CULTURE UNDER THE COMMUNISTS IN CHINA

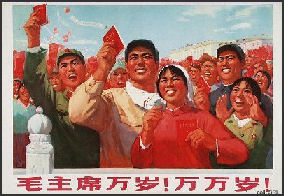

Culture under the Communists has been governed by censorship, ideological controls and the production of works to meet the needs of the state. Since Mao’s time the government has controlled movies, fine arts and books, carefully selecting what people have been exposed to. Mao once said, "There is no such thing as art for art's sake, art that stands above the classes or art that is detached from or independent of politics."

Culture under the Communists has been governed by censorship, ideological controls and the production of works to meet the needs of the state. Since Mao’s time the government has controlled movies, fine arts and books, carefully selecting what people have been exposed to. Mao once said, "There is no such thing as art for art's sake, art that stands above the classes or art that is detached from or independent of politics."

The government censors the output of all artists; it is forbidden to produce work that criticizes the Communist Party or its ideals.While providing support to writers, this system also suppresses their creative freedom. As the economy has become more open, however, the government has decreased its support, and artists are becoming more dependent on selling their work. Among the government bodies that monitor, oversee and fund the arts are the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Radio, Film and the Ministry of Truth and Propaganda of the Central Committee. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The Communist wanted art, literature and the media to promote Communism, Socialist thought and party goals. Works of art that didn't fit this criteria were often destroyed. Even today, Bibles, skin magazines and novels by controversial writers are confiscated at the borders.

A Ministry of Culture was established by the Communists and it was given far reaching powers to monitor and oversee all art forms and media — literature, music, art, film, television, radio, newspapers, magazines. Entertainers were trained in state schools rather than through apprenticeship as was the norm in the past.

Traditional Chinese arts have suffered under Communist rule. For a long time arts organizations, orchestras and opera companies were essentially run the same way as steel factories with the government paying for everything and controlling everything. Salaries for everybody from the directors to the janitors was paid by the government. Ticket sales didn’t matter from a financial point of view because everything was subsidized. One orchestra director told the New York Times, “There as no such thing as marketing, The government gave us a performance plan and we did it."

Mao once said, “there is no such thing as art for art’s sake.” It is now ironic then that he is the object of so much modernist art and kitsch.

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CULTURE AND PERFORMING ARTS factsanddetails.com ; INTELLECTUALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CENSORSHIP IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REFORM IN CHINA AND CRACKDOWNS UNDER XI XINPING factsanddetails.com ; ART AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com; FILM AND ACTORS factsanddetails.com; TELEVISION AND MEDIA factsanddetails.com; INTERNET AND COMMUNICATIONS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Popular Chinese Literature and Performing Arts in the People's Republic of China, 1949-1979" by Bonnie S. McDougall Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art”: A Translation of the 1943 Text with Commentary” (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies) by Bonnie S. McDougall and Zedong Mao Amazon.com; Also see Talks At The Yenan Forum On Literature And Art in “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 4" (1941-1945) Amazon.com; “Propaganda and Culture in Mao's China: Deng Tuo and the Intelligentsia’ by Timothy Cheek Amazon.com; “My Family: a Normal Intellectual Family Suffered under the Rule of the Communist Party of China” by Luowen Yu Amazon.com ; “Chinese Propaganda Posters” by Anchee Min and Stefan R. Landsberger Amazon.com; “Creating the Intellectual: Chinese Communism and the Rise of a Classification” by Eddy U Amazon.com “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “Red Detachment of Woman: a Modern Revolutionary Dance Drama” Amazon.com “Taking Tiger Mountain by strategy;: A modern revolutionary Peking opera” Amazon.com “The Little Red Book; Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung:” by Mao Tse-Tung Amazon.com; “The Party and the Arty in China: The New Politics of Culture” by Richard Curt Kraus Amazon.com

Yanan (Yenan) Forum

New Youth magazine

The Yan'an Forum on Literature and was held in May 1942 at the city of Yan'an (Yenan) in Communist-controlled China. It is remembered most for the speeches given by Mao Zedong, later edited and published as Talks at the Yan'an Forum on Literature and Art, which addressed the role of culture, literature, propaganda and art in a Communist state. The two main points were that: 1) all art should reflect the life of the working class and considering them as the main audience (“Serve the People” as Mao would say in a 1944 speech), and 2) art should serve politics, and specifically the advancement of socialism. [Source: Wikipedia]

During the Long March (1934-1935), the Communist Party and People's Liberation Army used song, drama, and dance to win support from the civilian population, but did not have a unified cultural policy. At the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) anti-Japanese themes were predominate. In 1938, the Chinese Communist Party established the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts in Yan'an to train people in literature, music, fine arts, and drama.

In 1940, Mao issued a policy statement in his tract, "On New Democracy" in which he said “China's new culture at the present stage is... the anti-imperialist anti-feudal new democracy of the popular masses led by the culture and thought of the proletariat". During the Yan'an Rectification Movement (1942-1944), the Party used various methods to consolidate ideological unity among cadres around Maoism (as opposed to Soviet-style Marxism–Leninism). The immediate spur to the Yan'an talks was a request by a concerned writer for Mao Zedong to clarify the ambiguous role of intellectuals in the Communist movement.

