TRAINS IN CHINA

Railways: total: 150,000 kilometers (2021), second in the world, including 1.435-meter gauge (100,000 kilometers electrified); 104,0000 traditional, 40,000 high-speed. In August 2020, China announced plans to expand the country's railway network by one-third over the next 15 years.[Source: CIA World Factbook, 2022, Reuters]

Railways: total: 150,000 kilometers (2021), second in the world, including 1.435-meter gauge (100,000 kilometers electrified); 104,0000 traditional, 40,000 high-speed. In August 2020, China announced plans to expand the country's railway network by one-third over the next 15 years.[Source: CIA World Factbook, 2022, Reuters]

Trains form the backbone of the Chinese transportation system. They are the most popular means of long distance travel in China. They carry twice as much freight and passengers as Russian trains and three times as much as the U.S. trains. China's railways carried 1.36 billion passengers in 2007. The number of train passengers is growing by about 15 percent a year. In 2008, there were 1.46 billion journeys by rail, a 10.9 percent rise from 2007.

Railways are vital to the Chinese economy. China moves 54 percent of domestic trade by train, more than any other major country. Railroads in China carrying about 24 percent of the world’s railroad transportation volume. Around 2.5 billion tons of freight is carried every year and the rate is growing at a 11 percent rate a year. Most of the coal and oil is moved by train. Iron ore and coal are carried in by train to steel mills and the steel is transported out by train.

China's Railways Ministry controls every stage of train manufacturing, from design through to production and operation. This allows projects to progress faster than in other countries, and prices of train cars are about 20 percent cheaper than elsewhere. If China acquires the bullet train patents, its competitiveness in this market will further increase.

China's railroads are having a hard time keeping up with demands put on it by China’s growing economy (See Coal, Energy). China’s rail density is only 40 percent that of the United States and 11 percent that of Japan. China plans to spend to $205 billion on railroads and build 100,000 kilometers of new track between 2006 and 2010. Government plans call for spending 700 billion yuan ($106 billion) on railway building in 2011.

Rail lines in China, total: 68,141 kilometers in 2019 (compared to 322 kilometers miles in Guatemala and 28,241 kilometers in France).[Source: World bank worldbank.org ]

Articles on TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINA’S RAILWAY MINISTRY: ITS AMBITIOUS RAIL NETWORK, LIU ZHIJUN AND CORRUPTION factsanddetails.com ; HIGH-SPEED TRAINS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS WITH CHINA'S HIGH-SPEED TRAINS: HIGH COSTS, SAFETY ISSUES AND CORRUPTION factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN TRAIN: ITS ROUTE, CONSTRUCTION, IMPACT ON TIBET AND TOURISM factsanddetails.com; SHANGHAI SUBWAY COLLISION AND OTHER TRAIN ACCIDENTS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WENZHOU HIGH SPEED TRAIN CRASH IN 2011 factsanddetails.com ; FALLOUT OF THE WENZHOU HIGH-SPEED TRAIN CRASH factsanddetails.com ; MAGLEV TRAINS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Railways of China www.railwaysofchina.com ; Wikipedia article on Rail Travel in China Wikipedia ; Seat 61 Seat 61 ; China Train Ticket China Train Ticket ; Travel China Guide Travel Guide China Wikipedia article on the Shanghai maglev Wikipedia ; New Tibetan Train Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Tibet Train Travel tibettraintravel.com ; Links in this Website: NEW TIBETAN TRAIN Factsanddetails.com/China ; Book: “China’s Great Train” by Abraham Lustgarten (Times, 2008) is an interesting accounts of the building of China’s railroads.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Riding the Iron Rooster: By Train Through China” by Paul Theroux Amazon.com; “The Last Steam Railways: Volume 1: The People's Republic of China” by Robert D. Turner Amazon.com; “China's High-Speed Rail Development” by Martha Lawrence, Richard Bullock, et al. | Jun 30, 2019 Amazon.com; “Handbook on Transport and Urban Transformation in China” by Chia-Lin Chen, Haixiao Pan, et al. Amazon.com; “China's Great Train: Beijing's Drive West and the Campaign to Remake Tibet” by Abrahm Lustgarten Amazon.com; “Taking the Train to Tibet” by Chen Yang | Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com; Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Train History in China

