EARLY HISTORY OF CHINESE FILM

Spring in a Small Town Motion pictures were introduced to China in 1896, but the film industry was not started until 1917. During the 1920s film technicians from the United States trained Chinese technicians in Shanghai, an early filmmaking center, and American influence continued to be felt there for the next two decades. In the 1930s and 1940s, several socially and politically important films were produced. [Source: Library of Congress]

The first film was shown in Shanghai in 1896, a year after the first film was shown in Paris by the Lumiere brothers. The first Chinese-made film “Conquering Jun Mountain”, was made and shown in 1905.During the 1930s the leftist film making movement was active. Memorable films from this dark genre included Xia Yan’s “Torrents” (1933) Yuam Muzhi’s “Street Angel” (1937) and She Xiling’s “Crossroad” (1937). The film scene in the 1940s was more chaotic and fractured. Many “blue” movies and horror films were made. Among the handful of classics from this period are Cai Chusheng’s “Spring River Flows Eastward” (1947), She Yu’s “Light of a Million Hopes” (1948) and Chen Baichan’s “Crow and Sparrow” (1949).

During the 43 years from 1905 to 1948, China progressed from showing only foreign-made films to shooting its own and from using foreign funds to filming independently. Eventually, China became strong enough to develop its own national cinema. Family ethics and social issues were in vogue mainly in the 1920s and 1930s. Most of the works on family ethics drew material from the life of urban residents in the lower social strata or the petty bourgeoisie and showed love affairs, marriages, affairs concerning ethics, or household affairs. Films on social issues courageously exposed the most grim and pressing problems confronting Chinese society. [Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

In a review of the book “Fiery Cinema” on film in China from 1915 to 1945, Jean Ma wrote: “Bao demonstrates, cinema itself was a moving target” at that time. “Not only did its identity undergo a continuous refraction as an art form of entertainment, instrument of communication, scientific object, sensory-bodily prosthesis, and political weapon; as part of a larger ensemble of new technologies, cinema also stood at the center of an intense interrogation of the very concept of medium in modern China. Bao navigates a stunningly expansive territory as she delineates these assemblages and uncovers the connections among the beginnings of the martial arts film, symbolist poetry, physics, and Bergsonian philosophy; among theories of acting, hypnotism, and early televisual technology; among early sound films, glass architecture, and theories of montage; among education, propaganda, and wireless technology. [Source: Reviewed by Jean Ma, Stanford University, Jean Ma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, February, 2016; Book: “Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915-1945" by Weihong Bao (University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

Dominant film types were emotional dramas in the 1930s and war movies in the 1940s. According to Christopher Rea, a professor at the University of British Columbia, in the 1930s and 40s, Chinese cinema had light sabers. And copies of Mickey Mouse. And full frontal male nudity." , Rea wrote on book on the subject — “Chinese Film Classics, 1922-1949" (Columbia University Press, 1921) — and made the films featured in the book available via the YouTube channel Modern Chinese Cultural Studies and the website chinesefilmclassics.org. [Source: Christopher Rea, Rediscovering Early Chinese Cinema: From the Archive to the Internet, April 8, 2021; Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; YouTube Playlist: youtube.com/playlist ]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS ACTRESSES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; MAO-ERA FILMS factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS — MADE ABOUT IT AND DURING IT factsanddetails.com ; RECENT HISTORY OF CHINESE FILM (1976 TO PRESENT) factsanddetails.com ; MARTIAL ARTS FILMS: WUXIA, RUN RUN SHAW AND KUNG FU MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; BRUCE LEE: HIS LIFE, LEGACY, KUNG FU STYLE AND FILMS factsanddetails.com ; TAIWANESE FILM AND FILMMAKERS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. “The Goddess” (dir. Wu Yonggang)is available on the Internet Archive at archive.org/details/thegoddess . “Shanghai Old and New” is also available on the Internet Archive at archive.org ; The best place to get English-subtitled films from the Republican era is Cinema Epoch cinemaepoch.com. They sell the following Classic Chinese filsm: “Spring In A Small Town”, “The Big Road”, “Queen Of Sports”, “Street Angel”, “Twin Sisters”, “Crossroads”, “Daybreak Song At Midnight”, “The Spring River Flows East”, “Romance Of The Western Chamber”, “Princess Iron Fan”, “A Spray Of Plum Blossoms”, “Two Stars In The Milky Way”, “Empress Wu Zeitan”, “Dream Of The Red Chamber”, “An Orphan On The Streets”, “The Watch Myriad Of Lights”, “Along The Sungari River”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“General History of Chinese Film I” by Ding Yaping Amazon.com; “Chinese Film Classics, 1922–1949" by Christopher G. Rea Amazon.com; “Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915-1945" by Weihong Bao Amazon.com; “Shanghai Filmmaking” by Huang Xuelei; Amazon.com; “Cinema Approaching Reality: Locating Chinese Film Theory” by Victor Fan (University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Amazon.com; “An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937" by Zhang Zhen (University of Chicago Press, 2005). Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Introduction of Film to China

Conquering Jun Mountain,

the first Chinese film Films were introduced into China at the end of the 19th century, and the market was mainly dominated by foreign films in the early period. China was one of the earliest countries exposed to the motion picture as because Louis Lumière sent his cameraman to Shanghai a year after inventing cinematography. The first recorded screening of a motion picture in China took place as an "act" on a variety bill. Early film was not well received by opera fans who felt that film threatened their favored art form. Even so film was quickly embraced and compared with the old art form of shadow puppetry and called “electric shadow play.”