Yan'an Forum was a three-week conference at the Lu Xun Academy, whose objectives were to define the methods of creating Communist art. The "Yan'an Talks" outlined the party's policy on "mass culture" in China, which was to be "revolutionary culture".This revolutionary style of art would portray the lives of peasants and be directed towards them as an audience. Mao scolded artists for neglecting "The cadres, party workers of all types, fighters in the army, workers in the factories and peasants in the villages" as audiences, just because they were illiterate. He was particularly critical of Chinese opera as a courtly art form, rather than one directed towards the masses. However, he encouraged artists to draw from China's artistic legacy as well as international art forms in order to further socialism. Mao also encouraged literary people to transform themselves by living in the countryside, and to study the popular music and folk culture of the areas, incorporating both into their works.

One immediate change that resulted from the Yan'an Talks was the recognition of folk styles, particularly in music, as legitimate art forms.. Key quotations from "Yan'an Talks" form heart of the "Culture and Art" section of the Little Red Book (“Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong”). The Gang of Four's dramatic interpretation of the Yan'an Talks during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) gave birth to Party-sanctioned political art and revolutionary opera. At the same time, some Western art, including the music of of Beethoven, Dvorak, and Chopin, were condemned as "bourgeois decadence". After Mao’s death in 1976, the Yan'an talks were officially reevaluated and downgraded with the 1982 statement that "literature and art are subordinate to politics" was an "incorrect formulation", but it reaffirmed the idea that art should reflect the reality of the workers and peasantry.

Talks at the Yanan Forum on Literature and Art

In his speech at the opening of the Yan'an Forum on May 2, 1942, Mao Zedong said begins: Comrades! You have been invited to this forum today to exchange ideas and examine the relationship between work in the literary and artistic fields and revolutionary work in general. Our aim is to ensure that revolutionary literature and art follow the correct path of development and provide better help to other revolutionary work in facilitating the overthrow of our national enemy and the accomplishment of the task of national liberation.[Source and Full Text: Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, transcription by the Maoist Documentation Project. revised 2004 by Marxists.org marxists.org

In our struggle for the liberation of the Chinese people there are various fronts, among which there are the fronts of the pen and of the gun, the cultural and the military fronts. To defeat the enemy we must rely primarily on the army with guns. But this army alone is not enough; we must also have a cultural army, which is absolutely indispensable for uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy. Since the May 4th Movement such a cultural army has taken shape in China, and it has helped the Chinese revolution, gradually reduced the domain of China's feudal culture and of the comprador culture which serves imperialist aggression, and weakened their influence. To oppose the new culture the Chinese reactionaries can now only "pit quantity against quality". In other words, reactionaries have money, and though they can produce nothing good, they can go all out and produce in quantity. Literature and art have been an important and successful part of the cultural front since the May 4th Movement. During the ten years' civil war, the revolutionary literature and art movement grew greatly.

In our struggle for the liberation of the Chinese people there are various fronts, among which there are the fronts of the pen and of the gun, the cultural and the military fronts. To defeat the enemy we must rely primarily on the army with guns. But this army alone is not enough; we must also have a cultural army, which is absolutely indispensable for uniting our own ranks and defeating the enemy. Since the May 4th Movement such a cultural army has taken shape in China, and it has helped the Chinese revolution, gradually reduced the domain of China's feudal culture and of the comprador culture which serves imperialist aggression, and weakened their influence. To oppose the new culture the Chinese reactionaries can now only "pit quantity against quality". In other words, reactionaries have money, and though they can produce nothing good, they can go all out and produce in quantity. Literature and art have been an important and successful part of the cultural front since the May 4th Movement. During the ten years' civil war, the revolutionary literature and art movement grew greatly.

That movement and the revolutionary war both headed in the same general direction, but these two fraternal armies were not linked together in their practical work because the reactionaries had cut them off from each other. It is very good that since the outbreak of the War of Resistance Against Japan, more and more revolutionary writers and artists have been coming to Yenan and our other anti-Japanese base areas. But it does not necessarily follow that, having come to the base areas, they have already integrated themselves completely with the masses of the people here. The two must be completely integrated if we are to push ahead with our revolutionary work. The purpose of our meeting today is precisely to ensure that literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part, that they operate as powerful weapons for uniting and educating the people and for attacking and destroying the enemy, and that they help the people fight the enemy with one heart and one mind. What are the problems that must be solved to achieve this objective? I think they are the problems of the class stand of the writers and artists, their attitude, their audience, their work and their study.

The problem of class stand. Our stand is that of the proletariat and of the masses. For members of the Communist Party, this means keeping to the stand of the Party, keeping to Party spirit and Party policy. Are there any of our literary and art workers who are still mistaken or not clear in their understanding of this problem? I think there are. Many of our comrades have frequently departed from the correct stand.

Full Text of Talks at Yan Forum: Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, transcription by the Maoist Documentation Project. revised 2004 by Marxists.org marxists.org

In his speech at the conclusion of the Yan'an Forum on May 23, 1942, Mao Zedong said : Comrades! Our forum has had three meetings this month. In the pursuit of truth we have carried on spirited debates in which scores of Party and non-Party comrades have spoken, laying bare the issues and making them more concrete. This, I believe, will very much benefit the whole literary and artistic movement.

