CHRISTIANITY IN CHINA

8th century cross in China

Despite the Catholic and Protestant missionaries, who began arriving in large numbers in China in the middle of the nineteenth century, Christianity has managed to gain only a handful of converts. Christians are mostly concentrated in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai and are most numerous in Wenzhou and Zhejiang province. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

The Chinese were exposed to Christianity and Islam during the A.D. 7th and 8th century. The earliest traces of Christianity date back to a 7th-century visit by a Syrian named Raban, who presented Christian scriptures to the imperial court. But ultimately they found both Islam and Christianity unappealing as they did with Zoroastrianism and Manicheanism” the belief that good and evil exists in all humans, and that life is a struggle between the spirit and the flesh. All these faiths arrived in China on Silk Road. Emperors during the Tang dynasty (618-907) for the most part tolerated members all sorts of religious sects — Taoist and Confucian scholars, Christian missionaries, Zoroastrian priests, and Buddhist monks. On his trip to China in the 13th century Marco Polo wrote: "The people are for the most part idolaters, but there are also some Nestorian Christians and Saracens [Muslims]."

Good Websites and Sources: Chinese Government White Paper on Religion china-embassy.org ; United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religion Facts religionfacts.com; ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy stanford.edu ; Academic Info academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Chinatxt Ancient Chinese History and Religion chinatxt ; Christianity in China Christianity in China Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; History of Christianity in China Ricci Roundtable

See Separate Article CHRISTIANITY, CHRISTIANS AND BIBLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; BRIEF HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; RELIGION AND COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; RESTRICTIONS AND REPRESSION ON RELIGION AND REFORM EFFORTS ON CHINA factsanddetails.com; HOUSE CHURCHES AND PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CATHOLICS AND RELATIONS BETWEEN THE VATICAN AND BEIJING factsanddetails.com; PERSECUTION OF CATHOLICS IN CHINA AND CONFLICTS OVER BISHOPS factsanddetails.com; MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONTROL AND REPRESSION OF ISLAM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JEWS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A Jesuit in the Forbidden City: Matteo Ricci, 1552-1610" by R. Po-chia Hsia Amazon.com; “The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com; “Matteo Ricci and the Catholic Mission to China, 1583–1610: A Short History with Documents by Ronnie Po-Chia Hsia Amazon.com; “China's Christian Martyrs: 1300 years of Christians in China who have died for their faith” by Paul Hattaway Amazon.com; “The History of Christian Missions in Guangxi, China” by Arthur Lin Amazon.com; “God Is Red: The Secret Story of How Christianity Survived and Flourished in Communist China” by Liao Yiwu and Wen Huang Amazon.com; “Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao's China” by Lian Xi Amazon.com “Inside China's House Church Network” by Yalin Xin Amazon.com; “Religion and the State in Russia and China: Suppression, Survival, and Revival” by Christopher Marsh Amazon.com ; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “China's Urban Christians: A Light That Cannot Be Hidden” by Brent Fulton Amazon.com; “Jesus in Beijing: How Christianity Is Transforming China And Changing the Global Balance of Power” – Illustrated, by David Aikman Amazon.com

Early Christians in China

Nestorian stele

Nestorian Christians (a sect originally from Syria) arrived in China on the Silk Road in the A.D. 7th century. According to the Nestorian Stone, a 10-meter-high tablet discovered in the 17th century and dated to A.D. 781, Nestorian missionaries, led by one Bishop Alopen, arrived from present-day Afghanistan in A.D. 635.

Nestorian Christianity is largely extinct but at one time it was quite a powerful Christian sect and was at the center of important doctrinal controversies. The Nestorians emphasized the duality of being between man and divine. They were regarded as heretics by other sects for their belief that there were two separate persons in the incarnate Christ, denying that Christ was in one person both God and man. They went on to argue that Mary was either the mother of God (a blasphemous concept to many Christians) or the mother of the man Jesus; but she couldn't have it both ways.

The first Nestorian church in China was founded in 638 in Changsan (Xian) by a Syrian named Raban. Nestorian Christians translated the Bible into Chinese. Their religion was officially tolerated by the Tang dynasty emperors for over 200 years until they were suddenly ordered to return home in 845.

