CHINESE CULTURE

Palace concert in the Song era The culture of China is very interesting because it involves so many people that are surprisingly diverse on individual, regional and socio-economic levels and even though China has history and traditions that go back 5,000 years thing have changed quite drastically and dramatically in the last 75 years and the pace and extensiveness of those changes continues today.

There is a long tradition of imperial patronage of the arts that continues today in the form of state-funded literary guilds that pay writers for their work. The Chinese arts have traditionally been linked with scholarship. In imperial China, courtiers and scholars were supposed to be skilled in poetry, music, calligraphy, and painting as well as literature and philosophy. Chinese artists and poets were mostly amateurs who made their living doing something else, namely working in the civil service.

Serenity and tranquil beauty have traditionally been valued in Chinese culture and aesthetics. Fei Bo, a Chinese choreographer, told The Times: “Our culture is more about spiritual things, and nature is much more important to us. In our traditional painting the strokes are very simple but they leave a big space for your imagination.” Unfortunately many works that illustrated these virtues have been lost. Chinese emperors had the habit of destroying the art and literature created by their predecessors. During the Cultural Revolution, the Communists continued this tradition by destroying much of what was left from an Imperial Age that had lasted for thousands of years.

Thousands of years ago, Chinese intellectuals were already essential figures in assisting their emperors in multiple ways, including providing policy suggestions as well as educating the general public. Shanghai was the undisputed capital of Chinese culture before World War II. After the Communists came to power in 1949 there wasn’t much culture. After things started loosening up after the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s the center of Chinese culture shifted to Beijing.

The entertainment industry in China is big and profitable. It was projected to generate revenues of around $358.6 billion in 2021, according to a report by consultancy PwC.

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; INTELLECTUALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CULTURE UNDER THE COMMUNISTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CENSORSHIP IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CULTURAL REFORM IN CHINA AND CRACKDOWNS UNDER XI XINPING factsanddetails.com ; ART AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com; MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com; FILM AND ACTORS factsanddetails.com; TELEVISION AND MEDIA factsanddetails.com; INTERNET AND COMMUNICATIONS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Chinese Culture: China Culture.org chinaculture.org ; China Culture Online chinesecultureonline.com ;Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Transnational China Culture Project ruf.rice.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Cambridge Companion to Modern Chinese Culture Amazon.com; “Encountering the Chinese: A Modern Country, an Ancient Culture” by Hu Wenzhong, Cornelius N. Grove , et al. Amazon.com; Hawai’i Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture,” translated by Stephen West, edited by Victor H. Mair, Nancy S. Steinhardt, and Paul R. Goldin Amazon.com; “Faces of Tradition in Chinese Performing Arts” by Levi S. Gibbs Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Conference on Literature and Art”: A Translation of the 1943 Text with Commentary” (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies) by Bonnie S. McDougall and Zedong Mao Amazon.com; Also See Talks At The Yenan Forum On Literature And Art in “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 4" (1941-1945) Amazon.com; “The Party and the Arty in China: The New Politics of Culture” by Richard Curt Kraus Amazon.com; “It's All Chinese To Me: An Overview of Culture & Etiquette in China” by Pierre Ostrowski Matthew B. Christensen, Gwen Penner (Illustrator) Amazon.com; “China A to Z: Everything You Need to Know to Understand Chinese Customs and Culture by May-lee Chai and Winberg Chai Amazon.com

Museum, Libraries and Cultural Entrepreneurs in China

According to Statista there were 5,132 museums in China in 2019. According to Wikipedia there were 3,589 museums in China, including 3,054 state-owned museums (museums run by national and local government or universities) and 535 private museums in 2013. These museums have a total collection of over 20 million items and held more than 8,000 exhibitions with 160 million people visits each year in the early 2010s. Most of the museums are cultural or historical.

The National Library in Beijing (founded in 1909) is the largest in China, with over 22 million volumes, including more than 291,000 rare ancient Chinese books and manuscripts. The Chinese Academy of Sciences Central Library, in Beijing, has a collection of 6.2 million volumes, with branches in Shanghai, Lanzhou, Wuhan, and Chengdu. The Capital Library in Beijing (2.6 million volumes) is the city's public library. “Small lending libraries and reading rooms can be found in factories, offices, and rural townships. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Groundbreaking 20th century Chinese cultural entrepreneurs included Lü Bicheng, a famous classical poet, who parlayed her literary prestige into a career as the principal of a Beijing girls’ school and then used her business fortune to build a high-profile persona as a glamorous foreign correspondent; Aw Boon Haw, the "tiger" behind the Tiger Brand pharmaceutical company; and the Shaw Brothers, ethnic Chinese filmmakers and exhibitors who drew thousands of people out each night to watch movies in Singapore and British Malaya. [Source: Book: “The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia, 1900-65", edited by Christopher Rea and Nicolai Volland (Vancouver: University of British Columbia, Press, 2015)]

Culture in Modern China

The message these days seems to be that you can have punk rock, sex radio and shock art as long as it doesn’t threaten the Communist dictatorship. Even so many writers and artists have made a name for themselves outside of Asia. They find the intellectual atmosphere at home which emphasizes hierarchy and seniority oppressive.