In discussing a problem, we should start from reality and not from definitions. We would be following a wrong method if we first looked up definitions of literature and art in textbooks and then used them to determine the guiding principles for the present-day literary and artistic movement and to judge the different opinions and controversies that arise today. We are Marxists, and Marxism teaches that in our approach to a problem we should start from objective facts, not from abstract definitions, and that we should derive our guiding principles, policies and measures from an analysis of these facts. We should do the same in our present discussion of literary and artistic work...

Impact of Mao Zedong’s 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum

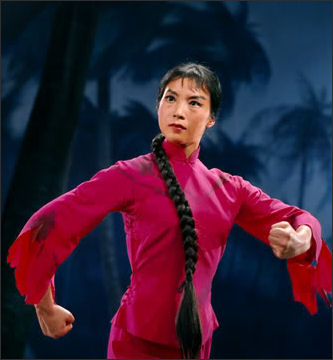

Old version of

Red Detachment of Women

Nobel-Prize winner Chinese writer Mo Yan said that Mao Zedong’s 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” is “a historical document whose existence is a matter of historical necessity.” In his speech, Mao Zedong said, "Proletarian literature and art are part of the whole proletarian revolutionary cause; they are, as Lenin said, cogs and wheels in the whole revolutionary machine." As a result, Mao demanded writers in the socialist regime write for the masses: "China’s revolutionary writers and artists, writers and artists of promise, must go among the masses; they must for a long period of time unreservedly and whole-heartedly go among the masses of workers, peasants and soldiers, go into the heat of the struggle. Only then can they proceed to creative work." Not any kind of creative work, but work that serves the "proletarian revolutionary cause."

Charles Laughlin of the University of Virginia wrote: “We teach Mao’s “Talks” not only in my “Introduction to Modern Chinese Literature,” but also in our much broader survey “East Asian Canons and Cultures,” designed and taught by my colleague in traditional Japanese literature, Gustav Heldt. Mao’s “Talks” played a key role in the formation of the modern Chinese literary canon; as Mo Yan puts it, the new writers of the 1980s were very much focused on breaking through the limitations the “Talks” placed on literature, and yet there is still much in the “Talks” that he can accept. [Source: Charles Laughlin, MCLC List, October 12, 2012]

Mao’s “Talks” does not lay down rules that must be obeyed, nor does it prescribe torture, incarceration, ostracism or death as penalties for disobedience. It is clear that Mao was concerned with discipline among intellectuals in Yan’an, and we know that he held the Forum as a pretext for criticizing Ding Ling, Wang Shiwei and other intellectuals who Mao thought were getting out of line. Wang was even executed, presumably for ideological sins, but it would be a mistake to lay the blame for the violence of Rectification on Mao’s “Talks.” The Forum and Mao’s “Talks” were political theater, meant to lend the appearance of interactivity, if not democracy, to the Rectification campaign. [Ibid]

The interesting thing about Mao’s “Talks,” though, from today’s perspective, is that in them, Mao emphasizes how writers who have come to Yan’an from all over China during World War II were entering into a new, unfamiliar rural environment, and that new literary works should reflect that change of space. They should abandon the environment of urban life, themes of social disintegration, and bourgeois consciousness that characterized much Chinese literature of the 1930s. Mao insisted that writers immerse themselves in this rural world and to look at China through the eyes of peasants. The new literature should abandon negativity and emphasize politically heroic characters and more optimism for the future. While this often led to insipid literature, it also had much in common with 1938 Nobel Prize for literature winner Pearl Buck’s way of writing China, and also something in common with Mo Yan’s rural fictional world. [Ibid]

Other see “Talks” in more sinister terms.Perry Link wrote in the NY Review of Books, “Talks” were the intellectual handcuffs of Chinese writers throughout the Mao era and were almost universally reviled by writers during the years between Mao’s death in 1976 and the Beijing massacre in 1989. Mo Yan has been widely condemned for saying the “Talks,” in their time, had “historical necessity” and “played a positive role.” [Source: Perry Link, NY Review of Books, December 6, 2012]

Artists and Writers in China Under the Communists

Mao persecuted intellectuals or tolerated them depending on his mood and political goals. Deng tolerated them as long as they towed the party line. In recent years the arts remain under tight government control but at the same time they have also opened up a lot, especially art.

Artists, writers, scientists and intellectuals who towed the party line have been endorsed and supported by the government. To gain membership to special unions and organizations they had to study at certain approved schools and create works which fit into parameters set by the government. Without government endorsement they were nobodies.

According to Communist theory, the duty of the Communist party when it comes to the arts is to maintain that there is a correct number of artists and writers for society's needs and follow the party line. Artists, musicians and writers are required to submit their work to censors before it was allowed to be presented to the public.

Artists and writers recognized by the government receive a salary, supplies, comfortable private homes or apartments, spacious offices or working space, other perks and markets for their works. Unofficial artists have to support themselves by other means. Boiler room supervisory jobs have traditionally been sought after because they worked 24 hours straight and then had three days off.

