TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA

Transport in the old days China has traditionally been a nation of pedestrians, bicycle riders and train and bus takers. In the Mao era there was few traffic problems because there were few motorized vehicles. But recently and in a very short period of time China has advanced from the bicycle stage to the car stage. Roads once filled with bicycles are now filled with cars. Some large highway interchanges have been celebrated on stamps.

Rivers and canals — most notably the Yangtze River and Grand Canal, which more or less connects Shanghai to Beijing — traditionally been the main transportation arteries and remain important today. Since the 1980s China has greatly improved it roads and built many first class major highway and paved roads. More recently it has invested significantly in constructing high-speed rail lines and now has the most extensive high-speed rail system in the world. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Transportation networks have experienced major growth and expansion since 1949 and especially since the early 1980s. Railroads, which are the primary mode of transportation, have doubled in length since the mid-twentieth century, and an extensive network provides sufficient service to the entire nation. Even Tibet with its remote location and seemingly insurmountable terrain has railroad service. The larger cities have subway systems. [Source: Library of Congress]

Much of China, especially the east, is well served by railroads and highways, and there are major rail and road links with the interior. There are railroads to North Korea, Russia, Mongolia, and Vietnam, and road connections to Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Myanmar. In 2000, China boasted about 7,450 miles of expressways. A decade later, it had 40,400 miles, not much smaller than the American system, which it plans to leapfrog by 2020. Growth of China's highway and road has been accompanied by a rapid increase of motor vehicle use.

Some of the motorized vehicles seen on the streets of Beijing look like home-made versions of Thailand’s tuk tuks with an aluminum box to protect users from the weather.

See Separate Articles TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA: SUBWAYS, TAXIS AND RIDE SHARING factsanddetails.com ; BICYCLES IN CHINA: RIDING, SHARING AND MANUFACTURING factsanddetails.com ; TRANSPORTATION IN BEIJING: SUBWAYS, BICYCLES, TAXIS AND ROADS factsanddetails.com; TRAINS. LONG-DISTANCE BUSES AND AIRPORTS IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com; TRANSPORTATION IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com; GUANGZHOU TOURISM, ENTERTAINMENT AND TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com; TRANSPORTATION IN TIBET: MOTORCYCLES, HORSES AND YAK CARAVANS factsanddetails.com; TRAINS IN CHINA: HISTORY, TRAIN LIFE, NEW LINES factsanddetails.com CHINA’S RAILWAY MINISTRY: ITS AMBITIOUS RAIL NETWORK, LIU ZHIJUN AND CORRUPTION factsanddetails.com ; HIGH-SPEED TRAINS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AUTOMOBILES IN CHINA: GROWTH, POPULAR CARS, NUMBERS factsanddetails.com ; DRIVING IN CHINA: CUSTOMS, TESTS AND BAD HABITS factsanddetails.com ; ROADS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE AUTOMOBILE INDUSTRY: HISTORY, IMPROVEMENTS AND EXPORTS factsanddetails.com; ROAD CONGESTION AND TRAFFIC JAMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AIR TRAVEL IN CHINA: HISTORY, GROWTH, AIRPORTS AND INFRASTRUCTURE factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE AIRLINES: HISTORY, BUSINESS AND SERVICE factsanddetails.com ; PLANE CRASHES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com; “Handbook on Transport and Urban Transformation in China” by Chia-Lin Chen, Haixiao Pan, et al. Amazon.com; Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler, Peter Berkrot, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet Transportation” (1991) by Editors: Zhang Ying etc. Amazon.com; “Chinese Junks and Other Native Craft” by Ivon A. Donnelly and Gareth Powell Amazon.com; “The Great Ride of China: One Couple's Two-wheeled Adventure Around the Middle Kingdom” by Buck Perley Amazon.com; “Finding Compassion in China: A Bicycle Journey into The Countryside” by Cindie Cohagan Amazon.com; “Dad's Bicycle: Journey of A Chinese Family” by Helen Wang Amazon.com;

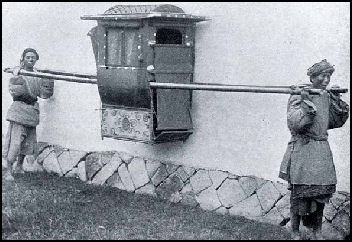

Traditional Forms of Transportation

Some goods are still moved by carts and wagons or pulled by tractors or bicycles. Up until recently most goods in China were transported around the cities of flat bed pedicabs — bicycle versions of a pick-up truck. Horse drawn carts still ply the streets in cities and towns. Three-wheeled tractors with carts are a common form of transportation in rural China.

