RELIGION IN CHINA

Inside a Chinese temple China is a multireligious country, with a vast proportion of the population professing no religion. Some worship ancestors and/or Shens (“kindly spirits”). Many subscribe to more than one of the main religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, several major Protestant religions, and Confucianism. Taoism, as a religion, is considered a genuine indigenous religion of China in the sense that Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism were imported from foreign countries, while Confucianism is taken to be more secularly oriented in doctrine. [Source: Zhonghua Renmin Gonghe Guo, Fang-fu Ruan, M.D., Ph.D., and M.P. Lau, M.D.]

The four major religions and philosophies found in China are: 1) Confucianism, 2) Taoism, 3) Buddhism, and 4) folk religion — can be looked upon as single traditions or components of a broad, nebulous and variable belief system. Confucianism is not a religion, although some have tried to imbue it with rituals and religious qualities, but rather a philosophy and system of ethical conduct that since the fifth century B.C. has guided China's society. Kong Fuzi (Confucius in Latinized form) is honored in China as a great sage of antiquity whose writings promoted peace and harmony and good morals in family life and society in general. Ritualized reverence for one's ancestors, sometimes referred to as ancestor worship, has been a tradition in China since at least the Shang Dynasty (1750-1040 B.C.). [Source: Library of Congress]

As a communist state, the People’s Republic of China is officially atheist. Most Chinese know very little about China's religious past, namely because the government wants it that way to keep religion reigned in. Traditional Chinese religions are often much stronger in Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, and even Vietnam and Korea than they are in much of mainland China, where the Communists had some success stomping out traditional beliefs and many temples and monasteries are still overseen by caretakers, not monks or priests.

The constitution of 1982 provides for freedom of religion and worship; however, the Chinese government controls religious organizations and restricts religious practices. As of 2004, there were five officially recognized religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism. At that time, by one estimate, about 8 percent of the population were Buddhists, 1.4 percent were Muslims, 1.2 percent were Protestants, and less than 1 percent were Catholics. An estimated 300 million to 400 million people out of a population of 1.4 billion practice traditional Chinese religions such as Buddhism and Taoism. A majority of the population does not claim any religious affiliation, or at least that was teh case at one time. Exact numbers and percentages are hard to come by. See Below. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007, New York Times, 2016]

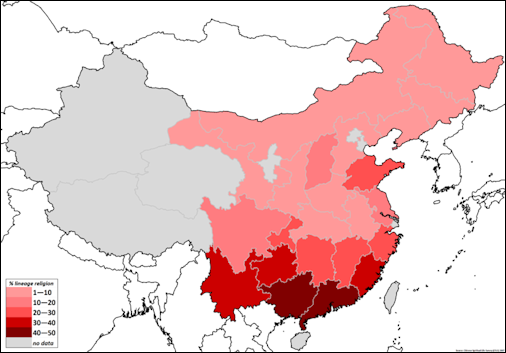

Religion plays a more significant role in daily life in southern China than it does in the north. Many mosques, temples, Taoist shrines, and churches have reopened since the Cultural Revolution, and a great deal of restoration work has been done on ancient Buddhist temples with government money and private donations. Ideology guides artistic expression and social behavior less than it used to, but despite artistic experiments with modern themes and techniques, China remains an austere and authoritarian state. [Source: Cities of the World, Gale Group Inc., 2002, adapted from a December 1996 U.S. State Department report]

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: Traditionally, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and ancestor worship were practiced in an eclectic mixture with varying appeals, and these religions have experienced a revival. Islam, the largest monotheistic sect, is found chiefly in the northwest. There is also a small but growing Christian minority. In recent years there have been some well-publicized confrontations between the Chinese government and religious groups. Places of worship for unregistered Christian churches and traditional sects have at times been destroyed, leaders of such groups have been sentenced to death on apparently trumped-up charges, and orthodox Islamic practices have been discouraged or suppressed out of fear that they would be a focus for Muslim-minority separatists. In 1999 the government banned the Falun Gong (Buddhist Law), a spiritual group with broad appeal that has organized public protests, and began an ongoing campaign to eradicate the religion. There also have been a number of attempts to assert government control over Tibetan Buddhism. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Good Websites and Sources: Chinese Government White Paper on Religion china-embassy.org ; United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religion Facts religionfacts.com; ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy stanford.edu ; Academic Info academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Chinatxt Ancient Chinese History and Religion chinatxt