On one hand the Chinese system supports schools that produce dancers, singers, actors and performers at rate much higher than almost country on earth. But on the other hand it stifles creativity and innovation in the way it attempts to control everything. One modern dancer told the New York Times, "The speed at which culture has developed has no comparison to the economy. We have a very rich culture full of artists, but we don't have art. Propaganda and politics have messed everything up."

Spending in the arts — which includes performing arts, sports, film television and radio — has increased from $3.6 billion in 2000 to $6 billion in 2005 but much of money has gone into building projects like National Grand Theater in Beijing which cost $365 million and other showcase theaters, concert halls, museums and other culture facilities, leaving relatively little money for cultural groups such as theater groups, orchestras and artist unions whose funding in many cases has been cut.

State-owned dance and theater companies, musical and theatrical groups and even military dance ensembles have been encouraged or become financially independent and create shows that can make money abroad.

People in China are used to going out and eat at night. They’re not used to going out to the theater and buy tickets. For many decades, tickets had been given away by employers or other sources. Changing this expectation of free tickets has been one of the great challenges in the development of the live performance market in China, performing arts promoters have said. [Source:Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, July 9, 2010]

“Many cities in China have built a top-notch performing arts centers in the hopes of lifting its cultural credentials and offering new forms of live entertainment to the increasing numbers of middle-class and wealthy Chinese. Yet many arts professionals from the West say China has a long way to go. Audiences remain small. Many of those who attend are not accustomed to paying for tickets. And after years of state-financed performances, the government is increasingly looking to the private sector to support both foreign and domestic arts troupes.”

Cultural groups often don’t have a clue on how to market themselves or raise funds. Some in the field have attended seminars at the Kennedy Center in Washington on how to pursue donors and sustain ticket sales. Much of the money that cultural groups do get from the government is in the form of loans that are tied to producing works that audiences will want to come and see.

Modern Cultural Scene in China

Han Han, a popular writer

and cultural figure

China’s intellectual scene is now among the most vibrant in the world, bringing together competing ideas both foreign and domestic, and producing thought-provoking works of literature, memorable films, edgy works of modern art and a lively indie music scene. Culture and art are now big business in China too. David Barboza wrote in the New York Times, “China’s Cultural landscape is now filled with big-budget historical dramas, multimillion dollar art auctions, government-backed opera and dance extravaganzas and bold new state-financed entertainment venues that suggest a melding of art, culture and power and national pride.” The entertainment industry in China is big and profitable. It was projected to generate revenues of around $358.6 billion in 2021, according to a report by consultancy PwC.

Zhang Xianmin, Professor of Beijing Film Academy, wrote: “Cultural resources are clustered in big cities; the rest of China are cultural deserts... On the one hand, the cultural development of China lags behind its economic development because the former developed under various kinds of restraints and unhealthy favoritism. On the other, Chinese culture does not have any real power in society; what it has are money-making industries and politically driven propaganda (in the name of spiritual development). The differences between China and other culturally more developed countries are both the lack of investment by big corporations and the lack of tax incentives for individual cultural workers.” [Source: Zhang Xianmin, translated by Isabella Tianzi Cai, dGenerate films, September 29, 2010]

There are many difficult-to-fathom aspects of modern Chinese culture. Today kitsch and cute arguably hold a higher place in hearts of Chinese than traditional fine arts. Silly television game shows, NBA basketball, pictures of kittens playing with balls of yarn and sentimental ballad music seem to be more popular than Peking Opera, silk scroll paintings or traditional erhu music.Evan Osnos wrote in New York Times: “The defining fact of China in our time is its contradictions: The world’s largest buyer of BMW, Jaguar and Land Rover vehicles is ruled by a Communist Party that has tried to banish the word “luxury” from advertisements. It is home to two of the world’s most highly valued Internet companies (Tencent and Baidu), as well as history’s most sophisticated effort to censor human expression. China is both the world’s newest superpower and its largest authoritarian state. [Source: Evan Osnos, New York Times, May 2, 2014]