Mao with writers and artists in Yannan in 1942

Cultural Revolution Culture

The Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976 was a time of great upheaval in China. Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife, dominated cultural productions during the Cultural Revolution, The ideas she espoused through eight "Model Operas" were applied to all areas of the arts. These operas were performed continuously, and attendance was mandatory. Proletarian heroes and heroines were the main characters in each. The opera "The Red Women's Army" was a story about women from south China being organized to fight for a new and equal China. Ballet shoes and postures were used. Jiang Qing emphasized "Three Stresses" as the guiding principle behind these operas. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

China has a long tradition of yingshe, “shadow assassination,” in which writers use allegory to criticize high officials. The Cultural Revolution was, in fact, directly triggered by such suspicions: in 1965, a historical drama written by a Party intellectual was accused of being an oblique attack on Mao. The charge was absurd, but Mao took it seriously; he ordered the newspapers to denounce the au thor (who eventually died in custody, having been beaten), and the self-fuelling paranoia grew into a frenzied nationwide campaign.

Mao’s wife Jiang was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. They destroyed old movies and replaced them with new ones which were allowed to depict only eight revolution-related themes. Worker committees took over the studios and many administrators and actors were labeled as "devils and monsters" and dismissed and harangued. Even children's puppet theaters were closed down for being counter-revolutionary.

One of the objectives of the Cultural Revolution was to "socially purify" the arts.The popular play that many scholars say triggered the entire Cultural Revolution — “The Dismissal of Hai Rui from Office” — was a drama by historian Wu Han about an obscure Song dynasty official. The play was widely seen as as a traitorous critique of Mao's dismissal of Peng Dehuai, a military leader who criticized the Great Leap Forward.

Poets, artists and opera singers were imprisoned and exiled. Pop music was banned for being capitalist "poison" and Beijing Opera troupes were disbanded because they fit into the category of the "Four Olds." Among the banned writers were Aristotle, Plato, Shakespeare, Balzac, Jonathan Swift, Victor Hugo, Dickens and Mark Twain. The most widely read book was “The Little Red Book”. See Little Red Book

During the Cultural Revolution “vital and numerous love songs came under heavy fire” due to the suppression of folk songs devoid of overt politcal content. A major propaganda campaign was launched in 1973, which mobilized the masses against such widely ranging objects of attack as Lin Biao, the teachings of Confucius, and cultural exchanges with the West. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

See Separate Article CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE: OPERAS, MANGOES AND THE LITTLE RED BOOK factsanddetails.com

Impact of the Cultural Revolution on Chinese Culture

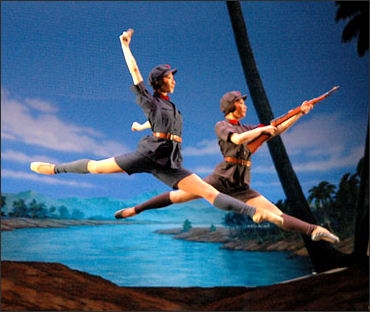

Old version of

Red Detachment of Women

Denise Y. Ho told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “In the past, Cultural Revolution culture has been easy to dismiss. Despite Western fascination will objects that we might call “Mao kitsch” — buttons, statues, and posters — and Chinese nostalgia for Cultural Revolution music or plays, we have written off these cultural products as “just propaganda,” or not really culture at all. Recent scholarship has tried to change this view. One historian has suggested that the Communist Party created its own political culture, and that this was a key source of its legitimacy. Others have examined the art and music to show how Cultural Revolution culture was a modernization of both Chinese and Western traditions, part of a much longer project. Still others have focused on audience reception of these works, which could produce meanings beyond their propaganda messages.[Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook,Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016 ~]

Explaining how the Cultural Revolution led to blossoming of artistic experimentation and intellectual dissent after the movement was over. Guobin Yang, a sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times: After the former Red Guards and other Chinese youth “were sent down to villages from late 1967, disillusionment deepened. They also saw a China unknown to them before, very poor and harsh. Many people used family connections or feigned illness to try to move back to cities. The more intellectually oriented ones thought and wrote about their experiences in poems, stories, letters and diaries. Throughout the ’70s, people like the now famous painter Xu Bing practiced their art after a day’s labor tilling the fields. Some entertained themselves by circulating hand-copied manuscripts of spy stories or erotic literature. Others took to singing romantic songs, especially Russian folk songs. The most apolitical kind of activity, like singing a love song, was an expression of political dissent, because it was a rejection of politics when politics was supposed to be “in command” of everything. “These were small things, small but happening more and more often, in more and more places. Together, they made up the undercurrent that eroded the ideology of the Cultural Revolution and primed Chinese society for radical economic and political change when opportunities arose. [Source: Chris Buckley, Sinosphere, New York Times, June 15, 2016].