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN TRADITIONAL CHINAfactsanddetails.com RELIGION AND COMMUNISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; RESTRICTIONS AND REPRESSION ON RELIGION AND REFORM EFFORTS ON CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHRISTIANITY, CHRISTIANS, BIBLES AND HISTORY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; HOUSE CHURCHES AND PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CATHOLICS AND RELATIONS BETWEEN THE VATICAN AND BEIJING factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; SHANG RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors” by C.K. Yang Amazon.com; “The Religion of China” by Max Weber , Hans H. Gerth, et al. Amazon.com; “Religions of China: The World As a Living System” by Daniel L. Overmyer Amazon.com; “The Religions of China: Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism and Christianity” by F. Max Müller Amazon.com; “Religion in China: Ties that Bind” by Adam Yuet Chau Amazon.com ; “Religions of China in Practice” by Donald S. Lopez Jr. | Amazon.com; Amazon.com ; “The Religions of China: Confucianism and Tâoism Described and Compared With Christianity” by Legge James Amazon.com ; “State and Religion in China: Historical and Textual Perspectives” by Professor Anthony C Yu; Amazon.com

Mixture of Religions in China

Mao and the founder of patriotic Chistianity, Y.T. Wu

Eleanor Stanford wrote in “Countries and Their Cultures”: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism are not mutually exclusive, and many people practice elements of all three in addition to worshiping various gods and goddesses, each of which is responsible for a different profession or other aspect of life. Luck is of supreme importance in popular belief, and there are many ways of bringing good fortune and avoiding badluck. A type of geomancy called fengshui involves manipulating one's surroundings in a propitious way. These techniques are used to determine everything from the placement of furniture in a room to the construction of skyscrapers. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“Many of the minority groups have their own religions. Some, such as the Dais in Yunnan and the Zhuangs in the southwest, practice animism. The Uighurs, Kazakhs, and Huis are Muslim. Tibetans follow their own unique form of Buddhism, called Tantric or Lamaistic Buddhism, which incorporates many traditions of the indigenous religion called bon, including prayer flags and prayer wheels and a mystical element.

Many Chinese pragmatically switch among Taoist, Buddhist, folk and other beliefs and practices, depending on the situation. On the ebb and flow and merging of religion in China, Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in Time: “Visions of imperial China as hermetically sealed off from the world are a myth. Foreign belief systems often made their way in and, once reaching Chinese soil, merged with some form of Confucianism (there have been many versions of that creed) or Taoism (ditto) to create hybrid schools of thought. Long before Deng Xiaoping's Marxist-inflected reboot of Lee KuanYew's Singaporean capitalist-meets-Confucian soft authoritarianism, there were equally complex homegrown fusion creations. A famous one was Chan Buddhism (known in Japanese as Zen), a mash-up of native Taoist and imported Indian elements. [Source: Kate Merkel-Hess and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Time, January 1 2011]

Religion Numbers in China

Religion plays a significant part in the life of many Chinese. Estimates of the number of adherents to various beliefs are difficult to establish; as a percentage of the population, institutionalized religions, such as Christianity and Islam, represent only about 4 percent and 2 percent of the population, respectively. In 2005 the Chinese government acknowledged that there were an estimated 100 million adherents to various sects of Buddhism and some 9,500 and 16,000 temples and monasteries, many maintained as cultural landmarks and tourist attractions. The Buddhist Association of China was established in 1953 to oversee officially sanctioned Buddhist activities. Traditional Taoism also is practiced. In 1998 there reportedly were 600 Taoist temples and an unknown number of adherents in China. Official figures indicate there are 20 million Muslims, 5 million Catholics, and 15 million Protestants; unofficial estimates are much higher. By one count there are 67 million Christians. According to to data from the 1990s, 59 percent of the population has no religious affiliation. In the 2000s, it was estimated 20 percent of the people in China practiced traditional religions (Taoism and Confucianism), 12 percent considered themselves atheists, 6 percent were Buddhist, 2 percent were Muslim, and 1 percent were Christian. [Source: Eleanor Stanford, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001; Library of Congress; Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

