TROPICAL FORESTS RECOVER CAN QUICKLY IN DEFORESTED AREAS

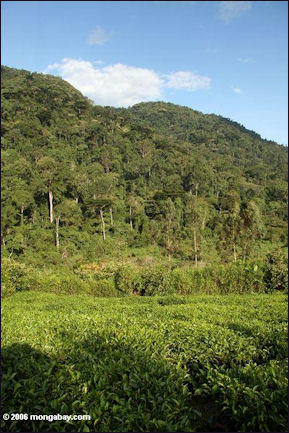

tea plantation in Uganda A group of professors wrote in The Conversation: In a study published in the journal Science, our group pioneers an approach to forest recovery that provides insights from over 2,200 forest plots in naturally regrowing tropical forests across the American and West African tropics. Our research shows that tropical forests recover surprisingly quickly: They can regrow on abandoned lands and recover many of their old-growth features, such as soil health, tree attributes and ecosystem functions, in as little as 10 to 20 years. However, to support effective forest restoration and planning, it is important to understand how quickly different forest functions and attributes recover.[Source: Robin Chazdon, Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Catarina Conte Jakovac, Associate professor of Plant Science, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Lourens Poorter, Professor of Functional Ecology, Wageningen University, The Conversation, and Bruno Hérault, Tropical Forest Scientist, Forests & Societies Research Unit, Cirad, The Conversation December 10, 2021]

“Now, across the world’s tropical regions, forests are regrowing on approximately 3 million square miles (8 million square kilometers) of former farm and ranch land. Forest recovery takes time and often has unpredictable outcomes and variable pathways. Recovery patterns differ between wet and dry tropical forests. Our study focused on 12 attributes that are essential components of healthy forests. They include soil, ecosystem functioning, forest structure and diversity and composition of tree species:

“To assess long-term recovery rates, we compared attributes across forests growing on farmlands that had been abandoned at different times and compared regrowing forests with neighboring old-growth forests. We developed a new modeling approach to estimate how quickly each attribute recovered. Many of these attributes depend on one another. For example, if trees regrow quickly they may produce a lot of leaf litter, which will restore levels of organic carbon in the soil when it decomposes. We analyzed these connections by comparing how strongly forest attributes were associated with one another.

“The forests we studied were in areas of low- to moderate-intensity land use, meaning that soils were not exhausted or eroded and quickly supported regrowing native vegetation. For example, in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest region, 10,425 square miles (2.7 million hectares) of forest regrew naturally from 1996 to 2015. There is much less potential for tropical forests to recover in areas where soils are heavily overworked and no neighboring forests remain.

All of the forest attributes that we examined recovered within 120 years of regrowth. Some recovered 100 percent of their old-growth values in the first 20 years of regrowth. For example, the soil attributes that we analyzed reached 90 percent of old-growth values within 10 years and 98 percent to 100 percent within 20 years. In other words, after 20 years of regrowth, soils in the forests contained virtually as much organic carbon and had similar bulk density as soils in old-growth forests. This quick recovery reflects the fact that the soils at our study sites had not been heavily degraded when forest regrowth started. Ecosystem function attributes also bounced back quickly, with 82 percent to 100 percent recovery within 20 years.

“Forest structure attributes, such as maximum tree diameter, recovered more slowly. On average they reached 96 percent of old-growth values after 80 years of regrowth. Tree species composition and above-ground biomass recovered after 120 years. We identified a set of three attributes — maximum tree size, overall variation in tree size and the number of tree species in a forest — that, viewed together, provide a reliable snapshot of how well a forest is recovering. These three indicators are relatively easy to measure, and managers can use them to monitor forest restoration. It is now possible to monitor tree size and forest structure over large areas and time scales using data collected by satellites and drones.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION: RATES, RESULTS AND ALARM factsanddetails.com ;

CAUSES OF RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

AMAZON DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

DROUGHT AND FIRE: IS THE AMAZON DRYING OUT? factsanddetails.com ;

SLASH-AND-BURN AGRICULTURE (SWIDDEN) factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LUMBER AND TIMBER AND PAPER COMPANIES factsanddetails.com ;

RUBBER: PRODUCERS, TAPPERS AND THE RAIN FOREST factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL: USES, HISTORY, AGRICULTURE AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL BUSINESS: PRODUCERS, COMPANIES, IMPORTERS factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL AND RAIN FOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

