JAPANESE POETRY

Basho staue in Hiraizumi

Iwata Predecture Poetry-writing is sometimes regarded as a social activity in Japan. In the 10th century, poetry contests scored by a panel of judges were popular. “Renku-kai” ("linked verse") is a collective composition in which a group of poets sit around taking turns improvising on what has come before, helped along with a bottle of sake.

In the old days love letters were often written as waka poems. The handwriting was expected to be excellent. If it wasn’t the letter would be rejected without even being read. The paper was also carefully selected and often sent with a flower that was in bloom in the season when the letter was written.

In the Edo Period, artists, writers, actors and other creative people gathered at poetry parties and composed ribald poems known as “mad verse.” One verse found on an image of a courtesan created around 1800 by Hokusai and the poet Santo Kyoden went: “Sometimes I turn into a cloud/like smoke from tobacco I have lit,/ other times I turn into rain/ which makes a client linger a bit.”

Poem boxing is a “sport” that was launched in 1999 and has developed an enthusiastic following over with an annual championship held at Nekkei Hall in Tokyo in October. The bouts consist of one round in which contestants are allowed three minutes to recite a poem. Sponsored by the Japan Reading Boxing Association, the event has individual and team divisions.

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Poetry Terms ahapoetry.com ; Classical Japan Poetry classical-japanese.net/Poetry ; Literature Sites Japanese Literature Home Page www.jlit.net ; History of Japan’s Literature kanzaki.com/jinfo ; Japanese Literatures Resources Page mockingbird.creighton.edu ;

Haiku Haiku for People toyomasu.com ; Haiku Home Page haiku.insouthsea.co.uk ; Simply Haiku Quarterly Journal simplyhaiku.com ; Association of Haiku Poets famille.ne.jp/~haiku ;Haiku of Kobayashi Issa haikuguy.com ; Wikipedia article on Haiku Wikipedia

Basho Basho Books and Links opening.hefko.net/gi_basho ; Basho’s Narrow Road to the Deep North darkwing.uoregon.edu ; 31 Translations of the Basho Frog Poem bopsecrets.org ; Basho’s Life darkwing.uoregon.edu ;

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TALE OF GENJI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BASHO, HAIKU AND JAPANESE POETRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC 20TH CENTURY JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN LITERATURE AND BOOKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HARUKI MURAKAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS AND WESTERN WRITERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Early Japanese Poetry

Poems in the 7th century were written on wooden strips known as mokkam. One 9.1-centimeter-long paddle-shaped strip dated to A.D. 680 found in Asuka in Nara contained a pair of “ anyoshu”poems. The translation of one poem reads: “I hope to see whitecaps lapping at the shore on a calm morning, but the wind doesn’t blow.”

The first major collection of native poetry, written with Chinese characters, was the “Man — yoshu “( “The Ten Thousand Leaves”), which contains verses, chiefly the 31-syllable “waka”, that were composed in large part between the mid-7th and mid-8th centuries. The earlier poems in the collection are characterized by the direct expression of strong emotion but those of later provenance show the emergence of the rhetorical conventions and expressive subtlety that dominated the subsequent tradition of court poetry. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The “Manyoshu” is a 20 volume compilation, assembled in A.D. 770, with 45,000 poems by numerous men and women from all walks of life. One poem from the Manyoshu goes: “If just a moment, my dear friend, / I could have watched together with you / The blossoms of the wild cherries / On the mountain with the hills, / I would not be so lonely like this.”

A revolutionary achievement of the mid- 9th century was the development of a native orthography (“kana”) for the phonetic representation of Japanese. Employing radically abbreviated Chinese characters to denote Japanese sounds, the system contributed to a deepening consciousness of a native literary tradition distinct from that of China.

During the Heian Period (794-1185) “waka” poems were developed. Also known as “tanka”, these 31-syllable poems in a 5-7-5-7-7 form were popular among aristocrats and court ladies and a collection of them call “Kokinshu” ( “; Waka Collection from Ancient and Modern Times”) was compiled in 905 and was the first of 21 imperial anthologies of native poetry assembled in the early 10th century. The compactness of tanka obliged poets to resort to suggestion as a means of expanding the content of their lines, a literary device which has been characteristic of Japanese poetry ever since.

