IMPERIAL CHINESE ART OBJECTS

meat-shaped stone kept in a Curio cabinet

In Imperial times, luxury art and crafts were indications of status and there was a certain hierarchy among the individual crafts. Jade carvings and lacquerware were more highly esteemed than ceramics. Jade was especially prized because of it symbolic value and the fact it was difficult to carve. Chinese art objects possessed by emperors included carved and decorative ink stones; ru-yi scepters (scepters that symbolized political and military power that were given to dignitaries and courtiers on different occasions); and miniature curio cabinets (elaborate multi-compartment boxes for storing things). Highly valued objects were made from animal horn (rhinoceros horn was particularly prized), silk, jade, ivory, lacquered softwoods, and polished hardwoods.

Among the items the emperors kept in miniature curio cabinets were small combs, tea containers, censers, incense, small knifes, nail files, forks, tweezers, brushes, pens, books, ink slabs, ink, ink cases, paper, brushes, brushwashers, brush-racks, water containers, glue boxes, seals, seal ink, and carved decorative pieces made from bamboo, wood, enamel, bronze, porcelain, ivory, gold, silver, rock-crystal and jade. The tiny compartments, shelves, drawers and boxes were often connected in elaborate, cryptic ways.

Pei-chin Yu wrote for the National Palace Museum, Taipei:“The emperors of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) had many treasures in their possession. Some of these prized possessions were finely crafted and richly decorated utensils used for imperial court life, and some were simply for the emperor's enjoyment. All items from the Qing imperial collection, from richly enameled ceramics to watches and snuff bottles, represent the imperial lifestyle of the Qing. They are also an important sign of the on-going trade between China and the West.

“Revealed in the opulent shapes, sophisticated designs and beauty of the materials are the ingenious skills of the craftsmen that we can all still appreciate. Keep in mind that as each piece was handed down from generation to generation, each owner attached different meaning to the work. Also, the function of an item often changed to meet new demands, thus gaining new significance for each new era. [Source: Pei-chin Yu, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

See Separate Articles: CHINESE CRAFTS: BAMBOO CUPS, SEED CARVING AND PAPER CUTS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FURNITURE: TYPES, FUNCTIONS AND QUALITY MING AND QING PIECES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EMBROIDERY AND TAPESTRIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LACQUERWARE factsanddetails.com ; TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE GARDENS factsanddetails.com QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts /mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net; Crafts : Kites travelchinaguide.com ; Furniture chinatownconnection.com ; Furniture chinese-furniture.com ; Jade: Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; International Colored Gem Association gemstone.org;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Masterpieces of Chinese Miniature Crafts in the National Palace Museum” Amazon.com “Chinese Art Treasures; a Selected Group of Objects From the Chinese National Palace Museum and the Chinese National Central Museum, Taichung, Taiwan by Guo Li Zhong Yang Bo Wu Yuan, Guo Li Gu Gong Bo Wu Yuan, et al. Amazon.com; “Treasures From the Shanghai Museum 6,000 Years of Chinese Art” by Shanghai Museum Amazon.com “Chinese Objects of Art” by American Art Association and Anderson Ga American Art Association Amazon.com; “Chinese Art and Design: Art Objects in Ritual and Daily Life” by Rose Kerr Amazon.com “Elegant Life of The Chinese Literati: From the Chinese Classic, 'Treatise on Superfluous Things', Finding Harmony and Joy in Everyday Objects” by Zhenheng Wen, Tony Blishen, et al. Amazon.com; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Ming and Qing Crafts

In terms of the arts, the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) periods are known mainly as a time when traditional Chinese crafts and decorative arts reached a high level, producing some wonderfully intricate and beautiful pieces. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Imperial kilns of the Ming dynasty pursued the beauty of porcelain through various bright and lustrous colors. And the variations of glaze colors found in underglaze-blue, doucai ("Competing-colors") and wucai ("Five-colors") porcelains at the time undoubtedly stood out as the most innovative and advanced forms of kiln firing technology in the world, being objects of a practical nature with daily life aesthetics. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The Ming dynasty court also oversaw the production of such arts as carved-red and colored lacquerware, fully grasping the supple quality of lacquer and carving to reveal layers of colors. The enamelware from imperial workshops feature full and vibrant colors on thick metal forms, integrating this craft imported into China during the fourteenth century with local artistic traditions to create a new bright and beautiful art. The fashion of studio objects and curios also opened up various realms of marvelous inkstone, ink, bamboo, and stone productions, with many craftsmen achieving fame for their consummate skill. The pure and archaic taste of literati likewise became a guiding force in refined culture thereafter. Prize pieces include underglaze blue porcelain, cups with chicken in a garden scenery decoration doucai polychrome porcelain, carved red lacquerware.

“The Qing dynasty emperors attached great importance to the production of arts and crafts, with the court establishing imperial workshops to oversee the production of various carvings, inlay, porcelains, and embroidery. Gathering craftsmen from all over the land, extraordinary skill and ingenuity were the result. The objects include a crown, accessories, and seals of the Qing emperors. Songhua stone, from the homeland of the ruling Manchus, was skillfully carved into inkstones using innovative manners. Painted enamelware of the court also imitated tribute objects from the West, transforming them into skillfully integrated productions of poetry, calligraphy, and painting on bronze, porcelain, and glass. And skilled artisans at court could delicately carve a boat from an olive pit or paint a tiny snuff bottle with enamel colors, fully grasping their marvels of appreciation. Curio boxes were also used by the emperor for storing numerous small artworks in compartments that open and revolve or hidden in drawers and other specially designed spaces of ingenuity. These are all products of the imperial workshops that continue to fascinate viewers even today.

“Tribute objects from surrounding lands that were gathered at the court include Tibetan Buddhist implements and Islamic jades, which attracted the interest of and inspired Chinese artisans. Such artworks as a jadeite cabbage designed according to its colors and a handled ivory food basket carved as delicate as gauze are magnificent examples of craftsmanship that have been the focus of attention for many years. Among the most prized pieces are a evolving vase with swimming fish decoration, porcelain, with gold tracery on blue glaze, a set of nine 9 seals with animal knobs made from Tienhuang soft stone, a Four-tiered food carrying case carved from ivory and the famous jadeite cabbage.

