CHINA’S RAILWAY MINISTRY

Train and traffic going

to the Great Wall The Chinese rail system is controlled by the Ministry of Railways through a network of regional divisions, which often operate on austere budgets. China’s railway ministry employs 2.1 million people and has accumulated and retained its powers partly because of a traditional national-defense role. The Communist Party has relied on railways to speed troop movements since coming to power.

According to the New York Times: The Railway Ministry runs its own court system and is largely impervious to oversight. Zhang Kai, a lawyer who represented a passenger sentenced to three years in prison for slapping a train conductor, described the ministry as a “monster left over from the planned economy era” that resists reform or challenges to its authority. “It is common knowledge that the ministry is responsible for generating maximum profits while supervising itself,” Mr. Zhang said. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, August 28, 2012]

China’s Ministry of Railways runs the world’s largest rail network, employs more people than the U.S. government and has debts larger than Denmark’s economy. It both regulates and operates China’s trains. Hu Xingdou, an economics professor at the Beijing Institute of Technology, told Bloomberg, “The rail ministry has been run like an independent kingdom for years. The concentration of power has caused inefficiency and mismanagement, and it’s a hotbed for corruption.” The ministry uses a bidding process to award contracts for construction projects and buying new trains and equipment, according to the website of its engineering-project tendering unit. Still, it retains control of some parts-makers, said Yuan Gangming, a researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. [Source: Jasmine Wang, Bloomberg, August 4, 2011]

The ministry has been downsized previously as part of broader reforms, with hundreds of schools and hospitals it once controlled being handed over to local governments. China Railway Group Ltd. (601390) and China Railway Construction Corp., the world’s two biggest listed heavy-construction companies, were also once part of the ministry before being transferred to the state-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission. The nation’s two biggest trainmakers, CSR Corp. and China CNR Corp., were also previously under the rail department. They have since merged into the CRRC, the world largest train and rolling stock maker.

Articles on TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TRAINS IN CHINA: HISTORY, TRAIN LIFE, NEW LINES factsanddetails.com HIGH-SPEED TRAINS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS WITH CHINA'S HIGH-SPEED TRAINS: HIGH COSTS, SAFETY ISSUES AND CORRUPTION factsanddetails.com ; WENZHOU HIGH SPEED TRAIN CRASH IN 2011 factsanddetails.com ; FALLOUT OF THE WENZHOU HIGH-SPEED TRAIN CRASH factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's High-Speed Rail Development” by Martha Lawrence, Richard Bullock, et al. | Jun 30, 2019 Amazon.com; “Handbook on Transport and Urban Transformation in China” by Chia-Lin Chen, Haixiao Pan, et al. Amazon.com; “China's Great Train: Beijing's Drive West and the Campaign to Remake Tibet” by Abrahm Lustgarten Amazon.com; “Taking the Train to Tibet” by Chen Yang | Amazon.com; “Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train Through China” by Paul Theroux Amazon.com; “The Last Steam Railways: Volume 1: The People's Republic of China” by Robert D. Turner Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com; Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Liu Zhijun, Powerful Head of China’s Railway Ministry

China’s railway ministry was led by the former railway minister Liu Zhijun, who was jailed for corruption in February 2011. Liu was the head of China’s Railway Ministry at time when it was active getting China high-speed train program off the ground. Under Liu,David Bandurski wrote in the New York Times, a handful of government officials were entrusted with vast resources while being exempted from public scrutiny. China’s railroads were Liu’s private fiefdom, and he was rewarded politically for pushing ahead with big plans through unilateral decision-making, earning the nickname “Great Leap Liu.” [Source:David Bandurski, New York Times July 28, 2011]

