CLASSIC JAPANESE LITERATURE

Kojiki The written literature of Japan forms one of the richest of Oriental traditions. It has received foreign influences since its beginning in the 8th century. Before the middle of the 19th century, the source of influence was the culture of China. After the middle of the 19th century, the impact of modern Western culture became predominant. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

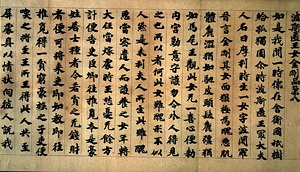

Books in Japan in generally read right to left with the script hanging vertically from the page. The first written language used in Japan was Chinese. Because Chinese characters were often unsuited for certain Japanese sounds, a form of Japanese script called “kana” was developed in the Heian Period (A.D. 794-1185). As the use of kana become more widespread among the aristocracy, it paved the way for the development of unique Japanese literary styles that expressed the feelings and thoughts of the Japanese.

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Literature Home Page www.jlit.net ; History of Japan’s Literature kanzaki.com/jinfo ; Japanese Literatures Resources Page mockingbird.creighton.edu ; National Institute of Japanese Literature nijl.ac.jp ; Collection of Japanese Literature with Genji Translation gutenberg.org ; Japanese Text Initiative etext.lib.virginia.edu ; Asian Rare Books asianrarebooks.net/ ; Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co

Classic Works Japanese Creation Myth Washington State University ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; 100 Poems by 100 Poets /etext.lib.virginia.edu ; Tale of Heike site meijigakuin.ac.jp

Folk Tales Japanese Folk Tale Database isc.senshu-u.ac.jp ; Japanese Myths markun.cs.shinshu-u.ac.jp ; Folk Tales from Japan pitt.edu/~dash ; Old Stories of Japan geocities.co.jp/HeartLand-Gaien

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TALE OF GENJI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BASHO, HAIKU AND JAPANESE POETRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC 20TH CENTURY JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN LITERATURE AND BOOKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HARUKI MURAKAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS AND WESTERN WRITERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Themes in Japanese Literature

Japan has produced many literary "schools." Loyalty, obligation, and self-sacrifice compromised by human emotion and affected by elements of the supernatural are major themes of classic Japanese literature.

“Kisetsukan” (“the feel of the season”) is an important concept in Japanese cultural and artistic traditions. The Japanese often write about the seasons in their correspondence.

The changing seasons is a theme addressed in “The Take of Genji”, an influential 11th century novel. The poems in the “Kokin Wakashu”, an anthology of waka poems compiled in the 10th century, are arranged in the order of the seasons. In haiku, every poem must contain an appropriate “kigo” (‘season word”). There is even a book that lists all recognized kigo by season.

“Monogatari”, a style of literary narrative that concentrates on the life of a single character, was used in the “Tale of Genji” and is still used in television dramas today.

Earliest Japanese Literature

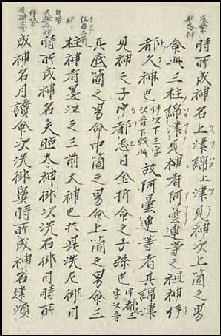

Ancient scoll attributed to

the 8th century emperor Shomu The earliest forms of literature in Japan were most likely myths and stories told by shaman-storytellers. On Kyushu you can still find blind story-tellers who travel from town to town singing tales of feudal lords and samurai.