An altar with a nativity scene and an image of the Virgin Mary was discovered in the late 1990s in an ancient pagoda, dated to A.D. 638, in Lou Guan Tai, a two hour drive south of Xian. The pagoda was oriented toward the east like a church rather than north and south like a Chinese temple, which is seen as evidence that it was a church before it became a pagoda. The discovery was viewed as an indication that the Nestorians were not a fringe movement but rather one that penetrated deep into China. Archaeologists have also discovered passages from the Psalms written in the Nestorian’s Syriac language in Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, which showed that Christianity spread as far north as Mongolia.

Marco Polo wrote there were some 700,000 Christian in China when he visited in the 13th century. Describing an encounter with some he wrote: his father and uncle "enquired from what source they had received their faith and their rule, and their informants replied: 'From our forefathers.' It came out that they had in a certain temple three pictures representing three apostles...who had instructed their ancestors on the faith long ago, and it had been persevered among them for 700 years." These Christians were most likely Nestorians.

William of Rubruck on Nestorian Christians in Asia

Nestorian in western China

William of Rubruck (c. 1220 – c. 1293, or ca. 1210-ca. 1270) was a Flemish Franciscan missionary, monk and explorer. His account is one of the masterpieces of medieval geographical literature comparable to that of Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta and is the most detailed and valuable of the early Western accounts of the Mongols. Born in Rubrouck, Flanders, he is known also as William of Rubruk, Willem van Ruysbroeck, Guillaume de Rubrouck or Willielmus de Rubruquis. He traveled to various places of the Mongol Empire in Asia before his return to Europe. [Source: Wikipedia]

William of Rubruck wrote: On the feast of Saint Andrew (30th November) we left this city ( Cailac, Qayaligh, near present-day Kapal in Kazakhstan), and at about three leagues from it we found a village entirely of Nestorians. We entered their church, singing joyfully and at the tops of our voices: "Salve, regina!" for it had been a long time since we had seen a church...Living mixed among” the Mongols and Tartars “though of alien status (tanquam advene), are Nestorians and Saracens (Muslims) all the way to Cathay. In fifteen cities of Cathay there are Nestorians, and they have an episcopal see in a city called Segin [=Hsi-king], but for the rest they are purely idolaters. The priests of idols of the nations spoken of all wear wide saffron-colored cowls. [Source: “The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253-55" by William of Rubruck, translation by W. W. Rockhill, 1900; depts.washington.edu/silkroad /~]

“There are also among them, as I gathered, some hermits who live in forests and mountains and leading lives that are extraordinarily ascetic. The Nestorians there know nothing. They say their offices, and have sacred books in Syrian, but they do not know the language, so they chant like those monks among us who do not know grammar, and they are absolutely depraved. In the first place they are usurers and drunkards; some even among them who live with the Tartars have several wives like them. /~\

“When they enter church, they wash their lower parts like Saracens (Muslims); they eat meat on Friday, and have their feasts on that day in Saracen fashion. The bishop rarely visits these parts, hardly once in fifty years. When he does, they have all the male children, even those in the cradle, ordained priests, so nearly all the males among them are priests. Then they marry, which is clearly against the statutes of the Fathers, and they are bigamists, for when the first wife dies these priests take another. They are all simoniacs, for they administer no sacrament gratis. They are solicitous for their wives and children, and are consequently more intent on the increase of their wealth than of the faith. And so those of them who educate some of the sons of the noble Mongol, though they teach them the Gospel and the articles of the faith, through their evil lives and their cupidity estrange them from the Christian faith, for the lives that the Mongol themselves and the Tuins [=Buddhists, from Chinese T'ao-yen: "man of the path." The term properly refers only to priests but Rubruck applies it here to all Buddhists] or idolaters lead are more innocent than theirs. /~\

See Separate Article WILLIAM OF RUBRUCK ON MUSLIMS, BUDDHISTS, NESTORIANS AND PEOPLE OF THE EAST factsanddetails.com