IP was a film, fiction and culture industry buzzword in 2015. According to China Film Insider: “In China, the abbreviation IP stands for more than intellectual property: it refers to stories with an existing audience that will follow as they are retold across different media platforms. Online fiction has become a key source of IP and new film scripts, leading an executive from one new studio to suggest a diminished role for traditional screenwriters in the filmmaking process, a call that sparked an outcry in the ranks of beleaguered writers. [Source: Jonathan Landreth, Sky Canaves, Pang-chieh Ho, and Jonathan Papish, China Film Insider, December 31, 2015]

Han Culture

The Han Chinese are the predominate ethnic group of China. They make up more than 90 percent of the population of China. Chinese culture is effectively the culture of the Han Chinese. The Chinese government counts 55 other ethnic groups, including Tibetans and Uygurs, which make their own cultural inputs to China but these are often not viewed as Chinese culture.

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: “The variety of traditional Han musical instruments is sufficient to form an orchestra. Three of the most popular instruments are the two-string violin (erhu), the lute (zheng), and the pipa. There are also many percussion instruments, including gu (drums), ban (clappers), muyu (a wooden "fish" played by striking with a stick), xiao luo (gong), and bo (cymbals). Institutions of traditional music and dance were established early in the 1950s. [Source:C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *\; Stevan Harrell, “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures”, Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

“The ancient literature of the Han, including poems, drama and novels, history, philosophy, and rituals, is a great world treasure. Many works have been translated into other languages and introduced into many countries. The great poets Li Bai and Du Fu, who flourished in the golden age of Chinese poetry (Tang Dynasty, 618 — 907), have produced works that belong to world literature. The monumental Chinese novels, starting in the 14th century with the epic “Water Margin”, also include “Journey to the West”, “Golden Lotus”, and “Dream of the Red Chamber”. One should also mention philosophical masterpieces written around the 5th century BC, namely Confucius' Analects and Lao-zi's The Way and Its Power. *\

“The Han have also contributed greatly to world civilization by inventing paper (2nd century BC), ceramics (7th century), gunpowder (10th century), porcelain (11th century), movable printing (11th century), and the compass (12th century). *\

Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and Culture in China

Confucianism, Taoism (Daoism) and Buddhism are the the three main pillars of historic Chinese thought. Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner wrote in “CultureShock! China”: Much of Chinese tradition and culture is shaped by the influence of these three philosophies., from the way a child cares for his or her parents, to how to approach one’s career. In the past 50 years, Communism has overlaid another set of attitudes, beliefs and actions over these traditions, adding a discipline and focus that has allowed China to quickly reshape itself into a force in the modern world. The older generation of Chinese are usually religious and strongly adhere to the customs and beliefs of their religion. But China is also undergoing a rebirth of interest in religion that is occuring at all levels of society and among all age groups. [Source: “CultureShock! China: A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette” by Angie Eagan and Rebecca Weiner, Marshall Cavendish 2011]

Confucius (551–479 BC) was a thinker, political figure, educator and founder of Confucian School of Chinese thought. His teachings, preserved in the Analects, form the foundation of much of subsequent Chinese speculation on the education and comportment of the ideal man, how such an individual should live his life and interact with others, and the forms of society and government in which he should participate. Quick dips into the Analects gives us four themes that we see carried into modern Chinese society. The first concerns the proper way a person should behave. The Analects says, ‘The gentleman concerns himself with the way; he does not worry about his salary. Hunger may be found in plowing; wealth may be found in studying.’ He emphasises sincerity and honesty. He has no friends who are not his equals. If he finds a fault in himself, he does not shirk from reforming himself.’ The second speaks of humanity. Confucius said, ‘If an individual can practice five things anywhere in the world, he is a man of humanity.’ These things are ‘reverence, generosity, truthfulness, diligence and kindness’. ‘If a person acts with reverence, he will not be insulted. The third is of filial piety — respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors and the code of conduct that goes along with that. The final main theme of Confucius’ teachings has to do with governing. Confucius suggests that virtue in government will bring out the best in people. He said, ‘Lead them by means of government policies and regulate them through punishments, and the people will be evasive and have no sense of shame. Lead them by means of virtue and regulate them through rituals and they will have a sense of shame and moreover have standards.’

