YANGSHAO CULTURE

Banshan painted pottery

The Yangshao culture was a Neolithic culture that thrived on the Loess Plateau along the Yellow River in China. In existence from around 5000 B.C. to 3000 B.C., it is named after Yangshao, the first excavated representative village of this culture, which was discovered in 1921 in Henan Province by the Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960). The culture flourished mainly in the provinces of Henan, Shaanxi and Shanxi. Major sites includes Banpo and Jiangzhai. The Yangshao culture was preceded by the Peiligang culture (Jiahu, see separate articles), Dadiwan culture and Cishan culture. It was followed by the Longshan culture. A culture related to the Yangshao culture that emerged in the northwest is classified into three categories, the Banshan, Majiayao, and Machang, each categorized by the types of pottery produced.[Sources: Wikipedia, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

The Yangshao archaeological culture is well known for its painted pottery. It consisted of hundreds of settlements along the Yellow River and Wei River regions, and stretched across the northwestern plains from Shaanxi province in central China to Gansu province in the west. Yangshao village, the source of the Yangshao name, is located near the confluence of the Yellow, Fen and Wei rivers. Around 4000 B.C, about 800 years before civilizations developed in Mesopotamia and Egypt, carefully laid-out villages were founded by hunter-farmers on the Yellow and Wei rivers.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The Yangshao culture is one of the two great Neolithic cultures that proliferated in northern China. Its earliest sites in the Wei River valley date from about 5000 B.C., and the westernmost regions of the Yangshao culture seem to persist until approximately 2000 B.C. In other words, Yangshao culture possessed a history of three thousand years – as long as the time from the Zhou conquest of the Shang to the election of George W. Bush. Yet because Yangshao society was pre-literate, we are unable to know it in any narrative form that would convey the enduring stream of social and political drama and surely make it seem one of the great civilizations of world history...We see in Yangshao culture a likely ancestor of the elaborate kinship structures of later Chinese society and their associated ritual aesthetic.We cannot, however, identify the Yangshao people as the forbears of the warrior society of walled China. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University ]

Yanhshao is a broad term. There are many Yangshao sites. Some scholars also group Neolithic culture sites into two broad cultural complexes: the Yangshao cultures in central and western China, and the Longshan cultures in eastern and southeastern China. The Yangshao culture (5000-3000 B.C.)of the middle Yellow River valley, known for its painted pottery, and the later Longshan culture (2500-2000 B.C.)of the east, distinguished for its black pottery, are te best known of the ancient Chinese Yellow River cultures. Traditionally it was believed that Chinese civilization arose in the Yellow River valley and spread out from this center. Recent archaeological discoveries, however, reveal a far more complex picture of Neolithic China, with a number of distinct and independent cultures in various regions interacting with and influencing each other. Other major Neolithic cultures were the Hongshan culture in northeastern China, the Liangzhu culture in the lower Yangzi River delta, the Shijiahe culture in the middle Yangzi River basin and primitive settlements and burial grounds found at Liuwan in Qinghai Province, Wangyin in Shandong Province, Xinglongwa in Inner Mongolia, and the Yuchisi in Anhui Province, among many others. [Source: University of Washington]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PREHISTORIC AND SHANG-ERA CHINA factsanddetails.com; FIRST CROPS AND EARLY AGRICULTURE AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; WORLD'S OLDEST RICE AND EARLY RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT FOOD, DRINK AND CANNABIS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINA: THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WRITING? factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC CHINA factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000-5700 B.C.): CHINA’S EARLIEST CULTURE AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com; JIAHU (7000 B.C. to 5700 B.C.): HOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST WINE AND SOME OF THE WORLD’S OLDEST FLUTES, WRITING, POTTERY AND ANIMAL SACRIFICES factsanddetails.com; HONGSHAN CULTURE AND OTHER NEOLITHIC CULTURES IN NORTHEAST CHINA factsanddetails.com; LONGSHAN AND DAWENKOU: THE MAIN NEOLTHIC CULTURES OF EASTERN CHINA factsanddetails.com; ERLITOU CULTURE (1900–1350 B.C.): CAPITAL OF THE XIA DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; KUAHUQIAO AND SHANGSHAN: THE OLDEST LOWER YANGTZE CULTURES AND THE SOURCE OF THE WORLD’S FIRST DOMESTICATED RICE factsanddetails.com; HEMUDU, LIANGZHU AND MAJIABANG: CHINA’S LOWER YANGTZE NEOLITHIC CULTURES factsanddetails.com; EARLY CHINESE JADE CIVILIZATIONS factsanddetails.com; NEOLITHIC TIBET, YUNNAN AND MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Chinese Neolithic: Trajectories to Early States” (New Studies in Archaeology) by Li Liu Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “New Perspectives on China’s Past: Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century,” edited by Xiaoneng Yang Amazon.com; “The Origins of Chinese Civilization" edited by David N. Keightley Amazon.com; “Liangzhu Culture” by Bin Liu, Ling Qin, et al. Amazon.com; “Hongshan Jade: The oldest, most imaginative jades full of mysterious beauty” Kako Crisci Amazon.com ; “Qijia (Jades of the Qijia and related northwestern cultures of early China, ca. 2100-1600 BCE” by Dr. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson and Gu Fang Amazon.com ; “The Story of Rice” by Xiaorong Zhang Amazon.com

