CHINESE FILM

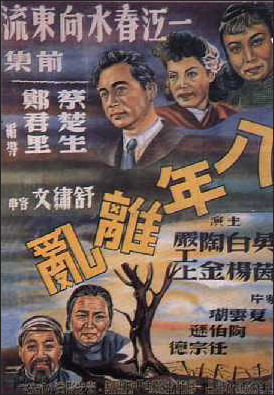

The Spring River Flows East_

China has one of the last remaining Communist film industries. State studios still produce and widely distribute numerous patriotic, propaganda films, known among Chinese film makers as “main melody.” China produces three main kinds of movies: commercial films, propaganda films and art films. They sometimes go through a similar screening process but are produced with different goals in mind and different relations with the government. Chinese art films are popular with the Western art house crowd but are often hard to find in China even on pirated DVDs. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Chinese filmmakers needed to sell a movie to Europe and the U.S. to make a profit. This is no longer the case, with China's robust box office.

Chinese film gained international acclaim in the 1980s and 1990s. Films by director Zhang Yimou — such as “Raise the Red Lantern” and “To Live” — addressed social issues such as the lives of women in the precommunist period and delved into the terrible things that happpened during the Cultural Revolution. His films, which have ones disapproved by the government, have been censored and banned, from the government. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, “Countries and Their Cultures”, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”: China is one of the world's leading producers of feature films, yet, except for a handful of works Chinese cinema little known in the rest of the world. Language has restricted Chinese movies' mobility, especially since most of them are not subtitled, but so have the country's longtime planned economy and socialist politics, and government censorship of works deemed critical and not suitable for foreign screening. The century of Chinese cinema is generally organized into six generations of filmmakers and their works, each period having certain characteristics. Although qualms occasionally surface concerning this categorization scheme — such as the overlapping of generations and the lack of clear-cut delineations — nevertheless, it has held fast. [Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

Based on global box office earnings China is now the largest film market in the world. China, beat out the U.S. for the first time ever in 2020, thanks in part to more aggressive Covid-19 lockdown measures that allowed movie theaters in reopen earlier. In 2020, China’s box office pulled in $3 billion compared to $2.2 billion in the U.S. China was home to the second largest film industry in the world after the United States in terms of money before the coronavirus struck in early 2020. It surpassed India in the 2010s to take the No.2 spot. In 2015, box office revenues in China were more than $6.5 billion, compared to $11 billion in North America, including cinema advertising revenue. In 2019, China pulled in $9.3 billion compared to $11.4 billion in the U.S. [Source: Adario Strange, Quartz, November 12, 2021

Around 800 movies are made in China every year. China is one of the largest film producers in the world, along with the United States and India. China’s film industry produced over 500 films in 2009, compared to just 100 in 2002. In 2010 more than 520 films were made — about as many as in America. Only India produced more. Only a small number of Chinese films make it to theaters, and many of these are produced by the state-run China Film Group and often play on a swelling national pride to attract wide audiences. Of the 330 films were made in China in 2006 less than half made it to theaters. Most went straight to DVD. Some were never seen, Blockbusters and romantic comedies dominated the box office. The Bureau of Film Administration is the government bureaucracy that presides over the Chinese film industry.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM INDUSTRY AND MOVIE BUSINESS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FILM STUDIOS AND MAKING CHINESE FILMS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE-MADE BLOCKBUSTERS AND POPULAR COMMERCIAL MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; FILM, CENSORSHIP, CRITICISM AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com ; WANG JIANLIN AND WANDA: THE BILLIONAIRE AND HIS THEATERS AND FILM PROJECTS factsanddetails.com ANIMATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF CHINESE ANIMATION AND CLASSIC ANIMATED FILMS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Chinese Movie Database dianying.com ; Internet Movie Database /www.imdb.com ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com ; Expert on Chinese film: Stanley Rosen, a professor at the University of Southern California.

