TIANANMEN SQUARE DEMONSTRATIONS, 1989

In 1989, broad political and economic discontent combined with inspiration from dramatic change in the former Soviet Union and other parts of eastern Europe sparked student-led protests in Beijing that were crushed, but only after setting off heated debate at the top of the party about whether it should introduce serious political reform.

In 1989, broad political and economic discontent combined with inspiration from dramatic change in the former Soviet Union and other parts of eastern Europe sparked student-led protests in Beijing that were crushed, but only after setting off heated debate at the top of the party about whether it should introduce serious political reform.

Some Chinese call it “the June 4th Incident.” At 2:00am on June 4th 1989, People's Liberation Army tanks and 300,000 soldiers moved into Tiananmen Square in Beijing to crush a large pro-democracy demonstration that had been going on for seven weeks. Hundreds of students and supporters were killed. The tanks rolled over people that got in their way and soldiers opened fire on groups of protesters. There is little mention of it now in China. When it is mentioned it is called a ‘sensitive topic.” The protests were seen by the Communist Party elite as a direct threat to their rule. Preserving economic development was given as a reason to justify suppressing the Tiananmen protests and maintaining One-party rule.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In 1989, China’s reforms seemed to have turned sour. The economy was in a downturn. Inflation reduced the buying power of workers’ and intellectuals’ fixed state salaries. Corruption from the lowest to the highest levels of the Communist Party, and the spectacle of “princelings” (children of high-ranking Party leaders) using their connections to amass business fortunes sickened idealistic intellectuals and ordinary people. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang (b. 1915) died on April 15, 1989. Hu had a reputation for honesty and integrity. Also, his somewhat sympathetic attitude toward intellectuals and student protesters had lost him the Party Secretary position after the student demonstrations of 1986. Thus, the occasion of public mourning for Hu Yaobang quickly turned into an occasion for students and citizens of Beijing to protest against corruption and in favor of democracy. The fact that the world press was in Beijing to cover the historic visit of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev provided further incentive for the protesters.

“As protesters took over Tiananmen Square in the heart of the city during the latter part of April, the government attempted to bring the situation under control and published an editorial in the Party newspaper, People’s Daily, which labeled the protesters as counter-revolutionary conspirators. The editorial inflamed the students’ passions and simply brought more people into the demonstrators’ ranks. The government was unable to respond clearly in any way to the students at this time: divisions had appeared within the Party leadership, with Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang (1919-2005) arguing for a more conciliatory approach and dialogue with the students, while Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997) and other Party leaders favored taking a hard line.”

Good Websites and Sources on the Tiananmen Square Protests: ; Tiananmen Square Documents gwu.edu/ ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; BBC Eyewitness Account news.bbc.co.uk Film: "The Gate of Heavenly Peace" has been praised for its balanced treatment of the Tiananmen Square Incident. Gate of Heavenly Peace tsquare.tv

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING: POLICIES, SPEECHES, SLOGANS AND POLITICS factsanddetails.com; POLITICAL REFORM AND SOCIALIST DEMOCRACY UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; WEI JINGSHENG, FANG LIZHI, HARRY WU: DISSIDENTS, POLITICAL ACTIVISTS AND PRISONERS IN CHINA FROM THE 1990s factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE AND EARLY OPPOSITION MOVEMENTS factsanddetails.com; DECISIONS BEHIND THE TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE factsanddetails.com; TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE: VICTIMS, SOLDIERS AND VIOLENCE factsanddetails.com ; TIANANMEN SQUARE MASSACRE: EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS AND SURVIVOR STORIES factsanddetails.com ; TIANANMEN SQUARE AFTERMATH, IMPACT AND LEGACY factsanddetails.com TIANANMEN SQUARE POLITICAL ACTIVISTS AND PRISONERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement” by Timothy Brook, regarded as the most complete book on Tiananmen Square Amazon.com; “The Tiananmen Papers” by Zhao Ziyang Amazon.com; “Inconvenient Memories: A Personal Account of the Tiananmen Square Incident and the China Before and After” by Anna Wang, Lisa Cordileone, et al. Amazon.com; “Tiananmen Square : The Making of a Protest” by Vijay Gokhale Amazon.com; “Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China (Palgrave Studies in Oral History) by Rowena Xiaoqing He Amazon.com; “The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited Illustrated Edition” by Louisa Lim Amazon.com; “Tiananmen 1989: Our Shattered Hopes” by Lun Zhang, Adrien Gombeaud Amazon.com; Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com;

Background Behind Tiananmen Square Protests

Zhao Ziyang (1919- 2005) became the general secretary of the Communist Party of China in 1987 and was the second most powerful man in China after Deng Xiaoping. He was in charge of the political reforms in China from 1986 and in the view of many the mastermind behind Deng’s economic reforms in the 1970s and 80s.