Yangshao Archeology

According to the Princeton University Art Museum: “Yangshao culture in central China can be divided into two main phases: Banpo (ca. 4800–ca. 4300 B.C.) and Miaodigou (ca. 4000–ca. 3500 B.C.). The archaeological site at Banpo was located just east of modern-day Xi’an in Shaanxi province. Banpo was discovered in 1953 and excavated between 1954 to 1957. Little is known about the daily lives of the people at Banpo, but excavations have uncovered a settlement covering around 50,000 square feet that included dwelling areas, subterranean storage pits, pens for holding livestock, several pottery kilns, and cemetery areas. The settlement was also located above a stream that provided a reliable water source, and terraces were built to prevent flooding. The Miaodigou phase is named after a site in northwestern Henan province. The type of ceramic produced in this phase was commonly decorated with painted black lines, dots, leaf-like shapes, and roundels. This decorative vocabulary appears to be the basis for designs on later Miajiayao culture pottery. [Source: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004 etcweb.princeton.edu ]

Xinwei Li wrote in “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology,”: “The excavation conducted by the famous Swedish archaeologist and geologist John Andersson at the Yangshao site, Mianchi, Henan province in 1921 (Andersson 1923) was regarded as marking the emergence of modern archaeology in China (Chen 1997). Although the remains found by Andersson led to the name “Yangshao culture” or “the Painted Pottery culture” soon after the excavation, the painted pottery unearthed from the site in fact mainly belongs to the middle period of the Yangshao culture. Li Ji, father of Chinese archaeology, launched the first excavation directed by a Chinese archaeologist at the Xiyincun site in Xiaxian, Shanxi in 1926 and found the same painted pottery (Li Ji 2006). However, the excavations at the Miaodigou site in Shaanxian, Henan, from 1956 to 1957 directed by An Zhimin, then a young archaeologist from the newly established Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, provide the first clear picture of the middle Yangshao period in the central Yellow river valley. The monograph on the excavations published in 1959 – the first archaeological report of the People's Republic of China (IA, CASS 1959) – gives the middle Yangshao remains a new name – “the Miaodigou Type.”Some nostalgic archaeologists like to use the name “Xiyincun culture” to refer to the same remains (Zhang Zhongpei 1996), but Miaodigou Type or Miaodigou is still the most common name.” [Source: Xinwei Li, CHAPTER 11. “The Later Neolithic Period in the Central Yellow River Valley Area, c.4000–3000 B.C..” “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology,” Edited by Anne P. Underhill, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013 ~|~]

The Yangshao culture is conventionally divided into three phases: 1) The early period (or Banpo phase, c. 5000–4000 B.C.)is represented by the Banpo, Jiangzhai, Beishouling and Dadiwan sites in the Wei River valley in Shaanxi. 2) The middle period (or Miaodigou phase, c. 4000–3500 B.C.)saw an expansion of the culture in all directions, and the development of hierarchies of settlements in some areas, such as western Henan. 3) The late period (c. 3500–3000 B.C.)saw a greater spread of settlement hierarchies. The first wall of rammed earth in China was built around the settlement of Xishan (25 hectares) in central Henan (near modern Zhengzhou). The Majiayao culture (c. 3300–2000 B.C.)to the west is now considered a separate culture that developed from the middle Yangshao culture through an intermediate Shilingxia phase.

Yangshao Culture Life and Agriculture

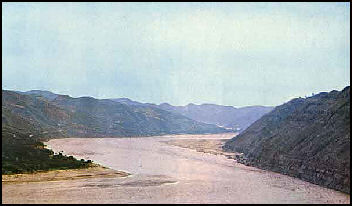

Yellow River, home of some

of the world's earliest civilizations By 4000 B.C. the Yangshao domesticated dogs, pigs and perhaps cattle and horses. Based on studies of amounts and types of carbon and nitrogen detected in bones found in graves, archeologists have determined that farmers, pigs and dogs that lived in the Yellow River Valley between 4,000 and 7,000 years ago ate lots of millet because it is the region's only C4 food. C4 is a carbon isotope associated with a certain kind of photosynthesis that is found in only some plants. Among some animals millet made up as much as 90 percent of their diet.

Yangshao Culture villagers hunted, fished, gathered and practiced primitive agriculture. Stone tools unearthed by archaeologists included fishing net sinkers, knives, shovels, millstones and arrowheads. Fishermen used nets and needles, harpoons and hooks made from bone. Craftsmen made tools from stone and jewelry from shells and animal teeth. Pottery was decorated with geometric figures, pictures of running deer and markings that could possible have been a primitive form of writing. Their water flasks are collected today as works of art.

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The economy of the Yangshao culture was largely agricultural, and, like the Peiligang culture, millet was the dominant crop. But we also see evidence of other forms of distinctly Chinese types of agriculture, such as the cultivation of hemp for cloth fiber and the earliest evidence of sericulture: the nurturing of silkworms. Yangshao sites indicate a broader range of animal husbandry, including dogs and pigs, sheep, goats, and cattle. Hunting yielded a wide variety of meats: badger, raccoon, fox, bear, deer, turtles, and the occasional leopard or rhinoceros. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

In some sites using foxtail millet is the main crop; in others broom-corn millet, though some evidence of rice has been found. The exact nature of Yangshao agriculture, small-scale slash-and-burn cultivation versus intensive agriculture in permanent fields, is currently a matter of debate. Once exhausting the soil, residents picked up their belongings, move to new lands, and construct new villages. However, Middle Yangshao settlements such as Jiangzhi contain raised-floor buildings that may have been used for the storage of surplus grains. Grinding stones for making flour were also found. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Yangshao people kept pigs and dogs. Sheep, goats, and cattle are found much more rarely. Much of their meat came from hunting and fishing. Their stone tools were polished and highly specialized. They may also have practiced an early form of silkworm cultivation. The Yangshao culture produced silk to a small degree and wove hemp. Men wore loin cloths and tied their hair in a top knot. Women wrapped a length of cloth around themselves and tied their hair in a bun. +

Beer Brewed in the Yangshao Area 5000 Years Ago

In May 2016, archaeologists announced they had discover evidence of a 5,000-year-old beer concoction and the earliest known occurrence of barley in China at Mijiaya, a Yangshao archaeological site in China's Shaanxi province. The researchers found yellowish remnants in wide-mouthed pots, funnels and amphorae excavated from the site that suggested the vessels were used for beer brewing, filtration and storage.