Film studies: 1) Asian Film Connections (Asia Pacific Media Center, Annenberg Center for Communication, University of Southern California). Their website includes: 1) A list of all films made in China, India, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan from 1998 on, including basic information such as synopses, filmmakers, cast, length, format, and availability of prints. 2) Eight to fifteen highlighted films and directors from each country, with detailed information and video clips. 3) A list of all internationally awarded films of each country from 1988 on Reviews, essays, interviews and filmographies, plus reprints from Asia's leading film journals, such as Cinemaya and Movie/TV Marketing. 4) Press kits and contact information. (5) Links to other relevant websites. 2) Hong Kong Film Archive (Leisure and Cultural Service Department) has an official web site that includes Archive Functions, Public Access Facilities, Film Programmes and Seminars, Exhibitions, Archive Collections, Newsletters, Publications. 3) Hong Kong Movie Database (Ryan Law, Hong Kong, China)including film database, photos and reviews of Hong Kong films. 4) Chinese Film (China Film Archive, PR China) Database by (China Film Archive) is a Chinese-language site on films produced in the PRC, but also from Hong Kong and Taiwan. It contains film descriptions, pictures and biographical data from the film industry. 5) Lu Pin, (Hong Kong, China) is a Chinese-language site with A very extensive database covering Chinese films made in mainland China (from 1905 till present), Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other regions. This tool is searchable (title, actors, etc. etc.) in English and in Chinese, includes information on awards, and has a section on "News about Chinese Movies". Some film data in the database even give full text film critiques.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “Film and Television Culture in China”by Zhifeng Hu and Haina Jin Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese Films in Focus: 25 New Takes” by Chris Berry Amazon.com; “Chinese-Language Film: Historiography, Poetics, Politics” by Sheldon H. Lu and Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh Amazon.com; “Chinese Film: Realism and Convention from the Silent Era to the Digital Age” by Jason McGrath Amazon.com; “China on Screen: Cinema and Nation”by Christopher Berry Ph.D. and Mary Ann Farquhar Ph.D. Amazon.com; “China on Film: A Century of Exploration, Confrontation, and Controversy” by Paul G. Pickowicz Amazon.com; “Chinese Cinema: Identity, Power, and Globalization” by Jeff Kyong-McClain, Russell Meeuf , et al. Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Villages, Awards and Acclaimed Movies in China

In the Mao era propaganda films were brought to rural villages by the equivalent of barefoot projectionists. Films, projectors, speakers and other equipment were loaded on to pack animals, such as donkeys, camels or horses, or on motorbikes or the backs of people and taken to rural areas where the films were shown outdoor on white canvas screen tied between trees, posts on storehouses or barns. By the 1990s, most villagers had access to DVDs and videos. Most small town and large villages had video rental shops or video rooms with scheduled video shows. Even people in small, remote villages without electricity, people can watch videos in a friend's house on a VCR or DVD player powered by a generator or car battery.

In the Mao era propaganda films were brought to rural villages by the equivalent of barefoot projectionists. Films, projectors, speakers and other equipment were loaded on to pack animals, such as donkeys, camels or horses, or on motorbikes or the backs of people and taken to rural areas where the films were shown outdoor on white canvas screen tied between trees, posts on storehouses or barns. By the 1990s, most villagers had access to DVDs and videos. Most small town and large villages had video rental shops or video rooms with scheduled video shows. Even people in small, remote villages without electricity, people can watch videos in a friend's house on a VCR or DVD player powered by a generator or car battery.

Chinese-born Chloe Zhao won the Oscar for best director in 2021 for the film “Nomadland” (2020) but word of her achievement was muffled in China because she had badmouth the Chinese government in the past. Otherwise, the actress Gong Li told Variety that even an Academy Award nomination is a big deal for Chinese.“Chinese people take Oscar very seriously,” she said. .”Most Chinese people follow the Oscar ceremony, so if we get nominated, or even win, that would make Chinese people very excited.” [Source: Tim Gray, Variety, February 6, 2021]

The Golden Horse awards have been dubbed the Chinese Oscars. They were launched in Taiwan in 1962. The award ceremony is one of Asia’s most-prominent film events and focuses specifically on Chinese-language movies. While the majority of the nominated films come from Taiwan, Hong Kong and mainland China, any Chinese-language film is eligible to enter. The ceremony is usually held in Taipei. In the past most of awards went to talent from Taiwan and Hong Kong. These days mainland talent does better.

On the mainland, since 2005, the Gold Rooster Awards (by jury) and Hundred Flowers Awards (by the public) have been given on a rotating annual basis at The Golden Rooster and Hundred Flowers Film Festivals (See Below). In recent years, the former has been criticized for giving awards based on “friendship first, competition second,” as more than one person often wins in the categories of “best actress” and “best actor” (these winners are called a “double-yolked egg”). [Source: SupChina, July 5, 2018]

Chinese films do well at international festivals. In 1995, Chinese films won 48 prizes at international film festivals but hardly any of them were shown in China. The Minister of Propaganda Ding Guangen said, the main characters were "ignorant, barbarous and unhuman" and the films failed to exhort "lofty ideals and beliefs and excellent working style of the Communist Party."

