FILM STUDIOS IN CHINA

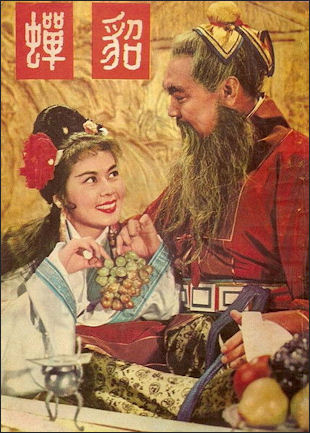

Diao Chan (1958) There are 16 major studios and 32 distribution companies in China. The world's largest film studio, Hengdian, is in China. It covers 35.5 million square feet. Zhang Yimou established Zhenbeibu Western Film Studio in Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia, in the 1990s. More than 100 popular films including Zhang Yimou’s “Red Sorghum” (1987) were shot there.

Three Chinese movie studios aimed to get stock exchange listings in the late 2000s. Huayi Brothers Media Corp. debuted on China's new small companies market in the southern city Shenzhen in late 2009, surging 148 percent on its first day of trading. The state-run China Film Group was planning to list in Shanghai. Beijing Polybona Film Distribution Co. was aiming to go public on the New York Stock Exchange in the second half of 2010. Polybona has already received funding from the venture capital firms Sequoia Capital and Matrix Partners China, with the second company investing 100 million Chinese yuan ($15 million). Polybona's businesses encompass movie distribution, production and multiplexes. Among its recent productions are the upcoming Jackie Chan historical epic “Big Soldier,” the historical thriller “Bodyguards and Assassins,” starring Donnie Yen, the police thriller “Overheard” and “Mulan..” Polybona had 50 movie screens by the end of 2009 and hoped to increase that number to 100 by the end of 2010 and 200 in three to five years. [Source: China Daily, November 3, 2009]

In 2016, China announced plans to build a $2 billion film studio as part of its effort to expand its cultural influence. Associated Press reported: The studio in the southwest municipality of Chongqing will include a theme park and tourist attractions, state media reported. Construction schedule to begin in early 2017 and is expected to cost $2.18 billion. Officials said they had operating agreements with several foreign partners and the park would include tie-ins with gaming and online entertainment and be named after President Xi Jinping’s signature “One Belt, One Road” program, a multibillion-dollar effort to deepen China’s economic and cultural ties with its western and southern neighbors reaching as far as east Africa. [Source: Associated Press November 28, 2016]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FILM INDUSTRY AND MOVIE BUSINESS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE-MADE BLOCKBUSTERS AND POPULAR COMMERCIAL MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; FILM, CENSORSHIP, CRITICISM AND THE CHINESE GOVERNMENT factsanddetails.com ; WANG JIANLIN AND WANDA: THE BILLIONAIRE AND HIS THEATERS AND FILM PROJECTS factsanddetails.com ANIMATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF CHINESE ANIMATION AND CLASSIC ANIMATED FILMS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“Shanghai Filmmaking” by Huang Xuelei; Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese Films in Focus: 25 New Takes” by Chris Berry Amazon.com; “China on Screen: Cinema and Nation”by Christopher Berry Ph.D. and Mary Ann Farquhar Ph.D. Amazon.com; “Chinese Film: Realism and Convention from the Silent Era to the Digital Age” by Jason McGrath Amazon.com; “Chinese Cinema: Identity, Power, and Globalization” by Jeff Kyong-McClain, Russell Meeuf , et al. Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Shanghai Film Studio

The Shanghai Film Studio is one of the oldest film studios in China. Run by conservative bureaucrats, it is known mainly for producing boring, risk-adverse movies. If these bureaucrats don’t like a script the film doesn’t get made. There are known for ditching entire project because they didn’t like one little detail. These days, the funding it receives is so low, it can hardly make any films period.

Shanghai has always considered itself the birthplace of Chinese cinema, starting with the silent movies of the 1920s that blossomed into the golden era of lavish productions of the 1930s. On the outskirts of Shanghai today there are huge studios, some working in tandem with Hollywood, make multimillion-dollar blockbusters. People here take pride that the city is a relatively open place for moviemaking, new genre animation and the best film festivals, setting it apart from staid and political Beijing to the north.

