JADE AND CHINA

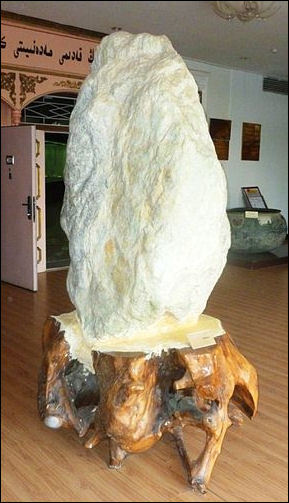

Large mutton fat jade piece

in Hotan Cultural Museum

Jade has long been imbued with mythical properties in China, where it is believed to bring better health and ward off evil spirits. Known as the "Stone of Heaven," it was more valuable than gold or gems in imperial China. According to an ancient Chinese proverb: "You can put a price on gold, but jade is priceless." John Ng, a jade specialist and author of “Jade and You”, told Smithsonian magazine, " The Chinese or Japanese have no hesitation in buying good pieces to give their families or friends for good luck. To the Asian, giving jade conveys a special feeling."

The Chinese word "yu which we translate as "jade" actually refers to any rock that is carved. "Jade" in Chinese usually refers to the minerals nephrite or jadeite but can also, in the broad sense of Chinese tradition, can cover a wide range of the beautiful stones like agate, crystal and turquoise. Some 30 or 40 different kinds of mineral in China are called yu. Nephrite is known as "lao-yu" (“old jade”) or "bai-you" (“white jade”) and jadeite is known as "fei-cui-yu" (“kingfisher jade).

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The process of shaping jade is both time and labor-intensive, leading Confucius (c. 500 B.C.) to compare the process to the cultivation of an educated person. In addition to being a symbol of luxury and wealth, jade is associated with the qualities of purity and refinement and is often believed to possess magical powers. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts-washington-edu/chinaciv /=]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The concept behind the saying, "The virtue of a gentleman should be like that of jade," has its roots in the Neolithic period and matured in the Eastern Zhou, Qin (221-207 B.C.), and Han dynasty (206 B.C.-220 C.E.) periods. In fact, regardless of whether jades served as auspicious objects or decorative pieces to reflect the status of a member of the nobility, or whether jades were admired by the living or used to accompany the deceased, the virtue and beauty of jade had always been associated with the aristocracy in China, forming a unique culture of reverence for jades among the Chinese people. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Pursuing optimal equilibrium and harmony between human and nature has always been a key concept in Chinese aesthetics. When it is embodied in the art of jade carving, fitting the design to the material and its inherent property is the guiding principle. In short, the principle means that the natural hues or forms of the material in use induce the theme and designs of the work to be rendered. The artisan fully contemplates the substance and characteristics of the material at hand, which seems to restrict yet actually challenges him and ultimately inspires his creativity. "

See Separate Articles: JADE: SOURCES, MINERAL COMPOSITION, COLOR AND BUSINESS factsanddetails.com ; EARLY CHINESE JADE CIVILIZATIONS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JADE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; International Colored Gem Association gemstone.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Jade: “Jades from China” by Angus Forsyth Amazon.com; “Jade: A Study in Chinese Archaeology & Religion” by Berthold Laufer Amazon.com “Jade and You” by John Ng Amazon.com ; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “Hongshan Jade: The oldest, most imaginative jades full of mysterious beauty” Kako Crisci Amazon.com ; “Qijia (Jades of the Qijia and related northwestern cultures of early China, ca. 2100-1600 BCE” by Dr. Elizabeth Childs-Johnson and Gu Fang Amazon.com; Ancient Chinese Jade Collection: Chinese Edition. by Henry Liaw and C.F. Zhou Amazon.com ; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com;“Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com

