TAIWANESE CINEMA

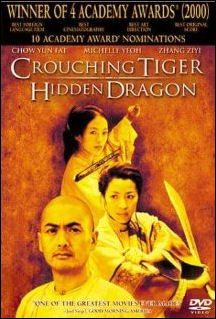

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

by Taiwanese director Ang Lee

(See separate article on him) Taiwanese cinema has operated in the shadow of Hong Kong, China, Japan and, more recently, South Korea and Thailand. Classics from the 1960s, “70s and “80s include the martial-arts blockbuster “A Touch of Zen”, made in Taiwan by the Hong Kong-based director King Hu. Among the recent noteworthy Taiwanese films the big box-office successes: the love story “Cape No. 7" and the gangster story “Monga,” as well as artsier fare like “The Fourth Portrait” and the Shakespeare-inspired (but not Shakespeare-worthy) trilogy “Juliets.”

“Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”by Taiwanese director Ang Lee is the highest-grossing foreign-language film in American history (Unless you count “The Passion of the Christ”). See separate article on Ang Lee

Book: “Taiwan Cinema A Contested Nation on Screen” by Guo-Juin Hong is the first study in English to cover its entire history of Taiwan cinema. Hong provides helpful insight into how Taiwan cinema is taught and studied by taking into account not only the auteurs of New Taiwan Cinema, but also the history of popular genre films before the 1980s. Chapters include: Tracing a Journeyman’s Electric Shadow: Healthy Realism, Cultural Policies, and Lee Hsing, 1964-1980; Interlude: Hou Hsiao-Hsien before Hou Hsiao-Hsien: Film Aesthetics in Transition, 1980-1982; A Time to Live, a Time to Die: New Taiwan Cinema and Its Vicissitudes, 1982-1986 ; Island of No Return: Cinematic Narration as Retrospection in Wang Tong’s Taiwan Trilogy and Beyond; Anywhere But Here: The Postcolonial City in Tsai Ming-Liang’s Taipei Trilogy.

Guo-Juin Hong is Andrew W. Mellon Associate Professor of Chinese Cultural Studies at Duke University. In 2011, his book “Taiwan Cinema: A Contested Nation on Screen” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) was published. The book is described as “A groundbreaking study of Taiwan cinema, this is the first English language book that covers its entire history. Hong has published articles on such topics as early Shanghai cinema, new Taiwan cinema, documentary film, and queer visual culture.

Taiwanese Cinema New Wave

Edward Yang, Hou Hsiao-Hsien and Tsai Ming-Liang led a movement known as the Taiwanese New Wave, or the New Taiwan Cinema, that began in in the 1980s and peaked and waned in the early 2000s. Hou’s “Millennium Mambo” and Tsai’s “What Time Is It Over There?” were both released in 2001. Edward Yang’s magnificent family drama “Yi Yi” was named the best film of 2000, in any language, by the National Society of Film Critics. The New York Times said it has Altman-like complexity and assurance.” "But the moment didn’t linger,” Mike Hale wrote in the New York Times. “Mr. Yang, who died in 2007, never made another movie. Mr. Hou and Mr. Tsai remained famous all over the festival circuit, while Mr. Lee made most of his movies in the United States. [Source: Mike Hale, New York Times, May 5, 2011]

Hale wrote: "”In Our Time”, a four-director omnibus considered one of the earliest examples of the New Taiwan Cinema; it was released in 1982, around the time of the first stirrings of political reform in what had been a repressive, totalitarian state. The second segment of that film, about a teenage girl and her interest in the college student who rents her family’s spare room, was Edward Yang’s debut as a writer and director. It’s a period piece, like many other 1980s Taiwan films, made when commenting directly on contemporary life or politics was a dangerous business. The girl’s older sister listens to the Beatles (“Hello Goodbye”) on her transistor radio, and the presence of twangy British and American pop on the soundtrack is another New Wave trope. “Our Time” has some style, but it’s a long way from Yang’s best work.