[Source: Wikipedia]

On December 28, 1895, Dr. Louis Lumiere showed two movies in the Grand Cafe on Boulevard des Capucines in Paris. The movies were Workers Leaving the Lumiere Factory and The Train Pulls into the Station. That event is considered the official birth of the movies. On August 11, 1896, a foreign film was shown at Youyicun of Xuyuan in Shanghai, marking the introduction of movies into China. The first-ever screening of what locals called “Western shadow plays” was held in a private garden called Xuyuan, located in what is now Hongkou District in the northern part of Shanghai. In 1908, China’s first movie theater, the Hongkou Moving Shadow Play Theater, opened in Shanghai. [Sources: Chen Changye, Sixth Tone, June 22, 2017; chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

In 1897, an American came to Shanghai to show films made by the famous inventor Edison. In 1898, Edison sent his photographers to China and made the documentary film "China Honor Guard". In January 1902, movies were introduced in to Beijing with the display of the first film "Black People Eat Water Melon" and other comic short movies. In 1903, a Chinese student named Lin Zhusan came back from overseas with films and players and opened the history to show movies by the Chinese. In December 1907, Beijing Grand Theater completed its rebuilding and began to show movies. In the same year, the first real cinema, Ping'an Movie, was established by foreign investors at the Chang'an Avenue in Beijing.

Battle of Dingjunshan: the First Chinese Film

It was not until November 1905 that the Chinese shot their first film, The “Battle of Dingjunshan” (“Conquering Jun Mountain”). It was adapted from a Peking Opera of the same title by the Beijing Fengtai Photo Studio and Tan Xinpei, a renowned performer of Peking Opera. The shooting of the film marked the official birth of Chinese cinema. The film is a silent one and, according to requirements of silent movies, it only shot some action pictures such as "Asking for Fight", "Fighting with a Sword" and "Face to Face Fight ".[Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

The producer of the film is Ren Jingfeng, who had studied photography in Japan. He bought a manual camera and 14 sets of films from a German merchant for the film. He hired Liu Zhonglun as his cameraman. The film was produced outdoors for three days without transcript or background. Though it was very coarse, the film marked the beginning of the China film history. It is a precious material for the study of China film and Peking Opera.

The film consisted of a recording of Peking opera superstar Tan Xinpei dressed in the character Huang Zhong and singing some arie from the Peking opera of the same name. The play is a dramatised account of Battle of Mount Dingjun (A.D. 219) and based on an episode in the 14th-century historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms. The only print was destroyed in a fire in the late 1940s.

Beginning of the Chinese Film Industry

The Chinese film industry didn't begin until 1913 when Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan shot the first Chinese movie “The Difficult Couple” (1913). .The first sound film, “The Songstress, Red Peony” was released in 1931. It starred the then "film queen" Butterfly Hu (Hu Die in Chinese) and was produced by Star Studio, Shanghai's largest film production studio. Stars like Hu and Zhou Xuan were household names. [Source: Lixiao, China.org, January 17, 2004]

The first film studio in China, the Asia Film Company, was founded in 1909 in Shanghai by Benjamin Brodsky, an American filmmaker of Russian descent. It produced and released“The Difficult Couple” During the 1920s film technicians from the United States trained Chinese technicians in Shanghai, an early filmmaking center, and American influence continued to be felt there for the next two decades.

Zhang Shichuan set up the first Chinese-owned film production company in 1916. The first full-length feature film was “Yan Ruisheng”, released in 1921. which was a docudrama about the killing of a Shanghai courtesan, although it was too crude a film to ever be considered commercially successful. Since film was still in its earliest stages of development, most Chinese silent films at this time were only comic skits or operatic shorts, and training was minimal at a technical aspect due to this being a period of experimental film. The Mingxing Film Company, founded in 1922 in Shanghai, became the longest-running and most influential privately owned film company in the history of Chinese film. It produced numerous silent movies then switched to talkies (sound movies). [Source: Chen Changye, Sixth Tone, June 22, 2017; [Source: Wikipedia]

“Laborer’s Love" (1922), the earliest surviving complete Chinese film

“Laborer’s Love" (1922) is the earliest surviving complete Chinese film. In this short slapstick comedy, a carpenter-turned-fruit seller is in love with a doctor’s daughter and uses the tricks of his former trade to win her father’s approval. Features special effects and original Chinese-English intertitles. Draws a laugh from kids and grown-ups alike. [Christopher Rea]

First Generation of Chinese Film

The first couple of decades of film make in the early 20th century is referred to by some as the "First Generation" of Chinese film John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”: Film was “approached from an operatic stage perspective, with fixed-camera shooting, step-by-step descriptions of ordinary plots, and dominance of story over the performances of actors and actresses. Although by the end of the period (late 1920s) about one hundred directors were making films, two dominated (Zhang Shichuan [1890-1954] and Zheng Zhengqiu [1889-1935]), with a few others such as Ren Pengnian, Dan Duyu, Cheng Bugao, Bu Wanchang, Li Pingqian, Hong Shen, Yang Xiaozhong, Shao Zuiweng, and Sun Yu also in the limelight. [Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

“These filmmakers made the biggest contributions with the first short feature Nan fu nan qi (Husband and Wife in Misfortune, 1913), directed by Zheng Zhengqiu and Zhang Shichuan; first full-length feature, Yan ruisheng (1921), directed by Ren Pengnian; first sword-fight film, Huo shao hong lian si (Burning of the Red Lotus Temple, 1928), directed by Zhang Shichuan; and first sound feature, Ge nu hong mudan (The Sing-Song Girl, 1931), directed by Zhang Shichuan. These works were created under difficult circumstances, with simple and crude equipment and without training and experience.

“Family-oriented films that drew on the lives of urban residents in the lower social strata were popular until the late 1920s, when audiences tired of their unrealistic, shallow plots. Most dealt with love affairs, marriages, household situations, and ethical issues. Gradually, they were supplemented with films that exposed the grim and pressing issues facing China; the first of these were Sun Yu's Ye cao xian hua (Wild Flower, 1930) and Gu du chun meng (Spring Dream in an Ancient Capital, 1930). Others followed, such as Zheng Zhengqiu's Zi mei hua (Twin Sisters, 1934) and Wu Yonggang's Shen nu (The Goddess, 1934), both depicting the plight of suffering women, and those that resulted when the Left-wing Writers' League took an interest in film in 1931, such as Cheng Bugao's Kuang liu (Torrent, 1933), and Chun can (Spring Silkworms, 1933), and Cai Chusheng's Yu guang qu (The Life of Fishermen, 1934). The latter three films dealt with the bitter lives of peasants.

