaanxi. The find is also the earliest known identification of barley in the country, suggesting the grain was introduced for beer production rather than as food. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2016]

The Book of Rites, a Chinese history book compiled in the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. - 9), put melons, apricots, plums and peaches among the 31 categories of food favored by aristocrats of the time. It said people in the Zhou Dynasty had also learned to grow fruit trees in orchards. A poem in the “Book of Songs”, a collection of poetry from the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century -771 B.C.)to the Spring and Autumn Period (770 – 475 B.C.), says food kept in “ling yin” — meaning cool places — will stay fresh for three days in the summer. [Source: Zhang Xiang, Xinhua, November 20, 2010]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; FIRST CROPS AND EARLY AGRICULTURE AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WORLD'S OLDEST RICE AND EARLY RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT FOOD, DRINK AND CANNABIS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINA: THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WRITING? factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC CHINA factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000-5700 B.C.): CHINA’S EARLIEST CULTURE AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000 B.C. to 5700 B.C.): HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WINE AND SOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST FLUTES, WRITING, POTTERY AND ANIMAL SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; YANGSHAO CULTURE (5000 B.C. to 3000 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; KUAHUQIAO AND SHANGSHAN: THE OLDEST LOWER YANGTZE CULTURES AND THE SOURCE OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DOMESTICATED RICE factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC TIBET, YUNNAN AND MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Story of Rice” by Xiaorong Zhang Amazon.com ; “The Secret History of Food: Strange but True Stories About the Origins of Everything We Eat” by Matt Siegel, Roger Wayne, et al. Amazon.com; “Liangzhu Culture” by Bin Liu, Ling Qin, et al. Amazon.com; “Qijia (Jades of the Qijia and related northwestern cultures of early China, ca. 2100-1600 BCE” by Dr. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson and Gu Fang Amazon.com ; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com; “Life in Ancient China (Peoples of the Ancient World)” by Paul Challen Amazon.com ; "China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com ; "The Cambridge Illustrated History of China" by Patricia Buckley Ebre Amazon.com

Food and Drink in China, 3000 Years Ago

What did Chinese people eat 3,000 years ago? How did they cook? What kind of tableware or cooking utensils did they use? The increasing number of archaeological finds over the past few decades, especially the discoveries of ancient bronze wares, have shed new light on these questions. Many of the unearthed bronze wares were found with the remains of food or wine. [Source: China.org, March 13, 2003, This article first appeared in 2003's third issue of Collections, a Chinese language monthly magazine ~]

According to China.org: “People of the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties highly valued their way of dining. Delicious and nutritious food was regarded as the basis of ordinary life. Inscriptions engraved on ancient bronze items showed rice and wheat were the major staple foods since the Shang Dynasty. Shi Jing (The Book of Songs), one of the seminal works of the Chinese civilization, featured records of growing grain as well as grain processing. According to Li Ji (Records of Ritual), one of the five early Chinese classics, people at that time had begun to make cake with flour. Generally, the staple food was either boiled in a li or steamed in a yan (See Cooking Below). ~

“As far as meat went, archaeological findings showed Shang people enjoyed a wide variety of animals including horse, cow, chicken, pig, sheep and deer. Of course, only the upper-class was able to enjoy these delicacies. For common people, however, fish was probably the best food they could attain. Over a dozen kinds of fish were mentioned in Shi Jing. Fish-shaped jade items were often excavated, which proved the prominent role of fish in people's daily diets. ~

“People of the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties set forth culinary standards that are still followed today, such as the practice of cutting food into bite size pieces during preparation and not at the table. They stressed both the food and the culinary vessels must be cleaned completely before cooking. They also decreed that harmony among ingredients with respect to their size, shape, fragrance, taste and texture should be the goal of the chef. Diets should be changed with different seasons. To gain a balanced diet, vegetables and fruits were assorted with the main dishes. Seasoning varieties were also dazzling with sweet, hot, sour or spicy flavours, which made the dish tasty and healthy. Sauces made of meat, fish and oyster were also popular. ~

“On the imperial palace menu was the drinking side of the dining experience.Artifacts produced during the Shang Dynasty consisted mainly of wine vessels. It shows the important role wine drinking played in the lives of Shang people. According to historical documents, the best wine at the time was made with millet. Historians argued that the imperial class was so fond of a drop it led to the collapse of the Shang Dynasty. Rulers of the Western Zhou Dynasty learned from Shang people and restricted drinking. ~

“Ancient Chinese were also concerned about the freshness of food and worked out effective ways to preserve food. They built large underground "Lingyin" (cold storage) areas, which were chilled enough to keep food fresh in winter. Salting meat, fish and pickling vegetables was another effective method.” ~