Daoism (Taoism) The core concept of Daoism is dao, which means the Way. The Way is the order of things, the path of life, the life force, the driving power in nature, the harmony of the universe, and the eternal spirit which cannot be exhausted. Daoism is said to have originated with Laozi, the old philosopher. There are five main ethical concepts put forward by Daoism. The first is dao, the way. The second is de, which can be described as the power or virtue to transform something. A common example would be the ability of an actor to bring a story to life through a character. The third is ming, which means name. What something is called is as important as what it is not called — it is defining the reality of something. The fourth is chang, or what is eternal and true, regardless of situation. For example, something that should be applied equally to all people of all cultures, times and levels of social development. The fourth is wei or wu-wei, intended or nonintended action. The fifth is pu, purity. One of the most dramatic ways that Daoism continues to influence modern life in China is through the belief in qi. Pronounced ‘chee’, this is the Chinese term for vital energy or life force. It is a core concept in traditional Chinese medicine, as well as in some forms of Chinese martial arts. For example, the popular form of excercise, tai chi, originates from this concept.

Buddhism is China’s main religion and many Chinese have a great respect for the Buddhist monks and the lifestyle that they lead. It is a non-native religion that arrived in China around the A.D. first century and has contributed greatly to Chinese culture since. The art and writings of Buddhism can still be observed at Mogao Caves, Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Caves. At about this time, Bodhidharma, the originator of Zen Buddhism, spent time in the Shaolin Temple, famous in modern time for its fighting monks. Many of the temples, pagodas and sacred mountains that can be visited across China trace their origin to this time. Buddhism permeated through daily life and had a profound impact on architecture, painting, sculpture, music and literature. It also is the root of many colloquial phrases and parables.

See Separate Articles: BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; LOTUS SUTRA AND THE DEFENSE OF BUDDHISM AGAINST CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; RELIGIOUS TAOISM, TEMPLES AND ART factsanddetails.com; TAOISM, IMMORTALITY AND ALCHEMY factsanddetails.com

Nature in Chinese Culture

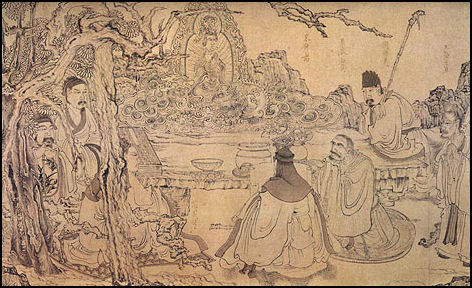

Gathering of poets and scholars According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In no other cultural tradition has nature played a more important role in the arts than in that of China. Since China's earliest dynastic period, real and imagined creatures of the earth—serpents, bovines, cicadas, and dragons—were endowed with special attributes, as revealed by their depiction on ritual bronze vessels. In the Chinese imagination, mountains were also imbued since ancient times with sacred power as manifestations of nature's vital energy (qi). They not only attracted the rain clouds that watered the farmer's crops, they also concealed medicinal herbs, magical fruits, and alchemical minerals that held the promise of longevity. Mountains pierced by caves and grottoes were viewed as gateways to other realms—"cave heavens" (dongtian) leading to Daoist paradises where aging is arrested and inhabitants live in harmony. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“From the early centuries of the Common Era, men wandered in the mountains not only in quest of immortality but to purify the spirit and find renewal. Daoist and Buddhist holy men gravitated to sacred mountains to build meditation huts and establish temples. They were followed by pilgrims, travelers, and sightseers: poets who celebrated nature's beauty, city dwellers who built country estates to escape the dust and pestilence of crowded urban centers, and, during periods of political turmoil, officials and courtiers who retreated to the mountains as places of refuge.\^/

“Early Chinese philosophical and historical texts contain sophisticated conceptions of the nature of the cosmos. These ideas predate the formal development of the native belief systems of Daoism and Confucianism, and, as part of the foundation of Chinese culture, they were incorporated into the fundamental tenets of these two philosophies. Similarly, these ideas strongly influenced Buddhism when it arrived in China around the first century A.D. Therefore, the ideas about nature described below, as well as their manifestation in Chinese gardens, are consistent with all three belief systems.\^/

“The natural world has long been conceived in Chinese thought as a self-generating, complex arrangement of elements that are continuously changing and interacting. Uniting these disparate elements is the Dao, or the Way. Dao is the dominant principle by which all things exist, but it is not understood as a causal or governing force. Chinese philosophy tends to focus on the relationships between the various elements in nature rather than on what makes or controls them. According to Daoist beliefs, man is a crucial component of the natural world and is advised to follow the flow of nature's rhythms. Daoism also teaches that people should maintain a close relationship with nature for optimal moral and physical health.\^/

“Within this structure, each part of the universe is made up of complementary aspects known as yin and yang. Yin, which can be described as passive, dark, secretive, negative, weak, feminine, and cool, and yang, which is active, bright, revealed, positive, masculine, and hot, constantly interact and shift from one extreme to the other, giving rise to the rhythm of nature and unending change.\^/