Treasures of the Chinese Emperors

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““A Garland of Treasures” is the title given in the Qing dynasty by the Qianlong emperor to a curio box in his collection. As the name suggests, it means a group of small but precious artifacts. The cherished crafts in the collection of the National Palace Museum include enamels, clothing and accessories, studio objects, lacquerware, Buddhist ritual implements, carvings, and curio boxes. Covering a wide range of forms and materials, these artifacts are especially numerous and of high quality, revealing an important facet of the Qing imperial collection. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The collection of precious crafts in the National Palace Museum mostly derives from items used in daily life at the imperial court. Some were ritual objects and others diplomatic gifts. There are accessories that were used for ceremonial purposes, while others formed part of the dress and make-up for those living in the ladies’ quarters. Some crafts were displayed in palace halls, served as curios to be appreciated at leisure, or found in the scholar’s studio. Others are also rare collectibles stored in chests that were all specially designed and marvelously produced.

“The materials used in this eclectic grouping of crafts often include composition combinations, being mainly gold or silver, semi-precious stone, bamboo or wood, ivory or horn, and ink or inkstone. They are also skillfully integrated frequently with bronzes, porcelains, and jades, with many different materials often appearing together. And along with a mixture of different techniques, these objects truly reflect the diverse beauty of Chinese arts and crafts. As for the subjects to decorate them, they often interweave auspicious patterns, folk legends, and historical allusions, being profoundly steeped in the essence of Chinese culture to create a sense of dignity, elegance, and delight in life.

“Clothing, accessories, and other ornaments were an integral part of the ritual system in traditional society. These objects concretely reflect the material culture of different periods and trends in arts and crafts. The collection consists of various beautifully crafted accessories for personal adornment, the types numerous and the materials quite refined. Their workmanship masterfully combines fine techniques of metalworking, inlaying pearls and kingfisher feathers, carving in fragrant wood, and using gemstones. Their forms are likewise diverse and the decorative patterns rich and varied, conveying dignified opulence and refinement as well as exuberant vigor and allure. They fully evince the historical traditions inherited by the Qing court and the homeland of its Manchu rulers in the northeast, thereby giving rise to their unique cultural manifestation. Precious accessories and auspicious objects of the court, though often serving different functions, share many things in common, such as material selection, auspicious subject matter, and artistry, revealing the vibrant beauty of these court treasures and creative ingenuity integrating design and craftsmanship.

These treasures include: Cloisonné box with lotus decoration (Jingtai reign, 1450-1456, Ming dynasty); Cloisonné and painted enamel butter tea jar (Qianlong reign, 1736-1795, Qing dynasty; Gold mandala with turquoise inlay ( mid-17th century, Tibetan); “Cloisonné censer in the form of a wild duck Early 16th century, Ming dynasty); Gilt flint case with coral-and-turquoise inlay (with carved lacquer box and Qianlong reign mark); Pair of "Bovet" pocket watches with pearls and painted enamel (19th century); “Planter with a coral carving of the planetary diety Kuixing (Qing dynasty, 1644-1911); Agarwood bead bracelet (with tin storage container, Qing dynasty); Set of carved openwork concentric ivory balls with cloud-and-dragon decoration (19th century, Guangdong, Qing dynasty); Carved olive-pit pendant on the joy of fishermen in the shade of a pine (Chen Ziyun, 17th-18th century); Set of rhinoceros horn archer's rings with gold-and-silver filigree inlay (Qianlong reign 1736-1795, Qing dynasty); Refined clay “Chaoshou” inkstone used by Zhang Zhi (Song dynasty (960-1279); Carved ivory ruler-weight with hornless-dragon decoration (Qing dynasty; Rock crystal brush stand in the shape of a mountain (Ming dynasty, 1368-1644)

Sources and Craftsmen of the Chinese Emperor’s Treasures

Ivory Puzzle Ball

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Metalware was a craft reserved for the wealthy and upper classes in imperial China. Enamels, involving glazes painted and fired onto the surface of a metal body, became an important art form in the Ming and Qing dynasties. The enameling technique of cloisonné was imported from areas west of China, and domestic production began in the Yuan dynasty. It reached a peak in the Jingtai reign of the Ming dynasty, hence becoming known as “Jingtai blue.” In the Qing dynasty, the greatest advances appeared in painted enamels, especially at the courts of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors. European craftsmen during the Kangxi reign guided the imperial workshops, their achievements even competing with European painted enamels in beauty. Various enameling techniques were also combined in one work of art during Qianlong’s reign, fusing Chinese and Western decoration as well. Turning a glorious new page in the cultural exchange between China and the West, enamels serve as a symbol of national prosperity and artistic skills achieved under the Qing dynasty. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The Qing rulers, who traced their origins to the northeast, formed friendly relations with Tibetan and Mongolian peoples, exchanging precious gifts with them on a regular basis. The Buddhist ritual implements in this exhibit also represent the work of craftsmen from different areas in the Himalayan area, including precious tribute offered by leaders of the Yellow Hat sect of Tibetan Buddhism when presenting credentials or attending celebratory events. These objects thus testify to how the Qing court skillfully employed religious beliefs to hold together its large empire and maintain peace therein.

“The art of carving bears witness to not only a long history but also a variety of techniques, such as engraving, relief carving, openwork carving, and sculpting in the round. All have been used to decorate objects for daily life or display and appreciation. The materials also vary widely, including metal, jade, stone, wood, bamboo, ivory, bone, and horn, each of which can be carved. In terms of decorative subject matter, there are images related to auspicious symbols, historical allusions, and myths and legends. Combined with traditional forms and period styles, they express a rich and varied appearance. Actually, many of the carved objects from the former collection of the Qing court, including those of the scholar’s studio and pendants to be worn, had long transcended their original practical function to focus on choice materials, refined workmanship, and unique forms, thereby stressing instead the pursuit of refinement in life. Furthermore, artisans ingeniously conceived of and combined different art forms and techniques in carving based on the nature of materials, revealing the beauty of “seeking breadth and greatness but not overlooking exquisiteness and details” when the viewer appreciates these objects at leisure. Thus, these works often make viewer want to exclaim, "Oh, how divine the skills of all these craftsmen!"

