YU HUA

Yu Hua is a popular Chinese writer who is known as both a literary master and dispenser of pulp schlock who has won commercial success by tossing out shocking and disgusting images and episodes. He has been praised by foreign critics and is frequently mentioned as a likely candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Yu is the author of “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant”, “To Live” and “Brothers.” Yu made his name in the late 1980s with a series of disturbing short stories. Since then he has written several novels and volumes of essays; and refined the art of circumventing censorship.

Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times in 2009, “Though nearly 50, Yu, who wears his hair short and spiky, looks relatively young. He speaks in emphatic bursts, his face often flushing red, and he is quick to laugh. It was, in fact, his boisterous laugh that almost got him into trouble on the morning of the solemn announcement of Mao’s death? He is a restless chain smoker, insists on ignoring China’s new ban on smoking in public places.[Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Yu has many critics. He has been accused of selling out to the very forces of commercialism and vulgarity anatomized in his novel; promoting a negative image of China and Chinese writers to the West; sinking into a world of filth, chaos, stench and blackness, without the slightest scrap of dignity; being a carpetbagging peasant who gives himself literary airs. One satire called Pulling Yu Hua’s Teeth compared his work with the pulling of four bad teeth — a black tooth, a yellow tooth, a falsetooth and a carious tooth, concluding that it’s “Not the Toothache but the Pain That Kills You.”

See Separate Articles: CULTURE AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; CONTEMPORARY CHINESE LITERATURE factsanddetails.com ; JIN YONG AND CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FICTION factsanddetails.com ; LITERATURE AND WRITERS DURING THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com ; ACCLAIMED MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MO YAN: CHINA'S NOBEL-PRIZE-WINNING AUTHOR factsanddetails.com LIAO YIWU factsanddetails.com ; YAN LIANKE factsanddetails.com ; WANG MENG factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR MODERN CHINESE WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR AND ACCLAIMED BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCIENCE FICTION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS factsanddetails.com ; MODERN POETRY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WRITERS OF CHINESE DESCENT: AMY TAM, HA JIN, YIYUN LI AND GAO XINGJIAN factsanddetails.com ; PUBLISHING TRENDS AND MODERN BOOK MARKET IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; INTERNET LITERATURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; POPULAR WESTERN BOOKS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN BOOKS ABOUT CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

Modern Chinese Writers and Literature: MCLC Resource Center mclc.osu.edu ; Modern Chinese literature in translation Paper Republic paper-republic.org

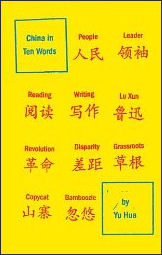

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND FILMS: “To Live” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese and with an afterword by Michael Berry (Anchor) Amazon.com; “To Live) (the Film Amazon.com; “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese and with an afterword by Andrew F. Jones (Anchor) Amazon.com; “Brothers” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese and with a preface by Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas (Anchor) Amazon.com; “The Past and the Punishments” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese and with a postscript by Andrew F. Jones (University of Hawaii Press) Amazon.com; “China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, translated from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr (Pantheon) Amazon.com; Yu Hua @ by Yu Hua digital book in Chinese published by Tianyi Yuedu Jidi and Hongqi Chubanshe;

Yu Hua’s Life

Yu was born in 1960 in Hangzhou in Zhejiang province, considered a breeding ground of many Chinese artists and intellectuals including Lu Xun, the pioneer of modern Chinese literature.His father was a doctor. Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times : Yu remembers him wearing a bloodstained smock in one small room and lived with his family across the road. Their home also faced a public toilet, where nurses often dumped tumors, and the local mortuary. On hot summer days, it was cool inside the mortuary, Yu recalled, and since the corpses were deposited only at night, I often took a nap there. Sleeping at night in our home, we would be woken by the sound of people crying.” [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009 ==]

When Yu was in his teens, the reading of novels was banned In China — especially foreign novels. But he and a friend managed to borrow a translation of Alexandre Dumas’s work, La Dame aux Camelias. They could have the book for only 24 hours. So they hastily copied out every word by hand. They worked all night long. But when they returned the novel, they were confused: Yu’s friend could not read Yu’s handwriting, nor could Yu read his friend’s. So, beneath a streetlamp they read aloud their copy of the book. With a sense of joy. They discovered a moment of liberation.

Shortly after the Cultural Revolution he was assigned to become a dentist. After peering into people’s mouths for five years, he decided to become a writer. “Yu never went to college. My entire education was encompassed by the Cultural Revolution, he said. I went to school in 1966 and came out in 1976, so I never received a proper education. Then, like many barefoot doctors in China in the late 1970s, Yu underwent only some very basic training before he became a dentist. He claims he became a writer because he hated his job: the inside of amouth is one of the ugliest spectacles in the world.” [Mishra, Op. Cit]

“In the early “80s he was living in a small town between Shanghai and Hangzhou. From his window he often observed workers of the local Cultural Bureau, the Chinese state’s salaried writers and artists, loafing in the streets. We were all very poor in those days, Yu recalled. The difference was that you could work hard to be poor as a dentist, or you could do nothing and still be poor as a worker in the Cultural Bureau. I decided I wanted to be as idle as the workers in the Cultural Bureau and become a writer.”

“Remarkably, Yu seems to have had as little apprenticeship in writing as he had in dentistry. Books were hard to come by during the Cultural Revolution, or they would circulate in mutilated form, like the torn copy of a novel by Guy de Maupassant, which Yu read the middle of (I remember it had a lot of sex, he said) without knowing its title or author. His formative reading experience was provided by the big character posters of the Cultural Revolution, in which people denounced their neighbors with violent inventiveness. I remember, Yu said, walking home from school and reading each poster as I walked along. I was not so much interested in the revolutionary slogans as in the stories.”