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: After Zhao became the party General Secretary, the economic and political reforms he had championed came under increasing attack. His proposal in May 1988 to accelerate price reform led to widespread popular complaints about rampant inflation and gave opponents of rapid reform the opening to call for greater centralization of economic controls and stricter prohibitions against Western influence. This precipitated a political debate, which grew more heated through the winter of 1988-89. [Source:“Countries of the World and Their Leaders” Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

“The death of Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989, coupled with growing economic hardship caused by high inflation, provided the backdrop for a large-scale protest movement by students, intellectuals, and other parts of a disaffected urban population. University students and other citizens camped out in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to mourn Hu's death and to protest against those who would slow reform. Their protests, which grew despite government efforts to contain them, called for an end to official corruption and for defense of freedoms guaranteed by the Chinese constitution. Protests also spread to many other cities, including Shanghai, Chengdu, and Guangzhou.

Beginning of Tiananmen Square Demonstrations

The demonstration were triggered in March by a claim in the official Communist party paper People’s Daily that a student group was plotting a coup d etat. Students from three dozen universities marched on the square,

The pro-democracy demonstrations began in earnest as a display of public morning for Hu Yaobong — a reformist Communist leader who was once chosen as Deng's successor but later was purged for advocating political reform — who died of cancer on April 15, 1989. Thousands left wreaths at Tiananmen Square to honor him. Although Hu was not a leader in a reformist movement he was a sympathizer to reformist causes and his death prompted students, teachers, intellectuals, workers, reformists and ordinary Chinese to gather at Tiananmen Square.

A week after Hu's death 150,000 students had assembled in Tiananmen Square. By the end of May there were nearly a million. Students from all over China, some of whom had been assisted by railway workers who let them ride free on the trains, came to Beijing for the protests. They were supported by millions of ordinary Chinese citizens, and at one point there was even some discussion that soldiers might defect to the side of demonstrators.

A week after Hu's death 150,000 students had assembled in Tiananmen Square. By the end of May there were nearly a million. Students from all over China, some of whom had been assisted by railway workers who let them ride free on the trains, came to Beijing for the protests. They were supported by millions of ordinary Chinese citizens, and at one point there was even some discussion that soldiers might defect to the side of demonstrators.

Students from Peking University organized "democracy salons" and street marches. Banners were unfurled that read "Give me Liberty or Give me Death." A broadcast tent and daily newspaper were launched and a "conference hall” was set up at the Tiananmen Square Kentucky Fried Chicken. Students wrote a petition to party leaders with their own blood because blood. The atmosphere at first was like a big party or Woodstock. The students demands were relatively mild. They avoided confrontation and turned over to police people who had flung ink on the large portrait of Mao in Tiananmen Square.

Looking back on the 1989 protests,Wang Chaohua, a leader of the Tiananmen protests, wrote in Hong Kong’s Ming Pao newspaper in 2009: “In the first ten days or so, the great majority of protesters were students. When Hu Yaobang’s funeral was held on April 22 and the casket was carried from the funeral site, the Great Hall of People by Tiananmen Square, to its final resting place in west suburban Beijing, there were not many people spontaneously lining up the big thoroughfare to pay their final tribute to Hu — at least, far fewer than had turned more than a decade earlier, when there was a massive showing at the funeral of former Premier Zhou Enlai in January 1976. Those mourning crowds sent political shock waves through the capital.[Source: The China Beat, May 8, 2009, Wang Chaohua is an independent scholar who received her doctorate from UCLA in 2008. She has written political commentaries for periodicals such as the New Left Review, and is the editor of One China, Many Paths.

What the Tiananmen Square Demonstrators Were Protesting

It was somewhat unclear exactly what the purpose of the demonstrations were. Han Dongfang, a labor organizer at Tiananmen Square, told the Los Angles Times, "Tiananmen was a historical misunderstanding. At that time nobody knew what they wanted, including the students and the workers—including myself. It was an unripe fruit."