Chinese History and Cinema

The Chinese film industry gotten to where its by navigating path through civil wars, World War II, transition from a capitalist to socialist system, the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and Deng Xiaoping reform era. In 2012, 60 per cent of the films and TV shows shot at Hengdian studio, the world’s largest film studio, were set during the Second World War and the Japanese occupation of China, typically with Japanese as bad guys. Ian Johnson wrote in the The New Yorker: “Chinese history makes an ideal topic for cinema and television; with the basic narrative firmly in place, emphasis can be placed on the colorful, the exotic, or the magical. Such stories also tend to please government censors. Hengdian productions are vetted by the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television, and scripts must avoid controversial or contemporary topics. Most screenwriters have internalized the official version of China’s past, so historical productions usually receive quick approval. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Several years ago, a new genre emerged on television, in which modern Chinese characters travelled back in time, gaining insights from historical figures. Censors, feeling that such stories questioned the superiority of contemporary life, banned the form in 2011. A government decree said that such shows “casually make up myths, have monstrous and weird plots, use absurd tactics, and even promote feudalism, superstition, fatalism, and reincarnation.”

“Still, the public cannot entirely be prevented from interpreting costume dramas with a contemporary eye. One of the most popular shows in China is “The Legend of Zhen Huan,” a Hengdian production, set in the eighteenth century, about a concubine who wins over the emperor through cold-blooded guile. Chinese bloggers dissect the stratagems that Zhen Huan deploys in her rise to the top; in one episode, she falsely accuses the empress of causing her to have a miscarriage. At the end of the seventy-six-part series, Zhen Huan is alone and friendless — the official moral of the story — but most viewers are impressed by her cunning. One blogger suggested that the palace drama offers useful lessons in “management theory and workplace strategy.”

Themes in Chinese Cinema: Socialist Values, Nationalism, Superhuman Powers

Paying homage to and encouraging traditional socialist values in a film’s content remain an important prerequisite to getting a film made in China. According to China Film Insider: “Even as new entrants change the face of moviemaking and marketing in China, the government continues to promote traditional values from the top down, with President Xi aiming to leave a lasting mark on arts and culture. A media industry self-discipline pledge and ongoing controls over content (especially from overseas) seek to limit perceived negative influences on audiences, while a resurgence in patriotic works is seen with productions such as the Hundred Regiments Offensive and a 3D film version of a popular revolutionary opera. [Source: Jonathan Landreth, Sky Canaves, Pang-chieh Ho, and Jonathan Papish, China Film Insider, December 31, 2015]

Ian Johnson wrote in the The New Yorker: Superhuman powers figure prominently in productions at Hengdian, the world's largest film studio, 400 kilometers from Shanghai. "Such stories defy the Communist Party’s official championing of science, but the censors let them pass, because they reflect a larger Chinese belief in the supernatural and allow filmmakers to demonstrate the superiority of China’s cultural tradition. One of my favorite productions in this genre is “The Anti-Japanese Magical Knight,” a 2010 story about a six-man team of martial artists who appear to defeat the Imperial Japanese Army single-handedly. In the goriest scene, one of the stars bursts into a Japanese fortress and punches a soldier with such force that his fist penetrates the man’s torso, causing him to split down the middle as if he were a block of wood; guts and blood spew like water from a hose. In other scenes, heroes fly or dodge bullets fired at point-blank range — they have the kind of Gumby-style elasticity that allows them to do extreme back bends. I watch it in the same campy spirit in which I watch “Airplane!,” but its tone is resolutely serious. Indeed, the six knights are meant to symbolize the way that the Chinese used ancient tradition to trump Japan’s modern military. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Crude nationalism has long been a feature of Chinese productions, but the government seems to feel that things have gone too far. According to Chinese press reports, an official decree has called for more realism — in Second World War films, one Chinese soldier is to be shown dying for every Japanese who dies. That could prove to be a bonanza for the extras: one estimate suggested that, last year, seven hundred million Japanese died in Chinese films. In February, the Communist Party organ, People’s Daily, said that anti-Japanese dramas were becoming “reckless inventions.”

Content and Features of Chinese Films

Crossroads (1937) Chinese films tend to feature more fighting and less sex than Western films. Miao Di, a professor of film and television at the Beijing Broadcasting Institute, told the Los Angeles Times, “The Chinese people have always been very sensitive about sexuality but not worried about violence.” Nurtured on king fu. Many Chinese find American films less violent than home grown ones. Some think films have had a significant social and cultural impact in China. Filmmaker Jia Zhangle told The New Yorker. “In the early eighties, many directors made films about women’s rights — about their confinement, their unhappy marriages — and, through these films, Chinese people realized women must be respected and treated equally.”