COMBATING DEFORESTATION AND EFFORTS TO SAVE THE RAINFOREST factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Rainforest Action Network ran.org ; Rainforest Foundation rainforestfoundation.org ; World Rainforest Movement wrm.org.uy ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Forest Peoples Programme forestpeoples.org ; Rainforest Alliance rainforest-alliance.org ; Nature Conservancy nature.org/rainforests ; National Geographic environment.nationalgeographic.com/environment/habitats/rainforest-profile ; Rainforest Photos rain-tree.com ; Rainforest Animals: Rainforest Animals rainforestanimals.net ; Mongabay.com mongabay.com ; Plants plants.usda.gov

Letting Forests Regrow Naturally — Effective, Low-Cost Way to Slow Climate Change

edge of deforested land in the Amazon A group of professors wrote in The Conversation:“Many organizations and communities are working to restore native forests by reclaiming unproductive or abandoned land and carrying out costly tree-planting efforts. These efforts are designed to encourage the return of native plants and animals and to recover the ecological functions and goods that those forests once provided. But in many cases forests can recover naturally, with little or no human assistance. [Source: Robin Chazdon, Professor Emerita of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, Catarina Conte Jakovac, Associate professor of Plant Science, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Lourens Poorter, Professor of Functional Ecology, Wageningen University, The Conversation, and Bruno Hérault, Tropical Forest Scientist, Forests & Societies Research Unit, Cirad, The Conversation December 10, 2021]

“Most forests around the world today have regrown after human and natural disturbances, including fires, floods, logging and clearance for agriculture. For example, forests recovered in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries and in the eastern U.S. from the early to mid-20th century. Today the northeastern U.S. has more forest cover than it did 100 to 200 years ago.

Scientists and policymakers widely agree that it is critical to protect these regrowing forests and prevent more destruction and conversion of old-growth forests. Our findings show that tropical forest regrowth is an effective and low-cost, nature-based strategy for promoting sustainable development, restoring ecosystems, slowing climate change and protecting biodiversity. And since regrown forests in areas where the land has not been heavily damaged quickly recover many of their key attributes, forest recovery doesn’t always require planting trees. In our view, a range of suitable reforestation methods can be implemented, depending on local site conditions and local people’s needs. We recommend relying on natural regrowth wherever and whenever possible, and using active restoration planting when needed.

Forests the Size of France Regrown Between 2000 and 2020, Study Suggests

An area of forest the size of France has regrown naturally across the world in the last 20 years, a study suggests. The BBC reported: “A team led by WWF used satellite data to build a map of regenerated forests. The restored forests have the potential to soak up the equivalent of 5.9 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon dioxide — more than the annual emissions of the US, according to conservation groups. [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC, May 11, 2021]

Forest regeneration involves restoring natural woodland through little or no intervention. This ranges from doing nothing at all to planting native trees, fencing off livestock or removing invasive plants. William Baldwin-Cantello of WWF said natural forest regeneration is often "cheaper, richer in carbon and better for biodiversity than actively planted forests".

“But he said regeneration cannot be taken for granted — "to avoid dangerous climate change we must both halt deforestation and restore natural forests". "Deforestation still claims millions of hectares every year, vastly more than is regenerated," Mr Baldwin-Cantello said. "To realise the potential of forests as a climate solution, we need support for regeneration in climate delivery plans and must tackle the drivers of deforestation, which in the UK means strong domestic laws to prevent our food causing deforestation overseas."

The Atlantic Forest in Brazil gives reason for hope, the study said, with an area roughly the size of the Netherlands having regrown since 2000. In the boreal forests of northern Mongolia, 1.2 million hectares of forest have regenerated in the last 20 years, while other regeneration hotspots include central Africa and the boreal forests of Canada. But the researchers warned that forests across the world face "significant threats". Despite "encouraging signs" with forests along Brazil's Atlantic coast, deforestation is such that the forested area needs to more than double to reach the minimal threshold for conservation, they said. The project is a joint venture between WWF, BirdLife International and WCS, who are calling on other experts to help validate and refine their map, which they regard as "an exploratory effort".

