CHINESE LACQUERWARE

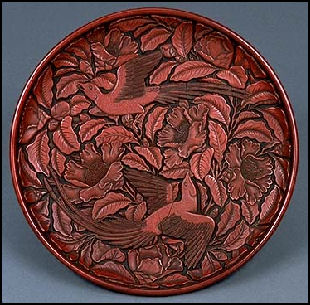

Carved cinnabar

lacquerware plate Lacquerware refers to objects, usually boxes, covered with lacquer (a processed tree sap). In Imperial times lacquerware was greatly prized partly because the large amount of skilled labor required to make lacquer objects. As many as 200 thin layers of lacquer were applied to some objects, with each coat requiring drying and polishing before the next layer was applied.

True lacquer is the sap or resin from the “son” (“urushi”, “thitsi” or varnish) tree, which grows abundantly in China. It has a peculiar buttery smell in its paste form, and produces an intense allergic reaction in many people. It is not unusual for the hands of sufferers to swell to twice their normal size. Even though craftsmen who work with lacquer are not allergic to it they are careful to keep their hands covered.

James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ East Asian lacquer is a resin made from the highly toxic sap of the Rhus verniciflua tree, which is native to the area and a close relative of poison ivy. In essence, lacquer is a natural plastic; it is remarkably resistant to water, acid, and, to a certain extent, heat. Raw lacquer is collected annually by extracting the viscous sap through notches cut into the trees. It is gently heated to remove excess moisture and impurities. Purified lacquer can then be applied to the surface of nearly any object or be built up into a pile. Once coated with a thin layer of lacquer, the object is placed in a warm, humid, draft-free cabinet to dry. As high-quality lacquer may require thirty or more coats, its production is time-consuming and extremely costly.” [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Lacquer is one of the strongest adhesives found in the natural world. It is resistant to water, acids, alkali and abrasion. Lacquer saps comes out of the tree creamy white like latex from a rubber tree and have traditionally been made brown or black by mixing them with resin in an iron container for 40 hours. Around 10 coats of lacquer are applied to a typical piece.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE CRAFTS: BAMBOO CUPS, SEED CARVING AND PAPER CUTS factsanddetails.com ; TREASURES OF THE CHINESE EMPEROR: IVORY CARVINGS, RHINOCEROS HORN CUPS AND CURIO CABINETS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE FURNITURE: TYPES, FUNCTIONS AND QUALITY MING AND QING PIECES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE EMBROIDERY AND TAPESTRIES factsanddetails.com ; TANG HORSES AND TANG ERA SCULPTURE AND CERAMICS factsanddetails.com CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; ART FROM CHINA'S GREAT DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE GARDENS factsanddetails.com QING DYNASTY ART, CULTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts /mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net; Crafts : Kites travelchinaguide.com ; Furniture chinatownconnection.com ; Furniture chinese-furniture.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ancient Chinese Lacquerware” by Qingjun Pan Amazon.com “Chinese Lacquerware” by Guo Xiaoying Amazon.com; “Masterpieces of Chinese Miniature Crafts in the National Palace Museum” Amazon.com “Chinese Art Treasures; a Selected Group of Objects From the Chinese National Palace Museum and the Chinese National Central Museum, Taichung, Taiwan by Guo Li Zhong Yang Bo Wu Yuan, Guo Li Gu Gong Bo Wu Yuan, et al. Amazon.com; “Treasures From the Shanghai Museum 6,000 Years of Chinese Art” by Shanghai Museum Amazon.com “Chinese Objects of Art” by American Art Association and Anderson Ga American Art Association Amazon.com; “Chinese Art and Design: Art Objects in Ritual and Daily Life” by Rose Kerr Amazon.com “Elegant Life of The Chinese Literati: From the Chinese Classic, 'Treatise on Superfluous Things', Finding Harmony and Joy in Everyday Objects” by Zhenheng Wen, Tony Blishen, et al. Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