In an essay on the absurdity of China’s film culture and industry today called “Daytime Booze, Nighttime Party: Thoughts on the Present State of Chinese Cinema”, Zhang Xianmin, Professor of Beijing Film Academy, film producer and critic, and organizer of the China Independent Film Festival divided modern Chinese movie making into four parts: Chinese films, box office, international film festivals, and the role of the Internet. He argues that first, vibrant film culture exists only in a few major Chinese cities while zero film culture exists in all other places; second, mainland Chinese cinema is not competitive in the global market because it is yet to develop any unique and cross-cultural popular genres; third, award-winning Chinese films at various international film festivals do not have much influence on Chinese cinema but are heavily oriented towards China’s social and political realities; and lastly, Chinese audience consume more foreign films than the other way around. [Source: Zhang Xianmin, translated by Isabella Tianzi Cai, dGenerate films, September 29, 2010]

"I can outline three kinds of games that are played in contemporary China. First is the game of political leverage. For example, [Communist Party leader] Bo Xilai’s son Bo Guagua studies in London. Guagua came back to China once and delivered a speech in Peking University about his determination to contribute to China’s cultural industry. Many years ago Kim Il-Sung’s son said the same thing to his father. Second is the game of money. Han Sanping said that he wanted to invest 6 billion yuan in turning Huairou into China’s Hollywood. Jia Zhangke also said that he would donate 200 million yuan to support young Chinese filmmakers. Third is the game of fame. All of China’s film critics in their 60s agree that the love story in Under the Hawthorne Tree (dir. Zhang Yimou, 2010) is absolutely romantic and touching. And the officials at our film bureau insist that Aftershock (dir. Feng Xiaogang, 2010) is a realist film. This is why we have midnight drinking parties followed by late night dancing parties. So cinema stands alongside alcohol and parties. Under this condition, it is meaningless if a film wins an award in an international film festival. Time has changed. Now is different from ten years ago. An award-winner has little influence on Chinese cinema. Awards matter less than more practical things. The general public lives under stress. They consume bad popular culture and they are in turn the shapers of that bad popular culture. At least that’s their relationship with China’s mainstream media.

Struggling, Strong-Willed Women and Rural Settings of Chinese Communist Films

In a review of the book “Visual Culture in Contemporary China”, Wendy Larson wrote: by Xiaobing Tang examines four rural films and their representation of women, with the aim of showing how films set in the countryside continuously express socialist cultural aspirations and a commitment to the disadvantaged. [Source: Wendy Larson, University of Oregon, MCLC Resource Center, August, 2016. Book: “Visual Culture in Contemporary China: Paradigms and Shifts”by Xiaobing Tang. (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

The first film is “Li Shuangshuang” (Lu Ren, 1962), dating from the “idealist phase” of the genre. The film’s uplifting representation of the political activism of the main character — a woman who fights against a good-willed but reluctant husband for release from household drudgery — was enthusiastically received in the early 1960s. The second film is In the Wild Mountains (Yan Xueshu, 1985), which features a pair of peasant couples who swap their spouses, bringing to the excitable Guilan a husband who is more entrepreneurial and willing to take risks, and to her former husband Huihui a woman who is happy with a stable rural life. Yet neither couple is perfect, and the film veers away from the clear ideological vision expressed in Li Shuangshuang, moving toward ambiguity.

Women from the Lake of Scented Souls (Xie Fei, 1992), the third film, recounts the life of Xiang Ersao, who is married to an abusive man but has a secret relationship with a truck driver. When she suggests that they run away together, the driver demurs, and Xiang understands her dilemma and the hopelessness of her life. Although she initially tricks a young woman into marrying her disabled son, she eventually overcomes the cycle of violence and releases the woman, which suggests hope for a better future. The final film, Ermo (Zhou Xiaowen, 1994), again features a strong-willed woman who focuses her energy on selling enough noodles and blood to buy a large color television set. Although Ermo gets her TV — what Tang calls a “gigantic metaphor for Ermo’s blocked desire” — she is so exhausted that she falls asleep watching, never noticing that the screen has gone static. Intriguingly, each film features a truck driver — in two cases with suspicious moral values — highlighting the importance and danger of rural connections to the city. Overall, Tang emphasizes the way in which through “juxtaposition and recombination, we witness how these past creations acquire a new look and exhibit new meanings,” suggesting that despite the dated manner in which it appears to contemporary viewers, the clear socialist vision of Li Shuangshuangshould not be casually dismissed.

China’s History-Driven Versus Hollywood Character-Driven Films

Michael Keene wrote in Asian Creative Transformations:“In terms of story, much is made of this. The Chinese often say that they have a wealth of stories that can be told. But the question is: are these stories meaningful for international audiences? Chinese audiences are open to history and the retelling of history; this is evident in the classifications of genres from ancient to revolutionary history, to great revolutionary themes. In a sense the domestic audience have become habituated to history in TV serials, at least many of the older generation. Culture is never far away from the surface; moreover the Chinese language is full of historical references; at the same time there is a fondness for melodrama, which doesn’t translate into blockbusters very well. “In the television industry there is way of avoiding these issues and that is formatting. A Chinese version is made of an international program. However formats rarely apply to dramas and feature films. [Source: Michael Keene, Asian Creative Transformations, June, 2014]

“Most Hollywood stories are character driven: the most successful genres are not culturally specific, the exception being when the story involves foreign locations such as The Bourne Identity and 007 franchises. All audiences in the world can understand the formulaic action movie for instance; indeed Hollywood players put a great deal of emphasis on script.