Dominating resources of both power and money, Liu monopolized the debate among would-be experts. Dissenting voices, like that of Zhao Jian, a professor at the Economy Management Institute of Beijing Transportation University, were elbowed aside. In an interview published on the eve of the Wenzhou tragedy, Zhao told a magazine in southern China that his university president had discouraged him from criticizing high-speed rail development because it might hinder the school’s ability to secure research grants. Until the Wenzhou crash in July 2011, Chinese media were almost entirely complicit, trumpeting high-speed rail as a glorious enterprise reflecting the prestige of the Chinese Communist Party. No matter that the cost of tickets placed it out of reach for the vast majority of Chinese.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: Liu was a farmer’s son, small and thin, with bad eyesight and an overbite. He grew up in the villages outside the city of Wuhan, and left school as a teen-ager for a job walking the tracks with a hammer and a gauge. He had an innate sense of the path to power. Good penmanship was a rare skill in the provinces, and Liu perfected his hand, becoming a trusted letter writer for bosses with limited education. He married into a politically connected family and was a Party member by age twenty-one. He was a tireless promoter of the railways and of himself, and he ascended swiftly, heading provincial bureaus on his way to the seat of power in Beijing. By 2003, as Railroad Minister, he commanded a bureaucratic empire second in scale and independence only to the military, with its own police force, courts, and judges and with billions of dollars at his disposal. His ministry, a state-within-a-state, was known in China as tie laoda: Boss Rail. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 22, 2013]

China railway executive

riding with Russian President

Dmitry Medvedev “Liu kept his hair in an untidy black comb-over and wore a style of square horn-rimmed spectacles so common among senior apparatchiks that they are known as “leader glasses.” A colleague of Liu’s, a railway staffer who worked closely with him, told me, “Ever since the revolution, most Chinese officials look alike. They have the same face, the same uniform, even the same personality. They work step by step, and they are content to sit back and wait for promotions. But Liu Zhijun was different.” If it was possible to invest a railway job with glamour, he was determined to do so. He liked to convene meetings after midnight and make ostentatious displays of his work habits. Even as he approached the highest ranks of power, he never stopped flattering his superiors. When President Hu Jintao was returning by train to Beijing one summer, Liu hustled up the platform so frantically to greet him that he nearly ran out of his loafers. “I shouted to him, ‘Minister Liu, your shoes! Don’t fall!’ ” the staffer recalled. “But he couldn’t be bothered. He just kept grinning and running.”

“Liu’s success benefitted his brother Liu Zhixiang, who joined the ministry and soared up through the ranks. He was wisecracking and volatile—the Joe Pesci character of the family. In January, 2005, he was detained for questioning about embezzlement, bribe-taking, and intentional harm regarding his role in arranging the killing of a contractor who sought to expose him. By then, he was vice-chief of the Wuhan railway bureau. (The victim was stabbed to death with a switchblade in front of his wife. According to an official legal journal, he had predicted in his will: “If I am killed, it will have been at the hand of corrupt official Liu Zhixiang.”) The Minister’s brother had arranged for himself such a healthy piece of ticket sales that he accumulated the equivalent of fifty million dollars in cash, real estate, jewelry, and art. When investigators caught him, he was living among mountains of money so large and unruly that the bills had begun to molder. (Storing cash is one of the most vexing challenges confronting corrupt Chinese officials, because the largest bill in circulation is a hundred-yuan note, worth about fifteen dollars.) He was convicted and received a death sentence that was suspended and later reduced to sixteen years. But, instead of serving his time in a facility for serious offenders, he was transferred to a hospital where he reportedly continued to conduct railway business by phone.

“Back in Beijing, Minister Liu surrounded himself with loyal associates. The capo di tutti capi was the chief deputy engineer Zhang Shuguang, who once arrived at a railway conference in a fur coat and a white scarf and liked to describe his approach to negotiations as a “clasped fist.” For much of his career, he ran the passenger-car division, which gave him control over colossal spending choices. “It was all up to a nod of his head,” Zang Qiji, a retired member of the Academy of Railway Sciences, told me. Zhang had little experience with science, but he aspired to credibility and attempted to secure membership in an élite academic society by having two professors write a book in his name. (He fell short of membership by a single vote.