At first many of the students were protesting the conditions in Beijing University, where students often didn't have enough to eat and squeezed eight people in dormitory rooms meant for two. Later the protesters lashed out against corruption, nepotism, hardships brought about by inflation, lack of press freedom, and the slow pace of reform. They demanded freedom of speech and wanted recognition that they were patriots not troublemakers. Many were angry with corruption by so-called 'princelings', children of top Chinese Communist Party leaders. They also called for democracy but had no clear objectives, demands or proposals. Student leader Chai Ling said, "We wanted to overcome politics...We loved life so much that were willing to give it up for others. It was totally sincere.”

One World Crew in Beijing in 1988

Liao Yiwu wrote in the NY Review of Books: “Before the Tiananmen massacre, my father told me: “Son, be good and stay at home, never provoke the Communist Party.” I was barely thirty and didn’t heed my father’s warning. I admired the American Beat Generation, their spirit and their actions. I was “on the road.” All through China, in dozens of cities, dozens of millions of protesters marched on the roads. Most of them were younger than I was, they would never heed their parents’ warnings. Especially the “Pride of Heaven,” as they were called, the university students in the capital, who had occupied Tiananmen square for weeks, under the eyes of the world, heady with drugs—freedom and democracy![Source: Liao Yiwu, NY Review of Books, June 3, 2014, Translated by Martin Winter ***]

Most of the participants were students from northern China, who have traditionally been regarded as more politically inclined than their counterparts in the south. Many were from the urban elite, some of whom looked down on peasants as bumpkins. But not only students participated. The demonstration attracted people from a wide range of groups: trade unionists, newspaper editors, government intermediaries, famous intellectuals, political liaison groups and ordinary Chinese.

Life in China at the Time of the Tiananmen Square Protests

Describing his experiences at Tiananmen Square the writer Yu Hua wrote in the New York Times,”Protests were spreading across the country, and in Beijing, where I was studying, the police suddenly disappeared from the streets. You could take the subway or a bus without paying, and everyone was smiling at one another. Hard-nosed street vendors handed out free refreshments to protesters. Retirees donated their meager savings to the hunger strikers in the square. As a show of support for the students, pickpockets called a moratorium.” [Source: New York Times, May 30 2009, Yu Hua is the author of Brothers. This essay was translated by Allan Barr from the Chinese.

If you live in a Chinese city, you’re always aware that you are surrounded by a lot of people. But it was only with the mass protests in Tiananmen Square that it really came home to me — China is the world’s most populous nation. Students who had poured into Beijing from other parts of the country stood in the square or on a street corner, giving speeches day after day until their throats grew hoarse and they lost their voices. Their audience — whether wizened old men or mothers with babies in their arms — nodded repeatedly and applauded warmly, however immature the students” faces or naïve their views.”

When I made a trip to my home in Zhejiang at the end of May, I had no idea when the protests would end. But I took the train back on the

Chai Ling in 1989 afternoon of June 3, and as I woke the next morning on our approach to Beijing, the radio was broadcasting the news that the army was now in Tiananmen Square. The protests quickly subsided amid the gunfire. Students began to abandon Beijing in droves. When I left for the station again on June 7, there was hardly a pedestrian to be seen, only smoke rising from some charred vehicles and — as my classmates and I crossed an overpass — a tank stationed there, its barrel pointing menacingly at us.”

By that time a train in Shanghai had been set on fire and service between there and Beijing had been suspended, so my plan was to take a roundabout route to Zhejiang. I have never in my life traveled on such a crowded train. The compartment was filled with college students fleeing the capital, and there was not an inch of space between one person and the next.”

An hour out of Beijing, I needed to go to the toilet. But the toilet itself was full of people “We can’t get the door open! they shouted back. I had to hold on for the full three hours until we got to Shijiazhuang. There I disembarked and found a pay phone; I appealed for help from the editor of the local literary magazine. Everything’s in such chaos now, he said. Just give up on the idea of going anywhere else. Stay here and write us a story.”

So I spent the next month holed up in Shijiazhuang, but I had a hard time writing. Every day the television repeatedly broadcast shots of students on the wanted list being taken into custody. Far from home, in my cheerless hotel room, I saw the despairing looks on the faces of the captured students and heard the crowing of the news announcers, and a chill went down my spine.”

