RECOMMENDED CHINESE INDEPENDENT DOCUMENTARY FILMS

Super, Girls “Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers” (Liulang Beijing) directed by Wu Wenguang (1990) is regarded as the first independent Chinese documentary. La Frances Hui of the Asia Society wrote: Considered the godfather of independent Chinese documentary filmmaking, Wu Wenguang documents the life of struggling young artists in Beijing. This film provides insights into how contemporary Chinese artists whose works now fetch millions at international auction houses might have begun their careers. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Yu Guangyi’s "Changbaishan Sanbuqu" (White Mountain Trilogy) is comprised of “Timber Gang” (2004), “Survival Song” (2007"), and Bachelor Mountain” (2010). Timber Gang” is a documentary that confronts the viewer with a China not-yet eclipsed by massive development, depicting the grueling, Herzogian conditions of rural subsistence labor. Lumberjacks in a mountainous area of China use a method that has not changed for centuries. The men stay in humble cabins, where they eat, drink wine and sleep together. This is the last year for the lumberjacks. In the spring they will start looking for other work in the city.

Translator Cindy Carter told Bruce Humes of Ethnic China You can’t talk about the current state of Chinese manhood without referencing Yu Guangyi’s "Changbaishan Sanbuqu" (White Mountain Trilogy), about the inhabitants of the remote national forests of north-eastern China. It’s not all about the menfolk, of course, but in these northern climes, where women are a scarce commodity, the gender-gap colours every aspect of society. I translated the last two films of the trilogy, and we’re still looking for an investor for finance the retranslation and subtitling of the first part (Timber Gang). [Source: Bruce Humes, Ethnic China, May 14, 2012]

“Wind, Flowers, Snow, Moon” (2008), directed by Yang Jianjun, is set in small village in the northwest of Sichuan province, where Mr. Yang, a ninety year-old grandfather, is the ninth-generation successor in a family of fengshui experts. They preside over funerals for the village. The documentary focuses on intimacy with life-and-death and the tragedy of how “the young perish, while the old linger”. Sons and daughters wrangle over funeral expenses; an affectionate couple dies, one after another. Yang’s family celebrates the birth of his great-grandchildren while simultaneously burying a son who has died of cancer. Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films wrote: “”Wind, Flower, Snow, Moon” is one of the most quietly beautiful documentaries of recent memory. With a gifted eye, first time director Yang painstakingly details life among his own family, who practice the ancient art of Buddhist geomancy, bringing blessings to others at all stages of life in northwest Sichuan province. To be honest, it’s not so much a ground-breaker as an exceptional film whose unassuming manner of mastery is at risk of being lost in the shuffle. It’s criminal that this film wasn’t pushed or noticed more in the fest circuit. But it just goes to show that there is no end to the discoveries to be found in Chinese independent cinema.” [Source: Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

See Separate Articles: SIXTH GENERATION FILMMAKERS AND ACCLAIMED ART HOUSE MOVIES FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; JIA ZHANGKE factsanddetails.com ; INDEPENDENT FILM MOVEMENT AND DOCUMENTARY FILMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ZHAO LIANG, HU JIE AND WANG BING: MASTERS OF CHINESE INDEPENDENT FILM factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record” by Chris Berry, Xinyu Lu, et al Amazon.com; "Independent Chinese Documentary — From the Studio to the Street" by Luke Robinson Amazon.com; “DV-Made China: Digital Subjects and Social Transformations after Independent Film” by Zhen Zhang, Angela Zito, et al. Amazon.com; “Postsocialist Conditions: Ideas and History in China’s “Independent Cinema, 1988-2008" by Xiaoping Wang Amazon.com; “Memory, Subjectivity and Independent Chinese Cinema” by Qi Wang Amazon.com; “Independent Chinese Documentary: Alternative Visions, Alternative Publics” by Dan Edwards Amazon.com; “From Underground to Independent: Alternative Film Culture in Contemporary China” edited by Paul G. Pickowicz and Zhang Yingjin Amazon.com; “Filming the Everyday: Independent Documentaries in Twenty-First-Century China” by Paul G. Pickowicz and Yingjin Zhang | Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com;

Films by Wu Wenguang: the Godfather of Chinese Independent Cinema

Wu Wenguang is considered by many to be the godfather of Chinese independent cinema. Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: He plays the role with gusto: Gruff and gregarious, he wears John Lennon glasses, blue jeans and a T-shirt that reads "100 percent life, 0 percent art" above a crude sketch of a video camera. “Wu moved to Beijing in 1988, abandoning his hometown in southwestern China's Yunnan province for a job at CCTV, China's state broadcaster, but quickly became disillusioned by the station's propagandistic bent and gravitated toward the fringes of society. He read Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He fell in with a few young artists, writers and photographers trying to eke out a living in the nation's capital; using a Betacam borrowed from the CCTV studio, he began to film their lives. Two years later, in 1990, the footage became his first film, a searing, stripped-down documentary called "Bumming in Beijing. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, October 14,2105]

“Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers” (Liulang Beijing), directed by Wu Wenguang in 1990, is regarded as the first independent Chinese film. La Frances Hui of the Asia Society wrote: Wu Wenguang documents the life of struggling young artists in Beijing. This film provides insights into how contemporary Chinese artists whose works now fetch millions at international auction houses might have begun their careers.

Chris Berry wrote: Everything is hand-held camera, muddy sound, stumbling interviews that are clearly not rehearsed, and so on. The most notorious “on the spot” moment in the film is when Wu accidentally comes across his friend, a painter, having a psychotic episode. Imagine that for 30 years, you have seen only glossy films about bumper harvests and the achievements of socialism. Then you see this. So, as you can imagine this was quite shocking for viewers in the 1990s. [Source: Chris Berry, professor at Kings College, London, dGenerate Films, November 14, 2013]

“Fuck Cinema” (Cao Tamade Dianying) )2005) is another Wu Wenguang film.Yingjin Zhang, a Professor of Chinese Literature at University of California, San Diego, wrote: Wu Wenguang follows an impoverished migrant worker who is desperately pitching his amateur screenplay in Beijing. Wu sometimes places himself in front of the camera and is relentless in depicting the film world as more deceiving than alluring. His critical self-reflexivity establishes the film as both documentation and performance, thereby encouraging the view to explore a new ethics of the self vis-à-vis the other.