In early historical times, Chinese classic were dominate form of literature in Japanese courts. Official embassies to the Sui (589--618) and Tang (618--907) dynasties of China (“kenzuishi “and “kentoshi”, respectively), initiated in 600, were the chief means by which Chinese culture, technology, and methods of government were introduced on a comprehensive basis in Japan. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The earliest written records of Japan were the “Kojiki” (The Record of Ancient Matters), written in A.D. 712, with Chinese characters depicting the Japanese language, and the “Nihon Shoki” (Japanese Chronicles), written in A.D. 720, a document that chronicles Japan's history from the birth of the first emperor to A.D. 697. Both documents were modeled after Chinese texts. They presented myths as if they were history, inserted fictitious rulers, and claimed the Japanese had a divine purpose on earth. The “Kojiki “ was written in hybrid Sino-Japanese. The “Nihon shoki “ was written in classical Chinese. They were compiled under the sponsorship of the government for the purpose of authenticating the legitimacy of its polity. A mong these collections of myths, genealogies, legends of folk heroes, and historical records, there appear a number of songs — largely irregular in meter and written with Chinese characters representing Japanese words or syllables — that offer insight into the nature of preliterate Japanese verse.

Emperor Saga (A.D. 786-842) created anthologies of Chinese poetry. Japanese literature, including waka poetry, gradually entered the cultural mainstream during the reign of Emperor Uda (867-931). “Taketori Monogatari” (“The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter”) was written around 811 and is regarded as Japan's first novel. It included poems written by emperors, empresses, courtiers and ordinary people.

A revolutionary achievement of the mid- 9th century was the development of a native orthography (“kana”) for the phonetic representation of Japanese. Employing radically abbreviated Chinese characters to denote Japanese sounds, the system contributed to a deepening consciousness of a native literary tradition distinct from that of China. The introduction of “kana “also led to the development of a prose literature in the vernacular, early examples of which are the a collection of vignettes centered on poems; and the diary “Tosa nikki “(935; “The Tosa Diary”). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Tale of Genji

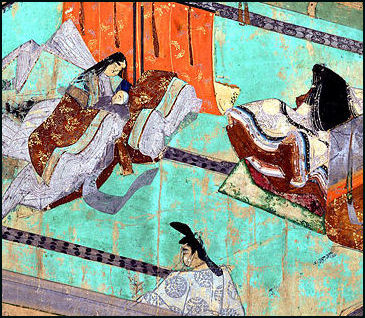

“Tale of Genji” is Japan's most famous classical literary work. Regarded by some scholars as the world's first important novel and the first psychological novel, it was written as an epic poem by Murasaki Shikibu (975-1014), a lady from the Japan Imperial court, between A.D. 1008-20.

As a literary treasure “Tale of Genji” is to the Japanese what “The Odyssey” and “The Iliad” are to the West. It is written in episodes as if serialized in a magazine. It was written mostly in hiragana (kana) as women at the time were not supposed to learn kanji (Chinese characters).

“The Tale of Genji” is the story of handsome Prince Hikaru Genji. The first half deals the life of Genji. The second half deals with period after Genji's death especially in regard to the tragedies of his son, his grandson and three daughters of a ruined businessman. Genji means the "shining one.”

The “Tale of Genji” story features an expressive narrative and a diverse cast of characters and is filled with details about court life in the mid Heian period and aesthetic pursuits that are still alive today: waka poetry, gakaku court music, noh and the tea ceremony.

Although there is no historical documentation that indicates when Murasaki Shikibu began or completed the “Tale of Genji”, her diary indicates that she at least completed the tale’s fifth Wakamurasaki chapter on November 1st 2008 while staying at Ishiyamadera temple in Otsu, not far from Kyoto. The 1000th anniversary of the novel in 2008 was celebrated with a special ceremony in Kyoto attended by the Emperor and Empress in which November 1st was declared Classics day.

It is said that during her stay at Ishiyamadera temple Murasaki she saw a full moon rise over Lake Biwa and got the idea for the Suma chapter in which Genji remembers his glory days in Kyoto while looking a full moon from a beach in Suma, currently in Hyogo Prefecture, to which he had been banished because of a scandalous romantic liaison.

