PALM OIL BUSINESS

Palm oil palm in Malaysia The palm oil industry was worth about $40 billion in 2016 according to Smithsonian magazine. By 2022, the global market for palm oil was expected to more than double in value to $88 billion.

Natasha Gilbert wrote in Nature: Even as the environmental case against it grows stronger, the palm-oil business is booming as never before. “Oil palm is such a lucrative crop that there is almost no way to stop it,” says William Laurance, a forest-conservation scientist at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia. Indonesia is expected to double production between 2012 and 2030. In June 2012, the Malaysian palm-oil company Felda Global Ventures (FGV) earned US$3.2 billion in the second-largest initial public offering (IPO) this year after Facebook, which will enable the company to bring thousands of extra hectares into production. Sabri Ahmad, group president of FGV, told reporters that the company planned to expand its operations eightfold in eight years. To do so, it will have to look beyond Malaysia to countries such as Cambodia and Indonesia. [Source: Natasha Gilbert, Nature, July 4, 2012]

Palm oil is more profitable than rubber, generally selling for more per ton on the world market. Oil palms produce 3.7 tons of oil per hectare per year, compared to 0.6 tons for rapeseed, 0.5 tons for sunflower and 0.4 tons for soybeans. Palm oil competes with soy oil for dominance in the edible oil category. Palm oil is the world's second best selling vegetable oil (16 percent of the world's output) after soy bean oil (20 percent). The prices of palm oil rise and fall with the demand for edible oils. The average price per ton for palm oil was:$780 in 2007 and $949 in 2008.

An aggressive campaign to increase palm oil production was launched in the 1960s to reduce Malaysia's dependency on tin and rubber. Thousands of square miles of virgin rain forest have been cut down since then to make way for palm oil plantations. Palm oil prices are quoted in dollars. Palm oil became very profitable in Malaysia and Indonesia as the value of the currencies there crashed after the Asian economic crisis in 1997-98. The idea of palm oil being used as an automobile fuel was proposed by a farmers as a solution for the problem of declining demand for palm oil caused by health concerns.

RELATED ARTICLES:

PALM OIL: USES, HISTORY, AGRICULTURE AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL AND RAIN FOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION: RATES, RESULTS AND ALARM factsanddetails.com ;

CAUSES OF RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

DROUGHT AND FIRE: IS THE AMAZON DRYING OUT? factsanddetails.com ;

COMBATING DEFORESTATION AND EFFORTS TO SAVE THE RAINFOREST factsanddetails.com

Palm Oil Companies

World’s leading palm oil companies in 2021, based on market capitalization(in million U.S. dollars) were: 1) IOI (2,8082,808): 2) Sime Darby Plantation (2,8082,808): 3) Wilmar International Limited (2,7782,778); 4) Kuala Lumpur Kepong (2,4592,459); and 5) Golden Agri-Resources (1,1531,153). [Source: Statista]

According to IOI’s website: IOI Corporation Berhad (IOI) is a leading global integrated and sustainable palm oil player. We are listed on the Main Market of Bursa Malaysia Securities Berhad and trading as MYX: 1961. Our operations consist of the plantation business which covers Malaysia and Indonesia, while our downstream resource-based manufacturing business includes refining of palm oil as well as manufacturing of oleochemical and specialty oils and fats, which has a growing presence in Asia, Europe and USA.

According to its website, "Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) is a vertically-integrated palm oil plantation company with a commitment to responsible palm oil. In Indonesia, our primary activities include cultivating and harvesting oil palm trees; extracting fresh fruit bunches (FFB) into crude palm oil (CPO) and palm kernel; to processing it into value-added products such as cooking oil, margarine, shortening, biodiesel and oleochemicals; as well as merchandising palm products throughout the world."

