AMAZON DEFORESTATION

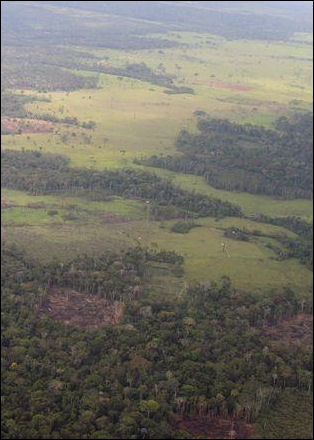

Amazon deforestation The Amazon is the world's largest rainforest and arguably the most closely watched barometer of deforestation. It is about 17 percent deforested, and losses are especially big in Brazil, which lost some 17,000 square kilometers of rainforest in 2020 alone. "If you're looking at the area cleared, Brazil is usually the worst," Nathalie Walker, the director of tropical forest and agriculture at the National Wildlife Federation.Walker, told the Washington Post. And of that, "cattle is the single biggest driver" of loss. [Source: Tik Root and Harry Stevens, Washington Post, November 4, 2021]

Much of the deforested Amazon has been turned into ranchland or farms. The summer dry-season is when the Amazon rainforest gets cut and burned. The smoke this causes can easily be seen from space. Paulo Adario, the Amazon campaign director for Greenpeace in Brazil, told the New York Times, Brazil’s economic choices have driven much of the deforestation in the Amazon, he said. In the late 1960s and the 1970s, the military government encouraged landless families to settle in the region. Road-building, land speculators and ranchers followed, and the forests fell at a quickening pace.

Reuters reported: “The Brazilian Amazon has been under intense pressure in recent decades, as an agricultural boom has driven farmers and land speculators to torch plots of land for soybeans, beef and other crops. That trend has worsened since 2019, when right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro took office and began weakening environmental enforcement.But the Amazon also represents the best hope for preserving what rainforest remains. The Amazon and its neighbors — the Orinoco and the Andean rainforest — account for 73.5 percent of tropical forests still intact. “Brazil must take care of the forest," said Ane Alencar, a geographer with the Amazon Environmental Research Institute who was not involved in the work. "Brazil has the biggest chunk of tropical forest in the world and is also losing the most." [Source: Jake Spring, Reuters, March 8, 2021]

Brazil’s economy is centered on the export of agricultural products, like soybeans and beef, and commodities like iron ore. “The Brazilian model is to be the food supplier to the world and a big supplier of ethanol,” Adario told the New York Times. “The economy will continue to move in the same basic direction. There is no magic in Brazil.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION: RATES, RESULTS AND ALARM factsanddetails.com ;

CAUSES OF RAINFOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

DROUGHT AND FIRE: IS THE AMAZON DRYING OUT? factsanddetails.com ;

SLASH-AND-BURN AGRICULTURE (SWIDDEN) factsanddetails.com ;

RAINFOREST LUMBER AND TIMBER AND PAPER COMPANIES factsanddetails.com ;

RUBBER: PRODUCERS, TAPPERS AND THE RAIN FOREST factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL: USES, HISTORY, AGRICULTURE AND PRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL BUSINESS: PRODUCERS, COMPANIES, IMPORTERS factsanddetails.com ;

PALM OIL AND RAIN FOREST DEFORESTATION factsanddetails.com ;

COMBATING DEFORESTATION AND EFFORTS TO SAVE THE RAINFOREST factsanddetails.com ;

NEW JUNGLES AND REFORESTATION factsanddetails.com

Deforestation Wiped out 8 Percent of Amazon Between 2000 and 2018: Study

Amazon burning The the Amazon lost 513,016 square kilometers (198,077 square miles) — an area larger than Spain and 8 percent of the Amazon forest — due to deforestation between 2000 and 2018, according to a study by the Amazon Geo-Referenced Socio-Environmental Information Network (RAISG), a consortium of groups from across the region.[Source: Paula Ramon, AFP, December 9, 2020]

AFP reported: “The consortium found that after making gains against deforestation early in the century, the Amazon region has again slipped into a worrying cycle of destruction. “Deforestation has accelerated since 2012. The annual area lost tripled from 2015 to 2018," the study found. “In 2018 alone, 31,269 square kilometers of forest were destroyed across the Amazon region, the worst annual deforestation since 2003."

