FOREIGN POLICY UNDER DENG XIAOPING

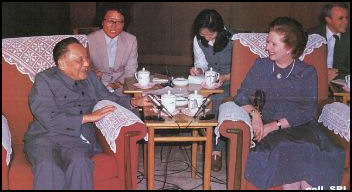

Hong Kong handover

Chinese foreign policy under Deng Xiaoping was shaped by the Deng dictum “hide you ambitions and disguise your claws” which was taken to mean that China should devote its energy to developing economically and not concern itself so much with international affairs. Even so Deng also improved relations with Russia, Japan and South Korea and presided over the handover of Hong Kong. He was the one that ordered the incursion into Vietnam in 1979 with disastrous results. In 1980, the People's Republic took Taiwan's place in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

In 1979, two years after Deng took power, China forged formal diplomatic relations with the United States, engaged in a border war between China and Vietnam and decided not to extend the thirty-year-old Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance with the Soviet Union. All these events led to some criticism of Deng Xiaoping, who had to alter his strategy temporarily while directing his own political warfare against Hua Guofeng and the leftist elements in the party and government. As part of this campaign, a major document was presented at the September 1979 Fourth Plenum of the Eleventh National Party Congress Central Committee, giving a "preliminary assessment" of the entire thirty-year period of Communist rule. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Declaring a policy of "One Country, Two Systems," China reached agreements with both Great Britain (1984) and Portugal (1987) to return to Chinese sovereignty the territories of Hong Kong (in 1997) and Macao (in 1999). Hong Kong had been controlled by Britain since the 1840s and Macau had been a Portuguese colony since the 16th century. The brief border war with Vietnam was over Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia. Except for that China has generally been able to maintain peaceful foreign relations in order to further advance its domestic agenda. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations”: “In the 1980s and 1990s, China attempted to settle its relations with neighboring states. In May 1989, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev visited Beijing in the first Sino-Soviet summit since 1959. Top Vietnamese leaders came to China in 1991, normalizing relations between the two countries after a gap of 11 years. In the early 1990s, China and South Korea established regular relations, with China also maintaining a relationship with North Korea. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

with Carter Perry Anderson wrote in the London Review of Books: Not agrarian reform, by any measure the most beneficial single change for the people of China in the 1980s, but the Open Door becomes Deng’s greatest achievement — its very name a welcome embrace of the slogan with which the US secretary of state John Hay bid for a slice of the Chinese market after the American conquest of the Philippines. Or, as Vogel puts it in today’s boilerplate: “Under Deng’s leadership, China truly joined the world community, becoming an active part of international organisations and of the global system of trade, finance and relations among citizens of all walks of life.” Indeed, he reports with satisfaction, “Deng advanced China’s globalisation far more boldly and thoroughly than did leaders of other large countries like India, Russia and Brazil.” Understandably, pride of place in this progress is given to Deng’s trip to the US, which occupies the longest chapter in the annals of 1977-79. [Source: Perry Anderson, London Review of Books, February 9, 2012]

Deng was in power when the Soviet Union collapsed. Wen Liao, chairwoman of the Longford Advisors, wrote, “From China’s standpoint...the Soviet collapse was the greatest strategic gain imaginable. At a stroke, the empire that gobbled up Chinese territories for centuries vanished. The Soviet military threat...was eliminated. China’s new assertiveness suggests it will not allow Russia to forge a de facto Soviet reunion and thus undo the post-Cold War set.”