New Jungles Growing Faster than Rainforests are Being Destroyed

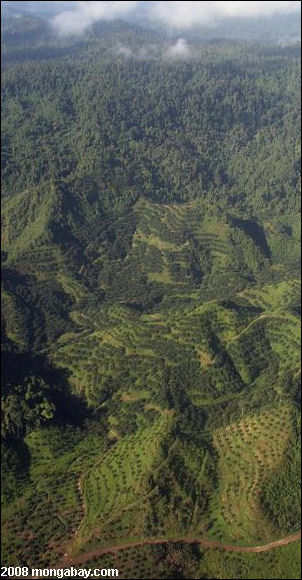

palm oil plantation

in Borneo Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times, “New ‘secondary’ forests are emerging in Latin America, Asia and other tropical regions at such a fast pace that the trend has set off a serious debate about whether saving primeval rain forest — an iconic environmental cause — may be less urgent than once thought. By one estimate, for every acre of rain forest cut down each year, more than 50 acres of new forest are growing in the tropics on land that was once farmed, logged or ravaged by natural disaster. [Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, January 29, 2009]

About 38 million acres of original rain forest are being cut down every year, but in 2005, according to the most recent “State of the World’s Forests Report” by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, there were an estimated 2.1 billion acres of potential replacement forest growing in the tropics — an area almost as large as the United States. The new forest included secondary forest on former farmland and so-called degraded forest, land that has been partly logged or destroyed by natural disasters like fires and then left to nature. In Panama by the 1990s, the last decade for which data is available, the rain forest is being destroyed at a rate of 1.3 percent each year. The area of secondary forest is increasing by more than 4 percent yearly, estimates Joe Wright, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

With the heat and rainfall in tropical Panama, new growth is remarkably fast. Within 15 years, abandoned land can contain trees more than 100 feet high. Within 20, a thick rain-forest canopy forms again. Here in the lush, misty hills, it is easy to see rain-forest destruction as part of a centuries-old cycle of human civilization and wilderness, in which each in turn is cleared and replaced by the other. The Mayans first cleared lands here that are now dense forest. The area around Gamboa, cleared when the Panama Canal was built, now looks to the untrained eye like the wildest of jungles.

Value of New Jungles

Reporting from Chilibre, Panama, Elisabeth Rosenthalwrote in the New York Times, “The land where Marta Ortega de Wing raised hundreds of pigs until 10 years ago is being overtaken by galloping jungle — palms, lizards and ants. Instead of farming, she now shops at the supermarket and her grown children and grandchildren live in places like Panama City and New York. Here, and in other tropical countries around the world, small holdings like Ms. Ortega de Wing’s — and much larger swaths of farmland — are reverting to nature, as people abandon their land and move to the cities in search of better livings.[Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, January 29, 2009]

“There is far more forest here than there was 30 years ago,” said Ms. Ortega de Wing, 64, who remembers fields of mango trees and banana plants. The new forests, the scientists argue, could blunt the effects of rain forest destruction by absorbing carbon dioxide, the leading heat-trapping gas linked to global warming, one crucial role that rain forests play. They could also, to a lesser extent, provide habitat for endangered species.

The idea has stirred outrage among environmentalists who believe that vigorous efforts to protect native rain forest should remain a top priority. But the notion has gained currency in mainstream organizations like the Smithsonian Institution and the United Nations, which in 2005 concluded that new forests were “increasing dramatically” and “undervalued” for their environmental benefits. The United Nations is undertaking the first global catalog of the new forests, which vary greatly in their stage of growth.

“Biologists were ignoring these huge population trends and acting as if only original forest has conservation value, and that’s just wrong,” Wright told the New York Times. He set off a firestorm two years ago by suggesting that the new forests could substantially compensate for rain forest destruction. “Is this a real rain forest?” Dr. Wright asked, walking the land of a former American cacao plantation that was abandoned about 50 years ago, and pointing to fig trees and vast webs of community spiders and howler monkeys.

“A botanist can look at the trees here and know this is regrowth,” he said. “But the temperature and humidity are right. Look at the number of birds! It works. This is a suitable habitat.” Dr. Wright and others say the overzealous protection of rain forests not only prevents poor local people from profiting from the rain forests on their land but also robs financing and attention from other approaches to fighting global warming, like eliminating coal plants.

