RELIGION AND COMMUNISM IN CHINA

Communism denounces organized religion. Marx called religion the "opiate of the people" and promoted a belief in dialectical materialism over God. Communist countries have traditionally been atheist states, with the Communists attempting to substitute the study of Marxism for religion. Children are encouraged to take part in antireligious activities and schools emphasize antireligious aspects of science. The belief has been that if succeeding generations were taught to reject religion, religion would eventually die out.

Communism denounces organized religion. Marx called religion the "opiate of the people" and promoted a belief in dialectical materialism over God. Communist countries have traditionally been atheist states, with the Communists attempting to substitute the study of Marxism for religion. Children are encouraged to take part in antireligious activities and schools emphasize antireligious aspects of science. The belief has been that if succeeding generations were taught to reject religion, religion would eventually die out.

Under the Communists in China many temples, churches and monasteries have been converted into archives of the state, museums, hospitals, schools, and insane asylums. Building a new temple, monastery or church under was the Communists is a problem, not so much because of money, but because is was difficult to secure the necessary building permits. Religion, particularly Christianity and Islam, have traditionally been seen as vehicles for foreign ideas and misguided loyalties to find their way into Chinese society.

In the early years of Communist rule, organized religion was ruthlessly oppressed and infiltrated by informers. Strict limits were placed on what was allowed and what wasn't. Priests were arrested, exiled, killed or forced to renounce their profession. Monks were expelled from their monasteries.

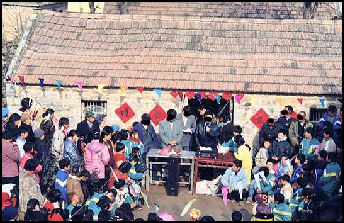

Religious worship retreated into the homes, family groups and small communities. Rituals and ceremonies were performed in secret in back rooms or outdoors on makeshift altars. Religious activists traveling as tourists quietly set up prayer circles in other communities and countries.

Good Websites and Sources: Chinese Government White Paper on Religion china-embassy.org ; United States Commission on International Religious Freedom uscirf.gov/countries/china; Articles on Religion in China forum18.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religion Facts religionfacts.com; ; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy stanford.edu ; Academic Info academicinfo.net ; Internet Guide to Chinese Studies sino.uni-heidelberg.de; Chinatxt Ancient Chinese History and Religion chinatxt ; History Websites: 1) Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia Links in this Website: Main China Page factsanddetails.com/china (Click History)

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CONFUCIANISM factsanddetails.com; CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com; TAOISM factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION, SUPERSTITION, FUNERALS factsanddetails.com; RELIGION IN TRADITIONAL CHINAfactsanddetails.com CHRISTIANITY, CHRISTIANS, BIBLES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; HOUSE CHURCHES AND PERSECUTION OF CHRISTIANS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE CATHOLICS AND RELATIONS BETWEEN THE VATICAN AND BEIJING factsanddetails.com; FOLK RELIGION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; MUSLIMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JEWS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; SHANG RELIGION AND BURIAL CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Religion under the Communist Regime

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Since the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, freedom of religion, as well as freedom to propagate atheism, has been guaranteed in the Chinese Constitution. Yet the Communist party has consistently maintained a negative attitude; active suppression was greatest during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and more recently has considerably abated. [Source: adapted from “Religion in a State Society: China,” by Myron L. Cohen ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos ]

Cultural-Revolution-era book critcizing Confucius

“Although diffuse (or popular) religion (see Notes, below) played a much larger role in daily life than did institutional forms, the government now only grants official recognition as religious groups to the major organized churches of Islam, the two major denominations of Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism), Daoism, and Buddhism. All but the last two had been significant for only a minority of the population, and institutional Buddhism and Daoism had only a specialized and limited role in the religious life of most people.

“Under the Communists, the number of believers affiliated at least publicly with the institutional religions had decreased significantly, but in the more permissive atmosphere of recent times, especially since the several national religious associations were reactivated in1979, Buddhism and both denominations of Christianity in particular have shown signs of revival.