“The destruction is fueled by logging, farming, ranching, mining and infrastructure projects on formerly pristine forest land. “The statistics presented by RAISG are an alarm bell on the increasing pressures and threats facing the region," said researcher Julia Jacomini of the Socioenvironmental Institute (ISA), a Brazilian environmental group that is part of RAISG.

“The destruction in Brazil has only accelerated since far-right President Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019. Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon surged to a 12-year high of 11,088 square kilometers from August 2019 to July 2020, according to government figures. That was a 9.5-percent increase from the previous year, when deforestation also hit a more than decade-long high.

“Bolsonaro has come under fire from environmentalists and the international community for cutting funding for rainforest protection programs and pushing to open protected lands to agribusiness and mining. He has presided over a surge in wildfires in the Brazilian Amazon since taking office. “Deforestation is also surging in Bolivia and Colombia, RAISG found. Bolivia lost 27 percent of its Amazon forest cover to fires from 2000 to 2018, it said.

Cattle Ranching and Amazon Deforestation

Greenpeace contends that the cattle industry in the Amazon is the biggest driver of global deforestation. Mato Grosso is the the Brazilian state with the highest rate of deforestation in the Amazon and the country’s largest cattle herd. Soil erosion often follows rapid and haphazard agricultural and livestock expansion, especially for cattle ranches and dairy farms. Stephen Eisenhammer of Reuters wrote: Land stripped of native vegetation, especially when transformed into pasture and pounded hard by grazing cattle, loses ability to retain water in soil and foliage. Rain runs off the altered surface in sudden surges, dragging topsoil into streams and rivers that then clog and dry. [Source: Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters, October 23, 2021]

cattle pastures In June 2009 Greenpeace released a report called “slaughtering the Amazon,” which detailed the link between forest destruction and the expansion of cattle ranching in the Amazon. The report led some multinational companies, including shoe manufacturers like Adidas, Nike and Timberland, to pledge to cancel contracts unless they received guarantees that their products were not associated with cattle or slave labor in the Amazon. Beef customers like McDonald’s and Wal-Mart also pressed producers to change their practices in the Amazon, Mr. Furtado said.

Alexei Barrionuevo wrote in the New York Times, “Here in Mato Grasso, 700 square miles of rain forest was stripped in the last five months of 2007 alone, according to Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, which tracks vanishing forests. “With so much money to be made, there are no laws that will keep forest standing,”John Carter, a rancher who settled here 15 years ago, told the New York Times as he flew his Cessna over the denuded land one day this summer.

Settlers and Amazon Deforestation

The Amazon is home to communities who say they need to use the forest for mining and commercial farming in order to make a living. At the same time, indigenous communities want the mining and farming to stop to protect the rainforest and their ways of life. [Source: BBC]

Until very recently, developing the Amazon was the priority, and some settlers feel betrayed by the new stigma surrounding deforestation. Much as in the 19th-century American West, the Brazilian government encouraged settlement through homesteaders’ benefits like cheap land and housing subsidies, many of which still exist today.

“It was revolting and sad when the world said that deforestation was bad — we were told to come here and that we had to tear it down,” said Mato Grosso’s secretary of agriculture, Neldo Egon Weirich, 56, who moved here in 1978 and noted that to be eligible for loans to buy tractors and seed, a farmer had to clear 80 percent of his land. He is proud to have turned Mato Grosso from a malarial zone into an agricultural powerhouse. “Mato Grosso is under a microscope — we know we have to do something,” Mr. Weirich said. “But we can’t just stop production.”

Even today, settlers around the globe are buying or claiming cheap “useless” forest and transforming it into farmland. Clearing away the trees is often the best way to declare and ensure ownership. Land that Mr. Carter has intentionally left forested for its environmental benefit has been intermittently overtaken by squatters — a common problem here. In parts of Southeast Asia, early experiments in paying landowners for preserving forest have been hampered because it is often unclear who owns, or controls, property.