Hou Hsiao-Hsien is known for his long takes and wide-angle shots. Hale wrote, "By 1985 Mr. Hou’s fifth feature, “A Time to Live and a Time to Die” was a complete realization of the early New Wave style: the slow pace, the distant camera, the way the most dramatic or pertinent parts of the story are often conveyed indirectly, as anecdotes or passing remarks. Mr. Hou’s story, an autobiographical tale that begins shortly after the main character’s family is cut off from the mainland in 1949 by the Chinese civil war, is suffused with the feelings of dislocation and grief, of bewildering exile, that run through Taiwanese film. Its style is sufficiently pronounced that perfectly reasonable viewers can find it profoundly moving or profoundly slow and boring, but anyone should be able to appreciate Mr. Hou’s craftsmanship: a kind of meticulous fluidity that gives a sudden close-up tracking shot of the young protagonist at the end of the movie a joyful, kinetic charge.

Tsai first feature, the 1992 “Rebels of the Neon God”, a contemporary story of disaffected Taipei youth that’s rougher and more vital than his later work. (It is an obvious precursor to “Unknown Pleasures,” the breakthrough film of the Chinese director Jia Zhang-ke.)

“Flowers of Shanghai (1998)” is an acclaimed film adaptation by the Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien of the novel “The Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai” by Eileen Chang. Hou is a master of muted yet consuming affect, which is indelibly demonstrated in the scene in which Tony Leung is irrepressibly, though laconically, melancholic in the company of boisterous companions.

Lacking a famous director but packing in a lot of pleasure, guilty and otherwise, is Chang Yi’s 1985 “Kuei-Mei, a Woman”. Stylistically it’s of a piece with the other new wave films, and it shares their mood of intense nostalgia, but it’s resolutely traditional---or Hollywood-like---in its unabashed four-handkerchief, women’s-picture plot. Among the challenges surmounted by Kuei-Mei, a spinster from the mainland pressured into a bad marriage, are a gambling and philandering husband, an ungrateful stepdaughter, an evil boss and a typhoon.”Kuei-Mei, a Woman” is a classicist’s melodrama, a dry-eyed tear-jerker, because of its restrained direction and the impressively controlled, realistic star performance of Yang Huey-sian. When Kuei-Mei goes into labor in a gambling den while holding a kitchen knife to her husband’s throat, Ms. Yang shows an aplomb that would have done Joan Crawford proud.

Tsai Ming-liang the Artist

The Malaysian-born, Taiwan-based director Tsai Ming-liang is best known for art house films that depict the slow pace of ordinary lives. He won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival ( “Vive L’ Amour,” 1994) and Silver Bears from Berlin (“The River,” 1997; “The Wayward Cloud,” 2005) and was named Asian Filmmaker of the Year at the Busan festival in 2010. His acclaimed “What Time Is It Over There?” was released in 2001. He has also enjoyed some success as an installation and video artist. [Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, December 27, 2010]

Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop wrote in the New York Times: “As a filmmaker, Mr. Tsai has enjoyed critical acclaim, but commercial success still eludes him, particularly in his adopted country. “Taiwanese audiences don’t accept my movies because they don’t fit into the Hollywood mold,” he said. “In Europe, audiences are more receptive, I think because they have a different sense of aesthetic.” His films have often been criticized for their long takes of simple moments, like the six minutes devoted to a woman crying in “Vive L’ Amour.”

His works as an artist have included “Withering Flower,” a large installation inside an abandoned military bunker on the Taiwanese island of Kinmen with a towering statue of the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek placed where artillery would have been and openings in the walls obstructed by bandages; and “It’s a Dream,” an installation that consists of a video and a few rows of movie theater seats that mimic the atmosphere of an old cinema. “It’s a Dream” Tsai said represents a nostalgic view of his childhood when his grandmother would take him to the cinema in the small Malaysian town where he grew up.