According to Live Science: Stoves found nearby were probably used to provide heat for mashing the grains, according to the archaeologists. The beer recipe used a variety of starchy grains, including barley, as well as tubers, which would have added starch for the fermentation process and sweetness to the flavor of the beer, the researchers said. The prehistoric brewery at the Mijiaya site consisted of ceramic pots, funnels and stoves found in pits that date back to the Neolithic (late Stone Age) Yangshao period, around 3400 to 2900 B.C., said Jiajing Wang, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University in California and lead author the paper on the research, published in May 23, 2016 edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 23, 2016 +]

Popular Archaeology reported: “Archaeological artifacts from a site in northern China suggest a 5,000-year-old recipe for beer, according to a study. The time of onset of beer brewing in ancient China remains unclear. Jiajing Wang and colleagues report the discovery of brewing artifacts in two pits dated to around 3400-2900 B.C. and unearthed at Mijiaya, an archaeological site near a tributary of the Wei River in northern China. [Source: popular-archaeology.com, *“Revealing a 5000-year-old beer recipe in China,” by Jiajing Wang et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, May 23, 2016 ^|^]

“Yellowish remnants found in wide-mouthed pots, funnels, and amphorae suggest that the vessels were used for beer brewing, filtration, and storage. Stoves found in the pits likely provided heat for mashing grains. Morphological analysis of starch grains and phytoliths found inside the artifacts revealed broomcorn millets, barley, Job’s tears, and tubers; some starch grains bore marks reminiscent of malting and mashing. The presence of oxalate, a byproduct of beer brewing that was identified using ion chromatography, in some of the artifacts further supported their use as brewing vessels. ^|^

“Together, the lines of evidence suggest that the Yangshao people may have concocted a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that ushered the cultural practice of beer brewing into ancient China. According to the authors, the identification of barley residues in the Mijiaya artifacts represents the earliest known occurrence of barley in China, pushing back the crop’s advent in the country by approximately 1,000 years and suggesting that the crop may have been used as a beer-making ingredient long before it became an agricultural staple.” ^|^

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: “The researchers said it is unclear when beer brewing began in China, but the residues from the 5,000-year-old Mijiaya artifacts represent the earliest known use of barley in the region by about 1,000 years. They also suggest that barley was used to make beer in China long before the cereal grain became a staple food there, the researchers noted...Wang said that some Chinese scholars had suggested several years ago that the Yangshao funnels might have been used to make alcohol, but there had been no direct evidence until now. In the summer of 2015, the Stanford researchers traveled to Xi'an and visited the Shaanxi Institute of Archaeology, where the artifacts from the Mijiaya site are now stored. The scientists extracted residues from the artifacts, and their analysis of the residues turned out to prove their hypothesis: that "people in China brewed beer with barley around 5,000 years ago," Wang said. +\

“The Mijiaya site was discovered in 1923 by Swedish archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, Wang said. The site, located near the present-day center of the city of Xi'an, was excavated by Chinese archaeologists between 2004 and 2006, before being developed for modern residential buildings. After the full excavation report was published in 2012, Wang's co-author on the new paper, archaeologist Li Liu of Stanford, noticed that the pottery assemblages from two of the pits could have been used to make alcohol, mainly because of the presence of funnels and stoves.” +\

Barley: a Surprise Ingredient in China’s 5,000-Year-Old Beer

Barley fruit Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: “Barley might have been the "secret ingredient" in a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that has been reconstructed from residues on prehistoric pots from China, according to new archaeological research. Scientists conducted tests on ancient pottery jars and funnels found at the Mijiaya archaeological site in China's Shaanxi province. The analyses revealed traces of oxalate — a beer-making byproduct that forms a scale called "beerstone" in brewing equipment — as well as residues from a variety of ancient grains and plants. These grains included broomcorn millets, an Asian wild grain known as "Job's tears," tubers from plant roots, and barley. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, May 23, 2016 +]

“Barley is used to make beer because it has high levels of amylase enzymes that promote the conversion of starches into sugars during the fermenting process. It was first cultivated in western Asia and might have been used to make beer in ancient Sumer and Babylonia more than 8,000 years ago, according to historians. Wang told Live Science that the discovery of barley in such early artifacts was a surprise to the researchers. +\

“Barley was the main ingredient for beer brewing in other parts of the world, such as in ancient Egypt, she said, and the barley plant might have spread into China along with the knowledge of its special use in making beer. "It is possible that when barley was introduced from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China, it came with the knowledge that the grain was a good ingredient for beer brewing," Wang said. "So it was not only the introduction of a new crop, but also the knowledge associated with the crop." +\

“Wang and her co-authors wrote that barley had been found in a few Bronze Age sites in the Central Plain of China, all dated to around or after 2000 B.C. However, barley did not become a staple crop in the region until the Han dynasty, from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, the researchers said. "Together, the lines of evidence suggest that the Yangshao people may have concocted a 5,000-year-old beer recipe that ushered the cultural practice of beer brewing into ancient China," the archaeologists wrote in the paper. "It is possible that the few rare finds of barley in the Central Plain during the Bronze Age indicate their earlier introduction as rare, exotic food."