Like other businesses in China, China's film studio have their fingers in numerous enterprises. A director at the Shanghai Film Studio told the New York Times that it wasn't necessary for his films to make big profits because the studio earns a steady income from a metal factory it runs. Studios are now beginning to seek financial backing from the U.S. and abroad now that they are getting less money from the Chinese government.

The Huayi Brothers Media Corp, which Morgan Stanley called “China’s Warner Brothers for tomorrow, and China Film Group, are two of China’s largest studios. Huayi produced one romantic film that triggered a travel boom by Chinese tourist to the Japanese island of Hokkaido.

Rise and Fall of the Shanghai Film Industry

Chen Changye wrote in Sixth Tone: ““Although many filmmakers fled to Hong Kong after the Communist Revolution in 1949, Shanghai was nonetheless able to preserve its status as the irreplaceable core of China’s film industry, thanks to its well-established sector and moviegoing culture. Classic Chinese films from the 1980s, such as “Evening Rain,” “Legend of Tianyun Mountain,” and “The Herdsman” were all conceived in Shanghai. In recognition of the city’s contribution to global cinema, the Shanghai International Film Festival, which was held for the first time in 1993, is the first international film festival in China to have been given A-list status by the International Federation of Film Producers Associations. [Source: Chen Changye, Sixth Tone, June 22, 2017]

Asia Film Company Studio in Shanghai in the 1930s “However, around the beginning of the 1990s,” when Chinese began watching television more and going to movie theaters less, “ Shanghainese films lost the luster that they had acquired in previous years. Once the shining pearl of the Chinese film industry, Shanghai is no longer the main producer of the nation’s leading films and filmmakers; instead, it now finds itself on the periphery of a movement led by Beijing. Despite a wave of industry reforms beginning in 2002, Shanghai films have yet to return to their former glory.

“Compounding this decline is the fact that Shanghai’s film industry has also missed out on key opportunities for technological innovation. In October last year, the Shanghai Film Group’s technology plant shut down its film-processing line. The director of the plant, Chen Guanping, had stated that — at the company’s peak — there would be eight production lines and over a hundred employees working at the same time. In truth, the firm’s technical experts had predicted as early as 2005 that digital technology would eventually replace rolls of photographic film.

“At that time, however, experts expected the transition to be gradual. But then, the age of digital film took the world by storm. From 2012 onward, the group’s film-processing activities were in free fall. Four years later, the few production lines still in operation finally ground to a complete halt.

Rise of the Beijing Film Industry

Beijing ranks number No. 1 in terms of film production capacity in China. It had 350 Chinese-made films and 25 theater chains in 2017, according to official data. Chen Changye wrote in Sixth Tone: “These days, Beijing is considered the Hollywood of China. As China’s political and cultural center, Beijing is home to the nation’s most renowned celebrities and movie moguls. As regulation of film distribution became lighter and lighter, the dynamic among the three main players in China’s film industry also changed. Production levels at the Changchun Film Group slowly fell behind the pack; the Beijing Film Studio became a subsidiary of Central Motion Pictures; and the Shanghai Film Studio continued with the old model of state-run operation. It was precisely at this difficult juncture that many of the talented directors, cinematographers, and actors upon whom Shanghai’s film industry was so reliant chose to sever ties with the city and move north to Beijing. [Source: Chen Changye, Sixth Tone, June 22, 2017]

“The Beijing Film Studio’s growth despite the unstable economic conditions of the 1990s contrasted starkly with Shanghai’s downturn. Unfortunately for the latter, Beijing had two formidable advantages. The first of these was power. At the time, budding filmmakers had to navigate a maze of complex bureaucratic procedures, such as submitting films to an organization known today as the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television — China’s movie censors — for examination and approval. During the rise of privately owned film and television companies in the latter half of the ’90s, many of the companies that would go on to form the vanguard of Chinese cinema, such as Huayi Brothers, Polybona Films, and New Pictures, all set up their headquarters in the capital as a means of reducing the costs involved in the mandatory examination process.