Films of Edward Yang

“Life is a mixture of happy and sad things. Movies are so lifelike---that’s why we love them.” “Then who needs movies? Just stay home and live life.” “My uncle says we live three times as long since man invented movies.” “How can that be?” “It means movies give us twice what we get from daily life.” Dialogue from Edward Yang’s Yi Yi. [Source: filmlinc.com, November 2011]

Born in Shanghai in 1947, Edward Yang was still a toddler when his family, like some two million other Chinese citizens, emigrated from mainland China to Taiwan after the end of the Chinese Civil War. Not surprisingly, one of the richest themes in his films (as in those of his friend and contemporary Hou Hsiao-Hsien) would become the search for identity---personal, social and political---in the small island nation. But Yang’s work was equally concerned with such universal subjects as the longing for missed opportunities and the age-old conflicts between parents and children, his deeply rational mind (he came to filmmaking after studying computer science and applied physics) always striving to impose order on the irrational world of human experience. His untimely death in 2007 robbed world cinema of one of its greatest talents at the peak of his career. All the more tragically, only one of Yang’s features, the acclaimed Yi Yi, had managed to receive commercial distribution in the United States, where the director lived for much of his adult life.

Many regard “A Brighter Summer Day” as Yang’s masterpiece.

Edward Yang films from the 1990s:”A Confucian Confusion” (1994). With rapier wit, Yang observes the self-asorption of a gaggle of twenty-something urbanites in this panoramic satire of life in the material world of 1990s Taipei. “Mahjong” (1996). In this latter-day screwball farce set around a trendy night spot, Yang orchestrates the elaborate comings and goings of everyone from mob enforcers to a lovelorn Frenchwoman.

Edward Yang films from the 1980s: “That Day, on the Beach” (1982). Yang’s Antonioni-esque first feature (shot by Chris Doyle) is a visually and emotionally arresting melodrama about two old friends who meet after 13 years apart. “Taipei Story” (1985). A once-promising baseball prospect (played by Hou Hsiao-hsien!) moves in with his property developer girlfriend, in Yang’s most penetraying study of a changing Taiwan. “The Terrorizers” (1986). Yang’s most narratively intricate and formally audacious film begins with an early-morning police shootout and pulls in the enigmatic characters of a blocked novelist and her lab-technician husband.

“In Our Time” (1981) Edward Yang, Jim Tao, Ke Yizheng, Zhang Yi,. Yang’s plangent study of a teenage girl’s sexual awakening, “Expectations,” helped inaugurate the New Taiwan Cinema. “The Winter of 1905" (1982) Yu Wei-cheng. Legendary Hong Kong action director Tsui Hark as the great Chinese artist and Buddhist monk Li Shutong, a.k.a. Master Hong Yi, in a sensitively written story by Yang.

“Yi Yi” (2000). A middle-aged businessman and his family cope with crises in this irresistible, nuanced work of extraordinary synchronicity, empathy and narrative control.

Comeback of Taiwan Films

In November 2011, AFP reported: “After a slump of over a decade, Taiwanese movies are not only sweeping box offices at home but gaining awards and hit status overseas thanks to a new cohort of filmmakers.Taiwan's box-office revenues for home-grown films have set a new record of NT$1.5 billion (HK$375 million) this year - already triple the figure for the whole of last year and up a staggering 200-fold from 2001. [Source: AFP South China Morning Post, November 28, 2011]

Once best known for its arthouse films, the island has recently produced blockbusters with broad appeal thanks to themes that resonate with large swathes of the public. “Monga” , which topped Taiwan's box office last year and was screened at the Berlin film festival, portrays a brotherhood of five boys and touches on issues such as gang violence and teenage bullying. This year's Night Market Hero depicts street vendors standing up against developers, while Jump Ashin tells the true story of a struggling gymnast turned coach.