Cave of the Silken Web

“The Cave of the Silken Web” (Dan Duyu, 1927) is believed to be the first screen adaptation of "Journey to the West", one of the most enduring classics of Chinese literature. On their journey to India to procure Buddhist scriptures, pious monk Xuanzang and his three disciples Monkey, Pigsy, and Sandy are under constant threat from demons and malicious spirits. In this adaptation they are besieged by spider demons disguised as beautiful maidens. Besides the special effects-aided supernatural feats, Chinese silent star (and Dan's wife) Yin Mingzhu plays the beguiling spider queen.

Stories from “Journey to the West, particularly those involving the Monkey King (aka Sun Wukong), would prove to be an enduring motif in Chinese cinema, showing up in over 400 films over the decades. “Dan's The Cave of the Silken Web, once thought lost, was rediscovered in 2011 and preserved by the National Library of Norway. The artist and writer Krish Raghav wrote: “A lush, richly costumed silent film, Cave of the Silken Web is one of China’s earliest fantasy films. In 2016, “The Cave of the Silken Web" was shown at the Getty Center Museum Courtyard in Los Angeles to music by Yo Yo Ma's Silk Road Ensemble.

According to the South China Morning Post: “In the film, Tang Sanzang, (Xuangzang) a pilgrim monk entrusted by a Tang-dynasty emperor to find some sacred Buddhist texts, ends up trapped in the Cave of the Seven Spiders, who want to eat his flesh to become immortal. The monk is later saved by his disciple Sun Wukong, or the Monkey King. First screened in Oslo in 1929, the copy found in Norway features subtitles in Chinese and Norwegian. “In 1967, the legendary Hong Kong film studio Shaw Brothers made another film of the same name, based on the same episode of Journey to the West.” Norway gave the film to China. [Source:South China Morning Post, April 15, 2014]

“The Cave of the Silken Web” (Dan Duyu, 1927)

Shanghai and the Golden Age of Chinese Film

Shanghai hosted an exciting film industry during the swinging 1930s, when the the port city was filled with foreigners and was a major hub for freshly imported jazz. Classics from the Shanghai Golden age include “New Woman” (1934), a silent film directed by Cai Chusheng and starring Rian Lingyu, the “Chinese Garbo” ; and “Song of Midnight” (1935), a Chinese version of “Phantom of the Opera”, directed the macabre Ma-Xu Weibang.

Shanghai was regarded as the Hollywood of the East in the 1920s. The people that lived there loved to go to movies and they could enjoy watching them at wonderful Art Deco movie houses. One film club founder told the Los Angeles Times, “Ninety percent of film back then reflected life n Shanghai. There was no other Chinese city capable of representing modern life.” Great figures from Shanghai cinema include the great actress Shangguan Yunzhu, revered director Fei Mu. The prominence of Taiwanese and Hong Kong figures like director Hou Hsiao-hsien and singer/actress Rebecca Pang illustrate how much of Shanghai’s creative spirit migrated to Taipei and Hong Kong after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz wrote in China Beat: “Films by pioneering Chinese directors of the 1920s and 1930s still dazzle, with their opulent sets, the metropolitan glamour of Shanghai, not to speak of their melodramatic stories of love and distress, passion and agony,” “Imagine, for example, the following opening shots: The camera zooms in on the supple thighs of a young woman. A few seconds later, you — the viewer’ see her charming smile. She is wearing a simple short sleeved shirt, both arms exposed, and clad in shorts with one of the seams torn. In full view now, you are able to admire her slender body. She is in a playful mood. Such are the opening shots of Sun Yu’s 1931 film Wild Rose (Ye meigui), set in an idyllic countryside. But this dream world will not last; misfortune will soon befall the female protagonist and the man she loves. Painful separation seems inevitable. Will the couple eventually reunite? What will lead them back together? ”[Source:Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz, China Beat, August 30, 2010]

The film industry in Shanghai was hit hard after Japanese forces invaded the Republic of China in 1937.The Shanghai film scene collapsed when the Communists came to power in 1949. Many film people fled the country and ended up in Hong Kong, and launched the film industry there.

Well-known figures in the Shanghai 1930s film scene included leftwing director Cai Chusheng, soft-film advocate Liu Na’ou and dramatist Hong Shen. Among lesser-known but influential figures were the critic and screenwriter Zheng Boqi, the president of the Chinese Institute of Mentalism Yu Pingke, art critic and economist Gao Changhong, propaganda theorist Zhu Yingpeng, and Japanese literary scholar Kuriyagawa Hakuson. In the book “Shanghai Filmmaking” (Brill, 2014), Huang Xuelei gives readers an intimate, detailed, behind-the-scenes tour of the world of early Chinese cinema. According to the book’s publisher: She paints a nuanced picture of the Mingxing Motion Picture Company, the leading Chinese film studio in the 1920s and 1930s, and argues that Shanghai filmmaking involved a series of border-crossing practices. Shanghai filmmaking developed in a matrix of global cultural production and distribution, and interacted closely with print culture and theatre.

Old Chinese Movie Magazines

Oscar Holland wrote in CNN: If Hollywood's golden era can be understood through magazines like Silver Screen and Photoplay, then China's early film industry can also be viewed through the most popular movie publications of their day.“For film critic and historian, Paul Fonoroff, this means studying the elaborate, colorful pages of titles like Movie Weekly, Silver Flower Monthly and the supremely popular Chin-Chin Screen. [Source: Oscar Holland, CNN, December 9, 2018]

“China's film industry, like America's, flourished from the early 1920s with the arrival of new technology and the subsequent end of the silent era. This new age of glamour was epitomized by visually striking publications — from academic journals to tabloid-style rags — that unpicked films and obsessed over their stars. Articles spanned news and gossip, as well as script-writing, reviews and film theory, according to Fonoroff, who has recently published a book based on his enormous personal collection of Chinese magazines, fanzines, souvenir booklets and one-off publications.