“The studio was the center of life for the traditional scholar, and such utensils on the long table there included brush, inkstone, paper, and ink in addition to water pourer, brush stand, paperweight, and others. Not only used for writing, these utensils that accompanied scholars throughout the day naturally became objects that reflected their aesthetic taste and appreciation. Inkstones, for example, are generally divided into those made of ceramic and stone, the material chosen to grind ink without damaging the brush hairs. Song dynasty inkstones are often made from refined clay or Duan stone, being mostly in the "Chaoshou" rectangular form. Starting from the Ming dynasty, the shapes of inkstones became much more varied, with great attention placed on the production of covers. The user’s name and inscriptions by collectors were also engraved on the sides of inkstones to express a yearning for the past. A fondness for antiquity among scholars led them to increasingly select bronzes of the Shang, Zhou, and Han dynasties as inkstone drippers, water pourers, and paperweights. Scholars also chose white Ding porcelain, crackled Ge ware, and beautiful jade and stone materials to serve as brush washers, pots, and stands. Objects of many different materials consequently found their way onto the scholar’s table, combining archaic elegance with lyricism emanating from the brush. The studio, however, would not have been complete without other furnishings, such as a bronze or porcelain incense burner and flower vase to create a fragrant atmosphere. And when the mood struck, the scholar would often open an elaborately conceived chest to leisurely appreciate a collection of precious curios from different periods and places, thereby complementing the setting and atmosphere of the studio.

Curio Cabinets

Pei-chin Yu wrote for the National Palace Museum, Taipei: As indicated by their name, to-pao-ko or miniature curio cabinets are used to collect and store a great variety of different miniature treasures and curios. Although there can be no certainty as to the source or date when these miniature cabinets first originated, in the surviving writings of prominent figures living in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644 A.D.) it was recorded that literati-scholars of that period customarily prepared a type of all-purpose convenience kit for use when traveling or staying out overnight. Inside these kits were arranged small comb cases, tea containers, censers, incense boxes, bottles for incense accessories, etc. Also included were small travel cases containing items that might be needed on a journey, such as a small knife, nail file, fork, tweezers, etc.[Source: Pei-chin Yu, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Many of the miniature curio cabinets in this museum's collection originate from the Ming dynasty imperial palace collection. In this exhibit the miniature lacquer curio chest with carved cloud-and-dragon decor and inscribed fu-lu-kang-ning (Wealth, Happiness, Health, and Tranquillity) be aring the Chia-ching seal-mark is an example of a work deriving from this period. Many of the other works in the Palace Museum collection were tribute-gifts presented to the emperors by their subjects or from visiting foreign envoys; as represented by the gold-lacquered boxes displayed in this room. The Museum collection also contains many works produced by the Qing impenal workshops, as well as many works produced under imperial auspices at various localities (e.g. Yangchow) emulating court designed blueprints.

Qing curio cabinet

“The term to-pao-ko includes a variety of cleverly-constructed small cabinets, cases, chests, and boxes in which the greatest number of objects were designed to be arranged in the limited space available. The designers also tried to make them as interesting and esthetically stimulating as possible, so that within a single to-pao-ko one often finds an intricate array of tiny compartments, shelves, drawers and boxes, sometimes one inside another or interconnected in mesmerizing ways. In some cabinets, a whole new area can be discovered behind what appears to be a blank wall by simply turning a knob. Despite their diminutive overall size, these cabinets can thus contain dozens or even hundreds of curios, and it is often difficult to find all of the items secreted within. Such miniature curio cabinets are therofore masterpieces of skillful craftsmanship in themselves, quite apart from the delightful miniature objects they contain.

“Because of the Qing emperors' great fondness for these works, most of the miniature curio cabinets now in the Museum collection were originally kept in the Yang-hsin Tien, Ch'u-hsiu Kung, and Ch'ung-hua Kung, palaces of the imperial complex (the Forbidden City in Peking); these were the actual resideces of the emperors and empresses, and were where they spent their leisure time. The thirty-four works selected for display in this exhibition reveal the great variety in size, design, and material characterizing miniature curio cabinets; standard square, round and rectangular can be found along with large standing cabinets, interconnected cases, cabinets shaped to resemble books, etc. They are presented here to provide our visitors with a glimpse of this uniquely Chinese craft, the product of patient and skillfull design and labor.

Objects Kept in Curio Cabinets

Pei-chin Yu wrote for the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The objects placed in these to-pao-ko are also rich in variety, and included items of bronze, porcelain, jade, ivory, enamel, and glass as well as works of painting and calligraphy. Each object had a compartment specially designed for it; jades and ivory carvings are housed in drawers or boxes, while small painting-scrolls, books, and fans are placed in internal compartments and cases. The scrolls of painting and calligraphy were executed by court artists on a miniature scale, and such items as the little brush-racks, water-droppers, and other literary paraphernalia were small replicas of their larger counterparts. [Source: Pei-chin Yu, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The early years of the Qing dynasty were a period of peace and prosperity for China; her national strength was at a peak, and scholarship and the arts flourished. The emperors of this period, including the Qianlong emperor, were especially devoted patrons of the arts, and avidly collected not only painting, calligraphy, and ancient bronze vessels, but were also much enamored of skillful craftsmanship in bamboo, wood, ivory, and bone as well as in gold, silver, rock-crystal and jade. Natural objects of strange designs and textures also pleased them, and they amassed collections of extraordinary wealth and variety. Not surprisingly, high and low court officials vied with one another to find rare and beautiful curios for the emperors' enjoyment, while foreign envoys outdid each other in bringing small treasures from their native lands to the court as well, thereby yielding large numbers of beautifully crafted curiosity-pieces for the palace collections.

“Literati-scholars in the Ming dynasty were for the most part very particular when it came to their writing tools and other essential literary items, which, they collected together inside stationary cases. In some stationary cases there were arranged thirty or more different types of small literary accessories such as brushes, pens, books, ink-slabs, ink, ink cases, paper, brush-racks, brush-washers, water containers, glue boxes, incense accessories, seals, seal-ink, etc. Clearly these convenience kits and stationary cases, popular in the Ming dynasty, were the prototypes of the later Qing dynasty (A.D.1644-1911) miniature curio cases.