In 1899, Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: A man from Henan had gathered a stock of goods amounting to more than the value of fifty Mexican dollars, and departed for Manchuria, nearly 1,500 miles distant, in order to learn what had become of his sister’s son who had left home in anger. The goods were disposed of to pay travelling expenses, but the journey of a few months as planned, was lengthened to more than a year. The poor man fell sick, his goods were spent, and he was many months slowly begging his way back, and after all had learned nothing of his nephew. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Describing an incident which occurred in one of the western counties of Shandong, Smith wrote in “Village Life in China” (published in 1899): A party of villagers with flags and a drum were on their way to a temple to pray for rain. They met a man leading a horse, on which was seated a married woman returning from one of the customary visits to her mother’s family. She had a child in her arms, and the hired labourer leading the horse had on a wide straw hat...The peasant was roared at” by a group people praying for rain “and a long pike-staff was thrust into his hat which was thrown from his head upon the horse, which being frightened pulled away and plunged ahead. The woman could not keep her seat, first dropping her child which was dashed to the ground and killed. The woman’s foot caught in a stirrup and she was dragged for a long distance and when the horse was at length stopped she too was dead. She was pregnant, so that in one moment three lives had been sacrificed. The hired man ran on a little way to the woman’s home, told his story, and as the men of the family happened to be at home, they all seized whatever implements they could find and ran after the rain-prayers, with whom they fought a fierce battle killing four or five of them outright. The case went into the District yamên, and what became of it then, we do not know.

Distances in 19th Century China

The li is a traditional Chinese measure of distance. Its length has varied considerably over time but was usually about one third of an English mile and now has a standardized length of a half-kilometer (500 meters or 1,640 feet)

Arthur Henderson Smith wrote in “Chinese Characteristics”: “Besides this, the method of reckoning is frequently based, not on absolute distance, even in a Chinese sense, but on the relative difficulty of getting over the ground. Thus it will be “ninety li" to the top of a mountain, the summit of which would not actually measure half that distance from the base, and this number will be stoutly held to, on the ground that it is as much trouble to go this “ninety li" as it would be to do that distance on level ground. Another somewhat peculiar fact emerges in regard to linear measurements, namely, that the distance from A to B is not necessarily the same as the distance from.B to A! It is vain to cite Euclidian postulates that "quantities which are equal to the same quantity are equal to each other." In China this statement requires to be modified by the insertion of a negative. We could name a section of one of the most important highways in China, which from north to south is 183 li in length while from south to north it is 190 li, and singularly enough, this holds true, no matter how often you travel it, and how carefully the tally is kept! “Akin to this, is another intellectual phenomenon, to wit, that in China it is not true that the "whole is equal to the sum of all its parts." This is especially the case in river travel. [Source:“Chinese Characteristics” by Arthur Henderson Smith, 1894]

“Since this was written, we have met in Mr. Baber's Travels in Western China with a confirmation of the view here taken. “We heard, for instance, with incredulous ears, that the distance between two places depended upon which end one started from; and all the informants separately questioned, would give the same differential estimate. Thus from A to B would -be unanimously be called one mile, while from B to A would, with equal unanimity, be set down as three. An explanation of this offered by an intelligent native was this : Carriage is paid on a basis of so many cash per mile, it is evident that a coolie ought to be paid at a higher rate if the road is uphill. Now it would be very troublesome to adjust a scale of wages rising with the gradients 'of the road. It is much more convenient' for all parties to assume that the road in difficult or precipitous places is longer. This is what has been done and these conventional distances are now all that the traveller will succeed in ascertaining.

“Since this was written, we have met in Mr. Baber's Travels in Western China with a confirmation of the view here taken. “We heard, for instance, with incredulous ears, that the distance between two places depended upon which end one started from; and all the informants separately questioned, would give the same differential estimate. Thus from A to B would -be unanimously be called one mile, while from B to A would, with equal unanimity, be set down as three. An explanation of this offered by an intelligent native was this : Carriage is paid on a basis of so many cash per mile, it is evident that a coolie ought to be paid at a higher rate if the road is uphill. Now it would be very troublesome to adjust a scale of wages rising with the gradients 'of the road. It is much more convenient' for all parties to assume that the road in difficult or precipitous places is longer. This is what has been done and these conventional distances are now all that the traveller will succeed in ascertaining.