The national university entrance examination was reintroduced in 1977 in China after it was abolished in 1966 at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution. The resumption of the national university entrance examination in 1977 is extraordinary in that it shaped the dreams and aspirations of millions of youth in China. However, its importance has often been overlooked. From 1972 to 1976, China's colleges started to enroll new students, and most of them were recommended by local officials based on their families' backgrounds and their own behaviors in the countryside rather than intelligence. Those who were enrolled were called worker-peasant-soldier students.” [Source: Zhang Fang Global Times, April 21 2009]

In 1977, Deng Xiaoping declared that the university entrance would be based on examination scores, thus reinstituting the admissions test officially known as the National Higher Education Entrance Examination. There were more than 10 million young candidates registered for the examination in the winter of 1977. The youngest examinees were in their early teens and, the oldest in their late thirties, and this became a major turning point for the millions of people born in the 1950s. Some of the most famous people today in China — directors Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige (known for Yellow Earth) — had taken the entrance exam in1977.

Culture After Mao

Since the late 1970s, when China began to turn its back on Maoist totalitarianism, the country has gone through several cycles of relative tolerance of dissent, followed by periods of repression.After the Cultural Revolution artists and performers that survived resurrected their art forms. Restrictions were loosened. The period from the late 1970s through the mid-1980s was considered by some to be a “high tide" for the arts, as pent up frustration that built up during the Cultural Revolution was released.

New version of

Red Detachment of Women The intellectual climate was relaxed under Deng Xiaoping, who realized that he needed the cooperation of intellectuals if his reforms were to fully take hold. Banned books by J.D. Salinger, Allen Ginsberg and Gabriel Garcia Marquez appeared. Modern art exhibitions were held State-supported intellectuals were given a salary, health care, house and opportunities to go abroad. There was a great burst of creativity. Works that addressed China’s dark side and the injustices of the Cultural revolution appeared.

Decline set in as the Deng reforms began taking hold and making money was given precedence over creativity and expression. The arts were dealt another blow after Tiananmen Square in 1989 when restrictions on all forms of expression were tightened. The Tiananmen massacre destroyed the tenuous bond between the Party and the intellectuals: some renounced their Party membership and broke with the regime; some went into exile or were jailed.

Jiang Zemin launched a "Spiritual civilization" campaign in the mid-1990s with a 15,000-word directive that aimed not only to crack down on criticism of the Communist party but also on anything that encouraged "social vices" or made people "doubt the future of socialism." With language that was reminiscent of Cultural Revolution slogans, the directives exhorted to become "soul engineers" battling people who "pander to low tastes." Pulp novelists were banned, foreign programs on Chinese television were criticized and journalists were encouraged to be "engineers of people's minds."

A commentary in the People's Daily said that some artists and writers are "bent on describing normal people's trivial affairs, tempests in teacups, even to the point of including bedroom scenes. Not only did the works of some artists lose their ideals and sink into moral depravity they even went so far as to ridicule noble values and promote the worship of hedonism and extreme individualism. This situation cannot but draw the proper attention and anxiety.”

Opening Up During the Deng Period in the 1980s and 90s

In the 1980s and 90s, following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the Chinese Government embarked on a modernization drive that included the policy of "kaifang" (opening to the outside world), creating a period of tremendous cultural ferment, the likes of which had been seen since the early years of the 20th century when China tried to rapidly assimilate an influx of foreign ideas. At the same time, conservative members of the old guard and bureaucrats — wary of modernity and tied to the past — still occupied key positions of power, creating a continuing tension between the new and the old, between the urge to rejoin the international community and the wish to isolate China from its dangerous influences. [Source: U.S. State Department report, December 1996 ]

The impetus to modernize China culturally and economically stemmed, in part, from the desire of China to regain the position of influence it once held in Asia and the world. The civilization and culture that developed there in the second millennium B.C. eventually came to dominate virtually all of East Asia, including Japan and Korea. After the Communist takeover in 1949, however, many aspects of traditional Chinese culture disappeared and society itself was drastically altered by the socialist transformation of China.

In 1982, a couple years after the Cultural Revolution ended, there were only 100 or so graduating art majors in the whole country. Today there are around 260,000. The revolutionary Stars Group was formed in the late 1970s. The relatively free-wheeling 1980s is regarded by some as a sort of golden age of Chinese modern art. Many critics argue that more innovative works emerged during that period than during the painting boom that followed when artists became more commercially aware and made “a fortune manufacturing machines to read credit cards.” Artists from the influential 1985 New Wave include Wang Guangyi, Xu Bing, Geng Jianyi and Hunag Yongping. Some of their works are clearly copies of Picasso, Munch and the Dada artists but others are original and offer insight in what Communist China was like as it was emerging from the Cultural Revolution. Prior to the violent suppression of the Democracy Movement in June 1989, China's international cultural exchanges had been flourishing. China signed formal cultural agreements with many nations, including the U.S. Private sector exchanges, such as those carried out by People to People, Sister City and Sister State programs, and U.S. universities, were too numerous to count. Hundreds of performing and visual artists; scholars of politics, economics, law, and literature; and interested citizens representing a full spectrum of professions came to China from the U.S. every month. Thousands of Chinese, too, traveled to the U.S. under government and private auspices to enhance their expertise and make contacts in the international cultural community. After Tiananmen massacre Western cultural influence was viewed more skeptically by Chinese officials, and their support for international exchange became more selective.

