COMMUNISM AND LITERATURE

The Communists have traditionally viewed literature primarily as a propaganda device. In a piece entitled “Yan'an Talks of Art and Literature”, Mao argued that literature was something that should be used for a revolutionary purposes. Most Communist literature is about peasants, workers and soldiers who overcome great odds to achieve great things.

The Communists have traditionally viewed literature primarily as a propaganda device. In a piece entitled “Yan'an Talks of Art and Literature”, Mao argued that literature was something that should be used for a revolutionary purposes. Most Communist literature is about peasants, workers and soldiers who overcome great odds to achieve great things.

What was expected of literature and culture in a Communist state was outlined at the Yan’an Talks on Literature and Art. Eric Abrahamsen wrote in the International Herald Tribune: “The Yan’an Talks on Literature and Art, delivered in 1942 by Mao Zedong, laid out his plan for the role of art in Chinese society. Seven years before the establishment of the People’s Republic, Mao was essentially telling artists that in a future Communist paradise they could expect to work solely in the service of the political aims of the party. It included phrases like: “The purpose of our meeting today is to ensure that literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part.” See article on CULTURE UNDER THE COMMUNISTS IN CHINA lture factsanddetails.com

Lu Xun was a central figure in how literature was defined and the limits in which it was constrained See an article on Lu Xun (factsanddetails.com. Party leaders depicted him as "drawing the blueprint of the communist future" and Mao Zedong defined him as the "chief commander of China's Cultural Revolution," After the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 the Party sought more control over intellectual life in China, and intellectual independence was suppressed, often violently. Finally, Lu Xun's satirical and ironic writing style itself was discouraged, ridiculed, then as often as possible destroyed. In 1942, Mao wrote that "the style of the essay should not simply be like Lu Xun's. [In a Communist society] we can shout at the top of our voices and have no need for veiled and round-about expressions, which are hard for the people to understand. During the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party both hailed Lu Xun as one of the fathers of communism in China, yet ironically suppressed the very intellectual culture and style of writing that he represented.

The scholars Li Tuo and Geremie Barme have described a "Mao style" or "Mao speak" that was imposed on spoken and written Chinese beginning in the 1950s as part of an effort not only to standardize the language, but to unify thinking and expression. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “It is important to remember that, for almost thirty years, when China was in its most revolutionary period (1949-1976), it was quite isolated from the rest of the world. The culture and society of China during the 1950s and 1960s were very different from anything we have known in North America and Western Europe and also very different from China today. Millions of people earnestly dedicated their lives, day in and day out, to building the “new China.” The personal and collective sacrifices they made for what was at that time seen as the “greater good” is likely to seem incredible to us today. The fiction of this period provides the ideal window into the texture of human experience under the ideology and restrictions of life in revolutionary China. The stories of Hao Ran (pronounced “How Rawn”) are most representative of this genre. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

English-language versions of English classic were widely available throughout the Maoist era, even during the Cultural Revolution when Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights were widely read. Other famous English-language classic available in China include Dickens' “A Story of Two Places and Difficult Years”, Hawthorne's “The Red Letter”, and Steinbeck's “Angry Grapes”. By the early 1990s, when almost all major works of international fiction were being translated into Chinese, novels by V. S. Naipaul and Toni Morrison were available. [Source: Paul Theroux]

Influential poets if the Mao era include Guo Moro, whose work is regarded as scholarly — yet dry and perhaps subservient — and Wen Yiduo, the Westernized and decadent poet who was assassinated in 1946 by Nationalist agents. Wen was the author of an immensely influential collection of poetry, Dead Water, which inspired the meng long (murky) poets who rekindled non-political poetry in China in the 1980s. [Source: Francesco Sisci, the Asia Editor of La Stampa, form the Asian Times]

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; MODERN CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; LU XUN: HIS LIFE AND WORKS factsanddetails.com ; LAO SHE factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST THEATER factsanddetails.com ; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; ACCLAIMED MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com YU HUA factsanddetails.com ; LIAO YIWU factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; WANG MENG factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Sources: Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) mclc.osu.edu; Mao Sayings art-bin.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Making and Remaking of China's "Red Classics": Politics, Aesthetics, and Mass Culture” by Rosemary Roberts and Li Li Amazon.com; “Popular Chinese Literature and Performing Arts in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979" by Bonnie S. McDougall Amazon.com; “Propaganda and Culture in Mao's China: Deng Tuo and the Intelligentsia’ by Timothy Cheek Amazon.com; “Creating the Intellectual: Chinese Communism and the Rise of a Classification” by Eddy U Amazon.com “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “Red Detachment of Woman: a Modern Revolutionary Dance Drama” Amazon.com “Taking Tiger Mountain by strategy;: A modern revolutionary Peking opera” Amazon.com “The Shop of the Lin Family Spring Silkworms (English and Chinese Edition) by Dun Mao (Author), Sidney Shapiro (Translator) Amazon.com; “The Song of Youth” by Yang Mo, Nan Ying, et al. Amazon.com

Literature in the Mao Era

After 1949 socialist realism, based on Mao's famous 1942 "Yan'an Talks on Literature and Art," became the uniform style of Chinese authors whose works were published. Conflict, however, soon developed between the government and the writers. The ability to satirize and expose the evils in contemporary society that had made writers useful to the Chinese Communist Party before its accession to power was no longer welcomed. Even more unwelcome to the party was the persistence among writers of what was deplored as "petty bourgeois idealism," "humanitarianism," and an insistence on freedom to choose subject matter. [Source: Library of Congress]

“At the time of the Great Leap Forward, the government increased its insistence on the use of socialist realism and combined with it so-called revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism. Authors were permitted to write about contemporary China, as well as other times during China's modern period--as long as it was accomplished with the desired socialist revolutionary realism. Nonetheless, the political restrictions discouraged many writers. Although authors were encouraged to write, production of literature fell off to the point that in 1962 only forty-two novels were published.

