TALE OF GENJI

“Tale of Genji” is Japan's most famous classical literary work. Regarded by some scholars as the world's first important novel and the first psychological novel, it was written as an epic poem by Murasaki Shikibu (975-1014), a lady from the Japan Imperial court, between A.D. 1008-20.

As a literary treasure “Tale of Genji” is to the Japanese what “The Odyssey” and “The Iliad” are to the West. It is written in episodes as if serialized in a magazine. It was written mostly in hiragana as women at the time were not supposed to learn kanji (Chinese characters).

“The Tale of Genji” is the story of handsome Prince Hikaru Genji. The first half deals the life of Genji. The second half deals with period after Genji's death especially in regard to the tragedies of his son, his grandson and three daughters of a ruined businessman. Genji means the "shining one.”

The “Tale of Genji” story features an expressive narrative and a diverse cast of characters and is filled with details about court life in the mid Heian period and aesthetic pursuits that are still alive today: waka poetry, gakaku court music, noh and the tea ceremony.

Although there is no historical documentation that indicates when Murasaki Shikibu began or completed the “Tale of Genji”, her diary indicates that she at least completed the tale’s fifth Wakamurasaki chapter on November 1st 2008 while staying at Ishiyamadera temple in Otsu, not far from Kyoto. The 1000th anniversary of the novel in 2008 was celebrated with a special ceremony in Kyoto attended by the Emperor and Empress in which November 1st was declared Classics day.

It is said that during her stay at Ishiyamadera temple Murasaki saw a full moon rise over Lake Biwa and got the idea for the Suma chapter in which Genji remembers his glory days in Kyoto while looking at a full moon from a beach in Suma, currently in Hyogo Prefecture, to which he had been banished because of a scandalous romantic liaison.

Good Websites and Sources: The Tale of Genji.org (Good Site) taleofgenji.org ; Murasaki Shikibu Biography womeninworldhistory.com ; Murasaki Shikibu?Bio, Quotes and Links infionline.net ; Tale of Genji Summary and Characters mcel.pacificu.edu ; Tale of Genji Links meijigakuin.ac.jp ; Library of Congress Copy Dated to 1654 lcweb4.loc.gov ; Tale of Genji Illustrated Scroll dartmouth.edu ;Collection of Japanese Literature with Genji Translation gutenberg.org ; Liza Dalby’s Genji Site lizadalby.com ; Japan Costume Museum iz2.or.jp/english ; Genji Net genji.co.jp ; Tale of Genji in Japanese sainet.or.jp ; Ishiyamadera Temple (Otsu) is said to be the place where Murusaki Shikibu wrote important parts of the “The Tale of Genji”.

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BASHO, HAIKU AND JAPANESE POETRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC 20TH CENTURY JAPANESE LITERATURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN LITERATURE AND BOOKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HARUKI MURAKAMI Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS AND WESTERN WRITERS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Tale of Genji” (Penguin Classics) by Royall Tyler and Murasaki Shikibu Amazon.com; “The Pillow Book” (Penguin Classics) by Sei Shonagon and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com; “Emperor and Aristocracy in Heian Japan: 10th and 11th centuries” by Francine Herail and Wendy Cobcroft (2013) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 2: Heian Japan” by Donald H. Shively and William H. McCullough Amazon.com; “The Halo of Golden Light: Imperial Authority and Buddhist Ritual in Heian Japan” by Asuka Sango Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Japanese Arts of the Heian Period, 794-1185" by John M Rosenfield Amazon.com

Structure and Themes of the Tale of Genji

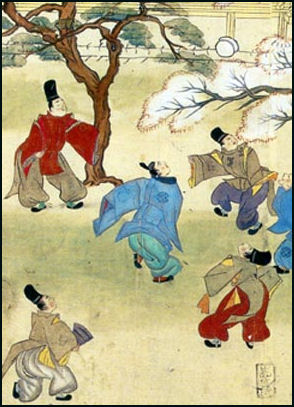

depecition of the shell game Ambitious and graceful, and a great story too, the “Tale of Genji”, describes the power of women and the love affairs of 10th century aristocracy with delightful detail. Woven into the narrative are wonderful psychological character portraits, sensual descriptions of Japanese nature and a religious philosophy based on the awareness of life's transitions.