The researchers wrote: "Our findings imply that early beer making may have motivated the initial translocation of barley from western Eurasia into the Central Plain of China before the crop became a part of agricultural subsistence in the region 3,000 years later." It's even possible that beer-making technology aided the development of complex human societies in the region, the researchers said. "Like other alcoholic beverages, beer is one of the most widely used and versatile drugs in the world, and it has been used for negotiating different kinds of social relationships," the archaeologists wrote. "The production and consumption of Yangshao beer may have contributed to the emergence of hierarchical societies in the Central Plain, the region known as 'the cradle of Chinese civilization,'" they added. +\

Millet First Domesticated in Yangshao Area 10,000 Years Ago

millet

The world’s oldest millet was found in the Yangshao area although it proceeded the Yangshao culture by about 5,000 years. Research analysis in “Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago” concluded that “the earliest significant common millet cultivation system was established in the semiarid regions of China by 10,000 cal yr BP, and that the relatively dry condition in the early Holocene may have been favorable for the domestication of common millet over foxtail millet. Our study shows that common millet appeared as a staple crop in northern China ̃10,000 years ago, suggesting that common millet might have been domesticated independently in this area and later spread to Russia, India, the Middle East, and Europe. Nevertheless, like Mesopotamia, where the spread of wheat and barley to the fertile floodplains of the Lower Tigris and Euphrates was a key factor in the emergence of civilization, the spread of common millet to the more productive regions of the Yellow River and its tributaries provided the essential food surplus that later permitted the development of social complexity in the Chinese civilization.” [Source: “Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago” by Houyuan Lua, Jianping Zhanga, Kam-biu Liub, Naiqin Wua, Yumei Lic, Kunshu Zhoua, Maolin Yed, Tianyu Zhange, Haijiang Zhange, Xiaoyan Yangf, Licheng Shene, Deke Xua and Quan Lia. Edited by Dolores R. Piperno, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and National Museum of Natural History, Washington, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 17, 2009 ++]

The above study reported “the discovery of husk phytoliths and biomolecular components identifiable solely as common millet from newly excavated storage pits at the Neolithic Cishan site, China, dated to between ca. 10,300 and ca. 8,700 calibrated years before present (cal yr BP). After ca. 8,700 cal yr BP, the grain crops began to contain a small quantity of foxtail millet. Our research reveals that the common millet was the earliest dry farming crop in East Asia, which is probably attributed to its excellent resistance to drought.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapn.wordpress.com ++]

“Foxtail millet (Setaria italica) and common millet (or broomcorn millet; Panicum miliaceum) were among the world’s most important and ancient domesticated crops. They were staple foods in the semiarid regions of East Asia (China, Japan, Russia, India, and Korea) and even in the entire Eurasian continent before the popularity of rice and wheat, and are still important foods in these regions today.” ++

Cishan in Northern China: Home of the World’s Oldest Millet

According to the paper “Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago”: “Thirty years ago, the world’s oldest millet remains, dating to ca. 8,200 calibrated years before present (cal yr BP), were discovered at the Early Neolithic site of Cishan, northern China. The site contained more than 50,000 kilograms of grain crops stored in the storage pits. Until now, the importance of these findings has been constrained by limited taxonomic identification with regard to whether they are from foxtail millet (S. italica) or common millet (P. miliaceum), because the early reported S. italica identifications are not all accepted. This article presents the phytoliths, biomolecular records, and new radiocarbon dating from newly excavated grain crop storage pits at the Cishan site. Large modern reference collections are used to compare and contrast microfossil morphology and biomolecular components in different millets and related grass species. The renewed investigations show that common millet agriculture arose independently in the semiarid regions of China by 10,000 cal yr BP. [Source: “Earliest domestication of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) in East Asia extended to 10,000 years ago” by Houyuan Lua, Jianping Zhanga, Kam-biu Liub, Naiqin Wua, Yumei Lic, Kunshu Zhoua, Maolin Yed, Tianyu Zhange, Haijiang Zhange, Xiaoyan Yangf, Licheng Shene, Deke Xua and Quan Lia. Edited by Dolores R. Piperno, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and National Museum of Natural History, Washington, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 17, 2009 ++]

The Cishan site (36̊34.511' N, 114̊06.720' E) is located near the junction between the Loess Plateau and the North China Plain at an elevation of 260–270 meters above sea level. The archaeological site, containing a total of 88 storage pits with significant quantities (about 109 cubic meters) of grain crop remains, was excavated from 1976 to 1978. Each storage pit included 0.3- to 2-meter-thick grain crops, which were well preserved and found in situ in the 3- to 5-meter-deep loess layer. All grain remains have been oxidized to ashes soon after they were exposed to air. Archaeological excavations also revealed the remains of houses and numerous millstones, stone shovels, grind rollers, potteries, rich faunal remains, and plant assemblages including charred fruits of walnut (Juglans regia), hazel (Corylus heterophylla), and hackberry (Celtis bungeana). Only 2 14C dates of charcoal from previously excavated H145 and H48 storage pits yielded uncalibrated ages of 7355 ± 100 yr BP and 7235 ± 105 yr BP, respectively. These remains represent the earliest evidence for the significant use of dry-farming crop plants in the human diet in East Asia. They also suggest that by this time agriculture had already been relatively well developed here. ++

depiction of a Banpo village

Yangshou Villages

Yangshao villages typically covered ten to fourteen acres and were composed of houses around a central square. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Yangshao villages were composed of groups of houses, square, oblong, and round. A single village could possess several such groups, which were generally organized around a central area. Houses typically were a single room with about 150 square feet of floor space, about the size of a contemporary American family room. Floors were on ground level or slightly below, walls were of clay and straw, and roofs were probably thatched and supported by wooden posts, sometimes latticed with rafters. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“At the center of the village, there was sometimes a “longhouse,” a lodge-like dwelling or ceremonial center up to sixty feet long, with rooms and multiple hearths. The entire village was often surrounded by a ditch which separated the village from the area in which the dead were buried. The organization of the village into distinct areas of multiple dwellings of various shapes and sizes suggests that members of a single village were grouped by lineage relationships, rather than considering themselves an undifferentiated unit.We will see that this idea is suggested also in burial practices. /+/