"Previous directors tackled profound issues such as destiny and history - issues that seemed distant to many," film critic Steven Tu said. Tu, curator of the Taipei film festival, also noted that the number of productions has picked up, with a new movie released as often as every two weeks, up from every three or four months a few years ago. "In the past, some directors might only get one shot at making a movie. Now, the market is bustling and new investors are coming in," he said.

Taiwan's Golden Horse awards... saw a record submission of 182 films, which organisers said reflected the renaissance of Chinese-language film and the island's rising cinematic clout. The biggest surprise this year was arguably author Ko Ching-teng's directorial debut, You are the Apple of My Eye, a teen romance that grossed NT$400 million in Taiwan. Ko was overjoyed by the film's success in Hong Kong, where it has raked in about US$7 million and is poised to become the best-selling Chinese-language film this year. "I truthfully and sincerely shot the story of my youth and I think that's why people ... find it moving," he said.

Nearly 20 Taiwanese films have scooped various awards at festivals in Asia, the United States, Europe and South America this year, according to the Government Information Office.Director Wei Te-sheng's epic Seediq Bale, about aboriginal hunters battling Japanese colonial power in the 1930s, was a contender for the prestigious Golden Lion award at the Venice film festival this year. It is scheduled to be released in the United States in February, and rights have been sold to Australia and New Zealand, as well as to European and South American countries.

New Taiwanese Films

Shelly Kraicer wrote in the Chinese Cinema Digest: “”Pinoy Sunday” (Taibei xingqitian) is Ho Wi Ding’s first feature, following his pair of prizewinning short films for Cannes (Respire / Hu Xi, 2005 and Summer Afternoon / Xia wu, 2008). Manuel (Epy Quizon) is a slick, fast talking Filipino guest worker in Taipei who imagines he’s a hit with the ladies. Dado (Bayani Agbayani), his chubby coworker, has a wife and daughter back home in the Philippines and a lover in Taipei. One day, dreaming of the good life back home, they spot a large, brand-new, abandoned red couch. A totem for their imagined future happiness, they determine to carry it across Taipei back to their suburban factory dormitory. The heart of the film is the pair’s absurd, quite funny, occasionally poignantly sad journey across the city.” [Source: Shelly Kraicer, Chinese Cinema Digest]

“This is a very accessible comedy, leavened with some subtle but pointed social commentary. Filipinos make up the largest ethnic minority of Taiwan’s little known migrant workforce. Ho sketches out their rich and vibrant subculture and, through them, gives us a fresh view of Taipei, from the outside looking in. The film if anything is a bit too light and comical, though. What is missing is an intensification of character and detail: the hard work that might give the audience a deepening understanding of these two wanderers, an opening that reveals things we weren’t first aware of. The film, true to the current demands of the Taiwanese film market, keeps its head firmly pointed in the direction of accessibility.”

“While it is immensely encouraging that Taiwanese filmmakers are rediscovering a local audience for their films, there is a discouraging flip side. The restrictions on how new Taiwanese films can address their audiences in this growing commercialized market seem more and more tight. A youthful ticket-buying audience needs to be cultivated: the films’ mode can’t venture too far from entertainment ; depth needs to be sacrificed for breezy vigour; and beauty often flattens into cuteness. Directors like Hou Chi-jan are struggling to to inject real substance into the new Taiwanese cute youth film model: his ambitious One Day (You yi tian, 2009) shows both some of the possibilities and the real difficulties in making it work.”

Shelly Kraicer wrote in the Chinese Cinema Digest: “ ”The Fourth Portrait”(Di is zhang hua) is Chung Mong-hong’s third feature, and the best Taiwanese film of 2010 that I’ve seen. Xiang is ten year boy whose father has just died. Left seemingly alone in the world, he is befriended by a series of unusual characters---a retired school janitor who is a brilliant story teller, a bumbling young thief---who introduce him to a picaresque series of adventures, some slightly perilous, others quite madcap, in southern Taiwan. When Xiang’s mother (played by the fine young Chinese actress Hao Lei) finally appears, it seems like Xiang can settle into a new family life, but her job in the sex trade, his oddly menacing stepfather, and rumors about a missing older brother unsettle his world in unpredictable directions.”

