DENG XIAOPING'S ECONOMIC REFORMS

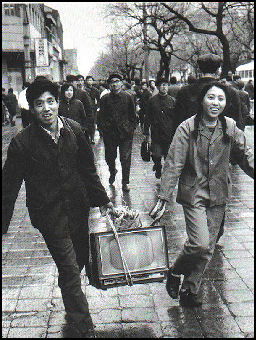

Buying a new TV in the 1980s In 1978, Deng Xiaoping launched what he called a "second revolution" that involved reforming China's moribund economic system and "opening up to outside world." The market-oriented economic reforms launched by Deng were described as "Socialism with Chinese Characteristics." Deng insisted the reforms were not capitalistic: "I have expressed time and again that our modernization is a socialist one," he said.

It has been argued that the Deng reforms were a simple act of pragmatism. The Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s and Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s and early 1970s had left China near bankruptcy and with tens of millions dead. The argument goes that the the Chinese had had enough of radical Communism and Beijing decided that adopting reforms that ran contrary to the fundamental precepts of Communism was the only way for Communism to survive in China. Deng had wanted to make more far-reaching reforms but he was held in check by conservatives that wanted to preserve the Chinese Communist Party’s grip on power.

Deng’s policies have been called “radical pragmatism.” Deng himself called it “crossing the river by feeling for the stones” and the policy in its early stages was called the “the household responsibility system.” The reforms set in motion one of the longest sustained economic expansions in history; three decades of annual growth near 10 percent.

The Deng era is known in China as the Period of Reform and Opening and more recently as the Great Transofrmation. Deng needed great political skill and patience to get his reforms past hard liners in the Chinese Politburo. There was always the belief that the Deng reforms would be reversed at any moment. Deng himself insisted the reforms kept the Communist party from being "toppled."

The Deng reforms decentralized the state economy by replacing central planning with market forces, breaking down the collective farms and getting rid of state-run enterprises. One of the most successful reforms — the "within" and "without” production plans — allowed businesses to pursue their own aims after the met their state-set quotas. Enterprises and factories were allowed to keep profits, use merit pay and offer bonuses and other incentives, which greatly boosted productivity.

In the Deng era there was a shift from central planning and reliance on heavy industry to consumer-oriented industries and reliance on foreign trade and investment. The 1978 reforms included efforts to boost foreign trade through the establishment fo 12 state companies to control imports and exports and the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) along China's southern coastline. In 1982, communes began to be dismantled and peasants were allowed to grow and sell produce. In 1985, tariffs were cut from 56 percent to 43 percent beginning the long, gradual reduction of import barriers.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; AFTER MAO: THE RISE OF DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S LIFE factsanddetails.com; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING STEPS UP HIS ECONOMIC REFORMS: SEZS AND HIS SOUTHERN TOUR factsanddetails.com; ECONOMIC HISTORY AFTER DENG XIAOPING Factsanddetails.com/China

Good Websites and Sources on Deng Xiaoping: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; CNN Profile cnn.com ; New York Times Obituary; China Daily Profile chinadaily.com. ; Wikipedia article on Economic Reforms in China Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Special Economic Zones Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Deng Xiaoping “Deng Xiaoping and China's Economic Miracle” by Rene Schreiber Amazon.com; “China Under Deng Xiaoping: Political and Economic Reform” by John; David Watkin & G.Tilman Mellinghoff Summerson, illustrated Amazon.com; “Idealogy and Economic Reform Under Deng Xiaoping 1978-1993" by Wei-Wei Zhang Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life” by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: My Father" by Deng Maomao (1995, Basic Books) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991" by Xiaoming Zhang Amazon.com; “The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994" by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping" by Richard Baum (1996, Princeton University Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Chronicle of an Empire" by Ruan Ming (1994, Westview Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China" by Richard Evans 1993 Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman" edited by David Shambaugh (1995, Clarendon Paperbacks) Amazon.com; "The New Emperors: Mao and Deng — a Dual Biography" by Harrison E. Salisbury (1992, HarperCollins) Amazon.com After Mao “China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower” by Frank Dikötter, Daniel York Loh, et al. Amazon.com; “Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982" by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; "The Penguin History of Modern China" by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com; “The Search for Modern China” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com