Early Jesuits, Christians and Missionaries in China

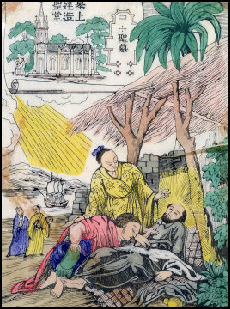

St. Xavier dying in China Jesuit missionaries were among the first foreigners to arrive in China.Their advise was sought on scientific and astronomical matters Their knowledge about astronomy was particularly valued because the Emperor needed knowledge about the seasons and the movement of celestial objects to set the dates for important rituals. At first the Jesuits were not allowed to preach and later when they were they won few converts. According to Columbia University: “Beginning in late sixteenth century, Portuguese merchants began coming to trade in southern China, bringing Jesuit priests along with them. Jesuits, notably the Italian Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), aimed to convert members of the scholar-official elite who, they hoped, would then assist in spreading their religion among the people. "

St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552) — the famous Spanish Jesuit missionary who devoted his life to spreading Christianity in Asia — died at the age of 46 on the island Sancian off Guandong province in China in present-day Macau during a proselytizing mission. After he died his body was packed in lime and shipped to Goa. His body was buried and later exhumed by Jesuits who cut off his right arm and sent it to the Pope as a gift. What remained of the body was placed in a gold and glass coffin in a Goa cathedral. Known as the sainted Apostle of the Indies, St. Francis Xavier was the youngest son of a Basque aristocrat. When he was 28 he helped found the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). In 1542 he arrived in Goa and buried many dead Portuguese voyagers in India. He went to Japan in 1549 and helped Christianity advance very quickly there, especially in southern Japan. He also went to Indonesia and Sri Lanka. The Spanish Dominican Navarrette lived and worked in China from 1659 to 1664. He wrote: "It is God's special Providence that the Chinese don't know what is done in Christendom, for if they did there would be never a man among them but would spit in our faces."

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “ In 1613, after Ricci's death, the Jesuits and some Chinese whom they had converted were commissioned to reform the Chinese calendar. In the time of the Mongols, Arabs had been at work in Beijing as astronomers, and their influence had continued under the Ming until the Europeans came. By his astronomical labours Ricci won a place of honour in Chinese literature; he is the European most often mentioned. The missionary work was less effective. The missionaries penetrated by the old trade routes from Canton and Macao into the province of Jiangxi and then into Nanking. Jiangxi and Nanking were their chief centres. They soon realized that missionary activity that began in the lower strata would have no success; it was necessary to work from above, beginning with the emperor, and then, they hoped, the whole country could be converted to Christianity. When later the emperors of the Ming dynasty were expelled and fugitives in South China, one of the pretenders to the throne was actually converted—but it was politically too late. The image to the right is an early Christian cross with a swastika. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

The missionaries had, moreover, mistaken ideas as to the nature of Chinese religion; we know today that a universal adoption of Christianity in China would have been impossible even if an emperor had personally adopted that foreign faith: there were emperors who had been interested in Buddhism or in Taoism, but that had been their private affair and had never prevented them, as heads of the state, from promoting the religious system which politically was the most expedient—that is to say, usually Confucianism. What we have said here in regard to the Christian mission at the Ming court is applicable also to the missionaries at the court of the first Manchu emperors, in the seventeenth century. Early in the eighteenth century missionary activity was prohibited—not for religious but for political reasons, and only under the pressure of the Capitulations in the nineteenth century were the missionaries enabled to resume their labours.

The missionaries had, moreover, mistaken ideas as to the nature of Chinese religion; we know today that a universal adoption of Christianity in China would have been impossible even if an emperor had personally adopted that foreign faith: there were emperors who had been interested in Buddhism or in Taoism, but that had been their private affair and had never prevented them, as heads of the state, from promoting the religious system which politically was the most expedient—that is to say, usually Confucianism. What we have said here in regard to the Christian mission at the Ming court is applicable also to the missionaries at the court of the first Manchu emperors, in the seventeenth century. Early in the eighteenth century missionary activity was prohibited—not for religious but for political reasons, and only under the pressure of the Capitulations in the nineteenth century were the missionaries enabled to resume their labours.