“The film’s tone and its visual design are both extraordinary. The latter brings some of Chung’s experience of filming commercials into art filmmaking. Chung forces the film towards vibrantly over-saturated colors and striking compositions that make an immediate impact. Far from the slight shock-stimulation of TV ads, however, Chung’s images speak, they resonate. They also disorient, slightly, but then embrace and generously reward careful viewing. Might this in some way evoke the point of view of little Xiang, who is seeing much of the strange outside world for the first time, and whose dramatic development occurs, at one level, through image design and identification? The film’s title comes from the four pictures Xiang creates, for portraits that illustrate different ways of understanding parts of his world. Some of the plot sags a bit towards---but never comes too close to---cliche in the film’s second half. And unfortunately, Leon Dai’s performance as the menacing stepfather is way over-the-top, showboating a scene that’s already excessively overwritten and threatening to upset the balance of an otherwise delicately structured film.

“But the other actors make up for it, in particular the astonishingly subtle and intense performance by young Bi Hsiao-hai as Xiang, a reliably vivid, technically impeccable King Shih-chieh as Xiang’s first guide, and mainland actress Hao Lei’s impressive way of inhabiting the potentially fascinating but underwritten role of Xiang’s mother. Chung Mong-hong gets better and better with each film, and might well be poised to become the Taiwan’s next internationally notable auteur-filmmaker.”

Seediq Bale

Wei Te-sheng's blockbuster “Seediq Bale”, re-titled “Warriors of the Rainbow: Seediq Bale”, was originally 4½ hours long but has been cut to shorter international versions. [Source: Shelly Kraicer, Chinese Cinema Digest]

After Wei's surprisingly and hugely successful first film “Cape No. 7" (Haijiao qihao, 2008), he had the chutzpah and the finances to embark on his dream project: an epic history of the 1930 revolt by the Seediq, a Taiwanese aboriginal tribe, against their Japanese colonial masters. First, a bit of background: Wei Te-sheng based his Taiwanese aboriginal epic on a Taiwanese graphic novel that described an extraordinary though little known historical event: the Wushe incident of 1930. During the fifty-year long Japanese occupation of Taiwan, the remnants of the aboriginal tribes who first settled the island lived in the central Taiwanese mountains. The Japanese colonial government restricted these tribes from practicing their traditional head hunting and facial tattooing, and deprived t hem of their lands and weapons. An uneasy peace came to a head in 1930, when tribal leader Mouna Rudo, a "hero of the tribe", or "Seediq Bale" organized six villages of the Seediq tribe to attack the Japanese occupation police on October 27 in Wushe village. Their carefully planned and executed rebellion resulted in the killing of 136 Japanese men and women. The rebellion lasted for fifty days, as Japan sent police and army reinforcements to crush the aboriginal fighters. Eventually, the Japanese resorted to dropping poison gas on the rebels from aircraft. The rebellion took on an epic -- and desperate -- aspect of a 20th century Trojan siege. Seediq heroes fought to the death, while their family members were instructed to commit suicide in order to escape capture and humiliation.