According to the official website of the State Administration for Religious Affairs, there are currently 33,652 Buddhist temples, 8,269 Taoist venues, about 35,000 mosques, 25,000 Protestant churches and 6,000 Catholic churches in the Chinese mainland for a population of 1.4 billion residents. Taiwan has more than 80,000 religious sites to serve a population of 23 million, Wei Dedong, vice-director of the School of Philosophy at the Renmin University of China, told the Global Times. "Legal religious sites are scarce in China, which may cause some people to resort to extremist religious groups. He pointed out that a great number of unregistered religious sites have emerged due to the insufficiency, citing family gatherings among Christians as an example.[Source: Kou Jie, Global Times January 18, 2016]

For a long time the State Administration for Religious Affairs said there were about 100 million religious believers, about half of which are Christians or Muslims, with the other half Buddhists or Daoists. This is less than 10 percent of China's population. Many Beijing officials admit the real total number of believers is probably much higher than the official estimate of 100 million. There are over 80 million members of the Communist party. In 2009, press releases suddenly began using the number 300 million. China has the potential to be the world's largest Christian nation and the world's largest Islamic nation.

China estimates it has 50 million practitioners of Buddhism and Taoism, 23 million Protestants, 21 million Muslims and 5.5 million Catholics, Independent experts put the number of practitioners of Buddhism, Taoism and folk religions at between 100-300 million. According to the World Christian Database: 1) 41.5 percent non-religious; 2) 27.5 percent Chinese folk believers; 3) 8.5 percent Buddhists; 4) 8.4 percent Christians; 5) 8.2 percent atheists; 6) 4.3 percent animists;7) 1.5 percent Muslims; 8) 0.05 percent other. According to another source: 1) non-religious and atheist, 50 percent; 2) others,32 percent; 3) Buddhists, 9 percent; 4) Christians, 8 percent); 5) Muslims, 2 percent. [Source: World Christian Database; Benjamin Kang Lim and Ben Blanchard, Reuters, September 29, 2013]

According to the U.S. Department of State in 2005, approximately 8 percent of the population is Buddhist, approximately 1.5 percent is Muslim, an estimated 0.4 percent belongs to the government-sponsored “patriotic” Catholic Church, an estimated 0.4 to 0.6 percent belongs to the unofficial Vatican-affiliated Roman Catholic Church, and an estimated 1.2 to 1.5 percent is registered as Protestant. However, both Protestants and Catholics also have large underground communities, possibly numbering as many as 90 million. Chinese government figures from 2004 estimate 20 million adherents of Islam in China, but unofficial estimates suggest a much higher total. Most adherents of Islam are members of the Uygur and Hui nationality people.

Demography of religions in China: Brown: traditional Chinese religion; yellow: Buddhism; dark green: Islam; blue: Mongolian shamanism; purple: ethnic minority religions; light green: religion of the Manchus and northeast China

Religious Demography of China

The U.S. government estimates the total population at 1.35 billion (July 2013 estimate). In its report to the United Nations Human Rights Council during its Universal Periodic Review in October, the government stated there were more than 100 million religious believers, 360,000 clergy, 140,000 places of worship, and 5,500 religious groups. Estimates of the numbers of religious believers vary widely. For example, a 2007 survey conducted by East China Normal University states that 31.4 percent of citizens aged 16 and over, or 300 million people, are religious believers. The same survey estimates that there are 200 million Buddhists, Taoists, or worshippers of folk gods, although accurate estimates are difficult to make because many adherents practice exclusively at home. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, state.gov/|]

According to the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA), there are more than 21 million Muslims in the country; unofficial estimates range as high as 50 million. Hui Muslims are concentrated primarily in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region and Qinghai, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces. Uyghur Muslims live primarily in Xinjiang. According to Xinjiang Statistics Bureau data from 2010, there are approximately 10 million Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Prior to the government's 1999 ban on Falun Gong, a self-described spiritual discipline, it was estimated that there were 70 million adherents. /|\