For many Chinese in their 50s and 60s the only reading material that was available when they were children was “The Little Red Book”. Books were hard to come by during the Cultural Revolution, or they would circulate in mutilated form, The writer Yu Hua said he read the middle of a torn copy of a novel by Guy de Maupassant (I remember it had a lot of sex, he said) without knowing its title or author. His formative reading experience was provided by the big character posters of the Cultural Revolution, in which people denounced their neighbors with violent inventiveness. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Many Chinese books that are banned in China are available outside the county, and many Chinese classics can be read in English but not Chinese. In some places Chinese still have to show a passbook to enter "special section" in bookstores and libraries with books by British and American writers such as Saul Bellow and George Orwell. Libraries are regarded as places to read books. It is nearly impossible to check out a book.

Red Classics

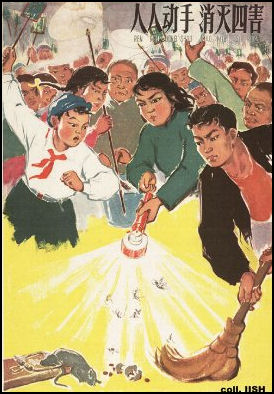

Eliminating the Four Pests After Liberation in 1949, popular Chinese pulp novels were replaced by Communist books such as “Red Star Heroes”, “We Fight Best When We March Our Hardest”, “After Reaping the Bumper Harvest” and “Grandma Sees Six Different Machines”. Party line fables like “The Foolish Man Who Removed the Mountains” were known to everyone. It was several decades before the Ministries of Truth, Propaganda and Culture allowed romantic novels about liberation soldiers who missed their girlfriends to be published.

In a review of the book “The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics”, Yizhong Gu wrote: “The origin of the term “red classics” is unclear.” The book states: “the broadest understanding of the scope of the ‘red classics’” by investigating not just literature but “films, TV series, picture books, cartoons, and traditional-style paintings”. The editors address this array of media according to three key characteristics: “their sociopolitical and ideological import, their aesthetic significance, and their function as a mass cultural phenomenon”. [Source:Yizhong Gu, University of Washington, MCLC Resource Center Publication, May, 2018)

“The first six chapters, which constitute Part I, are grouped under the theme “Creating the Canon: The ‘Red Classics’ in the Maoist Era.” In chapter 1 (translated by Ping Qiu and Richard King), Lianfen Yang compares the two versions of Wang Lin’s Hinterland , a lesser-known socialist novel. The first version of the novel was banned in the early 1950s, owing to its major theme (concerned with the “democratic constitution” ), its “naturalistic” writing style, and its loosely constructed narrative, all of which were incongruent with Mao’s “Yan’an Talks.” Wang Lin realized these problems and took about thirty years to revise the novel, making it “a standardized project that conforms to the ‘three prominences’ literary theory of the Cultural Revolution” (15). Unfortunately and ironically, when the second version reached the publisher in 1984, it was already politically out of date and doomed to oblivion.

“The novel Red Crag , the focus of chapter 3, provides an excellent case that stands opposite to the “painstaking realism” of Great Changes. Li Li traces how Red Crag, originally a piece of reportage on “real people and real events,” concealed many “historical facts” in order to be elevated as a reflection of “historical truth” (57). The protracted writing and rewriting process involved constant negotiation between three authors and the seasoned revolutionary editors. Imprisoned by the Guomindang in the late 1940s, the authors were acquainted with many soon-to-be martyrs and had garnered a considerable amount of “real-life data” while in prison. The editors, however, regarded the authors’ personal eye-witness accounts as “blood-drenched” “piles of data” (47), and they attempted to weave the “real events” into a grand narrative, according to a “prefigured and anticipated” historical truth (48). Red Crag was finally published in 1961, thanks to the senior editor Zhang Yu’s “blood transfusion” strategy of adding vivid but fictitious details and deleting real but inappropriate elements.

“Chapters 4 and 5 investigate how revolutionary content was married to traditional forms in shaping some of the “red classics.” In chapter 4 (translated by Krista Van Fleit Hang), Yang Li’s rereading of Tracks in the Snowy Forest answers a common question that many English readers may have: although “red classics” are ideologically saturated, why are many of them still popular in China today? Li argues that underlying the “revolutionary popular novels” are narrative structures and elements from pre-modern Chinese novels and folk stories that attract Chinese readers. “Tracks in the Snowy Forest wholly redeployed the narrative tactics from Journey to the West ” (62). Its popularity is also attributable to numerous elements borrowed from martial arts novels and chivalric romance that most Chinese readers would be familiar with.