Wei Te-sheng's original version of the film is split into two parts: the first sets the scene, outlining complicated internecine tribal rivalries, the arrival of the Japanese, social conditions of the occupation, the organization of the rebellion, and the Wushe incident itself. This section takes time to delineate a complex set of characters and the full range of their responses to Japanese occupation: from indifference to commercial cooperation (here we see the film's few glimpses of Han Chinese) to strained collaboration and cultural co-optation. The two most fascinating "middle" characters in the film are Seediqs who have become Japanese government policemen: they have assimilated into Japanese culture and still retain their own sense of aboriginal identity. The Seediq themselves retreat up the mountains, sink into alcoholism, and bridle under harsh Japanese rule. The Japanese themselves in the film have a range of colonial identities, from harsh racists through ambivalent educators to respectful observers of Seediq culture. Some of the Seediq become resigned to defeated subservience and survival, others, like the film's hero Mouna Rudo, quietly organize rebellion, while hot headed younger warriors want immediate action. Wei Te-sheng has ample resources at his disposal to assemble and mobilize all these different elements; and his even larger ambition is to depict the complexity, the moral ambiguity, and the impossibly difficult life or death choices that these communities have to make when facing threats of violence and annihilation.

There are clear weaknesses in the film: the characterizations are often flat; dialogue can sink, for large stretches of time, to mere expository recitations or repeated, stentorian heroic declarations. The unfortunately trite musical score unnecessarily italicizes (and thereby flattens) the rich emotional underpinnings of the story. The film relies on a certain amount of CGI to create its lush forest and mountain settings, and the effects are frequently, obviously inadequate. The mise-en-scène too often sports a kind of manga aesthetic (betraying its origins in Wei's memories of the original comic book, perhaps that results in brash, unsubtle compositions forcing a flat, pumped up "heroic" aesthetic on material that needs more varied visual treatment. This is also largely a men's film: Seediq and Japanese women are relegated to background, stereotypical roles, as largely passive observers.

But despite these flaws, the film has a visceral power, a plastic and supple rhythm that supplies substantial forward momentum and a confidence in its ability to tell complicated, multi-centred narratives. This is most evident in Wei's great set piece, the Wushe attack itself, which comes at the end of the first section. The second section is another film entirely: it absolutely unflinchingly, with real courage, delves into the darkest realms of war crimes, terrorism, mass suicide, cultural annihilation, and genocide. And gives its audience no quarter: we are forced to confront actions of the "heroes" -- with whom we have learned passionately to identify with -- that, in other, more "normal" contexts, might seem horrifyingly cultlike, sadistic, brutal. If Seediq Bale's second section had been shaped with the clear logic and focus of the first, it would have even more power. It is episodic, though, and amounts to a relentless accumulation of details of horribly violent acts (the structure is something like a theme and variations, though without any sense of forward movement). This piling up of horror after horror can be more wearying than morally and emotionally engaging for an audience. We are somewhere on the boundary between conceptual idea-based cinema and narrative cinema, and I'm not sure that Wei and his team have made the structural choices necessary to transform this section from the former to the latter. But Wei's deeper meaning is clear: in the most extreme situations, in which the spiritual life of a community, the survival of an entire society is being brutally extinguished, the normal categories of morality totter and sometimes collapse. Confronting a choice between either life without meaning or non-existence, what must a community do? This is a question that has, unsurprisingly, hit a nerve with Taiwanese audiences, who have flocked in huge numbers to see a film that may subconsciously address, in certain oblique ways, their own underlying existential anxieties.

Seediq Bale Row

Seediq Bale, Taiwan's most expensive film at $24.3m, is an account of the Wushe Incident, the 1930 uprising against colonial Japanese forces. No doubt the subject matter has enhanced the film-makers' sensitivities. A diplomatic row has broken out after the Venice film festival listed the originating country of the Wei Te-Sheng-directed film as "China and Taiwan". A protest has been filed by Taiwan's Government Information Office, as well as the production company ARS. Jimmy Huang, producer of Seediq Bale, said: "It's a pure Taiwan-made film and not a film made by Taiwan in cooperation with China." [Source: The Guardian August 1, 2011]

There has been a history of the national status of a film becoming part of the diplomatic interchange. Similar protests emerged when Ang Lee's Lust, Caution was listed under "Taiwan, China" at Venice in 2007. In 2010, the Shanghai film festival was forced to cancel plans for a Taipei Film Week after the Taiwanese organisers showed concern that films be described as from "Taiwan, China"---in effect, implying Taiwan is part of China, rather than an independent entity.