Cultural life of China took place under the watchful eye of a variety of organizations, including the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee, the Ministry of Culture, the All-China Federation of Literary and Art Circles, and the local offices of these national organizations. During the period after Mao’s death in 1976, China restored many cultural institutions damaged by the Cultural Revolution and rehabilitated many artists and writers. However, the government's once-substantial support for the arts was sharply reduced because of budget constraints and a policy of decentralization. Many cultural organizations, art schools, and performing arts groups were told to become self-supporting. The full effect of the new policies forced cultural institutions to grapple with financial and artistic problems they had not faced since before 1949.

Under the policy of opening to the outside world, international cultural exchanges flourised. Many countries, including the U.S., signed formal cultural agreements with China, but it was the private sector that showed the most rapid growth. Privately arranged cultural exchange activities were too numerous to count. Through them, numerous foreign performers and teachers of art, music, dance, and drama visited China; art exhibits were exchanged; and many Chinese artists went abroad. This has had a profound impact on Chinese arts, but this Western influence is not without controversy. The interest of Chinese artists in Western literature and art is upsetting to those with traditional ideas. Some avantgarde or politically sensitive works continue to be banned and their authors silenced.

Less Government Support of the Arts in Post-Mao China

In his book the “The Party and the Art in China”, Richard Krause wrote: “By 1992 the Party had given up trying to purge all dissident voices and opted instead for the strategy of urging all arts organizations to strive to earn money.” Those that worked with the system could expect to be rewarded with high posts, raises and be well paid for their teaching. Those that found success in the market place could possibly become very rich. Those that rebelled against the system could expect to be punished. In this way artists censored themselves.” Artists, directors and writers that that raised the ire of censors and authorities were not sent to jail or re-education camps, they are simply not given work and deprived of opportunities to make money. The internationally-known artist Ai Weiwei told the New York Times, “People are really selling their talent in a way that can make them money. They really know if they work with the government, they’ll benefit.”

Old version of

Red Detachment of Women Although China’s government pushed for a more market-oriented approach to performing arts, many theaters and arenas rely heavily on the China Arts and Entertainment Group, which is essentially a state-owned company that finances many foreign productions coming to the country, helps send Chinese performers abroad and organizes events like the Beijing Music Festival.” [Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, July 9, 2010]

A group was formed in 2005 by merging two government agencies, and is overseen by the Culture Ministry. It is financed by China’s cabinet, called the State Council. It arranged a credit line of as much as 1 billion renminbi ($147 million), from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. But China Arts and Entertainment is not giving out its money liberally. Some venues have an operating budget from the government but has to rely on sponsorships and ticket sales for programming.

Sponsorship to support the performing arts was still in its infancy in China in the early 2000s. Western multinational companies, which often sponsor arts programs in their home nations, are more likely to offer money than are Chinese companies. China Merchants Bank and China Construction Bank are among Chinese companies that have started to sponsor performances and more are showing interest.

Politics and the Arts in China

“The Party and the Arty in China: The New Politics of Culture“ By Richard Curt Kraus is a book that examines the relationship of politics and the arts in the Mao and Deng eras and today. In his review of the book, Oxford’s Matthew D. Johnson wrote: “” The Party and the Arty in China“ is bursting with insights that are at odds with nearly all conventional (read: journalistic) wisdom concerning cultural and artistic life in the People's Republic.” [Source: Matthew D. Johnson, University of Oxford MCLC Resource Center]

“As Kraus himself states, one goal of this new work is to counteract “idealist myths ... of the artist as a heroic figure, locked in constant struggle against repressed and repressive authority” . Using perspectives from political science, sociology, and history, he draws together observations accumulated during extended academic residences in Fujian and Jiangsu to demonstrate how “politics” has sustained cultural production from 1949 onward. Indeed, one key argument is that politicization of the cultural realm has created an immense community of artists whose livelihoods are now threatened by Dengist economic reforms. Another is that state institutions continue to shape artistry in ways unappreciated by most Western observers.”

“In its conception, The Party and the Arty is concerned with artists' evolving relationships to two massive and intertwined structures — the cultural bureaucracy and the cultural marketplace...His methodological focus is on institutions of patronage; that is, the state and non-state forces that define, disseminate, and compensate creative labor... While some artists may buck the system, many are, unsurprisingly, deeply involved in personal quests for social status. Kraus argues that although intellectual suffering was undeniably a consequence of Maoist populism and paranoia, state patronage of the arts was far more widespread than under Deng. Forced to turn to the marketplace for economic support, post-Mao artists are thus far more likely to turn their talents to other pursuits, which may also be inimical to state orthodoxy. The result is a fundamental transformation of China's political system. Once “possessing an important dimension that is essentially aesthetic” (p. 4), state power must now compete for cultural hegemony with the very commercial forces its reforms have unleashed.”

“Normalizing Nudity” (Ch. 3) provides an important case study of post-Maoist ambiguity in the regulations governing individual self-expression. By tracking state responses to nude art and depictions of nude human figures, Kraus argues that local responses to national campaigns betray a perfunctory conformism first observed by Daniel C. Lynch in After the Propaganda State (1999). Reassertion of patriarchy has accompanied the gradual creep of a “bread and circus public culture” (p. 98), with the state allowing artists and intellectuals to satisfy their erotic interests in exchange for political quiescence. “The Chinese Censorship Game: New Rules for the Prevention of Art” (Ch. 4) advances Kraus' claim that markets have further encouraged this moderate risqué sensibility by reducing the penalties for sexual or obliquely transgressive references.