“The second advantage was talent. The Beijing Film Academy was, and remains, at the forefront of film and arts education in China, and it continues to provide a steady supply of talented filmmakers for the nation’s producers, virtually all of whom are based in Beijing. Meanwhile, by the turn of the millennium, Shanghai’s film industry lacked fresh talent, while a number of its veterans also chose to retire. With no new actors and filmmakers to replace the previous generation, the city has been left devoid of opportunities to make great movies.

Film Making in China

Michael Keene wrote in Asian Creative Transformations: One of the major challenges in making a film in China is that the script must be approved by censors (National Radio and Television Administration, formerly the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television and the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television) and the has to be made following that script. [Source: Michael Keene, Asian Creative Transformations, June, 2014]

“The problem of script applies less to an assisted production, where the film is made in China but intended for release elsewhere. But if a film is intended to be shown in the Chinese market the script has to be passed by SAPPRFT. This applies to all films but in the case of co-productions it can mean the project going off the rails. If the partner is a leading Chinese entity the script will be first examined by the China Film Coproduction Corporation (CFCC).

“The processes inherent in creative development run up against the history of film making. Much of the best cinematic work has evolved and changed during pre-production, even into the production and post-production stages. While everything is changeable the most valuable assets are the idea (story) and the final cut. While having the script completed beforehand is a necessity in order to get a permit in China, it does not allow for creative elements to be modified during production. If the final product deviates from the original script the work will not be released.

IP was a film, fiction and culture industry buzzword in 2015. According to China Film Insider: “In China, the abbreviation IP stands for more than intellectual property: it refers to stories with an existing audience that will follow as they are retold across different media platforms. Online fiction has become a key source of IP and new film scripts, leading an executive from one new studio to suggest a diminished role for traditional screenwriters in the filmmaking process, a call that sparked an outcry in the ranks of beleaguered writers. [Source: Jonathan Landreth, Sky Canaves, Pang-chieh Ho, and Jonathan Papish, China Film Insider, December 31, 2015]

Problems Making Films in China

Some filmmakers complain of how difficult to is to work in China The actress Natasha Richardson told the Times of London, “The whole Chinese cultural barrier has made things really difficult. The simplest things seem to involve translations from three different people. Everything takes so much longer than usual.” The producer Ismail Merchant said. “People don’t like saying “yes” here. They think about things, and you can’t do that when there's a shooting schedule to keep.”

Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore and John Horn wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Every movie project involves a certain amount of negotiation, but finding middle ground proved no easy matter when writer-director Daniel Hsia tried to film "Shanghai Calling" in China. To secure permission to make his story about a Chinese American lawyer relocated to the country's largest city, Hsia exchanged numerous screenplay drafts with China's censors. The government's film production arm, China Film, which co-produced the movie, wanted to make sure that Shanghai was depicted as an efficient modern metropolis, that locals were shown as "kind and hospitable," that the visiting lawyer comes to appreciate the country by the film's conclusion and that a plot about piracy would be rewritten into more of a business misunderstanding, Hsia said. "Back home in the States you are talking to just one person: the consumer. Here, you are talking to two: one is the government, the other is the consumer," says the Beijing-based American Dan Mintz, chief executive of DMG Entertainment, the Chinese partner for "Iron Man 3". [Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore and John Horn, Los Angeles Times, September 22, 2012]

A number of films made in China are produced by China’s illegal, underground film industry. These films vary in quality from great to crappy. They are shown almost exclusively abroad. The films are regarded as contraband. Film maker risk heavy fines if their film project are discovered or they are smuggling film out of the country. Some directors have had their film making careers taken away by the government.

Hengdian World Studios, the World's Largest Film Studio

Hengdian World Studios (380 kilometers from Shanghai in Hengdian, Dongyang County) is the largest film studio in the world, and was called as "Chinese Hollywood" by Hollywood magazine of the United States. Covering almost 3,000 hectares (7,000 acres) and known to some as Chinawood, the facility has of 13 shooting bases with building areas of 495,995 square meters. The studio also has several records which include: the largest indoor Buddha figure in China, the largest indoor studio and the largest tourism spot. Since the filming of the movie Opium War in 1996, Hengdian World Studios has hosted more than 300 shooting groups and filmed more than 10,000 episodes of movies and TV-series as of 2005. Among other things, Hengdian World Studios, boasts a full-scale mock-up of the Forbidden City. There are two high-technical shooting studios, including the largest one in China with the area of 1,944 square meters. Among the supporting facilities are over 10 hotels, gym centers, nightclubs, Internet bars, tea houses and restaurants