It's possible the "China" may have arisen after the participation of Hong Kong film-maker John Woo as executive producer. Woo is overseeing an "international cut", drawn from the film's two-part, four-and-a-half-hour running time.

Taiwanese Documentary Film

“Documenting Taiwan on Film: Issues and Methods in New Documentaries” edited by Sylvia Li-chun Lin and Tze-lan Deborah Sang (Routledge) is the first book-length study in English on Taiwanese nonfiction film. A promo for the book reads: Since the lifting of martial law, documentary has witnessed a revival in Taiwan, with increasing numbers of young, independent filmmakers covering a wide range of subject matter. These documentaries capture images of Taiwan in its transformation from an agricultural island to a capitalist economy in the global market, as well as from an authoritarian system to democracy. What make these documentaries a unique subject of academic inquiry lies not only in their exploration of local Taiwanese issues but, more importantly, in the contribution they make to the field of nonfiction film studies. As the former third-world countries and Soviet bloc begin to re-examine their past and document social changes on film, the case of Taiwan will undoubtedly become a valuable source of comparison and inspiration.

Table of Contents (chapters): 1) Introduction Tze-lan D. Sang and Sylvia Li-chun Lin; 2) Re/Making Histories: On Historical Documentary Film and Taiwan: A People’s History Daw-Ming Lee; 3) Re-Creating the White Terror on the Screen Sylvia Li-chun Lin; 4) Reclaiming Taiwan’s Colonial Modernity: The Case of Viva Tonal: The Dance Age Tze-lan D. Sang; 5) Cultivating Taiwanese: Yen Lan-chuan and Juang Yi-tseng’s Let it Be (Wu Mi Le) Bert M. Scruggs; 6) The Politics and Aesthetics of Seeing in Jump! Boys Hsiu-Chuang Deppman; 7) "Should I Put Down the Camera?": Ethics in Contemporary Taiwanese Documentary Films Kuei-fen Chiu; 8) Documenting Environmental Protest: Taiwan’s Gongliao Fourth Nuclear Power Plant And the Cultural Politics of Dialogic Artifice Christopher Lupke; 9) Sentimentalism and the Phenomenon of Collective "Inward-looking": A Critical Analysis of Mainstream Taiwanese Documentary Li-hsin Kuo

Critically-Acclaimed Taiwanese Documentaries

The 2010 Golden Horse Award for Best Documentary went to “Hip-Hop Storm”, directed by Su Che-hsien---a young, first-time Taiwanese filmmaker still earning his masters degree. “Up the Yangtze” by Yung Chang, a Chinese-Canadian director won in 2009. “KJ” by Cheung King-wai, a Hong Kong director won in 2008.

Taiwan’s filmmaker Shen Ko-shang beat other rivals to receive the award for his Double Happiness Limited: The Crazy Chinese Wedding Industry, a film about the values of love and marriage shared by Taiwanese and Chinese, and the wedding photography industry that generates profits of at least NOT$10.5 billion per year in Taiwan. Chinese directors Yeh Yun and Wang Yang finished second and third respectively.

Mickey Chen, Queer Taiwanese Documentary Maker

Filmmaker and author Mickey Chen, 44 in 2011, is best known for making documentaries that focus on Taiwan’s gay community. His first, Not Simply a Wedding Banquet (1997), was codirected with Mia Chen . The film follows Hsu Yu-sheng and his American partner Gary Harriman, who in 1996 became the first gay couple to hold a public, though not legally recognized, wedding in Taiwan. Chen’s Boys for Beauty (1999) and Scars on Memory ( 2005) explore the lives of gay teens and older homosexuals in Taiwan, while the 2003 documentary Memorandum on Happiness explores the issue of domestic violence among homosexual couples.] [Source:Ho Yi, Taipei Times (5/12, 2011]