' But' I protested; 'on the same principle, wet weather must elongate the road, and it must be farther by night than by day.' ' Very true, but a little extra payment adjusts that.' This system may be convenient for the natives, but the traveller finds it a continual annoyance. The scale of distances is something like this : On level ground, one statute mije is called two li; on ordinary hill roads, not very steep, one mile is called five li; on very steep roads, one mile is called fifteen li. The natives of Yunnan, being good mountaineers, have a tendency to underrate the distance on level ground, but there is so little of it in their country, that the future traveller need scarcely trouble himself with the consideration'. It will be sufficient to assume five local li, except in a very steep places, as being one mile." you ascertain that it is "forty li" to a point ahead. Upon more careful analysis, this "forty" turns out to be composed of two “eighteens," and you are struck dumb with the statement that “four nines are 40, are they not?” In the same manner, “three eighteens" make “sixty," and so on generally. We have heard of a case in which an imperial courier failed to make a certain distance in the limits of time allowed by rule; and it was set up in his defence that the "sixty li" were "large." As this was a fair ptea, the magistrate ordered the distance measured, when it was found that it was in reality “eighty-three li" and it has continued to be so reckoned ever since.

Traveling in Guizhou in the 1900s

Describing a journey by the missionary James R. Adam in Guizhou, Clarke wrote: “Towards the end of July 1908 some of the Miao Christians came in from Ko-pu to escort Mr. Adam back to their district. The missionary party consisted of Mr. Adam, Teacher Tsao, B.A., Evangelist Chin, and nine Miao men. About twelve miles from Anshun they were overtaken by a heavy thunderstorm, and when the rain comes down in Guizhou it knows how to do so. Very soon every member of the party was wet through, and all the bedding and food-baskets were thoroughly soaked. At Tinglan, however, a few miles farther on, was an out-station in a Chinese walled town, where after resting a while and refreshing themselves with tea and cakes they continued their journey. Darkness overtook them before they finished the stage, and after a wearisome climb up steep hills, they put up for the night at a dismal little wayside inn. All the inns are dismal in that part of the country, but some of them superlatively so, and this was one of them. Shelter and rice for the men could be had, but no corn or grass for the ponies, so those tired Miao men, after carrying their loads for nearly thirty miles over mountain roads, quietly stole out and, without letting Mr. Adam know, cut grass on the hill-sides for the animals. It was very late when, after a short service, they lay down to rest. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

Next morning they resumed their journey, and passed through Ta-ngai-chio, a large markettown on the high-road, which would be a good centre for an out-station. While crossing a small stream, the Miao men who carried the food-basket let it fall into the water, so that the bread and everything else in the basket was spoiled. That night they put up at an inn called the “Old Eagles' Nest,'' an airy sort of place, open on all four sides to any wind that might blow. However, they had a roof over their heads and that was something. While the supper was being prepared, the missionary band had an evening service, the subject of their meditations being “ Behold the Lamb of God which taketh away the sin of the world."

The travellers were now getting into the Miao district, and at four o'clock in the morning they were again on the move. They stopped for lunch at a place called “Pig Market," and here fell in with two Miao Christians, carpenters, who were on their way to Heo-er-kuan to make new seats for the chapel. These had lunch with the travellers, and afterwards helped the men to carry their loads. On Monday morning the party resumed their journey and reached HsinJu-fang. On the way, while crossing a swollen river, Mr. Tsao's pony incontinently rolled in the stream, and the rider was thrown into the water. He rolled over and over several times, but was at length dragged out, none the worse for his bath.

The journey from Hsin-lu-fang returning to Ko-pu was through lovely mountain scenery, but not without mishap. Evangelist Chin was riding a strange pony on a very narrow path along a precipitous hill-side, when his sun-hat caught in the branch of a tree, and his pony, taking fright, fell over the ledge, and, in falling, knocked over a Miao man carrying a basket. The poor fellow rolled down the hill-side about forty feet, and the pony and Chin rolled after him a little way. Fortunately no one was much injured, though it might easily have been otherwise. It is marvellous how ponies especially and men can roll down precipices and not be seriously hurt.