“As early as the Han dynasty, mountains figured prominently in the arts. Han incense burners typically resemble mountain peaks, with perforations concealed amid the clefts to emit incense, like grottoes disgorging magical vapors. Han mirrors are often decorated with either a diagram of the cosmos featuring a large central boss that recalls Mount Kunlun, the mythical abode of the Queen Mother of the West and the axis of the cosmos, or an image of the Queen Mother of the West enthroned on a mountain. While they never lost their cosmic symbolism or association with paradises inhabited by numinous beings, mountains gradually became a more familiar part of the scenery in depictions of hunting parks, ritual processions, temples, palaces, and gardens. By the late Tang dynasty, landscape painting had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. The prominence of landscape imagery in Chinese art has continued for more than a millennium and still inspires contemporary artists.” \^/

Culture, Confucianism and Politics

Culture and politics in China have traditionally been closely associated with one another in China. As far back as the 6th century B.C., Confucius said that music and dance were such important elements of political life they should not be squandered on entertainment. According to one story, Confucius found himself at a festival with singers and jesters and declared, "Commoners who beguile their lords deserve to die. Let them be punished!" The party was immediately stopped and the performers were killed.

In the Ming dynasty the only forms of entertainment that were tolerated were those about "righteous men and chaste women, filial sons and obedient grandsons, and those who encourage the people to do good." The Yongle emperor declared that anyone found with banned works "should be killed, together with their entire families." The Qianlong Emperor continued this tradition in the Qing Dynasty. He collected 1,000 dramas and novels from around the country and then banned or censored the one he deemed to be morally or politically unfit.

“Yiyin”, or “lingering sound,” is an important concept not only in music but in all the Chinese arts. It was described in Confucius-era “The Book of Rites” as one string plucked on the zither “and three others will reverberate so there is lingering sound.”

Into the 20th century, drama and the arts were judged by Confucian values. Performers were regarded as the scum of the earth and even bought and sold like slaves. Reformers and Communists associated these ideas with backwardness and feudalism and elevated the status of performers.

Emperor Qin and the Burning of Books and Burying of the Scholars

One rendering of Emperor Qin Shihuang Qin Shi Huang (ruled 221–210 B.C.), whose tomb with an army of lifelike terra-cotta soldiers is a big tourist attraction in Xian, China, was the great unifier of China and its first emperor. He launched the Great Wall of China, ended the rule of feudal states and organized China into a system of prefectures and counties under central control but also oversaw the notorious “burning of the books” and “brying of the Confucian scholars.”

Emperor Qin ordered all books burned except those that praised the emperors (one reason why historical records before the Qin Dynasty are scarce). Among the primary targets of this order were all books associated with the Confucians, several hundred of which were reportedly buried alive. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: Among the most infamous acts of the First Exalted Emperor of the Qin were the “burning of books,” ordered in 213 B.C., and the “execution of scholars,” ordered in 212 B.C. The execution of some 460 scholars was an attempt to eliminate opposition to the emperor by ruthlessly destroying all potentially “subversive” elements in his entourage. The two measures taken together suggest something of the habit of mind of the First Emperor, as he was influenced by advisers like Li Si but, again, it is significant that the following document comes down to us from the ensuing Han period.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The “burning of books,” ordered in 213 B.C., was an effort to achieve thought control through destroying all literature except the Classic of Changes, the royal archives of the Qin house, and books on technical subjects, such as medicine, agriculture, and forestry. The measure was aimed particularly at the Classic of Documents and the Classic of Odes. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

See Separate Article EMPEROR QIN SHI HUANG’S RULE (221-206 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Museum Boom in China

Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times in 2013: China is opening museums on a surreal scale. Museums — big, small, government-backed, privately bankrolled — are opening like mad. In 2011 alone, some 390 new ones appeared. And the numbers are holding. Many are multipurpose affairs, mixing history, ethnography, science, politics, art and entertainment. The museum devoted only to art is a relatively novel concept in China. Models for it, most of them Western, are still being sorted out, though they tend to line up at either end of the temporal spectrum, focusing on the very new or the very old.[Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, March 20, 2013]

“Until recently, museums of contemporary art in China had been privately run, either as corporate entities or as the vanity showcases of rich collectors. Last October, an important precedent was set with the opening of the Shanghai Contemporary Art Museum, the country’s first government-supported museum of up-to-the-minute work.

“If official acknowledgment of the importance of Chinese art’s international stature was long delayed, it was fairly bold when it arrived. The Shanghai museum, popularly known as the Power Station of Art — it’s in a converted 19th-century power plant — is physically spectacular. It opened with a major globalist bang in the form of the 9th Shanghai Biennale, which filled the capacious interior and spread out into the surrounding city.