Matthew Ehret-Kump wrote in China Channel: “By 1704, Pope Clement IV issued a decree proclaiming that anyone in China wishing to practice Christianity had to entirely renounce the ancestral rites, causing the entire 150 year Jesuit mission to crumble to pieces. Soon, only a handful of the most valuable missionaries were permitted to stay in Beijing, while the rest of China was made off limits to them. [Source: Matthew Ehret-Kump China Channel, April 18, 2020]

See Separate Article EUROPEAN PRESENCE IN CHINA IN THE MING AND EARLY QING DYNASTY (16th-18th CENTURIES) factsanddetails.com

17th Century Anti-Christian Denouncement from China

According to Columbia University: “ While welcomed by the late Ming and early Qing emperors for their expertise in areas such as astronomy, calendar-making, cannon and other firearms, and mathematics, the Jesuits made relatively few converts. By the late seventeenth century, Christianity faced growing opposition among the officials and from the imperial government. The following document concerning Christianity was written by the scholar and official Yang Guangxian (1597-1669) and is part of a series of essays denouncing Christianity written between 1659 and 1665. [Source: Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 151-152, Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

In “I Cannot Do Otherwise (Budeyi)”, Yang Guangxian wrote: “[The Jesuit Father] M. Ricci wished to honor Jesus as the Lord of Heaven (Tianzhu) who leads the multitude of nations and sages from above, and he particularly honored him by citing references to the Lord-on-High (Shangdi) in the Six Classics of China, quoting passages out of context to prove that Jesus was the Lord of Heaven. He said that the Lord of Heaven was referred to in the ancient classical works as the Lord-on-High, and what we in the west call “the Lord of Heaven” is what the Chinese have spoken of as “the Lord-on-High.” [According to Ricci] the Heaven (Tian) of the blue sky functions as a servant of the Lord-on-High, which is located neither in the east nor in the west, lacks a head or stomach, has no hands or feet, and is unable to be honored. How much less would earthbound land, which a multitude of feet trample and defile, be considered something to be revered? Thus Heaven and Earth are not at all to be revered. Those who argue like this are no more than beasts able to speak a human language.

“Heaven is the great origin of all events, things, and principles. When principles a (li) are established, material.force (qi) comes into existence. Then, in turn, numbers are created and from these numbers, images begin to take form. Heaven is Principle within form, and Principle is Heaven without form. When shape comes in to its utmost form, then Principle appears therein; this is why Heaven is Principle. Heaven contains all events and things, while Principle also contains all events and things and, as a result, when one seeks the origin of things in the Supreme Ultimate (Taiji) it is only what we call Principle. Beyond principle there is no other principle, and beyond Heaven there is no other Heaven [i.e., Lord of Heaven].

See Yang Guangxian, 1597-1669 I Cannot Do Otherwise (Budeyi) [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Differences Between Christianity and Confucianism by Zhang Xingyao (1633-c. 1715)

According to Columbia University: “By the late seventeenth century, Christianity faced growing opposition among the officials and from the imperial government. Nonetheless, the Jesuits had succeeded in making significant converts among eminent Confucians, and there were small circles of elite Christian men who desired not merely to be Christians, but to make Christianity Chinese by exploring the differences and similarities of Christian doctrine and Confucian philosophy. [Source:“An Examination of the Similarities and Differences Between the Lord of Heaven Teaching (Christianity) and the Teaching of the Confucian Scholars” by Zhang Xingyao, 1633-c. 1715, from “Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 153-154, Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

In “An Examination of the Similarities and Differences Between the Lord of Heaven Teaching (Christianity) and the Teaching of the Confucian Scholars”, Zhang Xingyao wrote: “It is clear in the China of my day that the Lord of Heaven (Tianzhu) [of the Western missionaries] is the same as the Lord-on-High (Shangdi) [of Chinese antiquity]. Since the time of the Yellow Emperor (a legendary figure dated from 2697 B.C.), officials worked together to make sacrifices to the Lord-on-High. Thereafter the words in the classics were all there for anyone to see. Thus Xue disseminated the Five Teachings [of paternal rightness, maternal compassion, friendship of an elder brother, respect of a younger brother, and filial piety of a child], and false teachings did not develop. Sagely wisdom throve; social customs were pure and beautiful. How could things have been better?