Most of the days, our way was sometimes along very narrow paths, winding round the slopes of steep hills, where no man with the least respect for himself would trust any legs but his own. My pony was a borrowed one, and had an unspeakably silly habit of stumbling on to his knees and nose several times a day without any sort of provocation. On such occasions I felt an almost irresistible impulse to go over his head, but I never entirely gave way to it! Mr. Adam also, who rode his own pony, and a much better one than mine, was constantly compelled to dismount. But it was amazing to see Mr. Tsao ride over some of the places. The sight of him often brought my heart into my throat, and kept it there, till he was safely over. I was not the only one who felt like that about it. My servant, a Heh Miao boy from Panghai, remarked after one of these dangerous feats of horsemanship, ''It is Mr. Tsao who rides the pony, and I who am afraid.'' Whether it was fearlessness or laziness that kept Mr. Tsao in the saddle, I do not know. There were some places, however, where even he had to dismount. There were also many steep hills up which no man with any moral sense could ride a pony, and no man with any common sense would venture to ride down. Consequently very much of our travelling had to be done on foot, dragging the ponies after us. As some of these stages were very long, I was sometimes so stiff and sore at night that I could not sleep.

Rickshaws in China

It was estimated that there were 100,000 rickshaws on the streets of Shanghai in the 1920s. The Communists outlawed rickshaws because they considered them degrading to those who drove them one, even though many rickshaw drivers thought it was perfectly reasonable way to make a living. Rickshaw drivers still eking out a living in Beijing often make most of their money by moving stuff for people who are too poor to hire a moving truck. One driver from Anhui Province who had no home in Beijing and either slept in his rickshaw or o a bench at the Forbidden City told the New York Times, “The only happy thing is to have money. You don’t have bitterness. You don’t have to feel tired.”

Most of the rickshaws left in Beijing are bicycle rickshaw, many of them with an electricified drive train. Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times in 2012: “China has blasted astronauts into space and is bringing bullet trains on line at a frantic pace, but the bicycle rickshaw endures. The roads in this city of 20 million people are choked with more than 5 million vehicles, and 20,000 are added monthly. That means the three-wheeled pedicabs are often at a competitive advantage, at least for short trips. Relatively unregulated and mostly unlicensed, the drivers duck and weave down side lanes and back streets, avoiding the clogged main thoroughfares. Their wanton disregard for lane markers, traffic rules and stoplights is hair-raising but expedient. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 7, 2012]

“These days, all but the poorest drivers have electrified their drive trains, creating e-bikes using car batteries stashed under the passenger seat. Your knuckles may be white, but the adrenaline takes your mind off all the exhaust you're inhaling.

“Outside the mall, I spotted a young bicycle rickshaw driver in a red jacket waiting for a passenger. Twenty yuan, he said, for the one-mile ride home, twice the $1.60 that a regular cab would charge. I didn't argue. I was lugging my laptop and a bunch of other stuff. This might have been his biggest fare of the day. A number of rickshaw drivers have told me they'll pocket 100 yuan daily, about $16. Regular taxi drivers may gross five times as much in fares over a 10-hour shift, but must pay for gas and the cab company commission; some say they're lucky to net $24.

“As the sky darkened and my rickshaw driver hurtled us around a bend on the wrong side of the road, I gave thanks he was there to pick me up. I might make it home before it began to pour. Even if he stopped at what I'd come to think of as "the force field."

One driver, a 42-year-old woman from Henan province named Liu, said there had been a crackdown on” rickshaw drivers in 2012. She said she's had four rickshaws confiscated since the spring. If you have connections, she said, you can pay $150 — a bribe or fine, it's not clear — to get your vehicle back. She said she had to dip into her savings for replacements, which cost at least $320 each. "You just have to find a way to keep going," she said, smiling. "What other choice do I have?"

Rickshaw Ambush and Seizure in Beijing

Makinen rickshaw ride came to an abrupt end with an assault. She wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Regular cabs always make the turn onto my lane and deposit me at my front gate, but I had found that rickshaw drivers avoid venturing beyond the corner. I'd gotten used to alighting at the intersection and walking the final few hundred feet. Not this day. The driver sped past the corner. Then suddenly, like a scene from a kung fu movie, the ambush began. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 7, 2012]

“Three men wearing black jackets and flailing batons set upon us with a vengeance. Shouting curses, one jammed his baton into the spokes of one of the back wheels. Another struck the driver on his back. The third began rifling through the basket on the front of the bike. I squawked and tumbled out of the back seat, aghast. The driver hopped off his perch. A crowd gathered.