Curio Boxes

Curio boxes, known as "to-pao ko” (“multi-treasure compartments”) were like curio cabinets but smaller and today are sometimes referred to as "imperial toy chests". Tsai Mei-Fen wrote in the Taiwan Today: “Curio boxes are specially designed cases with various compartments, levels and drawers that are used to store many kinds of small art objects in a convenient, rational manner so that they can be carried and appreciated anywhere. This kind of case has its origins in antiquity and derives from those used for brushes, studio objects, combs, travel items and perfume among the higher classes of society. Considerable effort was often paid to the design and production of such boxes so that they would complement the valuable contents contained therein. Great ingenuity was employed to make the most out of the smallest of spaces. Often a single level would be divided into several sublevels, or compartments subdivided into several smaller ones. Sometimes a compartment would hold drawers, and vice versa. At other times, hidden compartments would be cleverly incorporated into the piece that required a special method of opening and closing. All sorts of techniques were required to access the objects contained inside, such as pulling, pushing, lifting and unhooking certain parts of the box. Indeed, the crafting of a curio box can be called the art of designing space, much like interior design, where almost anything is possible. Compared with the makeup box of the West and ink stone cases of Japan, there is much more than meets the eye when it comes to the curio boxes of China. [Source: Tsai Mei-Fen, Taiwan Today, April 2009. Tsai Mei-fen is a curator at the National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“Although it is said that expert craftsmen in many places of the southern area of the Jiangnan region were already producing this type of curio box during the late Ming dynasty (ca. 16th-17th centuries), many of the most beautiful curio boxes in the museum's collection were made under the supervision of the Qing dynasty court. On the one hand, the Qing court focused on the exterior appearance of the boxes, instructing craftsmen to construct new ones of carved sandalwood, porcelain inlay, bamboo appliqué and openwork mother-of-pearl, with exteriors decorated with lacquer, gold highlighting and paint. Antique cases and Japanese lacquered boxes were also converted into curio boxes.

“Square Sandalwood Curio Box with Cloud-and-dragon Décor” from the Qianlong era (1736-1795) in the Qing Dynasty contained 47 curios and was 16.5 centimeters tall, 30.3 centimeters wide and 30.5 centimeters long. “One of the most attractive and unique features of curio boxes is the special attention placed on an "interest in playfulness". The design of a curio box is often prized for its clever construction, and surprising twists and hidden compartments are all part of the appreciation. In fact, the concept behind the curio box is somewhat akin to that of a "hide-and-seek" game, in which one is always discovering something new or surprising.

“Sandalwood curio box with carved dragon décor” dating to the Qianlong era contained 47 curios and measured 35 x 21.5 x 44.6 centimeters.“According to archival records, this curio box was filled with objects around 1747 during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor and used specifically as a carrying case on imperial trips. There is also an album leaf of "Extract of Rhymes by a Dilatory Brush" written by the Qianlong Emperor's son, the Chia-Qing Emperor, indicating that the box was passed down and its contents added to or changed over time. As opposed to walled display-type curio boxes, or curio boxes with treasures in fixed places at court, this small case, because it was meant to be transported, had to be designed with convenience in mind while also protecting the treasures inside, resulting in its sturdy construction. The focus of its design is a tray-within-a-tray system of tiers. The treasures inside date as far back as 5,000 years ago, and their source locations span great distances and cultures, ranging from a Neolithic period ts'ung-type tube of eastern China to the most fashionable painted enamel pocket watch at the time from Europe.

Contents of the Curio Boxes

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Most prized objects were stored in "curio boxes", while those of lesser grade were placed among "a hundred assorted items" and even further down in "treasure chests of ten thousand". In addition, curio boxes were often designed with certain effect in mind, allowing pieces to yield interaction with others or become reciprocally complementary. This method adds to the practical and convenient use of the limited space. It also gives the meaning of "combination' even more profound connotations that give equal consideration to material and spirit. The pragmatic and the emotions are both emphasized to accommodate a world within a world! [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

A myriad small objects was kept inside the curio boxes. Tsai Mei-Fen wrote in the Taiwan Today: “Ranging from those made in antiquity down to the time the curio boxes themselves were constructed, these small treasures include cleverly arranged Neolithic period jade ornaments, Western enamel painted timepieces, small Japanese lacquerware items, and rare Chenghua period docai polychrome cups. In the archives of the Qing court, there are many references to the emperor's personal instructions as to which objects were to be placed in the boxes. He sometimes ordered craftsmen from the palace workshops to create miniature works of porcelain, bronze and jade — and even scrolls and albums containing paintings — that would fit into the boxes, resulting in a dazzling display of myriad forms, colors and materials. [Source: Tsai Mei-Fen, Taiwan Today, April 2009. Tsai Mei-fen is a curator at the National Palace Museum, Taipei]

The source and date of the engraving bronzes, ceramics, jades, and other such objects kept in the boxes was often difficult to ascertain. Apart from the imperial reign mark made as part of the artifact at the time of production, collectors seldom added engravings on antiquities in their possession. Starting from the High Qing dynasty, however, craftsmanship techniques and human resources reached a pinnacle. Not only were seals and inscriptions engraved on the surfaces of antiquities in great numbers, sometimes entire passages and poems were articulately carved to clearly record the precious collection of the imperial family.

Jadeite Cabbage, the Meat-Shaped Stone and Jade Squirrels

The famous meat-shaped stone of Qing dynasty (1644~1911) in the collections of the Museum is a quartz curio of jasper chalcedony. The bands of layered textures formed by the infinity of Nature are further processed by the ingenuity of Human: tight tiny holes pose as pores and also serve to prime the grain for easier dyeing. The brownish red dye "marinates" the rind in soy sauce, adding a finishing touch in the transformation of a hard, cold stone into this piece of tender, juicy, melting-right-in-mouth Dongpo pork. What a humorous pact and collaborative act between Nature and Human, a wonderfully smart carving it is. The Meat-shaped Stone, on a metal stand is 5.3 centimeters long, 6.6 centimeters wide and 5.7 centimeters high

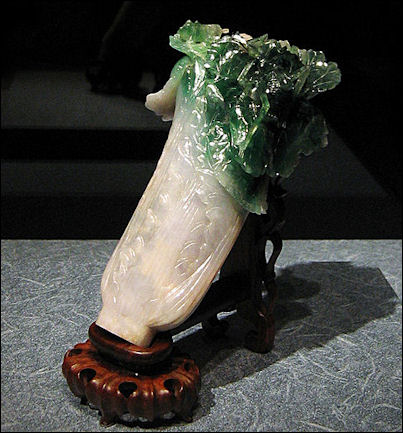

Qing period Jade cabbage

Other interesting Qing Dynasty pieces (1644~1911) include 1) “Jadeite Squirrels and Grapes, on a wood stand (7.2 centimeters high and 5.1 centimeters wide); 2) “Jade Boy and Bear: (6.0 centimeters tall); 2) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene; 3) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene (5.1 centimeters wide; 5.9 centimeters tall); and 4) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a scene of triumph” (5.3 08 wide; 6.7 centimeters tall)