During the past decade, environmentalist have said that a growing number of palm oil companies have accepted the need for change. RSPO CEO Darrel Webber told National Geographic: “We’ve got quite a few in acceptance but also quite a few in denial. Our job is to push this long tail of producers into acceptance. It will take a while.” [Source: Hillary Rosner, National Geographic, December 2018]

For information on Wilmar and Sime Darby See Separate Article on PALM OIL AND MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Lee Shin Chen and IOI

Lee Shin Cheng (1939–2019) was the Founder and Executive Chairman of IOI Corporation Berhad and IOI Properties Group Berhad. He was born in Jeram, Kuala Selangor, Malaysia in 1939. As a child, he was raised in a rubber estate where his father owned a sundry shop. At the age of only 11, he had to stop schooling and sell ice-cream full time on his own bicycle in order to help support his family. He did this for three years before he went back to school to complete his studies at Middle High School. [Source: IOI website]

palm wine made from the nipa palm, not palm oil Tan Sri Dato’ Lee started working at the age of 17, as a supervisor in a rubber estate. He diligently worked his way up to become a full-fledged estate manager before he turned 30 years old. In 1975, Tan Sri Dato’ Lee started a private-limited property company named Lam Soon Huat Development Sdn Bhd (later renamed as IOI Properties Berhad in 1994). In 1982, he secured a controlling stake in Industrial Oxygen Incorporated (“IOI”) and used it as a vehicle to venture into oil palm plantation business starting from zero base. In the following year, he acquired three plantation companies in Pahang and later ventured into greenfield oil palm planting in Sabah through the acquisition of Morisem Plantation (Sabah) Sdn Bhd.

In 1990, he acquired Dunlop Estates, a business much bigger than IOI at that time. The acquisition marked the first major breakthrough in his life, and became one of the proudest moments for him. There is an added irony in that he applied for a job at Dunlop Estates 25 years earlier but was rejected due to lack of education qualifications. The RM500 million acquisition involved 13 palm oil estates (a total of 27,880 hectares), two palm oil mills, two rubber factories and one Research Centre.

Tan Sri Dato’ Lee’s other significant milestone involved the acquisition of Pamol Plantation Sdn Bhd in 2003 from Unilever. Since then, the breeding and seed production operation of Pamol became integrated with IOI Research Centre, which enables IOI to produce very high-quality seeds for its plantations. In 1997, he acquired a controlling stake in Palmco Holdings Berhad (later renamed as IOI Oleochemical Industries Berhad), a palm-based oleochemical company. Within one year of acquiring the struggling company, Tan Sri Dato’ Lee turned it around into a highly profitable business by expanding the market base of its product globally. Nine years later, he acquired Pan-Century Edible Oils and Pan-Century Oleochemical, making IOI the world’s largest vegetable-based oleochemical producer at that time. In 2002, Tan Sri Dato’ Lee further diversified his businesses and extended his reach globally by acquiring Loders Croklaan, a specialty fats company based in the Netherlands and with operations in the United States and Canada, from Unilever. The acquisition provided IOI access to the specialty oils and fats markets in over 60 countries and completed IOI’s palm oil value chain, making it a leading global integrated palm oil producer.

Impact of Chinese Demand for Palm Oil on Malaysia and China

Demand from China for palm oil has caused the price of palm oil to rise dramatically, which in turns has affected a number of businesses and caused farmers to make changes in the crops they grow. Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “That surge in sales of palm oil is, in Malaysia in particular, creating dramatic social change overnight. Government coffers are so full that last month all civil servants — everyone from deputy public prosecutors to ministry cooks — were given pay rises of between 7.5 percent and 42 percent. The one-off windfall was their first salary increase since 1992 and cost the Government £1.1 billion. To make life even sweeter, the cost-of-living allowance for the same workers — who represent about a tenth of the country’s workforce — was doubled.[Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, August 25, 2007 +*+]

“Suddenly, people in one of Malaysia’s most underpaid and conservative sectors are talking about dipping their toes in the stock market, buying homes and upgrading their lifestyles.Rhosdi, for instance, a state-school teacher in his 30s, is able to think about the social advance involved in swapping two wheels for four. Envious of the civil servants’ good fortune, private sector employees have begun lobbying for similar pay rises. Tellers at branches of Maybank in Kuala Lumpur have begun wearing prominent signs around their necks demanding that management “match the civil servants’ increase”. +*+