Implementation of Deng’s Economic Policies

handicrafts workshop in Jiangsu in 1983

During the 1980s there was a gradual process of economic reforms, beginning in the countryside, where there was a limited return to a market economy for farm goods. The reforms were very effective and the economy in the countryside began to prosper. As the rural standard of living rose, reforms of the more complex urban economy began. In the mid-1980s, China began to move away from a socialist system of central planning to a market economy. Around the same time, China began to open its economy to the outside world and to encourage foreign investment and joint ventures between China and foreign companies. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Under Deng, pragmatic leadership emphasized economic development and renounced mass political movements. At the all-important December 1978 Third Plenum (of the 11th Party Congress Central Committee), the leadership adopted economic reform policies that included expanding rural incentives to generate income there, encouraging experiments in the market economy and reducing central planning. The plenum also decided to accelerate the pace of legal reform, culminating in the passage of several new legal codes by the National People's Congress in June 1979. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: “In 1980, Zhao Ziyang, a protégé of Deng Xiaoping, replaced Hua Guofeng as premier, and Hu Yaobang, another Deng protégé, became general secretary of the CCP while Hua resigned as party chairperson (a position which was abolished) in 1981. The 1980s saw a gradual process of economic reforms, beginning in the countryside with the introduction of the household responsibility system to replace collective farming. Reforms of the more complex urban economy included, with varying degrees of success, reforms of the rationing and price system, wage reforms, devolution of controls of state enterprises, legalization of private enterprises, creation of a labor market and stock markets, the writing of a code of civil law, and banking and tax reforms. Part of the policy to open up to the outside world including the establishment of Special Economic Zones. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Social Forces Behind the Deng Reforms

James Griffiths of CNN wrote: “By 1978, Deng would be paramount leader, as he and his supporters oversaw the reversal of Cultural Revolution policies and the official opening up of China's economy. While Deng is often given credit for turning China from a collectivist, Communist economy into the powerhouse it would become, according to Dikotter, Deng's reforms were a reflection of those forced upon the country from the bottom up, by a populace alienated to and despairing of Communism. [Source: James Griffiths, CNN, May 13, 2016 /^]

"For the vast majority of the people in the countryside, the credibility of the Communist Party was damaged already during the Great Leap Forward," he says. "When the organization of the Party is damaged by the Cultural Revolution, there's very little left in the countryside to believe in.” Throughout the country, people began setting up markets and exchanges. They "undermine the planned economy and force Deng Xiaoping to abandon it.” This economic reform, driven by the very people who were most abused by Communist rule, would see millions of Chinese lifted from poverty and change the country forever.

In their book, "China’s Megatrends: The Eight Pillars of a New Society", futurologist John Naisbitt and his wife Doris argue that China liberated itself from its Maoist ideological mindset and reactivated China’s “entrepreneurial gene” when Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1978.” On China’s fundamental transformation between the Cultural Revolution and the present the Naisbitts wrote: “China in 1978: A visionary, decisive, assertive CEO takes over a very large, moribund company that is on the verge of collapse. The workforce is demoralized, patronized, and poorly educated. The CEO is determined to turn the run-down enterprise into a healthy, profitable, sustainable company, and to bring modest wealth to the people. And he has a clear strategy for achieving this goal.” China in 2009: The company has changed from an almost bankrupt state into a very profitable enterprise, the third largest of its kind in the world. It has made clever moves in its challenges and crisis, and its economic success is now recognized around the globe.” [Source: William A. Callahan, China Beat, November 15, 2010, William A. Callahan is Professor of International Politics at the University of Manchester and author of China: The Pessoptimist Nation (Oxford University Press, 2010)]

Rural Industry Tradition in China

Ken Pomeranz and Bin Wong wrote: “Reform-Era China Draws on the Past: As many people know, beginning in the 1980s and well into the 1990s, the main source of economic dynamism in reform-era China came from the development of township and village enterprises, from enterprises that existed in small towns and in villages and involved people who previously were in farming.Why was the development of rural industry a smart strategy in this period? One of the reasons has to do with earlier patterns of economic activity where handicraft production was largely in the countryside. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“This is to say that because the Chinese did not have the same pattern of urbanization and the development of urban industry as Europe did, it made sense that the development of new industrial opportunities in China in the 1980s took advantage of certain kinds of spatial and institutional patterns that drew upon older forms of economic activity, older forms of marketing, older forms of networking between peoples in different villages. Many of these resources tapped into the development of township and village enterprises. Now clearly, the development of township and village enterprises in the 1980s depended on a lot of factors. It depended on new technologies becoming available, as well as new sources of capital. And rural industrialization took place in an institutional environment that was very different from what had existed 200 years earlier.

