CHINESE GARDENING

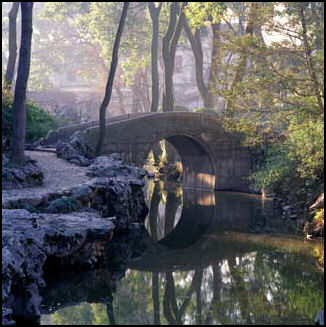

Suzhou garden

Chinese gardens feature plant-lined dirt paths that never seem to follow a straight line, rocks that have special significance and a layout plan that harmonizes with the natural surroundings that sometimes includes natural features many kilometers from the garden. There are few flowers. The principal elements are rocks and water. Chinese gardens often feature "mountain" scenes and complicated architectural tricks such as dead ends and unexpected destinations. The aim often is to create an illusion of natural scenes or miniature worlds. Many principals and concepts of Japanese gardening originated in China. Some of the most beautiful gardens in China are found in Suzhou near Shanghai and Fuzhou in Fujian Province. Tai Lake near Fuzhou is the source of China's most sought after garden stones. They are often used to symbolize mountains.

Chinese gardens are designed to respond to all the seasons and be a microcosm of nature. "Mountains, oceans, islands, and waterfalls are all there in a small horizontal compass," wrote Boorstin. "Rocks, a prominent foil to the fragility of growing trees and shrubs and mosses, affirm the unchanging. They are not the architects's effort to defy the forces of time and nature, but another way of acquiescing. The...garden renews what dies or goes dormant, and reveres what survives." [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Garden design was an art in China. One of the most common ways to make a Chinese home more elegant was to develop one or more compounds into a garden with plants, rocks, and garden buildings. Gardens were especially appreciated for their great beauty and naturalness. In time, garden design came to be regarded as a refined activity for the well-heeled and well-educated. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

“It may be useful to note that what we are calling a garden in China is somewhat different from its counterpart in western Europe or the United States. It is not an expanse of green with incidental buildings, but rather an area in which buildings surround arrangements of rocks, plants and water; without these buildings, the Chinese garden is not a garden. The architectural elements themselves are decorative and structure how one views the scenery. Good views are many and intimate in scale, in contrast with the sweeping vistas and mathematically ordered plantings of European gardens of the same period. The enclosure of the entire compound by walls or other natural barriers marks this area off as a special precinct for private enjoyment.

Except for those emulating a Western lifestyle, Chinese don’t really have yards in the American sense and the idea of custom yard signs is still very novel. Ones that express political views other than deep affection for the Communist Party can result in a prison sentence.

Websites on Gardens University of Washington washington.edu ; China Planner chinaplanner.com ; Garden Photos flora.huh.harvard.edu Suzhou Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Suzhou's Gardens: China.org China.org ; ; UNESCO World Heritage Site site : UNESCO ; Books “The Chinese Garden” by Maggie Keswick (St. Martin's Press); "A Chinese Garden Court: The Astor Court at The Metropolitan Museum of Art" (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Splendid Chinese Garden: Origins, Aesthetics and Architecture” by Jie Hu Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Gardens: People, Activities, Culture” by Hardie Alison Amazon.com; “The Chinese Garden: History, Art and Architecture” by Maggie Keswick , Alison Hardie, et al. Amazon.com; “The Gardens of Suzhou” by Ron Henderson Amazon.com; “Chinese Classical Gardens of Suzhou” by Tun-Chen Liu and Joseph C. Wang Amazon.com

History of Chinese Gardening

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: ““Gardens can be traced back to ancient times in China, but always included the same basic elements. After the Han dynasty, Daoist ideals of disengaging from worldly concerns gave a rationale for gardens as environments in which an individual could escape the often harsh demands of a politically engaged civic life. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

“Gardens were originally simple retreats for contemplation set in nature. Early exponents of the ideal of retreat from public life, like the legendary Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove of the Six Dynasties period, merely sought their own retreat in a ready-made natural setting such as a wooded area or mountain stream. From the Han dynasty onward, some individuals built more elaborate precincts that were based on the models of the imperial grounds. One aristocrat lost his life for assuming for himself this royal privilege, flaunting his wealth with a collection of natural specimens similar to those previously found only in the emperor's Hunting Park.