Wu Wenguang is the driving force behind the “Memory Project” — a grass-roots effort to build a historical archive of firsthand stories some of the darkest periods of the Chinese Communist Party's rule. Kaiman wrote: “Since 2010, the project's 200 or so volunteers have filmed more than 1,300 interviews with elderly villagers across the country, seeking to record their voices before they die. The project's interviews are raw and personal, captured on front porches and in living rooms and kitchens, full of lengthy digressions and background noise.[Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, October 14,2105]

“The Chinese government would prefer that such stories be forgotten.Wu Wenguang won't let that happen. Wu calls it the Memory Project: a grass-roots effort to build a historical archive of firsthand stories from the darkest — and, because of pervasive censorship, least-understood — periods of the Chinese Communist Party's rule. Since 2010, the project's 200 or so volunteers have filmed more than 1,300 interviews with elderly villagers across the country, seeking to record their voices before they die. The project's interviews are raw and personal, captured on front porches and in living rooms and kitchens, full of lengthy digressions and background noise. When asked whether he's afraid of official harassment, Wu shrugs. "In a country where the red line always exists, you just need to seek out what you can do," he says. "This is a very personal way of working."

Films About the Impact of the Three Gorges Dam

“ “Bing Ai” (Bing Ai) directed by Feng Yan (2007): Feng Yan spent seven years in the Three Gorges region following a peasant woman, Bingai, who refused to give up her land for new development. Zhang Xianmin, a film producer and festival organizer, wrote: Feng is greatly moved by Bingai’s uncompromising personality. Feng says that most Chinese people give up their land too easily, like losers. Meanwhile, the extraordinary effort Feng puts into making this documentary is comparable to Bingai’s perseverance. In this sense, the filmmaker and her subject are mirror image of each other.

“Before the Flood” (Yan Mo) directed by Yan Yu (2005) is a landmark documentary following the residents of the historic city of Fengjie as they clash with officials forcing them to evacuate their homes to make way for the world’s largest dam. Shot over two years, Before the Flood is a breathtaking achievement in verité-style documentary filmmaking. This profound film shows the human effects of one of history’s grandest social engineering projects, reflecting on the loss of both home and heritage. Translator Cindy Carter told Bruce Humes of Ethnic China A sprawling documentary about the demolition and relocation of an ancient village in the path of the Three Gorges Dam Project, "Before the Flood" touches on a number of issues (property rights, community, local politics, religious revival in China, etc.) that would inform the work of these directors for years to come. [Source: Bruce Humes, Ethnic China, May 14, 2012]

Famed Chinese indepedent filmmaker Jia Zhangke wrote: The Three Gorges Project is about to bury the thousand-year-old ancient city of Fengjie in rising water. With their cameras in hand, the directors linger on the old town of Fengjie, in the process of being demolished. Anticipating the monumental changes, people here are trapped in a web of complex conflicts. With the city submerged, will the memory of it endure? [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Yung Chang’s “Up the Yangtze” is highly-acclaimed film in the vein of Jia Zhangke. It is about the mass displacements caused by the building of the Three Gorges Dam and the widening gap between cities and the countryside. “Up the Yangtze” won the Golden Gate Award for Investigative Documentary Feature at the 2008 San Francisco International Film Festival.

Films by Xu Tong

Xu Tong's Shattered “Wheat Harvest” directed by Xu Tong (2008) is a film about prostitution in China. The discussion after the screening centered on the fact that the filmmaker didn’t obtain proper consent from the sex workers he had filmed. Since sex work is illegal in China, the film might have brought risk of arrest and prosecution to the subjects in the film.

Chris Berry of Kings College, London wrote: Xu Tong made “Wheat Harvest” hanging out with a very young sex worker and trying to understand her life. Let me say right now that although I’m sure a lot of things were handled badly, I don’t think this is an exploitative film. But when it screened in Hong Kong, there were accusations that, because he didn’t disguise her identity or where she worked, he was making her vulnerable to vigilante violence. Then, at a later date, the sex workers in the film claimed they had not adequately understood what was going on, and demanded financial compensation.

“Fortune Teller” (2010), directed by Xu Tong, is about a pimp named Li Baicheng who makes a living by telling the fortunes of prostitutes and others in the demimonde of salons and massage parlors. In his forties, he met Pearl Shi, a woman cruelly mistreated at home because of her disability. He decided to leave their hometown, taking her with him to the countryside of northern China. But now a bitterly cold winter combines with a campaign against prostitution to send the couple back to their hometown. Spring is coming; they take to the road once more and travel to a fair where they wait for their luck to turn. A fascinating look at how people still find meaning in old traditions of divination in their fast-paced urban lives.

Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films wrote “Fortune Teller” continues the detailed portraiture of the professional underclass heexhibited in his first documentary Wheat Harvest, expanding it into a 360 degree panorama of a vibrant, sprawling subculture that could never be shown in mainstream Chinese media. Xu ironically employs the chaptering structure of classic Chinese novels to tell the story of a crippled soothsayer, his mentally disabled wife, and a clientele of prostitutes ever anxious about their futures. Xu doesn’t do this to elevate his socially disreputable subjects, but to collapse notions of high and low into a universally moving story of people who bring uncommon dignity to their lives and work. [Source: Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

Films by Zhao Hao

Zhou Hao won the Best Documentary Award at the Golden Horse Awards in Taiwan for two years in a row for “Cotton” (2014), a documentary centered on the life of workers and farmers in the cotton industry; and “Datong” (2015), named after a city the northern part of Shanxi Province and focusing on the city’s major famous for ordering massive demolitions. According to the Global Times: “Once a photographer with the Xinhua News Agency and later Southern Weekly, Zhou possesses an experienced sense of what should and should not be recorded under his lens. “Houjie" was Zhou's first documentary. Made in 2001 while he was still a photographer at the Southern Weekly, it takes aim at a group of people living in Dongguan, a city once famous as a major Chinese manufacturing base and infamous for its covert sex trade. "Senior Year" is a documentary recording the life of a class of senior high school students about to take the national college entrance exam. It won the Hong Kong International Film Festival Humanitarian Award (Documentary) in 2006.“His "single-person" series has also gained quite a lot of attention as independent films. "Long Ge" (2008) focused on drug dealers and users, while "The Transition Period" (2009) explored the life of a CPC secretary belonging to a local county committee. Both films uncover various representative or unnoticed phenomenon in Chinese society. [Source: Global Times, December 20, 2015]

In regard to "Datong", Datong is important as it boasts the highest concentration of coal in the country, generates electricity for many parts of North China and once played a significant role in the economy during a time when China relied heavily on extensive growth. However, going hand-in-hand with its reputation for huge coal reserves and abundant power plants, the city was infamous for its murky skies and dirty streets covered in coal dust. No exception to the tide of urbanization that has swept the country over the past decades, Datong also faced a dilemma when it came to getting rid of the old to make way for the new, which sometimes meant tearing down historic architecture. As mayor of Datong between 2008 and 2013, Geng Yanbo, the sole protagonist of Zhou's documentary found himself caught up in controversy for his aggressive plan to demolish old houses. Many local Datong residents praised him for his industrious efforts to improve their living conditions, while others criticized him for recklessly dismantling historic relics or hurting the city's economic development.