Then one day, the picture on my TV screen changed completely. The images of detained suspects were replaced by scenes of prosperity throughout the motherland. The announcer switched from passionately denouncing the crimes of the captured students to cheerfully lauding our nation’s progress.”

Tiananmen Generation

Rowena Xiaoqing was born and raised in China. She did some ground-breaking research on the 1989 Tiananmen democracy movement and teaches a freshman seminar related to Tiananmen Square at Harvard. She told the New York Times “Our generation grew up in an atmosphere of idealism. In 1989, I joined students across the country and participated in demonstrations in Guangdong Province. We took to the streets not because of hatred and despair, but because of love and hope. The sense of historical responsibility and faith in reform among intellectuals in the 1980s were crushed overnight. June 4 remains a taboo banned from open discussions. We have been bearing this open wound up to the present. June 4 is a watershed and the root of major social problems in China, including cynicism, nationalism and materialism. It’s impossible to understand today’s China without understanding the spring of 1989. [Source: Luo Siling Sinosphere, New York Times, June 21, 2016]

One of her Chinese students told her in the 2010s: “she finally “pushed” her mother to tell the truth. Her mother had told her she didn’t know anything about 1989. My student asked, “But you were in college then, and my teacher said that students would know.” It turned out that her mother had taken a train to Beijing and gone to Tiananmen Square. Her boyfriend at the time, who is now this student’s father, was locked at home by his own father and couldn’t go. So her mother was in Tiananmen Square in 1989 but told her daughter that she didn’t know anything about it.

“In the 1980s, being critical of the government and pushing for reform were considered patriotic. How has it that patriotism has turned into defending the government, and criticizing it is interpreted as treason? Where did these opposite understandings of “patriotism” come from? Those were the questions that prompted me to start my project on student nationalism in post-Tiananmen China.

“After the June 4 crackdown, the state needed to re-establish its legitimacy. The “patriotic education” campaign, working within a historical vacuum, seems to have been effective. But it is precisely these values that hold that human life, human dignity and human rights can be sacrificed for prosperity and power that have turned post-’89 China into a society with no bottom line and no trust. The distortion of history is accompanied by distortions of all kinds — political, social, psychological. Such values, stopping at nothing for its goals, have not only affected China, but the world.

Atmosphere at Tiananmen Square: Like a Chinese Woodstock?

Chai Ling in 2010

Jeroen den Hengst, a Dutch Sinologist and musician, said : “I lived in Beijing throughout 1987-1988 and then went back in 1989. The liberal politician Hu Yaobang died in April 1989 and everyone mourned his death because he was a reformer who inspired people — he was, amongst others, against corruption. He was very popular amongst Chinese students. University students in Beijing went through the city in a procession to honour him and then the slogans started coming against corruption. It became political very quickly.” [Source: Manya Koetse, What's On Weibo, April 12, 2016]

“We were staying at the Peking University campus, and saw more and more trucks coming and going with students hopping on to go to Tiananmen Square. If I had to compare it with anything, I’d say it was like Woodstock — a bizarre hopeful and loving vibe was capturing Beijing. I absolutely loved it, and I was one of the hundred-thousands of people standing on Tiananmen. We would go there all the time, also in the middle of night, and all my friends from the music scene would also be there to provide entertainment to the students who stayed there.”

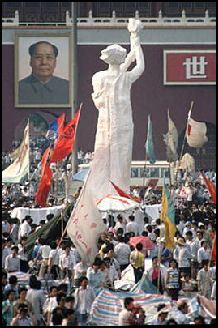

“Cui Jian’s Tiananmen performance was legendary. His songs also made sense, singing about ‘I’ve got nothing to my name’ [see song translation]; he voiced the feelings many had the time. But there were a lot more people there who made music, there were many from the art and music scene. Students were even setting up a Statue of Liberty on Tiananmen. It was one big party.”

“At a certain point I realised that things were going the wrong way; things started to get dirty, literally, and I was too caught up — although I wasn’t politically involved at all. It was just that there were many cute girls and it was all so rock ’n roll, and I enjoyed it, but I got it all wrong. People started getting tired and not much was really happening. The height of the moment was gone. The same familiar faces were appearing in the media and the atmosphere changed. We decided to go to Shanghai by the end of May.