“Pressure against popular religion, considered to be “feudal superstition,” has always been greatest, and even to the present this religious system continues to be most disfavored. Since popular beliefs constituted a religious framework for traditional social organization, they were viewed by the Communists as a major obstacle to the goal of radical reorganization. The Communist attack on popular religion thus was greatest during the periods of land reform (1950-1954) and collectivization (1954-1979), for popular religion reinforced traditional social alignments by emphasizing community solidarity and autonomy, values the Communists wished to replace with class consciousness and the integration of collectivized communities into a socialist economy and polity.

“Thus, while popular religion as a whole was denounced and suppressed, community religion came under the strongest attack. Throughout China village temples, local Earth God shrines, ancestral halls and other such structures were dismantled or converted to nonreligious uses. Important elements of popular religion have survived, however, to varying degrees in different parts of the country.

“During periods of greater repression, almost all such religious practices were carried out within the family, thus offering testimony to the continuing vitality and autonomy of family organization. Ancestor worship remains widespread, especially in the countryside, although even today it is sometimes practiced covertly: in some villages the objects of worship are tablets, scrolls or photographs kept at home; in others, tablets destroyed during the Cultural Revolution have not been replaced, but the rituals of ancestor worship are maintained. The joint worship by several families of a common ancestor is practiced far less frequently, for this involves organization above the family level. Within the family there continues the worship of other gods and spirits, at least in some parts of the country. It is not surprising that funerals appear to have consistently retained more of their religious content than other rituals. This presumably reflects concerns about mortality that cannot be satisfied by more contemporary world-views.

Notes: The sociologist C. K. Yang first coined the term “diffused religion” to describe religious beliefs and practices expressed in family and community contexts rather than within an organized or institutional religion framework, in his “Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961).”

History of Religion in China Since the Communists Came to Power

Traditionally, China's Confucian elite disparaged religion and religious practitioners, and the state suppressed or controlled organized religious groups. The social status of Buddhist monks and Taoist priests was low, and ordinary people did not generally look up to them as models. In the past, religion was diffused throughout the society, a matter as much of practice as of belief, and had a weak institutional structure. Essentially the same pattern continues in contemporary society, except that the ruling elite is even less religious and there are even fewer religious practitioners. [Source: Library of Congress *]

“The attitude of the Communist Party has been that religion is a relic of the past, evidence of prescientific thinking, and something that will fade away as people become educated and acquire a scientific view of the world. On the whole, religion has not been a major issue. Cadres and party members, in ways very similar to those of Confucian elites, tend to regard many religious practitioners as charlatans out to take advantage of credulous people, who need protection. In the 1950s many Buddhist monks were returned to secular life, and monasteries and temples lost their lands in the land reform. Foreign missionaries were expelled, often after being accused of spying, and Chinese Christians, who made up only a very small proportion of the population, were the objects of suspicion because of their foreign contacts. *

“Chinese Christian organizations were established, one for Protestants and one for Roman Catholics, which stressed that their members were loyal to the state and party. Seminaries were established to train "patriotic" Chinese clergy, and the Chinese Catholic Church rejected the authority of the Vatican, ordaining its own priests and installing its own bishops. The issue in all cases, whether involving Christians, Buddhists, or members of underground Chinese sects, was not so much doctrine or theology as recognition of the primacy of loyalty to the state and party. Folk religion was dismissed as superstition. Temples were for the most part converted to other uses, and public celebration of communal festivals stopped, but the state did not put much energy into suppressing folk religion. *

“During the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, in 1966 and 1967, Red Guards destroyed temples, statues, and domestic ancestral tablets as part of their violent assault on the "four olds" (old ideas, culture, customs, and habits). Public observances of ritual essentially halted during the Cultural Revolution decade. After 1978, the year marking the return to power of the Deng Xiaoping reformers, the party and state were more tolerant of the public expression of religion as long as it remained within carefully defined limits. Some showcase temples were restored and opened as historical sites, and some Buddhist and even Taoist practitioners were permitted to wear their robes, train a few successors, and perform rituals in the reopened temples. These actions on the part of the state can be interpreted as a confident regime's recognition of China's traditional past, in the same way that the shrine at the home of Confucius in Shandong Province has been refurbished and opened to the public. Confucian and Buddhist doctrines are not seen as a threat, and the motive is primarily one of nationalistic identification with China's past civilization. *