“All of that is clearly true. But what is missing in most accounts that look at township and village enterprise with an historical perspective going back to the 1950s at most is a recognition that rural industry and rural commerce called upon traditions that went back to much earlier periods in a positive way. Therefore, the success of the development of township and rural enterprises, in my opinion, depended at least in part on the repertoire of practices and possibilities that Chinese in the countryside have had for a long time. This then means that the past is not simply an obstacle. It is not simply something negative. The past includes practices that people can harness to serve new kinds of goals.

Zhao Ziyang and the Deng Economic Reforms

In the memoir, Zhao Ziyang presses the case that he pioneered the opening of China’s economy to the world and the initial introduction of market forces in agriculture and industry — steps he says were fiercely opposed by hard-liners and not always fully supported by Deng, the paramount leader, who is often credited with championing market-oriented policies.[Source: Erik Eckholm, New York Times, May 14, 2009]

Adi Ignatius, an editor of a book on Zhao and editor in chief of the Harvard Business Review, wrote in Time, “Although Deng generally gets credit for modernizing China’s economy, it was Zhao who brought about the innovations — from breaking up Mao’s collective farms to creating special economic zones...And it as Zhao who had to continually outflank powerful rivals who didn’t want to see the system change.”

Zhao Ziyang In the late 1970s, as the party chief in Sichuan Province, Zhao had started dismantling Maoist-style collective farms. Deng, who had just consolidated power after Mao’s death, brought him to Beijing in 1980 as prime minister with a mandate for change. Zhao, who like other Chinese leaders had little training in or experience of market economics, describes his political battles and missteps as he tried to give more reign to free enterprise. [Source: Erik Eckholm, New York Times, May 14, 2009]

Roderick MacFarquhar, a China expert at Harvard, said Zhao’s memoirs gave him a new appreciation of Zhao’s centralrole in devising economic strategies, including some, like promoting foreign trade in coastal provinces, that he had urged on Deng, rather than the other way around. Deng Xiaoping was the godfather, but on a day-to-day basis Zhao was the actual architect of the reforms, MacFarquhar said. Bao Tong, Zhao's former aide, told Reuters his boss "would go to factories and villages" and ask them whether they had any problems. "He focused on these problems, not on how you can help develop Marxism."

In the early “80s writer Hu Yua was working as a dentist in a small town between Shanghai and Hangzhou. From his window he often observed workers of the local Cultural Bureau, the Chinese state’s salaried writers and artists, loafing in the streets. We were all very poor in those days, Yu recalled. The difference was that you could work hard to be poor as a dentist, or you could do nothing and still be poor as a worker in the Cultural Bureau. I decided I wanted to be as idle as the workers in the Cultural Bureau and become a writer. [Source: Pankaj Mishra, New York Times, January 23, 2009]

Zhao Ziyang on His Impact on the Deng Economic Reforms

Zhao wrote in his memoirs, “The reason I had such a deep interest in economic reform and devoted myself to finding ways to undertake this reform was that I was determined to eradicate the malady of China’s economic system at its roots. Without an understanding of the deficiencies of China’s economic system, I could not possibly have had such a strong urge for reform.” [Source: Zhao Ziyang’s "Prisoner of the State"]

Of course, my earliest understanding of how to proceed with reform was shallow and vague. Many of the approaches that I proposed could only ease the symptoms; they could not tackle the fundamental problems. The most profound realization I had about eradicating deficiencies in China’s economy was that the system had to be transformed into a market economy, and that the problem of property rights had to be resolved. That was arrived at through practical experience, only after a long series of back-and-forths.”