Ian Johnson wrote in the The New Yorker: “Today, the Palace of the Qin King, an austere complex with curved roofs, red pillars, and a grand entrance of ninety-nine steps, rises amid the green mountains of southern China. Two thousand years ago, it was nestled in the scrubby hills of the north, where its occupant became the country’s first emperor. That structure now lies in ruins, but a replica of the original can be found at Hengdian World Studios, the largest movie lot ever built. On a drizzly morning in March, the palace’s front gate was besieged by a throng of tourists, while a watchtower was filled with actors filming a historical drama. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Nearby, extras assembled outside the gates of an imitation Forbidden City, hoping to join a cinematic mob. The set has been featured in dozens of productions filmed at Hengdian. Although it is a bit smaller than the original compound, in Beijing — some of the minor buildings have been edited out — it looks better, gleaming as it did at the peak of imperial rule. In the capital, the Forbidden City is run by one of China’s most obtuse agencies, the Ministry of Culture, and the buildings there look worn and battered. In March, all that was missing from the Hengdian model was Chairman Mao’s picture, on the Gate of Heavenly Peace — but that was only because the set had recently been used to shoot a movie that takes place before 1949.

See Separate Article PLACES IN ZHEJIANG PROVINCE: YIWU, WENZHOU, MOVIES, factsanddetails.com

Xu Wenrong, Founder of Hengdian Studio

Xu Wenrong (born 1935) is the founder and retired head of the conglomerate that owns Hengdian Studio: the Hengdian Group. Ian Johnson wrote in the The New Yorker: Xu started the company in 1975, when Mao was still alive and private enterprise was illegal. In many parts of China, Xu’s kind of market instincts resulted in the death penalty, but Hengdian was in Zhejiang Province, a freewheeling area of the country, and the company began churning out components for electronics, such as semiconductors and circuit boards. The Hengdian Group was worth $6.7 billion in 2012. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Venturing into films was an equally pragmatic decision. In the nineties, Xu took note of China’s booming domestic-tourism industry and devised ways to lure visitors to the area. He started with rural resorts featuring song-and-dance shows, but they fell flat. In 1995, however, he met another native of Zhejiang Province, the film director Xie Jin, who was preparing to shoot “The Opium War,” a movie about China’s humiliating loss to the British, in 1842. The film was a big propaganda effort, and Xie had top-level backing from the government, but he couldn’t find an outdoor lot for nineteenth-century street scenes. There was no time to waste: the film had to be released on July 1, 1997, when China would regain control of Hong Kong, which it had lost in the war.

“According to Xu’s autobiography, published in 2011, he promised Xie over dinner that he could build the set. Asked which films he liked, Xu had to admit that he never watched movies. Xie declined the offer and went home to Shanghai. That week, Xu sent an assistant to Shanghai to follow up. Desperate, Xie accepted, and in January, 1996, Xu started construction. Xu mobilized the small town, assigning tasks to a hundred and twenty teams. He made sure that everything was built by hand, as if a real town were being constructed. When Xie said that he wanted old, worn stones for the streets, Xu dispatched teams to the countryside to buy stone floors from the homes of peasants. He even took some tombstones from unmarked graves. Xu completed the set in August, and the film was released on time.

“Soon, other filmmakers came to Hengdian to use the “Opium War” lots, and they told Xu what other sets they needed. Xu began building full-scale, fairly accurate replicas of famous old temples and palaces. He also created a facsimile of the Communists’ remote wartime base in Yan’an, with caves dug into the mountains and a replica of the town’s famous pagoda.” In the early 2010s, “Xu’s son, Xu Yong’an, was running the company. He “told me that the replica will be given a different name: the Gardens of Ten Thousand Flowers. (This was the name of a labyrinth in the original garden.) Despite such minor alterations, Xu said, the goal was to faithfully re-create the past.