“The assailants, I learned later, apparently were local toughs with some murky connection to the chengguan — lowly municipal officers, a rung below the police, with a reputation for thuggery. The duties of chengguan vary from district to district, but frequently they target unlicensed street vendors, levying fines and seizing property, or worse, meting out beatings.

“Apparently, my district's boundary begins at my corner, and no rickshaws are allowed. Maybe my driver was new in the big city, a rural migrant like most others in the rickshaw brigade, many poorly educated and lacking a Beijing residency card that might open other avenues of employment.

“In the chaos, I didn't have a chance to ask him such questions, let alone pay him my 20 yuan. The men commandeered his vehicle; there was no ticket written, no confiscated property report issued. This was summary justice, up close and ugly. And yet the driver quickly strode away with no protest, fixated on sending text messages from his phone. Who was on the receiving end? I wondered. And what would this misfortune mean to my rickshaw driver? Fortunately, we were not hurt. The next day, I went back to the U-town Mall, searching for him. Maybe I could at least find a friend of his, find out what happened, perhaps offer some help. He was nowhere to be found.

Transportation in the Mao Era

Discussing one way of defining social stratification in the Mao era in term of access to automobiles, Simon Leys wrote about “the riding classes and the walking classes”

For most of the period since 1949, however, transportation occupied a relatively low priority in China's national development. Inadequate transportation systems hindered the movement of coal from mine to user, the transportation of agricultural and light industrial products from rural to urban areas, and the delivery of imports and exports. As a result, the underdeveloped transportation system constrained the pace of economic development throughout the country. In the 1980s the updating of transportation systems was given priority, and improvements were made throughout the transportation sector. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

Ownership and control of the different elements of the transportation system varied according to their roles and their importance in the national economy. The railroads were owned by the state and controlled by the Ministry of Railways.

Transportation in China in the 1980s

“In 1986 China's transportation system consisted of longdistance hauling by railroads and inland waterways and mediumdistance and rural transportation by trucks and buses on national and provincial-level highways. Waterborne transportation dominated freight traffic in east, central, and southwest China, along the Chang Jiang (Yangtze River) and its tributaries, and in Guangdong Province and Guangxi-Zhuang Autonomous Region, served by the Zhu Jiang (Pearl River) system. All provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities, with the exception of Xizang Autonomous Region (Tibet), were linked by railroads. Many double-track lines, electrified lines, special lines, and bridges were added to the system. Subways were operating in Beijing and Tianjin, and construction was being planned in other large cities. National highways linked provincial-level capitals with Beijing and major ports. Roads were built between large, medium, and small towns as well as between towns and railroad connections. The maritime fleet made hundreds of port calls in virtually all parts of the world, but the inadequate port and harbor facilities at home still caused major problems. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

Civil aviation underwent tremendous development during the 1980s. Domestic and international air service was greatly increased. In 1985 the transportation system handled 2.7 billion tons of goods. Of this, the railroads handled 1.3 billion tons; highways handled 762 million tons; inland waterways handled 434 million tons; ocean shipping handled 65 million tons; and civil airlines handled 195,000 tons. The 1985 volume of passenger traffic was 428 billion passenger-kilometers. Of this, railroad traffic accounted for 241.6 billion passenger-kilometers; road traffic, for 157.3 billion passenger-kilometers; waterway traffic, for 17.4 billion passenger-kilometers; and air traffic, for 11.7 billion passenger-kilometers.

In 1986 a contract system for the management of railroad lines was introduced in China. Five-year contracts were signed between the ministry and individual railroad bureaus that were given responsibility for their profits and losses. The merchant fleet was operated by the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), a state-owned enterprise. The national airline was run by the General Administration of Civil Aviation of China (CAAC). Regional airlines were run by provinciallevel and municipal authorities. Highways and inland waterways were the responsibilities of the Ministry of Communications. Trucking and inland navigation were handled by government-operated transportation departments as well as by private enterprises.*

Three wheeler in Pingyao

Transportation was designated a top priority in the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1986-90). Under the plan, transportation-related projects accounted for 39 of 190 priority projects. Because most were long-term development projects, a large number were carried over from 1985, and only a few new ones were added. The plan called for an increase of approximately 30 percent in the volume of various kinds of cargo transportation by 1990 over 1985 levels. So each mode of transportation would have to increase its volume by approximately 5.4 percent annually during the 5-year period. The plan also called for updating passenger and freight transportation and improving railroad, waterways, and air transportation. To achieve these goals, the government planned to increase state and local investment as well as to use private funds.*