World's Oldest Marijuana Found in Northwest China

Cannabis

Nearly a kilogram of still-green marijuana was found in a 2,700-year-old near Turpan in northwest China. Jennifer Viegas of NBC News wrote: “Nearly two pounds of still-green plant material found in a 2,700-year-old grave in the Gobi Desert has just been identified as the world's oldest marijuana stash, according to a paper in the latest issue of the Journal of Experimental Botany. A barrage of tests proves the marijuana possessed potent psychoactive properties and casts doubt on the theory that the ancients only grew the plant for hemp in order to make clothing, rope and other objects. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, NBC News, December 3, 2008 =]

“They apparently were getting high too. Lead author Ethan Russo told Discovery News that the marijuana "is quite similar" to what's grown today. "We know from both the chemical analysis and genetics that it could produce THC (tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase, the main psychoactive chemical in the plant)," he explained, adding that no one could feel its effects today, due to decomposition over the millennia. =

“Russo served as a visiting professor at the Chinese Academy of Sciences Institute of Botany while conducting the study. He and his international team analyzed the cannabis, which was excavated at the Yanghai Tombs near Turpan, China. It was found lightly pounded in a wooden bowl in a leather basket near the head of a blue-eyed Caucasian man who died when he was about 45. "This individual was buried with an unusual number of high value, rare items," Russo said, mentioning that the objects included a make-up bag, bridles, pots, archery equipment and a kongou harp. The researchers believe the individual was a shaman from the Gushi people, who spoke a now-extinct language called Tocharian that was similar to Celtic. =

“Scientists originally thought the plant material in the grave was coriander, but microscopic botanical analysis of the bowl contents, along with genetic testing, revealed that it was cannabis. The size of seeds mixed in with the leaves, along with their color and other characteristics, indicate the marijuana came from a cultivated strain. Before the burial, someone had carefully picked out all of the male plant parts, which are less psychoactive, so Russo and his team believe there is little doubt as to why the cannabis was grown. =

“What is in question, however, is how the marijuana was administered, since no pipes or other objects associated with smoking were found in the grave. "Perhaps it was ingested orally," Russo said. "It might also have been fumigated, as the Scythian tribes to the north did subsequently." Although other cultures in the area used hemp to make various goods as early as 7,000 years ago, additional tomb finds indicate the Gushi fabricated their clothing from wool and made their rope out of reed fibers. The scientists are unsure if the marijuana was grown for more spiritual or medical purposes, but it's evident that the blue-eyed man was buried with a lot of it. "As with other grave goods, it was traditional to place items needed for the afterlife in the tomb with the departed," Russo said. The ancient marijuana stash is now housed at Turpan Museum in China. In the future, Russo hopes to conduct further research at the Yanghai site, which has 2,000 other tombs.” =

Uses of Cannabis in Ancient China

According to Archaeology magazine:Cannabis was an important part of Central Asian rituals. Researchers have detected trace amounts of the drug on several 2,500-year-old wooden braziers from the Jirzankal cemetery in far western China. This is the oldest scientifically verified evidence of cannabis smoking. The samples contained higher levels of psychoactive chemicals than most wild cannabis varieties, suggesting that locals may have cultivated the plant for its mind-altering effects. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

A tomb in the Jiayi Cemetery “it’s clear that the plant carried special ritual or medicinal importance to his people. His body had been wrapped in a “shroud” of 13 cannabis plants, fanning out across his torso, around 2,500 years ago. Most of the flowers had been removed, but those that remain suggest he was buried in the late summer. — Samir S. Patel, [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

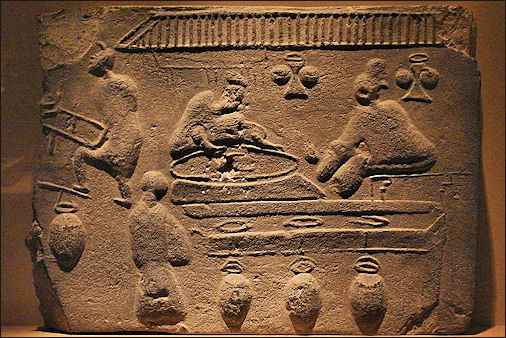

Cooking in China, 3000 Years Ago

Shang-era bronze ding (cooking vessel)

According to China.org: “The Chinese have always considered cooking to be one of the first steps out of savagery into civilization. Legend has it that cooking and food were so important in ancient China that Emperor Tang, founder of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), appointed as his prime minister Yi Yin, a renowned cook who created China's cooking culture.[Source: China.org, March 13, 2003 ~]

“Historians had argued that Shang people living over 3,000 years ago had mastered cooking techniques like steaming, stir-frying, frying and deep-frying. Archaeologists have found that in addition to pottery vessels, a dazzling variety of bronzes were once popular cooking utensils and tableware among the upper-class, which played a significant role in the study of Chinese culinary history. ~