“Part II, consisting of chapters 7, 8, 9 and 10, are grouped under the theme “Making over the Canon: The ‘Red Classics’ in the Reform Era.” Each chapter focuses on aspects of the transformation of themes, styles, and ideological connotations of the “red classics” from their Maoist origins to their remakes in the Reform Era. In chapter 7, Rosemary Roberts compares themes and styles of the picture storybooks genre between the two eras. The Maoist storybooks are more crude and abstract, designed to stimulate children and low-literacy readers’ revolutionary identification with the “peasants, workers, and soldiers” (123). Storybooks of the reform era, on the contrary, are more refined and detailed, so that their targeted reader group — the middle class — can “appreciate the sophisticated artistry” without necessarily identifying with the peasants (133).

Book: “The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics”: Politics, Aesthetics and Mass Culture” edited by Rosemary Roberts and Li Li (Hong Kong University Press, 2018),

Mao Dun

Mao Dun (pen name of Shen Yanbing, 1896-1981) was born in Zhejiang Province, not far from Shanghai, and educated at Beijing University. He was the first of the novelists to emerge from the League of Left-Wing Writers, a Communist Party front organization. His work reflected the revolutionary struggle and disillusionment of the late 1920s. China’s most prestigious literary prize — the Mao Dun Prize — is named after him.”

Mao Dun was an essayist, journalist, novelist, playwright, and literary and cultural critic. He served as and Minister of Culture from 1949 to 1965 under Mao Zedong and was one of the most celebrated left-wing realist novelists of modern China. His most famous work. “Midnight” was a novel depicting life in cosmopolitan Shanghai. During the period in which he was writing Midnight, Mao Dun was a close friend of Lu Xun, China's most celebrated writer at that time. Among other things he translated the works of Scottish historical novelist Walter Scott.

"Mao Dun" means "contradiction". He adopted the pen name to express the tension in the conflicting revolutionary ideology within China in the 1920s. In a review of the book “The Edge of Knowing: Dreams, History, and Realism in Modern Chinese Literature by Roy Bing Chan, Laurence Coderre wrote: One could hardly speak of realism in China without addressing Mao Dun, arguably its most ardent supporter and practitioner. Chan specifically draws our attention to Mao Dun’s “Eclipse” trilogy as well as the more substantial “Midnight”. The latter is commonly understood to be the paradigmatic attempt at a realist portrait of Chinese social and economic relations in the early 1930s.” Chan “radically reconfigures the novel’s implicit gender politics: instead of “devolving” into a fetishization of female “hysteria,” as is often alleged, the novel is recast as itself engaging in a form of (male) “hysteria.” As a result, the text’s leftist aims are not “undone” so much as manifested by its surreptitious voyeurism and anti-feminist objectification. Midnight becomes something of a monument to realism’s underlying desire to enact the real, to go beyond facile reflection, to be “a more horrifying mirror to reality than mimesis itself” (107). When reality is nightmarish — and what could be more nightmarish than semi-colonial, capitalist exploitation? — dream rhetoric turns realist.[Source: Laurence Coderre, New York University, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017; Book: “The Edge of Knowing: Dreams, History, and Realism in Modern Chinese Literature by Roy Bing Chan (University of Washington Press, 2016)]

"Spring Silkworms" by Mao Dun

In the short story "Spring Silkworms", Mao Dun addresses the situation of China’s farmers — the most numerous segment of the population, but one with which urban-based authors had little meaningful contact. Mao Dun wrote: “None of these women or children looked really healthy. Since the coming of spring, they, had been eating only half their fill; their clothes were old and torn. As a matter of fact, they, weren’t much better off than beggars. Yet all were in quite good spirits, sustained by enormous, patience and grand illusions. Burdened though they were by daily mounting debts, they had, only one thought in their heads — If we get a good crop of silkworms, everything will be all, right! … They could already visualize how, in a month, the shiny green leaves would be, converted into snow-white cocoons, the cocoons exchanged for clinking silver dollars. Although, their stomachs were growling with hunger, they couldn’t refrain from smiling at this happy, prospect. [Source: “Chinese Civilization and Society (A Sourcebook”), edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey (New York: The Free Press, 1981); Translated by Sidney Shapiro; Columbia University’s Asia for Educators www.columbia.edu

“Old Tung Pao was able to borrow the money at a low rate of interest — only twentyfive, per cent a month! Both the principal and interest had to be repaid by the end of the silkworm season. Old Tung Pao’s family, borrowing a little here, getting a little credit there, somehow, managed to get by. Nor did the other families eat any better; there wasn’t one with a spare bag, of rice! Although they had harvested a good crop the previous year, landlords, creditors, taxes, levies, one after another, had cleaned the peasants out long ago. Now all their hopes were, pinned on the spring silkworms. The repayment date of every loan they made was set for the “end of the silkworm season.” The next morning, Old Tung Pao went into town to borrow money for more leaves.

“Before leaving home, he had talked the matter over with daughter-in-law. They had decided to, mortgage their grove of mulberries that produced fifteen loads of leaves a year as security for, the loan. The grove was the last piece of property the family owned. The Silkworm Goddess had been beneficent to the tiny village this year. Most of the two dozen families garnered good crops of cocoons from their silkworms. The harvest of Old, Tung Pao’s family was well above average.