Poetry, See Separate Article

Medieval Japanese Literature

Most of the early influential works of literature were by women. One reason for this is that men spent their time studying classic Chinese literature and wrote in archaic, classical-style Chinese while women enjoyed life and wrote in the vernacular. “Makura no Soshi” “(Pillow Book”) is a brilliant series of poems that provide an “exquisitely detailed and refined record of court life” written by another talented court lady, Sei Shinagon Shonagon. One of the poems goes: "A good lover will behave just as elegantly at dawn as at any other time. He tells her how he dreads the coming day, which will keep them apart. Then almost imperceptibly he glides away."

A major development in prose literature of the medieval era was the war tale (“gunki monogatari”). Examples of this lterary form include “Heike Mongatari” (“Tale of Heike”), a historical samurai romance story about the Heike clan and their tragic downfall written in 1223 and “Taiheiki” (“Record of the Great Peace”), which appeared in mid 1300s. Sometimes referred to as the Japanese Iliad, the “Heike Monogatari “ relates the events of the war between the Taira and Minamoto families that finally brought an end to imperial rule; it was disseminated among all levels of society by itinerant priests who chanted the story to the accompaniment of a lutelike instrument, the “biwa”.

“The social upheaval of the early years of the era led to the appearance of works deeply influenced by the Buddhist notion of the inconstancy of worldly affairs (“mujo”). The theme of “mujo “provides the ground note of “Heike monogatari “and the essay collections “Hojoki “(1212; “The Ten Foot Square Hut”), by Kamo no Chomei, and “Tsurezuregusa “(ca 1330; “Essays in Idleness”), by Yoshida Kenko.

Edo Period Literature

Chikamatsu Monzaemon The formation of a stable central government in Edo (now Tokyo), after some 100 years of turmoil, and the growth of a market economy based on the widespread use of a standardized currency led to the development in the Edo period (1600 — 1868) of a class of wealthy townsmen. General prosperity contributed to an increase in literacy, and literary works became marketable commodities, giving rise to a publishing industry. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Humorous fictional studies of contemporary society such as “Koshoku ichidai otoko “(1682; “The Life of an Amorous Man”), by Ihara Saikaku, were huge commercial successes, and prose works, often elaborately illustrated, that were directed toward a mass audience became a staple of Edo-period literature. Commercial playhouses were established for the performance of puppet plays (“joruri”) and “kabuki”, whose plots often centered on conflicts arising from the rigidly hierarchical social order that was instituted by the Tokugawa shogunate.

“The 17-syllable form of light verse known as “haikai “(later known as “haiku”), whose subject matter was drawn from nature and the lives of ordinary people, was raised to the level of great poetry by Matsuo Basho. He is especially well known for his travel diaries, such as the “Oku no hosomichi “(1694; “The Narrow Road to the Deep North”). A number of philologists, among them Keichu, Kamo no Mabuchi, and Motoori Norinaga, wrote scholarly studies on early literary texts, such as “Kojiki”, “Man — yoshu”, and “The Tale of Genji”.

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) was a dramatist who wrote many famous bunraku puppet and kabuki theater pieces.

Japanese Folk Tales

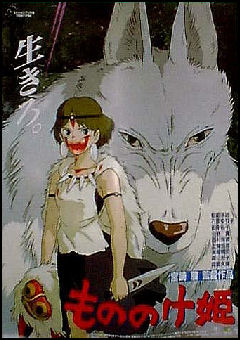

The “Princess Monoke”, on which the famous anime film was based, dates to the 15th and 16th century. Set in 14th century Japan, it is about girl, known both as Princess Mononoke and San, who is raised by elephant-size wolves and polka-dotted wild boars, and Ashitaka, a young boy who receives a curse from a demon boar and seeks out the Great Deer God of the Forest, who can lift the curse. During his quest for the god Ashitaka runs into San.

In one famous folk story about revenge a monkey injures a crab by throwing a persimmon at it with the crab getting even ten time over with the monkey being burned by chestnuts, stung by a bee, pinched repeatedly by a group of crabs, pieced by a needle and struck on the head by a mortar. There is a similar story about a racoon who kills a woman and rabbit who loved the woman who takes out his revenge by setting the racoon on fire. applying red pepper to his burns and finally drowning him.