On its famous jadite cabbage, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “This jadeite, part green and part white, which is now a wonderful Chinese cabbage, would be considered mere second-rate material full of impurities if it was to be made into usual vases, jars, or ornaments, because of the cracks and blemishes that came with it. However, the artisan ingeniously transformed the rock into a lifelike vegetable of leafy green and white stems, with all unappealing rifts now hidden invisible amid the veins. And the discolored spots take on the marks of snow and frost. So with a stroke of genius, defects turn perfect. Beauty is in the detail and creativity works wonder. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The cabbage used to be a curio item displayed in Eternal Harmony Palace, the residence quarter of Emperor Guangxu's Lady Jin. For this reason, the piece is thought to have belonged to her. Hence the inference that the "white" cabbage signifies purity or chastity of the bride, and the two insects alighting at the tips of leaves symbolize fertility: bringing a long line of imperial children to the royal family. In addition, there is a pleasant surprise in this exhibit for our visitors: the original setup of the cabbage while it adorned the Qing palace is now reenacted through a video image. It shows that the cabbage was previously "planted" in a cloisonné flowerpot as a potted landscape, quite a fancy and interesting way of display. The Jadeite Cabbage, in a cloisonné flowerpot is 5.07 centimeters long, 9.1 centimeters wide, and 18.7 centimeters tall.

See Separate Article JADE AND CHINA: OBJECTS, SOURCES, MINING, ARTISTRY AND SPIRITUALITY factsanddetails.com

Ivory Carving in China

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““Hunters and fishers of Paleolithic age already learned to make use of the inedible parts of their game and work these into simple tools or ornaments. Ivory went on to become an integrated and widely used component of Neolithic craft cultures, often made into items of ritual and religious purposes. Following on the spread and advancement of civilization, however, the elephants and rhinoceroses which used to roam over China Proper in remote antiquity retreated from basins of the Yellow River and the Yangtze River. [Source: Jo-hsin Chi, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Bronze was the crux of the Shang culture (1600~1046 B.C.) but significant progress in ivory carving also appeared at the time. The Shang craftsmen not only worked the intrinsic nature of the material, they also enhanced its beauty with semi-precious stone inlay such as turquoise. Fast forward into Yuan dynasty (1271~1368), the royal house often decorated their palaces with ivory, thus leaving little for other private use outside the court. Lack of materials led to the decline of the art. Ivory carving went downhill as a result.

“After the mid-period of Ming dynasty (1368~1644), the activity of carving as an art and craft was concentrated in the Wuzong area. But ivory carving was not a specialty on its own in the region. For a skilled enough carving artist, though, his capacity was never limited. Even famous bamboo carvers could work on ivory as well. Into Qing (1644~1911), bamboo carvers who served at the court in the Workshops of the Imperial Household Department, such as Shi Tianzhang and Feng Shiqi from Jiading, were also ordered more than once to create ivory works and with astounding results. Their rank at the royal workshop was accordingly promoted to that of Imperial Ivory Artisan.

“Academically, the Qing ivory carving is categorized into two schools: Beijing-based North Style, including both private-owned and court-run ivory workshops, featuring ivory in its natural attributes and stressing polished textural effects; and Canton-centered South Style, thus also called Canton Style, which focused on carving prowess and bleached their ivory white. Resulted works were luminously white, the knife's work showing and showy, exquisitely and intricately wrought. Above it all, ivory floss weaving was Canton artisans' one-of-a-kind, extraordinary masterpiece. The Beijing's Imperial Ivory Workshop had a sobriquet for the South School's four unique specialties (linked chains, "live" openwork or "animated" patterns, floss weaving, and the layered concentric ball): "Celestial Feat".

“The eighteenth century's Imperial Workshops assimilated carving styles from the early High-Qing's Suzhou of Jiangnan, and incorporated the North School on the foundation of Canton's ivory carving techniques. It joined the best of both schools; and under the patronage of the emperor and dictated by his royal taste, the court artisans created a very unique courtly style for ivory carving. The designs were a good mix and use of elaboration and restraint. Where motifs were intricate and rich in detail, knife work was the focal point. When simple designs were intended, smoothest possible grinding and polishing were emphasized. Finally, highlighting with dyes in appropriate spots added an imperial, stately touch. The court artisanship thus led the nation in ivory carving until the dynasty was over.

Chinese Ivory Carving Masterpieces and Craftsmen

“Ivory Miniature Dragon Boat (In a Chicken-shaped Lacquer Case)” was made in the 18th century. It is 3.6 centimeters high and 5.0 centimeters long. Jo-hsin Chi wrote in for the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ Multiple small chunks of ivory make up this miniature boat. The bow is in the shape of an erect dragon head; the three-storied cabin is complete with doors and windows which open and close nimbly. Eight oars project from each side of the boat; railings, ceremonial arches, and corridors stand on the deck, along with sixteen triangular flags and one canopy. A compact Japanese lacquered case provides storage. [Source: Jo-hsin Chi, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“During Qing, the boat and its case were kept in one of the two ancillary buildings to Yangxin Hall (Hall of the Cultivation of the Mind): Huazi Chamber or Yanxi Chamber. When the Palace Inventory committee went in and cataloged the piece in the morning of September 24th, 1925, the storage case was written down as the main item: "Gold-lacquered Chicken Case", and with a note indicating "one carved ivory boat inside."

“Today, the boat has acquired its own identity in the Museum's master catalog and both items are given their own numbers. The appealing chicken case was very likely of a Japanese import, and the intricate dragon boat was done domestically by one of the court's ivory artisans from the South, a quite prefect match for each other.

“Ivory Four-tiered Food Carrying Case in Openwork Relief” was made on the second half of 18th century to early 19th century. It is 45.4 centimeters tall, 30.4 centimeters long and 21.6 centimeters wide. The multi-tiered carrying case comes with a square handle, the long arms of which extend from the top, down to the bottom along the side of the four tiers of top-load drawers. The first three drawers can be removed, while the bottom one is fixed to the handle, and its height is less than those of the other tiers (3.5 centimeters versus 8.8 centimeters high). Each tier is slipped on the next through a mother-and-son-cap lid. The lid's knob is in the shape of Buddhist treasure vase or urn (one of the eight sacred auspicious signs collectively called Ashtamangala). The matching wood stand with an indented waist is decorated around with green-dyed ivory openwork insets, some of which have come off, however.