Chen Zhi Gong in

Swordswoman of Huangjiang"There were some more scholarly or politically-oriented journals, but they were, for the most part, entertainment magazines," he said in a phone interview. "Despite the covers, the articles inside were actually (often) quite serious. But then there's all those fun things too — who's sleeping with who, and the politics of it all. A lot of these magazines and studios were controlled by people who were part of the underground Communist Party," he added. "So they were getting in a leftist message."

US films were popular in China, so the magazines' covers often boasted images of the Hollywood stars of the time — figures like Elizabeth Taylor, Ingrid Bergman, Esther Williams and Fred Astaire. But early Chinese starlets like Ruan Lingyu, whose 1935 suicide captivated the country's media, and Hu Die, star of some of China's first sound films, also regularly featured. Mao Zedong's future wife Jiang Qing can even be found in Fonoroff's collection as she promoted her film "Fight for Freedom" under the stage name Lan Ping.

“And while the magazines' beaming cover stars followed in the tradition of their Hollywood counterparts ("the calling card was a pretty girl," said Fonoroff), their designs carry a distinct aesthetic. "I would say to a large part they're in the same mold as Hollywood magazines — but there's a major exception," Fonoroff explained. "Hollywood magazine invariably had a photograph of a movie star on the cover — that was the chief selling point.

Chinese Films from the Early 1930s

“Spring Dream in the Old Capital” (directed by Sun Yu, 1930), according to Xueting Christine Ni, depicts the lives of ordinary people — street peddlers, poor scholars, and young revolutionaries — and reflects the culturally progressive political climate of that pre-War, post-May the 4th era. According to Radii: Director Sun Yu was a core member of one of the three major production companies in Shanghai during this era, the Lianhua Film Company. His silent films during the period — like 1930’s Spring Dream in the Old Capital, 1933’s Wild Flowers and 1933’s Little Toys — established him as a leading storyteller at the time. Sun left Shanghai after the Japanese invasion in 1937, and continued to make films after the Chinese Civil War, though his career stalled after Mao Zedong personally denounced Sun’s 1950 big-budget historical drama The Life of Wu Xun. [Source: Radii, 2021]

“Two Stars in the Milky Way” (directed by Dongshan Shi as Tomsie Sze, 1931) is about an actor who meets a singer while starring in a movie together. The singer, Li, falls in love with the actor only to discover that he is already married. Michael Berry, Professor of Contemporary Chinese Cultural Studies and Director of the Center for Chinese Studies, UCLA said: A curious film produced on the cusp of transition between silent cinema and sound cinema, Two Stars provides a tour through pop culture of the Republican-era Shanghai, from miniature golf and dance halls to cinema culture and art deco architecture. At the same time, the film probes the transition from tradition to modernity and the toll that transformation takes on the individual.

“Scenes of City Life” (directed by Yuan Muzhi, 1935) is one of the earliest talking feature films in China. It is known for being the directorial debut of actor Yuan Muzhi and for starring Lan Ping, better known as Jiang Qing, the future wife Mao Zedong and leader of the Gang of Four. Linda C. Zhang wrote: Yuan Muzhi’s film addresses not only the contradictions of urban life in Shanghai during the “golden age” of Shanghai cinema, but also the apparatus of film itself. It opens with various montage sequences and documentary-like footage of Shanghai, through the device of the “peep show.” Watch it for a cameo of the director himself, as well as a “movie-in-a-movie” moment featuring a short animation by the Wan Brothers!

New Film Movement and Leftist Film-Making in the 1930s

1935 farmer film Leftist film-making began in the 1930s. The New Film Movement featured works on social issues that courageously exposed the grim and pressing problems in China at that time. Screenwriters and directors stepped out of the narrow confines of family ethics and tackled issues that affected Chinese society at large. "Three Modern Girls", written by Tian Han and directed by Pu Wancang, was the representative of the movement. The film depicts a young man and three modern girls choosing varied lives indicating the relations between the age and personal fates. When launched in 1933, the film won full of applauses. Later Xia Yan, Sun Yu, Cai Chusheng, Shen Xiling, Wu Yonggang and Yuan Muzhi created a batch of films combining their anxiety about the society, their concerns about the masses and their origination in arts, such as "Broad Road", "The Goddess", "Street Angel" and "Crossroads". [Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

In the 1930s the introduction of sound technology occurred in tandem with the politicization of the film world in the wake of the bombing of Shanghai in 1932. Major figures in the leftwing film movement that emerged at this time were the director Cai Chusheng and the writers Tian Han, Xia Yan, and Zheng Boqi. Resistance against imperialism and feudalism were central themes. Weihing Bao describes leftwing cinema as a radical movement that marshaled the tenets of modernist aesthetics toward the ends of mass politics. [Source: Reviewed by Jean Ma, Stanford University, Jean Ma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, February, 2016; Book: “Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915-1945" by Weihong Bao (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)]

During 1933 and 1935, the left-wing movement in filmmaking was introduced to Shanghai and flourished. Torrents (1933) (Kuangliu in Chinese), directed by Xia Yan and Cheng Bugao and produced by the Star Studio, was the first film of this genre. Many famed directors came to the fore and made outstanding contributions in art and literature, such as Yuan Muzhi's Street Angel (1937) and Shen Xiling's Crossroad (1937). They brought the darker, seamier side of society to light and gave expression to the wishes of the people to pursue their dreams as well as rebel against imperialism and feudalism. A great variety of artistic images were born and a number of acclaimed actors and actresses emerged. Butterfly Hu, Zhao Dan, Zhou Xuan and Shu Xiuwen were amongst them. [Source: Lixiao, China.org, January 17, 2004]

Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz wrote in China Beat.“The intertwined themes of romance and revolution have recurred throughout the history of Chinese filmmaking and continue to have remarkable appeal today. Early Chinese silent-era filmmaking produced a good number of such stories and audiences never tired of them. Women took center stage — from the innocent Xiao Feng (played effectively by Wang Renmei) in Wild Rose (1931) to the seductress Li Huilan (played nicely by Xue Lingxian), a woman who seeks men for pleasure and money in A Dream in Pink (Fenhongse de meng, 1932, d. Cai Chusheng). The viewer first marvels at how the materialistic new woman Zhang Tao (played by the vivacious Li Lili) ultimately repents in the film National Pride (Guo feng, 1935, d. Zhu Shilin), and then feels emotional distress as Xiao Mao (played again by Wang Renmei) loses her only brother to malnutrition in Cai Chusheng’s famous Song of the Fisherman (Yu guang qu, 1935).” [Source:Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz, China Beat, August 30, 2010; Yap Soo Ei and Ji Xing were graduate students in the Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore (NUS). Nicolai Volland and Yang Lijun teach Chinese Studies at NUS, and Paul Pickowicz is professor of Chinese History at the University of California, San Diego]

The City as an Evil Place in Shanghai Films From the 1920s and 30s

1935 education film Oscar Holland wrote in CNN: Cinemas were largely an urban phenomenon in Republican-era China. The country's early movie industry revolved around Shanghai, although magazines appeared in smaller cities like Kunming and Wuhan. Movie-going was also a working-class activity, not strictly an elite one, as reflected in the variety of magazines and their sometimes sizable print runs. In the 1930s, one of the most popular movie publications, Diansheng (or "Electric Sound," although it was known in English as Movietone), produced around 10,000 copies a week, by Fonoroff's estimates. [Source: Oscar Holland, CNN, December 9, 2018]

Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz wrote in China Beat: Another "theme that caught our attention is the depiction of the big metropolis, that is, Shanghai modern and its irresistible allure. Take "A Dream in Pink", complete with a street lined with tall trees, an art deco interior, women in bright qipaos dancing in the marbled mansions of the French Concession. Similar images appear on screen in almost all the films we viewed. It seems that many movies from the 1930s were bathing in the glitz and glamour of the modern metropolis.” [Source:Yap Soo Ei, Ji Xing, Nicolai Volland, Yang Lijun, and Paul Pickowicz, China Beat, August 30, 2010]

“The city-on-screen, however, is highly paradoxical. Almost invariably the modern metropolis is revealed to be as evil as it is alluring. Underneath its bright and modern veneer is a moral abyss which causes people — the young in particular — to lose their moral bearings and fall into a degraded state. In National Pride, Zhang Lan (whose name, Orchid, implies nobility and virtue) learns that big city culture will destroy young people, while rustic life and self-discipline will purify their minds. Propaganda is a conspicuous component of National Pride, which was produced for the Guomindang’s New Life Movement, but it is interesting to note that the demonization of the modern city is a common theme in Chinese films of the 1930s, including so-called leftist works. In this respect, they resonate (intentional or unintentionally) with cultural traditions that tend to favor the countryside over the city, the rural over the urban. Literature since the late Qing has depicted the prosperity of Shanghai as a symbol of hypocrisy. Ugly and immoral phenomena, including prostitution, deception, and greed, are said to corrode the simple and modest lifestyles of the past.”

“The danger of the metropolis is often attributed in these films to spiritual pollution — corrupt culture (especially Western culture) imported from abroad. Once again, we have a theme that feels very current. How to resist this pollution? How does its harm manifest itself? The answers to these questions vividly unfold in such films as "A Dream in Pink", where the screen vamp Li Huilan literally embodies the attractions and dangers of Western culture and ultimately stands in for the metropolis itself. She is independent, fashionable and charming. She never waits for men. She talks about love but never relies on love. At the end of the film, she deserts her lover (who has divorced his lovely wife in favor of the vamp) and leaves with another man. She is a female figure who differs radically from what is often imagined to be the stock traditional Chinese woman. Director Cai Chusheng thus poses poignant questions. Is Western culture suitable for China? Is a city (like Shanghai) a safe place to be? What is substantial and good in the city.

“Despite its potentially corrupting influence, the modern city retains its magnetic powers of attraction, a pull that was obviously well understood by the directors and permeates the films. Young women from the rural areas, for example, cannot help being fascinated by the modern, educated ladies on display in such films as "Boatman’s Daughter". And in a film like "National Pride", which explicitly devalues the city and Western culture, extravagant and luxurious city life is omnipresent on screen and seems to undermine the original anti-urban messages. Is this another example of unintended consequences? Similarly, while the countryside might appear idyllic (in "Song of the Fisherman" and other works), it is almost always shown to contain violent and life-negating elements (in "Wild Rose" for instance) and other negative forces. This paradox of the city, its allure and glamour alongside its pernicious influences, was clearly one of the powerful riddles that attracted Chinese films audiences of the 1930s. Eighty years later, this attraction has lost little of its allure.”

“Mulan Enlists in the Army”

Influence of 1937 Japanese Invasion on Chinese Cinema

Sole Island Movies refer to a batch of movies made in Shanghai, an isolated region, after the Japanese invaded China. In the 1930s, a group of filmmakers produced an enormous number of commercial films in Shanghai implicating their anger, including “Shouts and Resistance under Cruel Japanese Oppression”. Each year an average of 60 movies were produced. The invasion of the Japanese into China after the September 18 Incident in 1931 aroused the indignation of the Chinese people. As the national anthem says, "The people of China are in a most critical time. Everyone must roar his defiance." Movies with a spirit of fighting against imperialism and the Japanese aggression became the sound of a bugle, loud and encouraging. Judging from their content and ideological features, fine movies about the fight against imperialism and Japanese aggression can be divided into three stages. The first stage went from September 1931 to July 1937. Movies made during this stage mainly reflect the disasters brought about by the invasion and the awakening of the Chinese people. The screenwriters and directors concentrated their efforts on encouraging and arousing the enthusiasm of people in the struggle against Japanese aggression. [Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