“The Biennale still has a little time to run; it closes March 31. Meanwhile, some 1,600 miles west of Shanghai, at the oasis city of Dunhuang on the edge of the Gobi Desert, another museum, or something like a museum, far less conventional than the Power Station, is under construction. Its purpose is not to attract crowds to new art, but to keep them away from damaging contact with old art, specifically the ancient and rapidly deteriorating Buddhist murals that cover the interiors of hundreds of caves in the Dunhuang area. Painted between the fourth and 14th centuries at a central point on the Silk Road, the caves constitute a virtual museum of cosmopolitan Chinese culture spanning a millennium.

“As different as they are, the Shanghai and Dunhuang museums share one quality typical of China’s new cultural institutions: ambitiousness. Often this is simply measured in size. When the revamped National Museum of China opened in Beijing in 2011, much was made, officially, of its being, square foot for square foot, the single largest museum of any kind in the world, even though the history of China it told was strategically truncated.

Western Culture in China

These days, young Chinese are more interested in money, motorcycles, fashion, sex, rock music, pop art, the NBA, hip hop, karaoke bars, runway models, and black leather miniskirts than either Confucianism or Communism. In Shanghai you can find Wild West bars with waitresses in cowboy outfits and Filipino bands covering Kenny Rogers tunes. At the Golden Age Club half-naked Russian dancers entertain guest while waiters in tuxedos serve them $2,300 bottles of Remy Martin Louis XVII in $1,000-a-night private rooms.

Referring to the introduction of Western culture, Deng once said "when you open the window, flies and mosquitoes come in." Ads for Japanese cars and detergent have been placed over Mao slogans; worker's union halls that once showed anti-imperialist propaganda films now show Rambo movies and sponsor aerobics and ballroom dancing classes; and more people read body building magazines and movie tabloids like World Screen than the Little Red Book.

Attitudes toward Western culture rise and fall. Chinese government allowed the pop groups Wham and Jan and Dean to perform in the 1980s but later closed down discos as a form of "spiritual decay." In 1994 the government allowed the showing of current foreign films but after “The Fugitive”, with Harrison Ford, played to packed movie houses, the Propaganda Department closed down the film and condemned the circulation of “decadent music and films."

Upset by the dominance of Japanese and Disney characters on television and in comic books, one commentator wrote in the Worker's Daily in 1996, "People cannot but worry about the 'malnutrition' resulting from 'children's one-sided diet' of cultural goods: Watching cartoons has become the most important entertainment for children, but the contents are almost all foreign, which includes monsters, devils and sorcerers." In the popular book “China Can Say No”, the authors suggested that Hollywood be burned and advised Chinese not to fly Boeing 777 planes.

Westernization, its critics claim, promotes too much individualism and has broken down bonds that unite Chinese.

Foreign Performing Artists in China

Foreigners in the performing arts are increasingly making their presence known in China. On its opening night in May 2010, the Guangzhou Opera House featured Puccini’s Turandot, directed by the Chinese filmmaker Chen Kaige, with Lorin Maazel conducting. The Swedish soprano Irene Theorin and the Canadian tenor Richard Margison sang the lead roles. The Opera House, designed by Zaha Hadid, then was host to Ballet Preljocaj, a French dance company performing the contemporary Snow White with costumes by Jean-Paul Gaultier. That was followed with a concert by Michael Bolton, the American soft-rock singer.[Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, July 9, 2010]

“Tracking the number of foreign performing arts troupes that visit China is difficult. According to data from the Ministry of Culture, the number of state-sponsored cultural exchanges seems to be declining; China’s government invited 44 overseas artistic troupes to perform in 2009, half the number it sought in 2008. But 600 to 700 commercial performances from abroad were staged in 2009, a slight increase from 2008.”

“In June 2010, the China Arts and Entertainment Group and Littlestar Services — the London-based producer of the Abba-inspired musical Mamma Mia! — announced plans to produce a Mandarin-language version of the show. It is scheduled to open in Beijing next June, then travel to Shanghai and Guangzhou before touring elsewhere in Asia.”

“Promoters still think the Chinese business will probably take 10 years to be really significant because the audience that can afford tickets to such shows is still small. Average ticket prices have increased in recent years — seats for the 2006 Phantom in Shanghai averaged about 20 percent less than those on Broadway, but a similar show now would cost only 5 to 10 percent less than in New York.”

There are other obstacles to overcome. “Navigating the Chinese bureaucracy, including censors, and obtaining permits to put on shows can also be daunting for promoters. For instance, a planned production of The Vagina Monologues was scrapped in 2004 by wary officials, but the play made it to China in 2009.”