“The lid, the sides, and the drawer bottoms, all are of super thin ivory panels in delicate, exquisite openwork, and set into framing grids. Eight carved strips of red and blue radiate from the center of the lid where the knob is, down the entire length of the carrying case, dividing both the lid and the case into eight sections per tier, while each tier bottom is separated into seven unadorned borders. The side panel insets are carved in fine detail with landscapes, people, birds, animals, plants, and houses of varying motifs for highly enjoyable perusal. The tier bottoms and the stand insets are both in pierced carving of intertwined, stemmed flowers. The tier bottoms are further adorned with various patterns of pierced rosettes, each in its unique, ingenious manner. And that's not all. The intricate designs on the lid and sides are further set against a lacelike openwork ground of lengthwise fine lines. The delicate images and lines give the whole case such a fragile look that one dares not to touch with any degree of force.

“The lid knob in the shape of a treasure vase is also pierce-carved with stylized designs and dyed ribbons. As for the very long handle, it is full of auspicious signs and symbols, figures, flowers and fruits for longevity and happiness, each of which is dyed according to its kind. The key motif is the Eight Immortals, four on each vertical arm of the handle, soaring and flying in their respective otherworldly way amid clouds in the fairylands. Across the top part of the handle are eight hovering bats, four on the right and the other four on the left, together facing a round character of "longevity" in the middle. Clouds float around the character and the bats, and a frame of twisted-strand pattern in low relief surrounds it all.

“The entire carrying case and designs on it are intricate and exquisite beyond description: the dyes are colorful yet elegantly subdued. The flower-patterns are varied; human figures are diverse (immortals, fishermen, acrobats, etc). The birds and animals are of all kinds (horses, bulls, deer, mythical lions, and auspicious unicorns), and aside from ivory-white, the colors range from red, blue, yellow to green, purple, and brown.

Carved Ivory Puzzle Ball

“Carved Ivory Puzzle Ball: is one of the most amazing pieces at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Decorated with cloud-and-dragon motifs, it is comprised of 21 independently-moving concentric ivory spheres within the outer sphere of ivory. Produced during the Qing dynasty, it is made from a single, unbroken piece of ivory.

According to Digital Taiwan: The ivory sphere was carved from a single solid piece of elephant ivory to form successive openwork spheres inside, serving as either a hanging or resting decorative piece. From the inside to the outer layer, this type of sphere carving consists of several levels of openwork to form concentric balls, the diameter of each differing slightly from the preceding one. With each sphere nestled perfectly within the next, they form what appears to be an ordinary ball. However, each unit inside can move freely, demonstrating the ingenious and precise level of engraving by the artisan or artisnas.

Chinese puzzle ball, sometimes known as a devil's work ball, are made from a single solid ball with conical holes drilled in it, with the carver separating the different spherical shells using L-shaped tools. 3D imaging using computational tomography has been used to identify details of the manufacturing process. They were traditionally made of ivory. Following the international ban on the ivory trade, manufacturers of puzzle balls have tried using other materials, including bone. [Source: Wikipedia]

Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China

Rhinoceros horn cup in the National Palace Museum, Taipei

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Today rhinoceroses no longer roam around on the landscape of China Proper along the lower region of the Yellow River. However, once they were very active during the prehistoric times in both northern and southern parts of China. Over the recent years archaeologists have found relics of rhinoceros bones in various Neolithic sites. The aptly named Warring States period (475 — 221 B.C.) had a pretty huge demand for armors made of rhinoceros hide. By the time of Qin (221~207 B.C.) and Han (206 B.C.~ 220 C.E.) dynasties, this large, thick-skinned, herbivorous mammal had already become a rare sighting in the north. At the latest in the late West Han period, the beast was totally gone from the area of Guanzhong, where the imperial seat of power was. [Source: Jo-hsin Chi, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Back in antiquity, rhinoceroses roamed in the Yellow River valley but the number dwindled with the time as the region became unfitting for their existence. Down to Tang dynasty, wild rhinoceroses could still be seen in the mountainous areas in the southern China. Once into Song, however, as a whole the rhinoceros became extinct in China Proper. People accordingly knew less and less about the beast's physical attributes yet their needs for its horn never went less. Import was the only source for this rare material which could be used as medicine as well as for carving. Vessels carved out of the rhinoceros horn were appreciated by people from all walks of life and deemed valuable collectibles. Ming and Qing literati repeatedly extolled them in their writings; even the royal house joined the praising crowd. The present cup is one of such court items. What Qianlong said in his verse indicated that the emperor associated the piece with the craft tradition of Xuancheng, Anhui Province.

“The ever scarcity of the animal rhinoceros in Tang dynasty (618~907) made its horn ever precious. The Tang dress code required that the emperor and the crown prince alone could use hairpins made of rhino horn to fix in place their imperial crowns, and the officials wear rhinoceros waistbands according to their ranks. The horn remained an exotic rarity after Tang dynasty, and all the while people gradually became totally ignorant of the physical animal itself, except the faint knowledge that it had horns either on the head or at the snout. So the horn became the focal point in any paintings about rhinoceroses. Even as late as in 1674 when the Jesuit missionary Ferdinand Verbiest compiled an illustrated World Geography for Qing Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722), he portrayed India's single-horn rhinoceros in Volume II but did not identify it as such with its usual Chinese appellation xi (rhinoceros), calling it a "Nose-horn Beast" instead.

“Sumatran and African rhinoceroses come with double horns, one on the snout and the other at the forehead, whereas Indian and Javan rhinoceroses have just single horns. The horn is actually a keratinized layer of the rhino's nose skin, and considered a precious ingredient in Chinese medicine. The typical carved horn vessels are cups made from the tapering part of the conical horn, with a somewhat triangle opening. The patterns are usually a mix of low and high relieves, yet seldom carved through. Other forms and functions include raft-shape cups, small flower baskets or stands, little round boxes, and thumb rings for archers.

“Most of rhinoceros horn cups available today come from Ming (1368~1644) or Qing (1644~1911) dynasties. Despite the numerous praises and mentions in Ming literati's notes of the cups, that the material was hard to come by was perhaps the very reason that there were no artisans devoted to this single art alone. Qing Emperor Qianlong (1736~1795) did not just write poetry in praise of the existing rhino horn cups made from the times before him, but also ordered his workshop to make new ones in his own name and his time. Having collated, studied, and appreciated antique cups he already owned, Qianlong were now ready and he wanted his new cups to look like the old. The engraved inscription in Li (clerical) script that reads "Great Qing, Qianlong, In Antiquarian Style", shows very much the playful "antiquarian" side of his!