Mao and the Dalai Lama in 1954

Similar tolerance and even mild encouragement is accorded to Chinese Christians, whose churches were reopened starting in the late 1970s. As of 1987 missionaries were not permitted in China, and some Chinese Catholic clergy were imprisoned for refusing to recognize the authority of China's "patriotic" Catholic Church and its bishops. The most important result of state toleration of religion has been improved relations with China's Islamic and Tibetan Buddhist minority populations. State patronage of Islam and Buddhism also plays a part in China's foreign relations. *

“Much of traditional ritual and religion survives or has been revived, especially in the countryside. In the mid-1980s the official press condemned such activities as wasteful and reminded rural party members that they should neither participate in nor lead such events, but it did not make the subject a major issue. Families could worship their ancestors or traditional gods in the privacy of their homes but had to make all ritual paraphernalia (incense sticks, ancestral tablets, and so forth) themselves, as it was no longer sold in shops. The scale of public celebrations was muted, and full-time professional clergy played no role. Folk religious festivals were revived in some localities, and there was occasional rebuilding of temples and ancestral halls. In rural areas, funerals were the ritual having the least change, although observances were carried out only by family members and kin, with no professional clergy in attendance. Such modest, mostly household-based folk religious activity was largely irrelevant to the concerns of the authorities, who ignored or tolerated it. *

Early Communist Persecution of Buddhists in China

In the Mao era Buddhist temples become schools and warehouses and monks were rounded up and imprisoned and, in some cases, executed. Master Deng Kuan, abbot of the Gu Temple in Sichuan Province, was 103 when the writer Liao Yiwu met him in 2003. “Over the centuries, as old dynasties collapsed and new ones came into being, the temple remainedrelatively intact," Deng told Lao, “This is because changes of dynasty or government were considered secular affairs. Monks like me didn't get involved. But the Communist revolution in 1949 was a turning point for me and the temple."[Source: The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up by Liao Yiwu, from book review by Howard W. French in The Nation, August 4, 2008 ]

“Soon after Mao's victory, Deng was dragged out of his temple and stood up before a crowd, accused of accumulating wealth without engaging in physical labor, and spreading “feudalistic and religious ideas that poisoned people's minds." People stepped forward to denounce him, and the crowd that gathered responded on cue, howling slogans like “Down with the evil landlord” and “Religion is spiritual poison." Some spat on him. Others punched and kicked. “No matter which temple you go to, you will find the same rule: monks pass on the Buddhist treasures from one generation to the next," Deng says. ‘since ancient times, no abbot, monk, or nun has ever claimed the properties of the temple as his or her own. Who would have thought that overnight all of us would be classified as rich landowners! None of us has ever lived the life of a rich landowner, but we certainly suffered the retribution accorded one."

“By Master Deng's reckoning, between 1952 and 1961 this meant he endured more than 300 ‘struggle sessions," as these organized hazings were known in the revolution's euphemistic terminology. In his area of Sichuan Province, he tells Liao, by 1961 “half of the people labeled as members of the bad elements had starved to death."

Crackdown on Religion in the Cultural Revolution

Cultural Revolution damage to Buddhist statues in Gansu

During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards did not discriminate against particular religions, they were against them all. They ripped crosses from church steeples, forced Catholic priests into labor camps, tortured Buddhist monks in Tibet and turned Muslim schools into pig slaughterhouses. Taoists, Buddhists and Confucians were singled out as vestiges of the Old China that need to be changed.

One Chinese man told Theroux about an effort by the Red Guard to tear down a cross from the largest church in Qindao: "The Red Guards held a meeting, and then they passed a motion to destroy the crosses. They marched to the church and climbed up to the roof. They pulled up bamboos and tied them into a scaffold. It took a few days “naturally they worked at night and they sang the Mao songs. When the crowd gathered they put up ladders and they climbed up and threw a rope around the Christian crosses and they pulled them down. It was very exciting!"

In Tibet the Red Guard turned thousand-year-old monasteries into factories and pigsties. "When the order went out, Smash the feudalistic nests of monks!," Paul Theroux wrote, "the soldiers, Red Guards and assorted vandals made chalk marks all over the monasteries’save these timbers, stack these beams, pike the bricks, and so forth. Brick by brick, timber by timber, the monasteries were taken down. The frugal, strong-saving, clothes-patching, shoe-mending Chinese saved each reusable brick. In this way the monasteries were made into barns and barracks."

