FIRES REPLACE RAIN DURING THE AMAZON WET SEASON

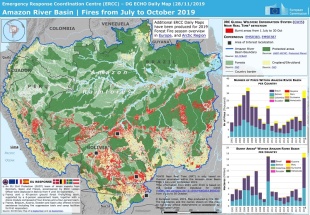

In March 2024, Ana Ionova and Manuela Andreoni wrote in The New York Times: By this time of the year, rain should be drenching large swaths of the Amazon rainforest. Instead, a punishing drought has kept the rains at bay, creating dry conditions for fires that have engulfed hundreds of square miles of the rainforest that do not usually burn. The fires have turned the end of the dry season in the northern part of the giant rainforest into a crisis. Firefighters have struggled to contain enormous blazes that have sent choking smoke into cities across South America. A record number of fires so far this year in the Amazon has also raised questions about what may be in store for the world’s biggest tropical rainforest when the dry season starts in June in the far larger southern part of the jungle. [Source: Ana Ionova and Manuela Andreoni, The New York Times, March 11, 2024]

In February 2024, Venezuela, northern Brazil, Guyana and Suriname, which encompass vast stretches of the northern Amazon, recorded the highest number of fires for any February, according to Brazil’s National Institute of Space Research, which has been tracking fires in the rainforest for 25 years. Fires also burned across Colombia’s Andes highlands, as well as parts of that country’s Amazon territory.

The fires in the Amazon, which reaches across nine South American nations, are the result of an extreme drought fueled by climate change, experts said. The region has been feeling the effects of a natural weather phenomenon known as El Nino, which can worsen dry conditions that were intensified this year by extremely high temperatures. That has made the rainforest more vulnerable to fast-spreading blazes, said Ane Alencar, the science director at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute in Brazil. “The climate is leaving forests in South America more flammable,” she said. “It’s creating opportunities for wildfires.”

In January, wildfires burned almost 4,000 square miles of the Brazilian Amazon, an almost fourfold increase from the same month last year, according to Mapbiomas, a collective of climate-focused nonprofit organizations and research institutions. In February, more than two-thirds of the fires in Brazil have occurred in Roraima, the country’s northernmost state. They have burned homes and subsistence crops in several Indigenous villages, leaving a thick haze over rural areas and creating hazardous air quality in the state’s capital, Boa Vista.

As a result of the prolonged drought, the vegetation in this part of the Amazon has become “combustible,” Alencar explained. “Roraima is like a barrel of gunpowder right now.” Researchers say that most of the fires sweeping through the region were initially set by farmers using the “slash and burn” method to allow new grass to grow on degraded pastures or to fully clear recently deforested land. Fueled by the dry conditions and searing temperatures, many of these fires burn out of control, spreading miles beyond the area that was originally set ablaze. “Fires are contagious,” Flores said. “They modify the ecosystem they pass through and increase the risk for neighboring areas like a virus.”

In Roraima, the blazes have mostly burned areas within the Lavrado, a unique savannalike region nestled within the Amazon, said Erika Berenguer, a senior research associate at the University of Oxford and at Lancaster University. After months of scarce rains, dense rainforest that is typically too humid to catch fire has also become more susceptible to flames. In Roraima, the fires have now spread to protected forests and Indigenous lands in the southern region of the state, according to Haron Xaud, a professor at the Federal University of Roraima and a researcher at Embrapa Roraima, an institute monitoring the fires.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION: RATES, RESULTS AND ALARM factsanddetails.com ;

CAUSES OF RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

SLASH-AND-BURN AGRICULTURE (SWIDDEN) factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LUMBER AND TIMBER AND PAPER COMPANIES factsanddetails.com ;

RUBBER: PRODUCERS, TAPPERS AND THE RAIN FOREST factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL: USES, HISTORY, AGRICULTURE AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL BUSINESS: PRODUCERS, COMPANIES, IMPORTERS factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL AND RAIN FOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