Amazon Deforestation in the 1980s

Development projects and domestic migration during the 1970s and 1980s led to deforestation of 414,400 square kilometers (160,000 square miles), or 8.5 percent of the Brazilian Amazon forest. Much of the forest was burned to provide land for homesteaders and cattle ranchers. This burning released large amounts of carbon dioxide. The forest was also degraded by mining and hydroelectric projects.

By the end of the 1980s, the trend was reversing. The pace of deforestation was reduced by half in the late 1980s and early 1990s as a result of government initiatives to protect the environment, including new legislation, the revision of tax incentives, and an emergency program carried out since 1989 during the dry season to counter illegal clearing and burning. The rate of deforestation is monitored by remote sensing satellites.

The most destructive deforestation in Brazil in the 1980s took place in Rondônia, a Mississippi-size state in the western part of the country near the Bolivian border. The population of Rondônia doubled in the 1980s when the trans Amazon BR-364 highway was paved, and settlers were offered 125 acre parcels of free land.

The population of Rondônia leapt from 110,000 in 1970 to 1.4 million in 1995. Satellite photographs of Amazon form that time of undeveloped areas show an undisturbed blanket of green broken only by blue rivers and lakes. Along the 364 in Rondônia, the land is scarred by settlements that appear as long strips of cleared land along the secondary roads.

For a while 150,000 new settlers arrived each year in Rondônia, increasing the state’s population by 15 percent in a few years. Pôrto Velho, the state's capital, went from a frontier outpost into a swollen city of 450,000 in a few decades. Another town grew to 110,000 only 13 years after it was founded. At the height of Rondônia settlement wave it was estimated that 181,300 square kilometers (70,000 square miles) of Amazonian trees and other tropical growth was set afire during the dry season. Nearly 20 percent of the state's rain forests, an area the size of Maryland, was claimed in 20 years. And remember this is just one part of Brazilian Amazonia. [Source: William Ellis, National Geographic, December 1988]

Amazon Deforestation in the 1990s

The World Wildlife Fund estimated that by the year 2000, 12 to 15 percent of the Amazon rain forest has had been deforested and additional 15,000 square kilometers ( 5,800 square miles), an area the size of Connecticut, was lost every years.

Despite the infusion of millions of dollars and international campaigns supporting the rain forest cause, burning of the Amazon increased 28 percent between 1996 and 1997 and deforestation increased 34 percent between 1991 and 1997.

"Deforestation has done nothing but go up," Stephen Scwartzaman of the Environmental Defense Fund told the New York Times. "Where the most money has gone is where the fires have increased." In 1997, half the fires were in Mato Grasso, where the World Bank lent $205 million to a forest management program.

In the 1990s, the Brazilian Amazon states of Mato Grasso and Para were heavily deforested. In Amazonas, around Manaus, 98 percent of the original forest was still intact. At that time farmers were are believed to have caused 40 percent of the deforestation in the Amazon.

Amazon Deforestation in the 2000s

Deforestation in the Amazon was bad in the early 2000s, eased up a bit in the mid 2000s and then starting let bad in the late 2000s, and accelerating in the 2010s. Deforestation hit a high of 49,240 square kilometers (19,100 square miles) of forest loss in 2003 — a record for this century — then eased to a low of 17,674 square kilometers (6,825 square miles) in 2010. When deforestation was reduced, it became common to deforest smaller areas, because the deforesters tried to evade the satellites.“ [Source: Paula Ramon, AFP, December 9, 2020]

The Amazon rain forest was deforested more than twice in 2008 as it was in 2007, Brazilian officials and AP reported, acknowledging a sharp reversal after three years of declines in the deforestation rate. Environment Minister Carlos Minc said coming elections were partly to blame, with mayors in the region turning a blind eye to illegal logging in hopes of gaining votes. Environmentalists blame the global spike in food prices for encouraging soy farmers and cattle ranchers to clear land for crops and grazing. Deforestation increased 228 percent in August compared with the same month a year ago, according to the National Institute for Space Research, which uses satellite images to track logging. [Source: Associated Press, New York Times, September 30, 2008]