“It was one night in Shanghai, on June 4th, that there was a quiet procession throughout Nanjing Avenue with people carrying big posters. On the trees we saw stapled faxes with images that had gotten through via Hong Kong about what had happened in Beijing. We saw dead people and burnt soldiers. I almost couldn’t believe it — that such a peaceful and care-free time had turned into such a dark thing. We did not return to Beijing afterwards, as we had nothing to do there anymore. People from the Dutch embassy in Beijing went to the campus to collect our photos and films to make sure they were safe. The army had taken over the city. There was no more music, no more nothing.”

Wang Dan in 1989

On his experience at the Tiananmen Square protests, Scott Savitt, a journalist in China in the 1980s and 90s, told the LA Review of Books Blog: “The news blackout in China was broken. The People’s Daily was reporting on the protests. You got a glimpse of what a free China might look like. Beijing then, filled with students protesting and locals supporting them, was an upbeat place. The police stopped working and the traffic got better. They said the crime rate went down. I can’t confirm or deny that, but you basically came to realize that this system of repression is not necessary. The Party’s biggest argument is that they make the trains run on time. It’s not enough. [Source: Matthew Robertson LA Review of Books Blog, May 31, 2017, Interview with Scott Savitt]

“That brief flowering, those seven weeks of protest, is still the most amazing experience of my life by far. You felt like sleeping was a waste of time. I lived in that square for those seven weeks of protest. You just couldn’t get enough of it. It was like a big carnival. And when people are so repressed like that, that sudden flowering of freedom is, even now, a perfect time to look back on.

“Just imagine today, a million people gathered in Tiananmen Square saying whatever they want, saying “Fuck the Communist Party.” Of course, it wasn’t that simple. The authorities said the protesters were trying to overthrow the Party, but that wasn’t the focus. The focus was: We don’t want to live in fear. “However, the thing that was truly unexpected was the government’s dawdling. They could have nipped the early protests in the bud immediately, like they had so many times before. They could have stopped the students from marching to Tiananmen the very first night. But they didn’t. This is why I always maintain that it was the impasse at the top of the Party that allowed those protests to go ahead.

Account by Chai Ling, a Leader of the Tiananmen Square Demonstrations

Chai Ling (born 1966) was one of the student leaders in the Tiananmen Square demonstrations. At the time of the event, she said: I think these may be my last words. My name is Chai Ling. I am twenty-three years old. My home is in Shandong Province. I entered Beijing University in 1983 and majored in psychology. I began my graduate studies at Beijing Normal University in 1987. By coincidence, my birthday is April 15, the day Hu Yaobang died. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The situation has become so dangerous. The students asked me what we were going to do next. I wanted to tell them that we were expecting bloodshed, that it would take a massacre, which would spill blood like a river through Tiananmen Square, to awaken the people. But how could I tell them this? How could I tell them that their lives would have to be sacrificed in order to win? If we withdraw from the square, the government will kill us anyway and purge those who supported us. If we let them win, thousands would perish, and seventy years of achievement would be wasted. Who knows how long it would be before the movement could rise again? The government has so many means of repression — execution, isolation. They can wear you down and that's exactly what they did to Wei Jingsheng.

“I love those kids out there so much. But I feel so helpless. How can I change the world? I am only one person. I never wanted any power. But my conscience will not permit me to surrender my power to traitors and schemers. I want to scream at Chinese people everywhere that we are so miserable! We should not kill each other anymore! Our chances are too slim as it is.

See Interview at Tiananmen Square with Chai Ling afe.easia.columbia.edu

Big March of April 27

Tiananmen protestor demanding free speech

Wang Chaohua, a leader of the Tiananmen protests, wrote: “A key early turning point in 1989, when the protest changed from a student movement to a movement of the masses, came on April 27, when a big illegal march took place in Beijing. It was an unprecedented event in the history of the People’s Republic. The immediate cause of the march was a notorious editorial, issued by the Party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, on April 26. Social discontent had been widespread for some time, due to setbacks of the economic reform (including near-run-away inflation in the summer of 1988) and tightened politico-economic control in early 1989 (including reissued grocery coupons and reduced space for political commentary or proposals at the annual National People’s Congress and National Political Consultative Conference). Deploying formulated expressions from the later stage of the Cultural Revolution of the early-to-mid 1970s and full of implied threats of political suppression, the April 26 editorial provoked immediate and strong reactions among city dwellers. It had been almost a whole decade since the Reform started and general reflections on the Cultural Revolution had gone from redressing wrongs to searching for cultural roots and to appealing for democracy and renewed enlightenment. Why, the people wondered, did the government decide to revert to an old sort of rhetoric, just because there had been some student protests? [Source: The China Beat, May 8, 2009, Wang Chaohua is an independent scholar who received her doctorate from UCLA in 2008. She has written political commentaries for periodicals such as the New Left Review, and is the editor of One China, Many Paths.