Religion in the Deng Era

“In 1978, a ban on religious teaching that dated from early in the revolution was lifted, and a few years later the rebuilding of the Gu Temple, and hundreds of others around China, got under way in earnest, aided by donations from people who had kept their faith in secret. No longer the target of punishing political campaigns, Master Deng has other worries: the designs of predatory local officials who see temples like his as cash cows or comfortable digs for their gambling parties. “A couple of months ago, some officials showed up and set up their mah-jongg tables right inside the temple," he says." [Source: The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up by Liao Yiwu, from book review by Howard W. French in The Nation, August 4, 2008]

They played that gambling game all day. Some ended up losing money. They walked into my room and wanted to get a loan from me. I did “lend” some to them. You know they will never pay back... The officials are so powerful, and can destroy you at a whim. The chief of the Religious Affairs Bureau shamelessly calls himself the parent of all gods.

Religion in China Today

Taoist ceremony in Guangdong

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In the 1970s it was commonly asserted that “Chinese religion,” at least as it had existed during Qing dynasty times, had ceased to exist altogether. But something rather curious occurred between the 1970s to the late 1990s and the present. If one goes to China today one can see local temples blossoming and being reconstructed at a rapid rate. Periodically there is another crackdown on religious activity, but it would certainly appear that religion in China today, which is clearly derivative of traditional Chinese religion, with certain modern additions, has come back with increasing force. For example, the farmer’s almanac, which helps one determine auspicious days for conducting various life events such as building a house or getting married, is once again being widely printed and used in China today. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia ]

“As well the practice of fengshui, a form of geomantic divination based on the workings of yinyang and qi, is on the rise. And some would even assert that Mao Zedong (1893-1976) himself has been made a god among the people. Indeed, in what is in a sense an ironic commentary on both Mao and the power of traditionally derived beliefs, the Communist leadership made the decision to place Mao’s mausoleum in the middle of Tiananmen Square on the erstwhile site of the Gate of China (Zhonghuamen), which was the southern gate of the old Imperial City and aligned with the central axis of Beijing.

“Still, Chinese religion as it was under the Qing dynasty clearly is not coming back. We can say, however, that contemporary Chinese religion is being reinvigorated, and this new religion has its roots in the religious patterns of late-imperial times. What we see today is late-imperial religion with adaptations to present day circumstances and all the history that has transpired between the end of the Qing dynasty until today.”

Religion and the Chinese Government in the 2000s

In December 2004, the Chinese government announced new rules that guarantee religious beliefs as a human right. According to an article in The People's Daily: “As China has more than 100 million people believing in religion, so the protection of religious freedom is important in safeguarding people's interests and respecting and protecting human rights." Some have their doubts as to whether this announcement means anything. A Finnish evangelist who has worked in China for a long time told Time, "There are two words that define China's attitude towards religious freedom: control and stability."

Land reform laws permit monasteries and temple to keep much of their land. Traditionally city monasteries and temples were required to engage in light industry and monks were required to produce a certain amount of crops on the land. If they didn't they risked losing the land. Some of these rules have been relaxed.

In March 2005, religion was enshrined in China as a basic right of all citizens. Even so worship outside designated religion remains forbidden. The Chinese government has been criticized by the U.S. State Department for suppressing and denying religious freedom to Christians, Tibetan Buddhists, Uighurs and members of Falun Gong.

In April 2006, a leader of China's state-backed Christian church — the Rev. Cao Shengjie, president of the China Christian Council’said that believers were free to worship within limits, namely that they worship in private and “don't have religious activities in public places because we don't want to cause religious disharmony."

House church In December 2007, Chinese President Hu Jintao appeared to give a tacit endorsement to religion by hosting a politburo study session on the expanded role of religion, and allowing religion to be discussed at the 17th Party Congress in October the same year. In January 2008, a photograph of Hu shaking hands with one of China's main Christian leaders was featured prominently on the front page of the People's Daily, the official Communist Party newspaper. .