“Daoist immortals were believed to inhabit remote mountain peaks and practice secret methods of elixir-making there. Portraits of other religious figures, like the Buddhist lohan at the left, were often situated in a landscape with magical qualities. The deer in this painting is a symbol of the Buddha because it is believed a deer was one of his early incarnations. Certain plants and animals were favored for gardens because of their associations with overcoming the limits of ordinary life. Some trees or plants, for example, grew against harsh odds, such as difficult terrain, and certain animals, such as cranes, seemed to possess an ability to survive in ways beyond human capability.

“The emperor, as guardian of the realm, sought to demonstrate a harmonious relationship with and an intimate knowledge of the forces of nature. The imperial parks were vast in territory and kept an abundance of all imaginable plants and animals, almost like a museum. Such parks replicated the emperor's realm in miniature, with man-made lakes and mountains often corresponding to real geographical features. They reinforced the emperor's role as the Son of Heaven.

“By the Tang dynasty, a tradition of painting the royal hunting parks as paradise landscapes had developed. This gradually came to be applied to representations of landscapes in general. Sometime during the Tang dynasty, miniature landscapes in trays (or penjing), composed of rocks, plants and water, began to take the place of the censers (see above). These small-scale landscapes still retained their otherworldly associations. Especially favored were highly contorted rock and plant specimens. Scholars often kept these dwarfed landscapes on their desks, and one Tang dynasty court magician was said to have cultivated the ability to disappear into his tray landscape at will. Collecting unusual rock and plant specimens became common literati pastimes from the Song Dynasty onward.

“The selection of plants for the garden also carried meaning. Private garden builders at first followed the examples of the emperor in collecting exotic plant and animal life in a complete miniaturized version, or microcosm of the realm. In the Song Dynasty, however, many scholars took up garden planning as a cultivated pursuit, writing handbooks on growing a wide number of flower varieties and the collecting and appreciation of unique and valuable rock specimens. There were many private retreats in the estates of scholars in and around the larger cities of Kaifeng, Hangzhou, and Luoyang.

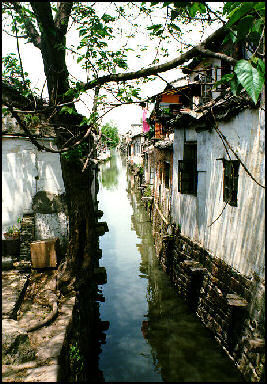

“Garden construction reached a peak during the Ming and Qing dynasties, as landholding aristocratic and scholar elite families moved their main residences from the countryside to urban and suburban areas of southern cities. Suzhou in particular became a place of refined culture, renowned for its canals and mild climate, as well as the ready availability of garden building expertise.

Development of Gardening in the Suzhou Area

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Gardens were an important part of the homes of the elite long before Ming times, but reached their fullest development in the late Ming in the Jiangnan area, which comprised the southeastern part of China south of the Yangtze River, including the densely-populated cultural centers of Yangzhou, Hangzhou, and Suzhou. These gardens served multiple purposes for their owners. They were extensions and developments of a family's property; they added cultural value by providing a pleasurable environment for private relaxation and entertaining friends and colleagues. In some cases they also contained a productive agricultural portion in the form of orchards or fields for cash crops that could support the needs of a large extended family. But most gardens were luxury items that demonstrated and enhanced the status of their owners. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“The movement of wealthy families of elite status to the Jiangnan region, which began during the Song dynasty and continued into the Ming, had an impact on the popularity of private gardens. Jiangnan was an area where things grew easily, aided by mild winters with plenty of rainfall. As these wealthy families shifted to urban areas, they established urban estates as their primary residences. Members of the literati and merchant classes who had the means and ambition to do so created intimate urban gardens within their household compounds as microcosmic replicas of nature.

"The gardens of Yangzhou and Suzhou in particular became famous. Tradesmen in turn responded to the demand, and these cities became centers for garden design, construction, and the distribution of the basic materials required to build a garden, such as flowering plants and shrubs and garden rocks. “Building a garden gave a person the opportunity to demonstrate his knowledge and cultivated taste. Even the most experienced and talented carpenter was not presumed to understand the philosophical principles needed to create a coherent design.