Good Websites and Sources on Deng Xiaoping: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; CNN Profile cnn.com ; New York Times Obituary; China Daily Profile chinadaily.com. ; Wikipedia article on Economic Reforms in China Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Special Economic Zones Wikipedia ;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; AFTER MAO: THE RISE OF DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S LIFE factsanddetails.com; CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING: POLICIES, SPEECHES, SLOGANS AND POLITICS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Deng Xiaoping "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life” by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: My Father" by Deng Maomao (1995, Basic Books) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991" by Xiaoming Zhang Amazon.com; “The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994" by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping" by Richard Baum (1996, Princeton University Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Chronicle of an Empire" by Ruan Ming (1994, Westview Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China" by Richard Evans 1993 Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman" edited by David Shambaugh (1995, Clarendon Paperbacks) Amazon.com; "The New Emperors: Mao and Deng — a Dual Biography" by Harrison E. Salisbury (1992, HarperCollins) Amazon.com After Mao “China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower” by Frank Dikötter, Daniel York Loh, et al. Amazon.com; “Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982" by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; "The Penguin History of Modern China" by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com; “The Search for Modern China” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com

Deng and the War Between China and Vietnam in 1979

Perry Anderson wrote in the London Review of Books: China’s war on Vietnam in 1979 is seen by Harvard historian Ezra Vogel and Henry Kissinger as Deng’s resolute action to thwart Vietnamese plans to encircle China in alliance with the USSR, invade Thailand, and establish Hanoi’s domination over South-East Asia. The effort was not popular with many of of Deng’s colleagues and was previewed by Deng’s tour of Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore to ensure diplomatic cover for the attack he was planning, from the war itself, and Deng’s far more important tour of the United States two months later. Deng launched the war just five days after getting back from Washington with the US placet in his pocket. [Source: Perry Anderson, London Review of Books, February 9, 2012]

Lee Kuan Yew, an ardent supporter of the war, has told the world: “I believe it changed the history of East Asia.” Kissinger has suggested that China’s war on Vietnam was a vital blow against the Soviet Union and a stepping-stone to victory in the Cold War. Kissinger said Deng’s masterstroke required US “moral support”. “We could not collude formally with the Chinese in sponsoring what was tantamount to overt military aggression,” Brzezinski explained. Kissinger’s said: “Informal collusion was another matter.”

Militarily, the war was a fiasco. Deng threw 11 Chinese armies or 450,000 troops, the size of the force that routed the US on the Yalu in 1950, against Vietnam, a country with a population a twentieth that of China. As the chief military historian of the campaign, Edward O’Dowd, has noted, “in the Korean War a similar-sized PLA force had moved further in 24 hours against a larger defending force than it moved in two weeks against fewer Vietnamese.” So disastrous was the Chinese performance that all Deng’s wartime pep talks were expunged from his collected works, the commander of the air force excised any reference to the campaign from his memoirs, and it became effectively a taboo topic thereafter.

See Separate Article 1979 CHINA-VIETNAM BORDER WAR factsanddetails.com

with Thatcher

China and the Pol Pot Regime

Dan Levin of the New York Times wrote: “In Cambodia, a small band of historians has been clamoring for Beijing to acknowledge its role in one of the worst genocides in recent history. In the 1970s, Mao wanted a client state in the developing world to match the Cold War influence of the United States and the Soviet Union. He found it in neighboring Cambodia. “To regard itself as rising power, China needed that type of accessory,” Andrew Mertha, author of “Brothers in Arms: China’s Aid to the Khmer Rouge, 1975-1979,” said in an interview. [Source: Dan Levin, Sinosphere, New York Times, March 3, 2015 ***]

“According to Mr. Mertha, director of the China and Asia-Pacific Studies program at Cornell University, China provided at least 90 percent of the foreign aid given to the Khmer Rouge, from food and construction equipment to tanks, planes and artillery. Even as the government was massacring its own people, Chinese engineers and military advisers continued to train their Communist ally. “Without China’s assistance, the Khmer Rouge regime would not have lasted a week,” he said. ***

In 2010, the Chinese ambassador to Cambodia, Zhang Jinfeng, offered a rare official acknowledgment of China’s support of the Khmer Rouge, but said that Beijing donated only “food, hoes and scythes.” Citing records and testimony from former Khmer Rouge officials, Youk Chhang, a survivor of the genocide and executive director of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, disagreed. “Chinese advisers were there with the prison guards and all the way to the top leader,” Mr. Youk said. “China has never admitted or apologized for this.” ***