There are many stories about mythical creatures and supernatural beings. The “kappa” is an amphibious, web-footed aquatic creature, about the size of an 11-year-old boy, with a sharp beak for a mouth and bald patches on the tops of it head. Kappas are known for tripping up horses and stealing vegetables from fields, and using their anus to cause various forms of mischief. Children are told not to swim too far out in rivers or the kappa will pull them under and suck the life energy out of them. Kappas receive their power from a depression in their head that holds water. The easiest way to trip one up is to bow. When the kappa returns the bow, water spills from its head and it loses its powers.

Tanukis appear more often in Japanese legends and fairy tales than almost any other real animal. Known as tricksters who play practical jokes and set traps, especially if it helps them get some food, they crashing parties, drink up sake and then paying with dry leaves instead of real money. Many stories revolve around battles of wits between tanukis and farmers or are fantastic tales with tanukis changing into monsters or beautiful women.

See Religion, Foxes, Spirits, Yokai

Itachi Weasels and Japanese Folklore

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: Like many Japanese animals, the itachi appears in various avatars. In addition to the simple living creature that hunts along the ditches, there are several superpowered yokai versions, known as Kama-itachi, or "sickle weasels." The tip of each Kama-itachi limb is fitted with a razor-sharp sickle, and the creatures move about in whirlwinds too fast to follow with the naked eye. [Source: Kevin Short, April 5, 2012]

Kama-itachi have been reported in various regions of Japan. Whenever people working outside find small, previously unnoticed cuts on their bare skin, they attribute it to a Kama-itachi. These stories are especially popular in the colder regions, and some researchers think that the idea of a Kama-itachi may have developed from small cuts that can easily form in skin that has been heavily chapped by the wind and cold.

“In some regions, the Kama-itachi is believed to be actually three weasels working together. The first one prepares the skin surface, the second delivers the cut, and the third rubs on some herbal medicine that seals the wound. All this happens in a blink of an eye!

Sometimes the Kama-itachi is said to be an izuna, which is actually the name of a different species of mustelid, the least weasel (M. nivalis). This is the smallest of all the mustelids, but enjoys a wide distribution from the arctic through the cool temperate zones clear across both the North American and Eurasian continents. Here in Japan, the izuna is found on Hokkaido and the northern tip of Honshu. In these cases, however, one must keep in mind that Japanese common names for animals vary widely from region to region, and the term izuna may also refer to the Japanese weasel as well.

“Another belief regarding weasels, prevalent in mountain villages, is that women in certain households have under their control a number of miniature weasel spirits, which can be used for fortune-telling or prophesies, or sent on magical errands across the countryside to do their mistress's bidding. These families, called izuna-tsukai, are traditionally feared and segregated against. In some regions, the animal spirits under their control may be instead dogs, foxes or snakes. The magical rites and spells for controlling the spirits are passed down from woman to woman.

“Kama-itachi no Yoru, or "Night of the Kama-itachi," is the title of a long-selling computer game in which characters trapped in a hotel must solve the mystery of a serial killer in their midst. There is also a popular owarai-konbi, a comedian duo, called Kama-itachi.

Japanese Ghost Stories

Ghost stories are associated with the summer time, especially around the Bon Festival when Japanese pay their respects to their ancestors. They are often featured in the stories told by rakugo comic storytellers and depicted in silk paintings. During the Edo period there was a ban on the telling of ghost stories even though ghosts were reproduced through woodblock printing and widely sold as cards.

Many ghost stories revolve around ghosts who have to return to the world of the living to take care of some unfinished business or seek the repayment of a moral debt. The Japanese concept of “on”, loosely translated as obligation, lies at the heart of many ghost stories. Unfulfilled on is an unnerving thing if it involves someone who is dead.