The Seventh Five-Year Plan gave top priority to increasing the capacity of existing rail lines and, in particular, to improving the coal transportation lines between Shanxi Province and other provincial-level units and ports and to boosting total transportation capacity to 230 million tons by 1990. Other targets were the construction of 3,600 kilometers of new rail lines, the double-tracking of 3,300 kilometers of existing lines, and the electrification of 4,000 kilometers of existing lines.*

Port construction also was listed as a priority project in the plan. The combined accommodation capacity of ports was to be increased by 200 million tons, as compared with 100 million tons under the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1981-85). Priority also was given to highway construction. China planned to build new highways and rebuild existing highways to a total length of 140,000 kilometers. At the end of the Seventh Five-Year Plan, the total length of highways was to be increased to 1 million kilometers from the existing 940,000 kilometers. Air passenger traffic was to be increased by an average of 14.5 percent annually over the 5-year period, and air transportation operations were to be decentralized. Existing airports were to be upgraded and new ones built.*

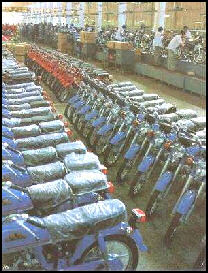

Motorcycles in China

Motorcycles and motorscooters are still the most practical and affordable vehicle for most people. China produced 11 million motorcycles and motorscooters in 2000, most of them for domestic use.

A popular vehicle among expats in Beijing is the Chang Jiang 750, often, called a CJ, with a side car. The vehicle is a late 1950s Chinese variation of a 1940s Russian Ural motorcycle which itself is a copy of the BMW R71, which debuted in 1938. A website described it as “Designed for Hitler, remodeled by Stalin and finally manufactured for Mao.”

Chongqing-based Lifan Motors is the largest maker of two-wheeled vehicles in China. It makes many of motorcycles sold in Vietnam, and sells products in 18 European countries.

Authorities are trying to curtail the use of motorcycles as way of reducing accidents, pollution and traffic. About 170 Chinese cites restrict motorcycles and some, including Shanghai, ban them. Guangzhou has banned motorized bicycles from the city center in an effort to reduce congestion.

Electric Motorbikes in China

Electric motorbikes are common sights in China and can sneak up on you in back alleys as they are much quieter than regular gasoline-powered motorbikes. Electric motorbikes should not be confused with e-bikes E-bikes are bicycles that still have pedals, and the electric motor is designed primarily to offer the user assistance, making the pedalling easier By contrast, electric motorbikes can be as powerful and fast as their petrol equivalents, and require the user to have a motorbike license. [Source: Erin Hale, BBC, June 27, 2022]

According to the BBC: China currently dominates global production of electric motorbikes, which are mostly scooters. One of the biggest producers is Beijing-based NIU Technologies, which launched its first models in 2015. Electric motorbikes previously existed in China, they used heavy, lead acid batteries. NIU was the first to sell electric motorcycles in the country with the same modern lithium batteries you find in a Tesla, or your mobile phone.Sales of electric motorbikes in China are being powered by government incentives and promotion as a means to help tackle urban pollution.

CFMoto 300 GT-E electric motorbikes are used by police in China. According to Electrek: The domestically made electric motorcycle falls in the 300–400cc equivalent class and is intended to give Chinese motorcycle cops a quick and reliable electric ride for largely urban patrols. CFMoto said the motorcycle has been “purpose-built to meet the demands of police departments across China’s mega cities,” and the specs seem to back up that claim. It’s not designed for ultrahigh speeds, but the 120 km/h (75 mph) should be plenty for urban patrols and the occasional pursuit. The bike sports a 16.8 kW peak-rated electric motor (22 hp), which isn’t rubber melting but should be able to pace most 300–400cc bikes and scooters thanks to the higher torque created by electric motors at startup. Few cities offer streets where speeds higher than this would be possible. [Source: Micah Toll, Electrek, June 19, 2022]

A fairly long range of 150 km (93 miles) should translate to effective urban patrols but also bumps up the portly weight of the bike to a staggering 224 kg (494 lb). Electric motorcycles with significantly longer ranges exist but are generally designed for both highway and city riding. The 300 GT-E, on the other hand, is designed for city use where 93 miles would be a relatively full day of riding.

Image Sources: 1) Columbia University; 2) BBC, Environmental News; 3, 7) University of Washington; 4, 5, 6) Nolls China website ; Julie Chao, Wiki Commons ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022