The 2011 Blue Book of Religions, produced by the Institute of World Religions at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a research institution directly under the State Council, reports the number of Protestants to be between 23 and 40 million. A June 2010 the China government State Administration for Religious Affair (SARA) report estimates there are 16 million Protestants affiliated with the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM), the state-sanctioned umbrella organization for all officially recognized Protestant churches. According to 2012 Pew Research Center estimates, there are 68 million Protestant Christians, of whom 23 million are affiliated with the TSPM. According to SARA, more than six million Catholics worship in sites registered by the Catholic Patriotic Association (CPA). The Pew Center estimates there are nine million Catholics on the mainland, 5.7 million of whom are affiliated with the CPA. /|\

In addition to the five nationally recognized religions, local governments have legalized certain religious communities and practices, such as Orthodox Christianity in Xinjiang, Heilongjiang, Zhejiang, and Guangdong provinces. Some ethnic minorities retain traditional religions, such as Dongba among the Naxi people in Yunnan and Buluotuo among the Zhuang in Guangxi. Worship of the folk deity Mazu has been reclassified as “cultural heritage” rather than religious practice. /|\

Largest religion by province: Brown: traditional Chinese religion; yellow: Buddhism; green: Islam; blue: Mongolian shamanism

Religion, Social Class and Ethnicity in China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Dividing what is clearly too broad a category (Chinese religion or ritual) into two discrete classes (elite and folk) is not without advantages. It is a helpful pedagogical tool for throwing into question some of the egalitarian presuppositions frequently encountered in introductory courses on religion: that, for instance, everyone’s religious options are or should be the same, or that other people’s religious life can be understood (or tried out) without reference to social status. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos ]

“Treating Chinese religion as fundamentally affected by social position also helps scholars to focus on differences in styles of religious practice and interpretation. One way to formulate this view is to say that while all inhabitants of a certain community might take part in a religious procession, their style — both their pattern of practice and their understanding of their actions — will differ according to social position. Well-educated elites tend to view gods in abstract, impersonal terms and to demonstrate restrained respect, but the uneducated tend to view gods as concrete, personal beings before whom fear is appropriate.

“In the social sciences and humanities in general there has been a clear move in the past forty years away from studies of the elite, and scholarship on Chinese religion is beginning to catch up with that trend. More and more studies focus on the religion of the lower classes and on the problems involved in studying the culture of the illiterati in a complex civilization. In all of this, questions of social class (Who participates? Who believes?) and questions of audience (Who writes or performs? For what kind of people?) are paramount.”

“In theory the fifty-five officially recognized ethnic minorities in China are guaranteed the right to practice their culturally distinctive traditions, including the exercise of religion. Often, however, the government asserts that such rights are subsidiary to the need to maintain public order and to register any large social movement. Islam is practiced in China primarily by non-Han ethnic minority groups within China, such as the Uygurs in Xinjiang province. The fact that these Islamic minorities sometimes constitute the majority population of China’s western provinces and autonomous regions (some of which also share a border with other Muslim-majority countries) increases the tendency of the Chinese government to suppress the activities of these Muslim populations and perceive them as a threat to the stability of Chinese governmental control.

“Religious and political activities of Tibetan Buddhists residing in the Chinese autonomous region of Tibet, as well as those residing in neighboring Chinese provinces and regions, are similarly monitored and suppressed by the Chinese government because of the conflict between governmental control, ethnic identity, and religious organization.”

Chinese lineage religion (ancestor worship) in the 2010s

Popular Religion in China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “To define Chinese religion primarily in terms of the three traditions (Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism) is to exclude from serious consideration the ideas and practices that do not fit easily under any of the three labels. Such common rituals as offering incense to the ancestors, conducting funerals, exorcising ghosts, and consulting fortunetellers; the belief in the patterned interaction between light and dark forces or in the ruler’s influence on the natural world; the tendency to construe gods as government officials; and the preference for balancing tranquility and movement — all belong as much to none of the three traditions as they do to one or all three. [Source: adapted from “The Spirits of Chinese Religion,” by Stephen F. Teiser; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

“Popular religion includes those aspects of religious life that are shared by most people, regardless of their affiliation or lack of affiliation with the three teachings. Such forms of popular religion as those named above (offering incense, conducting funerals, and so on) are important to address, although the category of “popular religion” entails its own set of problems. In fact, it is too broad a category to be of much help to detailed understanding — which indeed is why many scholars in the field avoid the term, preferring to deal with more discrete and meaningful units like family religion, mortuary ritual, seasonal festivals, divination, curing, and mythology. “Popular religion” in the sense of common religion also hides potentially significant variation. In addition to being static and timeless, the category prejudices the case against seeing popular religion as a conflict-ridden attempt to impose one particular standard on contending groups.