Great Leap Culture in China’s Railway System

Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times Work crews of as many as 100,000 people per line have built about half of the 10,000-mile network in just six years, in many cases ahead of schedule “including the Beijing-to-Shanghai line that opened a year early. Before the Wenzhou crash the entire system was on course to be completed by 2020. The costs are staggering. The general budget estimate for the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed railroad alone surpasses the entire budget for the Three Gorges Dam Project. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times June 22, 2011]

In December 2010, David Bandurski wrote in the New York Times, “the party’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper ran a front-page story valorizing an ordinary train driver who had been given a “dead order” from superiors back in 2008 to master a new high-speed train in just 10 days, against the judgment of a German trainer who said trainees needed at least two months. With all the high foolishness of state propaganda, the article relished the fact that the odds were stacked against the trainees and the fact that there was “no room for error.” [Source: David Bandurski, New York Times July 28, 2011]

The “great leap” culture that Liu Zhijun epitomized is the way things operate across China, from county towns bursting with development all the way up to the top. Party and government officials are accountable only to superiors with whom they hope to score expedient political points. The legitimate concerns of citizens are routinely ignored.

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Chinese people have pleaded with their leaders to slow down and prioritize the quality of development. “China, please slow your soaring steps forward,” one social media user wrote. “Wait for your people ... wait for your conscience! We don’t want derailed trains, or collapsing bridges, or roads that slide into pits. We don’t want our homes to become death traps. Move more slowly. Let every life have freedom and dignity.”

China’s leaders must recognize that the political culture of expediency and secrecy is the root cause of this and other tragedies, from food and mine safety to violent property demolition. Political reform is needed to empower Chinese citizens to monitor the government and eliminate corruption and mismanagement. Reform is the only way to enable real and sustained accountability.

In the face of mounting public anger, the government is now dealing more seriously with the crisis. Prime Minister Wen Jiabao has visited the crash site, pledging to hold those responsible to account, and the government has ordered an “urgent overhaul” of the national railway system. But this urgency must not, yet again, become mere expediency, another high-speed solution to a crisis of public opinion.

Questions about the rapid development of China’s high-speed rail network have simmered under the surface for years but were never given a proper hearing. "Liu had this great-leap mentality and he wanted to roll out this system much faster than they should have," Damien Ma, China analyst at Washington-based Eurasia Group, told the New York Times. "They did a lot of scrimping." Liu couldn’t be reached for comment. Wang says she hopes the government report on the accident will fix blame and prevent future accidents.

Impact of China’s New Rail Network

Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times, “Often overlooked, amid all the controversy, are the very real economic benefits that the world’s most advanced fast rail system is bringing to China “and the competitive challenges it poses for the United States and Europe. Just as building the interstate highway system a half-century ago made modern, national commerce more feasible in the United States, China’s ambitious rail rollout is helping integrate the economy of this sprawling, populous nation “though on a much faster construction timetable and at significantly higher travel speeds than anything envisioned by the Eisenhower administration. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times June 22, 2011]

For the United States and Europe, the implications go beyond marveling at the pace of Communist-style civil engineering. China’s manufacturing might and global export machine are likely to grow more powerful as 200-mile-an-hour trains link cities and provinces that were previously as much as 24 hours by road or rail from the entrepreneurial seacoast.

ridership numbers

Impact of China’s Rail Network on Freight

Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times, “The shift in passenger traffic to the new high-speed rail routes has freed up congested older rail lines for freight. That has allowed coal mines and shippers to switch to cheaper rail transport from costly trucks for heavy cargos. Because of this shift, plus the construction of additional freight lines, the tonnage hauled by China’s rail system increased in 2010 by an amount equaling the entire freight carried last year by the combined rail systems of Britain, France, Germany and Poland, according to the World Bank. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times June 22, 2011]

Among the biggest beneficiaries of the high-speed rail system are firms that contribute nothing to defray its costs. Those would be freight shippers, which now have more exclusive use of the older rail lines, with fewer delays. On the older tracks, the rail ministry has long been able to dictate that freight rates would subsidize passenger trains because the ministry owns those older tracks outright. The new, high-speed lines “passenger trains only “are owned by joint ventures between the rail ministry and provincial governments. That has prevented the ministry from forcing freight shippers to cross-subsidize the new high-speed services. As a result, passengers must pay much higher fares on the new trains than on the older ones.

The lack of freight subsidies is also causing concern in the rail and banking industries that the debt agreements of some joint ventures might need to be revised to extend the repayment of investment costs over more years.