Shooting at Hengdian Studios

Johnson wrote in the The New Yorker: “A few movies filmed at Hengdian, such as Zhang Yimou’s 2002 martial-arts epic, “Hero,” have achieved international success, but most are tailored to the Chinese market. Hengdian specializes in costume pageants and patriotic war films.. The scripts call for romance, violence, and ambition, and the acting is melodramatic: to signal anger, performers arch their brows and widen their eyes like the door god of a Chinese temple. Makeup often recalls Peking opera: heavy and bright, as if the faces were meant to be seen onstage rather than in closeup. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“In March, productions being filmed included “The Wolfish Smoke of War,” “The City of Desperate Love,” and “The Priceless Key to the Palace.” I joined a crew surveying locations for “The Scout’s Sword” — a thirty-part television epic celebrating the courage of Communist commandos in China’s civil war.

The lot is twenty-seven times larger than Universal and Paramount studios combined, but it’s still not enough: on average, there are twenty movies or television dramas being filmed at Hengdian simultaneously, and many more directors are waiting to begin shooting. Filmmakers are eager to tap into China’s box office, which last year totalled $2.7 billion, surpassing Japan to become the world’s second largest. Others come to supply China’s gargantuan television industry: the country has more than twenty-five hundred stations.”

The actor Gu Dechao “was currently working as a casting director for a new television series, and he invited me to observe the shoot. The rain had driven the production into a makeshift studio across town. Hengdian is an improvised patchwork of new roads that have no signs, and we soon got lost. We drove past Ah Jiao’s offices, down the row of carpenter’s shops that make props, and along a road that dead-ended at a brick wall. There was a car-size hole in the wall and, after making a phone call, Gu drove through it. We lurched over a dirt field that looked like a vegetable garden strewn with rocks. Then we hit a road lined with derelict buildings and, after a few more phone calls and wrong turns, ended up in an alley of old factory sheds.

“Sitting out front, on a wooden throne, was Danny Lam, a Hong Kong set manager. He wearily waved us inside. At the entrance, there was no red light demanding silence; like most television shows in Hengdian, it would be dubbed later, so only minimal effort was made to keep things quiet during shooting. The factory had been transformed into the interior of a Chinese palace: red and black walls, with touches of gold leaf. The décor reminded me of Shanghai Tang, the luxury clothing store.

“Lam has worked in Hengdian for eight years. “It’s run by a businessman, so it’s efficient,” he said. “Whatever you need is here. Song dynasty, Ming, Qing — whatever. It’s all quickly available.” The series, “Four Young Famous Vigilantes,” is set in the nineteenth century. It’s about a comic band of heroes — a fencer, a boxer, a genius, and an alcoholic loafer — who are charged with safeguarding the imperial capital. The heroes have colorful names: the boxer is Iron Fist, the fencer is Cold Blood. The byzantine plot features a lot of skulduggery and double-crosses. The episode being shot involved Iron Fist trying to rescue his girlfriend, who had been kidnapped by the series’ main villain. When the weather cleared, the team planned to film a kung-fu sequence at the Forbidden City lot. The series was packed with action, but it also “emphasized a lot of history,” Gu said. “I don’t really know why, but that seems popular.”

Hengdian Studio Advantages

Johnson wrote: “Hengdian’s strongest lure is its price: Xu builds, renovates, and offers his lots free of charge. Chinese stars rarely earn the big money of their overseas counterparts, so production costs are a key factor in movie and television budgets. Shooting at Hengdian is such a relative bargain that it outweighs the site’s main drawback: remoteness. There are no air or rail connections to Hengdian, which has around a hundred and fifty thousand residents, and the closest large city is two and a half hours away by car. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Profits come from the studio’s subsidiaries, which provide costumes, props, design, catering, and other services. Revenues at the studio are also driven by tourism. Visitors pay fifty-five dollars for a two-day pass, and the Hengdian Group controls most of the area’s twelve thousand hotel beds.

“The baroque sets and costumed hordes recall Cecil B. De Mille’s glory days in Hollywood, from the nineteen-tens to the fifties. But those spectacles were some of the most expensive and profitable films of their era, helping to disseminate American culture worldwide. Hengdian films have low budgets, and the town has no villas, fancy night clubs, or high-end restaurants. There’s no equivalent of Rodeo Drive, and no cinema that’s elegant enough for a blockbuster première.