“But in the village, the atmosphere was changing day by day. People who had just begun, to laugh were now all frowns. News was reaching them from town that none of the neighboring, silk filatures was opening its doors. It was the same with the houses along the highway. Last, year at this time buyers of cocoons were streaming in and out of the village. This year there, wasn’t a sign of even half a one. In their place came cunning creditors and tax collectors who, promptly froze up if you asked them to take cocoons in payment.

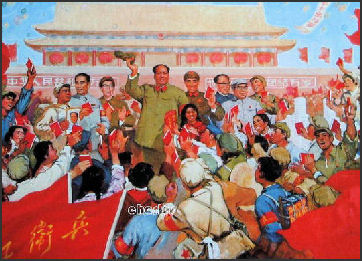

Mao with writers and artists in Yannan in 1942

Yang Mo’s Song of Youth

Yang Mo’s novel, Song of Youth, published at the height of the Great Leap Forward in 1958, was tremendously popular. Its main character is a young woman named Lin Daojing. In “Configurations of the Real in Chinese Literary and Aesthetic Modernity”, Ban Wang, Wang Hui, and Geremie Barmé write: “Song of Youth” offers us an intelligent, passionate young woman whose love of country is as strong as her philosophical commitment to the truth embodied in the law of the negation of the negation. We have few problems accounting for the theme of nationalism in such novels, but tend to regard explicit mention of the latter theoretical convictions as at best ideological window dressing to fluff up the overall socialist character of the novel. At worst, references to dialectical materialism are unintended, chilling reminders of the totalitarian system of literary and artistic control to which the socialist realist novel pays morally (and aesthetically) defeated, craven homage. [Source: In “Configurations of the Real in Chinese Literary and Aesthetic Modernity” by Ban Wang, Wang Hui, and Geremie Barmé (Brill, 2009)

In a review of the book “The Edge of Knowing: Dreams, History, and Realism in Modern Chinese Literature by Roy Bing Chan, Laurence Coderre wrote: To my mind, Chan’s greatest contribution here involves one of Mao-era literature’s most enduring conundrums: the call to combine “revolutionary realism and revolutionary romanticism.” On the surface, of course, this aesthetic mantra seems self-defeating, its constituent halves fundamentally contradictory. With the advent of socialism, however, realism and reality aren’t what they used to be; they have both turned speculative. [Source: Laurence Coderre, New York University, MCLC Resource Center Publication, March, 2017; Book: “The Edge of Knowing: Dreams, History, and Realism in Modern Chinese Literature by Roy Bing Chan (University of Washington Press, 2016)]

“If, in the works of Mao Dun, dream rhetoric finds itself in the service of the real, in the Mao era, dream and reality collapse into one another instead. Utopia is already here; reality is hallucinatory. One might therefore say that all rhetoric is dream rhetoric, though it dare not speak its name. This shift has important implications for understandings of time and temporality. Chan is especially interested in the acute temporal disjuncture effected by the “fast socialism” of the Great Leap Forward. “Fast socialism” is Maoism at its most utopian in that it pursues communism at an accelerated pace. That this pace should be fueled by overtime and sleepless nights seems fitting; there was no time, somatically or discursively, for dreams-qua-dreams, only dreams-qua-reality. In the strange liminal space such temporal compression and collective hallucination afford, instead of looking forward — utopia is now — desire is cast backward. Thus the paradoxically nostalgic thread in Yang Mo’s Song of Youth.

Cultural Revolution Literature

“During the Cultural Revolution, the repression and intimidation led by Mao's fourth wife, Jiang Qing, succeeded in drying up all cultural activity except a few "model" operas and heroic stories. Although it has since been learned that some writers continued to produce in secret, during that period no significant literary work was published.

Man He of Williams College wrote: Liu Binyan’s “Between Man and Monster” (1979) is “a celebrated work of reportage that exposed corruption at a state-run coal-mining enterprise in Heilongjiang.” It “identifies misrule by monsters, not criminals, as the problem behind the Cultural Revolution. Wang Shouxin, the female official condemned in the work, is...emblematic of the “monsters” that ruled during the Cultural Revolution, [Source: Man He, Williams College, MCLC Resource Center Publication, July, 2017]

“Dai Houying’s novel “Humanity, Ah Humanity!” (1980) is a literary testimony that “contested the conception of a rational, impersonal, and objectively existing force of justice”. He work has multiple narrators and prioritizes “psychological interiority over plot and emotions over hard facts. By reviving the genre of psychological realism, Dai probed her characters’ interiority, or more precisely their individual and emotional reactions to everyday alienation. Readers during the post-Mao transition were shown that “a truly just reckoning with the past must take full account of the complexity and individuality of human emotions”. The actualization of transitional justice did not merely rely on a story of requital; it was also rooted in the equation of “human circumstances” with “emotions”.

“Yang Jiang’s 1981 memoir, “Six Records of a Cadre School” was a widely-read work and the “the first Cultural Revolution memoir by an established author.” It focuses on routine events that took place at a May Seventh Cadre School, a rural labor camp for sent-down urban intellectuals. Yang’s multiple, fragmented, and incomplete accounts reflect the complexities of the post-Mao transition.” Yang explores the :shame that exists among all who experienced the Cultural Revolution. She was assigned the job of guarding the collected feces of the cadre school from being stolen by local peasants.