Yu Hua continues to live and work in China, operating in the hard-to-describe gray zone of an author who is not a dissident but sometimes writes things that deal with taboo subjects and hence can only appear in foreign editions. [Source: Jeffrey Wasserstrom, LA Review of Books, November 12, 2011]

Hu Yua During the Cultural Revolution

Hu Yua was six when the Cultural Revolution started and 16 when it ended. In “China in Ten Words”, he recounts some of his experiences during that time. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books:“Often the stories are less nostalgic than brutal. In the essay “Revolution,” he recounts how a friend’s father committed suicide after months of torture at the hands of Red Guards. The night before the man jumped into a well, Yu writes, “I had seen him in the street just a few hours before. Blood was trickling down his forehead, and he was walking with a limp. In the failing light of that late afternoon, his right hand rested on his son’s scrawny shoulders, and as he talked to the boy, he wore a smile of seeming nonchalance.” [Source: Ian Johnson New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

“This violence has marked Yu’s writing career. In the 1980s his short stories (many of which are found in the collection The Past and the Punishments) were so violent that almost every character seemed to die an unnatural death. During this phase, he writes in China in Ten Words, he was plagued almost every night by nightmares, until he dreamed of his own death. That helped him recover a suppressed memory of having witnessed at close range an execution during the Cultural Revolution — he recalls in vivid detail how the victim’s head was blown open by the bullet, a gruesome image but one that finally allows him to tame the past.

“The essay “Disparity” starts in the past with him relating the heartbreaking story of how he was a member of a Cultural Revolution gang that beat up rural laborers coming to the city to buy and sell rationing coupons — defined as a counterrevolutionary act in Maoist China. One unlucky young man came to town to buy coupons so he could put on his wedding feast. Yu and his friends pummeled the man until, bloodied, he finally opened his fist to reveal the illegally obtained coupons. Yu and his hoodlum friends turned the peasant in to the authorities and then, when he was released, beat him all the way to the edge of town: “Clutching his injured hand to his chest, with a dazed and hopeless look on his face, he set out on the long road home that morning long ago.”

Yu Hua’s Literary Career

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books:““In the essay “Writing” in “China in Ten Words, explains “how he became a writer. In the early 1980s, under China’s prevailing form of socialism, he had ample free time to write while working as a dentist in the small town of Haiyan where his family had moved. He would send out manuscripts to scores of literary journals across China. Most of the time they would be returned, the postman tossing them over the wall to his family’s house. When his father heard the thud in the yard he would yell out Yu’s name followed by “Reject!” [Source: Ian Johnson New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

“After a few years, his career was launched when a Beijing literary magazine accepted three short stories for publication and brought him to the capital for a meeting. He toured the city at the magazine’s expense and was sent back home with a wad of per diem expense money. When he got home, local officials were so flabbergasted that anyone from their town was talented enough to be called to Beijing that they got him transferred to the local “culture palace,” where he was allowed to work unsupervised. That era, Yu says, “is my most beautiful memory of socialism.”

Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times: The job at the literary magazine in Beijing "soon put him on the path to paid idleness at the Cultural Bureau. Yu seems to have relished manipulating the Communist system to his own ends. I was deliberately late on the first day at the bureau office, he told me. Later I would only go once a week, and then finally only once a month to collect my salary. Yu has been kind of bad boy his whole career. He first became known in the late 1980s as a writer of surreal short fiction whose raw violence — in one story, a 4-year-old strangles his cousin, a baby, in order to enjoy the explosive crying; in another, a young girl is hacked to pieces — brashly defied the hygienic pieties of socialist realism to which China’s state-supported writers were expected to conform. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Yu switched to melodramatic realism in 1992 in his novel To Live. This atrocity-rich tale of a forbearing peasant whose son dies after a blood transfusion to save a party official was turned into an internationally successful film by Zhang Yimou, China’s most prominent director. It won the Grand Prix at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival. “In 1993 the royalties from To Live enabled Yu to leave his job altogether. My friends, he recalled, say I have enjoyed the best of both ideologies: first receiving a writer’s stipend under socialism and now royalties in the free-market regime.” In 2002 Yu Hua became the first Chinese writer to win the prestigious James Joyce Foundation Award. His novel To Live was awarded the Premio Grinzane Cavour in 1998 and was adapted for film by Zhang Yimou. To Live and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant were named two of the last decade’s ten most influential books in China.

To Live and Other Books by Yu Hua

Yu Hua wrote “Chronicle of a Blood Merchant” and “To Live”, which was made into a film by Zhang Yimou, and a collection of absurdist short stories called “the Past and the Punishments” (available in a fine translation by Berkeley’s Andrew F. Jones). “To Live” is Yu Hua’s acclaimed 1993 tale of a Chinese Everyman’s experiences through decades of revolutionary upheaval. Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in the LA Review of Books, “It’s a little gem of a book, alternately funny and poignant, which somehow manages to feel epic despite its modest page count and tight focus on a small set of characters.” The book boasts a broad scope, addressing not only the Cultural Revolution but the Nationalist era (1927-1949), as well as the early Mao years that preceded and in some ways set the stage for it. [Source: Jeffrey Wasserstrom, LA Review of Books, November 12, 2011]

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: "To Live", recounts in parable-like form the story of a peasant who endures China’s civil war and then the famines and political campaigns of early Communist rule. His main quality is his sheer will to live, making the novel a bleak commentary on recent Chinese history. The novel sold more than 200,000 copies in 2011 in China, according to his publisher, the Writers Publishing House. [Source:Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

His next novel, Chronicle of a Blood Merchant, tells the story of man who almost kills himself by selling blood to pay for his family’s survival in the Mao period; it is another book that most educated Chinese know and have read. In 2005 and 2006, he published his riskiest novel, the best-selling Brothers, a picaresque story of two stepbrothers whose lives span the latter half of the Maoist period and today’s reform era. The underlying message is that today’s naked capitalism has its roots in the brutality of early Communist rule. It can still be found on bookstands selling pirated books — high praise in a country with a short attention span.

“Like any talented novelist in China, Yu has always walked a fine line: To Live was made into an acclaimed movie by the Chinese director Zhang Yimou but it was banned in China, even though Zhang toned down Yu’s most caustic criticisms. (In the most notorious scene in the novel, the hero’s son has his blood drained by a provincial doctor eager to save the life of a top official; the movie makes his death an accident.) More recently, Brothers caused critics in China to object that the evil brother was successful while the good brother lost out — hardly the message that China’s cultural bureaucrats want. Both, however, were published and widely read.