“According to Li Xueqin, an expert on Chinese bronzes at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, these pieces were regarded as sacred vessels and only used during complex ritual ceremonies. Generally, the bronze vessels are divided into four categories according to their uses: cooking vessels, food containers, wine vessels and water vessels. As Li wrote in his works Chinese Bronzes, the ding was one of the most important types of bronzes used for cooking meat. It is either three-legged and round or four-legged and rectangular, which was designed to elevate the vessel and provide a space underneath for a fire to be built. The li was another kind of cooking vessel characterized by its pouch-like hollow legs. Liquid could flow to the legs and be heated more rapidly. ~

“The ding and li often came with spoons featuring a long handle and a sharp tip, which was used for picking meat out of the vessel. The yan was a steamer. It has pouch-like legs that can be filled with water like a li. Its upper part was like that of a ding. A rack was connected to the base so it could hold the food to be steamed. Historical documents showed each type of vessels was designed for a specific kind of food and could not be misused. As for the bronze wine vessels, the jue and gu were the most common. The jue was an odd-looking wine cup with three long, flat, pointed legs. It had a handle and a long spout with an upward tail that served as a counterweight. ~

“The most peculiar features were two small umbrella-like columns on the top. Research shows the two columns might have been used for hanging spice bags, which were immersed in the wine. Another assumption is that since men did not shave their beards at that time, the columns were used to divide their beards and prevent them from being stained by the wine. ~

“In the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties, the bronze wares were not only used for cooking, but were an indication of social status. Often, a series of ding of varying sizes showed the rank of the owner, depending on how many pieces were in a set. According to historical documents, emperors in the Western Zhou Dynasty could use nine ding, dukes could only use seven, senior officials five and lower-ranking officials three. Commoners were forbidden to use them and violators could be punished by death.” ~

3,000-Year-Old Cellar with Melons and Apricots Found in North-Central China

In November 2010, Chinese archeologists announced they had found remains of ancient fruit — mostly well-preserved apricot and melon seeds — in a 3,000-year-old cellar in China’s Shaanxi Province. Zhang Xiang of Xinhua wrote: “The cellar was a rectangular pit about 105 centimeters long, 80 centimeters wide and 205 centimeters deep, said Dr. Sun Zhouyong, a researcher with the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archeology. Sun and his colleagues found the pit in 2002, about 70 centimeters underground the Zhouyuan site, ruins of Western Zhou dynasty (1046-771 B.C.)100 kilometers from Xi’an. After eight years of research, they concluded it was a cellar used to preserve fruits for aristocrats. [Source: Zhang Xiang, Xinhua, November 20, 2010 ^]

“In each corner of the pit, Sun and his colleagues found a little round hole. “We assume the cellar had something like a shade that was fixed on the four holes but had decayed over the years.” Inside the cellar the researcher could see, even with naked eye, huge piles of nuts and seeds. “We sorted them out with care, and found about 500 apricot nuts — 108 of which were complete with carbonized pulp, at least 150 melon seeds and 10 plum seeds,” said Sun. They also found millet and grass seeds. “Most of the seeds were intact and very few were carbonized,” said Sun. “It was so amazing that scientists who conducted lab work suspected they were actually put away by rodents in more recent times.” ^

“Sun and his colleagues sent three apricot nuts to Beta Analytic in Florida, the United states, last year for carbon 14 test to determine their age. “The test results indicated they were about 3,000 years old, dating back to a period between 1380 B.C. and 1120 B.C.,” said Sun. “Seemingly the fruits had been stored in an acidic and dry environment, so dehydration was extremely slow and the nuts were not carbonized even after so many centuries.” ^

“Zhouyuan site, where the cellar was unearthed, was believed to be a dwelling place for Duke Danfu, an early leader of the Zhou clan. It was known as the cradle of the Western Zhou Dynasty, one of the earliest periods of China’s written history. “Presumably, the aristocrats had stored fruits in their family cellar,” said Sun. The cellar, with roughly 1.7 cubic meters of storage, could store up to 100 kilograms of fruits, he said. ^

2,500-year-old Noodles, Cakes and Porridge Found in Xinjiang

millet cake

In 2010, Jennifer Viegas wrote in Discovery News, “noodles, cakes, porridge, and meat bones dating to around 2,500 years ago were unearthed at a Chinese cemetery, according to a paper that appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Since the cakes were cooked in an oven-like hearth, the findings suggest that the Chinese may have been among the world's first bakers. Prior research determined the ancient Egyptians were also baking bread at around the same time, but this latest discovery indicates that individuals in northern China were skillful bakers who likely learned baking and other more complex cooking techniques much earlier. [Source: Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News, November 19, 2010 +]

"With the use of fire and grindstones, large amounts of cereals were consumed and transformed into staple foods," lead author Yiwen Gong and his team wrote in the paper. Gong, a researcher at the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team dug up the foods at the Subeixi Cemeteries in the arid Turpan region of Xinjiang. "As a result, the climate is so dry that many mummies and plant remains have been well preserved without decaying," according to the scientists, who added that the human remains they unearthed at the site looked more European than Asian. +\

“The individuals may have been living in a semi agricultural, pastoral artists' community, since a pottery workshop was found nearby, and each person was buried with pottery," Viegas wrote. “The archaeologists also found bows, arrows, saddles, leather chest-protectors, boots, woodenwares, knives, an iron aw, a leather scabbard, and a sweater in the graves. But the scientists focused this particular study on the excavated food, included noodles mounded in an earthenware bowl." “The noodles were thin, delicate, more than 19.7 inches in length and yellow in color," according to Lu and his colleagues. "They resemble the La-Mian noodle, a traditional Chinese noodle that is made by repeatedly pulling and stretching the dough by hand."