“Tale of Genji” has many layers and brilliant insights into things that are still relevant today. Donald Keene, an expert of Japanese literature at Columbia University, said, the novel “should be regarded as something more than a novel. It makes readers want to known more about a whole world.” Genji translator Jakucho Setouchi said, “The tale describes everything about life, such as what a human being is and what love is.”

There are 800 poems and 54 chapters in the original version of the novel. The English translation of “Tale of Genji” is over 1,000 pages long and organized in six sections that are thematically linked together by a series of sexual adventures centered around Prince Genji. Unlike the relatively, short concise sentences of modern Japanese literature, the sentences from “Genji” tend to be very long, flowing from one episode to another, with detailed accounts of the characters. Waka poems are exchanged as love letters. There is no definitive ending to the story. Instead it seems to fade out.

Important themes include the changing of the seasons expressed with snow, fireflies, morning dew, autumn leave dances, bush warbler songs, and the moon and “mono no aware”—“the awareness of the transience of life and things” and “the gentle sadness at their passing”. Many of the places named in the novel are real places that still exist in some form.

Prince Genji

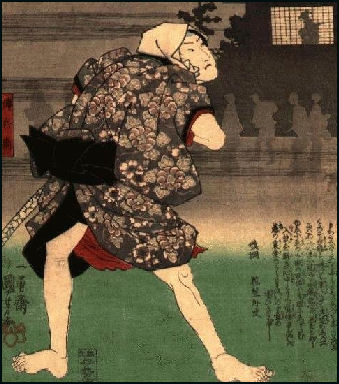

Genji ukiyo-e There are 430 characters in “The Tale of Genji”. The main character, Prince Hikaru Genji, is believed to be modeled after Minamoto no Toru, a minister in the early Heian period (794-1192). Some see the novel as a moralistic tale because Prince Genji had an affair with his father’s mistress and was punished by having his own wife seduced by another man.

Prince Genji is the beautiful son of the Emperor by a courtesan. He is a strikingly immoral Don-Juan-type character in search of woman like his mother. Among the women he seduces are a rival’s daughter his stepmother and her young niece Murasaki.

Genji is cold and seemingly without a conscious. His main redeeming features are his good looks and athleticism. Although Genji’s affairs with the women are selfish he remains generous to the women after the affairs are over and is especially considerate to the elderly. About 70 percent of Genji’s wives and lover eventually become nuns.

Women in the Tale of Genji

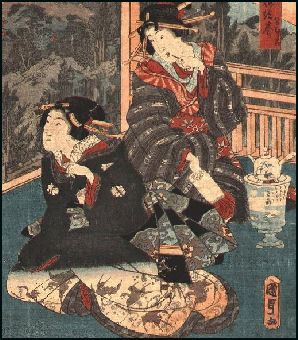

Genji ukiyo-e While Prince Genji may be the main character in the novel but the real focus of the book, many think, is the thoughts and emotions of the women who love him. Respected author and Buddhist nun Jakucho Setouchi told the Daily Yomiuri, “Shikibu wrote about the pain and joy the women felt in their relationship with Genji and how they overcame their grief. Because she wrote about women’s emotions and there desires, the tale is still enjoyed 1,000 years later.”

Some scholar say the novel was far ahead its time in that it expressed the inner thoughts and emotions of the characters. Keene told the Daily Yomiuri, “Let’s take the Greek stories, We never see inside the person. We know what they did, but never really think about their feelings. In so much of “Genji” the different people in it are independent of action.” The “The Tale of Genji” “presents emotional conflicts and depicts people’s sensitivity.”

Many Genji’s lovers sit around waiting for him to show up and seem to take great pleasure in being exploited. Rokujo no Miyasudokoro is a Genji lover whose jealously becomes viscous game resulting in the murder of her rivals.

The Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami wrote: Rokujo “becomes so consumed with jealousy over Genji’s main wife, Lady Aoi, that she turns into an evil spirit that possesses her. Night after night she attacks Lady Aoi in her bed until she finally kills her...But the most interesting part of the story is that Lady Rokuju has no inkling that she’d become a living spirit. She’d have nightmares and wake up only to disocver that her long black hair smelled like smoke. Not having any idea what was going on, she was totally confused. In fact the smoke came from the incense the priests lit as they prayed for Lady Aoi. Completely unaware of it, she been been flying through space and passing down the tunnel of her subconscious into Aoi’s bedroom.”

Passages and Details from the Tale of Genji

kemura game There are wonderful descriptions of perfumeries and alchemists who concocted fragrances based on a person's aura and destiny. There is also a lively depiction of "grading women on a rainy night." One of the most famous passages from the “Tale of Genji” is a scene in which a noblemen spies on a princess and her ladies in waiting, all dressed in transparent undergarments, while they try to cool themselves on a hot summer day with a block of ice.

"Making a great effort," the passage goes, "they managed to break it. Each took a piece in her hand. Some even behaved quite vulgarly, placing it on their heads or holding it to their breasts. Another wrapped a bit in paper and presented it to the princess, but she held out her very lovely hands and let her wipe them. 'No, I'd better not take it,' she said, 'the dripping is a bother.'"

The details can be excruciating. In one passage Murasaki describes how to fold a letter, the kinds of paper and ink to use, the thickness of the strokes, the penmanship and appropriate decorations. If a man received a letter from a women with sloppy handwriting or written on poor quality paper he would likely not want ti have anything to do with her.

Author of the Tale of Genji

Murasaki Shikibu (973-1014), the author of “Tale of Genji”, was interesting woman. Holding the same stature in Japan as Homer, Shakespeare and Proust in the West, she was married once (maybe twice) and may have been the mistress of two powerful princes (one of whom was immortalized as Genji). In addition to Genji, she wrote hundreds of deeply passionate love poems. Many of them are "occasional poem" written as dialogues between two people.

Murasaki Shikibu was probably not the name she was give at birth. The name Murasaki came from a popular character in the novel, Murasaki no Ue, one of the Genji’s wives. Shikibu comes from her father, Shikibuo-no-ju, who served the aristocracy as a Chinese literature scholar. Murasaki means "purple" and "agrimony," a plant used to make purple dye. Shikibu means "the bureau of ceremonial" (her father and brother were bureaucrats).

Women became leaders in literature in Murasaki’s time because they were still required to be versed in the Chinese classics. Their names however were not usually found in historical documents, with the exception of the Empress.

Murasaki Shikibu’s Life

Murasaki Shikibu [978?-1026?] is the woman who wrote Genji, As is true with Shakespeare little is known about the details of Murasaki’s life and even the dates of the her birth and death are in question. There are few references of her in contemporary documents. Some scholars claim she didn't even write all of “Tale of Genji” by herself.

Murasaki was married when she was 27 or 28 and had a daughter but here husband died less than three years after they were married, Murasaki was commissioned by Emperor Ichijo (980-1011) and the nobleman Fujiwara no Michinaga (966-1027). Fujiwara hired her to be a servant for his daughter Shushi who was one of the Emperor’s wives. Murasaki was already well known at that time and it was thought that he presence would boost the status of the salon of Fujiwara no Michinaga’s daughter and catch the eye of the Emperor and improve her chances of bearing a son for the Emperor.

Murasaki’s arrangement allowed her to devote much time to her writing and gave her an intimate look at imperial court life. But after the a prince was born to the Emperor and Michinaga’s daughter, Murasaki was no longer needed. She became a nun. The last 10 chapters of the novel are believed to have been written when she was a nun.