First train in Shanghai in 1876 China's first railroad line was built in 1876. In the 73 years that followed, 22,000 kilometers of track were laid, but only half were operable in 1949. Between 1949 and 1985, more than 30,000 kilometers of lines were added to the existing network, mostly in the southwest or coastal areas where previous rail development had been concentrated. By 1984 China had 52,000 kilometers of operating track, 4,000 kilometers of which had been electrified

The first railway line built in China connected Shanghai with Woosung. Financed with foreign money and built with raw materials brought in from the hinterlands, the first five miles took ten years to build and the entire line was closed down a few years later after it opened in the 1860s after a riot broke out because a Chinese person was hit by a train. In 1878 the Chinese reopened the line and then dismantled it because the Qing rulers felt it scared the landscape, upset the laws of feng shui and provided easy access for invaders. The rulers purchased all the rails and equipment and had them thrown into the sea.

In 1896, China had only 370 miles of track, compared to 182,000 in the United States. After the end of the Sino-Japanese War in 1894, railroad construction began taking off in China. The Russians built a line across Manchuria, which was later expanded by the Japanese; the French built a line from Vietnam to Kumming; and the Chinese began building their own lines after the formation of the Chinese republic in 1916. It is ironic that Chinese labor helped to build the railroads in the United States while foreigners built most of the early railways in China. Foreigners taking over land to build rail lines was a major spark for the Boxer rebellion.

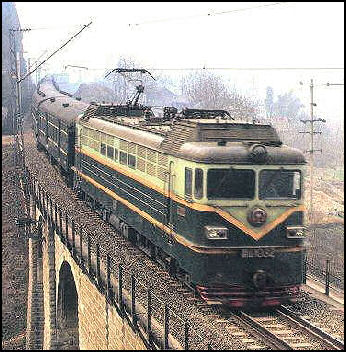

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: “Until now, China’s trains had always been a symbol of backwardness. More than a century ago, when the Empress Dowager was given a miniature engine to bear her about the Imperial City, she found the “fire cart” so insulting to the natural order that she banished it and insisted that her carriage continue to be dragged by eunuchs. Chairman Mao crisscrossed the countryside with tracks, partly for military use, but travel for ordinary people remained a misery of delayed, overcrowded trains nicknamed for the soot-stained color of the carriages: “green skins” were the slowest, “red skins” scarcely better. Even after Japan pioneered high-speed trains, in the nineteen-fifties, and Europe followed suit, China lagged behind, with what the state press bemoaned as two inches of track per person—“less than the length of a cigarette.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 22, 2013]

China’s Railways Under the Communists

Most of China's railways were built after the Communists came to power in 1949. Before 1935, China had approximately 20,000 kilometers of railways. When the Communists took over in 1949, only about half of these railways were running. Between 1949 and 1964, the Communists constructed 15,000 new kilometers of railways and added around 40,000 kilometers more in the 1970s, 80s and 90s.

Chinese railways increased in length from 21,989 kilometers (13,663 miles) in 1949, to 71,898 kilometers (44,721 miles) in 2002, of which 18,115 kilometers (11,267 miles) were electrified. In the rush to expand rail facilities during the "Great Leap Forward," the Chinese laid rails totaling 3,500 kilometers (2,175 miles) in 1958, with some 4,600 kilometers (2,900 miles) added in 1959. Many major projects had been completed by the 1970s, including double-tracking of major lines in the east; the electrification of lines in the west, including the 671 kilometers (417 miles) Baoji-Chengdu link; and the addition of several new trunk lines and spurs, many providing service to the country's more remote areas. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

While the total rail network is more than twice what it was in 1949, the movement of freight is more than 25 times that of 1949. Increased freight volumes have been achieved by loading freight cars up to 20 percent over their rated capacity and by containerization.

Railroads in China in the 1980s

In the 1980s all provinces, autonomous regions, and special municipalities, with the exception of Tibet, were linked by railroads. Many double-track lines, electrified lines, special lines, and bridges were added to the system. In 1985 the transportation system handled 2.7 billion tons of goods. Of this, the railroads handled 1.3 billion tons; The 1985 volume of passenger traffic was 428 billion passenger-kilometers. Of this, railroad traffic accounted for 241.6 billion passenger-kilometers. In 1986, railroads carried 1 billion passengers and 1.3 billion tons of cargo. The average freight traffic density was 15 million tons per route-kilometer, double that of the United States and three times that of India. Turnaround time between freight car loadings averaged less than four days. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987 *]

Ownership and control of the different elements of the transportation system varied according to their roles and their importance in the national economy. The railroads were owned by the state and controlled by the Ministry of Railways. In 1986 a contract system for the management of railroad lines was introduced in China. Five-year contracts were signed between the ministry and individual railroad bureaus that were given responsibility for their profits and losses.