“The term “popular religion” can be used in two senses. The first refers to the forms of religion practiced by almost all Chinese people, regardless of social and economic standing, level of literacy, region, or explicit religious identification. Popular religion in this sense is the religion shared by people in general, across all social boundaries. Three examples, all of which can be dated as early as the first century CE, help us gain some understanding of what counts as popular religion in this first sense: 1) a typical Chinese funeral and memorial service, including the rites related to care of the spirit in the realm of the dead; 2) the New Year’s festival, which marks a passage not just in the life of the individual and the family, but in the yearly cycle of the cosmos; and 3) the ritual of consulting a spirit medium in the home or in a small temple to solve problems such as sickness in the family, nightmares, possession by a ghost or errant spirit, or some other misfortune.

“The second sense of “popular religion” refers to the religion of the lower classes as opposed to that of the elite. The bifurcation of society into two tiers is hardly a new idea. It began with some of the earliest Chinese theorists of religion. Xunzi, for instance, discusses the emotional, social, and cosmic benefits of carrying out memorial rites. In his opinion, mortuary ritual allows people to balance sadness and longing and to express grief, and it restores the natural order to the world. Different social classes, writes Xunzi, interpret sacrifices differently: “Among gentlemen [junzi], they are taken as the way of humans; among common people [baixing], they are taken as matters involving ghosts.

Folk religion sects' influence by province

Fake Religion in China

The State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA) has collected information on all Buddhist and Taoist temples and sites in China in part to crack down on fake religious practitioners. The China Daily reported: “The initiative follows an incident involving Baima Aose, a self-proclaimed living Buddha, hosting what was purportedly an "enthronement ceremony" to ordain Zhang Tielin, a Chinese actor, in Hong Kong in October 2015. [Source: Xu Wei, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

“Baima Aose resigned from his posts and issued an apology this month after being pronounced a fake by many living Buddhas and by the temple in which he claimed he had been ordained. Master Zongxing, vice-president of the Buddhist Association of China, said the SARA should distinguish in the publicized information between religious venues and registered temples or monasteries.

“Wei Deidong, a professor of Buddhist studies at Renmin University of China, said that the SARA initiative will help the public distinguish between the real and fake. “However, he said, the main reason that many people are still cheated by fake Buddhists and Taoists is that there are not enough temples. "There is not a single Buddhist temple in Beijing's Chaoyang district, which has a population of 2 million," he said. "The key to preventing more cases of clerical charlatanism is to increase the number of real clergy people and real venues."

Religion and Communism

Communism denounces organized religion. Marx called religion the "opiate of the people" and promoted a belief in dialectical materialism over God. Communist countries have traditionally been atheist states, with the Communists attempting to substitute the study of Marxism for religion. Children are encouraged to take part in antireligious activities and schools emphasize antireligious aspects of science. The belief has been that if succeeding generations were taught to reject religion, religion would eventually die out.

Under the Communists many temples, churches and monasteries have been converted into archives of the state, museums, hospitals, schools, and insane asylums. Building a new temple, monastery or church under was the Communists is a problem, not so much because of money, but because is was difficult to secure the necessary building permits. Religion, particularly Christianity and Islam, have traditionally been seen as vehicles for foreign ideas and misguided loyalties to find their way into Chinese society.

In the early years of Communist rule, organized religion was ruthlessly oppressed and infiltrated by informers. Strict limits were placed on what was allowed and what wasn't. Priests were arrested, exiled, killed or forced to renounce their profession. Monks were expelled from their monasteries.

Religious worship retreated into the homes, family groups and small communities. Rituals and ceremonies were performed in secret in back rooms or outdoors on makeshift altars. Religious activists traveling as tourists quietly set up prayer circles in other communities and countries.

Religion and the Chinese Government

China officially recognizes five religions — Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Christianity and Catholicism — and supervises and to varying degrees controls them through state-run associations. The officially atheist government has traditionally been wary of any organization with the potential to challenge its moral authority, especially those with connections to foreigners. Until Communism came along religion and the state were often closely linked. In the imperial era, the emperor was regarded as divine; political institutions were believed to be part of the cosmic order; and Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism were incorporated in different ways into political systems and social organizations.