“From the time the Buddha’s books entered China, a teaching spread that was altogether deviant. The followers of Laozi promoted this teaching, and thereafter the minds of the people in China lost their ability to question anything. People all degenerated into a condition of merely acquiescing in what they were told, and the Buddha said, “In Heaven above and Earth below, I alone am worthy of honor.” The ability to discern the Lord.of.Heaven degenerated, and it became a great and arrogant demon whom mankind no longer studied, followed, and honored. Consequently, the Three Mainstays [of ruler.minister, parent.child, and husbandwife] and the Five Constants [of Humaneness, Rightness, Ritual Decorum, Wisdom, and Trustworthiness] became hated and there was no effort to urge these on mankind. These people have all gone to hell without end and the followers of Confucius are not able to save them, because Confucius can neither reward nor punish nor judge the living and the dead.

See Zhang Xingyao, 1633-c. 1715 An Examination of the Similarities and Differences Between the Lord of Heaven Teaching (Christianity) and the Teaching of the Confucian Scholars afe.easia.columbia.edu

Protestantism Arrives in China

Protestantism was introduced into China in 1807. After the Opium War, missionary activity increased and Christianity became a part of the Chinese culture. For example, T’ai-p’ing-T’ian-Kuo, a great peasant rebellion in the Ging Dynasty, from 1851 to 1864, was under the banner of God and Christianity. By 1949, China had 700,000 Christians. Generally speaking, Catholicism and Protestantism strengthened the sex-negative and repressive attitudes in China at an official level.

In the 19th century, the Western powers encouraged the construction of missions to expand their influence and power over the Chinese. Many early Chinese converts were labeled "rice Christians" because they were attracted more by church wealth than they were by Christian beliefs. Many Christians are found in coastal cities such as Fuzhou. Many of these are descendants of Christian who were converted by European missionaries, who arrived in the area in 19th and 20th centuries. Sun Yat Sen, the leader of China's first modern revolution in 1911, was a Christian convert. In a speech in 1912 he said "the essence" of the revolution "could be found largely in the teachings of the church."

James Hudson Taylor, the Man Credited with Bringing Christianity to China

J. Taylor Hudson in 1865

James Hudson Taylor, a 19th-century missionary, is credited with taking Christianity to mainland China. Born in Barnsley in South Yorkshire England’s in May 1832 in a tiny apartment above his father’s shop, he converted to Christianity at the age of 17 and, after studying medicine in London, left for Shanghai to work as a missionary. He devoted the rest of his life to religion, spending 50 years in China, where he helped convert more than 18,000 Christians and built 600 churches. Nearly 100 years after his death, his charity, now called the Overseas Missionary Fellowship, continues to work in the Far East. [Source: Sarah Rainey, The Telegraph, January 19, 2012]

In recent years Hudson birthplace, Barnsley, has become viewed as a potential pilgrimage site. Sarah Rainey wrote in The Telegraph, ‘several years ago, a group of leaders from the Chinese church came to England on a holy pilgrimage. They had followed in the footsteps of one of Christianity’s great missionaries in the Far East, travelling for days to worship at the hallowed birthplace of their religious teacher. When they reached their destination, the church leaders got down on their knees and prayed. “This truly is a sacred place,” they said. Canterbury Cathedral, perhaps? Westminster Abbey, or Stonehenge? Not quite. It was a branch of Boots. In Barnsley town centre.

The site where Boots stands was once the Hudson Taylor pharmacy and family home. For his followers, the rows of painkillers and meal deals make for a shrine as worthy as Lourdes. And if a new heritage group has its way, the town could soon see thousands more pilgrims worshipping in the aisles. “There are around 70 million Christians in the Far East who owe their religion to Hudson Taylor,” Dr John Foster, a bakery owner in Barnsley who chairs the James Hudson Taylor group, told The Telegraph. “Yet nobody here knows who he was. Tourists from all over the world come to Barnsley to see his birthplace and the response they get is 'James Hudson who???