Transportation was designated a top priority in the Seventh Five-Year Plan (1986-90). It gave top priority to increasing the capacity of existing rail lines and, in particular, to improving the coal transportation lines between Shanxi Province and other provincial-level units and ports and to boosting total transportation capacity to 230 million tons by 1990. Other targets were the construction of 3,600 kilometers of new rail lines, the double-tracking of 3,300 kilometers of existing lines, and the electrification of 4,000 kilometers of existing lines.*

Railroad technology also was upgraded to improve the performance of the existing rail network. There still were shortcomings, however. Most of the trunk lines were old, there was a general shortage of double-track lines, and Chinese officials admitted that antiquated management techniques still were being practiced. There were plans in the late 1980s to upgrade the rail system, particularly in east China, in the hope of improving performance.*

Between 1980 and 1985, China built about 3,270 kilometers of new track, converted 1,581 kilometers to double track, and electrified 2,500 kilometers of track. At that time railroads accounted for over two-thirds of the total ton-kilometers and over half the passenger-kilometers in China's transportation systems. China's longest electrified double-track railroad, running from Beijing to Datong, Shanxi Province, was opened for operation in 1984. One of the world's highest railroads, at 3,000 meters above sea level in Qinghai Province, also went into service in the same year, and improved doubletrack railroads, some of them electrified, offered a fast way to transport coal from Shanxi Province to the highly industrialized eastern part of the country and the port of Qinhuangdao for export.*

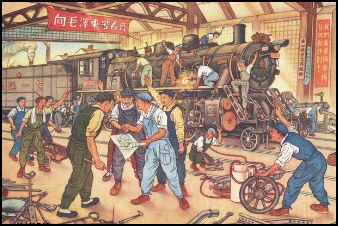

Production and maintenance of modern locomotives also made an important contribution to increased rail capacity. Manufacturing output in the mid-1980s increased significantly when production of electric and diesel locomotives for the first time exceeded that of steam-powered ones. China hoped, in the long-run, to phase out its steam-powered locomotives. In the mid-1980s China had more than 280,000 freight cars and about 20,000 passenger cars. The country still was unable, however, to meet the transportation needs brought about by rapid economic expansion.*

Railroads in China in the 2000s

China had 74,438 kilometers, or 46,235 miles of train track in 2005, compared to 486 miles in Ethiopia and 21,160 miles in France. Of this 20,151 kilometers was electrified. At that time China was the world’s most prolific railway builder. It added between 6,000 kilometers of track a year. As of 2005, 82 percent of China’s railroads were controlled by the central government. The remainder were under the control of local governments. The Chinese train system employed 212,000 people in the 2000s.

In 1991, China invested $8 billion for infrastructure improvements, including the upgrade of 309 kilometers (192 miles) of double-track railway and the electrification of 849 kilometers (528 miles) of track. In 2005, foreign investors were invited to invest in Chinese railroads for the first time — on six local rail lines in the northern province of Shandong. Nationwide, shortages of freight and tank cars delayed deliveries of coal and other industrial raw materials to their destinations. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies: in the 2000s, every province-level administrative unit except Tibet was served by rail, and plans were being made to extend a line south from the Lanzhou-Urumqi line to Lhasa in Tibet. More than 50 percent of the country's traffic is moved by the railroad system. China's railway network consists of a series of north-south trunk lines, crossed by a few major east-west lines. Most of the large cities are served by these trunk lines, forming a nationwide network, with Beijing as its hub. [Source: Robert Guang Tian and Camilla Hong Wang, Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies, Gale Group Inc., 2002]

In 2004 China’s railroad inventory included 15,456 locomotives owned by the national railroad system. The inventory in recent times included some 100 steam locomotives, but the last such locomotive, built in 1999, is now in service as a tourist attraction while the others have been retired from commercial service. The remaining locomotives are either diesel- or electric- powered. Another 352 locomotives are owned by local railroads and 604 operated by joint-venture railroads. National railroad freight cars numbered 520,101 and passenger coaches 39,766. [Source: Livia Bloom, Vice President, Icarus Films, film “Iron Ministry”, August 22, 2015]

Train Lines in China

There are two main trunk lines. One runs south to north along the east coast between Guangzhou, Beijing and Harbin. The other runs from east to west between Beijing, Zhengzhou, Lanzhou and Urumqi. The three-day journey from Beijing to Urumqi is on the "Iron Rooster," a train immortalized by writer Paul Theroux in book by the same name. This line has now been extended to Kashgar. The railway between Chengdu and Kunming goes through 427 tunnels and crosses 653 bridges as it twists through mountainous Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. The new train in Tibet was achieved with even more impressive engineering feats.