Hao Ran

Hao Ran “Hao Ran (pen name of Liang Jinguang, 1932.2008) was probably the most popular author in the People’s Republic of China during the Cultural Revolution period. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ He is the leader of his generation of writers, a generation born in the 1930s and 1940s of proletarian backgrounds who wrote for the Communist Party throughout their careers. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“ His hundreds of stories and several novels, which have sold millions of copies, had mass appeal, for they glorify the socialist revolution by depicting proletarian heroes who serve the state with self-sacrificing dedication. They are written in a lyrical style that romanticizes peasant life and values. The ideals Hao Ran illustrates are clear.cut and easy for students to grasp. Since his fiction is highly representative of official Cultural Revolution attitudes, it provides a graphic vehicle for classroom discussion of this controversial period. This type of literature was popular until 1976, when the Dissent Literature began to appear.

In a review of the book “The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics”, Yizhong Gu wrote: “In chapter 6, Xiaofei Tian compares Hao Ran’s early short stories to his works from the latter years of the Cultural Revolution. Hao Ran’s early short stories possess “a fascinating mix of socialist ideology and a raw sexual energy that refuses to be entirely subsumed by the revolutionary discourse” (95). His late works, such as “Spring Snow” , however, are “unapologetically harsh and violent, reflecting both the changed political atmosphere and Hao Ran’s personal changes” (109). Although Hao Ran’s late works conform strictly to political ideology and Tian argues that they are less energetic, fresh, and rich than his early works, Hao Ran himself, if he were alive, might not agree. Consider, for example, comments Hao Ran made during a 1998 interview, where he stated that “I have never felt regret about my previous works...Although The Golden Road emphasized class and line struggles, and downplayed some other things, it recorded people and society of that period in a truthful way.” [Source:Yizhong Gu, University of Washington, MCLC Resource Center Publication, May, 2018; Book: “The Making and Remaking of China’s “Red Classics”: Politics, Aesthetics and Mass Culture” edited by Rosemary Roberts and Li Li (Hong Kong University Press, 2018)]

"Date Orchard" by Hao Ran

"Date Orchard" by Hao Ran begins: Arriving at the date orchard, I was back in my home village, Chisu, after an absence of years. The dates were ripening. The orchard, stretching for miles around, reminded me of a bride in her wedding clothes smiling bashfully as she waited to be fetched to her husband’s home. The interlaced boughs, just beginning to lose their green leaves, were bent under thick clusters of fruit. Under the afternoon sun the dates glowed with colour: agate.red, jade.green or a mottled green and russet. The whole orchard was as pretty as a picture. Stooping, I made my way under the dense, low.hanging boughs which seemed to be stretching out to catch at my jacket, their leaves shimmying and rustling as if in welcome. I was intoxicated by the beauty around me. [Source: “Chinese Literature”, vol. 4 (April 1974): 36.48; translated by Marsha Wagner; Columbia University’s Asia for Educators afe.easia.columbia.edu

“I kept on until, in a clearing ahead, I caught sight of a whitewashed adobe wall. It was my uncle’s home, the only cottage in the date orchard and, to me, a dear, familiar sight. It was

“here that my mother had brought me as a child to avoid the Japs’ “mopping up” campaigns.

“Here that I and my comrades had held meetings and spent the night when I was old enough to join the resistance. At that time, this thatched cottage housed the provincial district office and, guerrilla headquarters. The dates served as fine nourishment for the partisans, the owner of the cottage as their guard. Here many wounded fighters recovered their strength.

“Crossing a ditch overgrown with wild flowers and grass, I saw once again the wicket, gate half hidden behind thick foliage. It was ajar. My uncle was sitting under the big spreading, date tree in the middle of his yard. We had met at the bus station the previous day and, arranged for my visit today. While waiting for me, with the deftness of long practice, he was, weaving a wicker basket. My uncle was known in these parts as a champion date.grower and a, warmhearted fellow always willing to help others with pruning or grafting. Old though he now, was, his hands had lost none of their skill. “Well, uncle, here I am!” I called, stepping in.

““So you came on foot, not by bike, eh?” He turned slowly towards me, a smile on his, wrinkled face. “Come on in. Or maybe you’d rather sit outside where it’s brighter while I go, and make you some tea.” With that he stood up, brushed the dust off his trousers and walked, stiffly but steadily into the north room.

“In his absence I looked eagerly round the quiet, secluded courtyard. A regular date.land, this was. The courtyard was shaded by date trees; strings of dates hung from the eaves of the new tiled house; windfalls were sunning in baskets and on mats on the ground. Unbuttoning, my coat, I sat down on a block of date.wood in front of the old date tree. Without warning, a, commotion broke out above me and big ruddy dates beat down on my head like hailstones. I, jumped to my feet. Before I could raise my head a fresh lot of dates rained down. As I retreated, hastily to the gateway, a mocking peal of laughter ran out from the tree.

“I looked up in annoyance. Perched there was a girl in black cloth shoes, blue trousers, rolled up to her knees and a snowy white blouse, one corner of which had caught on a branch. Her plaits, tied with pink silk bows, were swaying from side to side. But her face was hidden, from me by the dense branches. Who was this cheeky girl? She was still laughing uncontrollably. The situation was, saved by my uncle’s return with a pot of tea and some bowls. “Come down, minx! Quick!” he shouted up at her, smiling.