Types of Chinese Gardens

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “According to historical records of the Zhou dynasty, the earliest gardens in China were vast parks built by the aristocracy for pleasure and hunting. Han-dynasty texts mention a greater interest in the ownership of rare plants and animals, as well as an association between fantastic rocks and the mythical mountain paradises of immortals. Elaborate gardens continued to be built by members of the upper classes throughout China's history. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“A smaller, more intimate type of garden is associated with scholar-gentlemen, or literati, and have been celebrated in Chinese literature since the fourth century A.D. Paintings, poems, and historical books described famous gardens of the literati, which were often considered a reflection of their owners' cultivation and aesthetic taste. The number of private gardens, especially in the region around Suzhou in southern China, grew steadily after the twelfth century. The temperate climate and the great agricultural and commercial wealth of the region encouraged members of the upper class to lavish their resources on the cultivation of gardens. During the period of the Mongol conquest in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, many literati in this region found official employment either disagreeable or hard to obtain and therefore devoted themselves to self-cultivation and the arts. The garden became the focus of an alternative lifestyle that celebrated quiet contemplation and literary pursuits, often in the company of like-minded friends.\^/

Chinese Garden Design, Elements and Feng Shui

Suzhou canals

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: The garden "designer, ideally the patron himself, had to master such diverse fields as siting (fengshui), architecture, water management, botany, and landscape design, as well as be familiar with the poetic and painted gardens and parks of the past. One of the most characteristic and outstanding features of the Chinese garden is the artificial mountain built of individual stones, which were cemented together to form complex structures.These were often placed carefully in the garden compound as focal points of a larger view, or as ideal vantage points themselves. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Traditional Chinese gardens were meant to evoke a feeling of being in the larger natural world, so that the occupant could capture the sensations of wandering through the landscape. Compositions of garden rocks were viewed as mountain ranges and towering peaks; miniature trees and bushes suggested ancient trees and forests; and small ponds or springs represented mighty rivers and oceans. In other words, the garden presented the larger world of nature in microcosm. Masses of colorful cultivated blossoms, flowerbeds of regular geometric shape, and singular vistas (such as the formal gardens at Versailles) were all avoided, in keeping with the goal of re-creating actual landscapes. Instead, the many aspects of a Chinese garden are revealed one at a time. A garden's scenery is constantly altered by the shifting effects of light and the seasons, which form an important part of one's experience of a garden and help engage all the senses, not just sight. One of the most important considerations in garden design is the harmonious arrangement of elements expressing different aspects of yin and yang. The juxtaposition and blending of opposites can be seen in the placement of irregularly shaped rocks next to smooth, rectangular clay tiles; soft moss growing on rough rocks; flowing water contained by a craggy grotto; and a dark forecourt that precedes entry into a sun-drenched central courtyard. [Source: Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Fengshui (or wind-and-water, or geomancy) also played a large role in the form a garden would take. The natural environment was interpreted by the fengshui master as a living organism, the alteration of which could positively or negatively affect the lives of people in contact with it for generations to come. The lore of mountains and rocks, important in Chinese religion and art, was also an indispensable part of garden landscape design. Large rocks placed by themselves or groupings of smaller rocks served as analogies for mountains, which were considered sacred sites and potential resting places for immortals.

The five directions of Chinese cosmology and feng shui are north, south, east, west and center. South represents light and brings good luck. North represents darkness and brings bad luck. Accordingly, doors of houses should not face north of northwest: they should face south. The entire house should be oriented towards the south with mountains to the north to block the bad luck from entering and keep good luck from escaping. The best location is at the foot of a mountain, facing a river. Waters helps attract qi. Buildings with a square plan help hold it firmly.

See Separate Articles: FENG SHUI: HISTORY, BUILDINGS, GRAVES, HOMES, BUSINESS AND LOVE factsanddetails.com ; IMPORTANT CONCEPTS IN FENG SHUI factsanddetails.com ; FENG SHUI, QI AND ZANGSHU (THE BOOK OF BURIAL) factsanddetails.com