COMBATING DEFORESTATION AND EFFORTS TO SAVE THE RAINFOREST factsanddetails.com ;

NEW JUNGLES AND REFORESTATION factsanddetails.com

Impact of Fires and Drought on the Amazon and the World

The Amazon stores vast quantities of carbon dioxide in its trees and soil and is also home to 10 percent of the planet’s plants, animals and other living organisms. Ana Ionova and Manuela Andreoni wrote in The New York Times: While fires are common in drier boreal forests in Canada and other parts of the Northern Hemisphere, they do not naturally occur in the much-wetter Amazon rainforest. Tropical forests are not adapted to fires, Xaud said, “and degrade much faster, especially if the fire becomes recurrent.” [Source: Ana Ionova and Manuela Andreoni, The New York Times, March 11, 2024]

If deforestation, fires and climate change continue to worsen, large stretches of the forest could transform into grasslands or weakened ecosystems in the coming decades. That, scientists say, would trigger a collapse that could send up to 20 years’ worth of global carbon emissions into the atmosphere, an enormous blow to the struggle to contain climate change. Once this tipping point is crossed, “it may be useless to try to do something,” said Bernardo Flores, who studies the resilience of ecosystems at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil.

Some of the wildfires started by humans in the Amazon have grown into “megafires,” typically defined as blazes that burn more than 100,000 acres of land or that have an unusually significant effect on people and the environment. These kinds of fires, Flores said, will become more frequent as the planet warms and deforestation damages the Amazon’s ability to recover.

Environmental factors are already changing the Amazon. Dry seasons are becoming longer, and average rainfall during those periods, when rains diminish but do not stop altogether, has already dropped by one-third since the 1970s, Berenguer said. That has made El Ninos increasingly dangerous. “When you have all of these factors together, you have the conditions for a perfect storm — the perfect firestorm, that is,” Berenguer said.

The fires in the Amazon region have had a striking effect on carbon emissions. In February, wildfires in Brazil and Venezuela emitted almost 10 million tons of carbon, the most ever recorded for the month and about as much as Switzerland emits in a year, according to data from Europe’s Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service. The El Nino pattern should wind down in a few months, bringing some respite to the Amazon.

But more devastating fires could erupt if the parched soil does not receive enough rainfall in the crucial wetter months ahead, Alencar said.“The question is whether the forest can recover before the dry season, whether the Amazon can recharge its batteries,” Alencar said. “Now it all depends on the rains.”

Is the Amazon Reaching a Tipping Point?

Robert Walker, a quantitative geographer at the University of Florida’s Center for Latin American studies, has said that unless something unprecedented happens, the Amazon will be wiped out by 2064. Stephen Eisenhammer of Reuters wrote: “As more and more of the forest is cut down, researchers say the loss of canopy risks hitting a limit — a tipping point — after which the forest and local climate will have changed so radically as to trigger the death of the Amazon as rainforest. In its place would grow a shorter, drier forest or savannah. The consequences for biodiversity and climate change would be devastating, extinguishing thousands of species and releasing such a colossal quantity of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that it would sabotage attempts to limit global climate change. “The Amazon tipping point would mark a final shift in the rainforest's ability to sustain itself, an inflection point after which the trees can no longer feed traversing clouds with enough moisture to create the quantities of rain required to survive. [Source: Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters, October 23, 2021]

“Climate models have foreseen other so-called tipping points disrupting Earth's long-balanced systems, for example warming that causes Siberian permafrost to thaw and release huge amounts of emissions, or Greenland's Ice Sheet melting at such a rate that annual snowfall can no longer make up for the loss. Exactly where that point is in the Amazon, science is not yet decided. Some researchers argue that current modeling isn't sophisticated enough to predict such a moment at all. But evidence is mounting that in certain areas, localized iterations of the tipping point may already be happening. If the tipping point marks the irreversible march of savannah over rainforest, scientists predict the process would first occur in forests where savannah and rainforest are already intertwined.