A heritage trail should change all that, taking in the landmarks that featured in Hudson Taylor’s life — churches, an independent theatre (once a Wesleyan chapel) and, of course, Boots. Foster’s group is planning an exhibition of artefacts from Hudson Taylor’s missionary work in July, as well as mounting 12 blue plaques in a bid to tempt tourists to explore the town. But it might be a while before the Chinese invasion catches on. “We’re not predicting tens of thousands of people — but it will do wonders for tourism. Barnsley needs something to raise its spirits, and if this inspires a pilgrimage then all the better.”

Christianity in China Under the Communists

The Communists have traditionally equated Christianity with imperialism. Mao accused missionaries as being "spiritual aggressors" and kicked an estimated 10,000 foreign Christian workers, more than half of them Americans, out of the country. Churches were turned into public assembly halls, where Communist propaganda performances were held. Church meetings were replaced with ideological study sessions whose purpose was to reform “misguided” thinking.

Christians were forced to bow to Mao. During the Cultural Revolution, priests were beaten up and imprisoned, churches were destroyed by Red Guards or used as grain houses and Bibles were burnt as tomes of superstition. Mao's wife Jiang Qing, reportedly vowed in 1974 to crush the Christian church in "one day."

After the Cultural Revolution, Beijing decreed that all Christians were required to belong government-supervised patriotic associations, forcing them to pray before an altar of the state and pledge allegiance to the Communist Party.

Bibles are not illegal but only the Amity Printing Press in China can print and distribute them. In July 2005, a Chinese protestant pastor and his wife went on trial on charges of “illegal business practices” after being caught with a cache of 200,000 Bibles.

One state-backed Christian leader said that Christians are free to worship and spread their faith as long as they do so privately. He said they should worship in authorized venues and not public places in order to protect the rights of others. “We don’t have religious activities in public places because we don’t want to cause religious disharmony.”

Chinese authorities allow one Protestant seminary per province, as a way to limit the number of pastors and slow the spread of Christianity. Mao ordered the merger of Protestant denominations in China in 1958; while different strands of Protestantism have informally re-emerged since Mao’s death in 1976, they must share a small supply of seminary graduates, and other pastors trained at bible schools operating informally. [Source: New York Times]

Y.T. Wu: Founder of the Three-Self Patriotic Association

Y.T. Wu founded Three-Self Patriotic Movement, an organization used by the Communist Party to control all Protestant churches in China. William Wan wrote in the Washington Post, “To this day, the vast rift caused by Wu’s organization defines China’s churches. Among the booming unregistered churches, he is vilified. Some worshipers call him a Judas who delivered China’s Christian community into the hands of the Communist government and abetted the persecution of hundreds of thousands of Christians. Yet in government-sanctioned congregations, Wu is revered for creating the Three-Self Patriotic Movement in charge of all Protestant churches.[Source: William Wan, Washington Post, September 7, 2014 /]

“Wu was in his 20s when his father began the Three-Self Patriotic Association in the 1950s. China’s Communist leaders had finally won control of the country, expelled all foreign missionaries and set up an atheistic government. At the private urging of China’s premier, Zhou Enlai, and after meetings with Party Chairman Mao Zedong, Y.T. Wu — also known in China by his full name, Wu Yaozong — spearheaded the establishment of a national church that would be free from foreign influence and completely loyal to the new Communist government. /

“The resulting organization took its Three-Self name from its principles of self-governance, self-support and self-propagation of the Gospel. Congregations that submitted to the organization’s authority were allowed to carry on; those that did not were declared enemies of the state. In the ensuing years, thousands of people were arrested and imprisoned, according to church historians, as Christian worshipers, churches and pastors were encouraged to inform on each other. /

“With the late-1960s Cultural Revolution, registration became moot. All religion in China was banned, and even previously state-backed church leaders were sent to labor camps, Y.T. Wu among them. But from that repression emerged a thriving illegal underground church movement, whose growth outpaced that of the government’s Three-Self churches when they were restored in 1979,” the year Wu died. “A bitter rift between China’s official and illegal churches has existed ever since. To this day, many in the underground churches as well as overseas Chinese Christians question the motives of Wu’s father for creating a state church and ask whether he even believed in God.” /

