MAO-ERA FILMS

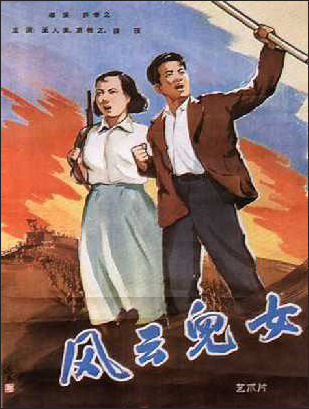

Flowers of the Motherland The film industry continued to develop after 1949, when the People's Republic of China was founded. In the 17 years that followed, up to the Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966, 603 feature films and 8,342 reels of documentaries and newsreels were produced. The first wide-screen film was produced in 1960. Animated films using a variety of folk arts, such as papercuts, shadow plays, puppetry, and traditional paintings, also were very popular for entertaining and educating children. The Chinese national anthem “The March of the Volunteers” comes from 1930s film “Children of the Storm”. [Source: Library of Congress]

Most early Communist film were poorly produced and edited stories smothered with sentimentality and propaganda. Later films were of better technical quality but still were propaganda pieces about happy workers and great Communist victories. Under Mao, China's most talented film directors directed propaganda films; famous actresses earned as little as $6 a month, barely enough to eat on; an many films featured long shots of wheat fields and industrial smoke stacks. Documentaries from the republican and Mao eras often featured a “Voice-of-God” commentary and were made for propaganda purposes.

Many early Maoist-era films tell stories about the war of resistance against the Japanese aggression and fighting against the Kuomintang during the Chinese civil war. The most famous of these were "Dong Cunrui" (1955) by Guo Wei, "The Red Detachment of Women" (1961) by Xie Jin and “Railroad Guerillas” (1956). The latter is a movie about a band of peasants that drive out Japanese imperialist occupiers. According to the Chinese government: These movies made everything seem fresh due to lively roles and plot. But at the same time they had a severe shortage and were limited by a lack of individual artistic character as well as different photographic style. Artistic rules were usually neglected. In this aspect, films made in the 1950s were inferior to those made earlier. Of the 603 feature films and 8,342 reels of documentaries made under the Communists from 1949 to the Cultural Revolution in 1966 few are shown anymore.

Christopher Harding wrote in The Telegraph: China’s own state-controlled cinema was shaped for decades by Mao’s insistence that culture serve political ends. The result was a genre of “main melody” films — suffused with Marxism-Leninism-Maoism and patriotism.Chris Berry said: In the Maoist era, documentaries always carried authoritative voiceover, interviews were rare, and the events filmed were often orchestrated. [Source: Chris Berry, professor at Kings College, London, dGenerate Films, November 14, 2013; Christopher Harding, The Telegraph, October 27, 2021]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; EARLY CHINESE FILM: HISTORY, SHANGHAI AND CLASSIC OLD MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS ACTRESSES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS — MADE ABOUT IT AND DURING IT factsanddetails.com ; RECENT HISTORY OF CHINESE FILM (1976 TO PRESENT) factsanddetails.com ; MARTIAL ARTS FILMS: WUXIA, RUN RUN SHAW AND KUNG FU MOVIES factsanddetails.com ; BRUCE LEE: HIS LIFE, LEGACY, KUNG FU STYLE AND FILMS factsanddetails.com ; TAIWANESE FILM AND FILMMAKERS factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. “The Goddess” (dir. Wu Yonggang)is available on the Internet Archive at archive.org/details/thegoddess . “Shanghai Old and New” is also available on the Internet Archive at archive.org ; The best place to get English-subtitled films from the Republican era is Cinema Epoch cinemaepoch.com. They sell the following Classic Chinese films: “Spring In A Small Town”, “The Big Road”, “Queen Of Sports”, “Street Angel”, “Twin Sisters”, “Crossroads”, “Daybreak Song At Midnight”, “The Spring River Flows East”, “Romance Of The Western Chamber”, “Princess Iron Fan”, “A Spray Of Plum Blossoms”, “Two Stars In The Milky Way”, “Empress Wu Zeitan”, “Dream Of The Red Chamber”, “An Orphan On The Streets”, “The Watch Myriad Of Lights”, “Along The Sungari River”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “General History of Chinese Film II by Ding Yaping Amazon.com; “The Chinese Filmography: The 2444 Feature Films Produced by Studios in the People's Republic of China from 1949 through 1995" by Donald J. Marion Amazon.com; “Working the System: Motion Picture, Filmmakers, and Subjectivities in Mao-Era China, 1949–1966" by Qiliang He Amazon.com; “Made in Censorship: The Tiananmen Movement in Chinese Literature and Film” by Thomas Chen Amazon.com Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Aims of Early Mao-Era Chinese Communist Films