But what was the fundamental problem” In the beginning, it wasn’t clear to me. My general sense was only that efficiency had to be improved. After I came to Beijing, my guiding principle on economic policy was not the single-minded pursuit of production figures, nor the pace of economic development, but rather finding a way for the Chinese people to receive concrete returns on their labor. That was my starting point. Growth rates of 2 to 3 percent would have been considered fantastic for advanced capitalist nations, but while our economy grew at a rate of 10 percent, our people’s living standards had not improved.”

As for how to define this new path, I did not have any preconceived model or a systematic idea in mind. I started with only the desire to improve economic efficiency. This conviction was very important. The starting point was higher efficiency, and people seeing practical gains. Having this as a goal, a suitable way was eventually found, after much searching. Gradually, we created the right path.”

Starting the Deng Economic Reforms

Zhao Ziyang in Berlin in 1987 Deng’s economic reforms first really took hold in the countryside where peasants were encouraged to participate in the market economy. Communes and collectives were dismantled and were divided up into plots of land that was leased back to peasants who were encouraged to raise crops to sell in private markets.

Even with his firm grip on power, it was difficult for Deng to start China's economic reform process . Nearly every step was a hard struggle. In his memoir, Zhao Ziyang wrote, “It was not easy for China to carry out the Reform and Open-Door Policy. Whenever there were issues involving relationships with foreigners, people were fearful, and there were many accusations made against reformers: people were afraid of being exploited, having our sovereignty undermined, or suffering an insult to our nation. I pointed out that when foreigners invest money in China, they fear that China’s policies might change. But what do we have to fear” [Source: Zhao Ziyang’s "Prisoner of the State; Erik Eckholm, New York Times, May 14, 2009]

Zhao wrote, “In summary, there were two aspects: one was the market economic sector outside of the planning system, and the other was the planned economic sector. While expanding the market sector, we reduced the planned sector. While both planned and market sector existed, it was inevitable that as one grew the other shrank. As the planned sector was reduced and weakened, the market sector expanded and strengthened.”

At the time, the major components of the market sector were agriculture, rural products, light industries, textiles, and consumer products. Products involved with the means of production were mostly still controlled by state-owned enterprises.”

If the enterprises that controlled the means of production were not weakened or reduced, if a portion was not taken out to feed the market sector, growth could not continue for the emerging market economic sector. If no part of the means of production was allowed to be directly sold on the free market; for example, if small enterprises producing coal or concrete were all under central control; then the new emerging market sector would have run into great difficulties for lack of raw materials and supplies. Therefore, for more than ten years, though there was no fundamental change to the planned economic system and the system of state-owned enterprises, the incremental changes in the transition from planned to market economies had an undeniably positive effect.”

Of course, it is possible that in the future a more advanced political system than parliamentary democracy will emerge. But that is a matter for the future. At present, there is no other.”

Based on this, we can say that if a country wishes to modernize, not only should it implement a market economy, it must also adopt a parliamentary democracy as its political system. Otherwise, this nation will not be able to have a market economy that is healthy and modern, nor can it become a modern society with a rule of law. Instead it will run into the situations that have occurred in so many developing countries, including China: commercialization of power, rampant corruption, a society polarized between rich and poor.”

See Separate Article AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com

Zhao on the Ideology Behind the Deng Reforms

Zhao Ziyang with Reagan Zhao wrote in his memoirs, “We had practiced socialism for more than thirty years. For those intent on observing orthodox socialist principles, how were we to explain this” One possible explanation was that socialism had been implemented too early and that we needed to retrench and reinitiate democracy. Another was that China had implemented socialism without having first experienced capitalism, and so a dose of capitalism needed to be reintroduced. [Source: Zhao Ziyang’s “Prisoner of the State”]

Neither argument was entirely unreasonable, but they had the potential of sparking major theoretical debates, which could have led to confusion. And arguments of this kind could never have won political approval. In the worst-case scenario, they could even have caused reform to be killed in its infancy.”

While planning for the 13th Party Congress report in the spring of 1987, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to resolve this issue. I came to believe that the expression initial stage of socialism was the best approach, and not only because it accepted and cast our decades-long implementation of socialism in a positive light; at the same time, because we were purportedly defined as being in an initial stage, we were totally freed from the restrictions of orthodox socialist principles. Therefore, we could step back from our previous position and implement reform policies more appropriate to China.”