Rehabilitating Y.T. Wu

Y.T. Wu and Mao

In the 2010s, Y.T. Wu’s son, Wu Zongsu, then in his 80s, sued the Chinese government to get Wu’s diaries back in hopes of rehabilitating his image among Chinese Christians who demonized him. William Wan wrote in the Washington Post, Now “in the twilight of his life, the son is spending his final years and a small fortune trying to piece together a more nuanced portrait of his father. The key to that, however, lies in a 40-volume collection of diaries that the younger Wu says he lent to the Communist Party days after his father’s death and has been unable to recover. Wu thinks that if church scholars could access his father’s early writings, they would understand his original vision for China’s churches — a vision he says the Communist Party later twisted to suit its own purposes. [Source: William Wan, Washington Post, September 7, 2014 /]

“From San Francisco, where he now lives, Wu called the lawsuit against China’s government a last-ditch effort that has slim chances of succeeding. “I don’t have much time left, and there is no one after me to do this work,” he said. He is the last remaining heir and has no descendants. “Some call my father a prophet; others say a betrayer. But the truth is he was just a man, a very complicated one.”“ As the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Three-Self association approached, Wu pushed his more favorable view of his father in personal meetings and at academic symposiums. The son said he became disillusioned with Communism in 1989, when Chinese troops opened fire on Tiananmen Square activists. He was teaching at the time at a university in San Francisco and decided to remain there. “I realized then that Christianity and Communism are like fire and water,” he said. “Christianity emphasizes love. Communism emphasizes the life and death struggle of classes.”/

“Wu argues that while his father was flawed, he was an idealist who subscribed to the mistaken belief that Christianity could coexist with the Communist government, rather than be controlled by it. During the Communist revolution, Wu notes, party leaders spoke of many of the same ideals as Christians — equality, people’s rights and values. “My father saw Communism and Christianity as two sides of the same truth — in pursuit of the same goal, a better society.” He said he has spent $100,000 — his and his wife’s life savings — to help a Hong Kong professor collect what remains of his father’s speeches and writings from throughout China. He also wrote a 60-page paper on his father’s beliefs and work that caused ripples of controversy among scholars when it was published four years ago. Based on his father’s writings and his own recollections, the work is surprisingly unsentimental and unsparing in parts. Only the title betrays Wu’s sympathies: “Fallen Flower, Ruthless Waters.” The flower refers to his father, Wu explains, the waters to the party. /

Lin Zhao, the Christian Revolutionary and Her Blood Letters

Ting Guo wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: “On May 31, 1965, 33-year-old Lin Zhao was tried in Shanghai and sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment. She was charged as the lead member of a counter-revolutionary clique that had published an underground journal decrying communist misrule and Mao’s Great Leap Forward, a collectivization campaign that caused an unprecedented famine and claimed at least 36 million lives between 1959 and 1961. “This is a shameful ruling!” Lin Zhao wrote on the back of the verdict the next day, in her own blood. Three years later, she was executed by firing squad under specific instructions from Chairman Mao himself.[Source: Ting Guo, Los Angeles Review of Books, China Channel, May 19, 2019]

“Lin Zhao’s father committed suicide a month after Lin’s arrest, and her mother died a while after her execution. In Shanghai, where I grew up and where Lin was tried, imprisoned and killed, the story (the sort told only in private) goes that Lin’s mother was asked to pay for the bullets that killed her daughter. It is also said (in private) that in the years that followed, at the Bund, the former International Settlement on the Huangpu River, one could see Lin’s mother crying and asking for Lin’s return.

“Throughout Lin’s imprisonment, where she was subjected to extreme torture, she wrote thousands of letters and essays in her own blood. Those letters are now kept at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace at Stanford University. Lin’s story has and continues to touch and change lives. Gan Cui, Lin’s fiancé, spent four months hand-copying Lin’s blood letters when they first became available to Lin’s siblings, her only remaining family. These hand-copied documents later provided the historical and autobiographical material for Hu Jie, the director of the 2004 documentary Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul, who quit his job and used his personal savings to make the documentary.

“Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao’s China” was written by Lian Xi, a professor or world Christianity at Duke Divinity School who decided to write the book watching, Hu Jie’s 2004 film “Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul”. He said “I watched it and was speechless by the extremity of what she endured as a political prisoner. Later I came upon her prison writings, especially her blood letters to her mother, in which she detailed her unbending resistance under the bleakest circumstances imaginable. Reading them, you peer into the boundaries of the human spirit and see its radiance.