History of Lacquerware in China

Before 300 B.C., varnishes, enamels and lacquers were made from gum arabic, egg white, gelatin and beeswax. Today most lacquers are made through chemical processes. James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: While items covered with lacquer have been found in China dating to the Neolithic period, lacquerware with elaborate decoration requiring labor-intensive manufacturing processes made its first appearance during the Warring States period. [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Lacquer as an art form developed in China along two distinct paths—pictorial (or surface) decoration and carving of the lacquer. Rarely are the two techniques used in combination. In early times, surface decoration took the form of painting or inlay. The earliest lacquered objects were colored black or red with the addition of charcoal or cinnabar to the refined sap. Because lacquer is such a volatile substance, only a few additional coloring agents will combine with it. During the Han period, incised decoration was also used. Several techniques gradually evolved after the tenth century: engraved gold (qiangjin), filled-in (diaotian or tianqi), and carved lacquer (diaoqi). The art of inlaying lacquer with mother-of-pearl was intensively developed during the Song period. In the sixteenth century, after a lapse of about a thousand years, the painting of lacquer was revived, but it was seldom employed on carved lacquer.” \^/

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: Lacquer, like silk, is one of the products longest known in China. It comes from the sap of a tree which is native to China. It is used by the Chinese to paint decorative designs on wooden boxes and other objects, or is applied in layers so thick as to allow itself to be carved into designs. Baskets painted with lacquer have been recovered from Chinese tombs dating from the first century A.D., and it is probable that Chinese lacquer goes back long before this time. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu]

Lacquerware was introduced to Europe from China. “Lacquer was among the flood of Chinese things that entered Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, where it enjoyed a popularity surpassed only by that of porcelain. Soon an imitative lacquer industry sprang up in France. There by 1730 lacquered cabinets, chests, and other pieces of furniture were being turned out which could bear comparison with the products of China itself. As in the case of early European porcelain, this lacquer work usually imitated Chinese designs very closely. The newborn industry, however, later declined, leaving China and Japan as the primary suppliers of the world's lacquer-ware today.

Lacquer Objects from 2,400-Year-Old Marquis Ti’s Tomb,

On the lacquer objects bronzes dated to 430 B.C. found in Marquis Ti’s Tomb, Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Lacquer, which is highly toxic in the raw, is extracted from the sap of the lac tree indigenous to China. The process of lacquering wood and other materials was invented in China and used to waterproof bamboo and wooden objects as early as Neolithic times, though few pieces survive before the Warring States period. Lacquerware was considered a wonderful luxury because of the hazardous and laborious process involved in making such objects. Highly skilled craftsmen had to apply many thin layers of lacquer to achieve the final effect of a glossy coating. Although we cannot be sure of the cost of the lacquer items in Marquis Yi's tomb, a later text from the first century B.C. reports that the price of lacquer was ten times that of bronze. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

The lacquered outer coffin is 3.2 meters long, 1.2 meters wide and 2.19 meters high. The lacquered inner coffin is 2.49 meters long, 1.27 meters wide and 1.32 meters high. Various creatures are depicted on the coffins. In the Chu culture a large number of spiritual powers both benign and malevolent were venerated and feared. These beings were not understood as ancestors, though they do have the power to interfere in human affairs. In representations they frequently take animal and semi-human form. Scholars are not sure of the role of these creatures played.

The cover of a lacquer trunk decorated with 28 lunar mansions (divisions of the sky). A dragon is represented on one end of the lid, a tiger on the other. This is the earliest known celestial map in China. A lacquer stag (height: 86.8 centimeters, length: 50 centimeters) was found in the marquis' burial chamber. The movable head is fixed with real deer antlers. The body is decorated with small almond shaped designs and tiny dots to resemble the coat of a deer. An unusual lacquer box-cover (length: 82.7 centimeters, height: 44.8 centimeters) is shaped like a duck. The duck has a removable lid on its back and the head can be turned from side to side. It was found in the western chamber, which contained the remains of 13 young women. There were fewer objects in this chamber than the others, but this box stands out for its high level of craftsmanship. The surface is lacquered in black and decorated with red and yellow painting. There is also a lacquer mandarin duck (height: 16.3 centimeters, length: 20.4 centimeters).