These days religion is something the officially atheist Communist government tolerates but insists on having control over. The Chinese constitution promises religious freedom but requires that "religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination" and insists that no religious leader have more authority than the Communist party. These views partly explain why the Communists take a such dim view of Chinese Catholics and Tibetan Buddhist holding the Pope and the Dalai Lama in such high esteem.

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: The Chinese Government places restrictions on religious practice outside officially recognized organizations. Only two Christian organizations—a Catholic church without official ties to Rome and the “Three-Self-Patriotic” Protestant church—are sanctioned by the Chinese Government. Unauthorized churches have sprung up in many parts of the country and unofficial religious practice is flourishing. In some regions authorities have tried to control activities of these unregistered churches. In other regions, registered and unregistered groups are treated similarly by authorities and congregations worship in both types of churches. Most Chinese Catholic bishops are recognized by the Pope, and official priests have Vatican approval to administer all the sacraments. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

Religious matters are overseen by the Office of Nationalities, Religion and Overseas Chinese Affairs. According to the U.S. State Department: The Chinese constitution states citizens enjoy “freedom of religious belief” but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities." The government applies this term in a manner that is not consistent with China's international human rights commitments with regard to freedom of religion. In practice, the government restricted religious freedom. The constitution also proclaims the right of citizens to believe in or not believe in any religion. Only religious groups belonging to one of the five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” (Buddhist, Taoist, Muslim, Catholic, and Protestant), however, are permitted to register with the government and legally hold worship services. [Source: “International Religious Freedom Report for 2013 China”, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor, U.S. Department of State, state.gov ]

When making decisions that seem wrong, repressive or unfair to the West on human rights issues China in many ways is acting on lessons it has learned from its long history. It is reluctant to grant too much religious freedom and cracks down on Christians and groups like Falun Gong because of the trouble caused by religion-based rebellions, cults and quasi-religions in the past like the Taipeng Rebellion. See Taiping Rebellion, 19th Century History.

Patriotic Religions and Atheism

Religious institutions in China are required to operate under the control of official “patriotic” religious organizations. There are five officially-recognized “patriotic” religions in China: Protestant Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism and Taoism. Judaism isn't recognized.

Religious activity must be registered with the Religious Affairs Bureau of the State Council and the Communist Party's United Front Work Department. Religions associated with China such as Buddhism and Taoism tend to be tolerated more than Islam and Christianity because they do not have an independent hierarchy or follow a foreign spiritual leader.

Officially Communist China is an atheist country, God does not exist, there is nothing after death and only atheists are allowed to be members of the Communist Party. Mao said that religion is a "base superstition" and a "counter-revolutionary" relic of old China that kept the ruling classes in power. In 1949, after the Communist take over of China, all religions were banned and the Chinese were officially forbidden from talking about ghosts. As late as the early 2000s, the Chinese leader Jiang Zemin expressed his puzzlement that so many Western scientists believe in God.

In many ways Communism has replaced religion. Some have even argued that Communism is a religion. The director of the State Council's Religious Affair Bureau told Time, "The sincere advocacy of freedom of religion belief is based on our understanding of the dialectical materialistic theory. It is our concept of God."

As an alternative to religion, the government has launched the God-free jingshen wenming ("spiritual civilization") program, which teaches values such as family, loyalty and diligence. The atheist party line continues to be promoted by the Research Institute of Marxism-Leninism at the Chinese Academy of Social Science, which continues to give out an annual Hero of Atheism award (the winner in 1999 was a television personality who exposed quack shaman).

Religious Revival After Mao in China

Hundreds of millions of Chinese have turned to religions like Taoism, Buddhism, Christianity and Islam in recent years at least in part to gain a sense of purpose and seek an alternative to China’s consumerist culture. Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: “Religion has blossomed in China despite the Communist Party’s efforts to control and sometimes suppress it, with hundreds of millions embracing the nation’s major faiths — Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and Taoism — over the past few decades. But many Chinese worship outside the government’s official churches, mosques and temples, in unauthorized congregations that the party worries could challenge its authority.[Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 7, 2016]

“Although the governing Communist Party requires its 85 million members to be atheist, its leaders have lauded some aspects of religious life for instilling morality in the broader population and have issueddirectives ratcheting back the hard-line attacks on religion that characterized the Mao era. Over the past decades this has permitted a striking religious renaissance in China, including a construction boom in temples,mosques and churches.