Chinese Rhinoceros Horn Cups

“Rhinoceros Horn Cup in the Shape of a Lotus-leaf” was made in the late 16th to early 17th century. It is 7.6 centimeters tall and 14.2 x 10.2 centimeters in diameter at the mouth. Jo-hsin Chi wrote in for the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The lotus-leaf cup is fashioned out of a rhinoceros horn, with the tapering tip section removed and the inside gouged out. The leaf rolls up and inwards, veins in low relief covering both sides. The outer side is further adorned with flowers, lingzhis (Ganoderma lucidum), and mountainous rocks in high relief carving, with one stem of two flowers extending into the inner wall: one in bloom tilting sideways, the other still a bud. The steep, protruding rocks and lingzhis together approximate a handle for the cup. The entire cup is dark brown, with a black bottom. [Source: Jo-hsin Chi, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Chinese has valued rhinoceros horns since antiquity as a rare material. The Han's Classics of Odes written in West Han dynasty told that when way back in the ancient late-Shang dynasty, the wise, old advisor Jiang Taigong to the Zhou state sent General Nan Gongshi east to a remote state Yiqu for the Horn of "Scaring off Chickens", to be presented as a gift to the infamous monarch of Shang. A passage from an ancient collection of fantasy tales states that the remote country (in today's Viet Nam) "Feile's tributes of rhinoceros horns reflected with a mix of glitter and shade (so the name: "shadow rhino"). When woven into seating or bed mats, it looked like beautiful rich-patterned brocade." The literatures indicate that the ancient people treasured the horns and regarded them as rare materials. Into Ming dynasty, the rhinoceros horn was valued even more because of its medicinal properties. It was also believed that vessels made of rhino horn could detect poison. The Ming literati wrote adulatory or poetic little verses about these elegant, sometimes wondrous objects. For example, a late-Ming Confucian student Wang Daokun (1525-1593) once composed an epigram of four phrases, each with three characters, for a rhinoceros horn cup carved into the shape of a lotus leaf, "Scoop of Nectar, Into the Lotus; Best to You, Long Live Forever", i.e. the rhino horn cup was used to drink a toast for wishing a happy birthday of longevity. He had another one composed for another rhino horn cup in the shape of hibiscus, "a Rhino Horn Cup, For Your Elegant Banquet; My Heart as Faithful, Yours as Bright Day".

“Rhinoceros Horn Cup Depicting the Land of the Immortals” was made during the Qianlong period (1736-1795), Qing dynasty. It is 9.9 centimeters tall. The slightly oval cup is made of a rhinoceros horn, with a flaring mouth and deep inside. It is wide at the top and narrows down to the flat, black bottom, revealing somewhat chipped damage along the light brown mouth rim. Below the rim, it is all dark brown. Fairy mountains and dwellings cover the entire outer surface, with clumps of trees here and there, and groups of immortals engaged in profound spiritual discussion. On the narrower side of the cup, protruding mountainous rocks and trees are carved in high relief and meant for the cup handle. Inside the mouth rim, on one side, a front-view dragon in relief coils amid floats of drifting clouds. On the opposite side is engraved in gold-filled intaglio six characters in Li (clerical) script, "Antiquarian Style, Qianlong of Great Qing". On the bottom is the emperor's four-line poem also in yinke (intaglio), in Kai (regular) script, dated "Qianlong, Xinchuo Year, Imperial Poem", which was 1781, the 46th year of his reign. The legend of the Zhuan (seal) script seal reads: "Antique Aroma". The royal verse is included in the emperor's anthology. The custom-made brocade wrap and case are still in existence, with a label affixed to the case cover, "one Rhinoceros horn cup depicting the Land of the Immortals inside".

“The matching wood stand of the cord-weave pattern is raised all round the side, so the cup could sit snugly and secure in place. The same verse and signature by the emperor and inscribed on the cup are also carved in gold-filled on the bottom of the stand, only in different styles of scripts. The impression of the seal, different too, reads "As Virtuous".

Franz Lidz wrote in Slate: “The appetite of Chinese collectors is so prodigious that rhinoceros-horn drinking cups that once sold for a few hundred dollars are now commanding hundreds of thousands of dollars. At a taping of Antiques Roadshow in July 2011 in Tulsa, Okla., Lark Mason, an expert in Asian art, valued a set of late 17th- or early 18th-century rhino mugs at between $1 million and 1.5 million, the highest appraisal in the program’s history. The owner told Mason he had been collecting the cups since the ’70s and was clueless about their worth. “I was hoping the guy wouldn’t collapse,” Mason recalls. [Source: Franz Lidz, Slate, April 4, 2012]

Inkstones

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Brushes, ink, paper, and the inkstone are the "four treasures of the studio." Scholars have relied on the these as their principal tools, whether for writing or painting, from ancient times to the present day. They are the Chinese people's unique invention, and after several thousand years of existence, countless writers and artists have used them to achieve countless works of literature and art. [Source: Jo-hsin Chi, National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Materials discovered in archaeological excavations show that inkstones were made even during the Neolithic Period. Tools for grinding pigment, the ancient prototypes of inkstones, have been found in Shaanxi Province, at the Chiang-chai site of the Yangshao culture. Tuan stone and she stone were discovered and adopted for use during the Tang Dynasty(618-907), taking Chinese inkstone carving into a Golden Age. Scholars of this period began to advocate the use of high-quality stone, and the technology for making inkstones advanced rapidly.

“The inkstone catalogue is a special type of Chinese literary work, which became popular among scholars during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Dozens of inkstone catalogues were compiled, becoming standard references for future scholars. The Yen-p'u (Inkstone catalogue), written by Ou-yang Hsiu is a brief 700 characters long, but nonetheless it describes the source, appearance, and quality of Tuan stone, She stone, Qing-chou golden purple stone, red-veined stone, Hsiang-chou ancient roof-tiles, and more.