“Ciux jak The food also included ‘sheep's heads (which may have held symbolic meaning), another earthenware bowl full of porridge, and elliptical-shaped cakes as well as round baked goods that resembled modern Chinese moon cakes. Chemical analysis of the starches revealed that both the noodles and cakes were made of common millet. The scientists next put new millet through a barrage of cooking experiments to see if they could duplicate the micro-structure of the ancient foods, which would then reveal how the prehistoric chefs cooked the millet. The researchers determined that boiling damages the appearance of individual millet grains, while baking leaves them more intact. The scientists therefore believe the millet grains in one bowl were once boiled into porridge, the noodles were boiled, and the cakes were baked."

"Baking technology was not a traditional cooking method in the ancient Chinese cuisine, and has been seldom reported to date," according to the authors, who nevertheless believe these latest food discoveries indicate baking must have been a widespread cooking practice in northwest China 2,500 years ago. +\

“The discoveries add to the growing body of evidence that millet was the grain of choice for this part of China. Houyuan Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Geology and Physics, along with other researchers, unearthed millet-made noodles dating to 4,000 years ago at the Laija archaeological site, also in northwest China. Gong and his team point out that millet was domesticated about 10,000 years ago in northwest China and was probably a food staple because of its drought resistance and ability to grow in poor soils. +\

2,400-Year-Old Dog Bone Soup Found in Xian

In a Warring States tomb in Shaanxi Province a team of researchers found a soup containing what they believe to be dog bones. One researcher sampled the what was said to be the world's oldest soup, which is cloudy and green due to the bronze vessel it was stored in for more than 2,000 years. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January/February 2012]

In December 2010 AFP reported: Chinese archaeologists announced they had discovered a 2,400-year-old pot of bone soup near Xian. The soup and bones were discovered in a small, sealed bronze vessel in a tomb being excavated to make way for the extension of the airport in Xian. The liquid and bones in the vessel had turned green due to the oxidation of the bronze. It's the first discovery of bone soup in Chinese archaeological history," the Global Times quoted Liu Daiyun of the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology as saying. "The discovery will play an important role in studying the eating habits and culture of the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.)." [Source: AFP, December 13, 2010]

According to crienglish.com: “The soup likely contains the foot bone, vertebra and rib of a chicken or small sheep, according to the archeologists. The soup appears turbid, with green bronze scraps floating on the surface, and the bones partially tinged with green color. Along with the bronze tripod cooking vessel, another bronze ware was unearthed containing a “mysterious” liquid thought to be alcohol. Archaeologists speculated it was a custom of that time to bury soup and alcoholic drinks along with the dead. The miraculous preservation of the liquids is attributed to good sealing and dry conditions inside the tomb, according to the experts. The bronze wares were kept in a niche that was much drier than the bottom area of the tomb, the report said.” [Source: crienglish.com]

Liu told the Times of London took the lid off the three-legged and was amazed to find it was half-full of liquid. “I was really shocked." he said. “My guess is the liquid did not evaporate because of the lid and the because the tomb had been tightly sealed for more than 2,000 years." Archaeologists also dug up another bronze pot that contained an odorless liquid believed to be wine in the tomb, which could belong to either a member of the land-owning class or a military officer, the report said

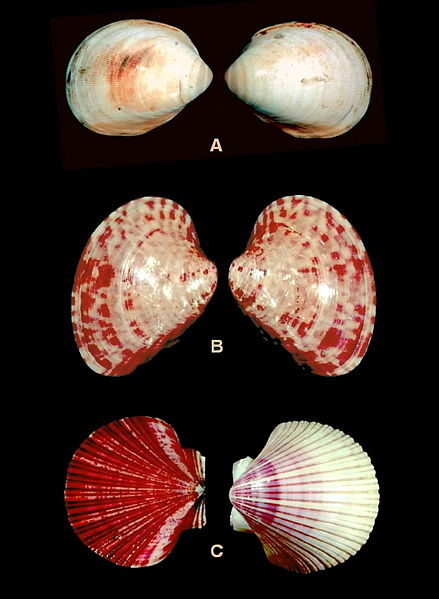

2000 Years Ago, Chinese Emperors Living Far From the Sea Dined on Sea Snails and Clams?

In October 2010, Chinese scientists announced that ancient Chinese emperors living in inland China may have dined on seafood that came from the eastern China coast more than 1,600 kilometers after investigating an imperial mausoleum that dates back 2,000 years. “We discovered the remains of sea snails and clams among the animal bone fossils in a burial pit,” Hu Songmei, a Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology researcher told Xinhua. “Since the burial pit appears to be that of the official in charge of the emperor’s diet, we conclude that seafood must have been part of the imperial menu,” Hu said. [Source: Zhang Xiang, Xinhua, October 30, 2010 \=]