“Using” (Long Ge) (2008) is about a twisted relationship develops between an urban Chinese couple struggling with heroin and a filmmaker chronicling their addiction. Zhou’s unflinching depiction of his friends’ repeated attempts to quit blurs the line between filmmaker and subject, and raises provocative questions about the ways in which each uses the other. Zhang Xianmin, a film producer and festival organizer, wrote: Zhou Hao always works on several productions simultaneously. While making Using, he was also filming other documentaries, including one about the cotton industry and another about young athletes. The central character in Using is known as Brother Long by other social outcasts. Originally from Northeast China, he makes his living dealing drugs in Guangzhou, and eventually he is trapped in drug addiction himself. He helps others, but also requests help from others all the time, especially from the filmmaker Zhou. But what Zhou offers cannot save him. The story is astonishing and thrilling. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

“Senior Year” (2005)is an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams in China. When it comes to anxiety about how the U.S compares with other nations, there’s always plenty to go around. But for a real wake-up call, nothing can compare to Zhou Hao’s Senior Year, an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams that will determine their destinies. Faced with mountains of memorization and rigid behavioral standards, most buckle down, but some rebel and some simply crumble under the pressure. Zhou brings tenderness, humor, and quiet outrage to this rare, behind-the-scenes look at China’s educational system.

Ai Xiaoming and Her Films

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: Ai Xiaoming is one of China’s leading documentary filmmakers and political activists. Since 2004, she has made more than two dozen films, many of them long, gritty documentaries that detail citizen activism or uncover whitewashed historical events. Among them are “Taishi Village”, which recounts the efforts of farmers to remove a corrupt party secretary; “The Epic of the Central Plains”, which tells the story of an AIDS village in Henan province; a five-part series on the 2008 Beichuan Earthquake that focuses on the efforts of activist Tan Zuoren; and, most recently, a five-part documentary on Jiabiangou — a labor camp for political prisoners where thousands died of famine in the Great Leap Forward. Still in progress, it already totals seven hours. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, September 8, 2016]

Ai grew up in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, daughter of Ai Renkuan, the adopted son of the Tang Shengzhi. In 1985 she moved to the capital to teach at Beijing Normal University, where she befriended many leading thinkers in China’s post-Cultural Revolution intellectual scene. In 1994, she became a professor of Chinese literature at Sun Yat-sen University in the southern city of Guangzhou, where she taught women’s studies and literature before retiring two years ago. She is the author of eight books on literature, and has translated works by Kundera.

“Jiabiangou Elegy: Life and Death of the Rightists (directed by Ai Xiaoming, 2017) is almost seven hours long. “Survivors of the Jiabiangou labor camp and their children recount the persecution of over three thousand people sent for re-education through labor during the Communist Party’s Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957- 59. Ai cuts the interviews into short slices and reorganizes them by theme, making it rich in historical facts and able to covers a broad range of different categories. “Garden in Heaven” (directed by Ai Xiaoming and Hu Jie, 2005) is about a mourning mother’s struggles for justice in a society that denies legal recourse for sexual violence.“After the date rape and murder of her daughter,

Ghost Town and Meishi Street

“Ghost Town” (Fei Cheng) directed by Zhao Dayong (2009) is about Zhiziluo, a town barely clinging to life. Tucked away in a rugged corner of Southwest China, the village is haunted by traces of China’s cultural past while its residents piece together a day-by-day existence. “Directed with scrupulous attention to detail, According to Manohla Dargis of the New York Times, “Ghost Town,” debuted at the New York Film Festival and “is one of the most important films to have emerged from the booming (but still unexplored) field of Chinese independent documentaries.

Karin Chien, an independent film producer, wrote: A remote village in southwest China is haunted by traces of its cultural past while its residents piece together their existence. The first Chinese independent documentary to screen at the New York Film Festival, Ghost Town elevated the Chinese digital documentary movement to new levels of poetry. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Dennis Lim wrote in Moving Image: “Ghost Town” is divided into three parts. It takes an intimate look at its varied cast of characters, bringing audiences face to face with people left behind by China’s new economy. A father-son duo of elderly preachers argue over the future of their village church. A twelve year-old boy scavenges the hillside to feed himself. Zhao’s novelistic yet urgent film attests to the filmmaker’s deep commitment to his subjects as well as the painful lives of those forgotten by the onslaught of development.

“Meishi Street” (Meishi Jie) directed by Ou Ning (2006) shows ordinary citizens taking a stand against the planned destruction of their homes for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Acclaimed at over two dozen museums and galleries around the world, Meishi Street, by renowned visual artist Ou Ning, works as both art and activism, calling worldwide attention to lives being demolished in the name of progress.

Chris Berry, a professor at Kings College, London, wrote: Cycles of demolition and construction have affected every Chinese urban citizen. The government owns the land, so they are powerless to stop the developers. But as Meishi Street shows, they do resist. Ou Ning gave restaurant owner Zhang Jinli a camera, and he uses it as a weapon in the battle for the control of speech in public space that the film shows is central to the campaign. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Karin Chien, an independent film producer, wrote: A landmark in activist filmmaking in China, Meishi Street shows ordinary citizens taking a stand against the planned destruction of their homes for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The subjects were given cameras to film their firsthand confrontations with the authorities.

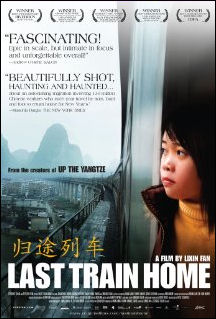

Last Train Home

“Last Train Home” (2009) explores the largest human migration on the planet by focusing on one couple, who represent their fellow travelers. Think about the rush to get home for the Thanksgiving holiday in the U.S. Now multiply that beyond imagination and you have a sense of the crush of 130 million Chinese workers seeking to return to their families each lunar New Year. A stunning documentary by Canadian-Chinese filmmaker Lixin Fan, "Last Train Home" explores the largest human migration on the planet by focusing on one couple, who represent their fellow travelers. Zhang Changua and Chen Suqin have left their teenage daughter and young son with Grandma to find jobs in the booming clothing manufacturing plants far from their home in rural Sichuan. The long absences take their toll on the family and lead to large gaps in values and expectations between the generations. In his rave review in the New York Times, A. O. Scott called "Last Train Home" a film "of melancholy humanism that finds unexpected beauty in almost unbearable circumstances . . . a story that on its own is moving, even heartbreaking. Multiplied by 130 million, it becomes a terrifying and sobering panorama of the present."