“In this complex train of economic cause and effect, there is another butterfly flapping its wings in Beijing in the shape of Liu Ping. She used to buy her monthly quota of half a pound of oil for the three members of her family with a ration coupon. “The oil just about filled a beer bottle and we had to make do for a month.” That was in the 1960s and 1970s, when the family used to steam most of their food. “We just didn’t cook dishes that needed lots of oil, like eggplant or beans.” Some people used lard even in the 1980s when oil was at last available in the shops, but at a cost of 1 yuan per kilo – a lot for the average family living on 40 yuan a month. Now Mrs Liu, 60, uses about 6 catties (pounds) of oil a month to cook for her husband and daughter, underlining how economic growth in China — and India — has created vast new markets for edible oils, particularly soya and palm oil. +*+

“Diets in China and India have changed out of recognition as prosperity has grown, creating greater demands for meat and, as a consequence, the crops that feed livestock. “But it is corn and edible oils where the greatest impact is being be felt. As the billion-strong populations of both countries gradually rise from poverty, vegetable oils –– an extremely expensive proportion of the average developing world diet –– have formed a greater part of everyday meals. In Beijing, a ten-litre bottle of oil costs about 80 yuan — inexpensive for today’s new-rich city dwellers and affordable even to China’s farmers. Within a year, say economists, China could reach the hugely significant point of becoming a net importer of corn. Oils give food a sophistication that more and more Chinese and Indians are getting a taste for.” +*+

Palm Oil as a Measure of the Global Markets

Leo Lewis wrote in The Times, “For years, economists, along with everyone else, thought of palm oil as exactly what it looked like: a pinkish, sludgy irrelevance. People knew that it was used to make food and soap but everything else about it, including its origins, seemed slightly distasteful. In 2009 palm oil has not changed its colour or texture, but as an economic indicator it is unrecognisable. In a world of food and energy crises, of credit implosions, green politics and the rise of Asia, it has become the gauge that straddles them all — the ultimate global speedometer. [Source: Leo Lewis. The Times, August 15, 2009 ^^]

“Through its price fluctuations and ever-changing trade destinations, palm oil has become an accurate measurement of hundreds of global markets. Its versatility is the key, which is the main reason why the world consumes 42 million tonnes a year — twice as much as it did a decade ago. For all of the criticism that palm oil plantations attract for destroying the rainforest and endangering wildlife, the demand is a reading of a global population trying to feed and power itself under challenging circumstances. ^^

“The growth of palm oil has tracked the rising wealth of the middle classes in China and India, which buy up a quarter of all global supplies every year. Those who can afford to fry more of their food, and when other edible oil stocks can not keep up, or when prices rise too far, palm oil becomes the alternative. As a biofuel feedstock, palm oil can meet a similar demand with energy, offering an alternative strategy when the markets are knocked out of kilter. ^^

“Palm prices tell us how rich the average Chinese family feels at new year, and with what sort of food the Muslim world will be breaking the fast each night of Ramadan. It tells us where London brokers think crude oil prices are heading and what Chicago futures traders think of this year’s soya bean crop and how badly El Niño is hurting South-East Asia this cycle. ^^

“In Malaysia and Indonesia, which between them meet about 87 percent of the global demand, palm oil price movements dictate government policy, shape economic prospects and draw billions of dollars of direct investment. For Malaysia, palm oil competes with tourism and manufacturing as the three biggest sources of economic growth. A couple of years ago, a bumper haul and dazzling prices allowed the Government in Kuala Lumpur to give a bonus to every civil servant in the country. In Indonesia palm oil plays an even more central role in the country’s economic future. One popular view is that Indonesia belongs in three of the world’s most promising and exciting, emerging markets. The theory is backed by the idea that an industry that already employs two million people has the scope to double its output by 2014. ^^