Poster for steam train factory Two of the three main Trans-Siberian routes travel through China to Beijing : 1) the 5½-day, 7,865-kilometer "Trans-Mongolian" route from Moscow to Beijing route which breaks off from the main line past Irktusk and Lake Baikal and passes through Ulan Batar, Mongolia and the Gobi Desert; and 2) the 6½-day, 9001-kilometer "Trans Manchurian" Route, which breaks off the main line at Tarskaya and travels to Beijing via Harbin in Manchuria

The route through Mongolia is the most popular route. People prefer passing through Mongolia, which is more exotic than going through Manchuria. The main problem with these route is that you have to endure long waits, around 12 or so, at the Chinese-Mongolia border and the Mongolian-Russian border.

New Railroad Lines in China

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was drive to build railroads in remote parts of China to unite the country, help the poor, help poorer regions of the country, and help the government exert stronger control and better exploit resources. The government had plans to lay 13,600 kilometers of track nationwide between 2000 and 2005 at a cost of $45 billion. The construction was aimed particularly at narrowing the economic gap between the rich coastal areas and the poorer interior of country by making it easier to move goods to and from the interior. It was also aimed at clearing bottlenecks that hindered economic growth.

Rail construction has forged ahead an astonishing rate; 2,500 miles of new track a year, the Communications Ministry says, along with upgrades on existing rail lines to improve trains’ speed and carrying capacity. China is building high speed railroads and expanding freight lines and hooking up railways to its equally ambition subway building programs. In October 2008, the Chinese government approved $100 billion for trains as part of its stimulosus program to get the Chinese economy going.

China needs new railroads to maintain its economic growth. As of 2005, railways met only 35 percent of the demand for commodities such as coal and industrial goods. At that time there were plans to build seven new passenger lines, 25,000 kilometers of new track at a cost of $250 billion before 2020. China is hoping that foreign investors will foot some of the bill. The new 1,575 mile railway between Beijing and Hong Kong, completed in 1997, cost $4.8 billion and employed more than 210,000 workers to build. It was the most ambitious infrastructure project in China after the Three Gorges Dam.

China is building new tracks and linking them with old track to complete a 1,400 railway route between Russia and the Chinese port of Dalian that parallels the North Korean border The rail line will provide access from the Trans Siberian to the ice-free seas off China, by bypass North Korea and provide North Korea with important links to the outside world. The Yunnan provincial government is spending $6.4 billion to develop a railroad network that will connect China with Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar that is expected to be operational in 2010. China has offered to pay $4 billion to finance a railway between Kunming and Bangkok..

China is planning three transnational routes and is negotiating with 17 countries to set up trans-continental routes to Singapore, Germany and London. One of its primarily aim is to ship freight overland to Asia, the Middle East and Europe and not be so dependent on ship to transport Chinese-made goods. The London route is expected to be up and going by 2025.

See Separate Articles: HIGH-SPEED TRAINS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN TRAIN: ITS ROUTE, CONSTRUCTION, IMPACT ON TIBET AND TOURISM factsanddetails.com

Bogey Changes and Steam Engines in China

At the Chinese-Russian border and the Chinese-Mongolian border, the bogies (the undercarriages and wheels of the train cars) are changed to accommodate the train tracks in Russia and Mongolia, which are 10 centimeters wider than the tracks in China and Europe..

The bogey changing is quite interesting. Inside a large shed near the station — with all the passengers still in the train — the carriages are separated and lifted by hydraulic jacks. Work crews of men and women with bolt guns detach the bogies, which are then collectively pushed from underneath the carriages and new bogies with a wider sets wheels are pushed in and attached by the crews.

Why are the Russian gauges wider than other train gauges? According to one story, the wide gauging was designed to thwart military invasions (the idea being that narrow-gauge trains carrying troops and weapons into Russia would be stopped cold at the border). The wide tracks did slow down the Nazi advance in World War II but they were originally chosen over narrow gauges because they are considered safer.

China continued using steam engines — which are not all that different from engines used in the 19th century — until fairly recently. The Datong Locomotive Works was the last factory in the world that made them. What was particularly surprising about the factory is that nothing was automated.