In the 1950s, after Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, film was pressed (along with all other art forms) in the service of extolling the virtues of the Party led by Mao Zedong. Despite experienced hardships and setbacks after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, China's film industry made some reasonable good propaganda films. [Source: Lixiao, China.org,January 17, 2004]

Cinema was deployed by the Chinese Communist Party during the formative years of the People’s Republic of China to legitimize its rule and to propagate its political vision. Cinema and the Party’s social engineering intersected and interacted in areas such as popular film genres, movie star culture and rural film exhibition practices. The sports film genre, for example, created memorable iconographies and affective narratives to communicate the Party’s policies on the New Physical Culture (xin tiyu) in an effort to mould ordinary people into socialist laborers sound in both body and mind. [Source: “Moulding the Socialist Subject: Cinema and Chinese Modernity (1949-1966) by Xiaoning Lu (Brill, January 2020)]

Ying Qian, a PhD candidate in East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University said, The Mao era had infused in the population a love of cinema at a quite different register than that in the U.S. When I grew up in China’s 1980s, cinema wasn’t really seen as entertainment. Instead it was seen as a serious venue of artistic expression, and a way to think through large social problems. In recent years, the film industry in China has become more and more entertainment-oriented, but independent documentary continues the legacy of social cinema, staying connected to the society through a closer bond with historical reality."

Movies in Villages and Traveling Chinese Movie Men

In the Mao era propaganda films were brought to rural villages by the equivalent of barefoot projectionists. Films, projectors, speakers and other equipment were loaded on to pack animals, such as donkeys, camels or horses, or on motorbikes or the backs of people and taken to rural areas where the films were shown outdoor on white canvas screen tied between trees, posts on storehouses or barns.

Joseph Christian wrote in The World of Chinese,: “Zhao Jishan was the movie man. It was a job he didn’t even want. In 1974, Zhao was a hard-working, well-spoken, well-read worker with a penchant for drawing. He worked at the Communications Office of the Transportation Bureau writing news about the progress of road works. He knew nothing about mobile cinemas, but it was what the Bureau asked him to do. It was a temporary job, not at all a step forward to the promotion that he had been waiting for, a promotion to “permanent worker” status. But that year, the government had ordered films to be shown in all rural areas of China. Zhao was picked to lead a team that would travel to different villages playing movies for farmers on a mobile screen and projector. He refused. [Source: Joseph Christian, The World of Chinese, November 7, 2014]

“The next year, they approached him again to lead a mobile cinema unit. He resisted again, but it wasn’t really a choice any more. His skills demanded that he take the job. So, unwillingly, Zhao took command of Pangjia Town Movie Unit. “For three years, he and two men pulled a cart stacked high with reels, slides, a screen, a 30-kilogram projector, generator, record player, loudspeaker, microphone and poles. They brought news, entertainment and patriotic values to 49 villages in the local township. Their biggest enemies were rain and equipment failure. A drizzle required pitching umbrellas over the projector; a downpour meant a delayed screening. If the projector broke, they would stay in a village for as long as it took to get the equipment running.

“Villages in the township were, at most, an hour apart by foot. In the morning, the unit pulled its gear across the fields. Arriving before noon, they stayed as guests in farmers’ homes and would sweep their hosts’ yards in good faith. In the late afternoon, with lunch digesting warmly in their bellies, the movie men woke from their naps and began pulling the film reels out of their bags. As team leader, Zhao earned 35 RMB a month, about the starting salary of a university graduate. The salary was enough for Zhao, but he was also well received by the villagers. For lunch, they had steamed buns made from the village’s best flour. As the movie men ate, children would gather to watch.