In a speech at the study session Hu said, “We must strive to closely unite religious figures and believers among the masses around the party and government and struggle together with them to build an all-around moderately prosperous society while quickening the pace towards the modernization of socialism." The overall message seemed to be that religion is something that can be harnessed for economic and social progress but are nor necessarily things that should be pursed in themselves.

The phrase “parent of all gods” entered the news during the crisis in Tibet, when the “autonomous region's” party secretary declared that the Communist Party was the “real Buddha” for Tibetans.

Religious Revival in China

After Mao died, the government loosened up on religion. It stated it made a mistake persecuting monks and nuns during the Cultural Revolution and quietly abandoned many of its atheist positions. Under these circumstances, religion has experienced a rebirth. Buddhist, Taoism, and Muslim religious centers have reopened; lots lot of time and money has gone into building temples; and superstition and folk religion have crept back in people's lives.

Interest in religion is growing. In survey by two professors at Shanghai's East China Normal University 31 percent of the 4,500 people interviewed described themselves as religious. If that figure is representative for the whole country then 400 million Chinese regard themselves as religious, four times the official government number of 100 million. Most of those who described themselves as religious said they were Buddhists, Taoists or followers of folk religions. Religious beliefs were found to be particularly strong among people in the 16-to-39 age group. Among those most interested in religion are China's wealthier classes. Members of the Communist Party are still banned from belonging to a formal religion.

Evangelical Christian gathering

In Yulin, a city of about 1 million people in northern Shaanxi, 50 major temples, 500 medium-size temples and thousands of smaller temples have been built or repaired since Mao's death in 1976. A school teacher there took it upon himself to rebuild a temple honoring a maiden who got pregnant by eating a peach and gave birth to five dragons — black, red, white, green and yellow — through her nostrils, mouth and ears.

Ancestor worship, Buddhism, Christianity and devotion to local gods has returned in a big way in southern Chinese. Ancestor worship halls have sprung up in Guandong; Buddhist monks advertise on television in Fujian; shaman and yingyang masters have set up enterprises in rural communities; and Bibles are being printed up by the millions.

On his experiences entering houses in Shanghai's oldest neighborhoods, Howard French wrote: “I had not expected to find so much evidence of China's thriving quasi-underground religious culture here. In house after house, I found people worshiping privately as Christians or Buddhists. Asked how she had come to the church, a woman who had been sent to the countryside as a youth in the Cultural Revolution told me she had been converted by her neighbors. Everyone in this building believes in Christ, she said." [Source: Howard W. French, New York Times, August 28, 2009]

As the interest in religion has grown a multitude of quack healers, self-proclaimed prophets and spiritual masters have appeared. Scholars have compared the Chinese to passengers on a rudderless boat drifting a sea. Every time the wind shifts they look for new direction and easily manipulated because they feel have nothing to lose.

In many cases the government views the revival as a threat but can do little to stop it because the movement is so widespread. One Chinese sociologist told Newsday, “The resurgence of folk religions reflects the pursuit of folk symbols of authority and new ways of communicating. It represents the rise of a new kind of rural power and authority." Perhaps the biggest obstacle that religion has to overcomes is money as it battles materialism for attention and the hearts and souls of many Chinese.

Reasons for Religious Revival in China

Religion addresses many questions that Communism doesn't answer and there sometimes seem to be a need in China to address these questions. American sociologist William T. Liu told Time, "Chinese communism is a system of economic development, but there is no theology to explain what people should believe in." Chinese that once believed in the Communist Party with religious zeal have lost faith partly as result of its widespread corruption and are looking to fill the void.

Many feel that China is experiencing a spiritual vacuum. Li Baiguang, a prominent lawyer and Chinese activist, told the Times of London, “Rising wealth means that more and more people have been able to meet their material needs, the need for food and clothing. Then they are finding that they need to satisfy their spiritual needs, to look for happiness for the soul. In addition, they are seeing a breakdown on the moral order as money tales over."

Buddhism and Christianity have become especially popular with new believers who come fall all segments of society, rich and poor, urban and rural. On religion and materialism, Aloysius Jin Luxian, Shanghai's 92-year-old bishop who spent 27 years in labor camps and prison, said, ‘souls become ever more empty, which affords religion room to expand."