“Ogura Hyakunin Isshu” (“One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each”) is a classic collection of waka poems believed to have been compiled in the 13th century. Like its title says it is a collection of 100 poems each by a different poet. The poems are thought to have been written between the 7th and 13th centuries. Many Japanese have memorized at least one poem. The poems are the basis of a card slap game played in Japan around New Year.

One famous poem by Sone no Yoshitada goes:

“Crossing the Straits of Yura

the boatman lost the rudder.

The boat’s adrift

not knowing where it goes.

Is the court of love like this?”

Another, by Semimaru, goes

“So this is the place!

The crowds,

coming,

going,

meeting,

parting;

friends

strangers

known

unknown?

Osaka Barrier “.

The chief development in poetry during the medieval period (mid-12th to 16th century) was linked verse (“renga”). Arising from the court tradition of “waka”, “renga “was cultivated by the warrior class as well as by courtiers, and some among the best “renga “poets, such as Sogi, were commoners.

Twelfth Century Poem Found on Pottery

In January 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: Ancient earthenware with part of the old Japanese poem "iroha Uta" written on it found in the town of Meiwa, Mie Prefecture, has been confirmed as the oldest known copy of the poem in hiragana, according to the prefectural Saiku Historical Museum. The museum said that the dish-shaped earthenware was made in the late 11th or early 12th century. It was found at the national historic site of Saiku, a palace of the Saio princess, who was appointed from among unmarried Imperial princesses to serve at the Ise Grand Shrines. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 26, 2012]

The museum considers the earthenware to be a valuable discovery illustrating how court culture spread from the then capital of Kyoto during the Heian Period (794-1192) to Saiku, currently the central part of Mie Prefecture. The four pieces combine to form a fragment 6.7 centimeters long, 4.3 centimeters wide and 1 centimeter thick.

When combined, the surface of the fragments bear the hiragana characters "nu ru wo wa ka" on one side, and "tsu ne na ra" on the other. They are part of the "iroha Uta" poem, which uses each hiragana character once. It is believed to have been written by local women working in Saiku as a way of learning hiragana.

From 670 to about 1330, Saiku served as as a palace of the Saio, whose main duty was to visit the Ise shrines three times a year in place of the emperor. Ryukoku University Visiting Prof. Koichi Fujimoto, former chief researcher on cultural property at the Cultural Affairs Agency and Japanese history expert, said, "It's an important artifact that indicates how culture in the capital spread to the Ise area before other areas through the Saio's visits from Kyoto."

Haiku Poetry

Haiku are short, chant-like poems that originated as the first verse of longer linked verse “ haikai” poems. Developed during Edo Period (1603-1867), they have three and 17 syllables made up of unrhymed phrases of five, seven and five syllables. The purpose of these poems is to capture the essence of nature by evoking a setting or season with elegant minimalism. The Los Angeles Times described haiku as “daringly simple. Remarkably expressive. You can do it too.”

In haiku minute details, lightness and looking at things from a skewed angle are of utmost importance. The last line should provide some kind of twist. The writer Scott Gordon wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, haiku are "extremely short and pithy poems that are playful, enigmatic, hyperbolic, tightly woven, sometimes unfathomable" with "metrics and rhythm found not only in a poetry, but in the Japanese language itself." Senryu uses the same 7-5-7 syllable form as haiku but uses it to express satire, social commentary and distaste.

Henshu Techo wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Haiku poet Kyoshi Takahama (1874-1959) once penned an essay titled "Hiden" (secrets). To compose quality haiku, one must sharpen one's mental facilities and calm the mind. To accomplish this, Takahama recommended "yawning continuously." [Source: Henshu Techo, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 26 2012]

Haiku poet Shuson Kato (1905-1993) composed a haiku about his granddaughter's pillow, which was filled with rose petals. Hanabira mugen/ yume mata mugen/ bara-makura (Countless petals/ unlimited dreams/ a pillow of roses)

Haiku remains important in Japan today. Many Japanese still attend twice-monthly meetings to recite and study haiku; the Emperor presides over a national haiku-writing contest; and one Japan's most popular game,often televised around New Year Day, features players who are given a line from a haiku poem and have to quickly slap a card with the correct poem on it.