And as Oliver Stone pointed out at the Beijing Film Festival in 2014 the Chinese film industry does a pretty poor job conveying its history. “It’s all platitudes,” he said. “We are not talking about making tourist pictures, photo postcards about girls in villages, this is not interesting to us. We need to see the history . . . for Christ’s sake. Mao Zedong has been lionized in dozens and dozens of Chinese films, but never criticized. It's about time. You got to make a movie about Mao, about the Cultural Revolution. You do that, you open up, you stir the waters and you allow true creativity to emerge in this country. [Source: Clifford Coonan, Hollywood Reporter, April 16, 2014]

Beijing Film Culture

On the dominant yet insular nature of Beijing film culture, Shelly Kraicer of the blog dGenerate films wrote: “Beijing has long been the capital of mainland Chinese independent film and avant-garde culture. No less than half of the dGenerate Films catalog are by Beijing-based filmmakers: Jia Zhangke, Liu Jiayin, and Cui Zi’en, to name a few. And yet, despite its openness to progressive artistic activity, Beijing has an intensely policed view of the cultural other and the potential role of these others in its cultural discourse." [Source: Shelly Kraicer, dGenerate Films, July 21, 2010]

"There may be several reasons for this dichotomy. Beijing has been a more homogeneous Chinese city until quite recently (dating to probably the early part of this century, with the internationalization of Beijing’s urban surface, at least, in the lead up to the 2008 Olympics). And Beijing remains (in a certain, conflicted, post-Cultural Revolution way), the incubator, curator, and protector of a certain idea of Chinese culture. This protective attitude leads Beijing’s cultural workers to patrol (though, again, for completely understandable reasons having to do with resistance to various colonialisms and post-colonial hegemonisms) the boundaries of us (Chinese) and them (foreigners). This attitude often strives to keep our (i.e. Chinese-made) cultural works in a safe zone, circumscribed and patrolled by rather regressive definitions of the Other. I’m generalizing, obviously, but I hope not uselessly."

"There are clear exceptions: many Chinese intellectuals I know joyfully and productively bring Western cultural theoretical concepts into their work, and play, creatively, in the spaces between Western post-theories and the various streams of Chinese historical cultural heritages. Western voices themselves, though, talking about Chinese art and artists, are entertained somewhat problematically.People in Beijing are often curious about what I’m working on (film research, for example), and are curious to hear my opinions, though they often far too quickly take these as somehow representative of a particular template of what a Westerner thinks about our Chinese movies (which is rather often far from the case, especially with my willfully idiosyncratic readings of what I’m watching here). But there comes a point in most conversations I have with Chinese colleagues where things sadly grind to a halt, to a refrain something like there are just certain things you won’t be able to understand, since you’re not Chinese. You can almost hear the intended effect: the portcullis clangs down, the drawbridge ratchets up, and the castle is secure with you safely outside. What can a non-Chinese person say to that? Any attempt to argue the point circles back to demonstrate that you just can’t know. It’s a completely self-sealing argument."

Beijing Film Academy

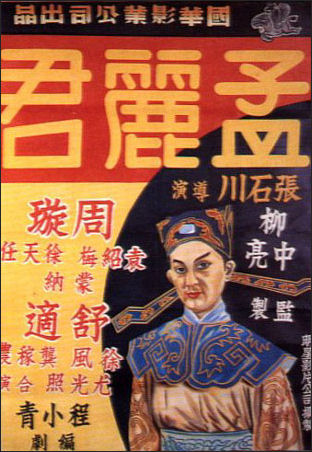

Meng Lijun (1940) Maya E. Rudolph, of dGenerate Films wrote, “ Since 1950, when Beijing Film Academy (BFA) and Beijing’s Central Academy of Drama (CAD) were founded, the institution of the film academy has created an inescapable framework of production resources and human networks vital to any aspiring Chinese filmmaker. An open portal to the mainstream film industry and the guanxi system that puts Hollywood’s old boy’s network to shame, China’s elite film academies and the pedagogy therein are widely regarded as a mandatory step for any student with ambitions on either side of the camera. [Source: Maya E. Rudolph, dGenerate Films]

“The connection between the film academies and China’s film industry, safeguarded by SARFT (State Authority on Radio, Film, and Television) and the guanxi network that links producers, professors, and promising students, is well evidenced by the roster of eminent filmmakers and their shared alma maters. Indeed, so ubiquitous is the Academy system in industry politics that the “generations system” implies not only a contemporary group of working artists with a common aesthetic model, but references the respective years these filmmakers graduated from BFA (i.e. “Fifth-generation” directors Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige, and Li Shaohong, to name a few, are all 1982 BFA grads.). From the mainstream to independent, from Zhang Yimou to Jia Zhangke to Liu Jiayin, rare within the galaxy of contemporary Chinese filmmakers is an artist without some relationship to China’s film and art academy giants. In most literal terms, the film academies control the means of production.