Chinese President Hu Jintao has repeatedly said there is place for spirituality religion in modern Chinese society, in part to fill the void left by the collapse of Communist ideology. But rather than being more accepting of existing religions he has attempted to steer Chinese towards traditional Marxist values and traditionally Confucian beliefs about society.

Reemergence of Popular Religion and Chinese Identity

Spirit tablets of Qing Emperors

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The contemporary reemergence of religion in China is quite revealing, for it makes it clear, in retrospect, that religion was never completely destroyed. Even at the height of the Cultural Revolution, which was fiercely anti-traditional, only the physical evidence of religion — not religious practice itself — was destroyed. Ancestral tablets and the images of the gods were destroyed, sometimes by Red Guards and sometimes by people who kept the objects but feared discovery by the Red Guards. But all this did not stop traditional religious practices altogether. In fact, they continued widely, though only within the family. Thus, the reemergence of religion can be understood as something coming out of hiding rather than something that disappeared altogether and is now being resurrected. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/cosmos ]

“But there is a major issue here yet to be resolved. How can these revised traditional beliefs be related to some sense of Chinese nationhood, of a unified Chinese culture and of a Chinese cultural presence? In the late-imperial period the notion of being “Chinese” was intimately involved with the notion of being in a cosmos of which China was the central part. One of the ironies of the anti-traditionalism associated with the first wave of elite Chinese nationalism was that the nationalists were attacking a traditional source of Chinese identity by attempting to destroy a major cultural framework within which people saw themselves as being “Chinese.” At the same time, the nationalists saw themselves as being strongly “Chinese” and were ardent supporters of Chinese strength against foreign aggression. The issue today is of how a contemporary sense of Chinese national identity will or will not relate to some of these earlier traditions. That issue is one that is very much in the air in Chinese culture and society today.

Search for Spirituality and Meaning in Modern in China

Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote in the New York Times, “As people search for happiness and freedom, spiritual traditions are flourishing, including Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism and folk religions, as well as Christianity and even Bahai. But according to Robert N. Bellah, one of the world's foremost sociologists of religion and author of “Religion in Human Evolution, to establish true freedom through a society wide, ethical framework that is connected to Chinese traditions, the country first must break the tyrannical spell cast by Mao Zedong, who led the Communists to victory in the civil war in 1949 and ruled with an iron fist until his death in 1976. [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times December 28, 2011 ]

“Bellah notes the parallels between Mao and Qin Shihuangdi, a follower of the Legalist philosophy, which taught that only harsh punishments could keep people in line and provide effective government. The Qin emperor silenced criticism, burned books and buried scholars alive, while Mao, who admired the emperor, once boasted that he had caused the death of more scholars than Qin Shihuangdi. Qin Shihuangdi's short-lived reign proved that tyranny doesn't work, Mr. Bellah writes in “Religion in Human Evolution." ‘somehow a moral basis of rule was necessary after all," he wrote. What, then, might China's “moral basis” look like, as the country looks to the future as an increasingly important member of the world community” Mr. Bellah offered the traditional Chinese concepts of tian, or heaven; li, manners or rituals; and yi, justice, as some building blocks of morality.

“Bellah, 84 in 2011, published “Religion in Human Evolution” in 2011. The book traces the roots of belief and ethics in human society and examines four cultures — Israel, Greece, China and India — from 800 B.C. to 200 B.C., when major world philosophies were formed. “Turning away from Legalism and Mao is going to be a challenge, because they haven't worked their way through the Mao period," said Mr. Bellah, a sociology professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. “His picture is still there, and they want to separate the good from the bad part of Mao Thought. Well, sorry, you can’t. You've got to break the spell," said Mr. Bellah.

“Mr. Bellah said he was deeply impressed by the forward-looking optimism and — relatively — free debate he saw in China among intellectuals and students. Yet people also seem to be morally adrift, with the “eviscerated” Marxism of the Communist Party failing to provide the framework for a functioning set of beliefs, Mr. Bellah said. Chinese leaders, who are officially atheist, assume that they have a moral system in place already, he said. “The fact that Marx is taught at every level, from kindergarten to university, shows that they think they have a civil religion. The fact that to many Chinese it's a joke and they don't take it seriously shows they have a problem on their hands." I think China has to face the fact that Mao was a monster, one of the worst people in human history," said Mr. Bellah.