Noteworthy haiku poets include Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693), the creator of Ukiyo Zoshi prose; and Karai Senryu (1718-90), creator of the “senryu” style of poetry which has the same structure but has a satirical and humorous content.

Among the Westerners who tried their hand at haiku were Jack Kerouac and Ezra Pound. Kerouac’s” Book of Haikus” (edited by Regina Weinrech, Penguin Putnam, 2002) was released 35 years after his death. A typical example of his haiku goes: “The Windmills of /Oklahoma look/ In every direction.”

Basho

Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) is regarded as Japan’s greatest haiku poet. Nearly every Japanese can recite at least one of his poems by heart. For many he is the first writer that kids study in school “in any exciting or serious way” Thousands of people each year make pilgrimages to his birth place, burial shrine and places that he traveled and wrote about.

The traveler Helen Tanuzaki wrote: “He’s like a quirky philosopher tour-guide who pretty much leaves readers alone to experience traveling in those remote places for themselves. Rather than trying to account for things, he just feels the obligation to take note of them. A vast striving for connection.” On staying true to Basho’s style The poet laureate Robert Haas wrote: “Avoid adjectives if scale, you will love the world more and desire it loess.”

Basho’s Life

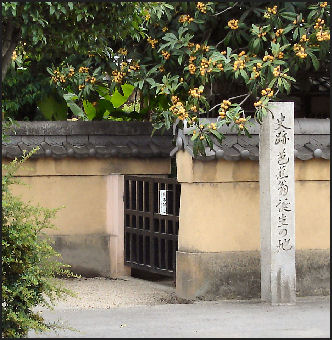

Basho's reported birthplace,

Seika in Iga Prefecture Basho was born into a family of samurai in Iga Ueno (20 miles east of Nara) in Mie prefecture but spent little time there. His father was a minor samurai who might have made ends meat by teaching children to write. Basho studied to become a samurai himself and may have studied to be a ninja (Ueno is famous for ninjas) and abandoned that life after the lord he pledged himself to died when Basho was 22. [Source: Howard Norman, National Geographic, February 2008]

Basho's lord was a patron of the arts and took the time to teach him poetry and literature. After the lord died, Basho set out for Kyoto to find a new life. In Kyoto, he hung out with poets and artists. He learned the craft of poetry from Kigin, a prominent Kyoto poet and was inspired by Chinese poetry and Taoism.

When he was in his late 20s, Basho moved to Edo (Tokyo), where he established himself as a poet and a haiku teacher and assembled the Basho school made up of friends, students and sponsors. In Basho’s time Edo was a vibrant city that hadn’t been around all that long and, for many, was a place filled with inspirations and opportunities. The poet lived in a small house on the Sumida River built by one of his students. It was in Edo that he began calling himself Basho after one of his students presented him with a stock of “ basho” tree, a species of banana.

Basho became famous in Edo but if anything that increased the melancholy tone of his work. He didn’t like the demands made on his time and yearned for a simple and seemed to be most happy in nature, sitting under a tree watching bugs or farmers. He became very distraught when a fire burned his house to the ground and destroyed much of Edo.

Basho walked all around Japan. In 1684, he took the first of several journeys that provided material and inspiration for much of his best poetry. On his first journey westward from Edo he wrote “ Journal of a Weather-Beaten Skeleton”. Subsequent works “ Kashima Journal” and “ Manuscript in a Knapsack” features a mixture of haiku and prose( “ haibu”). After returning to Tokyo he studied Zen, which also had a profound impact on his poetry. In the middle of his forth journey he died in Osaka. After his death his disciples popularized the haiku form.

Book: “Basho's Haiku, Volumes I and II” by Toshiharu Oseko.

Basho's Poetry

Howard Norman wrote in National Geographic: “Using plain language in the service of spiritual insight, Basho raised [haiku] to literature, each poem like a polished stone that, when dropped in water, creates an infinity of ripples.”

In his early years in Kyoto Basho wrote haikai and then haiku. He published his first haiku under various names that had some personal meaning to him. One name, Yosei or “green peach,” was a tribute tp the Chinese poet Li Po (“white plum”).