In his book on ghosts Japanologist Lafcadio Hearns wrote about a stone turtle at Gesshoji temple in Matsue that came to life at night and devoured people and female a ghost at Daioji temple in the same town that gave birth to a baby in a grave and then went out to buy candy for it.

Famous Japanese Ghost Stories

One favorite ghost story “Bancho Sarayashiki” is about a maid named Okiku who is employed by an evil samurai to take care of ten precious plates, She is told no matter what to never let anything happen to the plates. One day one of the plates is broken or stolen — there are many variations of the story — and Okiku is blamed and killed and thrown down a well by the samurai. Okiku’s soul can no rest, being killed so unjustly, and her spirit returns to Earth as a ghost , repeatedly counting the plates and coming up with one missing.

A famous ghost story called “Botandoro” (“The Peony Lantern”) is about a man and women involved in love affair. The man becomes ill and is unable to ses his lover. When he recovers and visits her he finds that she has died. The lover’s ghost visits him and eventually he dies embracing her skeleton.

“No Mononoke Roku” (“Ino Ghost Story”) is about a 16-year-old youth named Ino Heitrai who saw ghosts — including a giant one-eyed man, a woman with her head on upside down, an earthworm ghost and monstrous frog — every night for 30 days. The story was made into a popular anime called “Asagiri no Miko” (“Shrine Maiden in the Morning Mist”).

Book: “Ghosts and the Japanese Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends” by Michiko Iwasaka and Barre Toelken

Tale of the 47 Loyal Assassins

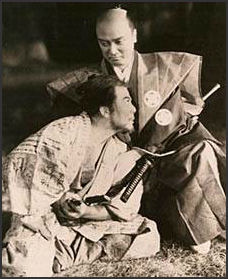

Film version of

47 Loyal Assassins One of the most famous events in Japanese history was the mass suicide of 47 samurai in 1702. Known as the “Tale of the 47 Loyal Assassin” or “Churshingura”, it has been the subject of many “kabuki” dramas, “bunkara” puppet theaters, children's books, bestselling novels, movies and television mini-series and documentaries.

The series of events that led to the mass suicide began when Kira Kozukenosuke, an evil warlord and senior official in the Tokugawa shogunate, picked a fight with a daimyo named Asano, who grazed the forehead of Kira with his sword in a fit of anger in a corridor of Edo castle. Such an act was strictly forbidden in the castle and Asano was forced to commit suicide or be killed by Kira's men, depending on the version of the story. Knowing the Asano's death would probably be avenged Kira fortified the walls of his castle and tripled the number of men protecting it.

Forty-seven samurai loyal to Asano vowed to get revenge but they waited for two years and acted like drunken fools, ignoring their wives and children and even failing to show up for the burial of Asano, during that time to make Kira think they were too consumed in drowning their sorrows to be concerned with revenge.

On December 14, 1702, the 47 samurai broke into Kira's Tokyo fortress. Clad in a black-ninja suits with white trim, they approached the castle, running over snow barefoot to remain quiet, and cut up the defenders of the fortress with their tempered steel swords. [Source: T.R. Reid, the Washington Post]

Kira was captured in an outhouse, and beheaded. After marching through the streets of their hometown before cheering crowd, with Kira's head, the 47 samurai lined up in a row in front of Asano's tomb, announced the successful completion of their mission and all 47 of them committed seppuku (ritual suicide) as a punishment for their act of violence.

Japanese Poetry

Poetry-writing is sometimes regarded as a social activity. In the 10th century, poetry contests scored by a panel of judges were popular. “Renku-kai” ("linked verse") is a collective composition in which a group of poets sit around taking turns improvising on what has come before and helped along with a bottle of sake.

In the old days love letters were often written as waka poems. The handwriting was expected to be excellent. If it wasn’t the letter would be rejected without even being read. The paper was also carefully selected and often sent with a flower that bloom in the season when the letter was written. Somonka love poems consist of two tanka poems — one an expression of love, and the second a response by another person.