Brothers by Yu Hua

“Brothers” has been one of China’s biggest-selling literary works. A social novel filled with sex, violence and weirdness, it was short-listed for the Man Asian Prize and was given a French award. Published in two parts in 2005 and 2006, it has sold more than a million copies in China, not counting the probably higher sales of innumerable pirated editions. An English translation came out in 2009. The very direct, matter-of-fact style unfortunately doesn’t translate very well into English. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times, “Brothers follows of two stepbrothers from the Cultural Revolution to China’s no-less-frenzied Consumer Revolution. In the opening scene, Li Guang, a business tycoon, sits on his gold-plated toilet, dreaming of space travel even as he mourns the loss of all earthly relations. Li made his money from various entrepreneurial ventures, including hosting a beauty pageant for virgins and selling scrap metal and knockoff designer suits. A quick flashback to his small-town childhood shows him ogling the bottoms of women defecating in a public toilet. Similarly grotesque images proliferate over the next 600 pages as Yu describes, first, the extended trauma of the Cultural Revolution, during which Li and his stepbrother Song Gang witness Red Guards torturing Song Gang’s father to death and observe the suicide of a man who hammers a nail into his skull. In the moral wasteland of capitalist China, Song Gang is forced to surgically enlarge one of his breasts in order to sell breast-enlargement gels.”

“The reasons for the novel’s commercial success seem clear. It invokes the widely experienced violence and suffering of the Cultural Revolution while also drawing on another resonant theme in China: the outlandish lifestyles of the rich and famous, especially nouveau-riche entrepreneurs like Li. Li represents the country’s new cultural icons, whose large appetites for money, women and cars keep the innumerable Chinese bloggers and Internet chat rooms transfixed with both admiration and revulsion.”

"Reading is good, and going a day without reading is even more uncomfortable than going a month without taking a shit." In “ Brothers” , our hero, Baldy Li, utters this affirmation in an effort to reinvent himself as a literary man and win over the town beauty, Lin Hong. Lin finds his sentiments uninspiring, so he tries out two less vulgar substitutes, to no avail. The line, however, gets straight not to the heart, perhaps, but to the bottom of what makes Brothers worth reading. This is a funny book, an assault on prudery and other social mores that is brash, surprising, and at times even revolting. Yet scatology is but one (albeit important) ingredient in a work of comparative brutality that juxtaposes the cruelty of China's revolutionary past with the injustices of its commercialized present. With Brothers, Yu Hua revives themes of death, violence, and family that permeate his earlier works. Readers will also find in abundance Yu Hua's famed black humor. The object, duration, and even tone of his humor, however, is noticeably altered. To read this novel is to plunge into an ambitious, relentless, and uneven, yet often inspired, farce. [Source: Christopher Rea, University of British Columbia, MCLC List, November 2011]

Book: “Brothers” by Yu, Hua, translated by Eileen Cheng-yin Chow and Carlos Rojas ( Pantheon Books, 2009)

Brothers Story

Christopher Rea of the University of British Columbia wrote on MCLC List, "Brothers tells the story of step-brothers Baldy Li and Song Gang, inhabitants of a fictional Liu Town, from their scrappy childhood and inseparable friendship during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) to their growing estrangement into adulthood from China's "Reform and Opening" period of the late 1970s up to the present. The book is divided into two parts, which were published as separate books in China in 2005 and 2006. Part I, set during the Cultural Revolution, concerns events of the brothers' childhood and adolescence, including the re-marriage of Li's mom, Li Lan, to Song's dad, Song Fanping; their encounters with local bullies; and the successive deaths of Song Fanping and Li Lan, which leaves them orphaned. [Source: Christopher Rea, University of British Columbia, MCLC List, November 2011]

The novel opens in the twenty-first century with the septuagenarian tycoon Baldy Li sitting on a gold-plated toilet seat and imagining himself carrying the ashes of his late brother into orbit as China's first space tourist. The true hook, however, appears soon thereafter when the narrative reverts to a formative moment in his adolescence in the 1960s. Like his late father before him, Baldy Li gets caught peeping at women's butts under the partition separating the men's and women's sections of a public toilet. Unlike his father, who falls into the shit trough and drowns,[2] Baldy Li lives to tell the tale, and tell it he does. Every adult male in Liu Town surreptitiously approaches him to learn the secret of Lin Hong's derrière, which he sells to all comers for a standard price: a bowl of house-special noodles. The incident (after which we move back in time again to Baldy Li's birth) takes on outsized importance in the narrative, because this first in a series of victories over his fellow townsfolk immediately establishes Li as a winsome rascal. Subsequent (pre-)pubescent transgressions in Part I cement his larger-than-life persona as a mischievous and enterprising trickster, a persona that is further developed in Part II.

Part I also follows another arc in a pathetic key: the abject widowhood of Li's mother, Li Lan; her reluctant courtship with the virtuous widower Song Fanping; the brief happiness of their marriage and family; the climactic trauma of his death; and the denouement of Li Lan's own final decline. In this narrative arc, society's violence escalates from the petty bullying of the boys to a murder that robs a vulnerable family of its happiness.

Part II, which is three times the length of Part I, follows the brothers diverging paths and the disintegration of their relationship into adulthood. Once an underdog, Li transforms himself into the top dog in Liu Town through a series of entrepreneurial ventures, including running a charity factory, brokering Japanese "junk suits," wholesaling scrap metal, and eventually heading a diversified conglomerate that achieves an economic monopoly over Liu Town. Song Gang, who is as weak-willed, naive, and passive as Baldy Li is resourceful, worldly, and opportunistic, manages to marry Lin Hong despite his brother's opposition, but their blissful marriage and his livelihood are eventually crippled by the new economic order Baldy Li has imposed upon Liu Town. Subjected to an escalating series of emasculating indignities, Song eventually has his woman stolen by his brother while the itinerant swindler Wandering Zhou is dragging him around the country to serve as, among other things, a male virility pill hawker and boob-implant model. Soon after returning home, he kills himself.