“As the Chinese-American producer David Lee told me, the town’s sleepiness can be an advantage. Some of Lee’s movies have been partly shot in Hengdian, including “The Forbidden Kingdom,” a 2008 action film starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li. Though top-flight talent can find Hengdian maddeningly dull, Lee said, “From a producer’s or director’s point of view it’s great: we’ve got you guys in one place, and we’ll shoot and shoot.”

Working at Hengdian Studios

Johnson wrote: Ah Jiao is “a thirty-eight-year-old studio manager who helps hold the anarchic lot together, setting schedules and settling disputes among the crews jockeying for shooting time on some stretch of Hengdian’s eight thousand acres. When I visited the lot, the studio was gearing up for dozens of spring productions. Ah Jiao was working twelve hours a day, six days a week, coördinating the crews. She was immaculately turned out — fluorescent-blue down jacket, red boots, black tights, shoulder-length permed hair — but her thin fingers repeatedly drummed her phone, and exhaustion rimmed her eyes. Ah Jiao’s phone rang, and she tried to pacify two factions vying to occupy a tenth-century palace. “Can you delay your shooting a day?” she asked one producer. “It would be better if you could wait and start later.” Calling another number, she said, “You can’t keep it that long. Can’t you speed it up?” [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“She put down her phone, turned to the men in the van, and relaxed: they were old friends who had worked with Ah Jiao many times. Led by Jia Zuoliang, an art professor and set designer, the crew was looking for a field where they could stage a battle from the nineteen-forties. That was an easy task: Ah Jiao’s specialty is staging wars. Hengdian keeps large expanses of farmland fallow, ready to host any army. Short on soldiers? The lot has nearly twelve thousand registered actors and extras, and Buddhist priests are available to bless the cast and crew. A studio slogan is: “Arrive with your script, leave with your reels.”

“The shoot for “The Scout’s Sword” was scheduled to start in two weeks, but pulling things off at the last minute is the Hengdian way. We parked on the crest of a hill, and walked past a bus filled with Red Army soldiers. A casting director for a television docudrama, “Mao Zedong,” stood on a row of sandbags, supervising two men who were dabbing black paint on clumps of red earth. “It’s raining,” the casting director said, pointing to the troops in the bus. “The soldiers can’t come out.”

“We pressed on, descending the other side of the slope, beneath glistening pine trees. In the distance was a small lake, and across it were the white smudges of a village. A wooden farmhouse appeared in the mist. These days, most of China’s villages are made of concrete, which means that a studio farmhouse need only be wooden to look generically old. The farmhouse had been built for an adventure film set in the Han dynasty (206 B.C.- A.D. 220), but Jia said, “We can use it. Things didn’t change too much in the countryside.” He snapped photographs and drew sketches for ten minutes, until the rain picked up. As we hurried back to the van, Ah Jiao said, “When do you want to shoot? The eighteenth, right? So what if I give it to you on the fourteenth?” ““Only four days to prepare?” Jia said. “Can’t we have it earlier?” ““It’s cheaper if you work faster.” “He laughed, knowing that he couldn’t win. “O.K.”

Actors at Hengdian

Johnson wrote: “For all its constraints, Hengdian can feel more like a movie town than Hollywood does. The big lot has long been passé in Hollywood; instead, films tend to be made on location or in front of green screens, with backgrounds later generated by computers. As a result, Hollywood itself has a hollowed-out feeling. At Hengdian, you immediately sense that movies are being shot all around you. Air horns blare to silence chattering extras, trucks off-load freshly made props, and directors yell at their assistants. Low-slung Porsches dodge potholes, and crews mill around on break. Once, I saw an actor, dressed as a Red Army soldier, rhythmically moving his head. Snaking out of his ammunition belt was a white wire, working up his torso to his head: earbuds. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“One day, Ah Jiao picked me up and took me to the Street of Great Knowledge, a boulevard lined with two-story buildings and groups of young people chatting and playing pool. “Hengdian drifters,” she said. “They come here looking for acting work. Some make it, but a lot just stay for a year or two and go home.” I wanted to meet some of them, so she drove down the road and dropped me off at a friend’s place — a photography studio run by one of the stalwarts of the acting community, Zhang Xiaoming. A trim forty-four-year-old with a receding hairline, Zhang was helping an actor with his résumé, which included images of the man as a Taoist priest, an emperor’s minister, and a nineteen-thirties businessman.