“Last Train Home” (Guitu Lieche) directed by Fan Lixin (2009): Yingjin Zhang is Professor of Chinese Literature at University of California, San Diego, wrote: A compelling picture of large-scale migration in contemporary China, this documentary enumerates the human costs of globalization by tracking both long-distance journeys and daily routines in the industrialized city and the hinterland countryside. Stunning images of huge crowds outside the railroad station during the spring festival and the persistent tension — even physical violence — between a teenage daughter and her parents raise serious questions regarding traditional value and human dignity in a changing society. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Scott wrote in the New York Times: “Fan, a Chinese-Canadian filmmaker whose guile and courage with the camera can seem almost magical, looks down at a throng of migrants pressing toward the train station in the southern city of Guangzhou. The crush of faces, possessions and umbrellas looks almost like an abstract composition, until you are in the middle of it, at which point it becomes chaotic and overwhelming. In what looks almost like a random encounter, Fan zeroes in on two individuals, a married couple whose travails will provide a painful, local illumination of a huge and complicated social phenomenon.” [Source:A. O. Scott, New York Times, September 2, 2010]

“Zhang Changhua and Chen Suqin, who come from a rural village in Sichuan province, have worked in the factories of Guangzhou for 15 years, stitching and bundling garments, sharing quarters in a dormitory and returning home each year to visit their children. Zhang Qin, their daughter, is a high school student when the film starts, and her younger brother is in middle school. The children live with their grandmother, who settled in the area when the Chinese government was sending workers from cities to farms, and who is part of a long cycle of sacrifice and suffering propelled by changes in state policy and shifts in the global economy.”

“It is clear that Chen Suqin and her husband want a better life for their children, but their way of expressing this desire sounds, to Qin in particular, like nagging and unfair criticism. Her mother pesters her to improve her grades, and she has trouble accepting the authority of a parent she sees only for a few days a year. Eventually — Fan’s story unfolds slowly and episodically over the course of about three years — the girl leaves school to join her parents in urban factory work.”

“But rather than bringing them closer together, this shared ordeal only highlights a generational chasm that can hardly be confined to this family. Qin’s parents cling to old Confucian values and sturdy peasant customs, living modestly and thriftily in the service of the future. But Qin is not content simply to produce consumer goods that will be sold elsewhere; she also wants a share of the pleasure that the modern economy promises. On her day off from the factory she goes shopping with some young co-workers, ogling and sampling items made by girls like them or parents like theirs.”

“Last Train Home” won the Golden Gate Award for Investigative Documentary Feature at the 2010 San Francisco International Film Festival and received the Best Feature-Length Documentary Award from the 2009 International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, the world’s largest documentary film festival. On one of the themes of the film Fan said: "China has become the world’s factory due to its cheap labor, but the question is: do people benefit or suffer from globalization?”

Lixian Fan and Making the Last Train Home

Ella Taylor of the New York Times called “The Last Train Home” “a quietly devastating documentary.” The film also won praise at the Los Angeles Asian-Pacific Film Festival and the Sundance Film Festival. Fan and a skeleton crew of three spent three years, on and off, making the film between 2006 and 2009. Fan who as born in Sichuan was 33 when the film was released in 2010. [Source:Ella Taylor, New York Times, August 27, 2010]

Ella Taylor wrote in the New York Times, “To gain the family’s trust Fan and his crew ate with them in their dormitory in Guangzhou, taught them how to manage their own wireless mikes, which they wore constantly, and would sleep on the pile of warm jeans the couple made while the crew waited to tag along after they finished their shift at midnight. So 15 minutes into the film, after that first train ride, he said proudly, we’d already known each other for a year. The mom once told me that they worked for 29 days, 15 hours a day straight, Fan said. The dormitories are right across the street from their factory, so it takes one minute exactly to go from their sewing machine to their bed. So that’s what they did for that month — sewing machine, bed, sewing machine, bed.”

“At home Zhang and Cheng encountered their deeply resentful daughter, Qin, 17, who rebels against her parents’ pressure to get the grades they see as her passport to a better life. At one point the simmering tensions come to a boil, forcing Fan to decide on his feet whether to intervene. The kids want more attention, and the parents are never around, he said. The parents know that education is the only way to, as we call it, jump out of the dragon’s door, out of poverty. But Qin, who is rebellious, independent and smart, did it her own way.”

“Fan belongs to a new generation of Internet-savvy filmmakers schooled in Western liberal ideas... His father was a college professor and projectionist, and Fan grew up watching foreign films. Like many of his generation, he broke with tradition by leaving home for Beijing, then gave up a prestigious job (My mom thought I was crazy) with the CCTV network, briefly relocating to Canada before working as a sound man and associate producer on the well-received 2007 documentary Up the Yangtze,about the mass displacements caused by the building of the Three Gorges Dam.”

Fan’s next project is a documentary about China’s green initiative focusing on a state-financed wind farm on the Silk Road in the Gobi Desert. He plans to shoot at a remote mountain school where Taoist philosophy originated and where they plan to recruit peasant children to teach them Tai Chi with martial art.

Karamay

Chinese director Xu Xin’s film Karamay documented the unfortunate story about Karamay, a town in Xinjiang, China, where 323 people including 288 students of elementary and junior high schools lost their lives in a tragic fire on December 8, 1994. The 6-hour documentary without any narration or musical score impressed audiences with survivors’ interviews: ‘someone demanded that everybody keep quiet; don’t move; and let the leaders go first.” Annoyed by this film, Beijing ordered local governments to block its showing.

Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films wrote: “Karamay” is a radical statement that ties the aesthetics of oral history to its own moral regard for its subjects. Capturing the testimonies of parents whose children were among hundreds who died in a tragic fire at a government event, Xu lets the camera run with minimal direction, rendering his camera in near-total service of his subjects, as if compensating for the years of neglect they’ve suffered in seeking justice following their tragedy. Seemingly spare in design and intention, the effect is immersive, compulsively watchable and undeniably devastating. [Source:Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

“One sentence centered my attention on this incident, and that was the instruction to the students to ‘stay behind, don’t move, let the leaders go first,” Mr. Xu, a former art teacher, told the New York Times. “That left a mark on my psyche.” Xu Xin said he hoped someday to have his films exhibited in Chinese theaters and on Chinese television. But, he added, making them is even more important than getting them shown. “I think my job is to supplement history, the official history,” he said. “Not many people are aware of the truth, of things that really happen, so to make a record for the future is the basic duty of a documentary filmmaker.”