“What is very much absent from the widely dispersed Yangshao sites is one of the most distinctive features of later Chinese culture: walled settlements. The Yangshao were clearly not a wall-building culture. In later China, wall-building was an activity of agriculturalists. Walls allowed the sedentary farming population a secure retreat in the event of attack from nomads or other more mobile tribes, and provided defensible bases for agricultural communities to war against one another as well. The Yangshao people were apparently unwarlike: very few of the many tools excavated at the village sites would have been suitable as weapons of war. /+/

Yangshou Houses and Household Items

Yangshao houses were built by digging a rounded rectangular pit a few feet deep. Then they were rammed, and a lattice of wattle was woven over it. Then it was plastered with mud. The floor was also rammed down. Next, a few short wattle poles would be placed around the top of the pit, and more wattle would be woven to it. It was plastered with mud, and a framework of poles would be placed to make a cone shape for the roof. Poles would be added to support the roof. It was then thatched with millet stalks. There was little furniture; a shallow fireplace in the middle with a stool, a bench along the wall, and a bed of cloth. Food and items were placed or hung against the walls. A pen would be built outside for animals. [Source: Wikipedia]

In a 2005 article entitled “big Yangshao house discovered at the Shuibei site, Binxian, Shaanxi”, Chinese Archaeology reported: “The 12 hectare large Shuibei site is located at the bank of the Jing River to the south of the Shuibei Village, Tandian Township, Binxian County, Shaanxi Province. An excavation conducted by the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics from June to November this year exposed an area nearly 2400 square meters m and unearthed 107 pits, 4 houses, 1 kiln, 3 burials as well as a large number of pottery, stone tools and bone tools. [Source: Chinese Archaeology, December 14, 2005 ==]

Banpo storage pits and drainage ditches

“The big house, which is the largest Yangshao house ever found in Shaanxi, is 20.1 meters from east to west, 12.2 meters from south to north and 190 square meters in size. Its floor consists of several layers including a burnt hard black layer below and a level cement-like surface made of lime concretions and sand. The kiln has a round fire pit and a round pottery chamber with two surrounding fire channels. ==

“Majority of ceramic vessels from the site were made of red fine clay or sandy clay. Some are gray, brown or orange in colors. Common surface decorations include the thread pattern, the cord pattern, the string pattern, the attached slip and the basket pattern. Painted designs of dots, arcs and connected hooks were found on many vessels. Main vessel types include the rail-like-rim pot, the double-rims, the level rim or the trump-like mouth pointed-bottom vase, the curved-rim basin with color painting, the bo bowl, the contracted urn, the big-mouth double-rims jar, the round-belly pot, the wide-rim shallow or deep basin, the shallow level bottom bo bowl, the thick-rim jar and the large-mouth deep belly pot. There are also some ceramic knives, spindle-wheels, rings, spades and lids. Most of the stone tools, including knives, pestles, axes, chisels, balls and whetstones, are polished. Bones were used to made awls, needles, arrowheads and hairpins. ==

“The majority of the Shuibei assemblage can be dated to the middle and late Yangshao period (about cal. 4000 to cal. 5000 B.C.). However, remains as early as the Laoguantai period and as late as the Longshan period were also recognized. As the first central prehistoric site ever been excavated in large scale in the upper and lower Jing River valley, the site is of great value to the study of chronology of prehistoric cultures and changes of settlement patterns in this area.” ==

Yangshou Pottery

pottery basin

Some of the earliest examples of clay pottery found in China are clay vessels — some of them with painted flowers, fish, human faces, animals, vaginas and geometric designs—created as far back as 6000 B.C. in the Yangshao area. Yangshao artisans created fine white, red, and black painted pottery. Unlike the later Longshan culture, the Yangshao culture did not use pottery wheels in pottery-making. Excavations found that children were buried in painted pottery jars.

Dr. Eno of Indiana University wrote: “One of the most distinctive features of Yangshao culture is its beautifully decorated pottery. These include many intricate patterns of spirals, grids, and animal drawings, and in some cases mysterious representational figures that suggest associations with shamanism and magic... The decor of Yangshao pottery clearly possesses some aspects of symbolic representation, as well as a well developed aesthetic...We encounter interesting animal forms, both realistic and fantastic, and a justly famous pair of masklike faces with fish seemingly whispering in their ears. In addition, pottery designs include a wide variety of marks that apparently identified the potter – an early form of meaningful symbol that seems ancestral to the Chinese written script. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

According to Metropolitan Museum of Art: Painted pottery has been “found at numerous sites along the Yellow River basin, extending from Gansu Province in northwestern China to Henan Province in central China. Yangshao painted pottery was formed by stacking coils of clay into the desired shape and then smoothing the surfaces with paddles and scrapers. Pottery containers found in graves, as opposed to those excavated from the remains of dwellings, are often painted with red and black pigments. This practice demonstrates the early use of the brush for linear compositions and the suggestion of movement, establishing an ancient origin for this fundamental artistic interest in Chinese history. [Source: Department of Asian Art, "Neolithic Period in China", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. metmuseum.org\^/]