Lacquerware Traditions in China, Japan and Korea

James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Carved lacquer is a uniquely Chinese achievement in lacquer art and is also, in a way, lacquer art in its purest form. It is not known when this technique was invented. Lacquers of a thickness sufficient for relief carving were produced no later than the Southern Song period, as is known from archaeological excavations and from materials that were brought to Japan at the end of the Song period. This method of lacquer production reached its greatest flourishing from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century.” [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“In Japan, on the other hand, the underlying shape of a lacquer object is never lost sight of and surface decoration is paramount. The earliest lacquer surface decoration known in Japan, apart from simple designs painted on lacquered objects of the prehistoric period, is the gold and silver foil inlay of the Nara period. Almost certainly this technique was transmitted from Tang China, the source of the dominant cultural influence on Japan at this time. However, once this technique of lacquer decoration had been introduced into Japan, it took on a life of its own and, in fact, continued to develop there into recent times. (Meanwhile, the same technique all but died out in China after the demise of the Tang dynasty in the tenth century.) During later periods, other metals were also used for inlay in Japan, such as lead, tin, and pewter. A technique developed to the highest degree in Japan is the use of gold and silver in powder form, either mixed in to form gold or silver lacquer, or sprinkled over the lacquer surface to create a graduated gold or silver effect. Indeed, the Japanese exploited every physical property of lacquer: as a liquid for painting; as a solid surface that can be built up in certain areas of the composition; and as an adhesive, especially for gold and silver (in either foil or powder form). The resultant works often display great subtlety and delicacy, and maki-e (gold or silver) lacquer is one of the supreme achievements of Japanese decorative art.\^/

“In Korea, too, it is known that lacquer surfaces were decorated with metal foil inlay more or less contemporaneously with the Tang dynasty in China, during Korea's Unified Silla period. In the subsequent Goryeo period, however, perhaps following the lead of southern China under the Song dynasty, mother-of-pearl inlay became the dominant decorative technique for Korean lacquer, and it has continued as such to the present day. Although lacquers of the Goryeo period exhibit some marked similarities to a certain class of mother-of-pearl inlaid lacquer produced in Song China, gradually Korean lacquer evolved a distinctive national style. The finest lacquerware of the late Goryeo and early Joseon periods makes rich use of mother-of-pearl inlay, often in combination with tortoiseshell, and gives an impression of great sumptuousness.\^/

Producing Lacquerware

High-quality lacquerware pieces take a long time to make because many layers of lacquer are applied and each takes a long time to dry. When the process is finished the lacquer is polished to a brilliant shine.

High-quality lacquerware pieces take a long time to make because many layers of lacquer are applied and each takes a long time to dry. When the process is finished the lacquer is polished to a brilliant shine.

Once lacquer becomes hard it is inert and extraordinarily durable. Contrary to what you might think, lacquer dries best in a humid atmosphere. Some craftsmen place their objects for several days after each lacquer application in special closets with the temperature set at 23̊C and the humidity is 80 percent.

The most common colors of lacquer are amber, brown, black and red. Additives can used to make violet, blue, yellow and even white lacquer. Green and violet shades can be achieved with reeki pigments developed in Japan in the early 20th century.

Over time laquer cracks largely because of fluctuations in humidity and the gold and metal foil used as decoration peels away. Restoration involves painstaking cleaning, taking microscopic samples to see what material is best for strengthening the lacquer surface; applying lacquer from the urushi tree or a synthetic resin

Lacquerware Craftsmanship and Design

Lacquerware is usually made by coating split bamboo or wood with lacquer, then adding intricate hand-painted designs or inlays of gold or silver foil or other materials. Typical lacquerware is gold on black lacquer or yellow and green on a red brown background. Master craftsmen carve designs into the layers of lacquer without touching the wooden substrate. Foil has traditionally been kept in place with animal glue.

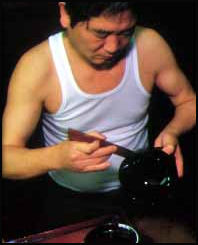

Describing a lacquerware craftsman, W.E. Garret, wrote in National Geographic, an artisan "first weaves a cylindrical frame of bamboo and horsehair, over which successive coats of sap from the thitsi tree are applied. After each layer has dried, a worker puts the cylinder on a lathe for polishing. Using a stick in his right to spin the lathe, he smooths the surface with pumice.