In a review of the book “Fiery Cinema”, Jean Ma wrote: With the full-scale invasion of Shanghai by the Japanese in 1937 and the relocation of the Nationalist government to Chongqing came a reorientation of cinema toward national defense and the explicit aim of propaganda. Yet the turn to propaganda marks not a rupture from an earlier era of entertainment, but rather a continuation in a new key of the media aesthetics and spectatorial modes of prewar cinema. Thus in the post-1937 cinema of agitation, the earlier dispositifs of resonance and transparency return with a charged significance. [Source: Reviewed by Jean Ma, Stanford University, Jean Ma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, February, 2016; Book: “Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915-1945" by Weihong Bao (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)]

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937 marked the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. As the event reverberated through Chinese media — relayed in news reportage and newsreels, mediated in poetry and spoken drama — it “initiated a national experience of the intensity of now” and launched the “singular time” of the War of Resistance. The westward migration through the hinterlands to Chongqing entailed a massive diffusion of these networks through space, penetrating regions beyond the urban center of Shanghai and reaching the rural masses. The geographic relocation of the center of power and cultural production contributed to the synchronization of the country within a singular time of emergency. Yet it also raised questions of how to reach new audiences composed of diverse demographics and identities, thus provoking reconsiderations of film and its aesthetics. In this context, wireless technology emerged as a master metaphor — for a radiating media network that aspired to instantaneity and coverage, also for the power of propaganda as a crucial instrument in a “war of nerves” waged both on land and in the ether. Along these lines, cinema too was reconceived as a “mobile art leaping in the air,” refitted as such by means of mobile projection units and multimedia formats of exhibition.

“Wartime Chongqing cinema responded to “the urgency of functionalizing art for immediate mass action,” and its politicality was inflected by the complex history of propaganda in China. Propaganda was tightly interwoven with longstanding trajectories of education and commercial publicity. As Bao points out, 20,000 bombs were dropped by enemy planes on Chongqing between 1938 and 1943; in this war of nerves, the cinema of agitation “provided the counterpart of such bombing in reconstructing space and time through a radical reorientation of mass media.” Fire assumes a new set of meanings as a metonymy of destructive violence. But in films like “Baptism by Fire”, “Paradise on Orphan Island”, and “Princess Iron Fan” (the first feature-length Chinese animation), the motif of fires assumes an even broader range of connotations: the furnaces of industry and reconstruction, the energy of the crowd, the spreading of information, the plasticity of the animated image. Reigniting “the promise of a radical spectatorship achieved through physical thrill and psychosomatic immediacy,” the fiery cinema of resistance recalls a history of popular genre cinema, breaking down divisions between leftwing and entertainment cinema. In the ideal scenario of propaganda cinema, Bao writes, “media stimuli transform into the spectator’s immediate action, annihilating the spatial demarcation between the screen and the audience. What brought about this optical result if not the chivalric martial arts body in fiery films?”

A representative movie in the period is “Hua Mu Lan” (1939) is also known as “Mulan Enlists in the Army”, which tells the story about an ancient girl Mulan. In the story, the smart but clumsy tomboy daughter of a once-great general, disguises herself as a boy and enlists in the Chinese army to save her ailing father. The film won acclaims and continued to play for 85 days. According to Christopher Rea:, recruits the legendary woman warrior to the cause of resistance against Japan. This allegorical costume drama, a musical starring Cantonese actress Nancy Chan (Chen Yunshang) in her first Mandarin-language role, was a sensation across a divided China. Packing in crowds in semi-occupied Shanghai, Japanese-controlled Nanking, and Nationalist Chungking, the film was also literally burned in the streets by agitators who considered the filmmakers to be collaborationist traitors.

Classic Chinese Films of the Late 1930s

“Street Angel” (directed by Yuan Muzhi, 1937) is viewed as one the great cinematic efforts of China’s Golden Age of cinema. It stars legendary actress Zhou Xuan, and revolves around the problems of a group of young people struggling to become financially independent. Xueting According to Christopher Rea: A teenager flees war in northeast China” Japan’s 1931 invasion) and ends up working as a songstress in a restaurant in Shanghai. When her foster parents decide to sell her to a thug, she runs away with her boyfriend from across the lane. Features two hit songs by Zhou Xuan and charming performances by her and co-star Zhao Dan, one of the era’s best comic actors. Another genre-defying tragicomedy focused on the lives of the lower classes.

Street Angels

Christine Ni wrote: This early sound film is a masterpiece of romantic socialist realist cinema that recent film directors have revisited in their works, because post-Communist 21st-century China is increasingly showing its capitalist colors and with this, generating a similar rich/poor divide and conflict of aspirations that the Republican era of Street Angel once did. The absolutely crippling Sino-Japanese War was China’s WWII, and like the impact of the World Wars elsewhere around the world, it’s still felt today.

“Crossroads” (directed by Shen Xiling, 1937) is a drama comedy about four friends caught up and separated during strikes in Shanghai. It is known for containing direct references to the war with Japan and supporting leftist politics. Linda C. Zhang: A romantic comedy that tells a charming tale of neighborly dispute and romance, with deeper commentary on remaining youthful and non-cynical during less fortunate times. Inspired many other contemporary movies with similar romance set-ups, such as Shanghai Blues. [Source: Radii, 2021]

Comedies and Horror Movies in 1930s and 40s

Costume dramas, love movies, comedies, dance movies, exploratory movies and ghost movies were also popular at the time. Compared with the commercial movies produced in the 1920s, they were more mature commercial filmmakers in China, and laid foundation and provided reference for the later development of Chinese commercial movies.

“Song at Midnight” (1937) is a horror-musical! According to Christopher Rea: Phantom of the Opera” (1925) inspired Song at Midnight’s premise and the genre atmospherics, but this film has a lot more going on, including a convoluted revolutionary backstory for the maimed “phantom” and a violent love triangle. The marketing campaign claimed that the film scared a child to death. [You Tube video: youtube.com ]

“Long Live the Missus!” (1947) is a Chinese take on the screwball comedy, featuring an over-eager-to-please upper class housewife, her unreliable spouse, and a glamorous seductress in Civil War-era Shanghai. Shangguan Yunzhu steals the show as the homewrecker “Mimi,” as does Shi Hui as the hilarious Old Mr. Chen. The tightly-plotted screenplay is by Eileen Chang, one of modern China’s most celebrated writers and author of the story “Lust, Caution.”