“Celebrated Brazilian climatologist Carlos Nobre, who has helped popularize the idea of the tipping point, puts the precipice at between 20 percent and 25 percent deforestation of the original Amazon canopy. We are currently at about 17 percent, according to the major report with 200 scientists published in 2021. Nobre believes we could see mass dieback across eastern, southern and central Amazonia within as little as 15 years.

“Others aren't so sure. Marina Hirota, an earth system scientist who worked on models before switching to field work, says current simulations oversimplify the diverse vegetation, soil type and topography found across the Amazon basin. In her view, there's not yet enough evidence to say where the tipping point is or even if such a single threshold exists for sure. The models need to be improved first, she says. Hirota considers it more likely that deforestation would trigger multiple smaller tipping points in different locations across the Amazon. But many scientists think putting a single number on the tipping point is still important as a clarion call, even if it's too complex to currently prove. Once you're able to prove it, ecologist Paulo Brando argues, it will already be too late. "We know there's a cliff out there, and so even if we're not exactly sure where it is, we need to slow down," Brando says. "Instead, we're rushing towards it with our eyes closed."

Ecologists Ben Hur Marimon Jr. and Beatriz Marimon conduct research at the local campus of the Mato Grosso State University in Nova Xavantina, a soy town of 20,000 people in the southern Brazilian Amazon, in a biome borderland, an in-between space where the Cerrado savannah transitions into the Amazon rainforest. The trees that remain, they say, offer a vision of the future. "This is tomorrow, today," Beatriz says, crunching through a dry patch of forest on the edge of town. Ben Hur finishes the thought. "This is the border of the Amazon, its protective wall, and it's dying."

“To monitor the forests, the couple tag trees of varying sizes and species across their plots with bits of metal that look like military dog tags. They return at regular intervals — anything from three months to three years — and measure tree circumference, height and carbon dioxide respiration. Trees that haven't made it are added to a list of the dead." In many cases the old, big trees do okay. It is the younger ones that struggle. "For Ben Hur and Beatriz, the degrading forests around Nova Xavantina demonstrate that the tipping point may already be happening there on a local level. The major question remains whether this same process could occur on a huge scale over entire swaths of the Amazon basin — and if so, when?

cloud forest, secondary forest and farm land in Ecuador

Drying of the Amazon

Scientists have predicted that once the Amazon looses more than 25 percent of its tree cover, it might permanently become a drier ecosystem, because deforestation changes weather patterns due to how trees respire, which in turn reduces rainfall. On top of this, as the forest becomes fragmented, areas surrounded by savanahs, farms and ranches will lose species in a process called “ecosystem decay.” [Source: Kim Heacox, The Guardian, October 7, 2021]

Stephen Eisenhammer of Reuters wrote: “Brazil is blessed with the largest freshwater reserves in the world. But the relentless rise of one of the world's agricultural powerhouses combined with changes in global climate are helping to drive a loss of this vital resource. Data released in 2021 by MapBiomas, a collaboration between universities, nonprofit groups and technology companies, found Brazil lost 15 percent of its surface water in the three decades prior to 2020. [Source: Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters, October 23, 2021]

Several scientific studies have found the same. Because tropical forests influence rainfall, deforestation can change their pattern. One influential 2011 paper looking at 30 years of precipitation data found that the onset of rains in Rondonia state had been delayed by up to 18 days. Research since then has backed up this trend. A major report this year, which brought together around 200 scientists, said available data pointed to a dry season that "has expanded by about one month in the southern Amazon region since the middle 1970's."

Large-scale deforestation disrupts” self-generating-rain processes of the Amazon, “reducing the number of trees to such an extent that precipitation levels fall or become more concentrated over a shorter wet season. In some parts of wide-ranging Nova Xavantina over the past 30 years, rainfall has fallen by as much as 30 percent. As precipitation changes, streams and sources disappear, and the remaining forest turns drier. Local temperatures also increase — particularly on edges where forest and farmland meet. Those vast flat agricultural clearings increase the strength of winds, which can rip through woodland and tear down the tallest, oldest trees. The drier forest is also more vulnerable to fire, which is still widely used for clearing farmland here. As more trees die — from wind, drought and fire — their deaths increase the likelihood of such extreme weather in the future, creating a deadly feedback loop.