Some foreign promoters are finding it easier and quicker to make progress by forming joint venturers and managing Chinese entertainment companies. The Nederlander group formed a joint venture with Beijing Time New Century Entertainment in China in 2005 and has since produced four musicals in the country, including 42nd Street and Fame. It also entered into a joint venture with the Eastern Shanghai International Culture, Film and Television Group to manage and operate performance theaters in Shanghai.

UNESCO and Culture Grabs by China?

Acupuncture and Peking Opera are on the UNESCO intangible cultural heritage list. Chinese printing with wooden movable type, the technique for leak-proof partitions of Chinese junks and the Uyghur folk performance Meshrep were also on the intangible cultural heritage status and are in need of urgent safeguarding. Some take issue with other UNESCO intangible cultural heritage selections given to China.

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “In 2009 and 2010, more than a quarter of all items inscribed by Paris-based UNESCO on its cultural heritage roster were from China. Many of the items under China’s name are clearly Chinese, such as Peking Opera, acupuncture, dragon boat festivals and Chinese calligraphy. But also listed as Chinese are the epic of Manas, a poem that Kyrgyzstan considers the cornerstone of its national culture, as well as Tibetan Opera, and a Korean farmers dance. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, August 10, 2011]

Cecile Duvelle, head of UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage section, said in response to written questions by the Washington Post that a listing does not mean an item “belongs to the state” or that China’s cultural heritage “has more or less value,” but she added that the organization “is nevertheless discussing this unbalanced situation.”

Exactly which “practices, expressions, knowledge and skills” are put on UNESCO’s list gets decided by a U.N. committee made up of officials from 24 member states. And no country has been more active than China in nominating entries — to the chagrin of Mongolians, Kyrgyz, Tibetans and others whose culture is in part now registered as being from China.

When the United Nations first adopted a Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2003, the idea was to promote diversity and help indigenous peoples protect their heritage. Higgins wrote, ‘scholars with no dog in the fight also have been taken aback by a system they complain is driven by bureaucratic process and power politics as much as concerns for cultural authenticity.”

China’s Tries the Claim the Kyrgyz Epic Manas as Their Own

In 2018, the Poly Theater in Beijing hosted a stage version of "Manas" — the great Kyrgyz epic — that was seen by some as an effort by the Chinese to claim the story as their own, calling it one of China’s Three Great Oral Epics. Bruce Humes wrote in Altaic Storytelling: “A large-scale, colourful rendition of the Kyrgyz epic Manas was staged March 22-23 in Beijing’s ultra-modern Poly Theater. This performance came just two days after the newly anointed President Xi Jinping, speaking at the People’s Congress, cited two of the three great oral epics of non-Han peoples, Manas and the Tibetan-language King Gesar. While he mangled the title of the latter (Xi Jinpingian Sager), their mere mention shows their importance in the Party’s current multiethnic-is-good narrative. [Source: Bruce Humes, Altaic Storytelling, April 12, 2018]

“This centuries-old trilogy in verse recounts the exploits of the legendary hero Manas and his son and grandson in their struggle to resist external enemies — primarily the Oirat Mongols and the Khitan — and unite the Kyrgyz people. Along with heroic tales such as Dede Korkut and the Epic of Köroğlu, Manas is considered one of the great Turkic epic poems.

“Experts don’t agree on the epic’s history, but it has undoubtedly been around in oral form for at least several centuries. Composed in Kyrgyz, a language spoken by the Kyrgyz people in northwest Xinjiang and neighboring Kyrgyzstan, it was not available in full in Kyrgyz script until the mid-90s, and only then translated into Chinese. For details on the tribulations of the master manaschi, Jusup Mamay ( · ), who recited his 232,500-line version for prosperity (and was sentenced to a long stint of “reform through labor” during the Cultural Revolution for his efforts), see A Rehabilitated Rightist and his Turkic Epic.

“For some time now, scholars at the prestigious Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the state media have been busy “re-packaging” these three epics in a way that emphasizes their Chineseness, while playing down their non-Han origins. The trio, which includes the Mongolian epic Jangar, are now frequently referred to as “China’s three great oral epics” , despite the fact that all three were composed in languages other than Chinese by peoples (Kyrgyz, Mongols and Tibetans) in territories that were not then firmly within the Chinese empire.