“Only then did the laughter stop. “I’ve been treating our visitor to dates,” the girl called, back cheerfully. The next second she had scrambled to the ground. She was a girl in her teens with fine arched eyebrows who surveyed me through, narrowed eyes, her nose slightly turned up. As she compressed her lips to hold back her, laughter, two big dimples appeared in her rosy cheeks glowing with health. She was, energetically rubbing her plump hands, perhaps because she had scraped them while climbing, the tree.

Hu Feng

Hu Feng (1902-85) is a figure well known to most students of People’s Republic of China (PRC) history but not well known to others. Gregor Benton, who translated “Hu Feng’s Prison Years”, wrote: Probably all revolutions in modern times have fallen out, sooner or later, with their intellectuals. Critical thinkers have been both the begetters of revolution, by articulating its ideologies, and its victims, for the same righteous indignation that fired them up enough to join it in the first place led many to denounce its abuses once the new freedoms vanished. [Source: Gregor Benton, professor emeritus at Cardiff University, translator of Mei Zhi’s prison memoirs “Hu Feng’s Prison Years” (2013)]

“Hu Feng is an example. He became a revolutionary at Beijing University in the 1920s, secretly joined the Japanese Communist Party in Tokyo, worked for the resistance in wartime China, and led movements of leftwing writers in cities controlled by Chiang Kai-shek. He was one of China’s best-known leftwing editors before 1949 and a pupil of Lu Xun, the giant of China’s twentieth-century literature and its George Orwell. After Mao’s victory in 1949, Hu Feng worked for a while on the fringes of the Beijing regime, but after a couple of years he got into trouble with the literary and political establishment. This was partly because he belonged to a wrong faction, but mainly because of his liberal view of literature. He implicitly criticized Mao’s proposal that creative writing should serve the party, by extolling the masses and reflecting the ‘bright side’ of life rather than ‘exposing the darkness’. So he was denounced for ‘subjectivism’, i.e., exaggerating the role played by what he called the inner energy of the active subject. He was also a belligerent man. His short fuse made enemies, and he was not a party member, unlike his opponents. He had joined its youth section in 1923, lost touch during the civil war, and tried to rejoin after returning from Japan, but failed.

Sheila Melvin wrote in Caixin Online: “Hu Feng was a product of the May Fourth Movement and a disciple of Lu Xun, a committed leftist who believed that literature should inspire social transformation and reflect reality, but who also insisted on the role of the individual in the creative process. In the lingo of the era, he supported “subjectivism” and argued that artists and writers should not be dictated to and controlled by political bureaucrats — instead, they should be granted some autonomy so they could actually be creative. [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, December 26, 2014]

“This stance earned him enemies early on — well before 1949 — but he refused to back down, instead warning that a blind insistence on obedience to Party dictates would turn China into a “cultural desert” and founding several literary journals — like “July” and “Hope” — in which he promoted the works of like-minded young writers (among them the poet Ai Qing, the father of Ai Weiwei). Hu’s beliefs became increasingly problematic after Chairman Mao gave his speech at the Yanan Forum on Arts and Literature, in which he decreed that “There is no such thing as art for art’s sake, art that stands above classes, art that is detached from or independent of politics” and after which the Party began exerting ever tighter control over writers, artists — and the individual in general. Nonetheless, Hu survived the transition to the PRC

Hu Feng Attacked and Imprisoned By Mao

Sheila Melvin wrote in Caixin Online: After reading Jonathan Spence’s “The Search for Modern China.” It stuck in my mind because back then I found it incredible that a nationwide campaign could have been launched against a lone writer who was himself a loyal member of the Communist Party, his only “crime,” in essence, to suggest that China’s creators and consumers of culture needed a little space in which to breathe. [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, December 26, 2014]

“Later, I heard Hu’s name in a more personal way from my friend and teacher Gui Biqing, because her beloved younger brother, Wang Yuanhua, had been an associate of Hu’s, both men active leftist writer/critics from Hubei working with the League of Left-Wing Writers in pre-liberation Shanghai. One day in 1955, Shanghai’s chief of police asked Wang to admit that Hu was a counter-revolutionary – warning Wang that if he did not, the consequences would be “severe.” Wang spent a long sleepless night in detention and the next day told the police chief that he did not consider Hu a counter-revolutionary. He was thus declared a member of the “Hu Feng counter-revolutionary clique” and jailed for the prime of his life; his wife was punished, too, and later, in the Cultural Revolution, even his sister, my teacher, was locked-up for eight months.

After the People’s Republic of China was created in 1949, Hu Feng “was appointed to the editorial boards of the prominent journal People’s Literature and the Chinese Writer’s Union. He used these positions to promote professionalism, criticize the nation’s stagnating intellectual life, and decry the idea that writers could only focus on the lives of workers, peasants and soldiers — didn’t other people’s lives matter, too? “

In March of 1954, he drafted a 300,000 word “Report on the Real Situation in Literature and Art Since Liberation” and submitted it to Xi Zhongxun — the father of current president Xi Jinping, who then supervised cultural policies for the Party — who reportedly welcomed it. For good measure, Hu appended a long letter to the Politburo complaining that he had been ostracized and deprived of his right to work, and asking them to intercede. Chairman Mao did not respond well. On the contrary, he personally helped launch a campaign against “Hu Fengism,” which was rolled out nationwide to drill home the dictate that every individual must subsume his will to that of the Party and the State. Members of Hu’s “clique” — most of whom he had never met — were rounded up and arrested. Hu and his wife were taken away in the middle of the night while their three young children slept — she was imprisoned for 70 months and he for 10 and a half years..

