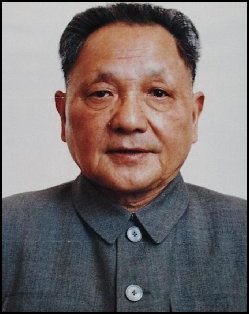

DENG XIAOPING

Deng Xiaoping was the leader of China from 1978 (two years after Mao's death) until his death in February, 1997. The last of the great revolutionary leaders of China and a Time Man of the Year twice (in 1979 and 1985), he was both a reformer and despot. His life was touched by all the major events of modern Chinese history and his 18 years as "paramount leader" dramatically changed the course of Chinese history.

Deng Xiaoping was the leader of China from 1978 (two years after Mao's death) until his death in February, 1997. The last of the great revolutionary leaders of China and a Time Man of the Year twice (in 1979 and 1985), he was both a reformer and despot. His life was touched by all the major events of modern Chinese history and his 18 years as "paramount leader" dramatically changed the course of Chinese history.

" Deng was purged three times in his nearly 50 years in the party's upper ranks. He never held the posts of head of state or head of government, but nevertheless succeeded Mao Zedong as China's paramount leader from 1978 to the early 1990s.

"Deng considered the ultimate purpose of his life to be reform. For that, he struggled — and suffered — with courage and dedication," wrote Henry Kissinger. Under Deng, China modernized more in 20 years than it did in the previous 200 years and rose from an economic backwater into one of the world's largest economies. GNP increased 500 percent between 1978 and 1995; per capita annual income rose from a few hundred dollars to $1,800; savings increased 14,000 percent; and export went from $10 billion a year to $153 billion.” According to a 1998 survey, Deng (pronounced "dung") was named the number one hero in China. Mao ranked fifth.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; AFTER MAO: THE RISE OF DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING: POLICIES, SPEECHES, SLOGANS AND POLITICS factsanddetails.com; POLITICAL REFORM AND SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; FOREIGN POLICY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S EARLY ECONOMIC REFORMS factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING STEPS UP HIS ECONOMIC REFORMS: SEZS AND HIS SOUTHERN TOUR factsanddetails.com; WEI JINGSHENG, FANG LIZHI, HARRY WU: DISSIDENTS, POLITICAL ACTIVISTS AND PRISONERS IN CHINA FROM THE 1990s factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE AND EARLY OPPOSITION MOVEMENTS factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE DEMONSTRATIONS, 1989 factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE: VICTIMS, SOLDIERS AND EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS factsanddetails.com; DECISIONS BEHIND THE TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE factsanddetails.com; AFTERMATH, IMPACT AND HISTORICAL RESEARCH OF TIANANMEN SQUARE factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF TIANANMEN SQUARE: VICTIMS COPE, OTHERS FORGET factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE POLITICAL ACTIVISTS AND PRISONERS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources on Deng Xiaoping: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; CNN Profile cnn.com ; New York Times Obituary; China Daily Profile chinadaily.com. ; Wikipedia article on Economic Reforms in China Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Special Economic Zones Wikipedia ; History Websites: 1) Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia 4) China Knowledge; 5) Gutenberg.org e-book gutenberg.org/files ; Links in this Website: Main China Page factsanddetails.com/china (Click History)

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Deng Xiaoping "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com;

“Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life” by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine Amazon.com;

"Deng Xiaoping: My Father" by Deng Maomao (1995, Basic Books) Amazon.com;

“Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991"

by Xiaoming Zhang Amazon.com;

“The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994"

by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com;

"Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping" by Richard Baum (1996, Princeton University Press) Amazon.com;

"Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com;

"Deng Xiaoping: Chronicle of an Empire" by Ruan Ming (1994, Westview Press) Amazon.com;

"Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China" by Richard Evans 1993 Amazon.com;

"Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman" edited by David Shambaugh (1995, Clarendon Paperbacks) Amazon.com;

"The New Emperors: Mao and Deng — a Dual Biography" by Harrison E. Salisbury (1992, HarperCollins) Amazon.com

Ezra Vogel's Book on Deng Xiaoping

Deng in the Soviet Union in 1929

John Pomfret of the Washington Post called Ezra F. Vogel’s in "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" “a masterful new history of China's reform era” and “the clearest account so far of the revolution that turned China from a totalitarian backwater...into the power it has become today.” Pieced together from interviews and memoirs it is a massive book whose text runs to 714 pages. [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

Vogel, a Harvard professor, spent more than a decade writing the book. He argues that Deng deserves a central place in the pantheon of 20th-century leaders. For he not only launched China's market-oriented economic reforms but also accomplished something that had eluded Chinese leaders for almost two centuries: the transformation of the world's oldest civilization into a modern nation.