"An artist then creates a pattern by scratching a design and covering the container with pigmented lacquer. Another polishing removes all the color except that caught in the depressions. These steps are repeated with successive colors until a multi-hued design is complete. Some tell a love story; others include figures from astrology or folklore." [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, March 1971.]

East Asian Lacquer Decoration Techniques

East Asian Lacquer Decoration Techniques: 1) Carved lacquer (diaoqi) is a method of decoration involves carving built-up layers of thinly applied coats of lacquer into a three-dimensional design. 2) "Engraved gold" (qiangjin) is decorative technique in which an adhesive of lacquer is applied to fine lines incised on the lacquer surface, and gold foil or powdered gold is pressed into the grooves. [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

3) "filled-in" (diaotian or tianqi) is a decoration in which lacquer is inlaid with lacquer of another color. There are two methods of filled-in decoration: one involves carving the hardened lacquer and inlaying lumps of other colors; the other is called "polish-reveal" (see below). 4) Maki-e is the general term in Japanese for lacquer decoration in which gold or silver powder is sprinkled on still-damp lacquer.\^/

5) Nashiji is a Japanese lacquer technique that produces a reddish, speckled surface, also called "pear-skin," by the sprinkling of especially fine, flat metal flakes over the half-dry lacquer base. 6) "Polish-reveal" (moxian) is a variety of "filled-in" lacquer decoration. Thick lacquer is applied repeatedly in certain areas to build up a design; then the ground is filled with lacquer of a different color and the entire surface is polished down to reveal the color variations.\^/

Carved Lacquerware as a Chinese Art Form

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The rich yet subtle color and the mild touch of lacquerware differ from the cool, dazzling beauty of porcelain or gold and silver. Not only light, lacquer also has the added features of being moisture-proof and insulating. Traditional lacquerware, its production time consuming and labor intensive, has often been regarded as a luxury item. Lacquer wares were not only made as storage boxes, but also used as ritual vessels, served as diplomatic gifts, and even became artworks treasured through the ages. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Carved lacquerware involves engraving through a thick coating of multiple applications of lacquer to create different patterns and designs. Lacquer color and quality along with layers of expression have followed changes in aesthetics and techniques over the ages. Various forms of carving craftsmanship and pattern combinations have led to the rich abundance seen in Ming and Qing lacquer wares.

“Monochrome lacquerware of the Song Dynasty, with its superior form and delicate lightness, approaches the same level of extraordinary refinement seen in "shadow-blue" porcelains. In the Yuan dynasty, the ju-i cloud patterns on carved lacquer were influenced by gold and silver wares, but its flowing lines of lacquer layers became unique to lacquerware. Flower-and-bird motifs found on carved lacquerware of this period can be traced back to metal wares of the Tang dynasty, but the lively forms carved with precision stand out among the thin layers of lacquer in this art form. Noteworthy example of this are 1) “Eight-lobed dish with peacock-and-peony décor” carved black lacquerware made in the second half of the 14th century in Late Yuan to early Ming dynasty (27.2 centimeters in diameter and 2,8 centimeters high); and 2) “Round box with cloud-and-ju-i décor carved lacquerware made during the Yuan Dynasty in the 14th Century (8.4 centimeters in diameter, and 3.9 centimeters high)