“An actress named Jennifer Tu stopped by. “I play spies, police officers, and court ladies,” she said, handing Zhang a memory stick containing photographs of her in costume. A round-faced twenty-six-year-old, she used to earn fifteen hundred dollars a month as an English translator in Shenzhen, and now makes a third of that. But she has seen herself on television. “It was about the Anti-Japanese War,” she said. “I was a journalist. I thought it was O.K. We know the history.”

“The door opened and Tian Xiping entered, greeting Zhang in a booming voice. Tian, who is forty-nine, used to sing for a living, but he told me that he had gained too much weight. “It looks bad if you’re a fat singer,” he said. “So I went into acting.” He now made a hundred and twenty dollars a day as a professional fat man, and worked about a hundred and fifty days a year. “The way I look, I can be a fat cook or a commander-in-chief,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of generals.” In his next role, he would be a pig butcher. “But there’s a cost,” Zhang said. Actors feel that they must live in Hengdian in order to find work, but this separates them from their families. Last year, Tian’s father was seriously ill, and Tian couldn’t get home before he died. “We’re like migrant laborers,” Tian said, nodding.

“While we were talking, a dark-eyed man walked in. He had a shaved head and a thin mustache, and he stared at me in an unsettling manner. I cocked an eyebrow at Zhang. “This is Gu Dechao,” Zhang said. Gu had recently performed as Chiang Kai-shek in a thirty-episode television series, and still looked the part. “Remember? Stalin, Churchill, Roosevelt, Chiang — the Big Four. If not for him, it wouldn’t be the world we know today! The baldy.” “The way I look, I always play villains,” Gu said. “He can’t play good guys!” “Bosses in triads, local ruffians, hoodlums, despotic landlords.” “But now he’s eaten too much and is fat. He used to be thin.” “A guy like me should look like an opium addict. You see me and you want to vomit.”

Construction and Computerization at Hengdian Studio

Johnson wrote: “The most stunning sight in Hengdian is a vast construction zone, roughly the size of Central Park, where trucks and cranes and hundreds of laborers are building a full-scale replica of the Gardens of Perfect Brightness. Originally built in Beijing’s suburbs, the giant complex featured stone mansions and exquisitely manicured grounds. In 1860, during the Second Opium War, British and French troops burned and looted it. [Source: Ian Johnson, The New Yorker, April 22, 2013]

“Re-creating the complex has long been Xu’s dream. Ten years ago, using nineteenth-century drawings as a guide he built a replica of one of the palace’s halls to prove that Hengdian could carry out the project. In 2008, the company announced the palace’s reconstruction. But Xu was blocked by the central government — company officials say they were told that the project was too sensitive and would use up valuable agricultural land. In Beijing, the palace ruins now serve as a “patriotic education base,” reminding visiting schoolchildren that China once suffered great humiliation at the hands of foreigners.

“Last year, work was allowed to commence at the site, and when I drove by construction was proceeding furiously. It wasn’t historically accurate — concrete, rather than wood, was being used for the pillars — but the façades looked convincing enough. The enterprise had already swallowed up villages, fields, temples, and graveyards, but it remained a delicate matter, and hadn’t been mentioned in the Chinese media. The site contains no signs offering an explanation. It was as if the heart of fire-bombed Dresden were being secretly reconstructed in the Bavarian countryside.

“It’s not entirely clear how Xu overcame the government’s concerns. (The company says that local officials believe the project will promote tourism.) He declined an interview, with company officials explaining that he was too busy at the construction site. In his autobiography, he writes that his wife found the Gardens of Perfect Brightness project so crazily excessive that she threatened suicide. The two later reconciled, however, and he forged ahead. “As a peasant, I hope to rebuild the Hengdian Gardens of Perfect Brightness to raise Chinese people’s spirit and China’s prestige,” he writes.