According to the Princeton University Art Museum: “By about 3000 B.C., the painted decoration begin to show undulating lines, fluid contours, and tapered endings, which indicate the use of a flexible brushlike tool. Wide-mouth bowls and basins with flat bottoms were commonly built by stacking coiled strips of rolled clay that were then smoothed before firing. This technique produced vessels characterized by a gently swelling silhouette with the upper register of the body slightly contracted below an everted rim. Such wares were used in daily life and for burial purposes.” [Source: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004 etcweb.princeton.edu |::|]

Yangshou Pottery, Cinnabar and Earliest Example of Bronze in China

Yangshao vessel lid According to the Princeton University Art Museum: “Material finds discovered at Yangshao culture sites include a variety of earthenware shards and vessels, many of which were decorated with painted designs. The paint used to decorate these pots is a fluid mixture of the same clay material as the pottery with added mineral pigments. [Source: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004 etcweb.princeton.edu |::|]

In China, the earliest known use of cinnabar (a bright red mineral consisting of mercury sulphide, sometimes used as a pigment) was by the Yangshao culture around 4000-3500 B.C.. At several sites, cinnabar covered the walls and floors in buildings used for ritual ceremonies. Cinnabar was among a range of minerals used to paint Yangshao ceramics, and, at Taosi village, cinnabar was sprinkled into elite burials.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

Eno wrote: “In addition to pottery, amidst the array of wooden, stone, and bone implements found at Yangshao sites is the earliest bronze implement yet found in China. It is a knife, dating to about 3000 B.C. Unless and until an earlier example appears elsewhere, Yangshao culture must be seen as the source of China’s transition into the Bronze Age. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu ]

Yangshou Graves and What They Say About Yangshou Society

Although early reports suggested a matriarchal culture, others argue that it was a society in transition from matriarchy to patriarchy, while still others believe it to have been patriarchal. The debate hinges on differing interpretations of burial practices. [Source: Wikipedia]

Banpo skull

Dr. Eno wrote: “The burials schemes of Yangshao cemeteries are very complex. Like the segmented village structures, graves tend to be arranged in groupings with spaces between the groups. The Yangshao people paid a lot of attention to burials.Many Yangshao graves do not reveal skeletal corpses, but instead an arrangement of bones that clearly indicates that the bodies of the dead had been dug up and ceremonially reburied. This practice, known as “secondary burial,” endures in some Chinese cultural areas today. The dead are buried in temporary graves until such time as their bodies have largely decomposed. Then the graves are opened and the bones are cleaned, before being buried once again in a final resting place. In many cases, secondary burials included the remains of many people in a single grave. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“In addition to burying many of the dead more than once, Yangshao culture demonstrated its devotion to the dead by investing considerable amounts of resources in graves. Graves were often dug as deep chambers with ledges along the walls on which pottery and other valuable objects could be placed. Sometimes the floors of the graves were paved with wooden planking and mats. In some cases, corpses were placed in wooden caskets.” /+/

Many Yangshao were buried “in the graves of the dead. The distribution of such “grave goods” indicates great distinctions in the wealth and status of grave occupants.While poorer primary burials might include only a pot or two, some of the larger graves surrounded the corpse with scores of beautifully decorated pots, fine tools, ornaments, and so forth, surely indicating the commanding role that the departed had played among the living. In the case of one large grave, almost 100 pots, joined by other objects, celebrated the grandeur of the grave occupant, whose forlorn skeleton was literally buried under opulent grave goods that had shifted on top of him over the millennia. +\

“The distinctions of wealth among the graves does not correspond to the groupings of the graves. Graves within a single group may possess very different levels of opulence, suggesting that the groupings were not determined by wealth or status, but rather by lineage relationships. The fact that among the opulent graves there are instances where the corpse was that of a child further suggests that wealth and status could be transmitted from parent to child. If we pursued these lines of speculation, they would lead towards a portrait of a society where extended lineage groups maintained ritual but not material solidarity: where within each large group, wealth was unevenly distributed, with certain lineage branches accumulating wealth and prestige that was not shared with less distinguished branches. /+/

Banpo

Among the oldest Yangshao sites is Banpo, an excavated village along the Wei river near Xian in the Shaanxi Province. Dated at 4500 B.C., Banpo was discovered in 1953 and named after a nearby village. Banpo village contains kilns for making pottery, 250 graves (including 73 for dead children buried inside earthen pots), a 300-meter-long moat, 200 storage cellars and 45 houses and other buildings. The oldest houses were built into the ground and newer ones were made with wooden frames and straw-and-mud bricks.

Banpo village is the best-known ditch-enclosed settlements of the Yangshao culture. Another major settlement called Jiangzhai was excavated out to its limits, and archaeologists found that it was completely surrounded by a ring-ditch. Both Banpo and Jiangzhai also yielded incised marks on pottery which a few have interpreted as numerals or perhaps precursors to the Chinese script, but such interpretations are not widely accepted. [Source: Wikipedia]

Banpo burial with shells

The arrangement of Banpo is fairly organized. At the center of the settlement was a 160-square meter-large one-room dwelling that was surrounded by many smaller one-room dwellings. All of the doors of these faced towards the larger dwelling, perhaps reflecting the clan organization of a group. Around the village was a 300-meter long trench or ditch that was used perhaps to keep wild animals from attacking. To the east was a ceramic-making area and to the north was the cemetery district. Inside the village were 46 houses. Some were square, some round, some half-submerged in the ground, some on the surface. These houses used traditional Chinese wood- and-earth, wall-construction methods. [Source: chinamuseums.com +++]