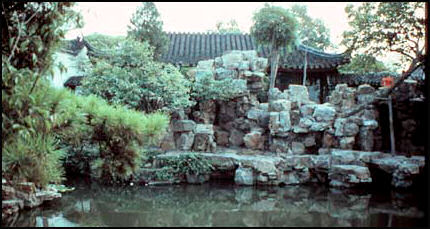

Rocks in Chinese Gardens

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Rocks have long been admired in China as an essential feature in gardens. By the early Song dynasty, small ornamental rocks were also collected as accoutrements of the scholar's study, and the portrayal of individual rocks, often joined with an old tree or bamboo, became a favorite and enduring pictorial genre. By the fourteenth century, depictions of gardens almost always included representations of a fantastic rock or "artificial mountain" and scholars' rocks often supplanted actual scenery as sources of inspiration for images of landscapes. Sculptural garden rocks, with distinctive shapes, textures, and colors, have always been treasured as focal points of Chinese gardens. By the Tang dynasty, three principal aesthetic criteria had been identified for judging both garden stones and the smaller "scholars' rocks" displayed in literati studios: leanness (shou), perforations (tou), and surface texture (zhou). These criteria led to a preference for stones that were vertically oriented, often with a top-heavy shape; riddled with cavities and holes; and richly textured with furrows, dimples, or striations.”\^/ metmuseum.org \^/]

According to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Although Chinese garden design changed considerably throughout the centuries, the uniquely perforated limestone rocks from Lake Tai near Suzhou have been admired, collected and featured in private gardens since the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The centerpieces of many literati gardens, large T'aihu rocks in combination with other stones, represented the great mountains of the universe. By the 17th century, Suzhou gardens were in effect, symbolic metaphors for the forces of the universe and the balance found in nature. [Source: Minneapolis Institute of Arts |:|]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Rocks were to the Chinese garden what sculpture was to its European counterpart. A deep appreciation for rocks stemmed from ancient religious attitudes toward nature, which included the veneration of mountains. Rocks were believed to have a concentrated amount of natural energy and symbolized the dwelling places of the Daoist immortals. A region with rugged, lofty and remote terrain was believed to produce especially potent minerals and plants that, when consumed in just the right combination, would guarantee longevity if not immortality itself. Rocks were introduced into the garden as individual specimens and as components of complex rockeries. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“As an element, rock is classified by the Chinese as "yang" because it is strong, durable, hard and "male"), but the best garden stones also exhibited spareness and delicacy. Top-heavy, rugged stones that seemed to defy gravity and to hang in the air like clouds were the most highly prized. If a rock appeared porous with many holes penetrating all the way through and had a strangely contorted overall form, it was considered a highly valuable asset to the garden. Lake Tai near Suzhou produced the most prized rocks; the chemical composition of the Great Lake caused the limestone on its bed to erode in an irregular fashion.

“Rocks were placed not only in gardens, but also were treated as art objects, to be put on display inside, perhaps on a scholar's desk. Certain types of rocks, such as the Lingbi rock, shown to the right, were highly appreciated for their luster, unusual shapes, interesting veining, or the cavities that formed within them. Often these rocks were highly polished and placed on custom-made stands. Rocks were also arranged to form the edges of man-made streams and ponds, with great care taken to make small details like this stream appear as they might in nature. Grottoes and caves were believed to share in common with the eroded stones from Lake Tai a heightened source of cosmic energy or qi, due to being formed by the concentrated action of water upon stone deep within the earth. Certain types of stones were collected for the melodious sounds they made when struck. Others, like the one at right, were recognized as "found" art works, completed by nature itself. They are typically displayed within one of a garden's many halls or studies.

Water in a Chinese Garden

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Water is a central component of the Chinese garden. When planning a garden, the first step was to investigate the source and flow of water available at the site. Builders of urban gardens usually began by dredging streams and digging out ponds, because sites were far removed from the natural environment. The excavated earth would then be used to build hills and mountains that gave the garden its particular character. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“Water was believed to serve as a balance for other elements in nature and in the garden. As a visitor walks through a garden, water reflections and contours interact with other components. Bodies of water could catch the eye by glinting in the sunlight, or establish a particular mood reflecting a gray sky.

“The water in a city garden is typically broken into small, separate areas that are sometimes connected with ponds or flowing water. Pools are made to wander, disappear, then reappear at the next corner. The sites generally considered to be the best in the garden are those at the edges of lakes with a view of mountains or hills beyond. Semi-circular bridges are often chosen because they "complete themselves" as they are reflected in the water; they are also a symbolic reference to the moon. One expression equates watching the moon (as reflected in water) with "washing the soul." The water quality was not always clean and brilliant - often the ponds are rather murky and opaque.