Stages of the Deng Reforms

Deng had a “three-step” plan for China: 1) step one, double GDP from 1981 to 1990 and ensure enough food and shelter for all people; 2) step two, double GDP again in the 1990s and make sure people live a moderately prosperous life; and 3) step three, achieve modernization by 2050 by raising incomes to the levels of medium-size developed countries.

Deng launched the reforms with the words: “only development makes sense.” China’s approach was defined by carefully controlled reform, a strategy once described by the late Communist Party patriarch Chen Yun as “crossing the river by feeling for the stones.” (It is wrongly credited to Deng Xiaoping most of the time.)

Daily life in much of China Deng’s “reform and opening” policy was approved by the party elite at the same party meeting in December 1978 in which his rival Hua Guofeng was ousted and Deng became the de facto leader of China. Launched two years after Mao’s death when China was still emerging from the Cultural Revolution, the policy opened the way for perhaps the most astonishing economic turnaround in human history.

Gradualism, successful integration into the world economy, high levels of growth and investment and a trial and error approach to policy have all contrubuted to China's growth and success. The first special economic zone (SEZ) was established in Shenzhen in 1980. Wary of a rival power bases in economically powerful Shanghai, Deng chose the extreme south to launch his reforms and economic experiments.

In 1986, Deng promoted the “open door” policy to encourage foreign investment. At the time spiraling inflation and corruption limited the amount of foreign investments and money that flowed in.

Fang Lizhi wrote in the New York Review of Books, “Beginning in the 1980s, tens of millions of migrant workers from the countryside crowded Chinese cities to sell their labor in construction, sanitation, and other menial tasks. They were the bedrock that made Deng’s “economic miracle” possible.

China’s First Business License

In 1979, the first business license in China was given to Zhang Huamei a 19-year-old daughter of workers in a state umbrella factory who illegally sold trinkets from a table, who wanted to conduct her business legally. A few years earlier just seeking such a license would have earned her the label of “capitalist roader,” possibly making her a target of Red Guards attacks. Unable to obtain such a license in her home town she traveled 480 kilometers to Wenzhou, a region of China with a tradition of entrepreneurship. [Source: Jonathan Margolis, Times of London, January 2010]

Zhang is now a dollar millionaire and head of the Huamei garment Accessory Company, a supplier of many of the world’s buttons. Looking back on her early years as a pioneering entrepreneur she told the Times of London, “My classmates were ashamed of me for starting my own business. They would turn their heads away when passing my house and pretend not to know me.” On her first sale she said, “the first thing I sold was a toy watch. It was a sunny morning in May 1978, I bought it for 0.15 yuan and sold it for .20. I was very, very excited to make a profit. But I was also very nervous and very afraid the local government staff would come to stop it.”

Soon she expanded into ferry trips to Shanghai, needles, thread, elastic, buttons and was able to make two yuan a day, ten times the state wage. When officials first came to her house she feared the worst but was told what she was doing was alright in light of new reforms. The official said all she needed to do was fill out some forms and provide two photos and she could be legitimate, She was still hesitant, worried about what would happen if the policy changed and she was an record as being a capitalist.

Growth of Retail Sales in the Post-Mao Era

China in 1982

Retail sales in China changed dramatically in the late 1970s and early 1980s as economic reforms increased the supply of food items and consumer goods, allowed state retail stores the freedom to purchase goods on their own, and permitted individuals and collectives greater freedom to engage in retail, service, and catering trades in rural and urban areas. Retail sales increased 300 percent from 1977 to 1985, rising at an average yearly rate of 13.9 percent — 10.5 percent when adjusted for inflation. In the 1980s retail sales to rural areas increased at an annual rate of 15.6 percent, outpacing the 9.7-percent increase in retail sales to urban areas and reflecting the more rapid rise in rural incomes. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The number of retail sales enterprises also expanded rapidly in the 1980s. In 1985 there were 10.7 million retail, catering, and service establishments, a rise of 850 percent over 1976. Most remarkable in the expansion of retail sales was the rapid rise of collective and individually owned retail establishments. Individuals engaged in businesses numbered 12.2 million in 1985, more than 40 times the 1976 figure. *