Tape

“Tape (directed by Li Ning, 2009) is a riveting portrait of an artist’s attempts at expression and conflicts with societal norms. According to RADII: Director Li Ning documents years of his life attempting to find success as an avant garde artist. The result is a grueling film, which documents his familial pressure, whom he struggles to support, as well as the enthusiasm of the artists that he works with, all caught on film in this seemingly cathartic attempt by the director to understand his own artistic efforts. [Source: RADII]

Benny Shaffer, PhD Candidate in Media Anthropology, Harvard: Shandong-based artist Li Ning’s Tape challenges conventions in the documentary form, fusing performance art and autoethnography as it blurs the lines between over-the-top public spectacle and intimate private life. Shot on grainy DV tape, Li chronicles his avant-garde performance troupe’s three-year saga spent occupying public spaces with their outlandish, deftly choreographed performative interventions around the city of Jinan. His obsession with the material qualities of tape — its adhesive that binds objects and people together — resonates interestingly with the endless cataloguing of his personal life recorded on DV tape. This fragmented array of elements ultimately forms a highly unusual and surreal portrait of artists working on the margins of the art world in China.

Jian Yi and Super, Girls

Jian Yi

“Jian Yi is a filmmaker from China whose work actively engages ordinary citizens in documenting their own lives. He directed the critically acclaimed films “Super Girls!” and “Bamboo Shoots”, and co-directed the groundbreaking “China Village Documentary Project”, in which ordinary villagers from across China used video cameras to record the changing rural dynamics in their home villages. [Source: dgeneratefilms.com]

Jian Yi, who wasn’t trained as a filmmaker but worked at a number of film-related jobs such as editor, production assistant, producer, and curator for film festivals, is also the founder of the Participatory Documentary Center at Jinggangshan University and Original Studio, one of the nation’s first innovative community art centers. His documentaries and feature films, which reveal the social and cultural tensions of contemporary China, have won international awards and are shown worldwide. He is a 2010 Open Society Institute Fellow.

“Super, Girls!” (2007), directed by Jian Yi, China, follows ten teenagers on their quest to become superstars on China’s biggest TV show. Through candid interviews and footage of nail-biting auditions, the film offers a fascinating look inside what the Chinese media have dubbed “the Lost Generation.”

“Dong Sun” (“Bamboo Shoots”) won the Bronze Zenith Award at the 31st Montreal World Film Festival. “Chao Ji Nü Sheng” (‘Super, Girls!”) was inspired by a popular television singing competition with roughly the same name. On the latter Jian said, “I followed the competition as it took place...When I was unlucky, I got kicked out; but when I was lucky, everything went smoothly. I followed five participants mainly. Among them, Wong Yulan was the focus. I think she is a very interesting person. On the day that she passed the preliminary round of the singing competition, she noticed that there weren’t enough pencils to go around. She went to buy hundreds of pencils and then sold them to her fellow participants at the competition.”

Disorder and Floating

“Disorder” (Xianshi Shi Guoqu de Weilai) directed by Huang Weikai (2009) is a bold documentary mentioned as one of the best films of 2010 by Moving Image Source and Film Comment magazine. It won Best Documentary at the Ann Arbor Film Festival. Seeing it at the Reel China Film Festival in NYU, Hua Hsu of The Atlantic called it “one of the most mesmerizing films I’ve seen in ages.” One critic wrote: “The faster Chinese urbanization advances, the stranger peoples’ behaviors and moral standards become. Disorder combines more than twenty street scenes into a collage, revealing absurd facets of Guangzhou’s urban life, giving us an experimental film about the city, in the spirit of Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Camera.” [Source: dGenerate Films]

According to to RADII: Made in an effort to express the chaos, anxiety and violence at the heart of China’s major cities, Disorder takes footage from 12 different videographers to tell this tale of modern China.. Linda C. Zhang, PhD candidate, UC Berkeley: A documentary composed of various footage taken all across the city of Guangzhou by different cameras and different people. Utilizes montage to startling effect, and relentlessly shocks and exposes viewers to the chaos reflected in the black and white, grainy texture of the film content. Maya E. Rudolph, a writer, director and producer said: Disorder is a found-footage masterpiece shot by a fleet of amateur filmmakers in Guangzhou that weaves a hypnotic black-and-white texture of urban chaos. A raw, free-associative documentary exercise the often-hilarious fallibility of social structures, Disorder presently a brilliantly-coherent collage of a world that is anything but.

Karin Chien, an independent film producer, wrote: Huang Weikai's one-of-a-kind news documentary captures, with remarkable freedom, the anarchy, violence, and seething anxiety animating China's major cities today. Made from more than 1000 hours of amateur footage, Disorder reveals an emerging underground media, one that has the potential to truly capture the ground-level upheaval of Chinese society. La Frances Hui said: Huang Weikai meticulously assembles footage taken by amateur videographers documenting chaos, violence, and absurd happenings on the streets of China to create this pointed essay of urban mayhem.[Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Disorder

According to to the New York Times: “Disorder” is a piece of bricolage drawn from more than 1,000 hours of video, shot in large part by nonprofessionals working in Guangzhou and other cities in the Pearl River delta of southern China. They made their footage available to Mr. Huang, who then chose, edited and ordered the sequences he wanted down to just under an hour. “It’s like a chef who goes out to the market to get ingredients,” he explained when asked about the process he used in making the film, which shows scenes of urban chaos in which pigs wander onto a congested expressway, water mains burst, streets flood, the police beat vendors, and a baby is found abandoned in a garbage-strewn lot. “What he makes of those ingredients depends on him.”

The Chicago film festival described Disorder as a “gritty digital city symphony of Guanzhou? and “Vertov on acid?. Drawing on hours of footage from a network of amateur videographers, Huang summons a critique of whitewashed contemporary media and all-pervasive voyeurism. On why he made the film, Huang said: “I have lived in the city for a long time, and I have always been very concerned with city life. In recent years, cities have evolved a lot. This explains why I want to make a documentary about present city life in China. This film reflects what I think about city life, especially the chaotic side of it. On the film's Chinese title "Now is the Future of the Past,” Huang said, “I thought for a long time in vain about what name to give to this film. One day, I paced back and forth in my office and noticed a newspaper on the floor. It was the last edition of the year 2007. It summarized the accomplishments by Chinese artists in various fields of art. The introduction of the report was a standard piece that offered a review of the past and a vision of the future. The last sentence of the forward said, “The future is the constant arrival of the present.” Then I asked myself, what is the present? Isn’t the present the future of the past? That was how I decided to name my film.