Pomfret wrote in the Washington Post, “The book is not without its weaknesses. Vogel is so effusive in his praise of Deng that the book sometimes reads as if it came straight from party headquarters. Vogel also portrays dissidents who have fought China's authoritarian system as troublemakers blocking Deng's mission of modernization. He seems highly sympathetic to Deng's — and the party's — argument that if China allowed more freedom, it would devolve into chaos, as if stability under the party's rule or pandemonium were the only choices.

In his review of the book, Perry Anderson wrote in the London Review of Books: “ " Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" is an exercise in unabashed adulation, sprinkled with a few pro forma qualifications for domestic effect. “The closest I ever came to Deng was a few feet away at a reception “” captures the general tone. Fortunately, Deng’s family and friends were able to make good the missing encounter, with many a gracious interview illuminating the patriarch’s life. [Source: Perry Anderson, London Review of Books, February 9, 2012]

Anything in Deng’s career that might seriously mar the general encomium is sponged away. Of the Anti-Rightist campaign of 1957-58 of which he was the executor, dispatching half a million suspects to ostracism, exile or death, we learn that he was “disturbed that some intellectuals had arrogantly and unfairly criticised officials who were trying to cope with their complex and difficult assignments”. Suppression of the first halting demands for political democracy in 1978" “As in imperial days, order was maintained by a general decree and by publicising severe punishment of a prominent case to deter others.” Incarceration of its young spokesman for 15 years” Arrests were “infinitesimal” compared with days gone by, and “no deaths were recorded.”

Tibet” Despite enlightened efforts to “reduce the risk of separatism”, Lhasa has had to witness a “tragic cycle” of “riots” and “crackdowns”; still, “Tibetans and Han Chinese both recognise — an improvement in the standard of living” and Tibetans are slowly “absorbing many aspects of Chinese culture and becoming integrated into the outside economy”. Nothing shows Vogel’s sense of decorum, and priorities, better than his decision to omit so much as a mention of the Stalinist show trial of Lin Biao’s hapless subordinates, brigaded on trumped up charges with the Gang of Four, with whom they had nothing in common, a decade after the death of their commander, and on Deng’s orders condemned to long terms in jail in the full glare of publicity — a top political episode of 1980-81.

Book: "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011)

Deng Xiaoping, the Cute Little Revolutionary

Deng Xiaoping was only 4 feet, 11 inches tall. He was so short that when he sat in a large chair his feet hung in the air above the floor. A pragmatic figure with little of the charm or charisma of Mao, Deng liked to gesture when he talked and spoke with a guttural Sichuanese accent. Occasionally, he displayed bursts of impatience and anger. Otherwise he was a man of few words, who disliked chit chat and liked to get right to the point.

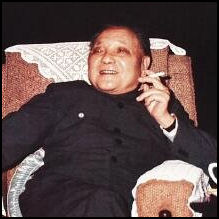

Deng was a "crafty, obsessive" bridge player and, like Mao, he occasionally went swimming surrounded by a dozen bodyguards. Deng chain smoked Chinese-made Panda-brand cigarettes (unlike Mao who preferred the British brand 555), which gave him a gravely voice and brown-stained fingers. He reportedly smoked right up until his death at 92 and was often photographed with a cigarette in his hand.

Deng was also a notorious spitter. He kept a spittoon near his chair in the Great Hall of the People and was not shy about hacking and spitting in public or spitting while making an important point when he met with foreign dignitaries or world leaders. One of Deng Xiaoping's favorite foods was "Double Taste Fiery Pot,"' a dish prepared in a special double sided pot with a Yangtze River fish that is salty on one side and spicy on the other.

Wei Jingsheng, a dissident he served long jail terms for challenging Deng, wrote that Deng had a "talent for persuasion and an ability to reinvent himself to suit the peculiarities of those around him...He was excellent debater, he was an appalling theorist...Despite Deng's ruthless behavior, he had the capacity for introspection, even regret."