Hu Feng’s Prison Years

Gregor Benton wrote:“Hu Feng spent twenty-five years as a political prisoner starting in 1955, a record surpassed only by the Chinese Trotskyists’ thirty-odd years in gaol. After his death in 1985, his wife Mei Zhi wrote her memoir of the prison years she shared with him. Mei Zhi too was a revolutionary, but by profession she was a children’s author, so her writing is clear and jargon-free. Initially gaoled as Hu Feng’s accomplice, she was freed under supervision in 1961. The nuances of Hu Feng’s literary theory didn’t really interest her, but she stayed true to him despite the troubles he brought on her and their children and despite her milder views. She returned to prison voluntarily after her release, to care for him in his sickness and old age. [Source: Gregor Benton, professor emeritus at Cardiff University, translator of Mei Zhi’s prison memoirs “Hu Feng’s Prison Years” (2013)]

“Mei Zhi was engagingly honest about her feelings. She was a stoic, capable of astonishing self-sacrifice for her family, but unlike Hu Feng she could be cynical about politics. Hers is one of China’s best prison-memoirs. It is a gripping story, climaxing in Hu’s madness and a redemption of sorts. It differs from similar accounts in that despite their calvary, Mei and Hu remained supporters of the revolution. It is also a love story — of her love for him, even in the years of his madness.

“The book was first published in instalments, starting with Past Events Disperse like Smoke. I picked this up in Beijing in 1987 for Wang Fanxi, the exiled elderly Trotskyist leader who shared my house for several years. On my trips to China, I used to buy books I thought he’d like. It turned out he and Hu Feng had been class-mates at Beijing University, along with Wang Shiwei, Chinese communism’s first real dissident, murdered by the party near Yan’an in 1947 after arguing publicly that writing should be free to criticise party abuses and to talk about the soul. So one literature class harboured three of the party’s best-known future trouble-makers. Wang Fanxi pressed me to translate Past Events and told me some interesting facts about Hu Feng, which might have got him into trouble even sooner had his inquisitors known about them.

Sheila Melvin wrote in Caixin Online: Mei Zhi’s account opens in 1965, when she has heard nothing from her husband for a decade and fears he may be dead — but he isn’t “Out of the blue, she is informed that she can visit him at Qincheng Prison. “Ten years without ever seeing someone dear to you. What will he be like? Will he be the man of my dreams? Will I recognize him?” They talk about family and, inevitably, politics, since she is under intense pressure to make him confess and repent, even though she knows he won’t — “Hu Feng didn’t know how to play it safe and always ended up saying what he thought, so he became the victim of an unprecedented onslaught.” Hu bemoans all the people who were implicated and suffered because of him but steadfastly maintains his innocence. “I was always being told to confess but I had nothing to confess,” he tells her at one point, at another, “I have not lost faith in the Party.” [Source: Sheila Melvin, Caixin Online, December 26, 2014]

“The visits continue — she brings food, but he wants books, so she lugs him a Japanese edition of the complete works of Marx and Engels — and finally he is released. He sees his children, now grown, they celebrate Chinese New Year and plan to rebuild their lives. The reader sees the Cultural Revolution coming like an impending train wreck, but they do not. They are sent to Sichuan — for their own safety — and live in exile, carving out a life together even as they are sent to ever more remote areas. Then, in 1967, Hu is arrested again and Mei Zhi is left to fend for herself in a mountain prison camp. When Hu is returned to her five years later, he is a man broken in body and spirit, afraid even to eat a tangerine: “If I eat that, they’ll denounce me.” He leaps to attention in the middle of the night, calls himself a murderer, spy and traitor and becomes increasingly paranoid. “I would restore him,” Mei Zhi vows. She makes progress, but after the death of Zhou Enlai, which leaves him sobbing, he worsens, hearing voices talking to him through the air and threatening her with a kitchen knife while imagining he is trying to save Chairman Mao. She begs him to recover: “If you can survive, we will have won. You must live.”

“He does live, he is freed, he is exonerated. And then his body betrays him, just as his Party had, cancerous cells devouring his heart. “How he longed to stay alive!” Mei Zhi, ever faithful to the man for whom she has sacrificed so much, promises him, posthumously, to “spend the rest of my life washing the remnants of dirt from your face and showing your true features to the world!”

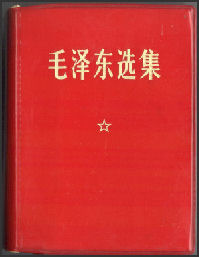

Little Red Book

Little Red Book The most widely read book in the Cultural Revolution and maybe the whole Mao period was "The Little Red Book" --- actually titled "Mao's Selected Thoughts" --- a collection of sayingsut together by Lin Biao in the Cultural Revolution. According to Time magazine, "No other book has had such a profound impact on so many people at the same time...If you read it enough it was supposed to change your brain.” Some of the passages of the Little Red Book were set to music and slogans like "Reactionaries are Paper Tigers" and "We Should Support Whatever the Enemy Opposes"! were painted everywhere on billboards and walls.