In a reconstruction of a Banpo dwelling at the Banpo Museum are exhibited production tools and daily utensils that were used by Banpo people. On the walls are hung animal skins and pointed-bottom vessels for getting water. A mat is spread beside the hearth on the floor. In a diorama: members of a clan, under the direction of the old grandmother, are in the process of making a fire. Outside, hunters are taking aim and firing their arrows and throwing flying balls, at frightened spotted deer. By the river, fishermen are in the process of catching fish. In the forests, women and children, holding bone spades, are gathering wild fruits. As the sun goes down, the village is alight with kitchen fires, women roast meat, grind meal using stone grinders and sew hemp-fabric clothes using bone needles. Artists are painting and impressing patterns into ceramic vessels; old grandmothers are carefully distributing the cooked food to the others: some people are putting gathered vegetables and grains into vessels for storage. +++

In the northern part of the Banpo Village is the cemetery district where adults were buried. Some 174 graves have been discovered. They are organized in lines, but exhibit different burial customs. Banpo people mostly died around the age of 30. On the eastern side of the town is the main kiln for firing pottery. Six kilns have been found to date. At the beginning, the pottery making was carried out in the open. Banpo people invented two main types of kilns: horizontal and upright ones. Banpo ceramic production used both fine-grained clay and sandy coarse clay. Three types of the fine-grained clay was used depending on its use. +++

Around twelve different kinds of markings or symbols have been found on pottery fragments or on vessels at the site. These include some of the main strokes used in Chinese characters, such as upright, cross-wise, hooked, and so on. Writing did not exist at the time, but these marks or symbols almost certainly contained their own meanings for people at the time. A number of daily articles are exhibited in the museum, such as stone axes, finely made fishhooks, fish-bone forks, sharp bone needles, and all kinds of ornamentation made of stone, bone, and ivory.

Banpo Neolithic Site is now a tourist attraction. A sign at the site credits the people that lived there with developing religion. The sign reads: "People in this primitive society with low productivity couldn't understand the structure of the human body, living and dying and many phenomena of nature, so they began to have an initial religious idea."

See Separate Article NEAR XIAN: TOMBS, NEOLITHIC VILLAGES, IMPERIAL POOLS, SACRED HUASHAN AND THE WORLD’S SCARIEST HIKE factsanddetails.com

Majiayao Culture (3800–2000 B.C.)

Early Majiayao water container

The Yangshao culture emerged in the central plain of the Yellow River. A related culture that emerged in the northwest is known as the Majiayao culture. Periods of Majiayao culture included Majiayao (ca. 3100–ca. 2700 B.C.), Banshan (ca. 2600–ca. 2300 B.C.), and Machang (ca. 2200–ca. 2000 B.C.) phases, each categorized by the types of pottery produced. Majiayao culture sites are distributed from Shaanxi province westward along the Wei River to Lanzhou, Gansu province, and along the upper reaches of the Yellow River and into Qinghai province. [Source: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004 etcweb.princeton.edu |::|]

While most Majiayao Culture settlements were along the upper reaches of the Yellow River, sites have also been found along the Yao River, the Huangshui river and the Daxiahe River. The region of the Majiaoyao overlaps with both the Yangshao culture and the Longshan culture. It developed later than the Yangshao culture and succeeded the Miaodigou. Dates for any of these cultures are approximate and various sources give 3400 - 2000 B.C. (the museums) or 3100 to 2700 B.C. (Liu Li, The Chinese Neolithic). The earliest metal work objects in China have been found within the Majiaoyao precincts. Their location near the mountains of Gansu which have rich metal deposits as well as the cultural diversity of the Yellow River basin combined to give them a head start on the bronze age. [Source: /hua.umf.maine.edu]

According to some scholars there are four subcultures within the Majiayao culture: Shilingxia, Maojiayao, Banshan and Machang. Each has variations in its pottery and cultural artifacts but they share a commonality of pattern, design, and technique. While a superficial glance at the different Neolithic potteries from different cultures might group them as a whole, there is a distinct and consistent difference in the design characteristics that allows identification of the cultural source. The swirls and smooth intertwining of curved lines and large circles is characteristic of Majiayao culture. They used a heavy black paint and on many of their pots the majority of the pot was painted black with the reveal creating the design (see the bottom left corner of the picture).

According to the Princeton University Art Museum: “Majiayao phase pottery typically has a red-buff earthenware body with a smoothed surface often finished with black painted decoration, including complicated running-spiral designs with two to four arms. Majiayao pots vary greatly in shape, ranging from bowls to jars with tall necks. The Banshan phase has a narrower range of pottery shapes and designs. Its large earthenware pots and urns often have designs in black and maroon-red paint on their shoulders. This use of two colors is a chief distinction between Banshan and Majiayao painted pottery.”|::|

New Insights Into the Majiayao Culture

In a review of the dissertation “Pottery Production, Mortuary Practice, and Social Complexity in the Majiayao Culture, NW China (ca. 5300–4000 BP),” by Ling-yu Hung, Andrew Womack of Yale University wrote: “Ling-yu Hung’s dissertation focusing on the pottery of the late Neolithic Majiayao Culture of northwest China provides fresh insights into the complexity and variation of this culture by utilizing new methods of ceramic analysis paired with theories of craft production, distribution, and consumption. The results allows her to infer that the Majiayao populations expanded during the first three sub-phases of the Majiayao phase before contracting in the final one. After discussing the Majiayao settlement of Linjia, Hung turns towards the Majiayao-type painted pottery, which despite its wide distribution is rather homogenous in form and decorative style throughout the region, thus suggesting significant interregional interaction. [Source: A review of the dissertation “Pottery Production, Mortuary Practice, and Social Complexity in the Majiayao Culture, NW China (ca. 5300–4000 BP),” by Ling-yu Hung. Review by Andrew Womack, Department of Anthropology, Yale University, Asian Archaeology China, January 20, 2014 +|+]