Ming and Qing Lacquerware Decoration

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““On carved floral lacquer boxes from the early Ming dynasty official workshops of the Yung-lo and Hsuan-te reigns, scrolling branch-and-flower forms of decoration — like those found on underglaze blue porcelains — may have been influenced by the Islamic world in West Asia. The lacquer quality and refined carving of this period make these works masterpieces. Starting from the middle Ming, decoration turned increasingly towards the painterly Chinese tradition of single-stem flowers, the manner of plum blossom patterns in the late Ming being especially elegant. By the Qing dynasty, these gave way to less naturalistic patterns of crackle and floating plum blossoms that still present a unique sense of cultivated beauty. An example of this is “Round box with peony décor” Carved red lacquerware made in the Ming dynasty during the Yung-lo reign (1403-1424) (26.5 centimeters in diameter and 7.8 centimeters high)[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Unlike floral patterns, early Ming landscape and figure designs on carved lacquer reflected existing themes in traditional Chinese decoration. In landscapes, the sky, land, and water are fitted with a continuous regular pattern typical of carved lacquerware. Early Ming pieces often depict figures in a garden on the subject of viewing plum blossoms or releasing cranes. By the middle Ming, more everyday subjects became increasingly common, such as children playing, ladies, and auspicious figures. By the Qing dynasty, literary allusions became the trend in subject matter, as seen in the engraved names on pieces for "Treasure box on searching for poetic inspiration" and "Treasure box on making friends with pine trees," thus demonstrating the refined taste of the Qianlong Emperor. An example of this is “Round box with scene of appreciating plum blossoms: Carved red lacquerware made in the Ming Dynasty during the Hsuan-te reign (1426-1435) (13.8 centimeters in diameter and 15.1 centimeters high.

“The dragon-and-cloud form of decoration symbolized the imperial clan in China. In the late Ming dynasty, lacquerware from the Chia-ching and Wan-li reigns feature cloud-and-dragon designs churning above mountains and seas. Later in the Qianlong reign of the Qing dynasty, dragons are often shown prancing among winding cloud designs. Likewise, auspicious patterns of prosperity and longevity (ch’un-shou) began to appear in the Chia-ching and Wan-li reigns, dealing with the desire for wealth and long life. In terms of the new technique of carved colored lacquerware, carving through layers of lacquer colors brought out dazzling hues and three-dimensional effects. This method was followed in the Qing dynasty with splendor and variety combined with orderly and meticulous carving. Example of this are 1) “Round box with décor of dragons and the Eight Treasures carved polychrome lacquerware made in the Ming Dynasty during the Chia-ching reign (1522-1566) (32 centimeters in diameter and 17.5 centimeters high); and 2) “Four-lobed box with décor of dragons and characters” Filled-in lacquerware made in the Qing Dynasty during the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) (12.5 centimeters in diameter and 7 centimeters high).

Treasured Lacquer Boxes of the Qianlong Reign

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The craft of lacquerware flourished in the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) during the Qing dynasty, when the categories of objects increased to include screens, teapots, alms bowls, and others. Qing carved lacquer wares also tend to feature gorgeous coloring, tougher lacquer, delicate carving, and full patterning. Although polished, the sharp edges of the carving are still plainly evident for a visual aestheticism differing from that of previous periods. The imperial court also developed unique shapes. Whether it is the "treasure box of floral masses" filled with blossoms in petal form or the grand carriage-shaped box set, all are ingeniously designed and fully reflecting the preference for sumptuousness and ingenuity in court taste. Examples include: 1) “Scarlet Gobi Desert Illustration Vase” made during the Qianlong reign (59.9 centimeters long, 16.5 centimeters wide and 63.6 centimeters high); and 2) Scarlet Carriage-Shaped Three-Layered Box made in the Qing Dynasty during the 18th Century: (25.3 centimeters highm 24.1 centimeters deep and 33.8 centimeters wide) [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Craftsmanship in lacquerware became increasingly complex by the middle Qing dynasty. Layers of different hues in carved color lacquerware, archaic dragon motifs, and continuous geometric or character patterns — complemented by dazzling gold painting on black lacquered interiors — all present an impressive display of visual delight. In the late Qing, the technique of "bodiless" lacquerware rose again in Foochow. Thin layers of silk or linen create an exceptionally light and airy effect that maintains the shape while transmitting the essence of the object. Lacquer painting that incorporates powdered gold and silver foil to give lacquerware vivid color also became an exclusive feature of Fujian products. Among the examples are 1) “Hornless Dragon Square Vase made during the 18th~19th Century (35.2 centimeters high, 16.4 centimeters deep and 16.5 centimeters wide; and 2) “Gold Painted Colored Long Rectangular Box made during the 19th Century: (13.8 centimeters high).