“Media coverage of the Poly Theater production of Manas arguably takes this repurposing one step further. Entitled Manas Epic Reenacted on the Opera Stage , in the first two-thirds of the widely shared article, there are no mentions whatsoever of the word “Kyrgyz,” or references to the Kyrgyz people or language, or their homelands in Xinjiang or Kyrgyzstan. The opera, it reports, “recreates the magnificent, relentless struggle of the Chinese people for freedom and progress . . .”Granted, “Kyrgyz” does appear three times in the remaining third of the article, but it appears at the bottom in what is essentially a sidebar that describes the storyline of the opera; far from the eye-catching photos of the opera characters in exotic garb and the opening text that follows those colorful vignettes. Nowhere in the article is it noted that the epic was composed in a Turkic language (Kyrgyz) or that it is still considered by Kyrgyz speakers — on both sides of the border — to be the very incarnation of their identity as a nation.

Copyright Laws and Why There are So Bootleg and Download-for-Free Copies

The copyrights laws in China are weak and poorly enforced. Foreign companies want to see them shored up as a way of protecting their interests and combating counterfeiting and piracy As China has developed its own products and property — intellectual and otherwise — it is more interested in protecting them. In January 2007, in one of the first of ist kind, a Chinese newspaper — The Beijing News — sued an Internet site — Tom.cat — for copyright infringement.

Yu Hua, one of China’s most acclaimed writers, wrote: In 2005, “a friend of mine had a book published, only to find almost immediately that it could be downloaded free on the Internet. He pointed this out to the General Administration of Press and Publication, the government agency that regulates news organizations and publishing houses in China, and soon the agency wrote back, asking for the names of the bootleg providers. He supplied three Web addresses, but months later it was still possible to download his book on those same sites. Years passed, and nothing changed. [Source: Yu Hua New York Times, March 13, 2013]

“All my works — my novels, essays and stories — can be downloaded free. My most recent book, “China in Ten Words,” which cannot be published in mainland China because of the climate of censorship, was accessible online here as soon as it was released in Taiwan. Pirated hard copies of books circulate just as openly — my last novel, “Brothers,” had been on sale in bookstores for only a few days when a copycat edition appeared in sidewalk stalls outside my house.

“The power to enforce laws against theft of intellectual property rests with local culture and public security bureaus. But the culture bureaus’ inspection teams have a broad mandate, covering everything from Internet cafes and video-game emporiums to nightclubs and live arts performances; to them, pirated books are small potatoes. The public security bureaus, for their part, are too busy handling criminal cases and economic crimes to have time for pirated books. Sometimes we see these agencies join forces to smash book piracy rings, but that happens so infrequently that it has next to no effect on the problem.

“After China joined the World Trade Organization, in 2001, it began to crack down on commercial presses that printed pirated books. But the crackdown left an important loophole, as pirating simply gravitated to two locations particularly resistant to enforcement: prisons and former Communist base areas. Prisons, being under the purview of the judiciary, are exempt from the oversight of the culture bureaus’ inspectors. Even the public security bureaus cannot readily gain entrance. These presses, staffed by inmates who get only a small allowance for their labors, have become the most profitable in China.

“Old revolutionary base areas that were Communist Party strongholds before 1949, when the People’s Republic of China was founded, likewise enjoy a special status. They are typically in remote areas of poor provinces, like Shaanxi and Jiangxi. Several years ago, a publisher told me that he had traced pirated copies of his company’s books back to a plant in a former base area. Members of his staff, along with cultural inspectors and police officers, made a long journey to the plant, but soon found themselves outnumbered by local police officers. The top county administrator also arrived on the scene. “Have you no decency?” he asked them. The presses, he said, were a cash cow for the poverty-stricken region. The visitors were forced to retreat.

Han and Han on Why China Cannot Be a Cultural Power

Earlier in 2010, China's most famous blogger, Han Han, made a speech at Xiamen University discussing "why China cannot be a cultural power". The speech was an instant hit after being posted on Internet forums. "When our writers write, they are self-censoring themselves every second," he said. "How can any presentable works be created in such an environment? If you castrate all written works like you do with news reports, and then present them to foreigners hoping they will sell, do you think the foreigners are such morons?"

"The government wants China to become a great cultural nation, but our leaders are so uncultured," he told The New York Times. "If things continue like this, China will only be known for tea and pandas."

Echoing a similar sentiment, Julia Ju, who writes on mainland cultural affairs for several Hong Kong newspapers, said, "You can't have a cultural renaissance initiated by the state. Creativity is individual and basically the whole concept of a state-backed cultural revival is an oxymoron. If there are new and interesting things happening in China's culture, it is all due to individual efforts and not because of state policies."

Image Sources: 1, 2 and 4) University of Washington; 3) Ohio State University ; 5) Poster, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/ ; Wiki Commons, Red Detachment by Asia Obscura; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com ; Asia Weekly (Han Han)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021