“The decades of reform that started in the late 1970s loosened controls over society, allowing the revival of all religions and many traditions that had been proscribed. Despite periodic crackdowns, churches and mosques, but also temples, were rebuilt, and clergy trained. Although all faiths were supposed to remain under party control, religious feeling boomed, with the number of believers in China topping 500 million by 2010.[Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, December 21, 2019; Johnson is the author of“The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao”]

Beijing Exerts Tighter Grip on Religion During Religious Revival

As new regulations aimed at reigning in religion were put in place in the fall of 2016 by the Chinese government, Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: The finances of religious groups will come under greater scrutiny. Theology students who go overseas could be monitored more closely. And people who rent or provide space to illegal churches may face heavy fines. These are the latest move by President Xi Jinping to strengthen the Communist Party’s control over society and combat foreign influences it considers subversive. The rules, the first changes in more than a decade to regulations on religion, also include restrictions on religious schools and limits on access to foreign religious writings, including on the internet. They were expected to be adopted as early as Friday, at the end of a public comment period, though there was no immediate announcement by the government. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 7, 2016]

“A draft of the new regulations was published in September 2016, several months after Mr. Xi convened a rare leadership conference on religious policy and urged the party to be on guard against foreign efforts to infiltrate China using religion. “It could mean that if you are not part of the government church, then you won’t exist anymore,” said Xiao Yunyang, one of 24 prominent pastors and lawyers who signed a public statement last month criticizing the regulations as vague and potentially harmful.

“The regulations follow the enactment of a law on nongovernmental organizations that increased financial scrutiny of civil society groups and restricted their contact with foreign organizations in a similar way, as well as an aggressive campaign to limit the visibility of churches by tearing down crosses in one eastern province where Christianity has a wide following.

“But the rules on religion also pledge to protect holy sites from commercialization, allow spiritual groups to engage in charitable work and make government oversight more transparent. That suggests Mr. Xi wants closer government supervision of religious life in China but is willing to accept its existence. “There’s been a recognition that religion can be of use, even in a socialist society,” said Thomas Dubois, a professor at the Australian National University in Canberra. “There is an attempt, yes, to carve out the boundaries, but to leave a particular protected space for religion.”

“The new regulations are more explicit about the party’s longstanding requirement that all religious groups register with the government, and the most vocal opposition so far has come from Protestant leaders. “The new rules call for more stringent accounting practices at religious institutions, threaten “those who provide the conditions for illegal religious activities” with fines and confiscation of property, and require the many privately run seminaries in China to submit to state control. Other articles in the regulations restrict contact with religious institutions overseas, which could affect Chinese Catholics studying theology in the Philippines, Protestants attending seminaries in the United States, or Muslims learning at madrasas in Malaysia or Pakistan.

“The regulations also say for the first time that religion must not harm national security, which could give security services in China greater authority to target spiritual groups with ties overseas. Chinese officials have already banned residents from attending somereligious conferences in Hong Kong and increased oversight of mainland programs run by Hong Kong pastors, raising fears within the city’s vibrant Christian community.

Religious Revival Fuels Environmental Activism

Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: China’s “religious revival is helping fuel an environmental awakening. Spiritual leaders are invoking concepts like karma and sin in deriding the excesses of economic development. Religious followers are starting social service organizations to serve as watchdogs against polluters. Advocates are citing their faith to protest plans to build factories and power plants near their homes. “Certainly it is a very powerful force,” said Martin Palmer, the secretary general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation, a group that works with Chinese spiritual leaders. “People are asking, ‘How do you make sense of your life?’ An awful lot are looking for something bigger than themselves, and that is increasingly the environment.” [Source: Javier C. Hernández, New York Times, July 12, 2017]

“The Chinese government, which regulates worship and limits activism, has so far tolerated the rise of religious environmentalists. President Xi Jinping has championed the study of Chinese traditions, including Taoism and Confucianism, in part to counter the influence of Western ideas in Chinese society. Mr. Xi, in articulating the so-called Chinese dream, has called for a return to China’s roots as an “ecological civilization” — a vision he has described as having “clear waters and green mountains” across the land.