“He compared China's situation today to that of Germany and Japan after World War II. “In a curious way, it's like the war guilt of Germany or Japan. I think in Germany they've come to terms with it, whereas in Japan there's almost a dramatic lack of any sense of responsibility," said Mr. Bellah, who is also a Japan scholar. “There is so much self-pity in China about the Western powers and the 150 years of imperialism, and about the Japanese aggression” of World War II, said Mr. Bellah. “And it's justified in a way." “But God knows what Mao did can't be blamed on the Westerners or the Japanese," he said. “The Chinese have their own guilt, and it requires a complex symbolic, ideological and psychological change, and that's hard."

“Why do morals matter? Because tyranny does not work. Qin Shihuangdi's short-lived reign proved that, Mr. Bellah writes in “Religion in Human Evolution." ‘somehow a moral basis of rule was necessary after all," he wrote. What, then, might China's “moral basis” look like, as the country looks to the future as an increasingly important member of the world community? Mr. Bellah offered the traditional Chinese concepts of tian, or heaven; li, manners or rituals; and yi, justice, as some building blocks of morality.

“The emphasis in his book on Chinese tradition as a contemporary guide was warmly welcomed in a recent essay in the state-run newspaper China Daily, in which the writer, Zhang Zhouxiang, argued, perhaps pointedly, that li justifies the ruler's right to rule but that the ruler also has an obligation to treat his subjects well. “The ruled are asked to maintain order, but they also have the right to choose another ruler if the covenant is broken," Mr. Zhang wrote.

“Importantly, the Confucian tradition of individual self-improvement also provides “a moral resource, no question," said Mr. Bellah. “In this way, China is deeply egalitarian. I think there are great moral resources in China for moving ahead in good directions, but you can't predict these things," he said, noting that the Communist Party relies on people's fear of social chaos to justify its controls. “But there's a certain point at which that argument isn't enough," he said. “You need something more substantial than that." True ethical standards — in fact, a new civil religion — must develop “if China is to fulfill its ability to be one of the great powers of the 21st century," Mr. Bellah said.”

Are China's Rulers Getting Religion?

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books, “With worsening inflation, a slowing economy, and growing concerns about possible social unrest, China's leaders have a lot on their plates these days. And yet when the Communist Party met at its annual plenum earlier this week, the issue given greatest attention was not economic policy but what it described as “cultural reform." [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, November 10 2011 -]

“The concern appears quixotic, but China is now in the grips of a moral crisis. In recent months, the Chinese Internet has been full of talk about the lack of morality in society. And the problem is not just associated with the very rich or the political connected — concerns shared in western countries — but with the population at large. This has been precipitated in part by a spate of recent incidents in which people have failed to come to aid of fellow citizens caught in accidents or medical emergencies. A few weeks ago, a two-year-old girl in Guangzhou was hit by a car and left dying in the street while eighteen passers-by did nothing to help her. The case riveted China, causing people to ask what sort of society is being created. -

“So, no sooner was the plenum over than the party indicated that it would limit the amount of entertainment shows on television and possibly set limits on popular microblogs. While it is easy to read this move simply as censorship, which it certainly is, it also reflects the new preoccupation with morality: many of the banned shows are pure entertainment — the party now wants more news programs — and Chinese microblogs have long been a forum for anonymous character assassination. Meanwhile, though it has been far less noted, Beijing is giving new support to religion — even the country's own beleaguered traditional practice, Daoism. -

“After decades of destruction, Daoist temples are being rebuilt, often with government support. Shortly after the plenum ended, authorities were convening an International Daoism Forum. The meeting was held near Mt. Heng in Hunan Province, one of Daoism's five holy mountains, and was attended by 500 participants. It received extensive play in the Chinese media, with a noted British Daoist scholar, Martin Palmer, getting airtime on Chinese television. This is a sharp change for a religion that that was persecuted under Mao and long regarded as suspect.” -