Lin was the first person to openly challenge Mao’s authority since 1949. As Lian Xi records in his book, Lin wrote an appeal to the United Nations in 1966 asking to testify in person about her torture and about human rights abuses in China. The UN never received the appeal – none of Lin Zhao’s letters reached beyond the prison walls in her lifetime. Lin Zhao’s choice to write in her own blood was initially a matter of necessity. When she was handcuffed and deprived of writing instruments, the only way for her to write was to poke her own fingers and compose blood-inked protest poems. However, blood writing for her was also an extreme form of protest, which is why she later continued it after pen and paper were returned to her. During her last months in prison, not knowing that her initial 20-year sentence had been secretly changed to the death penalty, she produced a stream of blood letters to her mother to protest her mistreatment in prison and to attest to her Christian faith and her undying hope for freedom.

Book: Blood Letters of a Martyr, a biography of Lin Zhao by Lian Xi

Lin Zhao’s Experience as a Christian Revolutionary

Lian Xi told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “Lin Zhao grew up in a Christian family and went to a mission school, and was fond of the school’s liberal humanitarian spirit. Activism at her school was contained within genteel boundaries and detached from the social realities at the time, and the school even carried a Victorian ethos. This, in part, sheds light on why the infiltration of communism could be so successful among young students. [Source: Ting Guo, Los Angeles Review of Books, China Channel, May 19, 2019]

During the second quarter of the 20th century, many progressive Christians and patriotic students in mission schools were drawn to the communist vision of a liberated and just society. They saw the communists as fighting the same enemy of systemic evil as they were – perhaps more heroically, because they risked their lives. You would come across stories of “red” pastors working for the revolution. Yenching University’s chancellor, Wu Leichuan, called Jesus a “revolutionary” and urged the church to seek the kingdom of God in a “new social order.” Some of those progressive Christians were cured of their radicalism by the bloody turn of events at the time and went back to an otherworldly faith; others like Lin Zhao waded much deeper into the revolution and had to find out for themselves that the communist revolution had no place for them.

The failure of mission schools to quench the utopian thirst of patriotic students in the late 1940s is not surprising. Bound by their reformist visions and their abhorrence of revolutionary violence, mission schools taught students to fulfill their social responsibility by promoting public hygiene, literacy, liberation of women, compassion for the poor, and the like. As civil war raged on, the economy collapsed, and the authoritarian Nationalist rule turned increasingly corrupt and repressive, that kind of Christian reformism often felt like “trying to put out a burning cartload of firewood with a cup of water,” as the Chinese saying goes. To many progressive students, only the Communist revolution promised a complete deliverance from the miseries of a post-dynastic, war-ravaged China. The CCP was very adept at recruiting radical students in mission schools with the help of underground party cells. One of Lin Zhao’s missionary teachers observed at the time that – given the chaos and deprivation – many young students “would welcome a frying pan as escape from the fire, especially a frying pan so full of Utopian promises.”

Lin Zhao apparently inherited the feisty, independent spirit of her mother. The communist movement she joined as a teen also promoted a particular kind of gender equality: women and men were equal cogs in the revolutionary machine. Like men, women would become foot soldiers of the revolution, so there developed a kind of revolutionary feminism, which I think affected Lin Zhao and her writing style during the 1950s. But Lin Zhao’s moral autonomy as well as her sense of self-worth and social responsibility as a woman went beyond revolutionary feminism. They predated her encounter with communism. The mission school she attended – Laura Haygood Memorial School for Girls – cultivated a strong sense of modern Christian womanhood, so that she felt quite free as a woman in her subsequent pursuits, both political and romantic. After her arrest, she was adamant in asserting her rights and dignity as a female political prisoner. Her revulsion against abuse and sexual harassment in prison helped fuel her indignation and harden her resistance.

Image Sources: Map, stele: Wikimedia Commons; 1) Early crosses, Socdigest.com; 2) Bible and Baptism. Open Door.com; 3) House Church, China Aid; 4) Bible distribution. Chinese Protestant Church; 5) House church raid, Peace Hall com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021