“Floating” (2011) is another film directed by Huang Weikai: According to the Asia Society: A 30-year-old rural-born singer brings his guitar to Guangzhou to eke out a living by performing in public spaces. Like many migrant workers who don’t possess residence permits to stay in this southern metropolis, he is constantly dodging the authorities. The camera closely follows the singer’s daily life as he performs in pedestrian underpasses and lives out his tumultuous romantic life, which involves suicide, abortion and a bad break-up. As the film progresses, we find the filmmaker getting intimately involved with his subject’s precarious existence. Floating offers a humanist portrayal of those who drift on the fringes of society. [Source: Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

Wang Jiuliang and His Films About Plastic and Garbage

“Plastic China” (2016), a documentary by Wang Jiuliang, follows the members of two families in China who spend their lives sorting and recycling plastic waste imported from the United States, Europe, and Asia. Yijie, an eleven-year-old girl, works alongside her migrant parents from Sichuan in a recycling plant in Shandong while yearning to return home and attend school. Kun, the facility’s boss, aspires to buy a new car and to secure a better life for his family. Through the story of these two families, this poignant film explores not only waste recycling, but also social and gender inequality, urbanization, consumerism, and globalization. It won the Special Jury Award at the 2016 International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), the prize for Best Film on Sustainable Development at the 2017 Millennium International Documentary Film Festival in Belgium, and was nominated for Best Documentary at the 2017 Golden Horse Film Festival in Taiwan. [Source: Jin Liu, MCLC Resource Center Publication, May 2020]

“Born in 1976, Wang studied photography at the Communication University of China in Beijing, a preeminent institution for training journalists and media professionals. In 2007-2008, he completed a series of photographs about Chinese traditional folk religion. From 2008 to 2011, he investigated garbage disposal in and around Beijing and produced the documentary “Beijing Besieged by Waste” (2011) as well as a series of photographs with the same name. It took him six years to finish his second documentary, “Plastic China” (2011-2016), which earned him the Best Director Award at the 2017 “One World” International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in Prague. He now works as an independent filmmaker based in Beijing.

Wang told Jin Liu at an interview conducted at Georgia Tech University: “I was trained as a photographer, and have always been concerned about social reality in contemporary China. But when I tried to shoot reality, I found that photographic narrative has many limitations. When I started the project “Beijing Besieged by Waste”, at the very beginning I had mainly been taking photos. Soon, however, after two months of doing this, I was eager to embrace documentary filmmaking, something that integrates both the visual and the audio. Pictures were simply insufficient to tell the stories that I witnessed at those garbage dumpsites. Filming has more narrative power, and that’s how I finished my first documentary film. As for my second project, about imported plastic waste in China, the use of film became a natural choice for me. A film enables you to present a complicated issue more comprehensively, informatively, and sharply.

“I grew up in a rural village, so I have a special natural bond with earth and soil. Most of my work is related to space, or more specifically, to earth. In a sense, both of the films I’ve made so far are about geographic space. This has to do with my childhood experience, when I lived very close to nature. Before embarking on these environmental projects, I made a series of photos on traditional Chinese folk religions, entitled “Beliefs in Ghosts and Spirits”. They are art for the sake of art. But gradually I found there was a big gap between these beautiful pictures and the grim social reality. These images may be relevant to me, as some reflect the ghost stories that my grandma told me when I was a kid, but probably not to anyone else in this society. I need to face society, not ignore it. The documentary genre became a way for me to engage society.

On the making of “Besieged by Garbage, Wang said: In the summer of 2008, I returned to my hometown, a small rural village. I needed to find particularly clean natural environments to use as backgrounds for the photographs. But such places are hard to find now. Everywhere, covered by plastic tarps, there is the so-called modern agriculture, which has produced a countless number of discarded pesticide and chemical fertilizer packages scattered across the fields, ditches, and ponds. With the problem of garbage in mind, I started a videographic investigation of the state of garbage pollution around the city of Beijing in October 2008. My investigation revealed that 11 large-scale refuse landfills affiliated with the municipal environmental sanitation services system are scattered around the close suburbs of Beijing. Each landfill occupies tens of hectares of land, some of which have grown into mountains of garbage over 50 meters high. Out of concern for individual rights and interests, protests against these landfills have been steady; despite such efforts, the landfills grow taller and taller.

When Making “Beijing Besieged by Waste: “I discovered a whole community of persons who were making a living on garbage, building their houses from discarded construction materials, and wearing clothes they had gleaned in the trash. Many of their children were born there. These kids, they thought the world was supposed to be like this, a world full of garbage, dirt, and waste. And this world is what we, the adults, produced and left behind for our children, our next generation. It’s incredibly sad. As for the baby in figure 5, this was the first time he’d ever been photographed. He was sitting in a basin, which is auspicious; remember the Chinese term, jubaopen [a basin for gathering treasure]? With respect to the goats grazing over the KFC leftovers, in a sense, the human being is no different from these animals, both being fed with and consuming the same food. At the same time, you get a sense of how pervasive and invasive the global fast-food culture is. It’s ubiquitous.

Notable Independent Documentary Films from the Late 2000s

Among the more interesting documentary Chinese films made in the late 2000s, which were featured at the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Cinema, were “Ximaojia Universe” directed by Mao Chenyu (2009);“Survival Song” directed by Yu Guangyi (2008); and “Disturbing the Peace” directed by Ai Weiwei (2009). “1428" (directed by Du Haibin, 2009) is an award-winning documentary of the earthquake that devastated China’s Sichuan province in 2008. According to CNN: It explores how victims, citizens and government respond to a national tragedy.