One-hundred-thousand mobile cinema units pulled heavy carts all over China. Magic shadows dancing on screen put smiles on farmers’ faces at the end of a laborious day. Movies were a way for people to connect to the whole country-100,000 other villages were watching the same reels. During one showing, Zhao went into a field to relieve himself. As he approached a tree, he saw a young couple sitting holding hands. “Hey, aren’t you from another village?” Zhao asked the young man. “Yes, comrade. I came to watch the movie…You can see my pass. I have permission,” the young man stuttered. “I see, I see…Well, you might want to go back and watch the movie,” Zhao said with a wink. The couple hurried off. At 24 years old, Zhao was still not married. He chuckled at the boys who came from other villages to chase their lovers on film nights. Working on the road and holding a temporary job, he had little room for romance. He entertained himself by getting drunk with village leaders.

“One night, a chubby official challenged Zhao to a drinking contest. He boasted that he could drink Zhao under the table. “This time, I’m going to beat you like the PLA beat those imperialist thugs.” “As they walked to the official’s house, a gaggle of children trailed behind them. The little ones tried to sing the revolutionary song from the film they had just watched.

“The next morning, Zhao cursed his throbbing headache, pulled leather straps over his shoulders and began pulling the cart to the day’s destination. A few hundred meters out of the village, the cart sank into a crater of mud. The team, still half-drunk, pushed and pulled, but it wouldn’t budge. “Hey, hey, movie man!” The scrawny kids from the night before came running over. There were at least ten of them. They gripped the wheels with little hands. The soles of their bare feet slipped in the gooey wet earth as they helped heave the cart out of the mud. Ten grubby faces cheered, and Zhao cheered as well. He turned back to wave at them as his mobile cinema unit went on its way.

Chinese Village Movie Show

Joseph Christian wrote in The World of Chinese: “It was a hot 1977 summer day in Shandong Province when Zhao received news that he could move up to a permanent position in the county. A large crowd formed in the small clearing where he was preparing a screening. Farmers and village officials; the old and the young; lovers and friends. All waited with anticipation for Zhao and his crew to finish their preparations. “Hurry up, uncle!” a young boy yelled from the back. “All in good time,” Zhao made a funny face at the boy and finished putting up the 2.5 meter by 2 meter screen. Nearly one thousand people had gathered, jostling for space. A group of agile men climbed onto a brick wall. Some families even took up position behind the screen. No one wanted to miss the movie. [Source: Joseph Christian, The World of Chinese, November 7, 2014]

Sons and Daughters in Time of Storm (1935) “The most junior member of Zhao’s team arranged the reels in playing order. Zhao checked the projector to make sure that it was properly focused. With the flick of a switch, the machine hummed to life. Nothing appeared on the screen. “I thought I told you to get the slides!” Zhao said to the junior. Before starting a movie, the team was supposed to show news slides. The young man couldn’t find them. Zhao shut off the projector and apologized to the waiting audience. “Don’t ever do that again!” Zhao started to scold the young man, but was interrupted by the news announcements that his colleague started playing from a record player.

“At last, they found the slides and loaded them. They turned off the record player and put the projector on. Hand-drawn and hand-written bits of news flickered on screen. They explained to these villagers the feats of a skilled farmer from another village. Part of Zhao’s work was to collect stories of model farmers and share them with other villages. The unit used a special pen to draw and write the stories on the slides themselves.

“When the news slides were over, Zhao picked up the first movie reel, loaded the film carefully and waited for the crowd to calm down. “Good evening, comrades. Tonight we are showing one of the eight model operas, ‘Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy,’” he announced into a microphone. His voice bellowed from a speaker hanging from a pole that held up the screen.

“The eight model operas were sanctioned entertainment, based on traditional Peking Opera but infused with revolutionary spirit. They feature a lot of flag waving and soldiers shouting slogans; enemies of the revolution were usually crushed to the sounds of erhu and gongs. The crowd cheered. Zhao marched back to the projector and, teasing the audience, waited a moment before flicking the switch. As the screen brightened to life, the villagers broke into chatter. They knew the story. It had been played in that clearing many times before, but they still gossiped about the characters.