Ernesto Londoño of New York Times said: During the 1990s and the early 2000s, we see deforestation reaching really staggering levels. Concern around the world, I think, reaches a point where the Brazilians can no longer ignore what people outside of the country were saying about this. So when President Lula, a leftist, is in office in the early 2000s, he appoints a woman who was from the rainforest to serve as his minister of the environment. Her name is Marina Silva. And she came up with a really bold and ambitious plan to rein in deforestation and create more conservation areas. She was somebody who was lauded across the world for doing something that people thought was almost impossible, to stop these loggers and these miners and these farmers from reaching deeper and deeper into the Amazon year after year after year. And for a while, Brazil was pretty successful. [Source: “The Daily” Hosted by Michael Barbaro, New York Times, August 28, 2019]

Another thing the government did was it started issuing some pretty stiff fines for deforestation and other environmental crimes. And for a while, this had the intended effect. And one of the reasons Brazil was successful in reining in deforestation during this era is the economy was doing pretty well. So there were plenty of jobs in the city. And people were less tempted to venture deep into the jungle, where they faced the risk of fines. However, the good days came to an end. And in 2014, the country plunged into a brutal recession. And what this meant was tens of thousands of men were suddenly unemployed. And many of them were lured back into the jungle. Why? Because there was money to be made. These were dangerous jobs. These were risky ventures. But for many people, it was the only way to put food on the table.

Amazon Deforestation Dramatically Increases Under Bolsonaro

Amazon deforestation increased dramatically when Jair Bolsonaro became the 38th president of Brazil. After he took office in 2019, Amazon deforestation exceeded 10,000 square kilometers (3,861 square miles) every year. Before Bolsonaro became president, the Brazilian Amazon hadn’t recorded a single year with that much deforestation in over a decade and, between 2009 and 2018, the average was 6,500 square kilometers. Para accounted for 39 percent of deforestation from 2020 to 2021, according to Deter data, the most of any Amazonian state. [Source: Débora Álvares, Associated Press, August 13, 2021]

In 2020, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon surged a 12-year high. A total of 11,088 square kilometers (4,281 square miles) of forest was destroyed in Brazil's share of the Amazon in the 12 months to August, according to the Brazilian space agency's PRODES monitoring program, which analyzes satellite images to track deforestation. That is equivalent to an area larger than Jamaica, and was a 9.5-percent increase from the previous year, [Source: AFP, December 1, 2020]

In February 2022, the BBC reported: Deforestation usually slows down in January because the rainy season prevents loggers accessing the forest but the number of trees cut down in the Brazilian Amazon in January 2022 far exceeded deforestation for the same month in 2021 according to government satellite data. In fact the area destroyed was five times larger than 2021, the highest January total since records began in 2015. [Source: Georgina Rannard, BBC, February 12, 2022]

Satellite image of Bolivian Amazon in June 2002“Environmentalists accuse Bolsonaro of allowing deforestation to accelerate. The latest satellite data from Brazil's space agency Inpe again calls into question the Brazilian government's commitment to protecting its huge rainforest, say environmentalists. "The new data yet again exposes how the government's actions contradict its greenwashing campaigns," explains Cristiane Mazzetti of Greenpeace Brazil. “Environmentalists say that they are not surprised by the record January felling, given that President Bolsonaro has significantly weakened legal protections since he took office in 2019. The Brazilian government argues that in the period between August, 2021 and January 2022, overall deforestation was lower compared to the same period a year earlier.

“Deforestation totaled 430 square kilometres (166 square miles) in January, 2022 — an area more than seven times the size of Manhattan, New York. Felling large numbers of trees at the start of the year is unusual because the rainy season usually stops loggers from accessing dense forest. “There are a number of factors driving this level of deforestation. Strong global demand for agricultural commodities such as beef and soya beans is fuelling some of these illegal clearances — Another is the expectation that a new law will soon be passed in Brazil to legitimise and forgive land grabbing.