“Wanderings of Three-Hairs the Orphan” (1949) features Sanmao (Three-Hairs), a comic strip character come to life in this film, which strings together several episodes from the original work’s depiction of the life of a street urchin in Shanghai, culminating in a bedlam ballroom sequence in a mansion. Working at an historical turning point, the filmmakers tacked on the victory parade ending after the People’s Liberation Army entered Shanghai in May 1949. [You Tube video: youtube.com ]

“Long Live the Missus!” (1947)

Xu Zhuodai (1880-1958) was known as the Charlie Chaplin of China. Christopher Rea wrote: A comic dynamo who made Shanghai laugh through the tumultuous decades of the pre-Mao era, Xu was a popular and prolific literary humorist who styled himself variously as Master of the Broken Chamberpot Studio, Dr. Split-Crotch Pants, Dr. Hairy Li, and Old Man Soy Sauce. He was also an entrepreneur who founded gymnastics academies, theater troupes, film companies, magazines, and a home condiments business. He wrote and acted in stage comedies and slapstick films, compiled joke books, penned humorous advice columns, dabbled in parodic verse, and wrote innumerable works of comic fiction. China’s Chaplin contains a selection of Xu’s best stories and stage plays (plus a smattering of jokes) that will answer the questions that keep you up at night. What is a father’s duty when he and his son are courting the same prostitute? What ingenious method might save the world from economic crisis after a world war? Who is Shanghai’s most outrageous grandmother? What is the best revenge against plagiarists, thieves, landlords, or spouses? And why should you never, never, never pull a hair from a horse’s tail? [Book “China’s Chaplin: Comic Stories and Farces” by Xu Zhuodai, translated and with an introduction by Christopher Rea ( Cornell East Asia Series, 2019]

Second Generation of Chinese Film

John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”: With the advent of the 1930s, film changed from functioning solely as entertainment to reflecting social life realistically. Chinese filmmakers also began to grasp the basic law of film, to move beyond the limits of the stage, and began producing modern dramatic films with suspenseful plots and performances that favored realism over stylization. [Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

“This progressive period lasted until the late 1940s, nourishing important directors such as Cai Chusheng, Wu Yonggang, Fei Mu, Sun Yu, and Zheng Junli, and actors and actresses such as Ruan Lingyu, Hu Die, Jin Yan, and Zhao Dan. Responsible for the biggest box-office draws of both the 1930s (The Life of Fishermen) and the 1940s Yi jiang chun shui xiang dong liu (The Spring River Flows East, 1947), Cai Chusheng made films that were well knit, rich in connotation, and broad in social background. Among Wu Yonggang's (1910-1935) twenty-seven films was The Goddess, a classic that starred Ruan Lingyu, the first film actress to win extensive public praise, who performed in twenty-nine movies in her short twenty-five-year lifetime. Hu Die was known for her leading role in the first sound movie and for playing dual roles in Twin Sisters, while Jin Yan, called the emperor of Chinese cinema in the 1930s, usually portrayed intellectuals.

“The Second Generation came into prominence when the Japanese invaded China in 1937, and many of their films were associated with resistance and the fight against imperialism. From 1931 to 1937 films often reflected disasters brought about by the Japanese invasion, such as Sun Yu's Da lu (The Great Road, 1934) and Xu Xingzhi's Feng yun er nu (Sons and Daughters in Stormy Years, 1935); a second stage (July 1937 — August 1945) portrayed the heroism of the Chinese against Japanese aggression, as in Shi Dongshan's Bao wei wo men de tu di (Defend Our Nation, 1938), Ying Yunwei's Ba bai zhuang shi (Eight hundred heroes, 1938), and films of the Yan'an Cinema Troupe under the Chinese Communist Party leadership.

“Postwar movies until Mao's coming to power in 1949 both analyzed and reviewed the war and the reasons for victory and focused on the strife in ordinary people's lives as the Communist Party and Kuomintang battled for control of the government. The Spring River Flows East depicted wartime struggles of the people and the humiliations they faced in the postwar period, while other films such as Tang Xiaodan's Tian tang chun meng (Transient Joy in Heaven, 1947), Shen Fu's Wan jia deng huo (Lights of Myriad Families, 1948), and Zheng Junli's Wuya yu ma que (Crows and Sparrows, 1949) exposed other dark sides of society at the time.

Chinese Film in the 1940s

In the 1940s, on the eve of China's liberation, filmmaking was in a chaotic state and some profiteers seized the chance to shoot blue films and scary movies. However there were still some wonderful films being made thanks to the concerted efforts of conscientious filmmakers, who made classics such as Spring River Flows Eastward (1947) by Cai Chusheng and Zheng Junli, Crow and Sparrow (1949) by Chen Baichen and Zheng Junli and Light of Million Hopes (1948) by Shen Fu. These films had high artistic value in screenplay writing, directing, performance, cinematography, music, art design and other aspects. Filmmaking developed more quickly in the 1940s than it had in the 1930s. [Source: Lixiao, China.org, January 17, 2004)

After the victory of the Anti-Japanese War, China came into a relatively peaceful stage. In the post-war period, a number of outstanding films reflected the shift of people's minds and desires from war issues to inner feelings of ordinary people. These films were called the Heart Films. The films focused the camera lens at the ordinary people and the strife in their ordinary lives. They showed human nature and feelings and the complicated inner world of people with a true portrayal of the characters' daily lives as well as the national crises and social development.