In the Edo Period, artists, writers, actors and other creative people gathered at poetry parties and composed ribald poems known as “mad verse.” One verse found on an image of a courtesan created around 1800 by Hokusai and the poet Santo Kyoden went: “Sometimes I turn into a cloud/like smoke from tobacco I have lit,/ other times I turn into rain/ which makes a client linger a bit.”

Haiku

See Separate Article

Kenko

Lance Morrow wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Around the year 1330, a poet and Buddhist monk named Kenko wrote Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa) — an eccentric, sedate and gemlike assemblage of his thoughts on life, death, weather, manners, aesthetics, nature, drinking, conversational bores, sex, house design, the beauties of understatement and imperfection. [Source: Lance Morrow, Smithsonian magazine, June 2011]

Kenko had been a poet and courtier in Kyoto in the court of the emperor Go-Daigo. It was a time of turbulent change. Go-Daigo would be ousted and driven into exile by the regime of the Ashikaga shoguns. Kenko withdrew to a cottage, where he lived and composed the 243 essays of the Tsurezuregusa. It was believed that he brushed his thoughts on scraps of paper and pasted them to the cottage walls, and that after his death his friend the poet and general Imagawa Ryoshun removed the scraps and arranged them into the order in which they have passed into Japanese literature. (The wallpaper story was later questioned, but in any case, the essays survived.)

For a monk, Kenko was remarkably worldly; for a former imperial courtier, he was unusually spiritual. He was a fatalist and a crank. He articulated the Japanese aesthetic of beauty as something inherently impermanent — an aesthetic that acquires almost unbearable pertinence at moments when an earthquake and tsunami may shatter existing arrangements.

Kenko yearned for a golden age, a Japanese Camelot, when all was becoming and graceful. He worried that “nobody is left who knows the proper manner for hanging a quiver before the house of a man in disgrace with his majesty.” He even regretted that no one remembered the correct shape of a torture rack or the appropriate way to attach a prisoner to it. He said deliberate cruelty is the worst of human offenses. He believed that “the art of governing a country is founded on thrift.”

Kenko’s Essays

Lance Morrow wrote in Smithsonian magazine: One or two of his essays are purely informational (not to say weird). One of my favorites is essay 49, which reads in its entirety: “You should never put the new antlers of a deer to your nose and smell them. They have little insects that crawl into the nose and devour the brain.” [Source: Lance Morrow, Smithsonian magazine, June 2011]

A sailor in rough seas may grip the rail and fix his eye on a distant object in order to steady himself and avoid seasickness. I read Kenko’s essays for a similar reason. “The pleasantest of all diversions is to sit alone under the lamp, a book spread out before you, and to make friends with people of a distant past you have never known.” Kenko is like a friend who reappears, after a long separation, and resumes your talk as if he had left the room for just a moment.

Kenko is charming, off-kilter, never gloomy. He is almost too intelligent to be gloomy, or in any case, too much a Buddhist. He writes in one of the essays: “A certain man once said, “Surely nothing is so delightful as the moon,” but another man rejoined, “The dew moves me even more.” How amusing that they should have argued the point.” He cherished the precarious: “The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty.” He proposed a civilized aesthetic: “Leaving something incomplete makes it interesting and gives one the feeling that there is room for growth.” Perfection is banal. Better asymmetry and irregularity.

He stressed the importance of beginnings and endings, rather than mere vulgar fullness or success: “Are we to look at cherry blossoms only in full bloom, the moon only when it is cloudless? To long for the moon while looking on the rain, to lower the blinds and be unaware of the passing of the spring — these are even more deeply moving. Branches about to blossom or gardens strewn with faded flowers are worthier of our admiration.”

Of houses, Kenko says: “A man’s character, as a rule, may be known from the place where he lives.” For example: “A house which multitudes of workmen have polished with every care, where strange and rare Chinese and Japanese furnishings are displayed, and even grasses and trees of the garden have been trained unnaturally, is ugly to look at and most depressing. A house should look lived in, unassuming.”