“Kraus rejects what he calls the “Godzilla model” of the Chinese arts scene, which portrays artists as free-spirited idealists and state power as brutally malevolent. Instead, he suggests that both sides are motivated by the pursuit of professional and economic security. “Artists as Professionals” (Ch. 5) and “The Price of Beauty” (Ch. 6) address these two themes in full. How have artists attempted to maintain their institutional privileges in the post-Mao era? How do they make money? In answer to both questions, Kraus suggests that researchers must begin from the premise that Chinese artists, taken as a class, have few inherent qualms about mixing art with politics. Market and media change, however, have created a climate in which “all artists feel they must often hustle in ways that are corrosive and demeaning of their artistic integrity.”

“Although income data is sketchy, Kraus seems to be suggesting that economic inequalities are a far more galling reality under Deng than under Mao. Certainly anecdotal evidence and slashed budgets for state cultural institutions suggest as much. Yet if Kraus' analysis belies nostalgia for any particular period, it is (p. 195). The perception of China's arts scene as impoverished by the growing cultural marketplace is a familiar one.”

Book: “The Party and the Arty in China: The New Politics of Culture“ By Richard Curt Kraus (Rowman and Littlefield, 2004).

Propaganda in China

Control of the media and culture is essential for leaders to get their message and agendas across. Mao Zedong once said that control of information and control of the gun are the two pillars of Communist Party power.In the old days, Communist propaganda had a strong influence on the masses. A single word or phrase from Mao Zedong could mobilize millions. These days propaganda is largely greeted with a shrug. Few people tale it seriously anymore. Even so political satire in China is largely absent. China doesn’t even allow cartoons of its leaders.

The Propaganda Department is now known as the Publicity Department. New policies are still sometimes introduced with old fashioned Communist marketing. Jiang Zemin’s “Three Represents” policy was inaugurated with a play called the "Vanguard of an Era," featuring the stories of six heroes that personify the virtues of the theory. After seeing it a member of a selected audience told the People Daily “an audience of hundreds felt their souls fiercely shaken, and or eyes flowed with tears." The Propaganda Department is headed by the Central Leading Group on Propaganda and Ideological Work, whose leader is often a member of the powerful Standing Committee of the Politburo and whose deputy leader is a member of the Politburo. The new The Propaganda Department headquarters is located next to the Zhongnanhai leadership compound.

Rana Foroohar wrote in Time: When leaders begin blaming "international hostile forces" for problems at home, it's a sure sign they've got trouble. That's exactly what Chinese President Hu Jintao did recently in a speech, published by a Communist Party magazine, in which he accused outsiders of plotting to "westernize and divide China." The hard-line rhetoric is likely aimed at diverting attention from a growing list of internal issues, including income inequality, unemployment and discontent over blatant land and money grabs by self-dealing state officials and developers. [Source: Rana Foroohar, Time, January 16, 2012]

See Separate Article PROPAGANDA IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Bo Xilai's ”Red Culture” Revival

Bo Xilai, the disgraced Communist Party leader imprisoned in 2013, gained notoriety for a citywide campaign in Chongqing to revive Mao-era communist songs and stories, dredging up memories of the chaotic Cultural Revolution, although Bo claimed he wasn't motivated by politics and only wanted to boost civic pride. The campaign fizzled after initial bursts of positive publicity.

Reporting from Chongqing before the approach of the 90th anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party of China in July 2011, Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “The country is being swept up in a wave of orchestrated revolutionary nostalgia...The local satellite television station recently stopped broadcasting sitcoms and now shows only “revolutionary” programs and news. Government workers and students have been told to spend time working in the countryside. The local propaganda department launched a “red Twitter” micro-blogging site, blasting out short patriotic slogans. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, June 29. 2011]

And in what seems like a throwback to the days of the Cultural Revolution, residents have been encouraged—or told—to read revolutionary books and poetry and to gather regularly in parks to sing old songs extolling the Communist revolution. A recent Sunday gathering, including a colorful, choreographed stage pageant, attracted an estimated 10,000 flag-waving people, many in uniforms and red caps and mostly organized by the party chiefs in their schools and factories.