Xinhua reported: The discovery was made in the Hanyang Mausoleum in the ancient capital of Chang’an, today’s Xi’an City in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province. The monument is the joint tomb of Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C. - A.D. 8) Emperor Jing and his empress. Archaeology at the mausoleum began in the 1980s. Since 1998, researchers from the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology have been excavating the burial pit east of the mausoleum. \=\

“Of the 43 animal fossils discovered in the pit, archaeologists found more than 18 kinds of animals, including three kinds of sea snails and one kind of clam. “The ancient people believed in the afterlife. They thought the dead could possess what they had when they were alive,” said Hu. Many royal tombs were designed and constructed like the imperial palace. The burial pits usually represented different departments of the imperial court, Hu said. “The discovery of animal fossils in this particular pit may shed light on what the emperor ate everyday.” Ge Chengyong, the chief editor of Chinese Culture Relics Press, said, “The seafood may have been tribute offered to the emperor by imperial family relatives living on the Chinese coast. It may also have been businessmen that brought them inland to the capital city.” \=\

“Xi’an is more than one thousand miles away from the Chinese coast, so how could it have arrived in the capital without first spoiling? “During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.), Chinese people used vehicles with refrigeration,” said Ge. “It is thought they may have put ice in the vehicles to preserve perishable cargo.” “The seafood may also have been dried before it was transported,” Ge added. \=\

“Alongside the fossilized seafood shells, fossils of various other kinds of animals — rabbit, fox, leopard, sheep, deer, cat and dog — were also discovered. Hu said, “The cat was kept in the imperial kitchen to catch rats, and so the other animals were all part of the imperial diet.” “Ancient Chinese people valued diversity in their diet. The imperial diet would have include multiple nutrients, multiple flavors and a vast number of dishes.” “Just from the animal fossils discovered so far, we cannot know the whole story of the emperor’s diet. There will be more findings.” \=\

2,000-Year-Old Ice Box Found in North-Central China

In May 2011, archeologists in Shaanxi Province announced they found a primitive “icebox” that dated back at least 2,000 years ago in the ruins of a temporary imperial residence of the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C. – 207 B.C.). The “icebox”, in the shape of a shaft 1.1 meters in diameter and 1.6 meters tall, was unearthed about 3 meters underground in the residence.

Xinhua reported: “The "icebox," unearthed in Qianyang county, contained several clay rings 1.1 meters in diameter and 0.33 meters tall, said Tian Yaqi, a researcher with the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archeology. "The loops were put together to form a shaft about 1.6 meters tall," Tian said. [Source: Xinhua, May 26, 2010 |+|]

“The shaft was unearthed about 3 meters underground within the ruins of an ancient building which experts believed was a temporary imperial residence during the Qin Dynasty (221 - 207 B.C.). "The shaft led to a river valley, but it could not have been a well," said Tian. A well, he explained, would have been much deeper as groundwater could not have been reached only 3 meters underground in arid northwest China. "Nor would it have been possible to build a well inside the house." |+|

“Tian and his colleagues believe the shaft was an ice cellar, known in ancient China as "ling yin," a cool place to store food during the summer. A poem in the "Book of Songs" - a collection of poetry from the Western Zhou Dynasty (11th century -771 B.C.)to the Spring and Autumn Period (770 - 475 B.C.)- says food kept in the "ling yin" will to stay fresh for three days in the summer. "If ice cellars were popular more than 2,000 years ago, it certainly sounds reasonable that the emperor and court officials would have one in their residence," said Tian. Covering an area of about 22,000 square meters, the shaft and the residence were first discovered by villagers building homes in 2006. The area was immediately fenced off by authorities to protect the heritage site.” Research work began in March 2010 and ended in May the same year. |+|

Early History of Tea

tea plants

Originating from Southeast Asia and the Yunnan province of China, tea was mentioned in a Chinese dictionary around A.D. 350. Tea processing is believed to date to around A.D. 500. According to a Chinese myth, tea was discovered about 5,000 years ago by Shennong, a legendary emperor of China who was sipping a bowl of hot water when a sudden gust of wind blew some tea tree twigs into the water.

Tea was brought to imperial China from Southeast Asia about A.D. 900. It became popular during Tang dynasty, when it was associated with Buddhism (monks reportedly used it to stay awake while meditating). During this period of time, tea was not prepared like it is today. The leaves were first steamed and compressed and then dried and pounded in a mortar. China still produces more varieties of tea than any other nation.