What Other People Said About Deng Xiaoping

in 1934

Mao reportedly once described Deng as gentle but firm like a needle in cotton. "His mind is round and his actions square," Mao told Khrushchev, "Don't underestimate this little fellow...He's highly intelligent and has a great future ahead of him."

In her biography of her father "Ten Thousand People, One Heart", Deng's daughter Deng Maomao wrote: "We love him, but we're also in awe of him...he doesn't like to talk. So I don't often get to really chat with him about anything...Even we, his family know little of his past."

"Unlike Mao, who exaggerated difference," wrote historian Orville Schell in Newsweek, "Deng was skilled at coalition and consensus building. And while Mao tended to revel in titles, the unflamboyant Deng did not, refusing to become chairman of the party, prime minister of the State Council or president...While Deng could be opportunistic, he was remarkably constant in his beliefs and predictable in his actions, especially when it came to economics. He rarely tormented himself over difficult decisions. His self confidence allowed Deng to take enormous gambles."

Diplomat Richard Holbrooke wrote in Time: "His grandfatherly appearance made him seem cute. But Deng Xiaoping was not cute; he was far tougher than Americans could possibly imagine. He surely viewed life as a constant struggle, because that is what his whole life had been." Deng "was an old man in a hurry; he saw visitors, but only if they could advance the central goal of his life — to make China great again. In the hours of talks I attended with him, he expressed little personal interest in his foreign visitors except for their technology, which he wanted immediately...His small eyes focused on you with intensity. Then he would look away, perhaps at some distant vision of the China he wanted to build...he exuded enormous energy and sharp focus."

Deng Xiaoping's Early Life

Deng Xiaoping was born as Deng Xiansheng ("First Saint") in Baifang village in Guangan, a poverty-stricken area of Sichuan on August 22, 1904. He was the eldest son of a county sheriff and affluent landowner. One of his ancestors was a famous Chinese scholar. People from his village remember him as a small boy who liked to turn somersaults. Deng left the Sichuan countryside for France when he was 16.

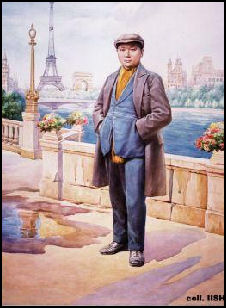

In 1920, at the age of 16, Deng left his rural village for Shanghai, where he won a work-study scholarship for a program in Paris. "We felt China was weak, and we wanted to make it strong," he later said. "We thought the way to do it was through modernization. So we went West to learn." He never went to school after that.

Deng in France

In France, Deng learned how to play bridge; became such a devoted soccer fan he once sold his overcoat to buy a ticket to a game; and developed a taste for croissants (in a 1974 stopover in Paris after a trip to New York he ordered 100 croissants). He was also introduced to Communism and changed his name to Deng Xiaoping ("Little Peace").

Deng spent five years in France at a time when Europe was stuck in a post-World-War-I recession. He reportedly developed his antipathy towards capitalism through his experiences working in France as a part-time arm factory worker, a fitter at a Renault factory, a train conductor and a shoe assembler. The more he worked at these places the more he became involved in Communist activities.

Deng moved from town to town as he changed jobs. In 1922 he made shoes for eight months at a rubber plant in the town of Montargis, about 100 kilometers south of Paris. He lived behind one of the plants workshops and worked around glue that emitted toxic benzene vapors. Before he left his boss wrote: “Refuses to work. Don’t rehire.” Montargis is now trying to attract Chinese tourists with Deng tours.

Communism was popular among laborers in France after World War I. In 1922, Deng joined a Communist Youth League set up by overseas Chinese. He helped distribute the party newsletter, which earned him a mock degree of "Doctor of Mimeography." Before returning to China in 1926, he studied Marxist-Leninist thought in Moscow.

Deng Xiaoping's Family

Deng was married three times. Little is known of his first wife. She died in childbirth in 1930. His second wife divorced him in when he was in political trouble in 1933 and married a man, whose accusations forced Deng to endure brutal self-criticism sessions within the Communist Party. Deng met and married his third wife, Zhuo Lin, in Yenan shortly after the end of the Long March. They were married in 1939 and had five children. Zhuo Lin died in 2009 at the age of 93.