Suzhou garden

Buildings in a Chinese Garden

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Despite the fact that many buildings in gardens could actually serve as residences year round, most garden architecture is fanciful and decorative. The overall arrangement of buildings divides the interior space of the garden into smaller cells that contain one or many small scenic views. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“Buildings in a garden are often connected by covered walkways and different spaces are visually linked by views glimpsed through open doorways, lattice windows, and decorative openings in walls. At other times, the view is purposely obstructed by building placement and other "natural" barriers such as artificial mountain structures. A garden's planner would also consider how a particular view might change as a visitor walked.

“Chinese garden designers use "borrowed views," picturesque views that are framed by parts of the buildings themselves but exist beyond the walls of the garden proper. Sometimes views are borrowed from other parts of the garden. "Leak windows" are openings decorated with lattice designs that allow the viewer glimpses into smaller courtyards and spaces that the building would otherwise hide.

Plants in a Chinese Garden

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Chinese garden designers followed a fairly traditional approach in the choice of plant materials. They selected and cultivated long-standing favorites that carried symbolic meaning in poetry and literature, like the pine, cypress, plum and bamboo, as well as flowering plants like the peony, orchid, and chrysanthemum. Some of these plants were associated with famous historical figures, while others were especially cultivated in certain areas. The peony, for example, was linked closely to Loyang because it was cultivated there with great skill. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

Chinese bonsai (called "pending") are larger than their Japanese counterparts. The art form dates back to A.D. 200 and was deeply influenced by the form of Chinese Buddhism that begat Zen Buddhism. Between the eighteenth and early twentieth centuries, a wide array of botanical items was introduced into western Europe from China. As these new materials became available and design ideas borrowed from China gained greater acceptance, European gardens of the period acquired a new vitality and emphasis on exotic naturalism. Despite the great variety of plant life available at home throughout China, the garden patron still relied heavily on traditional plant selections to create a symbolic environment.

“Many of the plants selected for display in the garden had a rich history of literary associations. In ancient works like The Book of Odes, it is evident that plant symbolism was already well developed in the Zhou dynasty. For example, because pines were tough and rugged, they were considered symbols of the virtuous scholar who weathered the political ups and downs of official life; the cypress, twisted and withered, was a symbol of longevity. Bamboo was considered the emblem of the perfect Confucian gentleman, who kept his virtue pure and his emotions in check; like a bamboo stalk, he kept his inner self empty and untroubled, and could bend in the wind without breaking.

“Often the visual effects of plant materials were more important than the plants themselves: they created dappled lighting effects on otherwise plain walls, and when placed in conjunction with water features helped to visually expand the space of the otherwise cramped urban garden. The plantain has large leaves like that of a banana tree. It was associated with poor scholars, since the leaves were wide enough to write on when paper or silk was scarce. It was also valued for the somewhat melancholic sound raindrops made when hitting its broad leaves.

Social Activity in a Chinese Garden

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “As pleasant retreats that were easily accessible, gardens were favorite locations for social gatherings of many kinds. One could entertain distinguished guests, throw elaborate or intimate parties, or relax in private with family members. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

The gardens of more elegant homes afforded the residents greater total living space and flexibility in entertaining guests. The garden served as an extension of the house proper in summer, and often the architecture built within the garden portion of the family compound included habitable living quarters. These rooms could prove to be more comfortable during the hot summer months, being ideally positioned to take advantage of breezes off the central pond and surrounded by plantings of aromatic flowers and herbs. Some of the wealthier families could extend their hospitality to friends or colleagues in need of temporary lodging, and the guest, especially if he were a painter or poet, might even spend a productive year or two as an extended member of the household, providing the host with paintings, calligraphy, or serving in some literary capacity in lieu of his expenses.

“Because it remained within the walls of the family estate, the garden was also considered an acceptable location for the women of the household to relax, enjoy a pleasant and safe natural setting, and socialize among themselves and with visitors. Many popular stories and novels of the Ming contain family dramas that take place within garden walls. In The Story of the Stone (also known as Dream of the Red Chamber) by Cao Xueqin, for example, most of the young hero's trials and tribulations occur in the gardens of the family estate.

“Gardens were often constructed by members of the scholar class with the intention that they would provide a hospitable location for gatherings devoted to cultivated pursuits like painting, calligraphy, and playing the zither, as well as for discussing important topics of the day. Chinese scholars have often characterized art activities as means to purify their thoughts and quiet their emotions. These pursuits were considered essential for counterbalancing the chaotic realms of social responsibility and political career.