New Jungles Prompt a Debate on Rain Forests

Where the rain forest meets the sea in Costa Rica

Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times, “But other scientists, including some of Dr. Wright’s closest colleagues, disagree, saying that forceful protection of rain forests is especially important in the face of threats from industrialized farming and logging.The issue has also set off a debate over the true definition of a rain forest. How do old forests compare with new ones in their environmental value? Is every rain forest sacred? “Yes, there are forests growing back, but not all forests are equal,” said Bill Laurance, another senior scientist at the Smithsonian, who has worked extensively in the Amazon. [Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, January 29, 2009]

He scoffed as he viewed Ms. Ortega de Wing’s overgrown land: “This is a caricature of a rain forest!? he said. “There’s no canopy, there’s too much light, there are only a few species. There is a lot of change all around here whittling away at the forest, from highways to development.” While new forests may absorb carbon emissions, he says, they are unlikely to save most endangered rain-forest species, which have no way to reach them.

Everyone, including Dr. Wright, agrees that large-scale rain-forest destruction in the Amazon or Indonesia should be limited or managed. Rain forests are the world’s great carbon sinks, absorbing the emissions that humans send into the atmosphere, and providing havens for biodiversity. At issue is how to tally the costs and benefits of forests, at a time when increasing attention is being paid to global climate management and carbon accounting.

But Dr. Laurance says that is a dangerous lens through which to view the modern world, where the forces that are destroying rain forest operate on a scale previously unknown. Now the rain forest is being felled by “industrial forestry, agriculture, the oil and gas industry — and it’s globalized, where every stick of timber is being cut in Congo is sent to China and one bulldozer does a lot more damage than 1,000 farmers with machetes,” he said.

New Jungles and Biodiversity

Little is known about the new forests — some of them have never even been mapped — and they were not factored into the equation at the meetings. “Our knowledge of these forests is still rather limited,” said Wulf Killmann, director of forestry products and industry at the United Nations agriculture organization. The agency is in the early phases of a global assessment of the scope of secondary forest, which will be ready in 2011. The Smithsonian, hoping to answer such questions, is just starting to study a large plot of newly abandoned farmland in central Panama to learn about the regeneration of forests there. [Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, January 29, 2009]

Elisabeth Rosenthal wrote in the New York Times, “For many biologists, a far bigger concern is whether new forests can support the riot of plant and animal species associated with rain forests. Part of the problem is that abandoned farmland is often distant from native rain forest. How does it help Amazonian species threatened by rain-forest destruction in Brazil if secondary forests grow on the outskirts of Panama City? [Source: Elisabeth Rosenthal, New York Times, January 29, 2009]

Dr. Wright, looking at a new forest, sees possibility. He says new research suggests that 40 to 90 percent of rain-forest species can survive in new forest. Dr. Laurance focuses on what will be missing, ticking off species like jaguars, tapirs and a variety of birds and invertebrates. While he concedes that a regrown forest may absorb some carbon, he insists, “This is not the rich ecosystem of a rain forest.”

Reforestation

Reforestation programs can not return a forest to the diverse state of a primary forest in a short period but it produces forests that provide some of the environmental functions of the original forest and provides commercially exploited wood and other products. In some places reforestation has scored considerable successes but it still lags behind deforestation.

There are different figures out there for deforestation and reforestation rates. By one measure the global reforestation rate between 1990 and 2005 was 2.5 million hectares a year, compared to 7 million to 8 million hectares a year destroyed by deforestation in that period. In the 1990s, in another estimate, 14 millions hectares were lost a year to deforestation but 5.2 million hectares was gained through replanting for a net loss of 9.4 million hectares.

A study published in 2006 in the U.S. journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that many of the world’s forests are making a comeback and some are more thickly forested now than they were 200 years ago. The greatest gains have occurred in China, Ukraine, Spain, Vietnam and the United States while the greatest losses have occurred in Brazil, Indonesia, Nigeria and the Philippines.

The study employed data that measured the density of trees rather than just the area they cover and found that amount of forest increased in 22 of the 50 countries studied. Huge tree planting efforts in China have offset deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia.

palm plantation in Cigudeg, Indonesia

Reforestation Efforts

Reforestation efforts have included attracting profit-motivated businessmen to invest in fast growing teak trees and trees native to the area. Under this scheme the teak trees can be harvest for money while the other tree are allowed to remain growing to rebuild the rainforest.

Planting trees as windbreak between fields also acts as a corridor for animals to move. Tree planting sometimes requires fences to keep livestock from eating the saplings. Peru has had success with reforestation programs in which aid groups set up community nurseries and villagers to decide where the trees should be planted.