Paul Theroux wrote: “Everything is handmade, hammered out of iron, from the huge boilers to the little brass whistles...It is essentially just a complex of sheds, but one that covers a square mile. Men squat in fireboxes, hunched over blow torches; they crawl in and out of boilers, slam bolts with hammers, drag axles and maneuver giant wheels overhead using pulleys...donkey carts carried heavy iron fittings through the factory, the donkey's sniffing the fires of the forges and looking miserable but resigned.”

The last steam factory was closed in 1989. The first diesels were imported from France and Romania but now China makes its own.

China’s Slow Trains

According to an article in the China Daily: “There was a gray dawn light and soldiers were clearing snow at Qijiabao station when "Old Liu" and his wife boarded the slow train to Dandong in frozen Liaoning province. They were dressed warmly, took their places in the hard-seating section, faced each other across a table and silently watched the scenery drift by. The retired food factory workers, both 66, rarely travel but Liu needed to see the dentist. He opened his mouth and pulled on his upper lip to expose sepia-colored teeth and a gap where the incisor should have been. It had broken off and the stump was still visible. [Source: China Daily, December 22, 2008]

“Slow trains like the 2251 from Beijing to Dandong are a lifeline for people like Liu. He said there's no dentist in Qijiabao, a small town in Liaoning, nor buses, and he never learned to drive a car. The train is cheap and convenient. His wife nodded in agreement all the while, smiling but mute. Thousands of people depend daily on this slow train and others like it, but it's part of a vanishing network as a new round of rail modernizations replaces them.

“It was as if we were journeying into the past when our diesel-powered train puffed out of Beijing Railway Station at 12:20 pm on a recent weekday, packed with migrant workers, flush with cash and alcohol. The 23-year-old locomotive rattled along at just 60-80 km/h. When the tracks ran parallel to the road, cars zipped by and even buses steadily pulled away from us.

“The journey would take 21 hours 22 minutes, stop at 21 stations and cover 1,166 kilometers. All for the bargain price of 147 yuan ($21). On the 16 carriages, including a mail van, there appeared to be six classes of temporary accommodations. At the bottom end was standing. Young farmer, Po Ting, said he was returning to Liaoning after visiting Beijing for the first time. He leaned against the wall in one of the gangways between the carriages, playing Taoist mantras on his mobile phone at maximum distortion. Others sat glumly on their bundles near the doors.

Life on China's Trains

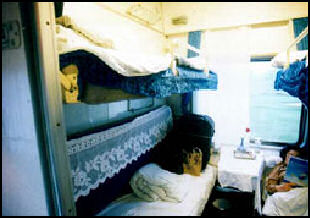

Soft sleeper

Chinese trains are a good introduction to Chinese life. Loudspeakers broadcast staticky news reports from the Peoples Daily and sentimental songs up to 18 hours a day. In their seats, passengers do their washing, party to loud music from cassette players, play cards and mah-jong, and lounge around in their underwear or pajamas, putting on coats when they go to the meal car. In the aisles, they spit, eat noodles, and do tai chi. It is not unusual for a passenger on train to share a four person compartment with a 78-year-old women and a honeymooning couple doing what newlyweds usually do on their first night together in the upper bunk.

At some train stations, hundreds of passengers line up on the platform before boarding. Ten minutes before the train leaves a guard blows a whistle, and the passengers dash to the train, with women and children usually getting the worst seats.

Guangzhou Railway station is arguably the world’s busiest, during the Chinese New Year when millions of migrant workers that work in the Guangzhou-Shenzhen area head home to their villages.

Train Classes in China

There are four kinds of classes available on Chinese trains: hard seats, soft seats, hard sleepers and soft sleepers. Traveling on a hard seat train is the equivalent of traveling 3rd class in a third world country. Hard seats are hard and uncomfortable and the carriages are often crowded with Chinese peasants with large bags and bundles. Soft seats are comfortable seats in less crowded carriages. They are fine for daytime journeys.

Hard sleepers are bunks in open compartments, with six bunks to a compartment, three on each side. The top bunk is about six feet off the ground, which means there is a lot of space between the bunks. Hard sleepers usually cost twice as much as hard seats. Hard sleeper carriages are often crowded, smokey, noisy and uncomfortable.