“Early experiments that mimicked extreme drought in the Amazon had led scientists to think the drier climate would kill older trees first, but: since then scientists “have found is the opposite. With longer roots, the largest trees are usually the most resilient — at least to drought. Instead, it's the saplings that die. The forest loses its future.

“Antonio Deuseminio, an agroecologist with decades of experience in the rainforest, is helping farmers replant trees and bring water back to their properties. He works for a subdivision of the Ministry of Agriculture focused on cacao, which he says has the oldest weather data in the area. Although total rainfall hasn't changed significantly in Ouro Preto do Oeste, the dry season has gotten longer and drier, Deuseminio says. For agriculture this is a serious problem, because crops and grasses don't have long enough roots to find water when there's no rain. The drier climate makes reforesting harder too. Twenty years ago, rainforest species could be planted straight into the bare soil. Deuseminio says he must now first plant drought-resistant trees, and only once these have grown enough to provide shade and improve the soil, after five years or so, can he follow up with classic Amazon species. Rainforest saplings now struggle to survive, he says, in this part of the Amazon.

Columbia

Parts of the Amazon That Have Already Dried Out

Reporting from Ouro Preto Do Oeste, Brazil, in the Brazilian state of Rondônia, Stephen Eisenhammer of Reuters wrote: Gertrudes Freire and her family came to the great forest in search of land and rain. They found both in abundance, but the green wilds of the southwestern Amazon would prove tough to tame. When they reached the settlement of Ouro Preto do Oeste in 1971, it was little more than a lonely rubber-tapper outpost hugging the single main road that ran through the jungle like a red dust scar. Her children remember the fear. Fear of forest jaguars, indigenous tribes and the mythological Curupira: a creature with backward-turned feet who misleads unwelcome visitors to leave them lost among the trees. [Source: Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters, October 23, 2021]

“The family carved their home from the forest. They built their walls from the tough trunks of the cashapona tree and thatched a leaky roof from the broad palms of the babassu. There was no electricity, and some days the only food was foraged Brazil nuts. At night, in hungry darkness they would listen to the cascading rain. Life was damp. Until it wasn't. Near the Freire home, there was a stream so wide that the children would dare each other to reach the other side. They called it Jaguar's Creek. Now it's not a meter wide and can be cleared with a single step. The loss of such streams, and the wider water problems they are a part of, fill scientists with foreboding.

“Year after year, the Freire family hacked and sawed farther into their patch of forest on Brazil's western frontier. In 1976, after clearing a couple of hectares and getting permission to use some of their neighbor's pasture too, they invested in 10 heifer calves and a bull — the start of a dairy business that would over the years grow into a successful herd of about 400 head. But a fear of drought haunted their work.

“For the Freires, the last bits of doubt about the drying of the land seeped away on a parched day in 1991. A cowhand told Gertrudes the cattle were so thirsty, they were nuzzling the bottom of dried-out springs, sucking the sand in search of moisture. She acted swiftly and put in a complex system of pipes and pumps to draw water for the cattle from springs that had not yet gone dry.

“Controversially, she began reforesting too. Gertrudes had little idea of what she was doing but trusted her instincts, sharpened by years of drought in the homeland she'd abandoned. Her neighbors — and husband — thought she was crazy as she planted trees around water sources and along streams and vowed that the last remaining patch of virgin forest, at the far end of the property, should remain intact. Her words weren't always heeded. "I came back from one short trip away and my husband had cleared another patch" for pasture, she remembers, shaking her head.