Deng's Visits to the United States

In 1974, before he became leader and while Mao was still alive, Deng traveled to New York to address the U.N. General Assembly. It was first time he visited the West since leaving Paris in 1926. During a stopover in Paris he bought a large box of croissants. In New York an aid bought Deng a “doll that could cry, suck and pee”, which proved “a great hit” when he got home, along with the 200 croissants from Paris. Before the trip the West knew very little about Deng. He arrived in New York with a large delegation. As they prepared for the expensive trip, Chinese officials discovered that the could muster only $38,000 in foreign cash. In those days there were no banks in China except the People's Bank of China, then a department of the Ministry of Finance.

China reached a political milestone when formal diplomatic relations were established with the United States on January 1, 1979 when China was under the leadership of Deng. In 1979, Deng became the first Chinese leader to visit the United States. During the trip he chatted with industrialists at cocktail parties and attended performances by John Denver and the Harlem Globetrotters and donned a 10-gallon hat at a rodeo arena in Texas. While visiting a Texas rodeo in 1979, he famously donned a 10-gallon cowboy hat, "to the delight of his hosts, producing an iconic image that helped brighten Americans’ perception of China."

Shannon Tiezzi and Jeffrey Wasserstrom wrote in Slate: “In 1979, when Deng became the first Chinese Communist Party leader to visit the United States, he took pains to make a good impression and seem relatable to American audiences. He shook hands with Harlem Globetrotters, climbed on NASA’s lunar rover, and, most memorably, donned a gigantic cowboy hat at a Texas rodeo, delighting the crowd.” [Source: Shannon Tiezzi and Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Slate, September 24, 2015]

According to the Global Times: “Not just a significant diplomatic event in Chinese history, former country leader Deng Xiaoping’s nine-day visit to the US in 1979 has been recognized as an event that helped reshape the face of global politics at the time. For years questions about his visit such as how he survived an assassination attempt in a foreign country have stirred people’s curiosity over the years. [Source: Global Times, May 14, 2015]

“Attending a total of over 80 major activities, 20 official banquets and 10 news press conferences, Deng barely took a moment to breath during his visit up until he fell ill and suffered from a low fever.” He met with US President Jimmy Carter and former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger amog others. “If we look at that visit through the lens of fashionable Internet thinking today, it was actually the biggest political and commercial road show in history for a financially poor China at the time,” Fu Hongxing, director of a documentary about the trio told the Global Times. “Deng was there to show China’s determination in implementing its opening-up policy. After the road show was over, China got ‘listed’ and even today the country’s ‘marketing value’ is still rising.”

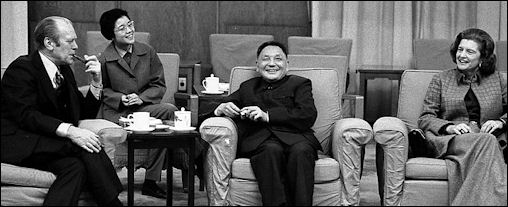

with Gerald and Betty Ford

Reagan’s Trip to China in 1984

“On his visit to China in 1984 with U.S. President Ronald, James Mann of the Los Angeles Times wrote, “We landed in Beijing, at the old airport, on one of those April days when it rains mud. The sky was a pale yellow-orange. The first stop was Tiananmen Square, where, in front of the Great Hall of the People, Reagan went to welcoming ceremonies: the girls waving bouquets and shouting “Huanying,” the 21-gun salute. Some in the White House press corps made a great deal of this reception, interpreting it as an Important Sign of China’s love for America or for Reagan or as an upturn in Sino-American relations. A day later, a reporter living in Beijing, perhaps from one of the wire services, told me the president of some Non-Superpower nation (was it Lesotho? Lichtenstein? Brunei?) had gotten virtually the identical welcoming ceremony, or a warmer one, in the same place the day before Reagan arrived.” [Source: James Mann, hkej.com, April 30, 2011]