“Years after his promotion, Zhao, no longer the movie man, would take his young daughter on special outings to join in the fun of village screenings. By 1984, there were 120,000 mobile cinema units in China. They reached 97 percent of the population. Although their numbers have declined since the 1990s, films to this day are still shown in public spaces. One of Zhao’s team members never left the movement. He now plays films to villages once a month on a digital screen.

Third Generation of Chinese Film

John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”: Third Generation filmmakers shaped the aesthetics of Communist cinema, creating works that showed the tortuousness of the Chinese revolutionary wars leading up to 1949 and the sacrifices made by the people; life and reality in old China, denouncing its social darkness and praising laborers who rose up in resistance; and changes made after 1949, reflected in new persons and phenomena that appeared in the socialist revolution. This filmmaking period lasted until 1966, after which, during the decade of the dreaded Cultural Revolution, the industry almost came to a standstill, save for a few praiseworthy films such as Shan shan de hong xing (Sparkling Red Star, 1974), Chuang ye (Pioneers, 1974), and Haixia (1975). [Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

“Among the films about revolutionary forerunners, Cheng Yin's Gang tie zhan shi (Iron-Willed Fighter, 1950) and, with codirector Tang Xiaodan, Nan zheng bei zhan (From Victory to Victory, 1952), stood out; Su Li's Ping yuan you ji dui (Guerrillas on the Plain, 1955) and Guo Wei's Dong cunrui (1955) were also warmly received. The latter, along with Xiao bing zhang ga (Zhang Ga a Little Soldier, 1963) and Sparkling Red Star, led in the children-as-revolutionary category, and Xie Jin's Hong se niang zi juan (Red Detachment of Women, 1961) topped the list of women's films. The most successful films of the modern Chinese anti-invasion wars were Zheng Junli's Lin Zexu (1959), about the Opium War of 1838 to 1841, and Lin Nong's Jia wu feng yun (Battle of 1894, 1962).

“Films that denounced pre-1949 China often possessed a moving ideological and artistic spirit and were adapted from literary works of masters such as Lu Xun, Mao Dun, and Rou Shi. Perhaps the best were Shui Hua and Wang Bin's Bai mao nu (The White-haired Girl, 1950) and Sang Hu's Zhu fu (New Year Sacrifice, 1956), which was adapted from Lu Xun's novel of the same name. Others were Shui Hua's Lin jia pu zi (Lin family shop, 1959), from Mao Dun's novel; Shi Hui's Wo zhe yi bei zi (This Life of Mine, 1950), Xie Jin's Wutai jiemei (Stage Sisters, 1965), and Li Jun's Nong nu (Serfdom, 1963). The oppression suffered by intellectuals in old China was featured in works such as Xie Tieli's Zao chun er yue (On the Threshold of Spring, 1963), based on a Rou Shi novel.

“Many Third Generation directors focused on life in the new China, showing it as a time of new persons and new worlds united enthusiastically to serve the socialist revolution. Their films included Qiao (Bridge, 1949), directed by Wang Bin, and Chuang ye (Pioneers, 1974), by Yu Yanfu; both these works held the selflessness of the working class in high regard. Other films showed the new life in rural areas or depicted the role of Chinese People's Volunteers who fought in the Korean War in the early 1950s, such as Shang gan ling (Battle of Sangkumryung, 1956) and Ying xiong er nu (Heroic Sons and Daughters, 1964).

New Film Movement and Leftist Film-Making in the 1930s

1935 farmer film Leftist film-making began in the 1930s. The New Film Movement featured works on social issues that courageously exposed the grim and pressing problems in China at that time. Screenwriters and directors stepped out of the narrow confines of family ethics and tackled issues that affected Chinese society at large. "Three Modern Girls", written by Tian Han and directed by Pu Wancang, was the representative of the movement. The film depicts a young man and three modern girls choosing varied lives indicating the relations between the age and personal fates. When launched in 1933, the film won full of applauses. Later Xia Yan, Sun Yu, Cai Chusheng, Shen Xiling, Wu Yonggang and Yuan Muzhi created a batch of films combining their anxiety about the society, their concerns about the masses and their origination in arts, such as "Broad Road", "The Goddess", "Street Angel" and "Crossroads". [Source: chinaculture.org January 18, 2004]