The consumption of tea spread from China to Japan and India between around A.D. 1000 or 1100, perhaps by Buddhist monks. It was originally brought over as a medicine not drink. It did not become popular in Japan with the aristocracy until the 17th century and did not really catch on with ordinary people until the 18th century.

World’s Oldest Tea — 2,150 Years Old — Found in Xian Emperor’s Tomb

In January 2016, archaeologists announced they had discovered the oldest tea in the world (2,150 years old) among the treasures buried with a Chinese emperor in Xian and in a tomb in Tibet. Archaeology magazine reported: The finds contain traces of caffeine and theanine — substances particularly characteristic of tea. The tombs are more than 2,000 years old, indicating the beverage was consumed during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220). A Chinese document from 59 B.C. that mentions a drink that might be tea was previously the earliest known record of the beverage. Tea does not grow near the tombs, so the discovery indicates that the Silk Road was a “much more complicated and complex long-distance trade network than was known from written sources,” says researcher Dorian Fuller, an archaeobotany professor at University College London. Tea-producing regions, including remote areas of China and even Myanmar, he adds, had “well established supply lines” feeding into the Silk Road. [Source: Lara Farrar, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

David Keys wrote in The Independent, “New scientific evidence suggests that ancient Chinese liked tea so much that they insisted on being buried with it – so they could enjoy a cup of char in the next world. The new discovery was made by researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and published in Nature’s online open access journal Scientific Reports. “Previously, no tea of that antiquity had ever been found – although a single ancient Chinese text from a hundred years later claimed that China was by then exporting tea leaves to Tibet. By examining tiny crystals trapped between hairs on the surface of the leaves and by using mass spectrometry, they were able to work out that the leaves, buried with a mid second century B.C. Chinese emperor, were actually tea. The scientific analysis of the food and other offerings in the Emperor’s tomb complex have also revealed that, as well as tea, he was determined to take millet, rice and chenopod with him to the next life. [Source: David Keys, The Independent, January 10, 2016 -]

“The tea aficionado ruler – the Han Dynasty Emperor Jing Di – died in 141 B.C., so the tea dates from around that year. Buried in a wooden box, it was among a huge number of items interred in a series of pits around the Emperor’s tomb complex for his use in the next world. Other items included weapons, pottery figurines, an ‘army’ of ceramic animals and several real full size chariots complete with their horses. -

“The tomb, located near the Emperor Jing Di’s capital Chang’an (modern Xian), can now be visited. Although the site was excavated back in the 1990s, it is only now that scientific examination of the organic finds has identified the tea leaves. The tea-drinking emperor himself was an important figure in early Chinese history. Often buffeted by intrigue and treachery, he was nevertheless an unusually enlightened and liberal ruler. He was determined to give his people a better standard of living and therefore massively reduced their tax burden. He also ordered that criminals should be treated more humanely – and that sentences should be reduced. What’s more, he successfully reduced the power of the aristocracy. -

“The tea discovered in the Emperor’s tomb seems to have been of the finest quality, consisting solely of tea buds – the small unopened leaves of the tea plant, usually considered to be of superior quality to ordinary tea leaves. “The discovery shows how modern science can reveal important previously unknown details about ancient Chinese culture. The identification of the tea found in the emperor’s tomb complex gives us a rare glimpse into very ancient traditions which shed light on the origins of one of the world’s favourite beverages,” said Professor Dorian Fuller, Director of the International Centre for Chinese Heritage and Archaeology, based in UCL, London.” -

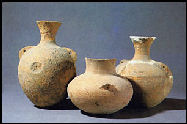

World’s Oldest Wine from China?

Vessels with the

oldest wine The earliest evidence of wine making comes from China: traces of a fermented drink made with rice, honey, and either grapes or hawthorne fruit found in Jiahu and dated to 7000 B.C. The previous earliest evidence of wine making comes from artifacts dated to 5400 B.C. from Firuz Tepe in Iran. Analysis by University of Pennsylvania's Museum of Archeology and Anthropology of the pores of 9000-year-old pottery shards jars unearthed in Jiahu turned up traces of beeswax, a biomarker for honey; tartaric acid, a biomaker for grapes, wine and Chinese hawthorne fruit; and other traces that ‘strongly suggested” rice.

There is some debate whether the concoction was a wine or a beer or something else. Grapes were not introduced to China from Central Asia until many millennia after 7000 B.C., so it is reasoned the tartaric acid likely comes from hawthorne fruit which is ideal for making wine because it has a high sugar content and can harbor the yeast for fermentation. Wine traces has also been found in a pottery sample from a Chinese tomb dated to 5000 B.C.