Impact of China’s Rail Network on the Chinese Economy

Zhen Qinan, a founder of the stock exchange in coastal Shenzhen and the recently retired chief executive of ZK Energy, a wind turbine producer in Changsha, told the New York Times that high-speed trains were making it more convenient to base businesses here in Hunan Province. Populous Hunan has long provided labor to the factories of the east, but its mountains have tended to isolate it from the economic mainstream. Mr. Zhen ticked off Hunan’s attributes: “Land is much cheaper. Electricity is cheaper. Labor is cheaper.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times June 22, 2011]

Around China, Bradsher wrote “real estate prices and investment have surged in the more than 200 inland cities that have already been connected by high-speed rail in the last three years. Businesses are flocking to these cities, now just a few hours by bullet train from China’s busiest and most international metropolises.

Spring Festival travel mess

“The 820-mile Beijing-to-Shanghai line will create a business corridor between China’s two most dynamic cities and form a north-to-south artery with links to east-to-west rail lines at two dozen stations along the way. “It’s the network together that makes it work “knowing you can go from Shijiazhuang to Beijing and then transfer to Tianjin, so the coal guys can go to the port and conduct business with their shippers, for example,” said John Scales, a rail expert in the Beijing office of the World Bank who has advised China. “

Problems with the Rapid Growth of China’s Train System

China has one of the highest-density rail systems in the world, according to Michael Komesaroff of Urandaline Investments in Australia. He told Bloomberg "The Chinese are running at least two times the level of anyone else in the world. That means signaling and systems management become more critical.” [Source: Jasmine Wang, Bloomberg, August 4, 2011]

"I think since 2008 China has experienced what we call a 'great leap forward' of railway construction," said Ren Xianfang, a senior analyst at IHS Global in Beijing. "We've long had suspicions that this speed of construction is unsustainable."

The main problem, Ren said, are that the systems in place imply "there are lots of systemic fault lines with China's management of the high-speed train network" that has resulted in under-investment in the software infrastructure. "So even though we have very rapid build-out of physical infrastructure, the software management has not kept up.

Foreign capital investment in the freight sector was allowed beginning in 2003, and international public stock offerings are were offered in 2006. In another move to better capitalize and reform the railroad system, the Ministry of Railways established three public shareholder-owned companies in 2003: China Railways Container Transport Company, China Railway Special Cargo Service Company, and China Railways Parcel Express Company. [Source: Livia Bloom, Vice President, Icarus Films, film “Iron Ministry”, August 22, 2015]

New train in Tibet

China’s Railway Ministry Debt

China’s railway ministry held debts totaling 2.1 trillion yuan ($326 billion), or about 5 percent of gross domestic product, in 2011. It is China’s largest issuer of corporate debt. Even before the train crash in July 2011 it was finding it harder to raise funds for construction and other projects because of tightening credit and concerns about its borrowings. It was only able to find buyers for 18.7 billion yuan of one-year notes in a 20 billion-yuan sale on July 21. That was likely the first time the ministry had failed to reach a sales target, according to Guotai Junan Securities Co. [Source: Jasmine Wang, Bloomberg, August 4, 2011]

China spent $630 billion in 2012 on railway infrastructure, much of it for high-speed railways, down from $730 billion in 2011 and over $1 trillion in 2010. [Source: Elaine Kurtenbach, AP, March 12, 2012]

The railway ministry's massive debt liability requires annual interest payments of more than 120 billion yuan ($19 billion). Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times , “Financial regulators in Beijing have cautioned banks to monitor their rising exposure from hefty loans to the rail ministry. To pay for rapid deployment of the high-speed system, the ministry has borrowed more than $300 billion. It plans to invest an additional $115 billion this year, despite running losses on existing operations that it attributes mainly to rising diesel fuel costs for older lines, as well as rising interest payments. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times June 22, 2011]