Traditionally, the tuan stones of Guangdong, she stones of An-huei, t'ao-ho stones of Gansuh and red ribbon stones of Shandong were the prestigious. Inscriptions found on inkstones from the reign of Kangxi are numerous, ranging from the standard imperial reign mark ("Year of Kangxi") to various laudatory imperial seals. Longer and more elegant inscriptions praising the quality of the stone, such as "Used in tranquility, this inkstone will last lifetimes," are also common. The decorative motifs found on Kangxi inkstones often depict traditional and classical patterns. A fish fossil or a small window of glass is often used as a lid, and shells likewise are inlaid on the ink pool. Shapes of inkstones themselves vary greatly, taking square, circular, oblong, and rectangular forms, while ink boxes take on more adventurous non-geometric shapes such as fish and magnolia.

Imperial Chinese Snuff Bottles

Tsai Mei-Fen wrote in the Taiwan Today: “The snuff used by the Qing court was made from an aromatic herb and employed to lift the spirits. After snuff was imported into China during the early years of the Qing dynasty, it became popular among members of the imperial family, as well as among Tibetans and Mongolians. After being imported in large boxes, snuff was often repackaged into small bottles commonly employed as a convenient medium for storing medicine. Later, many kinds of precious and exotic materials — including gold, silver, porcelain, jade, agate and semi-precious gems — were used to make bottles specifically designed to contain snuff. However, the Qing court's favorite type of snuff bottle was made of glass. The workshops at the court produced various types of clear and colored glass, and they also developed techniques to combine layers of glass with different colors that could then be carved into beautiful patterns in an overlay technique known as "Peking glass." In another technique, fine brushwork was used to paint lustrous enamels on white glass snuff bottles. Accompanied by an ivory spoon and glass stopper, these bottles are masterpieces of the palace workshops. By the late Qing dynasty, a technique had even been developed for painting the inside of snuff bottles. Known as "inner painting," this technique gained widespread popularity. [Source: Tsai Mei-Fen, Taiwan Today, April 2009. Tsai Mei-fen is a curator at the National Palace Museum, Taipei]

Snuff bottles in the National Palace Museum, Taipei collection of European origin include: 1) Chased gold mechanical automaton musical snuff box (Joseph-Etienne Blerzy, circa 1775, France, 7.3 x 5.5 x 3.8 centimeters); 2) Gold agate-inlaid snuff box (James Cox, latter half of the 18th century, England, 7.7 x 6.15 x 4.25 centimeters); 3) Gold-body painted-enamel bordered musical snuff box with clock mounting (Circa 1785, Switzerland, 8.4 x 6.0 x 3.2 centimeters); 4) Silver gem-inlaid lacquered snuff box (Circa 1767, France, 7.4 x 4.0 centimeters); 5) Copper jointed fish-shaped box (Circa latter half of the 18th century, Europe, 13.3 x 2.6 centimeters); and 6) Gold-body painted enamel bottle with clock mounting (18th century, Switzerland, 7.3 x 3.2 x 1.2 centimeters). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Snuff bottles in the National Palace Museum, Taipei collection of Chinese origin include: 1) Copper-body painted enamel snuff bottle with a maki-e floral lacquer inlay (Kangxi reign, 1661-1722, 7.6 x 5.4 centimeters); 2) Coral snuff bottle in the shape of a bamboo segment Qing dynasty, 1644-1911, 4.9 x 2.6 centimeters); 3) Copper-body painted enamel snuff bottle with rabbits and multicolored clouds on a black background, Yongzheng reign, 1722-1735, 5.9 x 4.5 centimeters); 4) Jade flat snuff bottle with a dual ''chi''-dragon shoulder design, Qianlong reign, 1735-1796), 5.2 x 3.8 centimeters); 5) Chalcedony gourd-shaped conjoined snuff bottles (18th century) 6.6 x 5.2 centimeters; 6) Turquoise snuff bottle in the shape of a partially opened pomegranate (18th century, 6.3 x 5.0 centimeters); 7) Amber snuff bottle in the shape of a Buddha's hand citron, Qing dynasty, 7.3 x 4.4 centimeters); 8) Bamboo veneer snuff bottle with prosperity, longevity, and ''ruyi'' symbols (18th century, Qing dynasty, 5.6 x 4.1 centimeters); 9) Jade peach-shaped snuff box with a prosperity-and-longevity design, Qianlong reign, 1735-1796, with a glass-and-sandalwood case, 8.2 x 5.2 x 4.9 centimeters).

Ru-Yi Scepters

Tsai Mei-Fen wrote in the Taiwan Today: “The ru-yi scepter is a handheld, handle-shaped object, the "head" of which is slightly curved like the palm of a hand. Similar objects can be traced as far back as the Warring States period (fifth century B.C.-221 B.C.). By the Six Dynasties period (220-589), the term ru-yi had appeared and this object had become common among Buddhists and the scholar-gentry. The decorations, patterns and designs of the scepters are all related to the ru-yi's function as a symbol of auspiciousness. [Source: Tsai Mei-Fen, Taiwan Today, April 2009. Tsai Mei-fen is a curator at the National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“There are more than 120 ru-yi scepters in the collection of the National Palace Museum, with most made during the Qing dynasty. Among the more splendid scepters in the collection are larger examples with inlays of semiprecious materials such as jade. Because of the auspicious connotations of the term ru-yi, which means "as you wish," the scepters became a valued gift exchanged among members of the Qing court during festivals and celebrations. Despite the Jiaqing Emperor's attempts to curb this trend of giving extravagant gifts, it continued unabated through the end of the Qing dynasty.

“Throughout Chinese history, emperors received tribute objects while conducting diplomacy with neighboring states. Foreign emissaries would offer tribute, often in the form of rare and precious local products of their homeland, to the court. In return, the court would present a gift in the form of a precious domestically made product. This exchange of gifts between states often involved objects of great value as a means of currying favor and reward.

“The Qing dynasty court, for instance, presented gifts including refined craftworks such as ru-yi scepters, enamelware, porcelain, embroidered pouches and Song-hua ink stones. The rare and exotic objects that foreign states offered to the Qing court included crystal balls, ostrich eggs, telescopes, mechanical timepieces, Western enamelware and Japanese lacquerware, all of which were arranged for display in the court's various palaces.

“These objects were not only appreciated, they also stimulated the exchange of artistic styles and techniques between East and West. For example, Chinese gold painted lacquerware was influenced by the maki-e form of lacquerware from Japan. Furthermore, the Qing court's interest in enamelware and glassware objects was stimulated in part by Western tribute objects. Likewise, in the 17th and 18th centuries, chinoiserie became increasingly popular in Europe as a result of exchange with China.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, University of Washington; Palace Museum, Taipei, CNTO (China National Tourist Office), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei; Shanghai Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021