Chen an outspoken homosexual activist who often refers to himself using the feminine nickname Lao Niang. He received a lot of attention after his book “Taipei Father, New York Mother” hit the bookshelves in January and quickly climbed up the bestseller chart. In the book, Chen’s story begins with his wealthy family falling on hard times during the 1970s energy crisis. Chen’s mother, whose own parents were born in China, and father move to the US to make money to feed their family in Taiwan, leaving Chen to be raised by his grandparents. After his parents split up, Chen’s father returns to Taiwan. Chen’s elder sister runs away from home and dies of a drug overdose aged 19, and his father, the embodiment of patriarchal oppression, is blamed for the Chen family’s many woes.

On his childhood Chen told the Taipei Times: “Children from dysfunctional families have different ways of licking their wounds. My brother is addicted to gambling, my older sister died of an overdose, and my younger sister spends her life in the frantic pursuit of love. I choose to hide in the abstract world of literature and the arts. I became parentless at the age of 10. Cinema taught me how to become the person I wanted to be.”

After graduating from the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Taiwan University Chen went to the City University of New York to study documentary filmmaking. On his time in New York, Chen said, “I struggled between the roles of activist and filmmaker and realized that it was impossible for me to play both. After Boys for Beauty in 1999, I dedicated most of my time to the [gay rights] movement, and it exhausted me. Activists give themselves over to the movement, leaving individual activists nameless. The artist inside me is too strong to remain silent. Memorandum on Happiness from 2003 was a key point in my filmmaking career. That film is my Dogme 95 Manifesto. It is very simple and devoid of stylish trappings. To me, the film is a return to the basics: storytelling.

White Terror Film

Prince of Tears, the latest film by the Hong Kong-based director Yonfan (who goes by one name) is a major new film dealing with the White Terror Era in Taiwan, when the ruling Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party, staged anti-Communist witch hunts that killed thousands. The film debuted at the 2009 Venice Film Festival and chosen as Hong Kong’s submission for the Academy Awards for best foreign language film. [Source: Joyce Hor-Chung Lau, October 13, 2009]

Joyce Hor-Chung Lau wrote in the New York Times: “The gorgeously crafted film, set in the 1950s, refers only obliquely to larger politics. Instead, it focuses on daily life in a remote Taiwanese village where anyone---a schoolteacher, a housewife, a soldier---could commit a political faux pas and be sent to the execution squad.”

“The project originated with the real-life story of the actress Chiao Chiao, a longtime friend and collaborator of Yonfan, whom she met in Hong Kong when she was a starlet there from the “60s to the “80s. The actress, who uses only her surname, grew up in Taiwan, but hid her childhood memories of the White Terror for years until she found a confidant in Yonfan, who also grew up in Taiwan in the 1950s. Several years ago, they decided to make a film based on her memories.”

“The film opens with a scene of a perfect-looking family in Taiwan: a handsome air force pilot, his pretty, doting wife and their two girls. But, after Kafkaesque political complications, the parents are dragged off and the father is killed in a field. As the executioners fire their shots, his daughters hide in the tall grass in a desperate attempt to get one last glimpse of him. The younger sister---the character representing Chiao Chiao---is sent to live with an eerie and physically scarred government agent nicknamed Uncle Ding, whom she suspects is the informer who turned in her father. In a strange turn of events, her mother is released from a prison camp and---under pressure to resume a normal family life and support her girls---gives into advances by Uncle Ding, whom she marries.”

“My father really did play the accordion, Chiao Chiao said in an interview, referring to the idyllic opening scene in which he serenades his daughters. I remember my mother going away and coming back. I remember being separated from my sister and being sent to live with Uncle Ding in a warehouse. My mother really did remarry. She’s still in Taiwan today and 88 years old.”

Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s “City of Sadness” (1989) is the last major film to portray Taiwan’s White Terror.

Image Sources: YouTube, IMDB

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2012