On the morning of April 26 we had just announced in our first press conference the establishment of the Beijing Association of College Students (BACS, gao zi lian). That afternoon, the municipal Party Committee held a meeting in the Great Hall of People of ten-thousand Party cadres working in the educational sector, the goal of which was to figure out and mobilize support to implement strategies to control the student unrest. In the evening, our newly elected BACS president was put under great personal pressure in his student dorm and forced to issue a cancellation of the planned march for the next day. The authorities without delay drove him to announce the cancellation on major campuses in the wee hours of April 27. Many campuses saw student internal conflicts in varied degrees, caused by the confusion. Yet, students from the biggest campuses in northwest Beijing broke blocked gates and rushed out to the streets. Soon they joined each other to form a considerably huge, mile-long column.”

Most importantly, well before student marchers reached Changan Avenue, the main east-west thoroughfare across central Beijing through Tiananmen Square, the west section of Changan was already completely empty of motor vehicles. Urban residents from all directions came to fill the broad street, climbing up trees, roofs and billboards along the street, and soon become the major force facing the pre-installed police line on the way leading to Tiananmen. It was these people who eventually pushed away lines of police right in front of Zhongnanhai, the residential compound of Deng Xiaoping and other central Party figures, just to the west of the square. When the marchers kept on eastward after passing the Square and along Changan Avenue, supporting bystanders grew rapidly in both number and enthusiastic energy, creating far greater scenes of protest than the then rather exhausted student marchers.”

I was walking on the east stretch of the Second Ring Road by early dusk, when all the sudden public loudspeakers on streetlamp poles started broadcasting, after being silent for years since the late 1970s. They said that the government was ready to initiate public dialogues with people from all walks of society. Students and the masses gathered around all broke into cheers. It was rumored at the time that the Party elderly leaders were shocked by what they saw on monitoring screen inside Zhongnanhai and had to rethink how to deal with the crisis. The previous hawkish line was replaced by a softened approach.”

Impact of the Big March of April 27

replica of the Goddess of Democracy

When the Big March of April 27 took place, on the student side, the newborn student organization was not only very frail, but had also borne the blow of blackmail from the government in advance. Therefore, though the Big March was a surprise success to both students and the government, it was not a victory of Reason as some intellectuals tend to describe it. Nor was it a movement capable of controlling a victorious retreat, as some others suggested. Instead, it was a success brought about largely by the unprecedented support of the great masses of Beijing. It was a collective refusal by the society to go back to the old model of top-down social mobilization and management, formed in the post-1969 Cultural Revolution years. The success of the Big March, therefore, powerfully demonstrates the political nature of the 1989 protest movement, as well as its essential demands for political reform of democratization.”

On the side of the government, how to handle the protest was inevitably entangled in internal power struggles from the start. After Hu Yaobang’s funeral on April 22, Zhao Ziyang, the then General-secretary of the Party, went to visit North Korea, leaving the mess to Party functionaries to be handled in an old fashioned way that led to the issuing of the April 26 Editorial. On the other hand, the turnabout of official policy on the evening of April 27, trailing the success of the Big March, shows that internal discord and uncertainty were already present inside the highest level of the Party leadership. Policymakers were still searching for ways to get out of trouble — if threatening intimidation did not work, then let us try a friendlier face. Following this, then, we saw a number of new moves: partly televised—and, again, unprecedented in the PRC—dialogue between the State Council’s spokesperson and selected students on April 29; a series of talks Zhao Ziyang gave in early May, openly commenting on economic reforms passing the test of market and political reforms the test of democratization; and the unusual permission secured on May 13 by the famous woman journalist Dai Qing to publish on a whole page of the official Guangming Daily a forum’s transcript by leading liberal intellectuals. How could anyone have imagined these new directions had there not been the Big March on April 27? To accuse the students of getting involved in the Party’s internal power struggle after Martial Law was issued on May 20, as if the youngsters uncannily destroyed a wonderful promising future, is an unrealistically optimistic view of the situation before that date.”