The organization Floresta has had some success providing subsistence farmers with loans so they can grow fast-growing wood and fruit trees as cash crops. They grow things like eucalyptus, oregano and vine-growing fruits, increasing their income tenfold from $300 to 3,000. The stumps of eucalyptus resprout to ensure a continual harvest for many years. Soil erosion has almost been eliminated.

According to National Geographic: The United States has pledged to help the world plant and protect a trillion trees by 2030, but the plan has hit a snag: There aren’t enough seedlings to grow into trees for planting — not by a long shot, a new study says. At least three billion tiny trees a year are needed to plant available acres — a 130 percent planting jump that would add tens of billions of dollars in costs for seed collection, infrastructure, and more. The new trees also would need long-term monitoring to ensure they survive pressures such as pests, disease, drought, and fire. Environmentalists say that planting that many trees, and conserving mature ones, is vital to remove planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, helping cool a warming future. [Source: Kyla Mandel, National Geographic June 10, 2021]

Landscape Restoration

Forest landscape restoration is a process which holds great promise globally for combating deforestation, desertification and global warming. It involves replanting of native vegetation and restricting grazing and over use to rejuvenate land to support local agriculture. The new vegetation also reduces flooding by anchoring the region’s soil and acts as a large carbon sink by sucking in carbon dioxide.

Landscape restoration is a slow, complex and painstaking process. Paul Mozur wrote in the New York Times,”It can take decades for vegetation to fully return, and strict attention must be paid to mundane matters like grazing and over-planting.... Because ecosystems vary based on geography, and lasting success depends on the support of local residents, the process is pesteringly cross-disciplinary. Any forest landscape restoration project requires the know-how of engineers, ecologists and soil scientists, plus an understanding of local economics and politics.”

It is becoming harder to deny the importance of forest landscape restoration in combating climate change. A new study by the World Resources Institute shows that about 1 billion hectares of land could be restored across the globe. Rough estimates indicate that carbon sequestration through this process could eliminate 50 percent more carbon from the atmosphere than a proactive cessation of deforestation could.

Efficient Reforestation and Tree Management

One of the simplest ways to remove carbon dioxide from the air is to plant trees. But scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. say the right trees must be planted in the right place if they are to be effective at reducing carbon emissions. Scientists have proposed 10 golden rules for tree-planting, which they say must be a top priority for all nations this decade. [Source: Helen Briggs, BBC, January 26, 2021]

Helen Briggs of the BBC wrote: “A raft of ambitious tree-planting projects are underway around the world to replace the forests being lost. An African-led movement to plant a 5,000-mile (8,048km) forest wall to fight the climate crisis is set to become the largest living structure on Earth, three times the size of the Great Barrier Reef. However, planting trees is highly complex, with no universal easy solution. “If you plant the wrong trees in the wrong place you could be doing more harm than good," said lead researcher Dr Kate Hardwick of RGB Kew.

“All too often natural forests teeming with plants, animals and fungi are replaced by commercial plantations with row upon row of timber trees, which will be harvested after a few decades, she told BBC News. “What we're trying to do is to encourage people, wherever possible, to try and recreate forests which are similar to the natural forests and which provide multiple benefits to people, the environment and to nature as well as capturing carbon." The review of research, published in the journal Global Change Biology, found that in some cases, planned tree planting does not increase carbon capture and can have negative effects.

The 10 golden rules are: 1) “Protect existing forests first: “Keeping forests in their original state is always preferable; undamaged old forests soak up carbon better and are more resilient to fire, storm and droughts. "Whenever there's a choice, we stress that halting deforestation and protecting remaining forests must be a priority," said Prof Alexandre Antonelli, director of science at RGB Kew. 2) Put local people at the heart of tree-planting projects: Studies show that getting local communities on board is key to the success of tree-planting projects. It is often local people who have most to gain from looking after the forest in the future. 3) Maximise biodiversity recovery to meet multiple goals: Reforestation should be about several goals, including guarding against climate change, improving conservation and providing economic and cultural benefits.

“4) Select the right area for reforestation: Plant trees in areas that were historically forested but have become degraded, rather than using other natural habitats such as grasslands or wetlands. 5) Use natural forest regrowth wherever possible: Letting trees grow back naturally can be cheaper and more efficient than planting trees. 6) Select the right tree species that can maximise biodiversity: Where tree planting is needed, picking the right trees is crucial. Scientists advise a mixture of tree species naturally found in the local area, including some rare species and trees of economic importance, but avoiding trees that might become invasive.