In 1987 most urban retail and service establishments, including state, collective, and private businesses or vendors, were located either in major downtown commercial districts or in small neighborhood shopping areas. The neighborhood shopping areas were numerous and were situated so that at least one was within easy walking distance of almost every household. They were able to supply nearly all the daily needs of their customers. A typical neighborhood shopping area in Beijing would contain a one-story department store, bookstore, hardware store, bicycle repair shop, combined tea shop and bakery, restaurant, theater, laundry, bank, post office, barbershop, photography studio, and electrical appliance repair shop. The department stores had small pharmacies and carried a substantial range of housewares, appliances, bicycles, toys, sporting goods, fabrics, and clothing. Major shopping districts in big cities contained larger versions of the neighborhood stores as well as numerous specialty shops, selling such items as musical instruments, sporting goods, hats, stationery, handicrafts, cameras, and clocks. *

Supplementing these retail establishments were free markets in which private and collective businesses provided services, hawked wares, or sold food and drinks. Peasants from surrounding rural areas marketed their surplus produce or sideline production in these markets. In the 1980s urban areas also saw a revival of "night markets," free markets that operated in the evening and offered extended service hours that more formal establishments could not match. *

In rural areas, supply and marketing cooperatives operated general stores and small shopping complexes near village and township administrative headquarters. These businesses were supplemented by collective and individual businesses and by the free markets that appeared across the countryside in the 1980s as a result of rural reforms. Generally speaking, a smaller variety of consumer goods was available in the countryside than in the cities. But the lack was partially offset by the increased access of some peasants to urban areas where they could purchase consumer goods and market agricultural items. *

Rationing and Pricing in the Mao and Post-Mao Eras

A number of important consumer goods, including grain, cotton cloth, meat, eggs, edible oil, sugar, and bicycles, were rationed during the 1960s and 1970s. To purchase these items, workers had to use coupons they received from their work units. By the mid-1980s rationing of over seventy items had been eliminated; production of consumer goods had increased, and most items were in good supply. Grain, edible oil, and a few other items still required coupons. In 1985 pork rationing was reinstated in twenty-one cities as supplies ran low. Pork was available at higher prices in supermarkets and free markets. [Source: Library of Congress *]

“As a result of the economic reform program and the increased importance of market exchange and profitability, in the 1980s prices played a central role in determining the production and distribution of goods in most sectors of the economy. Previously, in the strict centrally planned system, enterprises had been assigned output quotas and inputs in physical terms. Now, under the reform program, the incentive to show a positive profit caused even state-owned enterprises to choose inputs and products on the basis of prices whenever possible. State-owned enterprises could not alter the amounts or prices of goods they were required to produce by the plan, but they could try to increase their profits by purchasing inputs as inexpensively as possible, and their off-plan production decisions were based primarily on price considerations. *

“Prices were the main economic determinant of production decisions in agriculture and in private and collectively owned industrial enterprises despite the fact that regulations, local government fees or harassment, or arrangements based on personal connections often prevented enterprises from carrying out those decisions. Consumer goods were allocated to households by the price mechanism, except for rationed grain. Families decided what commodities to buy on the basis of the prices of the goods in relation to household income. *

Consumer Goods in the Mao and Post-Mao Eras

As with food supplies and clothing, the availability of housewares went through several stages. Simple, inexpensive household items, like thermoses, cooking pans, and clocks were stocked in department stores and other retail outlets all over China from the 1950s on. Relatively expensive consumer durables became available more gradually. In the 1960s production and sales of bicycles, sewing machines, wristwatches, and transistor radios grew to the point that these items became common household possessions, followed in the late 1970s by television sets and cameras. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In the 1980s supplies of furniture and electrical appliances increased along with family incomes. Household survey data indicated that by 1985 most urban families owned two bicycles, at least one sofa, a writing desk, a wardrobe, a sewing machine, an electric fan, a radio, and a television. Virtually all urban adults owned wristwatches, half of all families had washing machines, 10 percent had refrigerators, and over 18 percent owned color televisions. Rural households on average owned about half the number of consumer durables owned by urban dwellers. Most farm families had 1 bicycle, about half had a radio, 43 percent owned a sewing machine, 12 percent had a television set, and about half the rural adults owned wristwatches. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Deng poster, Landsberger; Market, Nolls China website; buying a TV, Ohio State University

Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021