“Perhaps most critically of all, palm oil is the canary in the mine for biofuel policy-making around the world. Setting stomachs and cars against each other in direct competition for calories is a finely balanced game, more likely to go wrong than right. A poorly calculated subsidy in one country can cause dangerous price rises in a food commodity on another continent. In almost all cases, the price of palm oil is where the folly emerged. ^^

palm oil producers

World’s Top Palm Oil Producing Countries

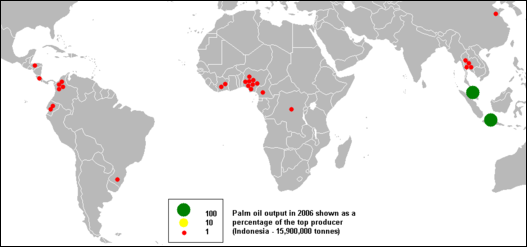

About 85 percent of the world's palm oil is produced in Indonesia and Malaysia. Malaysia for a long time was the world's biggest palm oil producer, and its companies are also big players in neighboring Indonesia. In 2002, Malaysia produced 50 percent of world palm oil, with Indonesia producing 30 percent. But Indonesia quickly caught up. According to The Times in 2009 Indonesia had 4,545,000 hectares of palms compared to 3,741,000 in Malaysia. Global production of palm oil doubled from 1996 to 2006 to 23 million tons per year, with over 10 million hectares now under plantation. Plantations of oil palm are expected to grow by 43 percent by 2025.

World’s Top Producers of Palm Oil (2019):; 1) Indonesia: 42869429 tonnes; 2) Malaysia: 19858367 tonnes; 3) Thailand: 3040000 tonnes; 4) Colombia: 1527549 tonnes; 5) Nigeria: 1220000 tonnes; 6) Guatemala: 880000 tonnes; 7) Honduras: 707000 tonnes; 8) Papua New Guinea: 578000 tonnes; 9) Cote d’Ivoire: 510000 tonnes; 10) Ecuador: 420000 tonnes; 11) Brazil: 400560 tonnes; 12) Cameroon: 300000 tonnes; 13) Democratic Republic of the Congo: 294000 tonnes; 14) Ghana: 257280 tonnes; 15) Costa Rica: 247800 tonnes; 16) Peru: 220000 tonnes; 17) Philippines: 130000 tonnes; 18) China: 112428 tonnes; 19) Mexico: 107000 tonnes; 20) Togo: 105000 tonnes ; [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org. A tonne (or metric ton) is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kilograms (kgs) or 2,204.6 pounds (lbs). A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lbs.]

Top palm-oil producing Countries in 2008: (Production, $1000; Production, metric tons, FAO): 1) Malaysia, 5369279 , 17734441; 2) Indonesia, 5116644 , 16900000; 3) Nigeria, 402670 , 1330000; 4) Thailand, 393588 , 1300000; 5) Colombia, 235486 , 777800; 6) Papua New Guinea, 115654 , 382000; 7) Ecuador, 93552 , 309000; 8) Côte d'Ivoire, 87800 , 290000; 9) Honduras, 82774 , 273400; 10) China, 68121 , 225000; 11) Brazil, 66607 , 220000; 12) Costa Rica, 58802 , 194220; 13) Cameroon, 56010 , 185000; 13) Guatemala, 56010 , 185000; 15) Democratic Republic of the Congo, 55102 , 182000; 16) Ghana, 38753 , 128000; 17) Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), 27066 , 89400; 18) Philippines, 24826 , 82000; 19) Mexico, 18771 , 62000; 20) Guinea, 15138 , 50000.

Indonesia has been the world’s largest oil palm fruit producer. In 2011, the export value of Indonesia’s oil palm products and derivatives reached $11.61 billion, up 17.75 percent, or $2.5 billion from 2010. The export value in the coming years is expected to keep growing in line with the government target of 27 million tons of oil palm fruit production in 2015.