In the 1930s the introduction of sound technology occurred in tandem with the politicization of the film world in the wake of the bombing of Shanghai in 1932. Major figures in the leftwing film movement that emerged at this time were the director Cai Chusheng and the writers Tian Han, Xia Yan, and Zheng Boqi. Resistance against imperialism and feudalism were central themes. Weihing Bao describes leftwing cinema as a radical movement that marshaled the tenets of modernist aesthetics toward the ends of mass politics. [Source: Reviewed by Jean Ma, Stanford University, Jean Ma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, February, 2016; Book: “Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915-1945" by Weihong Bao (University of Minnesota Press, 2015)]

During 1933 and 1935, the left-wing movement in filmmaking was introduced to Shanghai and flourished. Torrents (1933) (Kuangliu in Chinese), directed by Xia Yan and Cheng Bugao and produced by the Star Studio, was the first film of this genre. Many famed directors came to the fore and made outstanding contributions in art and literature, such as Yuan Muzhi's Street Angel (1937) and Shen Xiling's Crossroad (1937). They brought the darker, seamier side of society to light and gave expression to the wishes of the people to pursue their dreams as well as rebel against imperialism and feudalism. A great variety of artistic images were born and a number of acclaimed actors and actresses emerged. Butterfly Hu, Zhao Dan, Zhou Xuan and Shu Xiuwen were amongst them. [Source: Lixiao, China.org, January 17, 2004]

See Separate Article EARLY HISTORY OF CHINESE FILM factsanddetails.com

Mao-Era Chinese Films of from the 1950s and Early 60s

“The Life of Wu Xun” (Sun Yu, 1951): According to Radii: Mao Zedong personally denounced this film of Sun Yu’s after its release, claiming that the filmmaker’s ideological leanings proposed that revolution was not necessary. While the attack effectively cost Sun Yu his standing and his livelihood, it wasn’t until 35 years after the release of the movie that members of China’s Politburo admitted that Mao’s criticisms of the movie were baseless. Linda C. Zhang, PhD candidate, UC Berkeley, wrote: An early PRC film that fell on the wrong side of politics, and that was denounced for its ideological leanings. The Tale of Wu Xun is an epic film about the drive of one man to improve the educational opportunities of the underprivileged. It features a great dream sequence about the feudal oppressors keeping peasants illiterate and disempowered. [Source: Radii, February 2, 2021]

“Guerillas in the Plain” (Su Li & Wu Zhaodi, 1955): One of many People’s Liberation Army-worshipping movies that were released in the aftermath of World War II, Guerrillas on the Plain foreshadowed the patriotism that would come to saturate cinemas across China, with the movie set around a battle between the Chinese and Japan. Xueting Christine Ni, author and speaker, wrote: Works like Guerilla in the Plain (1955), Five Golden Flowers by Wang Jiayi (1959), and Liu San Jie by Su Li (1960) are still almost synonymous with this period even today. You can certainly see their influence in contemporary films from the mainland today.

“Family” (Chen Xihe & Ye Ming, 1957): An adaptation from Ba Jin’s epic novel of the same name, Family examines the struggles of young people living in China under a feudal system. Three brothers struggle with the idea that their wives have already been chosen for them. Peter Shiao, CEO and founder of Immortal Studios, wrote: 1950s zhuxuanlu [nationalistic cinema] when there was nothing else. An examination of the societal forces in Feudal China that was rotten to the core that necessitated a revolution.

“The Song of Youth” (Cui Wei, Chen Huai’ai, 1959): Charting the transformation of a young woman into a loyal Communist, this patriotic showing was cinematic proof at the time of the transformative power of Communism, as it won over the hearts and minds of young Chinese people. Linda C. Zhang wrote:: Based on the book by Yang Mo of the same name, Song of Youth was a blockbuster when it came out. It follows the trajectory of one young woman as she undergoes an ideological transformation to become a full revolutionary youth. The classic red sweater that she wears at the end of the film has become iconic.