“At BFA — the crème-de-la-crème of China’s film academies — curriculum includes a comprehensive integration of film history and theory, practical and technical skills, and the guiding hand of state-controlled production and industry standards. BFA’s handbook specifies that graduating Directing majors “have the knowledge and capability in comprehension of literature, art theories and history; good taste in aesthetics and art appreciation; systematic knowledge of the basic rules of film and television directing; [and] video and audio expressive skills? Beyond presenting a daunting checklist, BFA’s distinct criteria suggest that theirs is a time-tested formula ensuring that a student with these technical skills and this artistic understanding can become a successful director.

“Admission to any Chinese film academy is largely dependent on the same benchmark as any national college or university: a series of rigorous interviews and the outcome of the supremely competitive gaokao, the nightmare standardized exam that looms as the culmination of every Chinese high school career. The gaokao, unlike the SAT, serves a primary determinant of a student’s college admissions, and, often, by extension, their eventual career within a certain industry. [Source: Maya E. Rudolph, dGenerate Films]

“Many students complain about the grade-grubbing, sub-par work of their peers. Most directing majors are required to produce a short work nearly every semester, projects that are shown in informal film festivals open to peers and friends. “A lot of the student films are really a joke,” said a CAD third-year Screenwriting major who wished to remain unnamed, “Everyone’s film is at least thirty minutes or more — [but] they are not high quality and no one really has strong technical skills, but the length proves to the professor that they worked hard.”

Problems with Chinese Film

Li Jingjing, a film critic for the Chinese-Communist-Party-run Global Times wrote: “I can understand why some people aren't the least bit interested in Chinese films, as many films over the years have continued to disappoint us with their lame plots and poor production quality. Even when some films became huge money earners, they usually only managed to do so by relying on huge star power instead of a quality story. As such I've always been a little embarrassed when it comes to introducing some of these big earning films to my foreign friends. [Source: Li Jingjing Source:Global Times, January 5, 2016]

According to China Film Insider: “In Xi Jinping’s October 2014 speech on the arts — released publicly a year later, in 2015 — the Chinese President railed against the numerous problems facing China’s creative industries: “plagiarism, imitation, stereotypes and repetition, assembly-line production, and fast-food consumption,” to name a few, and many in the industry openly acknowledge the shoddy feel of most films. High profile plagiarism and copyright infringement claims have surrounded some of this year’s big domestic movies, including Goodbye Mr. Loser, Chronicles of the Ghostly Tribe, and Mojin — The Lost Legend. [Source: Jonathan Landreth, Sky Canaves, Pang-chieh Ho, and Jonathan Papish, China Film Insider, December 31, 2015]

“High-level allegations of ticketing fraud moved regulators to issue new rules on ticket sales, launch an official online box office reporting platform, and reach an agreement with the Motion Picture Association of America thatwill allow Hollywood studios to audit Chinese box office receipts. The latest draft of the long-awaited Film Industry Promotion Law, released publicly in November, would codify the framework for box office regulation and add penalties for fraud.

According to the China Daily: China has the most 3D screens in the world. The usual practice in most countries is to screen both the 2D and 3D versions, but in China, only the 3D version is released. Disgruntled customers are left with no choice but to pay more to have a 3D experience. What's more, despite the 3D propaganda, very few are actually shot in 3D resulting in lower quality films. Raymond Zhou said, "I feel that 3D technology is a double-edged sword. To convert those films from 2D to 3D is actually a lazy and cheap way to make a quick buck." [Source: China Daily, June 20, 2013]

“In June 2013, the release of Jurassic Park 3D and Fast and Furious 6 were postponed while domestic blockbuster "Switch" did hit screens. The popular Dreamworks animation "Croods" was also suddenly called off due to "contractual reasons" while domestic animations "Kuiba" and "The Adventures of Sinbad" WERE released. It's an open secret that the month for domestic film protection is here. “Raymond Zhou said, "The government agency that is doing that is playing the role of God that can not actually give you the rationale or the reason why it’s feasible and necessary. So it's quite random. I think that a more healthy and sound system of protection should be ironed out and all domestic movies should in a way be benefited from that."