“Please Vote For Me” (2007) directed by Chen Weijun: What would democracy look like in China? In Wuhan, a city in central China about the size of London, a third grade class experiments for the first time in selecting a Class Monitor through an election. As if nobody needs to be coached how to run an election campaign, candidates quickly go all-out to solicit votes from their fellow classmates. Backstabbing, bribing, bullying, fancy speeches — all sorts of aggressive tactics are employed to win votes. Tears are shed, feelings are hurt, and friendships are tested. What have these children learned from this experiment? Is democracy destined for exploitation? [Source: Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

“Children of the Chinese Circus” (2007) directed by Guo Jing and Ke Dingding takes a behind-the-scenes look at the training of some of the world’s best acrobats and circus performers. In this Shanghai circus school, a highly disciplined environment, small children endure excruciating and dangerous training regimes. Mostly from poor families, these children are sent to the school by their parents in the hope that the specialty training will secure them a future. While small children sustain agonizing daily practice, the teachers are also under tremendous pressure to produce award-winning stunts. A faculty meeting turns into a Cultural Revolution-styled criticizing session. This film is set to change your perception of acrobatic performances forever. "Recalling the finest nonfiction achievements of Frederick Wiseman”. Fiercely intelligent." [Source: Robert Koehler, Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

“Brave Father” (2007) directed by LiJunhu: Han Shengli has been admitted to a university in Xi'an. For his peasant family, this presents an incredible opportunity to move up the economic ladder. To pay for his education, the family sells off most of its valuable belongings. Shengli’s father also comes to Xi'an to find work in construction, while the son quietly collects plastic bottles on campus to make small change. The extremely shy son, who struggles to find a job upon graduation that pays better than his father’s construction work, is a sharp contrast to his old man, who is expressive and resourceful, and reads from a small notebook about his dreams for his son. While a brighter future is not yet in sight, he still believes all the sacrifices will eventually pay off. "An incredibly moving affair, with the determination of its characters offset and cruelly undermined by the harsh economic reality of the modern Chinese employment sector." [Source: James Mudge, Hollywood.com]

“Queer China, “Comrade” China” (2008), directed by Cui Zi’en, China’s most prolific queer filmmaker, presents a comprehensive historical account of the queer movement in modern China. Unlike any before, this film explores the historical milestones and ongoing advocacy efforts of the Chinese lesbian and gay community. A Shanghai Timeout Review of “Queer China, Comrade China” (“Zhi Tongzhi”) goes: "Espousing a more traditional form, and dividing the film in seven chapters, Cui covers incredible ground in a relatively short amount of time (60 minutes). Fact-filled, yet fun-filled, Cui’s film pays homage to all the tongzhi warriors, male or female, prominent or unknown, who are bringing about what Li (Yinhe) describes as a major sexual revolution."[Source: dgeneratefilms.com, December 2010]

“Readymade” by Zhang Bingjian (2008); How would you feel if your wife looked like Chairman Mao? Unsurprisingly, the cloud on the horizon of Chen Yan’s new career as a female Mao impersonator is her husband’s discomfort. The Mao cult was a major feature of the Cultural Revolution. And although, like Elvis, Mao has long ago left the building, he lives on in the form of Mao impersonators. Zhang Bingjian’s documentary shows just how far two of the many Mao impersonators are willing to go in their efforts to make their careers. Significantly, both of them are old enough to remember the Cultural Revolution Mao cult.

“Spiral Staircases of Harbin” (2008) was directed by veteran director Ji Dan. "On a hill in Harbin, in China’s Heilongjiang Province — the director’s hometown — a girl neglects her exam preparation in favor of drawing pictures. Her mother wants her to study. Below, a couple is unable to talk with their son who is always playing with his friends. The emotional lives of these powerless parents play out against the atmosphere of an unforgiving modern urban society. In the film Ju uses interviews to paint an intense, soul-bearing investigation of two friends from her youth, one poor and ill, the other middle class but stressed, set against Harbin’s symbol-laden cityscape."

“The Biggest Chinese Restaurant in the World” (2008) directed by Chen Weijun: Situated in Changsha, Hunan is the world’s biggest Chinese restaurant, which seats up to 5,000 diners and employs 1,000 staff. A sprawling complex containing pavilions in the style of traditional Chinese architecture, the restaurant is owned by Qin Linzi, a middle-aged female self-starter who used to earn 30 RMB a month. Documenting the restaurant’s day-to-day operation, the film shows routine slogan-chanting sessions intended to boost morale among the staff. A perceptive portrait of Chinese society, this engaging documentary provides a window into traditional Chinese customs that often revolve around banquets. "A fine example of what documentary film can be. It is fascinating, deeply entertaining." [Source: Todd Brown, Twitch]

“”The Village Elementary” (“Changchuan cun xiao”) by new director Huang Mei is a deceptively simple film about rural education and poverty. Huang’s honesty, her respect for her subjects,including a charismatically intellectual, politically aware, but sadly frustrated Sichuanese elementary teacher, gives the film a dirt-poor lyricism that tightly binds the minute details of individual lives to larger issues of political powerlessness and economic dependence. Liu Heng’s “Back to Daxian” (“Huidao Daxian” ) is also set in a school in Sichuan. This rambunctious, rough-hewn but sometimes shockingly vivid glimpse of urbanized seventh graders battling with their teachers, parents, and each other is compulsively watchable.” [Source: Shelly Kraicer, http://dgeneratefilms.com, 2010]

“Lao Ma Moved” (2009) is directed by Zha Xiaoyuan: "Rug-weaver Lao Ma and his family live in a remote village at Haiyuan County, Xi Haigu District, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. Rug weaving is a profession closely tied to traditional craft, but economic difficulties ensue as weavers’ families wrestle with marriage, childbirth, water shortages that ruin farming, and the hard fact of needing to travel away for work. The film reflects the poor living conditions of the Hui Muslim peasants in this mountain area.

“Mouthpiece” (2009), directed by Guo Xizhi, is an unusual film that takes us into the everyday life of a media organization in the southern city of Shenzhen. It unfolds in two parallel spaces: the Shenzhen TV news program “First Spot” and the city itself. At the TV station we see work routines of meetings, article writing, worry over viewing rates and market share, even lunch time napping. Out in the city, “the mouthpiece” news organ crews walk the energetic streets, recording people delivering their misfortunes to the camera while houses of immigrants are destroyed with thundering explosions.

“Once Upon A Time Proletarian” (2009) directed by Guo Xiaolu: Thirteen chapters provide poignant snapshots of individuals navigating the modern China. An old peasant calls his country ‘shit” and yearns for the old days when greed and corruption were less rampant; a young car washer from the countryside calls Beijing huge and unfriendly; a young woman at a hair salon wants to find a rich husband; businessmen sit around and chat about the prices of Russian prostitutes. This meditative film offers an existentialist take on the common experience of disillusionment and disorientation in an evolving social and economic landscape that is far removed from the bygone days of Mao. Filmmaker Guo Xiaolu is also a prolific writer. Among her works are A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers and 20 Fragments of a Ravenous Youth. [Source: Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

Notable Independent Documentary Films from 2010 and 2011

Chinese independent films became richly differentiated in the late 2000s and early 2010s. Some of the best and most groundbreaking ones in 2010 according to Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films were “Crossing the Mountain” (dir. Yang Rui); “East Wind Farm Camp” (dir. Hu Jie); “The High Life” (dir. Zhao Dayong); “No. 89 Shimen Road” (dir. Shu Haolun); “The Old Donkey” (dir. Li Ruijin); “Rivers and My Father” (dir. Li Luo); “Single Man” (dir. Hao Jie); “A Song of Love, Maybe” (dir. Zhang Zanbo); “Spiral Staircase of Harbin” (dir. Ji Dan); “ Triumph of the Will” (dir. Mao Chenyu); and “Winter Vacation” (dir. Li Hongqi). [Source: Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