Jade and Ancient China

The Chinese have revered jade since Neolithic times. Jade has had symbolic value in Chinese culture since very early times, and has been found in many eastern Neolithic tombs. Archeological data shows that the ancient Chinese were using nephrite jade to make ornaments and weapons between 7000 and 8000 years ago. According to the Chinese creation myth, after man was created he wandered the earth, helpless and vulnerable to attacks from wild beasts. The storm god took pity on him and forged a rainbow into jade axes and tossed them to the earth for man to discover and protect himself with.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ From the middle Neolithic age to the Han dynasty, a period spanning more than 6,000 years (ca. 6000 B.C. to A.D. 220), the art of jade carving in China developed with the evolving political, economic, and social climate to form a “jade venerating tradition” that attributed a vital force and the power to channel spirits of the other world to this precious mineral. This vast epoch may be called the “classic period” of Chinese jade. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Some scholars have suggested that Chinese civilization was built around jade. According to the Shanghai Museum: China, with its 8000-year history of jade carving, has long enjoyed a reputation for being the ‘Home of Jade’. In ancient China, jade was highly valued not only for its intrinsic beauty but also for its mystical allure. The rulers believed it to be a symbol of wealth and power, and used it as a personal adornment, a sacrificial ritual implement, as well as a funerary object capable of averting evil spirits. The natural properties of jade were thus endowed with personal and moral significance.Chinese jade workmanship had reached a high technical level by pre-historic times in the selection of material, in decoration and design, and in carving and polishing. While ritual jades developed fully during the Xia, Shang and Western Zhou dynasties, ornamental jades in various intricate shapes flourished in the Spring and Autumn, the Warring States and Western Han periods. However, the craft declined in the years between the Eastern Han and Northern and Southern Dynasties. It revived in the Tang and Song dynasties, when jade shed much of its ritual significance. Depictions of nomadic life were a special feature of the jades of the Liao and Jin dynasties, while the crafting of particularly large pieces marked the Qing, by which time the popularity of jade had spread over a much wider segment of society. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Jade Objects in China

Five Rats

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““With respect to function, jades of the Shang and Zhou can be categorized into ritual, ornamental, and funerary objects. “Ritual jades consist of the "pi", "ts'ung", "kuei", "chang" and "ping". Jade weapons include the "ch'i", "fu", "yüeh", and "ko", also including the auspicious flat and pointed "kuei", indicating the status of an aristocrat. That is the reason why the "ko" and "pi" as well as "yüeh" and "pi" have often found in "kuei" and "pi" sets by archaeologists.

“Jade accessories that were commonly worn include the "huang" (strung with different beads) and ladder-shaped (strung with beads, larval forms, and "ko") ornament sets. Occasionally, there are jade ornaments with dragon-and-phoenix, human-face, and various other animal designs. The jade sets that prevailed among the upper levels of society at the time are called "ornaments of virtue" in historical documents, alluding to the high social status and noble position of the wearer. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The jade sets of facial coverings used in burial were the predecessors of funerary pieces of jade clothing used in the Han dynasty. Moreover, jade fish and silkworms were either strung together for funerals or placed in the mouth of the deceased. All these jade objects demonstrate the ancient reverence for the virtue associated with jade by the Chinese.

“In bronze inscriptions, jade is mentioned mainly for rewards, conferring nobility, formal meetings, tributes, and sacrifices. The jades mentioned in inscriptions on the Hsien-chi "kuei", Sung "ting", Shih-sung "kuei", and Mao-kung "ting" bronze vessels reveal that the aristocracy employed a ritual system in which jade and silk played crucial roles and that the virtue of a true gentleman was likened to the resilient purity of jade.

Common Ancient Jade Objects

Dragons made from jade have existed for thousands of years. Starting from the Hongshan culture (30th century B.C.), the form of jade dragon underwent a continuous evolution through thousands of years' history with characters of ages. There are pieces in shape of a dragon or with a design of dragon, symbolizing status, power and good luck. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Bi disc is a flat round piece or disc of jade with a hole in the center. It is one of the representative jade wares that often found in tombs of the Liangzhu culture (31st-22nd century B.C.). It was originally used as a ritual vessel to offer sacrifice to the God of heaven, but gradually lost its ritual function in thousands of years' development. It appeared more decorative later with fine workmanship and beautiful designs.