“Since the time of the renowned Six Dynasties calligrapher Wang Xizhi, wine drinking has been viewed as an incentive or encouragement to creativity in the arts. Poetry gatherings were often modeled on Wang Xizhi's famous Orchid Pavilion outing, in which guests were penalized with a cup of wine for not being able to compose an impromptu poem. Literary quality was determined not only by skill with rhymes and diverse subject matter, but also with innovation and spontaneity.

Master of Nets garden

Aesthetics of a Chinese Garden

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Designing a garden was seen as an intellectual pursuit, and often took a lifetime to perfect. The garden was an unfinished work constantly under revision and improvement. In its aesthetic goals and the symbolism employed, it was closely linked to activities such as Chinese painting. To an individual of cultivated tastes, the scholars' gardens of the Ming represented a culmination of many values expressed in other art forms like painting, calligraphy, and poetry. Landscape painting in particular was very influential on garden design. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington]

“The aesthetic goals of a Chinese garden were not the same as those in typical Western gardens. An overall impression of tidiness and precision rarely strikes the visitor to a Chinese garden. Unlike its Japanese counterpart, the Chinese garden is enjoyed for its apparent disorder. Most gardens try to incorporate aspects of rusticity and spontaneity inherent in nature. This is a similar goal to that found in many Chinese paintings where subjects, such as gnarled trees or rigid bamboo (see the painting at the top of this page), are often chosen for their character.

“The personality of the garden's designer determined to a large extent the types of buildings, plants, and other features that were selected. The exterior environment might also influence how rustic or elegant a garden was in its architecture and decorative details. Another preference in garden design is to use shapes that metaphorically refer to elements in nature; some of the subtlest examples of this practice are also the most highly appreciated. The wall opening, above, is one example of an allusion to nature.

Garden Furniture and Plants in the Painting "The Eighteen Scholars"

"The Eighteen Scholars" by an anonymous, Ming dynasty artist is a hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, measuring 173.7 x 102.9 centimeters. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ “Ming literati emphasized beauty in garden life, using potted plants and scenery to embellish the surroundings and add lofty elegance to their residences. The garden vegetation found in "The Eighteen Scholars" includes various types of trees (Buddhist pine, paulownia, locust, Chinese sweet plum), flowers (peony, lily), ornamental foliage plants (palm, calamus, plantain), bamboo (mottled bamboo), and grasses (mimosa)., Cylindrical planter,shallow rectangular blue planter, Purple spittoon-shaped flower “zun” vase, "The Eighteen Scholars" (Zither)

“This cylindrical planter features a base of blue and green glaze, its body divided into three levels of decoration. The top has auspicious floral patterning, the middle winding lotuses, and the bottom hooked "ruyi" motifs. Next to it is a shallow rectangular blue planter with a flat extending rim and a short body supported by four cloud-shaped feet. A purple spittoon-shaped flower "zun" vase in front also sits on a wide, flaring stand, which itself rests on a platform planter. The body is divided into lotus blossom forms supported by "ruyi"-shaped feet., Rectangular planter, "The Eighteen Scholars" (Go)

“Resting on four cloud-shaped feet, this rectangular planter has a shallow body and a flat extending rim with an "S"-shaped divider in the middle. This is a combination wet-dry planter, with one part holding water and the other earth for both calamus and mimosa plants. Placed within the planter is a Jun porcelain bowl in the shape of an inverted bell that rests inside a purple Jun porcelain drum-stud washer basin to hold the water seeping through, thus serving both aesthetic and practical functions., Courtyard Rockeries

“An exotic Lake Tai garden rock appears craggy and archaic sitting within a delicate raised platform planter with a foliated rim. The stand fluted, the rock stands in the middle to add beauty to the scenery. The marble stand in the form of an inverted lotus used for a rockery in an imperial garden is pure white in color, fine-grained, and mellow in appearance., "The Eighteen Scholars" (Calligraphy)

“With roots exposed, the miniature pine tree has a strong and verdant canopy featuring distinct layers in beautiful forms. The old pine is in a rectangular planter with light purple glaze. It has a flat extending rim and straight walls, the bottom supported by four cloud-shaped feet. It is complemented by a pair of potted calamus plants. One is in a Jun porcelain planter shaped like an inverted bell and placed in a three-legged drum-stud Jun porcelain washer. The other is in a spittoon-shaped flower "zun" vase.