Farce and Tragedy in Brothers

Christopher Rea of the University of British Columbia wrote on MCLC List, "Brothers is intriguing not least as an A-list writer's first novelistic response to the questions: What has become of China since the Cultural Revolution? How is a writer to respond to a society in which the absurd has become commonplace? While exploring the dynamics of human relations through such themes as kinship, loyalty, and betrayal, the novel also offers an outlandish portrayal of contemporary society run amuck. Rather than attempt to touch on all of its myriad subplots, I focus the rest of my comments on two of the novel's notable features: the trope of the trickster, personified by Baldy Li; and the manipulation of modal registers under the rubric of farce. [Source: Christopher Rea, University of British Columbia, MCLC List, November 2011]

Farce is a compelling yet underestimated and often misunderstood creative mode. At its plainest, it is a one-note-samba of sarcastic abuse, the register most likely responsible for its generally low reputation as disconnected episodes of pointless buffoonery or laughter for laughter's sake. (Chinese terms for farce, often used in a pejorative sense, include) As scholars have been at pains to point out, however, farce may pursue a variety of agendas, not least making its audience complicit in its transgression or suspension of moral norms. Further, farcical registers may be loud or subliminal, even imperceptible. Works as different as Nabokov's Lolita and Lao She's Camel Xiangzi, for instance, have been read as works of both realism and farce. A key distinction between farce and comic modes based on "reality" (such as satire) is that the former creates its own fantasy world rather than attempts merely to represent a presumed "real world."

In Brothers, farce is primarily a mode of offence in the dual sense of seeking to offend the moral status quo, as the author defines it, and doing so aggressively — taking the offence, so to speak. This broad register is one of the easiest to recognize as farce because it bludgeons the reader/audience with outrageous conceits. The beauty contest of "virgins" with reconstructed hymens that opens in Chapter 63 is one of the novel's most obvious farcical sequences, but farce is also at work in the abjection of father and son Song, which I discuss below.

The novel's alternation between tragedy and farce has been one of its most difficult aspects for critics to reconcile. Yu Hua has likened writing the novel to composing a symphony in which passages of Wagnerian bombast push the audience to the brink before abruptly shifting to a single, sublime note of Bach, and the musical metaphor seems apt to describe the novel's repeated tonal shifts. The death of Song Fanping in Part I is one such example. Having suffered beatings, public humiliation, and incarceration for being a "landlord," the estimable man is finally beaten to death on the street, where his disfigured corpse is left for the better part of a day. When Baldy Li and Song Gang arrive and recognize the body by its clothes, they are mocked by bystanders for asking "Is that my father?" Eventually the kind-hearted vendor, Mama Su, confirms to the distraught children that it is indeed Song Fanping and persuades a man to transport his corpse home on a borrowed cart. (The man is mocked and assaulted by gawkers en route.) Li Lan, devastated, is too poor to afford a big enough coffin, so the men from the coffin shop settle on this solution:

From the outside room the man in charge yelled, "Let's start smashing!" Li Lan's body jerked as if she were being electrocuted, and Baldy Li and Song Gang's bodies jolted in response. By this time a crowd had gathered outside the house, including neighbors and passersby, as well as others attracted by the commotion. A mass of them crowded the door, and a few even tumbled into the house. They excitedly discussed how the men from the coffin shop were shattering Song Fanping's knees. Li Lan and the children hadn't realized how they were going to smash his knees, but now they heard them talking about bricks, which then shattered, and how they used the back of a cleaver. There was so much din outside that they couldn't make out clearly what everyone was saying. They could only hear people whooping and hollering, as well as the sounds of smashing, dull thuds, and occasional sharp snaps — that was the sound of bone crunching.

Reviews of Yu Hua’s China in Ten Words Review

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “China in Ten Words” is a collection of ten essays, each one based on a word that sets off musings on China, past and present. They range from basic terms like “reading,” “writing,” and “people” to more politically loaded words like “leader,” “revolution,” and “Lu Xun” — the great early-twentieth-century Chinese author. He ends with four words that sum up today’s China: “disparity,” “grassroots,” “copycat,” and “bamboozle.” Topics like this aren’t always taboo in China. Chinese novelists often explore the Cultural Revolution and problems in contemporary society. But China in Ten Words is much more explicit than these works, or any of Yu’s previous works. He writes about the Tiananmen Square massacre openly, recalling the solidarity of people in Beijing as they tried to resist the army’s approach into the city. Riding back one night from the square, he was chilled by the night air until he felt from afar a wave of heat. As he rode on, he realized the warmth came from a group of people standing to protect the Hujialou intersection from approaching soldiers: [Source: Ian Johnson New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

Melanie Kirkpatrick wrote in the Wall Street Journal, Yu "brings a novelist's sensibility to "China in Ten Words," his first work of nonfiction to be published in English. This short book is part personal memoir about the Cultural Revolution and part meditation on ordinary life in China today. It is also a wake-up call about widespread social discontent that has the potential to explode in an ugly way. The book's 10 chapters present images of ordinary life in China over the past four decades-from the violent, repressive years of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution, when the author grew up, to the upheavals and dislocations of the current economic miracle. Along the way, Mr. Yu ranges widely into politics, economics, history, culture and society. His aim, he writes, is to "clear a path through the social complexities and staggering contrasts of contemporary China." [Source: Melanie Kirkpatrick Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2011]

And he succeeds marvelously. "China in Ten Words" captures the heart of the Chinese people in an intimate, profound and often disturbing way. If you think you know China, you will be challenged to think again. If you don't know China, you will be introduced to a country that is unlike anything you have heard from travelers or read about in the news. The book's narrative structure is unusual. Each chapter is an essay organized around a single word. It's not spoiling any surprises to list the 10 words that the author has chosen in order to describe his homeland: people, leader, reading, writing, revolution, disparity, grassroots, copycat, bamboozle and Lu Xun (an influential early 20th-century writer). None is likely to appear on the list of banned words and phrases that China's censors enforce when they monitor Internet use. But in Mr. Yu's treatment, each word can be subversive, serving as a springboard for devastating critiques of Chinese society and, especially, China's government.

Mr. Yu lives in Beijing and knew he would be allowed to publish "China in Ten Words" in China. Jeffrey Wasserstrom, wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: ”China in Ten Words” "manages to convey a great deal of information and insight in just over 200 pages. Each of the terms he singles out for attentionfunction more as a counterpart to Proust’s famous Madeleine than as an object of dispassionate linguistic analysis. They serve above all as spurs to memory — opportunities to tell illuminating stories about the past. It's rare to find a work of fiction that can be hysterically funny at some points, while deeply moving and disturbing at others. It’s even more unusual to find such qualities in a work of non-fiction. But China in Ten Words is just such an extraordinary work.