Cong is a ritual jade. Examples from the Liangzhu culture (31st -22nd century B.C.) consist in a square column shape with a round perforation through the center. It usually has man-like figure and animal mask designs at the four corners and was used to offer sacrifice to the God of earth according to the ancient Chinese philosophy of "round heaven and square earth". It gradually decreased in number after 221 B.C.

Decorative pieces for swords were very popular for the nobles in the period from Eastern Zhou to Han dynasties (770 B.C.- A.D. 220) to decorate their swords with jade pieces to show their dignities. So there appeared jade sword pommel and guard, and scabbard slide and shaped.

Han is a jade piece put in the mouth of the dead upon burial. This burial custom could be traced back to the Neolithic Songze culture (3800-3200 B.C.). In the Han dynasty (206 B.C.- A.D. 220), it was mostly in a cicada shape because people then believed that the dead could regenerate like cicada.

Wo was a pair of jade pieces put in hands of the dead upon burial. In the Han dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220), they usually appeared in a pig shape as pig then was a symbol of wealth and people wish to have wealth accompany them to the next life.

"Spring water" and "Autumn mountains" are jade pieces of the Liao and Jin dynasties (916-1234) with designs describing the northern nomadic mores of hunting in spring and autumn, such as a falcon catching a swan and a group of deer in the forest.

Jade Symbolism in China

Jade tablet, 3200-2000 B.C.

Revered for its hardness and texture, jade symbolizes the cosmos, wealth, political power, security, good health and strength. In China, jade cicadas have been placed on the tongue of the dead to speed resurrection; jade pigs symbolize prosperity, jade disks represent heaven and a piece of jade enclosed within a square signifies the earth. Jade is prescribed as a medicine and credited with having miraculous powers and the ability to ward off evil and bad luck. A villager in Xinjiang told the Los Angeles Times, “I believe it will cure everything. I have heard when it touches your skin, it sucks out the poisons.”

In imperial China jade was considered a bridge between heaven and earth. Confucian scholars compared the 11 virtues of jade as models for human behavior. Confucius himself equated the stone with intelligence, truth, loyalty, justice, purity and humanity, and he used the stone to symbolize the idea of “junzi”, the noble or superior man. Taoist alchemists mixed up elixirs with powdered jade that they hoped would make them immortal.

The emperors communicated with the gods through jade disks; and Chinese poets called the skin of beautiful woman "fragrant jade" and the part of her body which men love so much to enter, her "jade gate." A jade donut has traditionally been given as a gift to newborns. Jade gifts were commonly given as bribes to corrupt Chinese officials. In athletic events second and third place contestants were given trophies of gold and ivory, while the winners were awarded jade.

Cultural implications of ancient Chinese jades according to the Shanghai Museum: 1) A symbol of wealth and power. Many archaeological excavations have proved that most of the jade wares were owned by the upper class in ancient China. Large quantities of finely worked jades buried in the tombs of clan leaders and royal family members reflected their luxuriant wealth and special power. Along with the establishment of social rites in the Western Zhou dynasty (11th century-771 B.C.), a system of using jade was brought into being. The type, size, design, color and quality of the jade wares became a status symbol of the wearer. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

2) An envoy of religious deities: The ancient Chinese believed that jade could be a kind of link between human beings and gods and had a special function to get rid of evils. So it had been used in sacrificial ceremonies to worship the gods of nature and commemorate ancestors for blessing, or worn as an amulet and ornaments, or buried for the dead.. 3) A mark of morality The ancient Chinese had related the natural qualities of jade with human morality, as Confucius claimed that jade had the qualities of benevolence, wisdom, justice, courtesy, loyalty, happiness, trustworthiness, heaven, earth, virtue and truth. So, wearing jades became very popular among the Chinese. People of all classes liked to wear jades to show their identity, and at the same time standardized their own behavior.