“Five Golden Flowers” (Wang Jiayi, 1959): A romantic musical depicting the Communist Revolution, Five Golden Flowers takes the Bai ethnic community in Yunnan province as its backdrop, showing the diversity of cultures in China, while also depicting the supposed universality of the Communist struggle. Krish Raghav, artist and writer, wrote: A fascinating, full-color film set in a Bai commune in Dali, Yunnan. Produced back when the Communist Revolution was portraying itself as a universal struggle — this is all typical romantic comedy and Bai custom interwoven with emergent Communist ethos: meeting coal quotas, discussing exploitation, overthrowing landlords etc.

“Two Stage Sisters” (Xie Jin, 1965): This film depicts the different paths that a pair of opera singers take, with one seeking affluence and the other finding fulfillment in the socialist struggle. The film also charts changing historical conditions in China over the course of decades. Xueting Christine Ni wrote: Among the mass of anti-spy and revolutionary red films, Xie Jin’s women’s Trilogy (“Basketball Player No.5", “Red Detachment of Women”, and “Two Stage Sisters”) immediately spring to mind as the films to watch. Women’s emancipation, although by no means unproblematic, is considered one of the greatest achievements of the CCP. These films aren’t just about the changes in women’s roles in society, but also about how larger political and social changes had affected the lives ordinary people.

Flowers of the Motherland

Flowers of the Motherland and Its Impact

“Flowers of the Motherland” was one of the most influential movies in Chinese film history. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Released in 1955 as one of the first children’s movies made by the People’s Republic, it tells the story of a fifth-grade class with two rebellious children. Unlike the other thirty-eight children, they refuse to join the Communists’ Young Pioneers, even after hearing a stirring lecture from two demobilized soldiers. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 27, 2016]

“Eventually a flood of good deeds by the Communist children convinces the two recalcitrants to put on the red scarf, and everyone happily rows across Beihai’s lake to the words of the song “Let Us Paddle”:

After we’ve finished our day’s homework

We come to enjoy ourselves.

I ask you dear friends

Who gave us this happy life?

“The answer, of course, is the Communist Party and Chairman Mao, a message drilled into children of all generations. Even today, the song is part of the national music curriculum. Its effect was strongest in those earlier decades, when the Party had a monopoly of information and entertainment. Little wonder that the old people who gather in Beihai and other parks sing these songs of their youth. Their generation had no real folk songs or pop music, let alone outside sources of information; instead they heard only a mind-numbing glorification of the Party and the great leader.

Red Detachment of Women

The 1961 Chinese film “The Red Detachment of Women” by Xie Jin was produced under the personal direction of Zhou Enlai on a script by Liang Xin. Glorifying violent class struggle before the Communists came to power, it revolves around the heroic defeat and execution of an “evil landlord” by communist partisans in the 1930s. The film inspired a 1964 Chinese ballet that was one of just eight Party-approved model operas performed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and was performed for U.S. President Richard Nixon on his visit to China in February 1972.

“Red Detachment of Women” was a big success and major cultural phenomenon when it was released. It swept the Hundred Flowers Awards and was at the forefront of films that depict women as the backbone of the Communist party, affirming the Mao Zedong slogan that “Women hold up half the sky.” The screenwriter Phoebe Long wrote: Among the red films, [this one’s] “female empowerment” angle is quite novel, and the protagonist’s image is well-known in China and deeply rooted in the hearts of its people. One interesting point is that in the original, the film contained a romantic line for the protagonist, but due to the political atmosphere at the time it was eventually deleted. The content of the film and the experience of watching it reflect the characteristics of that era.

The novel by Liang Xin depicts the liberation of a peasant girl in Hainan Island and her rise in the Chinese Communist Party. The novel was based on the true stories of the all-female Special Company of the 2nd Independent Division of Chinese Red Army, first formed in May 1931. The group had over a hundred members. As the communist base in Hainan was destroyed by the nationalists, most of the members of the female detachment survived, partially because they were women and easier to hide among the local populace who were sympathetic to their cause.

Linda C. Zhang wrote: The main “character of Qionghua is basically a household name, as the movie was adapted into the famous ballet and film supported especially by Jiang Qing herself.” Jiang Qing was the wife of Mao Zedong and Gang of Four leader during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) “What’s not to love about a film that features a fiery heroine who escapes her own oppression and passionately seeks to right past wrongs? Patience, young padawan, says her mentor — the Party official who rescues her and guides her through her development.