Oscars and China

Each year, China’s sole entry for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film is selected by the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, which regulates the Chinese film industry. On the selection process in 2013 and 2014, Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times’s Sinosphere blog: “Critics of the Chinese film system say the selections are capricious and hobbled by censorship restrictions. In 2013, the widely praised “A Touch of Sin,” directed by Jia Zhangke, was never allowed by the film bureau to be released in Chinese theaters, presumably because of its depictions of violence and economic disparities in contemporary China. That meant, of course, that China did not submit it as an Oscar entry, and a World War II drama, “Back to 1942,” directed by Feng Xiaogang, was chosen instead. [Source: Edward Wong, Sinosphere blog, New York Times, September 11, 2014]

In 2014, Zhang Yimou’s “Coming Home” was seen as good choice. Zhang has said his view on the issue has never changed”. He told the Guangzhou Daily. “The right to recommend Oscar entries is not in my hand. You have a script and feel it could be a winner, but a year later when you’ve finished the shooting, how can you ensure that Sapprft will recommend you?There is only one chance — that is you finish it well, then luck strikes and you are recommended,” he said. “Then luck strikes again, and five out of nine, you’re among the Oscar finalists. Then only when luck strikes again can you win. You need three lucky strikes in a row.”

In 2014, China’s film authority surprised everyone by submitting “The Nightingale,” a Sino-French co-production directed by French director Philippe Muyl, as its entry for the the 2015 Academy Awards. The Wall Street Journal reported: “The Nightingale,” which tells the story of a road trip taken by an old man and his spoiled granddaughter through the southern Chinese countryside, is an adaptation of Muyl’s uplifting 2002 odd-couple drama “The Butterfly,” which was well-received in China despite never being officially released here. In choosing “The Nightingale,” China’s film authorities passed over a number of strong candidates, including period drama “Coming Home” by Zhang Yimou, arguably the country’s most prominent director, and Diao Yinan’s noirish “Black Coal, Thin Ice,” which walked away with the Golden Bear award at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year. [Source: Lilian Lin and Josh Chin, China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, October 10, 2014]

In 2015, according to the Wall Street Journal, Chinese film authorities surprised everyone again by submitting “Go Away, Mr. Tumor” — a crowd-pleasing romantic comedy that was big at the box office but light on gravitas and rave reviews — as the country’s official entry in the Foreign Language Film Award at the Oscars. The move even surprised the director of “Mr. Tumor,” Han Yan, whose name wasn’t previously widely known in China, who said he felt “extremely lucky” that his film was chosen. “Go Away, Mr. Tumor” is a romance based on a popular online comic about a female cartoonist who fights cancer and falls in love with her doctor. It has grossed more than 510 million yuan so far since its release earlier this summer, and stars Bai Baihe of the 2011 surprise comedy hit “Love Is Not Blind” and the California-born heartthrob Daniel Wu. [Source: Lilian Lin, China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, October 10, 2015]

Film Festivals in China

The Beijing International Film Festival (BJIFF) was established in 2011 by the Beijing government Held for eight days every mid-April, BJIFF aspires to catch up to Shanghai International Film Festival (SIFF, See Below). Oliver Stone showed up at the festival is 2014 and, according to the Washington Post, proceeded lambast China’s movie industry for its censorship and silly offers of joint production with American directors and production teams. The Sundance Film Festival was held in Beijing in 1995.

“On a national level, the Golden Rooster and Hundred Flowers Film Festival is regarded as more traditional than international festivals. Founded in 1992, the festival tours different Chinese cities for four days every September. Since 2005, the Gold Rooster Awards (by jury) and Hundred Flowers Awards (by the public) have been given on a rotating annual basis. In recent years, the former has been criticized for giving awards based on “friendship first, competition second,” as more than one person often wins in the categories of “best actress” and “best actor” (these winners are called a “double-yolked egg”).

“FIRST is so far the only Chinese international film festival to specialize in promoting youth filmmakers. Growing out of Communication University of China in Beijing in 2006, it is held annually in Xining, a plateau city of northwestern Qinghai Province in July. In the southern tropical reaches of China, the Guangzhou International Documentary Film Festival sees the largest gathering of documentaries in mainland China. The 16th festival was held in December, 2018. The Hong Kong International Film and Television Market, or Filmart, is one of Asia’s biggest film industry trade show. It had 640 exhibitors in 2012 — 10 percent more than the previous year — hoping to sell their films to 5,200 buyers expected from around the world.