Jade, Spirituality, Immortality and Rituals in China

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “With a glistening sheen just like the springtime sunshine, believed to be high in jinqi (vital force or energy), this beautiful jade was fashioned after the concept of yin and yang into round bi discs and square cong tubes, and marked with deistic and ancestral images as well as "encoded" symbols. A power of "affinity" born of "artifacts imitating nature", so they hoped, would enable dialogues with the Supreme God, who imparted life through mythical divine creatures and thus created humans. Out of this early animistic belief, came the unique Dragon-and-Phoenix culture of China. Humanism arrived with passage of time and social development. Gradually dissociated from animistic properties, jade ornaments in the shape of dragon, phoenix, tiger, or eagle, originally symbolic of a clan-family's spiritual gift, or innate virtue, took on new interpretations as Confucian gentlemen's virtues: benevolence, rectitude, wisdom, courage, and integrity.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Throughout the nearly eight-millennium development, jade carvings have first embodied the Chinese ethic of religion that was in awe of heaven and in reverence of ancestors. Then art in pursuit of verisimilitude in both form and spirit peaked after the medieval China, manifesting the academic heritage of Chinese scholars in seeking the intrinsic nature of things. The two concepts jointly attest to our national character as well as the deepest and most profound connotation of the ancient Chinese jades, the art in quest of heaven and truth.

Curio cabinet with

a meat-shaped stone “The original meaning of the word “ritual” was “to serve the gods with jade”. The earliest character for shaman (wu) tools used to draw circles superimposed at right angles"". From this we may deduce that shamans perhaps monopolized the technology for making circular pi discs, and thus had the exclusive power to present sacrifices to the gods and ancestral spirits. The round shape of the pi is said to derive from the circular path that the sun follows in the sky. The central hole of the disc represents the eternally fixed Pole Star and the principle of the “Absolute” (t’ai-chi) or “Absolute Oneness” (t’ai-i) in Chinese philosophy. In the beginning, jade pi discs and ts’ung ritual tubes were used together for sacrificial rites and at court ceremonies. Later, the kuei tablet replaced the ts’ung in this pairing. The pi was also the highest emblem of noble status as well as the most important funerary object for guiding the spirit of the deceased to heaven. Its role was so fundamental that one could say the pi permeated the entire spirit of all jade ritual systems during the classic period.

“The circular shape of the pi disc perhaps conveyed the equilibrium, symmetry, completion, and perfect beauty that the ancients saw in the path of the sun across the sky. It was also the most important ritual object for assisting in the communication with the gods and ancestors. Because of its profound cultural significance, the pi influenced the development of many classical jades. Its circular motif recurs in the arch, conical, and cylindrical forms of many other jade objects, as well as in the round spiral designs with which they are often adorned. These designs symbolize the eternal cycle of the primeval force of the universe. From accounts of a struggle between the states of Qin and Chao over a “he-shih pi disc” in 283 B.C., we know that an unblemished pi disc was not only worth the price of several cities, but that a king would fast for many days and receive the disc at a ceremony of the highest grandeur.

“Both in their shape and profound decorations on their surface, pi discs convey a yearning for immortality. The ancients who used them sought to worship the greatness of nature with objects made of a material that best embodied this quality. In high antiquity, it was believed that similar things generated an empathy between each other. Ultimately they sought to attain a state of oneness and harmony between man and nature.

Smart Carvings of Jade and Cute Use Tints

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““The earliest specimen of jade "smart" carving known to us is a three-thousand-year-old jade turtle, unearthed from the archeological site of YinXu, at Anyang. The cute little white body contrasts with its black shell, pleasingly lively, so very approachable, far from the typical alienating, esoteric impression an ancient artifact would strike on us, testifying to that "smartness" does transcend time and space. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The National Palace Museum boasts in its collections such treasured smart carvings, mostly made during the 18th and 19th centuries, including ones made of "genuine" jade (nephrite and jadeite), as well as those of agate, chalcedony, or others. Many are ingeniously fashioned using a special design technique called "cute use of tints", which takes advantage of naturally-formed color spots or areas preexisting on the material in use and transforms them into fitting parts of the intended subject.