Kiyoyuki Higuchi wrote: “The father of Murasaki Shikibu was Fujiwara-no-Tametoki [died, 1029], Governor of Echizen, and her mother was the daughter of Fujiwara-no-Tamenobu, Governor of Settsu. In other words, Murasaki was born into the status of zuryo [provincial governors who resided in those localities while on duty], the lowest rung of the attendant nobility. [Zuryo were high-ranking officials in the overall bureaucracy but were the lowest of the elite group of officials who served the emperor directly as courtiers. Their court rank would typically be the fifth grade. They were on the borderline between the elites officials in the emperor’s court and the large numbers of rank-and-file bureaucrats occupying the lower levels of officialdom.] However, [her husband, Fujiwara] Nobutaka died [in 1001] while Murasaki was giving birth to her daughter Kenshi. These circumstances forced Murasaki into a lonely lifestyle filled with uncertainty as she raised her daughter alone. [Source: “Why is there no talk of food or bathing in the Tale of Genji?”, Himitsu no Nihonshi (“Secret History of Japan), Chapter 3, Section 1 by Kiyoyuki Higuchi, Shodensha, 1988, pp. 29-36. translation by Gregory Smits ++]

“It was after this time that she began creating her masterpiece. Moreover, she worked in the night, while her child slept, writing while staying close to the lamp. Out of this poor, lonely, and dark lifestyle came something quite the opposite: a masterpiece featuring the unfolding of a dream-like romance between an ideal male protagonist and over twenty beautiful women (though some unexpectedly ugly women like Suetsumuhana also make an appearance), interwoven with images of women consumed by their anxieties and the providential workings of karma. ++

“Having accompanied her parents during their terms as provincial governors, her life after their deaths must have been difficult. Therefore, she later became an attendant of [royal consort] Jotomon-in [988-1074]. To put it in today’s terms, this widow’s job search was a success. Because she had to work to get by, she began her great literary project. I suspect that Murasaki created this fantasy world as an alternative world for which she yearned—in contrast to the reality of her situation.” Jotomon-in gathered around her as attendants some of the best writers of the time. Her entourage functioned as Japan’s first literary salon.” ++

Book: “The Tale of Murasaki” by Liza Dalby (Doubleday, 2000) is a fictional story extrapolated from Murasaki's life.

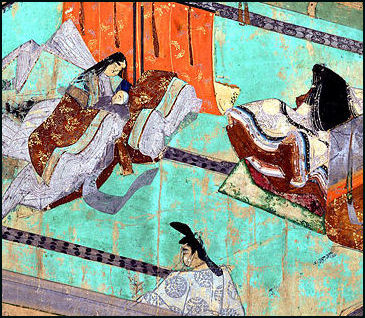

Tale of Genji, scene from Chapter 5

Translations of Tale of Genji

The respected author and Buddhist nun Jakucho Setouchi spent four years writing a contemporary version of “Tale of Genji”, which was much easier for ordinary Japanese to understand. It sold 2.83 million copies. Setouchi said, “I believe the tale was written like a contemporary newspaper of magazine serial.”

”Tale of Genji” has been translated into English three times, by Arthur Waley in the 1920s and 30s, by Edward G. Seidenesticker in 1976 and by Royal Tyler, published by Viking.

The translations by Waley, first published between 1925 and 1933, are especially good. Translations by Seidensticker and Tyler are also good. Many Western readers are turned off by its length. A manga version of “The Tale of Genji” has sold 16 million copies since ut was introduced in 1980.

There is no original manuscript by Murasaki Shikibu. The current standard text is based on the Aobyoshi-bin version which was transcribed about 200 years after the original manuscript was written and was edited by Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241), an acclaim poet and compiler of literature.

In July 2008, a bound manuscript with all the chapters of “The Take of Genji” was found in a lacquer-covered box in a family residence in Tokyo. The volumes, dated to Muromachi period (1333-1568), are 19.6 centimeters long and 15.1 centimeters wide and have a uniform cover sheet decorated with powder derived from seashells.

Image Sources: 1) National Museum in Tokyo 2) British Museaum 3) 4) 5) Liza Dalby's Genji website 6) Japan Zone

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2010