Nadia Durrani wrote in World Archaeology: “Jiahu, in the Yellow River Basin of the Henan province of northern China, is a compelling archaeological site, renowned for its cultural and artistic relics. Among the ancient houses, archaeologists have uncovered kilns, turquoise carvings, stone tools and flutes made from bone...Until this discovery, the oldest evidence of fermented beverages was dated to 5400 B.C., and comes from the Neolithic site of Hajji Firuz Tepe in Iran. Perhaps, suggests Dr Patrick McGovern a molecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania who undertook the new research, the innovation happened at the same time in both countries, but that older evidence from Iran remains to be found. Were there some indirect ties between the Middle east and Central Asia at that time in ancient civilization, McGovern wonders. [Source: Nadia Durrani, World Archaeology, January 6, 2005]

McGovern recreated the 9,000-year-old concoction from rice, honey and hawthorn, calling it Chateau Jiahu, and had it commercially produced and sold at some places in the U.S. and Canada. Debra Black wrote in TheStar.com: McGovern and the folks at Dogfish Head Craft Brewery in Milton, Delaware decided to take the ancient beer’s ingredients and make a modern-day version of it. No easy task for the modern beer maker. “All that Patrick McGovern could tell us is what the evidence was or a laundry list of organic substances,” said Sam Calagione, founder and president of the brewery. “From there we have to create a recipe. We have to come up with the percentage or ratios and volumes of weight of honey, rice and fruit. We have to figure out how strong an alcohol it might have been. Whether it was filtered or cloudy, carbonated or flat. We have a lot of creative latitude to bring a modern interpretation of this ancient beverage back to life.” And it seems the company has succeeded with Chateau Jiahu winning a gold medal at the Great American Beer Fest in 2009. [Source: Debra Black TheStar.com, June 2, 2010]

Other Ancient Wine’s from China?

Nadia Durrani wrote in World Archaeology: “The local liking for liquor continued down the centuries, according to McGovern’s research. He also analysed samples of 3,000-year-old wine from hermetically sealed bronze vessels found in Shang Dynasty burial tombs from the Yellow River Basin. Here, wine was deposited in the tombs of high-ranking individuals to sustain them in the afterlife. [Source: Nadia Durrani, World Archaeology, January 6, 2005 ++]

brick showing wine making in ancient China

“The wine, which was clear and colourless, had been preserved because a thin layer of rust had sealed the bronze jars completely. When opened, it was initially floral scented, but after exposure to the atmosphere the aroma quickly degraded and gave off a scent akin to nail-polish remover. Analysis later revealed that the wine was flavoured with herbs and flowers or tree resins. One of the ancient jars also contained a liquid that had traces of wormwood, suggesting the beverage might have been an early version of absinthe.” ++

According to China.org: “Artifacts produced during the Shang Dynasty consisted mainly of wine vessels. It shows the important role wine drinking played in the lives of Shang people. According to historical documents, the best wine at the time was made with millet. Historians argued that the imperial class was so fond of a drop it led to the collapse of the Shang Dynasty. Rulers of the Western Zhou Dynasty learned from Shang people and restricted drinking.” [Source: China.org, March 13, 2003, This article first appeared in 2003's third issue of Collections, a Chinese language monthly magazine ~]

In May, 2011, Chinese scientists announced they had found 2000-year-old wine in Henan province. Wang Hanlu wrote in the People's Daily, “A Western Han dynasty ancient tomb group was accidentally found at a construction site in Puyang city, China’s Henan province, on April 10. After a period of protective excavation of the tomb group, archaeologists found more than 230 ancient tombs in all, and a total of more than 600 cultural relics have been unearthed so far. During the excavation, archaeologists discovered an airtight copper pot covered in rust. They found the pot had a liquid weighing about half a kilogram in it. On May 10, the Beijing Mass Spectrum Center, which is a joint accrediting body based on the Chinese Academy of Science, identified the liquid in the ancient pot as wine. [Source: Wang Hanlu, People's Daily Online, May 11, 2011]

Chinese ritual vessels

Beer Brewed in China 5000 Years Ago

In May 2016, archaeologists announced they had discover evidence of a 5,000-year-old beer concoction and the earliest known occurrence of barley in China at Mijiaya, a Yangshao archaeological site in China's Shaanxi province. The researchers found yellowish remnants in wide-mouthed pots, funnels and amphorae excavated from the site that suggested the vessels were used for beer brewing, filtration and storage.

According to Live Science: Stoves found nearby were probably used to provide heat for mashing the grains, according to the archaeologists. The beer recipe used a variety of starchy grains, including barley, as well as tubers, which would have added starch for the fermentation process and sweetness to the flavor of the beer, the researchers said. The prehistoric brewery at the Mijiaya site consisted of ceramic pots, funnels and stoves found in pits that date back to the Neolithic (late Stone Age) Yangshao period, around 3400 to 2900 B.C., said Jiajing Wang, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University in California and lead author the paper on the research, published in May 23, 2016 edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 23, 2016 +]