The motifs of such carvings take on a great intriguing variety, from auspicious signs, figures or animals, to flowers and birds, sometimes even featuring vegetables and meat. Among all smart carving curios, the jadeite cabbage of Qing dynasty reigns as the most popular and impressive one, beloved of many visitors to the Museum. It embodies a perfect three-in-one union of intrinsic nature, human creativity, and symbolic significance, indeed a paramount beauty illustrating the Oneness of Nature and Human. Two items exhibited in this gallery, "Boy and Bear", "Squirrels and Grapes", are both fine examples. “Jade-like agate and jasper from the quartz family also feature varied textures and pigments, so they too are often carved with the "cute use of tints".

Jadeite Cabbage, the Meat-Shaped Stone and Jade Squirrels

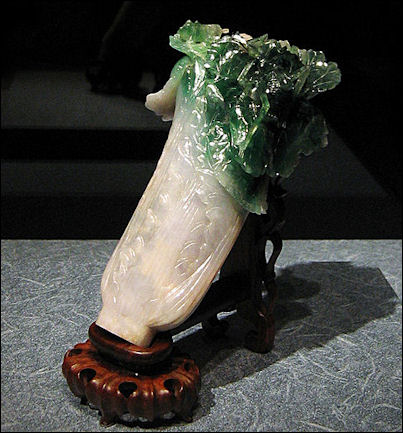

Qing period Jade cabbage

The famous meat-shaped stone of Qing dynasty (1644~1911) in the collections of the Museum is a quartz curio of jasper chalcedony. The bands of layered textures formed by the infinity of Nature are further processed by the ingenuity of Human: tight tiny holes pose as pores and also serve to prime the grain for easier dyeing. The brownish red dye "marinates" the rind in soy sauce, adding a finishing touch in the transformation of a hard, cold stone into this piece of tender, juicy, melting-right-in-mouth Dongpo pork. What a humorous pact and collaborative act between Nature and Human, a wonderfully smart carving it is. The Meat-shaped Stone, on a metal stand is 5.3 centimeters long, 6.6 centimeters wide and 5.7 centimeters high

Other interesting Qing Dynasty pieces (1644~1911) include 1) “Jadeite Squirrels and Grapes, on a wood stand (7.2 centimeters high and 5.1 centimeters wide); 2) “Jade Boy and Bear: (6.0 centimeters tall); 2) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene; 3) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene (5.1 centimeters wide; 5.9 centimeters tall); and 4) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a scene of triumph” (5.3 08 wide; 6.7 centimeters tall)

On its famous jadite cabbage, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “This jadeite, part green and part white, which is now a wonderful Chinese cabbage, would be considered mere second-rate material full of impurities if it was to be made into usual vases, jars, or ornaments, because of the cracks and blemishes that came with it. However, the artisan ingeniously transformed the rock into a lifelike vegetable of leafy green and white stems, with all unappealing rifts now hidden invisible amid the veins. And the discolored spots take on the marks of snow and frost. So with a stroke of genius, defects turn perfect. Beauty is in the detail and creativity works wonder. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“The cabbage used to be a curio item displayed in Eternal Harmony Palace, the residence quarter of Emperor Guangxu's Lady Jin. For this reason, the piece is thought to have belonged to her. Hence the inference that the "white" cabbage signifies purity or chastity of the bride, and the two insects alighting at the tips of leaves symbolize fertility: bringing a long line of imperial children to the royal family. In addition, there is a pleasant surprise in this exhibit for our visitors: the original setup of the cabbage while it adorned the Qing palace is now reenacted through a video image. It shows that the cabbage was previously "planted" in a cloisonné flowerpot as a potted landscape, quite a fancy and interesting way of display. The Jadeite Cabbage, in a cloisonné flowerpot is 5.07 centimeters long, 9.1 centimeters wide, and 18.7 centimeters tall.