Shanghai International Film Festival

Founded in 1993, the Shanghai International Film Festival (SIFF) is the oldest and best known of China’s major film festivals. The 21st Shanghai International Film Festival, held in June 2018, showcased 500 films in 30 categories from 55 countries. “Out of Paradise”, directed by Batbayar Chogsom, won Best Feature Film, while Ala Changso from Tibetan director Sonthar Gyal won the Jury Grand Prix. (Gyal also won Best Screenplay, an award shared with Tashi Dawa.). This year’s festival ended with 468,000 tickets sold, a 9.4 percent increase from 2017. Nicolas Cage and Christoph Waltz appeared. Among the celebrities that showed up at he Shanghai Grand Theater to open the 24th Shanghai International Film Festival in 2021 were filmmaker Zhang Yimou, kung fu star Donnie Yen, veteran actor Zhang Hanyu, actress Ni Ni and heartthrob Wu Lei.

SIFF is operated by the Shanghai government and one its aims is to promote Chinese films overseas by facilitating their cooperation with foreign film companies But, according to SupChina, “despite its rising box office and popularity at home, the festival hasn’t gained much global attention. China’s other festivals, such as the Beijing International Film Festival , has faced the same problems. As the only Chinese film festival recognized by the International Federation of Film Producers Associations (FIAPF), SIFF has always carried with it lofty expectations, for both filmmakers looking for business opportunities and audience-goers seeking the season’s best movies, i.e., films from the “hot summer season” ( sh qī dàng). [Source: SupChina, July 5, 2018]

In 2014, SIFF accused of holding a fake press conference addressing the cancellation of the film “The Uncle Victory”, starring Huang Haibo, who was arrested for solicitation during a national crackdown on prostitution but was supported by the public, igniting a debate about the legalisation of prostitution in China. During a press conference a journalist at the back of the room shouted out demanding to know why the festival had pre-prepared all the audience questions and were ignoring the issue of The Uncle Victory. When festival jury member Gong Li appeared to address the issue she was cut off and her answer was not translated to English. The press conference had been delayed and switched to a smaller room. [Source: Stephen Cremin Film Biz Asia, June 15, 2014]

Pingyao Film Festival

In October 2017, renowned filmmaker Jia Zhangke launched a new festival on his home turf in northwestern Shanxi Province: the Pingyao Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon International Film Festival.” The festival, supervised by Italian film producer Marco Muller, opened with Feng Xiaogang’s Youth and presented 46 films, most which were making their China or Asia debuts. The third Pingyao International Film Festival was held in October 2019 with 54 films from 27 countries and regions. Highlights were Cannes Award-winning “Atlantique”, Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s “Balloon”, and renowned Hong Kong filmmaker Jacob Cheung’s new production “The Opera House”. Jia Zhangke and directors Zhang Yimou and Xie attended the festival.

The aim of the festival is to showcase independent films. Jia would like it to be China’s version of Sundance, America’s biggest independent film festival. But participants have been careful not to anger the Chinese government to prevent their films from banned and festival organizer have tried to avoid controversy to keep the festival from being canceled. Describing the first Pingyao Film Festival, Steven Lee Myers wrote in the New York Times: “The film chosen for the festival’s opening, “Youth,” became entangled in an unspoken rule of congress politics. Its nationwide release in October was abruptly canceled, even though a promotional tour had already begun. Many critics assumed the reason was that it depicted an event — China’s unsuccessful war in Vietnam in 1979 — that would have run against the congress’s message of national strength. [Source: Steven Lee Myers, New York Times, November 2, 2017]

“The delay was, naturally, the first question at the festival’s opening news conference, prompting an evasive answer from its producer, Ye Ning, the chief executive of Huayi Brothers Media. The festival’s artistic director, Marco Muller, then chided journalists to steer their questions to the film’s director, Feng Xiaogang, and two leading actresses. “Let’s emphasize the artistic aspects,” said Mr. Muller, an experienced organizer whose role in another inaugural festival, in the former Portuguese colony of Macau, ended with his abrupt resignation last year. Agang Yargyi, a Tibetan filmmaker who traveled from the western province of Sichuan to attend, expressed admiration for Mr. Feng’s choice of a historical subject, calling it “very daring.”

“Opening night drew more than 1,500 people, according to organizers. Fans pressed the barricades framing the red carpets to snap photographs of China’s biggest stars. These included the actress Fan Bingbing, whose latest film, a patriotic action blockbuster called “Sky Hunter,” also played here. It was made in cooperation with the People’s Liberation Army, in keeping with a government-encouraged trend to extol the country’s might. Its addition certainly bent the definition of independent. Such, it seems, are the compromises required to put on a festival. Its posters declare “Pingyao Year Zero,” signaling Mr. Jia’s hope that it will be long lived.Mr. Feng, the director of “Youth,” played down the questions swirling around the festival. Now 59, he saw the Cultural Revolution, and the headlong rush into capitalism that followed, and reminded younger filmmakers that things had once been worse.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University ; Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021