“Over time, Hengdian’s sets could themselves become relics, as the company embraces computerized spectacle. Last year, ten million dollars’ worth of digital post-production equipment was installed on the Hengdian lot. A spin-off company, Hongdian Film Production, will assist filmmakers in adding computer-generated graphics and digital color correction. It is the first company in China to offer 3-D rendering services.

“The general manager of the spin-off, Shi Xiongguang, showed me around the company’s offices, which had the sleek sterility of modern Hollywood: banks of computers, high-tech screening rooms, dubbing studios. We talked about the possibility that the spin-off would make Hengdian’s vast outdoor lots redundant. Shi emphasized, though, that technology was less important than storytelling. “From a technical point of view, you can re-create everything,” he said. “But the main thing is creating stories that people want to watch.”

Qingdao Wanda Film Studio

Wanda Dalian opened Qingdao Wanda Film studio outside Qingdai in the eastern province of Shandong in April 2018. At that time Steve Dickinson of China Film Insider wrote: The commercial part of the project includes a large retail mall, three separate amusement parks (theme park, water park, movie theme park, all indoors for year round operation), at least 6 separate hotels, two large exhibition centers, a large marina and a massive number of condos. Nothing except the condos have formally opened for business. The movie studio project is being conducted under the heading of Wanda Studios Qingdao, which operates separately from the commercial portions of the Film Metropolis. Management expects to begin formally renting out studios soon after opening. They indicate that some of the larger studios have already been used for Chinese domestic film productions. They would not discuss pricing with me nor did the person I asked know anything about the 40 percent subsidy that had previously been discussed in the media for using these facilities. [Source: Steve Dickinson, China Film Insider, April 16, 2018]

The entire project is 2500 mu (400 acres, 162 hectares). This is huge! The location is on the same side of the main road as the main sales buildings, away from the ocean, running up to the mountains to the west. This is a different location from what had originally been proposed. Thirty separate studio buildings have been built with another ten under construction and construction due to finish in October. The individual studios range from 10,000 square meters to 15,000 square meters. Each studio has a full sound stage, attached dressing rooms, full support set up (electronics, lighting, ventilation, etc) and 18 meter high ceilings. The studios were designed by a London architect and they have been built to meet an international standard. Management indicates that normal Chinese studios cost around 2000 rmb per square meter to build but that these cost 10,000 rmb per square meter...The construction and facilities build-out appears to be excellent and the claim that the studios were built to an international standard seems justified. Management claims this is the largest studio facility in the world and this claim also seems reasonable to me. The studio complex has a main headquarters building that can house a staff of 1000 people. The cafeteria can feed 1000 persons at a shift. Current staff is 200. The cafeteria complex is not being used. Presumably all of this will get into gear when formal rentals start in May of 2018.

“My impressions are as follows: a) Nothing at all is going on at the complex yet, so there is no way to predict what will happen down the road. b) Nobody seems to know who owns the land or the facilities. Nobody seems to know what the financial objectives are. Everyone seems to know that Wanda has full management control. C) Management states that they want to attract foreign movie projects and the elegant English language website evidences this. There was, however, no evidence of this at the physical site, I did not see any attempt to deal with any language other than Chinese nor any evidence that there had been any provisions made for services to any company arriving from outside China. But because I do not need any help with Chinese it is possible these services are available and I simply was not exposed to them.

“d) The studio complex is located far from Qingdao in a beautiful coastal location in the middle of nowhere. That means there are no carpenters, no electronics technicians, no retail supply of equipment (no wood, no nails, no paint, no electric drills, no lights, no speakers, no recorders, no cameras) nearby. Management told me that the film producers will bring in all the equipment and workers needed. I have worked with construction and engineering projects in China in places where you cannot even buy a nail or a screw and so I know how frustrating this sort of thing can be. It is not clear management understands this nor made any concrete plans to deal with these issues. e) The studio buildings are impressive. It was strange to tour all these expensive studios and not see a single project actually in operation. Will anyone come? And if they come, how will logistics be handled? Management seem confident enough, perhaps relying on the “if you build it and they will come” philosophy prevalent in China.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021