Jade Sources in China

Some of the highest quality jade in China — most notably the whitish mutton fat jade — comes from an area along the banks of the Yulong Kashgar River near Hotan. Two-thousand-year-old historical records refer to a Jade Road from the area. Many gifts presented to emperor have been made with Hotan jade. One piece of Hotan mutton fat jade weighed 11,795 pounds was carved into an image of an ancient emperor leading flood control efforts. It now resides in the Forbidden City. Nephrite found in western China has traditionally been collected by "jade pickers" who wander the shores of dry river beds picking up stones washed down from the nearby Jade Mountains during the spring floods.

The Chinese switched from nephrite to jadeite when the emperors of the Qing dynasty extended the Chinese empire in the 16th century into the Yunnan Province and the Kachin State of present-day Myanmar. Kachin State is one of the world’s primary sources of jadeite. According to legend the first boulder of jadeite brought into China was carried from Kachin on the back of mule by a merchant who used the boulder to balance his load.

In 2013, a 600-ton jade rock was found in northeast China’s Liaoning Province. Xinhua reported: “The local government said that miners discovered the massive deposit of the prized material while digging in a cave in Kuandian Man Autonomous County. Given the difficulty of digging out the rock in one piece, there is no plan yet to excavate it from the cave, said Wang Xingdong, general manager of the local mining company that made the find. “The rock is priceless, Wang said. [Source: Xinhua, September 19, 2014]

Ancient Jade Sources in China

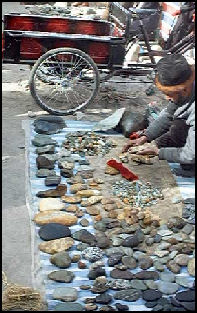

Mutton fat jade for sale

at Khotan Jade Market The sources of ancient neolithic jades is unknown. Most of the nephrite jades from the Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C) onward originated in dolomite deposits in the Kunlun Mountains in Xinjiang Province near western Tibet. Since most of this jade came from the Ho-t'ien (Hotan ) District, it was called "Ho-t'ien jade." Dark-green Chinese nephrite usually comes from the serpentined ultramafics in Tien Shan Ma Na Su in the Xinjiang Province.

The main types of jade in China and their place of origin are: 1) Hetian jade A kind of precious stone with a hardness of 6.0-6.5 degree from Hetian, Xinjiang Autonomous region. It varies greatly in color, such as white, blue, bluish white, green, yellow and black; the white one is the best. Lots of ancient Chinese jade wares were carved from it. 2) Xiu jade: A kind of serpentine with a hardness of 2.5-5.5 degree from Xiuyan, Liaoning province. Some other places in China also have this kind of stone, as Jiuquan jade from Gansu, and Xinyi jade from Guangdong. 3) Nanyang jade: A kind of plagioclase rock with a hardness of 6-6.5 degree from Dushan, Nanyang, Henan province. So sometimes it is called Dushan jade. 4) Lantian jade: a kind of serpentine from Lantian, Shaanxi province. 5) Jadeite : a kind of pyroxene with a hardness of 7 degree, mainly from Burma. It was popularly used in the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). [Source: Shanghai Museum]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ While the locations of the deposits that yielded very ancient nephritic jades aren't known, nephritic jades from the Shang Dynasty onward originate in dolomitic deposits of the Kunlun Moumtains in Xinjiang Province. As it has been collected for the most part in the Ho-t'ien District, it has been called "Ho-t'ien jade-Nephrite of this provenance appears in numerous colors. From a snowy white state in the absence of impurities, it darkens into various shades of bluish white in relation to the amounts of magnesium or iron present. An increase in the amount of ferric ion imparts a yellowish hue. When particular areas of a piece of white or bluish-white jade contain hematite, brown jade is obtained; graphite infusions, depending on their concentration lead to either grey or black jade. The fact that these two colorations frequently coexist in a given stone has been exploited by the jade craftsman. Examples of jades whose coloration and shape harmonize can be seen in the "Cup in the shape of an animal horn" and the world renowned "jade vase in the shape of a horned fish" splayed in this room. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Jadeite from Yunnan Province and northern Burma was imported in large quantities into China in the nineteenth century and quickly attracted its admirers, who continue to treasure its beauty. In summary, Chinese jade artistry boasts a long tradition, and derives much of its diversity from the differing styles and significance assumed by jades of differing periods. It is hoped that the present display will allow the viewer to experience the sheer magnificence and profundity of the ancient Chinese civilization.