“Gertrudes sensed that rainfall was changing too.” In 2021 “the Freires bemoan the driest dry season any of them can remember. It is mid-August, and the first rains used to come by now, they say. The dry season, once just three months, now stretches for four or five. Across the whole country, reservoirs are dangerously low as Brazil suffers one of its worst droughts in a century. The family is diversifying to try and shield their business from drought, building out capacity in breeding and beef cattle to complement their milk production. They've also started an organic soap business and want to plant corn.

“Water is a constant worry. Some nearby farmers have already sold their land — mostly to larger cattle ranchers who address the problem by digging deep wells or piping water over long distances. "It's going to get even drier," says Gertrudes, looking out over her farm's yellow grass as two cats laze comatose in the stifling afternoon heat. In the distance, smoke hazes the horizon as newly slashed forest burns. "The water will finish."

Deforested Amazon Producing Rather Than Absorbing CO 2

Stephen Eisenhammer of Reuters wrote: “Since the Industrial Revolution, scientists estimate that roughly a quarter of all fossil fuel emissions have been absorbed by forests and other land vegetation and soils, chief among them the Amazon. Through the 1980s and 1990s, as mass human migration to the Amazon was just beginning, the rainforest drew down some 500 million tons of carbon from the atmosphere every year, more than the current annual emissions of Germany, Britain, Italy and France combined. Photosynthesis by the forests' billions of trees, using carbon dioxide to live and grow, served as a vital buffer against climate change. As migration increased and more of the Amazon was cleared for agriculture, scientists knew the forest's ability to suck in carbon would be hit. But no one knew quite how much. [Source: Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters, October 23, 2021]

Atmospheric chemist Luciana Gatti, who works for INPE, Brazil's space research agency, measures carbon dioxide in the skies above the Amazon and find out how much the forest aborbs. “To try and get an answer, Gatti squeezed into a roaring single-engine four-seater plane armed with a padded suitcase packed with glass flasks. From up over the canopy, she could sometimes see the scale of destruction, the gray smoke billowing from burning trees and the yellow patches of earth shorn of the forest green. Gatti's earliest air samples date back to 2000, from a single point in the eastern Amazon. But she found the data too narrow and volatile to give a picture of the carbon balance for the whole basin, so over the following years she expanded the work, training teams and contracting light aircraft to fill flasks of forest air from four parts of the Amazon: Santarem and Alta Floresta in the east and Tefe and Rio Branco in the west.

“Since then, the aircraft have taken more than 600 vertical profiles — a series of samples taken at different altitudes over a given spot. At one point Gatti doubted her results. She grew depressed. The data didn't make sense. It couldn't be true. It showed the southeastern Amazon was releasing more carbon that it was absorbing, even in rainy years when scientists had expected the forest to be in better health. It meant a part of the rainforest was no longer helping to slow climate change, but adding to the emissions driving it.

“She changed her methodology. Changed it again. And again. In total, she went through seven methodologies before eventually accepting what had seemed impossible. The southeastern Amazon is not only a net producer of carbon, but even when you strip out the fires, the forest alone — or the non-fire net biome exchange — is a carbon source. Scientists widely regard the results, recently published in Nature, as the most definitive so far on the changing carbon fluxes of the rainforest.

“The western part of the Amazon, protected by its remoteness, is in better health and can still absorb substantial amounts of carbon, the study shows. But it's not enough to compensate for the polluting east, where ranching and soy farming have cut deep into the rainforest. The so-called lungs of the Earth are coughing up smoke. "We are losing the southeastern part of the forest," Gatti says.

“Gatti thinks her numbers show that certain parts of the Amazon may already be at their tipping point. She believes the data points to the same process that Ben Hur and Beatriz have witnessed, but on a greater scale: Rainforest species such as the brazil nut and the ironwood giving way to trees like mabea fistulifera and ouratea discophora that are more tolerant of the drier, hotter climate. Such regime change releases huge quantities of carbon and would help explain the forest's flagging ability to draw down emissions. "It is a path without return," Gatti says.

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com ; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2024