Bolsonaro's Environmental Policies

Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro is a right-wing, Donald-Trump-like figure. He campaigned as a patriotic man of the people and was elected Brazil's President in October 2018. He survived being stabbed by knife in the abdomen during the campaign and took office in January 2019. He is a strong supporter of agribusiness. The Washington Post reported before he won the presidency that was likely to favor profits over preservation. He "has chafed at foreign pressure to safeguard the Amazon rain forest and he served notice to international nonprofit groups such as the World Wildlife Fund that he will not tolerate their agendas in Brazil. He has also come out strongly against lands reserved for indigenous tribes.” Thais Borges and Sue Branford reported in Mongabay in May 2019 that a “new manifesto by eight of Brazil’s past environment ministers warns that Bolsonaro’s draconian environmental policies, including the weakening of environmental licensing, plus sweeping illegal deforestation amnesties, could cause great economic harm to Brazil”. [Source: Kim Heacox, The Guardian, October 7, 2021]

Bolsonaro has weakened environmental protections for Amazon and argued that the government should exploit the area to reduce poverty. According to to Associated Press: The far-right president has encouraged development of the biome and dismissed global handwringing about its destruction as a plot to hold back the nation’s agribusiness. At the same time, his administration defanged environmental authorities and legislative measures to loosen land protections have advanced, emboldening land grabbers. [Source: Débora Álvares, Associated Press, August 13, 2021]

At the U.S.-led climate summit in April 2021, Bolsonaro shifted his tone on Amazon preservation and exhibited willingness to step up commitment, even though many critics remain doubtful of his credibility. In June 2021, he issued a decree returning soldiers to the Amazon to bolster policing against logging and other illegal land clearance — even as environmental groups allege the mobilization is mostly symbolic, given troops are ill-prepared to conduct oversight. Earlier, Bolsonaro had exalted the need to tap the Amazon’s resources, cast aspersions on environmental activists who defend the rainforest and snarled at European leaders who decried its destruction. He also supported the so-called agribusiness-friendly “land grabbing bill" that would increase the size of public lands that can be made legal for private ownership without in-person surveys from authorities. [Source: David Biller, Associated Press, May 8, 2021]

“At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021, Bolsonaro was one of the world leaders who promised to halt and reverse deforestation by the end of this decade.“ Before that he said Brazil requires outside funds to curb deforestation. U.S. President Joe Bide has directly called on Brazil to take stronger action and has proposed countries provide Brazil with $20 billion to fight deforestation. His presidential administration has since made clear it would only be willing to contribute once Brazil shows concrete progress, and talks have stalled.

Oil Disaster in the Ecuadorian Amazon

Bob Herbert wrote in the New York Times, “For many years, indigenous people from a formerly pristine region of the Amazon rainforest in Ecuador have been trying to get relief from an American company, Texaco (which later merged with Chevron), for what has been described as the largest oil-related environmental catastrophe ever...Texaco operated more than 300 oil wells for the better part of three decades in a vast swath of Ecuador’s northern Amazon region, just south of the border with Colombia. Much of that area has been horribly polluted. The lives and culture of the local inhabitants, who fished in the intricate waterways and cultivated the land as their ancestors had done for generations, have been upended in ways that have led to widespread misery. [Source: Bob Herbert, New York Times, June 4, 2010]

Texaco came barreling into this delicate ancient landscape in the early 1960s with all the subtlety and grace of an invading army. And when it left in 1992, it left behind, according to the lawsuit, widespread toxic contamination that devastated the livelihoods and traditions of the local people, and took a severe toll on their physical well-being.

In a lawsuit filed by the indigenous people of the region against Chevron the plaintiffs said: the oil company deliberately dumped many billions of gallons of waste byproduct from oil drilling directly into the rivers and streams of the rainforest covering an area the size of Rhode Island. It gouged more than 900 unlined waste pits out of the jungle floor — pits which to this day leach toxic waste into soils and groundwater. It burned hundreds of millions of cubic feet of gas and waste oil into the atmosphere, poisoning the air and creating “black rain” which inundated the area during tropical thunderstorms.”

The quest for oil is, by its nature, colossally destructive. And the giant oil companies, when left to their own devices, will treat even the most magnificent of nature’s wonders like a sewer. But the riches to be made are so vastly corrupting that governments refuse to impose the kinds of rigid oversight and safeguards that would mitigate the damage to the environment and its human and animal inhabitants.

Image Source: Mongabay mongabay.com ; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “The Private Life of Plants: A Natural History of Plant Behavior” by David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, 1997); New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Malaysia Tourism Promotion Board, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated November 2024