Imperial Chinese Books Related to Gardening

“Illustrations of Sui Garden with Poetic Inscriptions” written by Yuan Chi. The measuring has an 1868 Qing dynasty edition. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Yuan Mei, from Ch'ien-Tang, had passed the civil service exams early in his youth. At the age of thirty-nine, he left his government post to return home. Because he greatly loved the elegance of Nanking, he renovated Sui Ho-te's former residence Chih-shan Garden and re-named it Sui Garden. As Yuan Mei was a well-known connoisseur of fine cuisine and eloquent poetry who was active in the literary world, his residence Sui Garden became famous far and wide. Unfortunately, the Sui Garden was destroyed during the T'ai-p'ing Rebellion (1851-1864). Yuan Chi, a descendant of Yuan Mei, created from his memory paintings of Sui Garden, which he compiled into an illustrated album. Moreover, the book includes four chapters of inscriptions written by contemporary officials and scholars who all had been guests of Sui Garden. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Chieh-tzu Garden Painting Primer” was compiled by Shen Hsin-yu. The National Palace Museum, Taipei has an 1679 edition. “Chieh-tzu Garden, located in Nanking, belonged to the eminent writer Li Yu who lived during the late-Ming and early Qing dynasties (1610-1680). During 1679, Lu Yu and his son-in-law, Shen Hsin-yu, began having many enthusiastic discussions about paintings. However, Li Yu was not a talented painter and was unable to paint the beautiful surrounding scenery, which greatly saddened him. To please his father-in-law, Shen hired the famous painter Wang Kai (1654-1750) to paint additional prints to supplement a volume of forty-three landscape album leaf paintings, a family heirloom originally painted by the late Ming dynasty painter Li Liu-fang (1575-1629). The final volume completed by Wang Kai, which Shen presented to Li Yu as a gift, had in total 133 prints. Li Yu greatly loved the gift from his son-in-law. Unlike earlier art connoisseurs who were reluctant to publicly display their art collections, Li Yu wanted to share this great work with others. Consequently, the Chieh-tzu Garden Painting Primer was published for students of painting.

“The Primer was published in four sections. The first section of landscape paintings was published in 1679. The second and third sections were published after Lu Yu's death in approximately 1701. The fourth section, which includes 324 figure paintings by different artists from various areas of China, was finally published in 1818. On display in this exhibition is the Primer's first section.

Suzhou's Gardens

Gardens were laid during the Tang, Yuan and Ming dynasties and restored after the Cultural Revolution when they were destroyed because flowers were deemed reactionary and gardeners were considered capitalist tools. Some of Suzhou's gardens have a reputation for being poorly maintained and full of weeds and Chinese package-tour groups. Some people feel this reputation is undeserved.

The gardens have been built and rebuilt many times and altered to such an extent so they are no longer Yuan or Ming gardens any more. Many are meandering and asymmetrical. The classic gardens all contain pavilions and houses that open to courtyards, ponds, orchards, "mountain" scenes and evil-spirit-tricking features such as dead ends and unexpected destinations.

Flowering plants and trees include osmanthus, canna lilies, salvias, lotus, and peonies. They each bloom in their own season. Peonies, for example, bloom in April. There are also lots of pruned and carefully maintained bamboo, banana and gingko trees. The gardens are famous for their stones, which have been placed in rivers to be sculpted naturally by flowing water and time.

Suzhou gardens include Lingering Garden (1525), the home of a perfectly placed stone called Cloud-Capped peak; Blue Waves Pavilion (12th century), on the banks of a canal; Western Garden, more of a temple than a garden; and the Garden of Pleasure, built in the late 1800s.

The gardens in Suzhou are a UNESCO World Heritage Site. About 15 gardens, most of them located within the roughly one-square mile old city, are open to the public. The gardens are open from 9:00am to 5:00pm. From 6:00am to 8:00am they are sometimes open for free for exercise. Web Sites: China.org China.org ; UNESCO World Heritage Site site UNESCO Book : “The Chinese Garden” by Maggie Keswick (St. Martin's Press).

See Separate Article SUZHOU AND ITS AMAZING GARDENS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1) University of Washington; 2, 9) Palace Museum, Taipei; 3, 10) CNTO; 4, 5) Kyoto Museum ; 6) Metropolitan Museum of Art; 7, 8) Kent State University

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021