Religion in the Xi Jinping Era

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: There is a “new civil religion taking shape in China — an effort by the Chinese Communist Party to satisfy Chinese people’s search for moral guidelines by supplementing the largely irrelevant ideology of communism with a curated version of the past. This new state-guided religiosity is the flip side of the government’s harsh policies toward Islam and Christianity. Officials believe these two global faiths are hard to control because of their foreign ties, and they have used negotiation or force — diplomacy with the Vatican, arrests of prominent Protestants, internment camps for Muslims — to try to bring these religions to heel. Yet Beijing’s recent turn to tradition may be even more significant. Even though Islam and Christianity are world religions, in China they remain minor, with the number of their combined adherents amounting to less than 10 percent of the population. Most Chinese believe in an amalgam of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism and other traditional values and ideas that still resonate deeply. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, December 21, 2019; Johnson is the author of“The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao”]

“For this silent majority of hundreds of millions of people, the government’s newfound support for things like the temple to Lord Guan is welcome — a feeling that the Chinese Communist Party hopes will bolster its legitimacy, especially given the irrelevance today of its founding ideas. The benefits of its move to embrace the past may seem obvious, but the shift marks a radical departure, not just for a party officially committed to atheism but also from how reformers over the past century have imagined a modern, prosperous China.

“Xi Jinping’s rise to power in late 2012 marks a new era, the third, in the history of the Chinese Communist Party’s religious policies. Instead of the destruction of the Mao years and the relatively laissez-faire approach of the reform period, the state has embarked on a form of highly curated revivalism. One part of its approach rests on a deep suspicion of Christianity and Islam. The party’s policy toward Islam has been the most draconian. Some believers, especially Uighurs in the northwestern province of Xinjiang, have been subjected to a policy of forced secularization. This has included sending hundreds of thousands of Muslims to re-education camps, compelling restaurants to serve pork and alcohol, and forbidding fasting during Ramadan.

“The policy toward Christianity is more nuanced. Last year, Beijing struck a deal with the Vatican to jointly appoint Catholic bishops. The Vatican seemed to hope to reverse the decline in the number of Catholics in China. But for Beijing, the measure was a way to tighten control over the Catholic clergy — and, by extension, the church itself. Protestantism poses an especially vexing problem for the party. It is arguably China’s fastest-growing religion, with an estimated 60 million or more adherents today (compared with one million in 1949), including some 20 to 30 million who are thought to worship in unregistered (or underground) Protestant churches. But the faith lacks a unifying structure that would allow for negotiations. And so the government has fired a few shots across the bow, closing several of the country’s best-known underground churches.

“In many ways, however, the Xi administration’s embrace of traditional faiths is more radical. Since taking office, the president has met with Buddhist leaders, and his government has allowed Taoism to flourish. The state recently issued a landmark plan to improve social mores, the first such program since 2001. The plan stems from a widespread feeling that China’s relentless drive to get ahead economically has created a spiritual vacuum, and sometimes justifies breaking rules and trampling civility. Many people do not trust one another. The government’s blueprint for handling this moral crisis calls for endorsing certain traditional beliefs.

“The epic paper — it runs to 10,000 Chinese characters, and would be significantly longer translated into English — doesn’t mention Communist China’s founding father, Mao Zedong, or his successors and their ideologies, focusing instead on Mr. Xi and his efforts to fix social problems like “money worship and hedonism.” It does invoke Communist slogans such as “core socialist values,” but in contrast to the previous such document from 2001 — which made only passing reference to Chinese traditions — it calls the past a “rich source of morality.” The plan orders party officials to promote “ancient and worthy sages,” as well as to “deeply expound” traditional concepts such as “ren’ai” (benevolence), “zhengyi” (righteousness) and “jianyi zhengwei” (standing up bravely for the truth).

“This effort is not an attempt to replace Communism with Confucianism. Yet it is fair to say that for the first time since China’s imperial order collapsed in 1911, a central government is embracing the ideas that made up the political-religious order that ran China for much of the past 2,500 years. Why? Not only to address China’s moral vacuum, but also as a populist measure. The country is entering a more uncertain era, of slower growth and rising inequality, and Beijing is draping itself in the mantle of tradition to broaden its appeal. In doing so, the government seems to be assuming that traditional Chinese values and beliefs are easier to control than foreign religions, and that supporting them will outweigh the costs of suppressing Islam and Christianity. But I have my doubts."

Image Sources: Evangelical gathering, Open Door com. Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2021