Tiananmen Square Participants and Leaders

Many students camped out in tents and makeshift shelters. Workers, street vendors and others joined the protests

Zheng Xuguang, a protest leader and third year university student, who spent some time on the run as a fugitive, said he had no regrets even though he spent several years in jail. “If I had known I would be arrested and become a wanted criminal I definitely would not have become a member of the Beijing protest. “At the time I had no sense of risk. I was interested and thought it was an important event and so I took part.”

The leaders and participants were often self-absorbed and fractious, divided by disagreements over tactics and money. For some it was like a huge party with opportunities for drinking, flirting and sex. After the protests many of the leaders blamed each other for its failure.

Book: "Beijing Coma" by Ma Jian (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2008) is the story of a man who lies in a coma after being shot by a stray bullet during the Tiananmen Square massacre. It explores this divisions that existed within the protesters as well as the forces that drove them.

Hunger Strike and Paint-Filled Balloons

As the Communist Party of China leadership failed to respond to student demands, some of the more radical students organized a hunger strike. The hunger strike was lead by Zhuo Duo, a social scientist at Beijing University, and Taiwanese pop star Hou Dejian, and three other Chinese intellectual to show their solidarity with the students. They pitched their tent next to student headquarters at the Martyr’s Monument.

On May 23, 1989, an auto mechanic from Hunan named Lu Decheng and two other men threw 30 paint-filled balloons at the portrait of Mao at Tiananmen Square. Lu came over 1,000 kilometers to take part in the demonstrations but was spurned by the student leaders. He was imprisoned for over a decade for the stunt and lost his wife and daughter and eventually emigrated to Canada. The incident is he centerpiece of the 2009 book "Egg on Mao" by Denise Chong.

See The May 13 Hunger Strike Declaration (1989) [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

Gorbachev and Tiananmen Square

Gorbachev in 1987

Tim Daiss wrote in Forbes: “On May 15, 1989, nearly a million university students crowded into Tiananmen Square, Beijing’s central square, and spent the night (despite government warnings) to clear the area. According to media reports at the time, the students said they wanted to hold their own welcoming ceremony for Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev, who arrived the same day for the first Chinese-Soviet summit meeting in 30 years. [Source: Tim Daiss, Forbes, May 15, 2016 +/]

“Gorbachev’s welcoming ceremony was hurriedly moved to the airport, in what was an obvious loss of face for the Chinese government. An Associated Press (AP) report said at the time that “the planned ceremony would have been a major embarrassment” to the Chinese leadership. +/

“Reporters and others had just recently arrived in Beijing to cover the Gorbachev arrival – fortunate timing for news hungry Western media but a public relations nightmare for the still authoritarian Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The student protesters kept up daily vigils for nearly three weeks, marching, chanting and demanding more democratic freedom. However, with Western reporters capturing much of the drama for television and newspaper audiences, the authorities had enough.” +/

Cui Jian in Tiananmen Square

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post, “On May 20, 1989, a Chinese singer and guitarist named Cui Jian walked onto the makeshift stage at Tiananmen Square. Thousands of protesters had held the square for weeks; their calls for political and economic reforms had inspired similar protests in dozens of Chinese cities, panicking the Communist Party leadership. The mood, though tense because of the troops surrounding the square, was still hopeful. No one knew that troops were to massacre hundreds of civilians 15 days later. Cui was already in famous in China, where his rock-and-roll attitude had shaken up a staid pop music scene and captured the imaginations of Chinese youth eager for something new and free-spirited. The crowds at Tiananmen were thrilled to receive him. “If you were there, it felt like a big party,” he later told the British newspaper the Independent. “There was no fear. It was nothing like it was shown on CNN and the BBC.” [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

“The singer, ever a showman, wrapped a red blindfold over his eyes, a symbol of both the Communist Party and its attitude toward the problems that, according to the protesters, needed urgent reform. He later wrote in Time, “I covered my eyes with a red cloth to symbolize my feelings. The students were heroes. They needed me, and I needed them.” -\