“”China in Ten Words” In many cases, especially early in the book, the terms resurrect incidents that took place in Yu Hua’s provincial hometown during the Cultural Revolution decade, the period of his childhood and adolescence . Take, for example, the chapter he devotes to the word “Leader.” When Yu Hua was young, this term was reserved exclusively for references to one individual: Mao Zedong. Moving deftly between the humorous and the disturbing, as he does throughout the volume, Yu Hua pokes fun at himself for being so swept up in the personality cult mania of the time, recalling how he suspected the fates of giving him a raw deal by forcing him to be born into a “Yu” rather than a “Mao” family.

In contrast and by way of self-critique, Yu Hua also offers the tale of a local official who discovers that sharing the Great Helmsman’s surname can be a curse rather than a blessing. Since the official headed a local committee, some people jokingly called out to him as “Chairman Mao” when he passed them on the street. At the height of the Cultural Revolution, the poor man was castigated for putting on airs, pretending to be a “local” Chairman Mao. His defense was that he had never asked people to call him that nor had he called himself by that term. In that supercharged political environment, though, this did him no good, as his accusers pointed out that when passersby had called him “Chairman Mao,” the local official had answered without correcting them for misspeaking.

Yu Hua on the Books and Writers He Admires

Pankaj Mishra wrote in the New York Times: “Yu was drawn to the icons of Western high modernism whose work began to appear in translation in China in the 1980s, in particular Kafka, Bruno Schulz and Borges. The delicate fictions of the Japanese writer Yasunari Kawabata were also a great early influence. Kawabata taught me the importance of detail, Yu recalled. I would buy two copies of his novels whenever I saw them. One to read and the other to keep in pristine condition on my shelf.” [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

On his influences and books and writers he respects and likes to read, Yu Hua told the Los Angeles Review of Books: Among classical literature, I most appreciate works of “biji.” [Ed. note: a work that may include short stories, literary criticism, anecdotes and sketches, philosophical musings] — from Tang and Song dynasty legends to Ming and Qing dynasty biji, they are brief and vivid. “There are also many writers — too many to even name a few. As for classical essays, a good place to start is the Guwen Guanzhi, a must-read [Ed. note: Guwen Guanzhi is an anthology of essays first published during the Qing dynasty that includes works from Warring States period through the Ming dynasty]. As for the 20th century, my favorite writer is Lu Xun. Every word he wrote was like a bullet, like a bullet straight to the heart. [Source: Megan Shank, Los Angeles Review of Books, October 25, 2013]

“Contemporary Chinese literature is rich and colorful. There are all types of writers, so there are all types of writing, too. As I see it, the biggest problem facing Chinese literature is how to express today’s realities. Reality is more preposterous than fiction. It’s a difficult task to convey reality’s absurdity in a novel. China has never had a shortage of excellent women writers, like Eileen Zhang, whom you’ve mentioned. Now there is also Wang Anyi. I think in the realm of literature, sex isn’t important. For example, in Wang Anyi’s work, it’s very difficult to tell that the writer is a woman. Excellent writers should be neutral — and be able to write men and women. And when you’re writing, you’re not writing as a man or a woman.

Yu Hua on Readers and Writers in China

On what he sees around him in China, Yu Hua told the Los Angeles Review of Books: On the subway, I see everyone reading on cell phones. You almost never see someone holding a real book. It’s hard to imagine using a cell phone to read Anna Karenina. I think the majority of these readers are reading “fast food” novels. Because they’re always using their phones, today’s youth are inflicting a lot of damage on their thumb joints. The ache is already starting to bother them, so maybe one day they’ll return to a more regular way of reading books. Reading on a Kindle isn’t bad. [Source: Megan Shank, Los Angeles Review of Books, October 25, 2013]

Books on how to make money and how to succeed are very popular, while serious fiction and non-fiction have seen their readerships decrease. This seems to be the same the world over. But at least it’s only a decline — not an abrupt and utter abandonment. There will always be new readers growing up who appreciate serious literature, so I’m not at all pessimistic. Today a high school student left a message on my weibo [Ed. note: microblog]. He said that he and his classmates had enjoyed reading my book Brothers together. But when the teacher discovered the book, the teacher confiscated it and told the young man that bringing such a book into the school was like poisoning himself and his classmates. The teacher required them to only read textbooks so that they can test well, but these students are still reading works of literature.

On writers, he said: “In China, young writers develop on their own. They’re not cultivated. That’s because literary education at Chinese universities isn’t the same as it is in the States. In the States, excellent authors and poets serve as professors. At Chinese universities, most of the literature professors teach theory, criticism and history.

Yu Hua on Modern China

In her review of “ China in Ten Words” by Yu Hua, Melanie Kirkpatrick wrote in the Wall Street Journal, Mr. Yu's portrait of contemporary Chinese society is deeply pessimistic. The competition is so intense that, for most people, he says, survival is "like war." He has few hopeful words to offer, other than to quote the ancient philosopher Mencius, who taught that human progress is built on man's desire to correct his mistakes. Meanwhile, he writes, "China's pain Is mine." [Source: Melanie Kirkpatrick Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2011]

“Mr. Yu argues that corruption infects every aspect of modern Chinese society, including the legal system. Historically, Chinese peasants with grievances could go to the capital and petition the emperor for redress. Today, Mr. Yu writes, millions-yes, millions-of desperate citizens flock to Beijing each year hoping to find an honest official who will dispense justice where the law has failed them at home. What will happen when they discover that their leaders at the national level are just as corrupt as those at the local level?

“Just consider,” Yu Hua writes, “how urbanization has been pursued, with huge swathes of old housing razed in no time at all and replaced in short order by high rise buildings.” The term “blood-stained GDP” is becoming a popular one in Chinese online debates, coined to described the high human toll of the government’s rush to make the country look as “modern” as possible as quickly as possible. Yu Hua doesn’t employ this newly minted phrase, but he uses ones that are just as highly charged. He writes, for example, of a “developmental model saturated with revolutionary violence of the Cultural Revolution type,” in which many ordinary individuals are once again suffering in the name of abstractions.