See Separate Article MAO AND CULTURAL REVOLUTION NOSTALGIA AND KITSCH factsanddetails.com

Crackdowns on the Arts Under Xi Jinping

The Chinese government asserted its control over the arts in 2013 after Xi Jinping took power. Leo Lewis wrote in The Times: “Draconian curbs on song, dance and variety extravaganzas has put more than 10,000 Chinese impresarios out of business, bludgeoned the music industry and destroyed a gala performance market worth $15 billion. The crunch, imposed by Beijing, has left the entertainment industry in tatters and threatens thousands of stage careers as local governments turn to cheap alternatives. State-organised events such as the opening of a new shopping centre, which once lured stars of television and film with hefty appearance fees, are now forced to make do with anaemic performances by local students. One talent agent said that even A-list celebrities were suffering. Scores of shows have been abruptly cancelled. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, October 31 2013]

Hannah Beech wrote in Time, “China’s journalists are subject to intense censorship, with editors receiving daily directives on what topics have been deemed taboo. Self-censorship is rampant. While a few enterprising newspapers gained fame for their muckraking after the turn of the century, their exposés have waned in recent years, as liberal editors have been sacked and investigative reporters punished. In 2015, China had the largest number of journalists behind bars of any nation, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. Several imprisoned reporters have been paraded on state TV to confess to their purported crimes. [Source: Hannah Beech, Time, February 19, 2016 ++]

Geremie R. Barmé is a professor of Chinese history at the Australian National University, told the New York Times: “There is no doubt that the threnody of the era of “Big Daddy Xi,” as the official media call” Xi Jinping, “is boredom. The lugubrious propaganda chief, Liu Yunshan, the Internet killjoy Lu Wei and Xi himself have together cast a pall over Chinese cultural and intellectual life. At the same time, the party-state is at pains to extol homegrown innovation and creativity. ..Perhaps one of the challenges China poses to our understanding of narratives of development, progress and modernity is that innovative change may well also be possible, if not flourish, under postmodern authoritarianism. Or does one just pickpocket innovation from elsewhere and use state-controlled hyperbole to lay claim to creativity?

See Separate Articles: XI JINPING, THE MEDIA AND THE MEDIA’S PORTRAYAL OF HIM factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REFORM AND CRACKDOWNS ON INTELLECTUALS AND WRITERS IN CHINAfactsanddetails.com

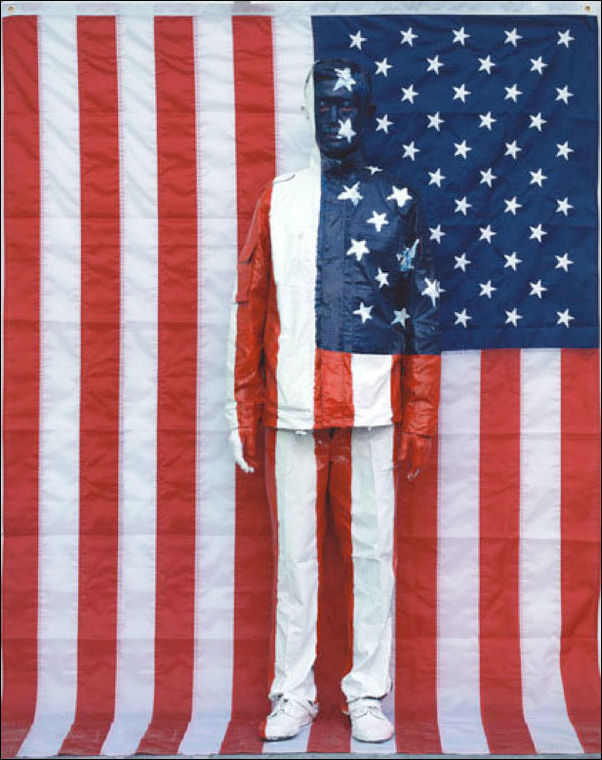

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

China’s Cultural Expansion Abroad

Beijing has created almost 300 Confucius institutes around the world, teaching Chinese language and culture, and spent a reported £4bn on expanding state media. It has created a new English language newspaper, Russian and Arabic TV channels and a 24-hour English news station run by the Xinhua state news agency. In a sign of how far the Chinese media reaches, you can buy the European edition of the English-language China Daily in a Sheffield and read Xinhua's Kenyan "mobile newspaper" on your phone in Nairobi. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, December 8, 2011]

In Boston, China Radio International has claimed the frequency previously owned by WILD-AM "home for classic soul and R&B" to the surprise of listeners. Beijing has also attempted to harness the credibility of established western media, distributing 2.5m copies of China Daily's China Watch supplement in the Washington Post, New York Times, and Daily Telegraph.

Francesco Sisci wrote in Asian Times , “In more than one way, the success of communism in China also derived from the uncritical arrival of Western culture. Many Chinese intellectuals saw communism as the most advanced form of Westernization, and thus China, wishing to catch up with the West, took on the most advanced stage of the culture, skipping other “lesser systems”. It is clear now, after decades of contact with Western culture, that this perception was faulty, and it has caused huge trouble in China.” [Source: Francesco Sisci, Asian Times, April 1, 2010]

"So in pursuit of “Western cultural models”, China ran like a bulldozer over its culture and its tradition. However, traditions, part of a child's upbringing, are hard to suppress and eliminate. When officially quashed in one area, they reappear elsewhere, possibly in the most backward and conservative form. During the 1960s and the Cultural Revolution, inspired by foreign thinkers like Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong's Red Guards took revenge on anything foreign: Western music, Western paintings and contacts with “foreign spies” along with destroying “relics” of China's past. The two went hand-in-hand.”

Image Sources: 1, 2 and 4) University of Washington; 3) Ohio State University ; 5) Poster, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; Wiki Commons, Red Detachment by Asia Obscura; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com ; Asia Weekly (Han Han)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021