Kenko, Dante, Montaigne and Wodehouse

Lance Morrow wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Kenko was a contemporary of Dante, another sometime public man and courtier who lived in exile in unstable times. Their minds, in ways, were worlds apart. The Divine Comedy contemplated the eternal; the Essays in Idleness meditated upon the evanescent. Dante wrote with beauty and limpidity and terrifying magnificence, Kenko with offhand charm. They talked about the end of the world in opposite terms: the Italian poet set himself up, part of the time, anyway, as the bureaucrat of suffering, codifying sins and devising terrible punishments. Kenko, despite his lament for the old-fashioned rack, wrote mostly about solecisms and gaucheries, and it was the Buddhist law of uncertainty that presided over his universe. The Divine Comedy is one of the monuments of world literature. The Essays in Idleness are lapidary, brief and not much known outside Japan. [Source: Lance Morrow, Smithsonian magazine, June 2011]

Kenko wrote: “They speak of the degenerate, final phase of the world, yet how splendid is the ancient atmosphere, uncontaminated by the world, that still prevails within the palace walls.” As Kenko’s translator Donald Keene observed, there flows through the essays “the conviction that the world is steadily growing worse.” It is perversely comforting to reflect that people have been anticipating the end of the world for so many centuries. Such persistent pessimism almost gives one hope.

That is how Montaigne, in the midst of France’s 16th-century Catholic-Protestant wars, came to write his Essaies, which changed literature. After an estimable career as courtier under Charles IX, as member of the Bordeaux parliament, as a moderating friend of both Henry III and Henry of Navarre during the bloody wars of religion, Montaigne withdrew to the round tower on his family estate in Bordeaux. He announced: “In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michel de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out.... he has consecrated [this sweet ancestral retreat] to his freedom, tranquility and leisure.”

The wood over his doorway was inscribed to read, “Que sais-je”—“What do I know” — the pre-eminent question of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. So, surrounded by his library of 1,500 books, he began to write. Montaigne followed a method of composition much like Kenko’s. In Japanese it is called zuihitsu, or “follow the brush” — that is, jot down the thoughts as they come to you. This may produce admirable results, if you are Kenko or Montaigne.

I find both to be stabilizing presences. A person’s sense of balance depends upon the inner ear; it is to the inner ear that such writers speak. Sometimes I get the effect by taking a dip in the Bertie Wooster stories of P. G. Wodehouse, who wrote such wonderful sentences as this description of a solemn young clergyman: “He had the face of a sheep with a secret sorrow.” Wodehouse, too, would eventually live in exile (both geographical and psychological), in a cottage on Long Island, remote from his native England. He composed a Bertie Wooster Neverland — the Oz of the twit. The Wizard, more or less, was the butler Jeeves.

Wodehouse, Kenko, Dante and Montaigne make an improbable quartet, hilariously diverse. They come as friendly aliens to comfort the inner ear, and to relieve one’s sense, which is strong these days, of being isolated on an earth that itself seems increasingly alien, confusing and unfriendly. It is a form of vanity to imagine you are living in the worst of times — there have always been worse. In bad times and heavy seas, the natural fear is that things will get worse, and never better.

Dante, Kenko and Montaigne all wrote as men exiled from power — from the presence of power. But power, too, is only temporary. Kenko in one essay wrote: “Nothing leads a man astray so easily as sexual desire. The holy man of Kume lost his magic powers after noticing the whiteness of the legs of a girl who was washing clothes. This is quite understandable, considering that the glowing plumpness of her arms, legs and flesh owed nothing to artifice.”

Image Sources: 1) onmark productions 2) and 3) National Museum in Tokyo 4) Japan Arts Council 5) Ghibli Studio 6) British Museum 7) Mizoguchi film

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2012