Chinese Railway Corruption

In the early 2010s, Zhang Shuguang, deputy general engineer of the Ministry of Railway and director of its Transportation Department, was suspended on corruption charges . China's state auditor revealed that corruption derived from the Beijing-Shanghai line amounted to $17 million. Many believe that this figure wildly understates the problem. Zhang was an associate of Liu Zhijun, and a key player in the construction of China's high-speed railways. Wu Zhong wrote in the Asia Times, “ Details of the case are shocking the public. Zhang reportedly has US$2.8 billion stashed away in Swiss and US bank accounts, wealth rivaling that of a small country. This despite his status as a prefecture-level official, with a monthly salary of just 8,000 yuan (US$1,220). In terms of the money involved, Liu's case pales into insignificance in comparison with his protege - Chinese media estimate that Liu took up to 2.1 billion yuan in bribes. "The protege has outdone his master," as another Chinese proverb has it. [Source: Wu Zhong, Asia Times, March 8, 2011]

“In a typical case of a "naked official", Zhang had already moved his wife, child and presumably a large portion of his ill-gotten gains to the United States some time ago. The term "naked official", coined by Chinese netizens, describes an official who gradually shifts his family and wealth overseas so he can flee the country at any time...So how did Zhang - such a blatant "naked official" - remain in such a key post? How could he transfer such money out of the country without being discovered? How corrupt is the high-speed railway project, if Zhang took such a big bite off the cake? And rampant corruption is involved, has it affected the quality of high-speed railway projects?

“It is obvious that Zhang acted so recklessly because he had a "protective umbrella" - Liu Zhijun. Liu could have protected Zhang because he had virtually absolute, unchecked power in China's railway sector.When asked to comment on Liu's case, Premier Wen Jiabao said in an online chat with netizens on February 27 that it showed Beijing's determination to crack down on official corruption. However, he admitted that the abuse of power by the highest-ranking leader of a region or institution was possible because "our government and major officials have too much power. Power is too centralized without restriction."

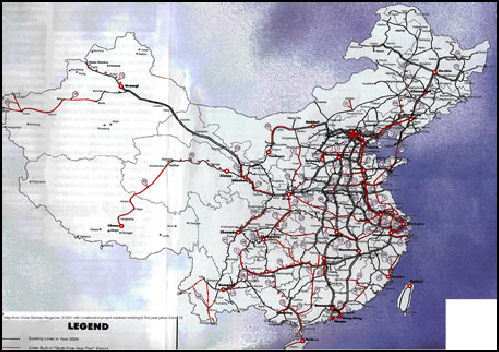

Train lines in China

Illiterate Egg Farmer Cashes in Chinese Railway Corruption

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: “ In August, 2010, the National Audit Office reviewed the books of a big state-owned company and came upon a sixteen-million-dollar “commission” to an intermediary in return for contracts on the high-speed rail. The intermediary turned out to be a woman named Ding Shumiao, who, perhaps more than anyone else, embodied the runaway riches created by China’s railway boom. Ding was an illiterate egg farmer in rural Shanxi—five feet ten, with broad shoulders and a foghorn of a voice. In the nineteen-eighties, after Deng Xiaoping launched the country toward the free market, she collected eggs from neighbors to sell in the county seat. That was illegal without a permit. The eggs were confiscated, and years later she still talked of her embarrassment. In time, she came to run a small, thriving restaurant, where she gave away food to powerful customers and exaggerated her own success. “If she has one yuan, she’ll say she has ten,” one of Ding’s longtime colleagues told me. “It makes her look more influential, and bit by bit people began to think that they could benefit from their friendship with her.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 22, 2013]

“Ding’s restaurant became a favorite with coal bosses and officials, and soon she was involved in coal trucking. Then she was “flipping carriages,” as it’s known in the railway business: working her connections to get cheap access to coveted freight routes and, according to Wang, the investigator, reselling the rights “for ten times what she paid.” She became friendly with Great Leap Liu around 2003, and, with her ties to the railway business, she prospered. Her company, Broad Union, signed joint ventures and supplied the ministry with train wheels, sound barriers, and more. In two years, Broad Union’s assets grew tenfold, to the equivalent of six hundred and eighty million dollars in 2010, according to China’s Xinhua news service.