John Gray of the New Statesman wrote: “Originally the book was conceived for internal use by the army. In 1961, the minister of defence Lin Biao – appointed by Mao after the previous holder of the post had been sacked for voicing criticism of the disastrous Great Leap Forward – instructed the army journal the PLA Daily to publish a daily quotation from Mao. Bringing together hundreds of excerpts from his published writings and speeches and presenting them under thematic rubrics, the first official edition was printed in 1964 by the general political department of the People’s Liberation Army in the water-resistant red vinyl design that would become iconic. [Source: John Gray, New Statesman, Cultural Capital Blog, May 24, 2014]

“By the time the Red Guard publication appeared, Mao’s Little Red Book had been published in numbers sufficient to supply a copy to every Chinese citizen in a population of more than 740 million. At the peak of its popularity from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, it was the most printed book in the world. In the years between 1966 and 1971, well over a billion copies of the official version were published and translations were issued in three dozen languages. There were many local reprints, illicit editions and unauthorised translations. Though exact figures are not possible, the text must count among the most widely distributed in all history.” In the view of historian Daniel Leese, the volume “ranks second only to the Bible” in terms of print circulation. \=\

See Separate Article CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE: OPERAS, MANGOES AND THE LITTLE RED BOOK factsanddetails.com

Mao Slogans

Mao is considered the greatest slogan writer who ever lived although many of the slogans attributed to him were written by Lin Biao. During the Great leap Forward.Mao's followers were expected to chant, "Long live the people's communes!" and "Strive to complete and surpass the production responsibility of 12 million tons of steel!"

A famous poem from “The Little Red Book”, taken from earlier Mao speeches, that produced a several slogans went:

“A revolution is not a dinner party

Or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery

It cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle,

So temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous.

A revolution is an insurrection,

An act of violence by which one class overthrows another. “

The three main "Rules for Discipline" for soldiers and party workers in “The Little Read Book” were: "Obey orders in all your actions; Do not take a single needle or thread from the masses; and Turn in everything captured." Loyal Communists were also urged to "speak politely; return everything you borrow; don't swear at people; and do not take liberties with women."

On the topic of violence and revolution: 1) "Power grows out of the barrel of a gun." 2) "In order to get rid of the gun, it is necessary to take up the gun." 3) "Politics is war without bloodshed, while war is politics with bloodshed." 4) "When human society advances to the point where classes and states are eliminated, there will be no more wars." 5) “Fight no battle you are not sure of winning.”

Other famous sayings from “The Little Red Book” include, 1) "Modesty helps one go forward, whereas conceit makes one lag behind;" 2) "Investigation may be likened to the long months of pregnancy, and solving a problem to the day of birth. To investigate a problem is, indeed, to solve." And, 3) "People of the world, unite and defeat the U.S. aggressors and all the running dogs...Monsters of all kinds shall be destroyed."

Mao Zedong once said, There is no construction without destruction. Destroy first, and construction will follow. He extolled their Chinese peasantry for the blankness, observing that one can write beautiful things on a blank sheet of paper. On the matter of equal rights, Mao said "women hold up half the sky." In regard to population growth, Mao said, "every mouth comes with two hands." The population of China doubled under his leadership.

Mao reportedly once said that a loud fart is better than a long lecture. He shocked Kissinger by jokingly informing him that China was planning to send 10 million Chinese women to the United States. Mao told Nixon, "People like me sound a lot of big cannons. For example, things like, 'the whole world should unite and defeat imperialism, revisionism, and all reactionaries and establish socialism.” He then broke into a fit of laughter.

Literature in the Post-Mao Period

The arrest of Jiang Qing and the other members of the Gang of Four in 1976, and especially the reforms initiated at the Third Plenum of the Eleventh National Party Congress Central Committee in December 1978, led more and more older writers and some younger writers to take up their pens again. Much of the literature discussed the serious abuses of power that had taken place at both the national and the local levels during the Cultural Revolution. The writers decried the waste of time and talent during that decade and bemoaned abuses that had held China back. At the same time, the writers expressed eagerness to make a contribution to building Chinese society. This literature, often called "the literature of the wounded," contained some disquieting views of the party and the political system. Intensely patriotic, these authors wrote cynically of the political leadership that gave rise to the extreme chaos and disorder of the Cultural Revolution. Some of them extended the blame to the entire generation of leaders and to the political system itself. The political authorities were faced with a serious problem: how could they encourage writers to criticize and discredit the abuses of the Cultural Revolution without allowing that criticism to go beyond what they considered tolerable limits?[Source: Library of Congress]

“During this period, a large number of novels and short stories were published; literary magazines from before the Cultural Revolution were revived, and new ones were added to satisfy the seemingly insatiable appetite of the reading public. There was a special interest in foreign works. Linguists were commissioned to translate recently published foreign literature, often without carefully considering its interest for the Chinese reader. Literary magazines specializing in translations of foreign short stories became very popular, especially among the young.

“It is not surprising that such dramatic change brought objections from some leaders in government and literary and art circles, who feared it was happening too fast. The first reaction came in 1980 with calls to combat "bourgeois liberalism," a campaign that was repeated in 1981. These two difficult periods were followed by the campaign against spiritual pollution in late 1983, but by 1986 writers were again enjoying greater creative freedom.

Image Sources: Amazon, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021