“Many spiritual leaders are also energized by what they see as an opportunity for China to become a global leader on environmental issues.“We all live on earth together — we are not isolated,” Abbot Yang Shihua, a Taoist monk, said: “As Taoists, we have to work to influence people in China and overseas to take part in ecological protection.” “Taoist officials have also spoken up at national leadership meetings in recent years, calling on the government to take more action to prevent environmental catastrophes. “The abbot acknowledged that it might seem strange for Taoists, who practice a philosophy of wu wei, or inaction, to be leading a call for change. Still, he said it was important to set an example. “Taoism has almost 2,000 years of history — environmental protection isn’t new for us,” he said. “We have to take action.”

“Environmentalism is infusing other religions in China as well, inspiring Buddhists, Christians and Muslims to take action. In Nanjing, Li Yaodong, 77, a retired government worker and a Buddhist, is the founder of a nonprofit called Mochou, or “free of worries,” dedicated to cleaning up polluted lakes. Mr. Li said that he saw parallels between his faith and protecting the environment. He leads by example, wearing secondhand clothes given to him by his children and collecting used staples to send back to factories. “From an environmental protection perspective, saving means reducing carbon emissions,” he said. “From a Buddhist perspective, it means accumulating merits and doing good deeds.”

“Muslims and Christians are also speaking up on environmental issues. Shen Zhanqing, a pastor who works for the Amity Foundation, a Christian charity, said many church members felt inspired by religion to help protect the environment. The foundation has held study groups on issues like reducing carbon emissions and climate change, and it encourages members to take buses to church. “The decadence of human beings has destroyed the environment in China,” Pastor Shen said. “Our purpose is to protect God’s creation.”

Mao Mountains: an Example of Religion-Driven Environmental Activism

Reporting from Mao Mountain, Javier C. Hernández wrote in the New York Times: Far from the smog-belching power plants of nearby cities, on a hillside covered in solar panels and blossoming magnolias,Yang Shihua speaks of the need for a revolution. Mr. Yang, the abbot of Mao Mountain, a sacred Taoist site in eastern China, has grown frustrated by indifference to a crippling pollution crisis that has left the land barren and the sky a haunting gray. So he has set out to spur action through religion, building a $17.7 million eco-friendly temple and citing 2,000-year-old texts to rail against waste and pollution. “China doesn’t lack money — it lacks a reverence for the environment,” Abbot Yang said. “Our morals are in decline and our beliefs have been lost.”“

“Mao Mountain, with its stretches of untouched land, stands as a monument to nature. Chongxi Wanshou, Abbot Yang’s eco-friendly temple, opened in August 2016. Its 20 acres include an organic vegetable garden. Nearby is a giant statue of Lao-tzu, the founder of Taoism, who is worshiped here as a “green god.” Bees’ nests hang undisturbed, and signs remind passers-by that branches and trees are synonymous with life.

“The mountain’s spiritual leaders say they are seeking to define a distinctly Chinese type of environmentalism, one that emphasizes harmony with nature instead of Western notions of “saving the earth.” Xuan Jing, a Taoist monk with a black beard, said Western notions of the environment were focused on treating symptoms of a problem, not the underlying disease. “You must cure the soul before you can cure the symptoms,” he said. “The root lies with human’s desires.” “Humans follow the earth, the earth follows heaven, heaven follows Taoism, Taoism follows nature.”

“At Mao Mountain, the monks gather each morning to read ancient texts and to write calligraphy next to the trees and stones. Hundreds of visitors climb the stairs each day to pay respect to Lao-tzu. To limit pollution, they are prohibited from burning more than three sticks of incense each. Abbot Yang devotes much of his time to persuading local officials across China to set aside areas for natural protection, an unpopular idea in many parts. He has also worked to attract young, wealthy urbanites to Taoism. Many of them are eager for a spiritual cause and have responded warmly to Taoist leaders’ embrace of environmentalism.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Inside Temple, photo Micheal Turton ; joss sticks, beifan.com

Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021