See Separate Article Red Detachment of Women for the story of the film and revolutionary opera factsanddetails.com

Red Detachment of Women (1961)

Tragic End of Shi Hui During the Anti-Rightist Movement

Persecuted and misunderstood, Shi Hui was a talented actor and film maer who was caught up and ultimately destroyed by the Anti-Rightist Movement of the 1950s.Tristan Shaw wrote in SupChina: “During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Shi Hui was one of the most popular actors in China. Shi’s range was wide, and he portrayed a variety of mostly lower-class characters during his film career, playing a school principal, a tailor, a peasant soldier, a pimp, and even a (white) American capitalist. Whatever his role, Shi always brought depth and humanity to his characters, whether they were heroes or not. His performances in movies like Miserable at Middle Age and This Life of Mine were brilliant, and today, both movies still top lists of the most-acclaimed Chinese movies. [Source: Tristan Shaw, SupChina, March 1, 2019]

“1949 was an important year for Shi. He continued his box office success with “Miserable at Middle Age”, a comedy-drama starring Shi as a widowed principal with a special devotion for the school he’s been running the past decade or so. Shi also wrote and directed Mother that year, a social drama about a mother who’s left with only a son after her husband commits suicide and her daughter dies young. It was a competent enough debut, but the following year, Shi would make the masterpiece of his career, the epic biography “This Life of Mine”. Shi’s adaptation of this Lao She novella featured himself in the lead role, playing a kindhearted Beijing policeman who struggles to understand the political turmoil around him. Living his life from the last years of the Qing Dynasty to the end of the Chinese Civil War, Shi’s nameless cop does everything right, only to be repeatedly abused and left to die in the streets of the city he so long tried to protect.

“The ending of This Life of Mine is tragic, yet unabashedly pro-Communist, suggesting that better days were surely ahead for China. At first, Shi tried to get on the good side of the Communist Party. He did charity work for veterans, and helped lead a march of movie celebrities in favor of the PRC in October 1949. This Life of Mine was meant to be a tribute for the PRC, and Wenhua and Shi tried paying further homage with works like Spring of Peace (1950) and Platoon Commander Guan (1951). Unfortunately, both these attempts starring Shi were political misfires.

“The Hundred Flowers Campaign briefly loosened the Communist Party’s chains on the Chinese film industry. In his last role, Shi played a part in the 1957 movie Endless Passion, Deep Friendship . Meanwhile, he worked on a screenplay, a political allegory about the passengers on a boat called Democracy No. 3 trying to navigate through a thick fog. This ended up being Night Voyage on a Foggy Sea , Shi’s last piece of work.

“Like the satirist Lu Ban and other contemporary filmmakers, Shi became a target when the Anti-Rightist Movement erupted. In a struggle session, an unflattering party member in Night Voyage on a Foggy Sea was taken as an attack on the Communist Party itself. Nobody dared to risk their reputation defending Shi. Humiliated, Shi was sick of the treatment he had endured. On an unknown date in December 1957, Shi got onto a boat in Shanghai, jumped off the deck, and drowned himself in Huangpu River. During his “disappearance,” the film industry and critics continued to vilify Shi in the press. He remained missing until April 1959, when his body was finally found and identified. At the time of his suicide, Shi Hui was only 42.

For the entire article See MCLC List /u.osu.edu/mclc

.jpg)

Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai in 1954

Unfinished Comedy and How It Destroyed Its Maker

“The Unfinished Comedy” was how a brave Maoist-era satire that destroyed its creator’s career. Tristan Shaw wrote in SupChina: “In the 1957 satirical film The Unfinished Comedy, made during Mao Zedong’s Hundred Flowers Campaign, one of the characters is a CCP censor who initially ensures a comedy duo of his support, only to become increasingly irritated as their show goes on. The irony was all too real. [Source: Tristan Shaw, SupChina, January 25, 2019]

“During his very brief stint as a satirist, Lu Ban became one of Chinese cinema’s greatest — and shortest-lived — comedy directors. In the span of a year, between 1956 and 1957, Lu made three comedies satirizing life in Maoist China. The Hundred Flowers Campaign allowed Lu to poke fun at both ordinary people and even Communist Party officials, but when the Anti-Rightist Campaign quickly followed, Lu became an early victim in the crackdown. His third and most brilliant satire, The Unfinished Comedy ( méiy u wánchéng de x jù), was condemned by the Communist Party, and led to Lu being labeled a “rightist.” The movie destroyed Lu’s career, getting him outright banned from filmmaking.