7) Make sure the trees are resilient to adapt to a changing climate: Use tree seeds that are suitable for the local climate and how that might change in the future. 8) Plan ahead: Plan how to source seeds or trees, working with local people. 9) Learn by doing: Combine scientific knowledge with local knowledge. Ideally, small-scale trials should take place before planting large numbers of trees. 10) Make it pay: The sustainability of tree re-planting rests on a source of income for all stakeholders, including the poorest.

Mexico’s Vast Tree-Planting Program Often Encourages Deforestation

Max De Haldevang of Bloomberg wrote: In the hills of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula, the jungle abruptly stops and dozens of saplings grow scattered around charred tree stumps. The seedlings are a sign of the government’s vast reforestation program known as Sembrando Vida, or Sowing Life. But so too is the burned out clearing; in this part of Mexico, the project is linked to widespread destruction as well as regeneration. [Source: Max De Haldevang, Bloomberg, March 8, 2021]

“Under Mexico’s previous government, the owner was paid to care for the jungle on their land, but after President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador took office in 2018 that program’s budget was slashed and Sowing Life was introduced. It instead pays farmers to plant trees for fruit or timber on small plots of land, with the aim of creating an industry in deprived rural areas for decades to come. “But a trip in late February to Yucatan and Campeche, two participating states in Mexico’s southeast, showed that flaws at the project’s inception risk undoing its good intentions. “This is what Sowing Life does,” said Jose, a local farmer, kicking a blackened stump.

“Sembrando Vida is Lopez Obrador’s flagship environmental project, a $3.4 billion tree-planting plan intended to help meet climate goals while fulfilling his overarching aim of fighting Mexico’s rampant poverty and inequality. In Yucatan and Campeche, however, locals speak of uncertainty over the legal status of plots and of a dogmatic approach by some program administrators that fails to take into account basic agricultural practices. The principal charge, though, is that the system incentivizes farmers to clear land of jungle in preparation for planting. “In many cases people said, ‘Well, I have my hectare of jungle but the program is coming so I’ll cut down the jungle, use the trees for my house or to sell the wood or whatever, and when the program comes I’ll sow seeds again,’” said Sergio Lopez Mendoza, an ecology and conservation professor at the University of Science and Arts of Chiapas, Mexico’s southernmost state.

“The program is currently paying around 420,000 farmers 4,500 pesos (about $213) a month to plant trees, according to the government. The goal is to reforest a little over one million hectares of degraded land across Mexico and grow more than one billion plants by the end of 2021. The government says it’s on track to meet that target.The previous program paid a lump sum to the community, which would be used to protect and maintain the jungle and ecosystems in their area. Sowing Life provides direct payments, a change that is seen in some areas as harming communal dynamics in favor of individualism.

Before-and-After Satellite Images from Costa Rica Show How the Forest Can Come Back

In 2023 One person on Reddit shared satellite images of Costa Rica, showing how the country’s forests have recovered in the last four decades. Laurelle Stelle wrote in The Cool Down: Like many countries, Costa Rica suffered from severe deforestation. According to Earth.org, the country had lost almost half its forest cover by 1987. Loggers harvested trees for lumber, and farmers took over to grow crops and raise livestock. But the devastating effects of deforestation spurred the Costa Rican government to action, Earth.org reported. A law was passed in 1996, making it illegal to clear forests without a permit, and the government began paying residents to protect the forest instead of cutting it down. [Source: Laurelle Stelle, The Cool Down, August 15, 2023]

The results are clearly visible in the satellite photos shared on r/geography in April. Four gifs show Costa Rica’s various regions, rotating between photos from 1987, 2000, and 2015, according to the original poster. “For all images, the least green is 1987, then 2000, and the most green is 2015,” they said. These gorgeous green forests are one of Costa Rica’s main attractions, Earth.org reported. Every year, the country draws thousands of tourists who come to see the incredible environment. The money from tourism supports 200,000 people and helps pay for the country’s conservation efforts.

Patricia Madrigal-Cordero, former vice-minister for the environment, told Earth.org, “People come to see the mountains, the nature, the forests, and when they are stunned by a monkey or a sloth in the tree, communities realize what they have here, and they realize they should care for it.”

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2024