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books:“In “Copycat,” Yu suggests that not only are cell phones and software pirated in China; even ideas like environmentalism and political reform are circulated in tamed and tepid versions. This calls into question many major government projects to modernize the country, with Yu essentially saying they are a sham. The reason, he says, is that Chinese haven’t fully discussed or understood what their country is doing. Just as during the Cultural Revolution people blindly followed Mao, today they reflexively embrace market economics. “After participating in one mass movement during the Cultural Revolution, for example, we are now engaged in another: economic development.” This may be a bit simplistic, but his drawing of parallels between the past and present is rare and unwelcome to the regime. In official discourse, an entirely new historical period started in 1978 with Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms. [Source: Ian Johnson New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

Yu Hua on Censorship in China

Yu Hua wrote in the New York Times: Censorship in China conjures the image of rigid, unsmiling authority, but that disapproving scowl can give way to a different expression — and not always a consistent one. A film, for example, might be banned for 20 years, while the novel on which it is based sells briskly throughout that same period. This might seem puzzling, but the reason is simple. China has more than 500 publishing houses, each with its own editor in chief (and de facto censor); if a book is rejected by one publisher there’s still a chance another will take it. In contrast, films are not released until officials in the state cinema bureau in Beijing are satisfied, and once a film is banned it has no hope of being screened. [Source: Yu Hua, New York Times, February 28, 2013]

“When it comes to censorship in China, the primary factors are often economic, not political. Publishing houses that were once government financed have operated as commercial enterprises for years now. Editors are under pressure to make the biggest profit they can. Even if a book carries some political risks, a daring editor will take the gamble if there’s a chance it will be a best seller.

“To be sure, there are some limits in book publishing — the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 are taboo, for example — but fewer than in film. That’s because film censors, unlike book publishers, don’t have to worry about making profits. Each script is scrutinized, and only after it’s approved can filming commence. Review of the finished product is even more exacting. Even if they were to reject every project that comes their way, it wouldn’t affect their salaries, so they are not prepared to take on the least political risk. That’s why the Cultural Revolution and other sensitive topics are regularly discussed in print but remain off-limits on film. If you go to a cinema, all you’ll see, basically, are martial-arts films, palace dramas, love stories and comedies — and a few American movies.

“Television censorship is a bit less strict. Programming directors decide what gets broadcast, but the propaganda ministry often demands changes. China Central Television, the state broadcaster, is the most carefully monitored; regional stations have more leeway. News programming undergoes the strictest censorship, while other programs — particularly sports — have more freedom.

“Newspaper censorship is also relatively more relaxed than film censorship, but stricter than book censorship. Stricter because the Communist Party puts more stress on control of the press (“journalism is the Party’s mouthpiece,” the saying goes). More relaxed because the press has to make its way in the marketplace. Newspapers need circulation and advertising revenue, so they publish lots of stories about social problems and injustices, because that’s what readers want. When newspapers got government subsidies, they were politically and economically beholden. Now their subservience can’t be counted on. As the economic base crumbles, the superstructure threatens to collapse.

“The newspaper Southern Weekend, based in Guangdong Province, for years published exposés on corruption and malfeasance, becoming one of China’s most popular news outlets. Shrewdly, it focused its muckraking on other provinces, with the result that local censors often cut it slack. Papers elsewhere began to take their lead from Southern Weekend, dispatching investigative reporters far afield while carrying upbeat news about the situation close to home.

“The highly publicized demonstrations in January over censorship of Southern Weekend were a rarity: a “mass incident” (as China calls such protests) over the media. A propaganda chief who’d parachuted in from Beijing had meddled so crudely with a routine editorial that he triggered a revolt among editors and reporters. Other newspapers lent support to the protesters, while on the Internet the outrage was even stronger. Soon it was all hushed up. The paper has continued to publish. The authorities offered vague commitments of gentler censorship, but have quietly begun retaliating against those who took a stand. The government won in the end, but its censorship had encountered — for the first time in decades — head-on resistance from a press that has become far less docile.

“On Weibo, a kind of Chinese Twitter, I recently made a joking comparison between media censorship and the pervasive threat of contaminated food, a constant source of worry: “There’s no end to these food scares,” a friend sighed. “Is there any hope of a solution?” “Oh, all we need is for food inspections to be as forceful as film censorship,” I told him breezily. “With all that faultfinding and nit-picking, food-safety issues will be resolved in no time.” More than 12,000 readers reposted this. One wrote: I know what we should do. Let’s have those in charge of film, newspaper and book censorship take over food safety, and have those responsible for food safety censor films, papers and books. That way we’ll have food safety — and freedom of expression as well!

Yu Hua on Change and Suicide in China

Yu Hua wrote in The Guardian in 2018: In my 58 years, I have experienced three dramatic changes, and each one has been accompanied by a surge in suicides among officials. The first time was during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. At the start of that period, many members of the Chinese Communist party woke up one day to find they had been purged: overnight they had become “power-holders taking the capitalist road”. After suffering every kind of psychological and physical abuse, some chose to take their own lives. In the small town in south China where I grew up, some hanged themselves or swallowed insecticide, while others threw themselves down wells: wells in south China have narrow mouths, and if you dive into one headfirst, there is no way you will come out alive. [Source: Yu Hua, The Guardian, September 6, 2018]

“In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, many people from the lowest tiers of society formed their own mass organisations, proclaiming themselves commanders of a “Cultural Revolution headquarters”. These individuals — rebels, they were called — often went on to secure official positions of one kind or another. They enjoyed only a brief career, however. Following Mao’s death in 1976, the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution and the emergence of the reform-minded Deng Xiaoping as China’s new leader, some rebels believed they would suffer just as much as the officials they had tormented a few years before.

“Thus came the second surge in suicides — this time of officials who had clawed their way to power as revolutionary radicals. One official in my little town drowned himself in the sea: he smoked a lot of cigarettes first, and the stubs littering the shore marked the agony of indecision that preceded his death. This was a much smaller surge in suicides than the first one, because Deng was not out for political revenge, focusing instead on kickstarting economic reforms and opening up to the west. This policy led in turn to China’s economic miracle, the downside of which has been environmental pollution, growing inequality and pervasive corruption.