“There is usually an attempt before summits like this one to produce some “deliverable,” a specific agreement or series of agreements that can be signed by the two countries,leaders to demonstrate the talks have produced “results.” On Reagan’s trip, the deliverable was a nuclear agreement, signed in Beijing, permitting American technology to go to China; the deal would, it was hoped, open the way for Westinghouse to win the contracts to build Chinese nuclear plants. This was supposed to be the main “news” of Reagan’s trip, and produced numerous front-page stories back home in the United States. Later on, Reagan’s principal agreement in China turned out to be almost meaningless. It required congressional approval. Congress balked at the idea of giving China nuclear technology, because members of Congress...feared that China was helping Pakistan’s nuclear program, and that Pakistan might in turn spread nuclear technology to other countries. (Looking back, I can’t imagine how they could have believed such far-fetched ideas.) As a result, Westinghouse didn’t win those Chinese contracts.”

“Reagan flew down to Shanghai, which in those days lagged far behind Beijing in new construction or new anything. It seemed as if it had been covered in a bell jar for more than a quarter-century. We stayed at the old Jinjiang Hotel, the place where Richard Nixon got drunk on maotai, consuming glass after glass until past two o’clock in the morning, in celebration and relief on his final night in China.”

“One of Reagan’s couple of events in Shanghai was a visit to one of the very first Sino-American joint ventures, the Shanghai Foxboro Co., which was making industrial-control instruments. “Business partnerships between Chinese and American companies are bound to succeed,” Reagan declared with seeming certainty. I wasn’t so sure. To me, the American head of the joint venture, Donald Sorterup, looked frustrated and lost. At the ceremony with Reagan, he admitted that the company’s first year “has not been a totally calm journey.” His evident discombobulation started me to wonder about the dynamics between the American business representatives and their Chinese counterparts. A few years later, this became the subject of my first book, “Beijing Jeep.”“

“Reagan was of course known as America’s most successful anti-Communist politician, but by the time of this trip, it seemed far more accurate to call him anti-Soviet. He clearly wanted to make sure of China’s continuing help and partnership in dealing with the Soviet Union and thus was eager for good relations with China’s Communist regime. In Beijing, he twice reminded Chinese audiences that “America’s troops are not massed on China’s borders.” Both times, China censored those remarks. He kept on trying. In Shanghai, speaking at Fudan University, he denounced the Soviet Union as an “expansionist power.” This time, the speech was carried live, but not translated into Chinese.”

“He did also try to speak briefly about democracy and the values of free speech and freedom of religion, and these remarks, too, were censored. But in general, on Reagan’s China trip, even the most obvious symbols of ideology were ignored or else converted for the audience back home into the terms of American politics, sports, commerce and advertising. Asked by some inquiring reporter whether he had ever been to a Communist country, Reagan’s White House Chief of Staff James Baker replied, “I’ve been to Massachusetts.” A deputy press secretary gave his Chinese counterparts baseball caps he had obtained from Nolan Ryan, then of the Houston Astros, that had red stars on the front. Red star over China—get it?”

“As Reagan was leaving Beijing, his motorcade passed through Tiananmen Square again, where, in preparation for the May Day parade, China had put up large posters of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin. Reagan’s spokesman Larry Speakes said Reagan had seen the posters but belittled their significance. “He thought they were the Smith Brothers,” Speakes said, referring to the bearded men on boxes of American cough drops. Later on, on the flight back over the Pacific, Reagan outdid him with a well-remembered line that again downplayed ideology: He referred to China as “this so-called Communist country.”

August 25, 2021Image Sources: Chinese government (China.org), White House (Biden pictures) and Wikicommons

Text Sources: Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016