“New Castle” (Xinbao) directed by Guo Hengqi (2010), according to Zhang Xianmin, a film producer and festival organizer, depicts the current condition of rural China. It is groundbreaking both in depth and breadth. A member of the post-80s generation, Guo Hengqi is a younger and lesser-known newcomer that I want to recommend.” “Sona, the Other Myself” (Goodbye, Pyongyang) is a documentary by Yang Yong-hi that explore questions of ethnic identification and solidarity, probing into the tragic ways in which national boundaries affect people’s lives and reminding us of the vital yet fragile efforts of those who seek to maintain human connections across national borders.

“Winter Vacation” by Li Hongqi (2010) is a film of quiet anger. Throughout its still mastershots, a many peopled cast passes in and out of this wintery town within Inner Mongolia. Terse and deadpan, Winter Vacation evinces a style recalling such filmmakers as Jim Jarmusch, Tsai Ming-Liang and Corneliu Porumboiu.

“No. 89 Shimen Road” by Shu Haolun (2010) is a poignant reflection of memory in the years leading up to Tianemen Square, No. 89 Shimen Road tells the story of one boy’s coming of age and the community that supported him on one street in Shanghai. Creating an eerie relay of stand-ins for the coming tensions within China throughout the 1980s the film finds urgency and a personal voice within the register of nostalgia. Conceived of as a richly textured fictional account of the time, the film weaves many elaborate devices including still photography and controlled film footage meant to evoke a document of the time, an elaborately recreated milieu. DVD

“A Love Song, Maybe” (2010), directed by Zhang Zanbo, is about a waitress who becomes involved in a relationship with a customer who comes to her for pleasure and escape. Their relationship, however, is plagued from the very beginning by lies, desire, impetuosity, confusion and pain. Shot among friends, the film creates an atmosphere of intimacy that alternates every day domestic life with the intensely emotional world of karaoke.

“When My Child is Born” (2010) directed by Guo Jing and Ke Dingding: Take a rare glimpse into the life of a young academic couple in Beijing. Jun is finishing her Ph.D. in Australia and is a Virginia Woolf specialist. Long, who has just returned from a research study in Germany, is struggling to finish his dissertation on Marx and Kant. An unexpected pregnancy propels the couple to marry quickly and navigate the world of parenthood. An overbearing mother-in-law enters their private world and expects to be in every part of child rearing. The film offers a candid and intimate portrait of two people caught between freedom and responsibility, career and family, and the new and old. [Source: Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

“New Beijing: Reinventing a City” (2010) directed by Georgia Wallace-Crabbe: Beijing has enthralled the world with major architectural wonders such as the National Stadium (Herzog & de Meuron), National Aquatics Center (PTW Architects), CCTV building (Rem Koolhaas), and National Theater (Paul Andreu). Behind the futuristic face of Beijing are old neighborhoods and hutongs (traditional narrow alleys) that have to be sacrificed for new developments. Heritage activist Zhang Jinqi and other volunteers scramble to document the fleeting old Beijing in a photography project. While Zhang mourns the past, major international architects express their visions for the renewed city. Working with a Chinese crew, Australian filmmaker Georgia Wallace-Crabbe captures the dilemma between development and preservation. [Source: Asia Society, September 25-October 29, 2011]

Documentary Films From the Mid 2010s

“When the Bough Break” (directed by Ji Dan, 2013) follows a family who scavenges a living from the landfills that once covered the city’s Daxing District. It show’s the family’s struggles against the vagaries of change and rapid urban development spreading across Beijing, “The Road (directed by Zhang Zanbo. 2015) documents how the construction of the Xu-Huai Highway in Hunan province has laid the landscape and many historical and cultural sites to waste. As this miracle of modern engineering takes shape, it offers an apt allegory for the dreams of a nation. [Source: Guggenheim Museum]

"Village Diary" (directed by Jiao Bo, 2013), according to RADII, provides a much needed filmic insight into life in rural China, Jiao Bo and his team spent over 1,000 hours filming over the course of 373 days to make this documentary, showing the remnant simplicity of life in this village, while also depicting the changes that China’s modernization has wrought on the country. Phoebe Long, screenwriter: The most interesting thing about the film is that it not only shows the actual situation of Chinese farmers making a living in the countryside, but also explores their spiritual pursuits outside of eating, drinking and sleeping. An old farmer who loves literature and art is often receiving complaints from his wife for not being pragmatic enough, but at a critical moment, his wife expresses her inner admiration for the old man. When the peasants begin to move beyond the practical, there seems to be a glimpse of hope for the arrival of civilization.

“Never Release My Fist” (directed by Wang Shuibo, 2015) reports on the punk music scene in Wuhan. Nathanel Amar, Researcher and director of the French Center for Research on Contemporary China in Taipei said: This documentary by the Sino-Canadian Academy-award nominated filmmaker Wang Shuibo is, without any doubt, the most thoughtful account of Wuhan punk history, centered on the charismatic singer of SMZB, Wu Wei. The documentary brilliantly retraces the complex history of Wuhan punk, by giving back the voice to a multiplicity of actors. Wang Shuibo also skillfully shows the personal and emotional sacrifices made by Wuhan punks, and Wu Wei in particular, in order to stay true to themselves and their ideals. As Wu Wei tells the audience at the end: “I will never spill my wine, and never release my fist!”

“We the Workers” (directed by Huang Wenhai, 2017) follows people in southeast China trying to organize workers into independent trade unions. It gives insight into the harsh working conditions that many Chinese people still face, as well as the fear and opaqueness surrounding labor laws. Karin Chien of dGenerate Films said: It’s a necessary counterpart to Netflix’s American Factory, which tells the story of American factory workers well, but presents Chinese workers as uninterested in worker rights. This one-of-a-kind vérité documentary closely follows the rollercoaster journey of organizing workers and fighting for collective bargaining rights.

“People’s Republic of Desire” (directed by Hao Wu, 2018) focuses on the rise of the internet economy in China, as well as the odd practices and living habits that have come along with this growth. Writer Krish Raghav said: “One of the best films made about contemporary China, about tech, and about how the lines between online and offline are blurred in late capitalism. It’s an extraordinary work on every front.”

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Ohio State University ; Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2021