World’s Top Palm Oil Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Palm Oil (2020):; 1) Indonesia: 25936722 tonnes; 2) Malaysia: 14575437 tonnes; 3) Netherlands: 1280283 tonnes; 4) Guatemala: 740269 tonnes; 5) Papua New Guinea: 697970 tonnes; 6) Colombia: 621186 tonnes; 7) Honduras: 471303 tonnes; 8) Germany: 309729 tonnes; 9) Costa Rica: 231957 tonnes; 10) Thailand: 219484 tonnes; 11) Turkey: 180439 tonnes; 12) Ecuador: 162655 tonnes; 13) Kenya: 155350 tonnes; 14) Togo: 126517 tonnes; 15) Italy: 116662 tonnes; 16) Ghana: 115929 tonnes; 17) Peru: 93133 tonnes; 18) United States: 89815 tonnes; 19) Côte d'Ivoire: 84911 tonnes; 20) United Arab Emirates: 83885 tonnes ; [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Palm Oil (2020):; 1) Indonesia: US$17364812,000; 2) Malaysia: US$9808525,000; 3) Netherlands: US$1070466,000; 4) Guatemala: US$465705,000; 5) Papua New Guinea: US$431966,000; 6) Colombia: US$406303,000; 7) Honduras: US$302615,000; 8) Germany: US$278891,000; 9) Thailand: US$157899,000; 10) Costa Rica: US$148393,000; 11) Italy: US$141563,000; 12) Niger: US$130000,000; 13) Ecuador: US$120240,000; 14) Turkey: US$119724,000; 15) Kenya: US$115504,000; 16) Denmark: US$104389,000; 17) United States: US$98499,000; 18) Ghana: US$98440,000; 19) United Arab Emirates: US$70748,000; 20) Oman: US$69051,000

palm plantation in Cigudeg, Indonesia

World’s Top Palm Oil Importing Countries

Global demand for palm oil continues to increase. India uses the most, 17 percent of the global total, followed by Indonesia, the European Union and China. The United States ranks eighth. In 2018 global consumption reached 72 million tons, or roughly 20 pounds of palm oil per person. In the 2000s India was the biggest buyer of Malaysian palm oil. It imported 4 million to 5 million tons a year. Most of its was used for cooking oil. China is now a major buyer. Edible oils are a main ingredient in instant noodles. [Source: Hillary Rosner, National Geographic, December 2018]

World’s Top Importers of Palm Oil (2020): 1) India: 7203188 tonnes; 2) China: 6461455 tonnes; 3) Pakistan: 3084363 tonnes; 4) Netherlands: 2526023 tonnes; 5) Spain: 1952094 tonnes; 6) Italy: 1676514 tonnes; 7) United States: 1431786 tonnes; 8) Bangladesh: 1335282 tonnes; 9) Nigeria: 1224500 tonnes; 10) Kenya: 1142638 tonnes; 11) Egypt: 1045176 tonnes; 12) Russia: 1024921 tonnes; 13) Malaysia: 916800 tonnes; 14) Myanmar: 900019 tonnes; 15) Turkey: 805496 tonnes; 16) Japan: 761175 tonnes; 17) Germany: 723513 tonnes; 18) Vietnam: 682129 tonnes; 19) Belgium: 637755 tonnes; 20) South Korea: 587126 tonnes ; [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Palm Oil (2020): 1) India: US$5119263,000; 2) China: US$4123222,000; 3) Pakistan: US$2109310,000; 4) Netherlands: US$1782869,000; 5) Nigeria: US$1530000,000; 6) Spain: US$1395987,000; 7) Italy: US$1244299,000; 8) United States: US$1091722,000; 9) Bangladesh: US$1002405,000; 10) Kenya: US$829605,000; 11) Russia: US$793220,000; 12) Egypt: US$732477,000; 13) Vietnam: US$694738,000; 14) Malaysia: US$665713,000; 15) Myanmar: US$645251,000; 16) Germany: US$603656,000; 17) Japan: US$547942,000; 18) Turkey: US$527266,000; 19) Belgium: US$489871,000; 20) South Korea: US$404405,000

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com ; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated April 2022