Basho was influenced by Chang-tzu, a Chinese sage who advocated looking at natural things as they are. Among Japanese poets he greatly admired were Saigyo (1118-1190) and Soshi (1421-1502), the master of renga linked verse. Much has been written about the influence of Zen koans (short riddles intended to bring about a sudden insight in the listeners) on Basho's work and Basho’s fondness of combining unusual elements such “the cool fragrance of snow” or a cricket chirping under a samurai helmet.. In the later part of his career he invented his own principles of poetry which he called “sabi” (meaning “spare, lonely beauty”).

Many of Basho’s poems allude to verses written earlier by poets he admired. Basho liked to tell his students he “held forth” with the great Japanese and Chinese poets of the past and called one such meeting a “conversations with ghost and ghost-to-be.” In one poem Basho wrote: “Days and months are eternal travelers, / As are the years that come and go.”

Basho's Poems

In his ode to traveling Basho wrote: "Traveler’s heart/ never settled long in one place/like a portable fire" and “The moon is the guide/ Come this way to my house/ so saying, invites the host of a wayside inn.” While traveling in Arano he wrote: "On a withered branch/a crow is perched/an autumn evening."

Basho wrote: “Summer grass”/ “tis all that remains/ of warrior’s dreams.” He also wrote: “All June’s rainy days/ Have left untouched the Hall of Light/ In beauty still ablaze and silence. Penetration the rocks/ The cry of the cicada. “ Some of his stuff was quite crude, One goes: “Fleas and lice biting;/ Awake all night/ A horse pissing close got my ear”).

Basho often wrote about nature. One famous Basho poem goes:

“The old pond

A frog jumps in

The sound of water”

Another translation for the same poem goes:

“Listen! a frog

Jumping into the stillness

Of an ancient pond!”

One famous Basho poem, written after finding a man's grave in a bamboo grove, goes: "The vicissitudes of life/ Sad, to become finally/ a bamboo shoot." Another famous poem reads: "In the mountain village/ the Manzai dancers are late/ plum blossoms." One welcoming Emperor Akihito to the United States, President Clinton recited yet another famous Basho poem: "Nearing autumn's close/ my neighbor/ how does he live/ I wonder."

Basho's Journey in 1689

In March 1689, at the age of 46, and in frail health, Basho took off on a long journey to honor the 500th anniversary of the death of the poet Saigyo, seeking out places described in poems he admired and visiting sites known as, “uta -makura”, or poetic pillows, such as shrines, mountains, cherry groves and other memorable spots described by other writers — places he wanted to see before he died.

“The road gods beckoned.” Basho set off from his home in Fukugawa, Tokyo to wander like “a speck of cloud blowing in the wind and hoping to “feel the truth of the old poems.” “There we did begin,/ Cloistered in that waterfall./ Our summer discipline.”

Basho's grave in

Otsu, Shiga “Each day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.” He traveled inland to northern Japan. After reaching Sendai, he traveled further north and then cut across the country to Japan’s west coast and then traveled southward near the coast to Kanazawa and finished his journey in Ogaki, Gifu Prefecture.

Basho dressed like a Buddhist monk and traveled on horseback and on foot with a shoulder bag, covering around 40 kilometers a day. Altogether he spent five months on the road and covered 2,000 kilometers and was accompanied on much of the journey by his student Sora. Along the way Basho stayed in travelers inns and the homes of students and disciples who put him up in return for poetry lessons.

Basho wrote poems along the way and when he finished. The result — “Okuno Hosomichi” (“The Narrow Road to the Deep North”) — is regarded by many as his masterpiece. The 20th century Buddhist poet Miyazawa Kenji said, “It was as if the very soul of Japan had itself written it.”

Basho chose to finish his journey in Ogaki, not Tokyo or his hometown, because he came to see the haiku poet, Tani Bokuin, whom he greatly admired. Basho spent about six months in Ogaki and then went to Ise by boat. “sadly, I Part from you;/ Like a clam torn from its shell,/ I go, and autumn too.”

Image Sources: 1) Books, Amazon.com 2) Photos Wikipedia and Japan Zone 3) Haiku, illustration JNTO

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013