After her death, according to Associated Press, the central committee said Zhuo, who was born in southwestern Yunnan province in 1916 and joined the party in 1938, was an excellent party member and a "time-honored loyal communist fighter," Xinhua said. Zhuo was not politically active and most of her public appearances were limited to ceremonial occasions. In 1997, months after Deng died, Zhuo and daughter Deng Nan attended festivities in Hong Kong marking the return of the British colony to Chinese rule, as a tribute to Deng's role in winning back the territory. [Source: Associated Press, July 29, 2009]

Deng was regarded as a committed family man. He fathered two sons and three daughters. One his greatest joys in the last years of his life was spending time with his grandchildren. Like Mao, Deng Xiaoping also had his share of extramarital affairs. According to Mao's doctor Dr. Li Zhisui he impregnated a young nurse who had been sent from Shanghai to "serve Mao."

Deng’s son Deng Pufang was given a special United Nations human rights prize for his work helping the handicapped (See Cultural Revoultion). In 2008, he was selected as vice chairman of the People’s Political Consultive Conference (CPPCC).

Deng Xiaoping's Revolutionary Past

Deng in 1941

Upon returning to China in 1926. Deng joined the fledgling Chinese Communist party. His early assignments included helping a Soviet-supported warlord and raising a peasant army in remote areas of Guanxi province, where he met up with Mao Zedong.

According to one report in the 1930s Deng ordered the execution of a battalion commandeer who shot a dying man who was in great pain to put him out of misery. Deng criticized the commander for making a decision based on emotion.

Deng Xiaoping was inspired by Mao's doctrine of peasant revolution which made him unpopular with the pro-Moscow factions within the party. He was briefly jailed. Between 1931 and 1935, Deng worked with Mao in the Jiangxi province setting up a base for the Red Army. When Mao was kicked out of the Communist Party for advocating guerrilla fighting tactic, Deng was ousted along with him.

Deng accompanied Mao on the Long March in 1936. When his daughter later asked what he did, he replied, "Just followed." When it was over he was exhausted and ill with typhoid. During the Long March, Deng became close with Mao, who gave him a high position in the "government" that controlled large parts of northern China. He had successes with programs like the "great production movement" which aimed to boost grain harvest by rewarding hard work. A U.S. military contact who met Deng during this period said he was "short, chunky and physically tough, with a mind as keen as mustard."

Deng in Mao's Communist Government

In a review of "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra Vogel, John Pomfret of the Washington Post wrote Vogel argues that “Deng took an early fall for Mao, convincing the would-be chairman of his loyalty during the initial days of China's revolution. Mao soon began relying on Deng as his henchman. Deng spearheaded Mao's attack on China's learned class in the 1957 "Anti-Rightist Campaign," organizing the purging, criticizing and jailing of about 550,000 of China's best and brightest. Mao also relied on Deng to fix the messes that he routinely made of China's economy — such as the famines (30 million dead) of the disastrous Great Leap Forward and, later, of the Cultural Revolution. Mao might have been a monster, but he was a monster with a back pocket, and Deng was always there.” [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

In a review of "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra Vogel, John Pomfret of the Washington Post wrote Vogel argues that “Deng took an early fall for Mao, convincing the would-be chairman of his loyalty during the initial days of China's revolution. Mao soon began relying on Deng as his henchman. Deng spearheaded Mao's attack on China's learned class in the 1957 "Anti-Rightist Campaign," organizing the purging, criticizing and jailing of about 550,000 of China's best and brightest. Mao also relied on Deng to fix the messes that he routinely made of China's economy — such as the famines (30 million dead) of the disastrous Great Leap Forward and, later, of the Cultural Revolution. Mao might have been a monster, but he was a monster with a back pocket, and Deng was always there.” [Source: John Pomfret, Washington Post, September 9, 2011]

“Mao also had Deng manage key elements of China's split with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s. Deng locked horns with Mikhail Suslov, the Soviets' chief ideologue, and with party leader Nikita Khrushchev, too. Mao, Vogel writes, was petrified that his followers would do to him what Khrushchev did to Stalin — condemn him. After Deng's vitriolic attack against the Soviets, Mao was persuaded that his legacy was safe with Deng.”