“Two-tiered box with figures in landscape” carved polychrome lacquerware was made during the Qianlong reign (1736-1795) It is 10 centimeters high, 10.7 centimeters long and 8.8 centimeters wide. An Inscription on the base reads” Made in Qianlong.” “The box is divided into base, interior box, and cover sections, which the Qing imperial family had originally used to hold 16 pieces of jade thumb protectors. The shape of the box had been designed with the shape of four thumb protectors in mind. The interior of the box contains two layers, with a hexagonal flower-shaped turtle pattern ground, while the upper and lower edges are decorated with wide borders. The interior is painted in black lacquer. The 4-footed base is painted in red lacquer with floral scroll as decorative border, and a continuous “double square” pattern spreads over the surface of the base. The sides of the feet are in lotus branch pattern, while the bottom surface of the base is painted in black lacquer. The cover is divided into four sections by floral scroll, and sketched with scenes of viewing the lotus, admiring the chrysanthemum and visiting the plum blossoms respectively; the surface of the cover is painted with the Eight Gods and Gods of Longevity circling the mountains and clouds. The thick layers of lacquer are from top to bottom green, yellow and red respectively; the skilful and sharp engraving demonstrates the great experience of the craftman.

Chinese Enamel and Cloisonné

Cloisonne figures Enamel is plastic-like material made from heating together substances such as feldspar, quartz, flurospar, borax, boric acid, soda, potash, saltpeter, clays, ammonium carbonate, stannic acid and water. Colors are produced by adding chemicals such as cobalt oxide for blue. Enameling means coating a base of metal, pottery or other mineral substance with finely powered glass and then heating it until the particles melt together and form a glaze. Chinese enameling is usually done on ceramics. Many times the object is repeatedly dipped in the enameling material before it is fired in a kiln.

To make enamel, ingredients are mixed and melted into a liquid glassy mass and then poured into cold water. The water causes them to shatter into millions of small fragments called frit. The frit is then ground with clay, water and coloring material into a creamy material called slip. Articles to be enameled are dipped into the slip. After they are allowed to dry they may be stenciled or colored using other means. Afterwards they are fired in kilns.

The Chinese also practiced cloisonne, a form of enamel work where colored areas are separated by fine metal bands. Cloisonne glazed in a kiln like porcelain is stronger than porcelain because of the metal framework. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Foreign influence contributed to the development of cloisonné during the early fourteenth to fifteenth century in China. The earliest securely dated Chinese cloisonné is from the reign of the Ming Xuande emperor (1426–35). However, cloisonné is recorded during the previous Yuan dynasty, and it has been suggested that the technique was introduced to China at that time via the western province of Yunnan, which, under Mongol rule, received an influx of Islamic people. A very few cloisonné objects have been dated on stylistic grounds to the Yongle reign (1403–24) of the early Ming dynasty. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Cloisonné is the technique of creating designs on metal vessels with colored-glass paste placed within enclosures made of copper or bronze wires, which have been bent or hammered into the desired pattern. Known as cloisons (French for "partitions"), the enclosures generally are either pasted or soldered onto the metal body. The glass paste, or enamel, is colored with metallic oxide and painted into the contained areas of the design. The vessel is usually fired at a relatively low temperature, about 800̊C. Enamels commonly shrink after firing, and the process is repeated several times to fill in the designs. Once this process is complete, the surface of the vessel is rubbed until the edges of the cloisons are visible. They are then gilded, often on the edges, in the interior, and on the base.\^/

Cloisonné objects were intended primarily for the furnishing of temples and palaces, because their flamboyant splendor was considered appropriate to the function of these structures but not well suited to a more restrained atmosphere, such as that of a scholar's home. This opinion was expressed by Cao Zhao (or Cao Mingzhong) in 1388 in his influential Gegu Yaolun (Guide to the Study of Antiquities), in which cloisonné was dismissed as being suitable only for lady's chambers. However, by the period of Emperor Xuande, this ware came to be greatly prized at court.\^/

Image Sources: 1) University of Washington; 2, 9) Palace Museum, Taipei; 3, 10) CNTO; 4, 5) Kyoto Museum ; 6) Metropolitan Museum of Art; 7, 8) Kent State University

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021