Cui Jian in 2007

“He sang two songs. “Nothing to My Name,” quickly became an unofficial anthem of the protest movement and, later, a symbol of its tragic defeat. The song, which tells the story of a poor boy pleading with his girlfriend to accept his love though he has nothing, had made him famous three years earlier. Though Cui insists the song has no political meaning, it captured the changing – and politically charged – mood among China’s increasingly activist youth. It conveys disillusionment and dispossession but also a sense of hope: exactly the attitudes that electrified Tiananmen and the similar protests across China. -\

“Back then, people were used to hearing the old revolutionary songs and nothing else, so when they heard me singing about what I wanted as an individual they picked up on it,” he told the Independent, in explaining the success of “Nothing to My Name”. “When they sang the song, it was as if they were expressing what they felt.” At Tiananmen that day, Cui also sang “A Piece of Red Cloth,” a video of which is below (lyrics in English at bottom) and which he called “a tune about alienation” in his Time article. It refers to a red blindfold, like that he wore in his performance, and though the lyrics are vague it certainly sounds like a reference to the Communist Party’s sternly authoritarian rule. Recall that the violent Cultural Revolution had ended in 1977, a decade before he wrote the song; the Party’s totalitarian era was over by 1989 but was not as distant then as it is today. -\

“I was really clear about standing on the students’ side,” Cui told the BBC. “But not everyone liked what I did. Someone said, ‘Get out of the square. Don’t hurt the students’ health – they are very weak.’” He left Tiananmen by June 4, when troops from the 27th Army Group moved in and shot hundreds of civilians, clearing the square and abruptly ending the protest movement in a crackdown that so shook China that censors still forbid even the most oblique reference. But they could never stop people from listening to “Nothing to My Name.” The song is just too popular, even if not all of its listeners still remember its significance.

Cui Jian said he made two visits to the Square during the protests there before playing a four-song set concert. A 24-minute video clip of posted on Internet (http://www.songtaste.com/song/1471086/) shows the concert. The four songs played by Cui Jian and his band are “Once Again From the Top, Rock and Roll on the New Long March, Like a Knife”, and “A Piece of Red Cloth'”. According to one description of the video: “There's a little bit of a tuning problem at the start, but then things get going with an energetic concert that has the listeners singing along to “Once Again From the Top” and “Rock and Roll on the New Long March” (both from the album Rock and Roll on the New Long March).”

“After the second song, there's a bit of disagreement over whether they should be playing at all: one voice is concerned that about the state of the hunger strikers. The crowd disagrees, Cui says, “Most of the hunger strikers are over here,and I've got to be responsible to them.” Then the band launches into “Like aKnife” (which, like the fourth song, was included on the 1991 album Solution.”

“Before the next song, voices in the crowd reassure the band that they're OK with the boisterous music. Cui says, “If there's one student who doesn't want me to perform, I won't; it's about the safety of every person.....I came with about a 20 percent hope of performing, and 80 percent of just coming to see you all.” There are shouted requests for the fourth song, “A Piece of Red Cloth.” Prior to singing, Cui reads off the first verse, and people in the crowd call for everyone who has a piece of red cloth to put it on.”

Crackdown at Tiananmen Square

Things began to get ugly in mid May when protestors began demanding a "dialogue" about democracy, students tried to block streets to prevent the People's Liberation Army troops from moving into the city; and talks broke down between the government and student leaders.

According to documents, widely regarded as authentic, published in the book “The Tiananmen Papers” (Public Affairs, 2001), the massacre at Tiananmen Square occurred because Deng and high ranking Communists were genuinely worried that the demonstration could lead to a mass uprising that would topple the Communist party. The government didn't crackdown on the demonstrators earlier because it didn't want any embarrassing disruptions before or during a historic visit by Gorbachev to Beijing on May 15 to 18.

The Tiananmen Square demonstrations set off a serious debate within the Communist Party leadership, with Li Peng the leader a group of hardliners and Zhao Ziyang the leader of the group of reformers. Deng and a group of powerful ostensibly retired leaders, known as the Elders, stepped in to help resolve the conflict.

In an effort to get Deng to take action, Li Peng said, "Some of the protest posters and the slogans that students shout during the marches are anti-Party and anti-socialist. The spear is now pointed directly at you and the others of the elder generation." Deng response: “This no ordinary student movement. This is a well-planned plot whose real aim is to reject the Chinese Communist Party.”

Image Sources: China News Digest, Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons, Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021