Deng rose from 28th in the Communist ranks in 1945 to one of Mao's 12 Deputy Premiers in the mid-1950s. Deng was in Moscow in 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev stunned Communist leaders at the Party Congress by denouncing Stalin's personality cult. Deng recommended that the Chinese Communist also abandon Mao-worshiping, a move that later came back to haunt him in the Cultural Revolution.

In the late 1950s, Deng oversaw the Anti-Rightist movement which claimed over 700,000 victims. He knew of and ordered the execution of thousands of landlords. Deng also reportedly directed the occupation of Tibet in 1950s and opposed the "Hundred Flowers Bloom" program of liberalization on the grounds that changes should be made from within the party not by the people. Deng played a key roles in the crackdown of the movement.

Deng’s pragmatic approach repeatedly drew the ire of party radicals. Mao and Deng had a falling out over the Great Leap Forward. Deng refused to carry out many of Mao's ridiculous agricultural reforms, a move that saved thousands of lives but embarrassed Mao. In 1962, Mao jumped on Deng for not sitting next to him at a party meeting and screamed, "You have put the screws on me for the last time!...Now, for once, I am going out put a screw in you."

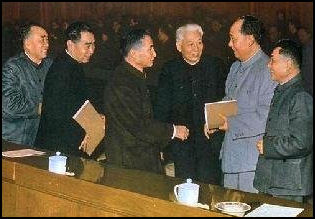

with Mao at an international workers meeting

Deng During the Cultural Revolution

In 1966, during the Cultural Revolution, Deng was labeled as the "No. 2 Capitalist Roader" and swas tripped of his position as Party General Secretary. During a humiliating self criticism session Deng was accused of being a "fascist," a "traitor" and a practitioner of cat-ism (a reference to his white cat, black cat remark). During the sessions, Red Guards shouted, "Cook the dog's head in boiling oil!" When the noise became too much, Deng used to remove his hearing aid.

In 1968, Deng's son was paralyzed after jumping (or being pushed) from a window to escape members of the Red Guard. Deng younger brother was driven to suicide by Red Guard attacks. Deng himself was put under house in Beijing for two years and then sent to Jiangxi province where worked in a tractor-repair factory and was confined to an infantry school, a fate that could have much worse. Later he said, "Chairman Mao protected me." Mao uncharacteristically apologized to Deng for the purge.

One of Deng’s cousins told the Los Angeles Times, ‘since I was his relative, students would come from Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and make us kneel on stools wearing a dunce cap with a sign around our neck that said “corrupt, bankrupt landlord.' A little later he [Deng] wrote us a letter and gave us money, apologizing because we’d been affected by him.”

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: In 1979, three years after the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping visited the United States. At a state banquet, he was seated near the actress Shirley MacLaine, who told Deng how impressed she had been on a trip to China some years earlier. She recalled her conversation with a scientist who said that he was grateful to Mao Zedong for removing him from his campus and sending him, as Mao did millions of other intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution, to toil on a farm. Deng replied, “He was lying.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, May 6, 2016]

Deng in his revolutionary days

Deng's Resurrection

In 1973, Deng was called back to Beijing to help extract China from the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. The between-the-lines announcement of his return from political oblivion was his inclusion on the guest list for state dinner for Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia mentioned in a party newspaper and his entrance on the arm of Mao's favorite niece. Not only was Deng rehabilitated, he was named vice prime minister and vice chairman of the powerful Central Military Commission.

Deng was purged from the Communist Party three times: in 1933 as a mid-level party official; in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution; and in 1976 during a dispute with the Gang of Four, who called Deng a "counterrevolutionary." "I have been deposed before," Deng said after being ousted by the Gang of Four. "Do you think I am afraid of being deposed again?" The exile in 1976 lasted only a few months.

Deng survived by laying low after he had been purged and waiting for his allies to rehabilitate him. During much of his political career his great patron was Mao himself. Zhou also helped rehabilitate Deng. On his deathbed in 1976 Zhou reportedly told Deng: "The work you have accomplished in the past year proves you are much stronger than me."

Deng was restored to his official posts in July 1977. His “reform and opening” policy was approved at the same party meeting in December 1978 in in which his rival Hua Guofeng was ousted.