Crows and Sparrows

The most outstanding films of the style are “Lights of Myriad Families”, directed by Shen Fu. The film seems placid and mild, but it is actually profound. It depicts the post-war life of the petty bourgeoisies in the Kuomintang-ruled area. Hu Zhiqing, the leading character, is an employee in a company. He is kind and upright and works with his heart and soul for the company. His wife Youlan manages the family affairs methodically. Beijing bankrupt in the rural area, Hu's mother and younger brother go to Shanghai and join the couple. The family runs into difficulties as its members increase, prices skyrocket, and the family members are at odds with each other. Later, Hu is fired and the family is in a hopeless situation. Contradictions and disturbances arise one after another. The film shows the circumstances of a family, but it is actually the society in miniature. Though there exist bitter discords among the family members, there are moments of love and mutual understandings. "We should try to survive," says the leading character at the end of the film. "Let's be closer to each other." His remark hints at the meaning of striving for existence through unity and struggle, making the film shine with ideological brilliance. [Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

Another film is “Transient Joy in Heaven”, directed by Tang Xiaodan, showing in a plain, true manner of the social life and the sufferings of the intellectuals, government employees and teachers in Shanghai in the post war period. Ding Jianhua, the leading character, an upright man, is an engineer who contributed to the Anti-Japanese War. After the victory, he dreams about a peaceful and happy life. When he returns to Shanghai from Chongqing with his wife, what waits for him is unemployment. He has no choice but to sell the design of a house he has drawn for himself and his family. In the end he and his family lead a wandering life in the street. Meanwhile, a man named Gong, who turns himself into a Kuomintang "underground activity worker", continues to ride roughshod over others. He drives the Ding family out of their house and builds a sumptuous residence on the site according to Ding Jianhua's design. The direction of the film's spearhead of criticism and sarcasm was obvious.

Classic Chinese Films of the 1940s

“Spring River Flows East” (1947), according to Christopher Rea, is a two-part, three-hankie weepie has been likened to Gone With the Wind — an epic story of love, lust, heroism and betrayal set against a war that divided a nation. Made during China’s Civil War, this high-budget film boasting China’s leading actors follows a devoted wife who struggles to keep her family together during eight years of war, only to suffer a crushing betrayal. [Youtube Videos “Part 1: “Eight Years of Separation and Chaos” youtube.com ; “Part 2: “Before and After the Dawn” youtube.com]

“Crows and Sparrows” (1949) is regarded as an all-time great Chinese classic. Several families in a Shanghai rowhouse face eviction by the Nationalist official and his kept woman, who have appropriated the building from its rightful owner and occupied the upstairs flat. In an era of open war, hyperinflation, and violence at home and work, time is running out for everyone — speculators, intellectuals, carpetbaggers, and ordinary citizens. A splendid piece of filmmaking, Crows features comic alchemy and three of the most memorable villains of early Chinese cinema.

“Unending Love“ (directed by Hu Sang, 1947) was written by the famous Chinese write Eileen Chang. Loosely based on the Charlotte Bronte classic “Jane Eyre”, it is unique in that it took feminist politics as its focus, during a time when patriotic, polemical movies were the norm Xueting Christine Ni wrote: : Unlike the majority of post-War films of the ‘40s, which were quite polemical, Hu Sang’s feminist work Unending Love and Huang Zuolin’s satire “Barber Takes a Wife” (1947) were films that examined the impact of war in more complex and humanist ways.

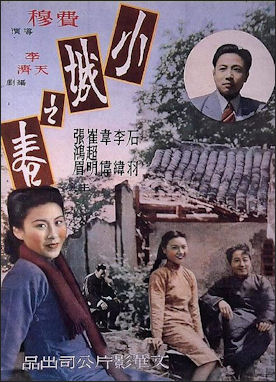

“Spring in a Small Town” by Fei Mu

“Spring in a Small Town” (directed by Fei Mu, 1948) is regarded as one of the best Chinese films ever made. A China-style psychological film, it depicts the feelings and inner world of three characters during a 10 day period in a southern small town. Seen a representative film made by Chinese intellectuals, the film is its remarkable artistic achievements, engrossing plots and its fusion of the personal and the historical, as well as the East and the West. The repressed emotional and sexual impulses of the main characters and the dying but irresistibly languid and romantic small town in a nation about to undergo unprecedentedly momentous change are all articulated in a language that is part literati poetry of Tang Dynasty and part Freudian unconscious.

According to Christopher Rea: Hailed as the finest Chinese film of all time, this intimate work of cinematic poetry shows five people struggling to rebuild their lives in the aftermath of a war. A married woman’s humdrum life in a small town changes when her former sweetheart returns after a decade’s absence to visit his old friend, her ailing husband. Her voiceover creates a gripping psychological drama, even as Fei Mu’s lyrical cinematography shows people hesitating at a moment of uncertainty, amidst an environment of ruins.

“Spring in a Small Town” was described by UCLA’s Michael Berry an “eternal masterpiece of post-war devastation and desolation.” According to Radii: This film “captures one of several crucial inflection points in Chinese history, paralleling the development of its cinema: the turbulent period following Japanese invasion in 1937. The film paints a very human portrait of a small town decimated by the second Sino-Japanese War, documenting the traumas that would create the foundation for post-WWII conflicts and the ultimate establishment of a modern, Communist-controlled nation-state in 1949. Xueting Christine Ni said: Films like Fei Mu’s Spring in a Small Town and Shen Fu’s Myriad of Lights (1948), which explore the post-War socialist collective, provide an insight into why Chinese society turned towards Communism.

“Spring in a Small Town”

The female lead, played by Wei Wei (now residing in Hong Kong) recounts her story in the Jia Zhangke “I Wish I Knew” about how Fei told her to help the then-inexperienced male lead feel more comfortable in his role by convincing him that she was really (off-screen) in love with him. It worked, but with unintended consequences — the young man was so smitten that he would not stop his pursuit even after the film shoot ended, resulting in her emigrating to Hong Kong just to be free of him. In telling this story, Jia intercuts between video of the actress remembering and sepia-toned black and white footage excerpted from Fei’s movie, fusing reality and artifice into something that falls magically in between.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021