Hotan Nephrite

Hotan jade accounts for about 10 percent of the annual $1.2 billion jade trade in China. Much of it is mined by small-time prospectors with sieves who hope for a big strike but get by mostly with relatively small pieces of white, green and brown jade that they can sell for a few cents a day,

In recent years the otan area has become flooded with jade prospectors, so many in fact that some people worry that the area could suffer environmental damage that could last a long time and the resource that have kept the region going for millennia could be used up. Most worrisome is the damge caused by big mining operations. According to some reports 80 percent of Hotan ‘s jade has been exploited as of 2006 and there is only enough to last for three to five more years.

A ban has been placed on mining along the Yulong Kashgar River but the ban has had little effect and mining has pretty much continued as before because local officials have been bribed by the big miners. As many a s 20,000 people and 2,000 pieces of heavy equipment continue to work the area, leaving behind strip-mine-like gashes as deep as 30 feet.

In imperial times, Hotan jades were sent as tributes to Chinese emperors and carved into exquiste works of art and made into chops used to seal official documents. The price of Hotan nephrite soared in the mid-2000s, quadrupling in value in 2007 alone to 10,000 yuan ($1,347) a gram for the best-quality stone, or 40 times the value of gold. .

Jade Miners in Khotan

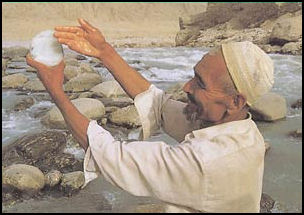

Hotan jade miner

Nephrite found in western China has traditionally been collected by "jade pickers" who wander the shores of dry river beds picking up stones washed down from the nearby Jade Mountains during the spring floods.

In the Hotan area modern miners and prospectors use a variety of methods. Some dig holes in the river banks with picks and shovels. Others dig pits with their bare hands. More sophisticated operations use bulldozers to strip mine large swaths of earth, diesel-engine power pumps to spay water on patches of dirt and rock to reveal promising pieces of rock that can be checked out further with high powered drills.

By one count around 100,000 jade miners flood the Hotan area in the peak season in the spring and summer with only a handful finding enough jade to justify the time and expense spent looking for it. One miner told the Time of London, “In the summer this whole place is black with people. If the there are 5,000 searching then maybe 100 will find some good jade — but “there’s always a chance, you never know, And the price is now so high.”

Describing a small time miner, Jane Macartney wrote in the Times of London, ‘smeared with mud and dust, men and women crouch in hollows they have dug on river banks, scratching among the boulders for a stone to make their fortune...Small time panners like Yimin Narhun...shovels out a ditch in which he can scrabble for stones while his wife and three-years-old son watch.” “I have found nothing,” the sheep farmer said. “But you never know. One good rock and my fortune is made.”

See Hotan Nephrite, Above

Jade Markets and Factories in China

Describing a makeshift jade market in Hoton, Macartney wrote in the Times of London, ‘some lay their wares on wooden bedstands: chunks of rock that look more like brown-veined stones than the stuff of dreams. Others open a fist to show a handful of pebbles from white to green to brown...Shops line the streets in Khotan, selling jade, cut into shapes from time smiling Buddha heads to shrimps, monkeys, flowers and fruit.” One shop sold a mutton-fat Buddhist figure for $13,475.

Much of China’s jade and semiprecious gems are made into jewelry and carvings in more than 2,000 small and medium-size factories in and around Shenzhen. These factories process 50,000 tons of semiprecious stone jewelry a year, 70 percent fo the world’s total.