Deng's Last Years

Deng formally retired from politics in 1987, resigning all his leadership positions in the Communist party and the military. He kept only one title: the Honorary Chairman of the China Bridge Association. Even so, there was no question that he was the paramount leader and major decisions by the politburo needed his approval.

Presidential advisor Brent Scowcroft met with Deng when he was 87. At the end of the meeting the Chinese leader told him to send his warmest regards to Jimmy Carter. The only problem was that George Bush was the president, and Ronald Reagan served eight years before him. Jimmy Carter hadn't been president for more than a decade.

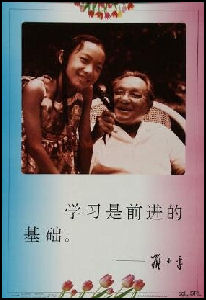

Deng and his granddaughter

Deng lived in a block-long bungalow called Miliangku (literally "rice-grain storehouse") in Beijing with more than a dozen members of his extended family, and reportedly spent most of his time playing bridge and amusing his great grandchildren. Up until 1995, twice a day, he walked the 165 yard distance around the courtyard of his home 20 times.

Deng was 88 when he showed up in Shenzhen in 1992 for the Southern Tour. After that he wasn't seen in public for two years. When Deng last appeared in public, in February 1994 for a Lunar New Year celebration, he looked dazed and disoriented.

At the end of his life, Deng suffered from Parkinson's Disease, perhaps diabetes and kidney dysfunction, and an unspecified cancer. He was also almost blind and hard of hearing. His speach was reportedly so slurred that two of his three daughters were the only people who could understand what he said. Always nearby was a VIP Health Unit with a physician and a psychiatrist.

Deng's daughter Xiao Rong told the New York Times in 1995 that her father "can not walk. He needs two people to support him." He refuses to sit in a wheel chair because she said, "He feels that after he sits in a wheelchair, he won't be able to get up again." When documents were shown to Deng on papers with oversized characters printed on them, he either nodded, mumbled or shook his head and his daughter tried to decipher what he meant.

In January, 1995 Deng reportedly had slipped into a "vegetative state," and was kept alive by machines and a team of doctors at Army No. 30 Hospital in Beijing. One source said the Chinese leader might remain in that condition for weeks or months." Xia Rong told the New York Times that his "health declines day by day."

Deng Xiaoping's Death

Deng Xiaoping died in February, 1997 at the age of 92, of Parkinson's disease, respiratory illness and old age. Deng had earlier described his death as the day when he must "go meet Marx." Deng told his family he hoped before he died to witness the handover of Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule, and to attend an Olympic Games in Beijing. But he missed both. Deng, like Mao, was not featured in the opening or closing ceremonies. [Source: Ross Terrill, The China Beat, February 26, 2010]

Ten thousand people, none of them foreigners, attended Deng's low key memorial service. His eyes were donated to medicine as was his wish; his body was cremated; his ashes were cast into the sea; and no monuments were raised in his honor. His body was incinerated in a special crematorium reserved for top leaders in a 15-minute ceremony attended by close relatives

Flags flew at half mast and there was a six-day ban on nightlife, but otherwise there were few signs that paramount leader had died. People went about their business, the Shanghai stock market remained steady, and there was no great outpouring of grief like there was after Mao died. When asked about Deng's death, one taxi driver told Time magazine, "Everybody is too busy making money to feel sad.”

Ross Terrill wrote, “Foreign China specialists, including me, overestimated the crisis China would face with Deng’s death In fact, the event was not at all like Mao’s death. China’s political system had matured in the two decades between 1976 and Deng’s death in 1997. Mao-as-an-institution had given way to a quite different kind of CCP leadership. There was not in February 1997 the stunned uncertainty that had existed in September 1976.” [Source:Ross Terrill, The China Beat, February 26, 2010]