“After the release of his second short in January 1957, Lu went into production of what would be his best and boldest satire, a feature-length work that ridiculed censorship: The Unfinished Comedy. The movie stars Han Langren and Yin Xiuzhen , a slapstick duo from the 1930s and ’40s, playing themselves. After tearfully reuniting at a train station, Han and Yin head to Changchun Film Studio (where the movie was actually filmed) to put on a performance of three comedy skits. Their audience includes a movie director, journalists, and a CCP censor named Yi Bangzi. Initially, Yi assures Han and Yin of his support, but as the show goes on, becomes increasingly irritated with them.

“Each of the three skits is presented on a stage. In the first episode, Yin plays a bureaucrat who takes a vacation in order to lose some weight. His assistant (played by Han) mistakenly believes that his boss dies during the trip, and decides to give him an extravagant funeral. In the second episode, Han and Yin try to impress a singer at a dancehall, while in the third they play a pair of sons who abuse and cheat their mother. Yi criticizes and hates all three skits, and after arguing with an audience member, leaves the studio. On his way out, Yi leaves through the back of the stage and bumps into a pillar, causing a beam to fall and hit his head.

“Needless to say, the Communist Party wasn’t pleased. The timing was also poor: The Unfinished Comedy was completed not long after Mao called off the Hundred Flowers Campaign, initiating a backlash against the “reactionaries” and “rightists” who criticized the Chinese government. The Unfinished Comedy was denied a release, and Lu was attacked in the press. In one article, the official who earlier approved the Spring Comedy Society denounced Lu’s movie as “thoroughly anti-Party, antisocialist, and tasteless.” Ironically, some of Lu’s detractors quoted Yi Bangzi to justify their criticism against him. In struggle sessions, he was accused of being a rightist, with screenings of The Unfinished Comedy being used as proof for the charge.

“For his “crimes,” Lu was banned from filmmaking. By the time he died in October 1976, The Unfinished Comedy remained the last movie he ever worked on. Despite its obscurity, Chinese film scholar Paul Clark has called The Unfinished Comedy “perhaps the most accomplished film made in the 17 years between 1949 and the Cultural Revolution.” Political bravery aside, it’s an interesting and funny movie, and Han and Yin are a pretty loveable duo. As a whole, Lu and his satirical trilogy deserve to be better-known, and I’m keeping my fingers crossed these movies will someday be released on home video or streaming with English subtitles.

For the entire article See MCLC List /u.osu.edu/mclc

Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy

Film During the Cultural Revolution

During the Cultural Revolution, the film industry was severely restricted. Most previous films were banned, and only a few new ones were produced. In the years immediately following the Cultural Revolution, the film industry again flourished as a medium of popular entertainment. Domestically produced films played to large audiences, and tickets for foreign film festivals sold quickly. No films were shot in the Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1972. Between 1973 and 1976 a handful of propaganda films endorsed by the Gang of Four were made. The films made then more or less reflected the real situation of China during the "Cultural Revolution".

Chris Berry, a professor of film and television studies at Goldsmiths University of London who organized a Cultural Revolution film series, told dGenerate films, some of the most interesting Cultural Revolution films capture a “the visceral thrill of political action, including violence, and how powerfully exciting this can be for young people, at the same time as it can make them vulnerable to being used and making mistakes. That’s why we chose Mao’s saying “A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire” for the film series. We felt it captured the sense of excitement and danger perfectly.

Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni’s made a trip to China in 1972 at the height of the Cultural Revolution to make the film “Chung Kuo — Cina” . The Chinese government expressed “disappointment” and displeasure with Antonioni’s depiction of China — even though he had been invited by the Chinese government, Premier Zhou Enlai specifically, to make the documentary. Chung Kuo was shown for the first time in China only in 2004. [Source: Ken Kwan Ming Hao, China Beat, October 20, 2010]

See Separate Article CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS — MADE ABOUT IT AND DURING IT factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021