Today, jade carvers mostly use diamond tipped equipment. In jade factories some workers cut big pieces of jade into smaller pieces. Others shape them into bangles and beads, polish them, drill holes and sting them onto earrings, bracelets and necklaces. The factories also make jewelry and other objects from onyx, turquoise other stony minerals. Buyers of jade today beware. Very little of what is sold at "jade factories" is actually jade. Often it is soapstone, agate or bowerite, and other minerals are used that are difficult to distinguish from jade without a microscope.

The factories are often sweatshops with poor ventilation and miserly managers who won’t even provide their workers with masks. In some factories the workers live in dormitories with bunk beds and without any showers or baths, requiring them to wash themselves using towels and buckets.

Boulders of jade are cut into smaller pieces with electric saws manned by workers who are paid as little as $20 a month. After a day's work they are covered in dust and look like coal miners, except the dust is green, red or yellow depending on the color of stone that has been cut. Many work without masks and develop respiratory problems, in some cases coming down with cancer or a disease called silicosis, or dust lung, while still in their early 30s. Silicosis kills more than 26,000 Chinese workers a year in professions such as mining, quarrying, gem cutting construction and shipbuilding.

Khotan Jade Boom

Jade bazaar in Hotan

Quality jade from the muddy White Jade River in Khotan is now more valuable than gold, with the most prized nuggets of mutton fat jade fetching $3,000 an ounce in 2010, a tenfold increase from a decade earlier.[Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, September 20, 2010]

A generation before some valuable jade pieces were treated as ordinary rocks. Thirty-year-old Lohman Tohti told the New York Times he recalls as a child heaving melon-size hunks into the sandbags that were used to thwart rising flood waters of the White Jade River. When Chinese buyers began arriving here in the early 1990s and the locals got wind of the stones potential value, his uncle made an enviable deal: he traded a rock the girth of a well-fed hog for a skinny cow. Today, my uncle would be a millionaire, Tohti, now a jade dealer, said with a wince.

The jade boom, , fueled by a combination of new Chinese wealth and a 5,000-year love fore the stone, turned Khotan into something of a boom town in the late 2000s and in the process turned some Khotan cotton farmers and Chinese carpetbaggers into jade tycoons. “The love of jade is in our blood, and now that people have money, everyone wants a piece around their neck or in their home,” Zhang Xiankuo, a Chinese salesman told the New York Times as he opened a safe to show off his company’s most expensive carved items, among them a pair of kissing swans that retails for $150,000 and a contemporary rendition of a Tang dynasty beauty, her breasts impertinently exposed, that can be purchased for $80,000.

Uighurs, Chinese and Jade

Unlike elsewhere in Xinjiang, Muslim Uighurs and Han Chinese seem to be getting along in Khotan with both prospering from the jade trade. The Uighurs have largely made their fortune harvesting jade from the river and selling it to Chinese middlemen. Because devout Muslims are proscribed from dealing in certain representational images, the Han have come to monopolize the carving and sale of Buddhist figurines, stalking tigers and the miniature cabbages that are popular among Chinese consumers. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, September 20, 2010]

“Jade has no meaning for our culture, but we are thankful to Allah that the Chinese go crazy for it,” said Yacen Ahmat, a Uighur who spends seven days a week working the crowds at Khotan’s jade bazaar, a busy marketplace dominated by prospectors trying to unload jade pieces on savvy wholesalers or east-to-dupe tourists.

Hu Xianli, a 59-year-old self-professed jade fanatic from eastern Zhejiang Province, told the New York Times he had been duped countless times over the years. At best, he has grossly overpaid for mediocre specimens. At worst, he has mistaken chemically treated rocks for mutton-fat beauties. A retired railway engineer, he likened his relationship with jade to an overpriced college education. “In the early years I paid a lot of tuition, but now that I’ve finally graduated, I’m not so easily fooled,” he said as a throng of overeager sellers, hands full of egg-size stones, thrust their wares into his face.

Image Sources: Mostly from the the Palace Museum in Taipei with some from the Silk Road Foundation, Wikimedia Commons, National Museum in Beijing amd the Metropolitan Museum of Art , Beifan, CNTO and BBC

Text Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021