Deng's Legacy

Xiao Rong

Some historians argue that the political situation in China after Deng's death was not unlike that of 19th century China at end of the Qing Dynasty, when efforts were made to modernize China while keeping the dynasty intact. On Deng Xiaoping, Howard W. French wrote in The Nation that interpretations of history often amount “to a way of averting one's eyes from something that may seem too hard to comprehend...This is the ultimate sense of the famous posthumous verdict by Deng Xiaoping, who judged that Mao had been 70 percent “correct” and 30 percent wrong. Yes, Mao's errors, like the 30 million or more deaths from starvation caused by the crash industrialization of the Great Leap Forward, were doozies, but by and large he kept the country on the right path, avers Deng Xiaoping. Deng's past has also benefited from studious airbrushing to avoid mussing up the standard portrait of him as a kindly, strong and nearly infallible second father to the nation. His enthusiastic role in violently suppressing “rightists” in the late 1950s has been placed out of bounds by the gatekeepers who determine which subjects can be researched and which cannot. [Source: Howard W. French, The Nation, August 4, 2008]

Deng is given the most credit for his economic reforms, some of which were embraced by his own family. Deng Xianyan, a Deng cousin who sells Deng family liquor, told the Los Angeles Times, “He unleashed the creativity of a billion Chinese people.” The liquor he sells has black and white cats on the label. One bottle is shaped like an upward thumb. Consumers are told to drink it in three gulps not one to represent the “three ups and downs” of Deng’s career.

Not everyone thinks the Deng reforms were so good. One retired factory worker told the Los Angeles Times, ‘sure, a lot of people have gotten rich from Deng’s reforms. But even more people have lost their jobs. You need wooden doors, metal gates and two locks against the thieves. You’re constantly worrying someone might kidnap your grandson. There’s so much stress and pressure. How can you call this progress?”

The 10th anniversary of Deng’s death in 2007 passed without much fanfare. The state-run media barely mentioned the occasion and no major special events were announced. However, thousands visited his house in his hometown to offer their tributes. Wristwatches and tea sets with his face sold briskly. Politicians praised his economic reforms. The treatment was ironic in that Deng had great contempt for the personality cult that was built up around Mao.

Deng Xiaoping: The Made-for-TV “Thriller”

In the summer of 2014, “Deng Xiaoping at History's Crossroad” was aired on Chinese television to celebrate the life former leader whose reforms transformed China into economic giant on 110th anniversary of Deng’s birth. Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “It is not exactly House of Cards, despite one state newspaper's breathless claim that the first episode "resembles a typical Hollywood political thriller". But China's latest television drama depicts a turbulent time” when Deng emerged as China's paramount leader in the years after Mao Zedong's death” and “follows his return from the political wilderness and pursuit of the reform that transformed his country into an economic giant. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, August 15, 2014 ^^^]

“Deng Xiaoping at History's Crossroad spans 48 episodes, took three years to write and cost 120 million yuan (about $18 million), a lavish sum by the state broadcaster's standards. Party bodies oversaw the production. Lest anyone miss the possible contemporary parallel with the story of a bold leader pursuing economic changes while maintaining the party's political grip, state media have carried a commentary stressing president Xi Jinping's veneration of Deng. This is the anniversary year and of course they will give Deng Xiaoping status as the architect of reforms; it's on the agenda anyway. Then, there is whatever Xi can do to put his ideas into this programme and highlight some aspects [of Deng] or obscure others to serve his agenda," said Feng Chongyi, associate professor in China Studies at the University of Technology, Sydney. ^^^

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see The Guardian

Deng's Grandson Promoted in China

In June 2014, the grandson of Deng Xiaoping was given his first low-level leadership post in Guanxi, area where his grandfather made history. Deng Zhuodi "has taken up the post of Pingguo county's Xinan township party committee secretary" in Baise city, in the southern region of Guangxi, the official China National Radio said in an online report. Deng, who is believed to be around 30, is also deputy chief of Pingguo county, a post he took up in 2013, the report said. Baise is of particular significance because Deng Xiaoping launched an uprising there in 1929 in one of the earliest battles in China's brutal civil war. [Source: AFP, June 24, 2014]

AFP reported: “Spending time in the countryside is sometimes seen as a way for aspiring officials to burnish their credentials. Many children of the founding leaders of Communist China have risen up the ranks of officialdom, some from humble rural positions but the third generation have often sought lucrative careers in business. Mao's own grandson Mao Xinyu holds the rank of major-general in the Chinese military and is a delegate to the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, a debating chamber that is part of the Communist-controlled governmental structure, but according to his biography has never been put in charge of a party organisation.”

Image Sources: Wikicommons, Wikipedia and Nolls China websites http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2016