“In late 2012 came the third dramatic change in my lifetime, when China entered the era of Xi Jinping. No sooner did Xi become general secretary of the Communist party than our new leader launched an anti-corruption drive, the scale and force of which took almost everyone by surprise. The third surge in suicides followed. When officials who had stuffed their pockets during China’s breakneck economic rise discovered they were being investigated and realised they could not wriggle free, some put an end to things by suicide. In cases involving lower-ranking officials who were under investigation but had not yet been taken into custody, the government explanation was that their suicides were triggered by depression. But, if a high-ranking official took his own life, a harsher judgment was passed. On 23 November 2017, after Zhang Yang, a general, hanged himself in his own home, the People’s Liberation Army Daily reported that he “had evaded party discipline and the laws of the nation” and described his suicide as “a disgraceful action”.

“These three surges in suicide demonstrate the failure and impotence of legal institutions in China. The public security organs, prosecutorial agencies and courts all stopped functioning at the start of the Cultural Revolution; thereafter, laws existed only in name. Since Mao’s death, a robust legal system has never truly been established and, today, law’s failure manifests itself in two ways. First, the law is strong only on paper: in practice, law tends to be subservient to the power that officials wield. Second, when officials realise they are being investigated and know their position won’t save them, some will choose to die rather than submit to legal sanctions, for officials who believe in power don’t believe in law. These two points, seemingly at odds, are actually two sides of the same coin. The difference between the three surges in suicide is this: the first two were outcomes of a political struggle; framed by the start and the end of the Cultural Revolution. The third, by contrast, stems from the blight of corruption that has accompanied 30 years of rapid economic development.

Yu Hua: “How My Books Have Roamed the World”

Yu Hua wrote in Specimen: “I counted the number of countries and languages, apart from China and Chinese (and China’s ethnic minority languages) that my books have been published in so far, and it came to 38 countries and 35 languages. The reason there are more countries than languages is mainly because English editions are published in North America (US and Canada), the UK, Australia and New Zealand; Portuguese editions are published in Brazil and Portugal; and Arabic editions in Egypt and Kuwait. But sometimes the situation is reversed: my books are published in two languages in Spain (Castilian and Catalan) and in India (Malayam and Tamil). [Source: Yu Hua, Specimen, September 21, 2017, Translated into English by Helen Wang]

“Looking back on how my books have roamed the world, I see there are three factors: translation, publication and readers. I’ve noticed that in China discussions about Chinese literature in a world context focus on the importance of translation, and of course, translation is important, but if a publisher doesn’t publish, then it doesn’t matter how good a translation is, if it’s going to be locked in a drawer, old-style, or, these days, stored on a hard drive. Then there are the readers. If a publisher publishes a book, and the readers don’t pick up on it, then the publisher will lose money and won’t want to publish any more Chinese literature. So, these three factors — translation, publication and readers — are all essential.

“My first publications in translation came out in 1994, in three countries: France, the Netherlands and Greece. 23 years later, 11 of my books have been published in France, 4 have been published in the Netherlands, and just the one has been published in Greece. Two of my books were published in France in 1994. To Live was published by the biggest publisher in France, and a collection of short stories, World Like Mist, was published by a very small publisher, which was almost a one-man-band. In 1995, when I was in France to take part in the St Malo Literary Festival, I went to Paris to visit the big publisher and met with the editor. At the time I was writing Chronicle of a Blood Merchant and asked if he’d like to publish my next novel. He asked me in a strange way: “Can your next novel be made into a movie?” I could see I had no future with that publisher. Then I went to see the little publisher, and asked if they’d like to publish my next novel. Their answer was very modest: they were only a small publishing house, and wanted to publish other authors as well, and couldn’t devote so much attention to me. At the time I thought I had no future in France. Then, luck came my way. The prestigious French publishing house Actes Sud started a Chinese literature series, and invited Isabelle Rabut, Professor of Sinology at the École des Langues Orientales, in Paris, to be the series editor. She was familiar with my work, knew that Chronicle of a Blood Merchant had just been published in the literary journal Shouhuo [Harvest], asked Actes Sud to buy the rights, and a year or so later it was published in French. After that, Actes Sud published one after another of my books. I had found my publisher in France after all.

“After publishing To Live in 1994, the Dutch publisher De Geus went on to publish Chronicle of a Blood Merchant, Brothers, and The Seventh Day. It’s interesting that in these 23 years I haven’t had any contact at all with De Geus, I don’t even know who the editor is, or the translator, probably because it all goes through an agent. I tried to work it out. I know only one Dutch Sinologist, Mark Leenhouts, but he doesn’t translate my books. When I saw him last July in Changchun, in China, he said he hoped I might visit the Netherlands next time I’m in Europe, and we arranged to meet this September. I asked him about my Dutch translator, and he smiled and gave the name Jan De Meyer. He said Jan is a Belgian, who speaks Dutch and lives in France. A very interesting person! This April De Geus asked Jan to edit a collection of my short stories, and I received my first email from him. The first line read: “You don’t know me. I’m the person who translated your books Brothers and The Seventh Day into Dutch.” That was the sum total of his self-introduction.

“There’s an even more interesting story about my book in Greek. About ten or so years ago, the Greek publisher Hestia decided to publish To Live. They signed a contract with me, had a translator lined up, and then suddenly discovered that another publishing house, Liviani, had published it in 1994. I didn’t know anything about it, or even who had sold Liviani the rights. Hestia pulled out, Liviani sent me some copies of the book, and then both publishing houses forgot about me, and I forgot about them. I only remembered them when I was putting together material for this paper.

“Finding a good translator is very important. M.R. Masci and N. Pesaro (Italy), Ulrich Kautz (Germany), Andrew Jones and Michael Berry (USA), Iizuka Yutori (Japan) and Paik Wondam (Korea) all translated an entire book of mine before looking for a publisher. My current English translator, Alan Barr, wrote to me, with an introduction from Andrew Jones. He translated a collection of my short stories that then took ten years to be published. Translators like Barr, who translate with passion, without caring when the translation will be published, are very rare, because good translators are usually well-known, or soon will be, and some of them will translate books by many authors. So, they won’t translate until they have a contract from a publisher — which makes it even more important to find the right publisher for you. In France, I’ve had four different translators, but have been with the same publishing house, Actes Sud. In the USA too, I’ve had four translators, and one publisher, Random House. When you’ve got a steady publisher, you can keep publishing your books.