“Ding’s given name, Shumiao, betrayed her rural roots, so she changed it to Yuxin, at the suggestion of her feng-shui adviser. She was easy to lampoon—Daft Mrs. Ding, people called her—but she had a genius for cultivating business relationships. A longtime colleague told me, “When I tried to teach her how to analyze the market, how to run the company, she said, ‘I don’t need to understand this.’ ” Caixin chronicled her audacious social ascent. To gain foreign contacts, she backed a club “for international diplomats,” which managed to attract a visit in 2010 by Britain’s former Prime Minister Tony Blair. Her lavish receptions drew members of the Politburo. She joined the lower house of the provincial legislature, and made so many charitable gifts that in 2010 she ranked No. 6 on the Forbes China list of philanthropists.

“Ding was detained in January, 2011, suspected of taking kickbacks totalling sixty-seven million dollars, according to the Global Times. (The ministry also accused her of working her connections to get Liu’s brother transferred from jail to a hospital.

Liu Zhijun Corruption and Mistresses

Railways Minister Liu Zhijun was dismissed in the spring of 2011 amid an investigation into unspecified corruption allegations. Initially no details were released about the allegations against him, but news reports say they include kickbacks, bribes, illegal contracts and sexual liaisons. After Liu's sacking, allegations quickly emerged that he had taken a 2.5 per cent cut on high-speed projects. In February 2011 there were reports that Liu accepted $122 million in kickbacks.

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: “In February, 2011, the Party finally moved on Liu Zhijun. According to Wang Mengshu, investigators concluded that Liu was preparing to use his illegal gains to bribe his way onto the Party Central Committee and, eventually, the Politburo. He told Ding Shumiao, ‘Set aside four hundred million for me. I’m going to need to spread some money around,’ ” Wang told me. Four hundred million yuan is about sixty-four million dollars. Liu actually managed to pull out nearly thirteen million, Wang said. “The central government was worried that if he really succeeded in giving out four hundred million in bribes he would essentially have bought a government position. That’s why he was arrested.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 22, 2013]

“Liu was expelled from the Party the following May, for “severe violations of discipline” and “primary leadership responsibilities for the serious corruption problem within the railway system.” An account in the state press alleged that Liu took a four-per-cent kickback on railway deals; another said he netted a hundred and fifty-two million dollars in bribes. He was the highest-ranking official to be arrested for corruption in five years. But it was Liu’s private life that caught people by surprise. The ministry accused him of “sexual misconduct,” and the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported that he had eighteen mistresses. His friend Ding was said to have helped him line up actresses from a television show in which she invested. Chinese officials are routinely discovered in multiple sins of the flesh, prompting President Hu Jintao to give a speech a few years ago warning comrades against the “many temptations of power, wealth, and beautiful women.” But the image of a gallivanting Great Leap Liu, and the sheer logistics of keeping eighteen mistresses, made him into a punch line. When I asked Liu’s colleague if the mistress story was true, he replied, “What is your definition of a mistress?”

“By the time Liu was deposed, at least eight other senior officials had been removed and placed under investigation, including Zhang, Liu’s bombastic aide. In the months that I spent talking to people about the rise and fall of Liu Zhijun, his story seemed to confound both his enemies and his friends. His rivals acknowledged that, unlike many corrupt officials, Liu had actually achieved something in office, and produced a railway system that will ultimately benefit the nation. And his defenders found themselves awkwardly saying that he was doing nothing that his peers were not. Liu’s colleague, an affable former military man, told me that at a certain point corruption became difficult for Liu to avoid: “Inside the system today, if you don’t take bribes you have to get out. There’s no way you can stay. If three of us are in one department, and you are the only one who doesn’t take a bribe, are the two of us ever going to feel safe?” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 22, 2013]

Liu was put on trial in 2013 and received a death sentence with reprieve in July 2013. In December 2015, Liu sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

Image Sources: 1) Nolls China website ; 2) Tales of Shanghai website; 3) Tibet Train com; 4) Stean train poster: Landsberger Posters < 5, 8) Seat 61 com; 6) Louis Perrochon; 7) China Trends; 9, 10) Xinhua; 11, 12) Gluckman com ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022