“Using a combination of literature, analysis of primary material, and ethnoarchaeological research in Northwest China, Hung describes in minute detail the processes that were likely involved in making a Majiayao vessel as well as the variations that occur throughout the various subphases. She concludes that the artists who produced these vessels must have spent significant time on each item and had to be highly trained to ensure that their vessels were acceptable for Majiayao consumers. Additionally, there seems to be a decline in both quality and quantity of ceramic production during the last Majiayao subphase. Overall, there is striking continuity in both form and design throughout the period and throughout the many different regions occupied by Majiayao peoples. One difference pointed out by the author is that regions outside of central Gansu and the Huangshui River valley in Qinghai have lower percentages of painted ceramics, which Hung associates with possible regional differences in cultural developments. +|+

In a section on burial practices of the Majiayao culture, the author points out that it is generally agreed that burial practices, and specifically burial positions, are related to different cultural groups inhabiting this region. Hung holds that while all groups gave painted pottery to their deceased, immigrant groups offered more vessels than indigenous groups. +|+

Majiayao female figure

“In chapter 3, the author argues based on settlement data that there was a population decrease between the Majiayao and Banshan phases, while regional diversity of the ceramic assemblages increased during the Banshan phase. Size and number of painted vessels in graves also decreased, and in peripheral areas quality decreased as well, especially during the early Banshan phase. Furthermore, by the middle period the quantity of ceramics produced at larger settlements in the central regions increased. Based on the difference in burial posture between the different regions, which she sees as a sign of a lack of migration, Hung also argues that pottery was exported from this central region to the periphery. Furthermore, she holds that high-quality ceramics could not have been produced locally in these outlying areas. On the other hand, Hung argues that other shared burial practices indicate significant regional interaction, but not actual migration. +|+

“In chapter 4, which concentrates on the Machang phase, the author discusses a significant regional diversity in painted ceramics, settlement patterns, and mortuary practices. She is able to show that during this phase the previously peripheral Huangshui River Valley in Qinghai became a main center of site distribution during the Machang Phase. This may have been due to migration from Central Gansu, since burial positions typical for the groups from Central Gansu now appear in the Huangshui River Valley. Hung furthermore argues that agriculture spread at the same time. Additionally, increased demand for mortuary ceramics was met by increased production paired with a reduction in vessel quality. Interestingly, painted designs were still not entirely mass produced, but all vessels had unique designs. Hung’s physiochemical analysis on Machang vessels suggests that increased demand for vessels was also met by increased exchange of painted vessels. Vessels were primarily exported from regions with a denser settlement covers to less populated areas. +|+

“Overall, chapters 2, 3, and 4 thus provide an overview of all three Majiayao phases by evaluating previous research and presenting new results including settlement-size studies and physiochemical, petrographic, and stylistic analysis of painted ceramics. Based on this material, Hung argues that the Majiayao period witnessed significant changes in population numbers, settlement patterns, exchange patterns, and social relations; she therefore is able to show that the painted ceramics provide an excellent window on past developments of the Majiayao culture. +|+

“In the concluding chapter 5, Hung provides a comprehensive overview of her results. As a first step, she traces the connection between settlement pattern shifts and painted ceramic production and their changes over time, concluding that painted pottery production remained most intense around core settlement areas throughout all phases. Secondly, Hung describes three regional groups that inhabited the research area during the Majiayao phase, identifying them through differences in burial postures. In some cases these groups are associated with specific burial pottery. +|+

“Based on these results, Hung suggests a new model for the production and distribution of painted pottery that treats painted pottery vessels as commodities. Hung argues that these commodities were produced in kin-based groups, but that the distribution and exchange may have taken place in a variety of economic situations. As vessels from diverse origins were found in single tombs, indicating exchange with multiple production groups, Hung argues for inter-kin group exchange. Additionally, some groups seem to have had a wider range than others. The author furthermore holds that the number of painted ceramics produced in the core settlement regions was higher than in the periphery, simply because the core area had a higher agricultural output, allowing for a greater division of labor and the specialization of part of the population on ceramic production.” +|+

Qijia culture (ca. 2200–ca. 1800 B.C.)

According to the Princeton University Art Museum: “The Qijia archaeological culture was discovered in 1923 by the Swedish archaeologist and geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960) along the Tao River in Gansu province, but it was only recognized in 1924 and named after a site at Qijiaping, Guanghe county, Gansu. Qijia succeeded Majiayao culture at the end of the third millennium B.C. at sites in three main geographic zones: Eastern Gansu, Middle Gansu, and Western Gansu/Eastern Qinghai. In addition, Qijia sites were also found in Ningxia province and Inner Mongolia. Cold-hammered and cast metal utensils and mirrors have also been found at Qijia sites, showing that Qijia culture was in a transitional stage between Neolithic and Bronze Age development. [Source: Princeton University Art Museum, 2004 etcweb.princeton.edu ]

Qijia pottery featured unpainted vessels with flat bottoms, and bodies of an orange-yellow or red-brown clay. Common Qijia vessel types include one- and two-handled jars, and large-mouth jars. The distinctive broad, arched, strap handles and rivet-like details characteristic of Qijia ceramics are imitative of sheet-metal work, and suggests the existence of metal vessels at this time. There were also examples of Qijia painted pottery, especially in Western Gansu and Eastern Qinghai.

Image Sources: Yangshao lid, Ohio State University; Banpo Site, Banpo webiste; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016