Soft sleepers are closed bunk compartments for four people. The beds are generally reasonably comfortable and each bunk has a reading light and clean sheets. Try to get a lower bunk, which is more comfortable to sit in when you are not sleeping. Soft sleepers generally cost twice as much as hard sleepers. The compartments are shared by strangers or both sexes.

Because soft sleepers are considerably more expensive than other classes it is usually not very difficult to get a seat. Some have air conditioning, some don't. The toilets are generally pretty clean and hot water is served for tea. The main drawback is that a lot of people smoke.

Life China’s Slow Trains

Hard sleeper

A Chinese writer wrote in the China Daily: “I've been told a couple of times the best way to experience China is to take a slow train to some far-off destination. Instead of the countryside flashing by there's time to watch it unfold and you have little choice but to serendipitously befriend people you wouldn't normally meet. It's true.

“Hard-seating class was like a club — loud, lively and smoky. Extended families made the most of their confinement by snacking, drinking and socializing. Soft seating was much the same, but the air was fresher and there were fewer people. I was in hard sleeper with six bunks in a space little larger than two office cubicles. At the top there wasn't enough headroom to sit up straight, so I unpacked semi-reclining. Otherwise, it was relatively comfortable. Actually, the beds are not that hard and the bedding was clean.

“A family dressed in matching black leather coats boarded in Fuxin and arranged themselves on the seats outside our hard sleeper compartment. They struck up a conversation with a solicitor called Gong Guanchi, from Chaoyang, who had got on three hours previously. “He has a practice in Dandong and works there six days a week, returning home for three days off. I said it seemed like a long commute (610 km) but he shrugged his shoulders. Taking this train allows him to arrive early enough to work a whole day in the office. He appeared to have no trouble sleeping in a sitting position.

“I was sharing with a married couple and their 15-month-old kid, who thankfully turned out to be one of the quietest people on the train. Another couple bunked below me and it wasn't until about 9 pm that a teenager climbed into the empty bed opposite. Before long he was sobbing and when I looked over he was cradling his mobile phone, with his back to me, telling the girl on the other end not to cry. The tragedy continued. His message alert was a machine gun sound and throughout the long night there was continuous fire. Love is, sometimes, a battle.

“Soft sleeper was more spacious, with a door and just four bunks to a room. At the top of the train was a carriage from which I was barred, but I nevertheless returned a little later for a sneak peak. A small group of men had the car to themselves and were toasting each other. A guard later told me they were "lingdao", top officials or businessmen.

A pair of lovers whiled away their journey in the dining car, shared a bottle of water, stroked each other's hair and took turns to sleep. Toward the end of the journey staff and vendors congregated out of uniform in the diner to chat and count the money they had made by selling sunflower seeds, packed meals and xuegao ice-lollies.

“As the light outside faded to black, the music in our compartment changed from patriotic songs, to pop ballads and finally ambient/religious music, before the strip lights were extinguished at 9:30 pm. They came back on at 6:30 am. At 3 am, however, I needed the bathroom and felt it was my duty to scout around. The toilets were steel-rimmed holes and it was forbidden to use them at stations. They were simple but serviceable and showed signs of being cleaned. Hard and soft seating had emptied a bit and some passengers spread their lengths across the seats. We arrived on time in Dandong at 9:42 am.

Scalpers, Trains and Chinese New Year

China’s 5,700 train stations are the home of “yellow bulls”’scalpers who buy tickets at list price and then resell them at a higher price. They are particularly active during the Chinese New Year, when hundreds of millions of tickets are sold and seats are in short supply and the scalpers can demand high prices. Top scalpers can earn up to $360 a day, a healthy chunk of money in China.

Over the Chinese New Year holiday a scalper can sell $50 tickets for around $100. They say they have no problem finding customers. The only thing that limits their profits is an inability to get enough tickets to meet demand. By one estimate 10,000 yellow bulls operate at the two main trains stations in Beijing alone. Many are pregnant women, who according to Chinese law, are exempt from arrest or fines.

See Last Train Home Under RECOMMENDED AND ACCLAIMED CHINESE INDEPENDENT DOCUMENTARY FILMS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEW YEAR FIXTURES: LONG TRIPS HOME, MIGRANT WORKERS factsanddetails.com;

Image Sources: 1) Nolls China website ; 2) Tales of Shanghai website; 3) Tibet Train com; 4) Stean train poster: Landsberger Posters < 5, 8) Seat 61 com; 6) Louis Perrochon; 7) China Trends; 9, 10) Xinhua; 11, 12) Gluckman com ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022