“To Live (tr. Michael Berry) and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant (tr. Andrew Jones) were translated into English in the 1990s, but I kept hitting a brick wall with the American publisher. One of their editors even wrote to me, asking: “Why do the characters in your novel have only family responsibilities, and no social responsibilities?” I realized there were historical and cultural differences, and wrote back, saying that China is a country with a history going back 3000 years, and that a lengthy period of feudalism had obliterated individuality in society, that individuals did not have freedom of speech in their social lives, only in their home lives. I told him that those two books were set in the late 70s, and that everything had changed since the 90s. I tried to persuade him, but didn’t succeed. I continued to hit a brick wall in the US, until 2002 when I met my current editor, LuAnn, and thanks to her, I got a foothold at Random House.

“A key part of finding the right publisher for you is to find an editor who appreciates your work. My first books in Germany — To Live and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant — were published by Klett-Cotta in the late 90s, but they didn’t publish any of my other books. A few years later I found out why. It turned out that my editor, Thomas, had died. My later books have all gone to S. Fischer, because they have a good editor called Kupski, and whenever I go to Germany, she takes a train to wherever I am — no matter how far away — and comes to meet me, often arriving in the evening, and leaving the next morning before dawn on a train back to Frankfurt.

“In 2010 I went to Spain to promote my new book. I met my editor Elena in Barcelona, and over dinner I joked about the conversation I’d had in 1995 with the biggest publishing house in France. She listened in horror, her hand over her mouth, her eyes widening, barely able to believe that such editors still existed. I knew instantly that Saix Barral was the right publisher for me in Spanish, although they had only published two of my books at the time.

“I’ll say a few words now about my interactions with readers. I’m often asked if Chinese readers and foreign readers ask the same kind of questions. I’ve been asked this overseas and in China, and there’s some misunderstanding here. People think that I’m often asked social and political questions overseas, but not in China. In fact, readers in China ask just as many social and political questions as foreign readers. Literature encompasses everything. When we read in a literary work that three people walk past another person, we know that three plus one makes four people — that’s maths. When we read about sugar dissolving in hot water, that’s chemistry. When we read about leaves falling, that’s physics. Literature can’t avoid maths, physics and chemistry. It can’t avoid society and politics either. At its heart, literature is literature, whether it’s Chinese or foreign, and what concerns readers most are the things that belong to literature: the characters, their fate and the story. If we’re talking about the novel itself, then I don’t think there’s any difference between the questions asked by Chinese readers and foreign readers. If there are differences, they are between individual readers. For us Chinese, when we read foreign literature, what is it that draws us in? Very simply, it’s literature. As I’ve said before, if there is a mysterious power in literature, then it’s the power that allows us to read about our own feelings in works by authors of different periods, different ethnic groups, different cultures, and different histories.

“When talking with foreign readers, there are often some lighter questions too. For example, they might ask what would be different about the same event if it was taking place in China? I tell them that China’s population is huge, and that more people give up trying to get to a venue in China than actually make it to a venue overseas. Another question I’m often asked is: what has been my deepest impression on meeting a reader? I say it was in 1995 when I went abroad for the first time, to France, and I was at a book signing event in a tent at the St Malo literary festival, sitting behind a pile of my own books in French, watching French readers coming and going. Some of them would pick up my book, look at it, and then put it down again. I waited and waited, and then finally two young French boys came over with a piece of blank paper, and told me through the translator that they’d never seen any Chinese writing, and asked if I would write a couple of Chinese characters for them. It was the first time I was asked to sign my name overseas. Of course, I didn’t write my own name, I wrote Zhong guo [China].

Partying with Yu Hua and Some Cadres in Hangzhou

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: In 2011, “I went with the Chinese writer Yu Hua to his hometown of Hangzhou, some one hundred miles southwest of Shanghai, and realized that his bawdy books might not be purely fictional; their characters and situations seemed to follow him around in real life too. “We stayed in a villa in a secluded development built on part of a wetlands park. The string of houses, bridges, and canals was surrounded by high walls and walkie-talkie-wielding guards. Yu’s neighbors were film producers, directors, artists, writers, and government officials — all beneficiaries of a city-run company that owned the properties and lent them out to anyone it figured might lend luster to Hangzhou, do something artistic, or simply had the pull to live in a luxury development. Yu is one of China’s most famous writers and even though his relationship to the city is tenuous — he was born in Hangzhou but left as an infant for a small town and now lives in Beijing — officials hoped he’d give their city some cachet. [Source: Ian Johnson New York Review of Books, October 11, 2012]

“Over the next few days, the villa was the setting for a series of meals, one raunchier than the next. The high point was a boozy lunch where the head of the local writer’s association ogled the legs of the deputy head of propaganda, while a paunchy singer for the People’s Liberation Army showed off a “talented young lady” he had taken under his wing. Later, a Party secretary arrived with a suitcase full of French wine and an enormous celadon vase from the onetime imperial kilns of Jingdezhen — the sort of trophy that governments in China fob off on famous visitors and hotel lobbies.

When everyone was suitably drunk, Yu quieted the room with an announcement. “We were just at West Lake,” he said, referring to the city’s most famous tourist site. “I haven’t seen so many people in one place since June 4” — the 1989 massacre of antigovernment protesters in Beijing. “Ha-ha, Yu Hua, only you,” the writer’s association chairman cackled as he cocked his head in Yu’s direction. “I live next door to him. Always joking.” “What are you saying?” Yu said crossly. “Your only contribution to society is to file fake meal receipts.” The chairman widened his eyes and was about to counterattack but everyone began laughing at him. He meekly bowed his head, whimpering: “We’re neighbors, we’re neighbors. Ha-ha. He’s joking.”

“And so it went for another hour as Yu treated the local notables to jokes, innuendos about corruption, and the failings of the Communist Party. When the wine bottles had been emptied, the prawns sucked dry, and a bottle of grain alcohol lay on its side, the guests staggered out to their government-issue Audi A6L limousines, windows tinted and doors held open by drivers in dark aviator glasses. Yu saw them off with a wave and then wondered aloud: “Who the fuck were these people? I can’t believe I actually toasted them!”

Image Sources: Amazon

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021