Popular Archaeology reported: “Archaeological artifacts from a site in northern China suggest a 5,000-year-old recipe for beer, according to a study. The time of onset of beer brewing in ancient China remains unclear. Jiajing Wang and colleagues report the discovery of brewing artifacts in two pits dated to around 3400-2900 B.C. and unearthed at Mijiaya, an archaeological site near a tributary of the Wei River in northern China. [Source: popular-archaeology.com, *“Revealing a 5000-year-old beer recipe in China,” by Jiajing Wang et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 23, 2016 ^|^]

“Yellowish remnants found in wide-mouthed pots, funnels, and amphorae suggest that the vessels were used for beer brewing, filtration, and storage. Stoves found in the pits likely provided heat for mashing grains. Morphological analysis of starch grains and phytoliths found inside the artifacts revealed broomcorn millets, barley, Job’s tears, and tubers; some starch grains bore marks reminiscent of malting and mashing. The presence of oxalate, a byproduct of beer brewing that was identified using ion chromatography, in some of the artifacts further supported their use as brewing vessels. ^|^

“Together, the lines of evidence suggest that the Yangshao people may have concocted a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that ushered the cultural practice of beer brewing into ancient China. According to the authors, the identification of barley residues in the Mijiaya artifacts represents the earliest known occurrence of barley in China, pushing back the crop’s advent in the country by approximately 1,000 years and suggesting that the crop may have been used as a beer-making ingredient long before it became an agricultural staple.” ^|^

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: “The researchers said it is unclear when beer brewing began in China, but the residues from the 5,000-year-old Mijiaya artifacts represent the earliest known use of barley in the region by about 1,000 years. They also suggest that barley was used to make beer in China long before the cereal grain became a staple food there, the researchers noted...Wang said that some Chinese scholars had suggested several years ago that the Yangshao funnels might have been used to make alcohol, but there had been no direct evidence until now. In the summer of 2015, the Stanford researchers traveled to Xi'an and visited the Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology, where the artifacts from the Mijiaya site are now stored. The scientists extracted residues from the artifacts, and their analysis of the residues turned out to prove their hypothesis: that "people in China brewed beer with barley around 5,000 years ago," Wang said. +\

“The Mijiaya site was discovered in 1923 by Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, Wang said. The site, located near the present-day center of the city of Xi'an, was excavated by Chinese archaeologists between 2004 and 2006, before being developed for modern residential buildings. After the full excavation report was published in 2012, Wang's co-author on the new paper, archaeologist Li Liu of Stanford, noticed that the pottery assemblages from two of the pits could have been used to make alcohol, mainly because of the presence of funnels and stoves.” +\

Barley: a Surprise Ingredient in China’s 5,000-Year-Old Beer

Barley fruit Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: “Barley might have been the "secret ingredient" in a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that has been reconstructed from residues on prehistoric pots from China, according to new archaeological research. Scientists conducted tests on ancient pottery jars and funnels found at the Mijiaya archaeological site in China's Shaanxi province. The analyses revealed traces of oxalate — a beer-making byproduct that forms a scale called "beerstone" in brewing equipment — as well as residues from a variety of ancient grains and plants. These grains included broomcorn millets, an Asian wild grain known as "Job's tears," tubers from plant roots, and barley. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 23, 2016 +]

“Barley is used to make beer because it has high levels of amylase enzymes that promote the conversion of starches into sugars during the fermenting process. It was first cultivated in western Asia and might have been used to make beer in ancient Sumer and Babylonia more than 8,000 years ago, according to historians. Wang told Live Science that the discovery of barley in such early artifacts was a surprise to the researchers. +\

“Barley was the main ingredient for beer brewing in other parts of the world, such as in ancient Egypt, she said, and the barley plant might have spread into China along with the knowledge of its special use in making beer. "It is possible that when barley was introduced from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China, it came with the knowledge that the grain was a good ingredient for beer brewing," Wang said. "So it was not only the introduction of a new crop, but also the knowledge associated with the crop." +\

“Wang and her co-authors wrote that barley had been found in a few Bronze Age sites in the Central Plain of China, all dated to around or after 2000 B.C. However, barley did not become a staple crop in the region until the Han dynasty, from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, the researchers said. "Together, the lines of evidence suggest that the Yangshao people may have concocted a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that ushered the cultural practice of beer brewing into ancient China," the archaeologists wrote in the paper. "It is possible that the few rare finds of barley in the Central Plain during the Bronze Age indicate their earlier introduction as rare, exotic food."

The researchers wrote: "Our findings imply that early beer making may have motivated the initial translocation of barley from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China before the crop became a part of agricultural subsistence in the region 3,000 years later." It's even possible that beer-making technology aided the development of complex human societies in the region, the researchers said. "Like other alcoholic beverages, beer is one of the most widely used and versatile drugs in the world, and it has been used for negotiating different kinds of social relationships," the archaeologists wrote. "The production and consumption of Yangshao beer may have contributed to the emergence of hierarchical societies in the Central Plain, the region known as 'the cradle of Chinese civilization,'" they added. +\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021