SIX GENERATION OF CHINESE FILM

.jpg)

Dooman River The so-called Sixth Generation of Chinese filmmakers refers to a younger wave of directors that began making films in the 1990s and made some interesting low-budget films. Eschewing the lush cinematography and historical subjects of the Fifth Generation, which included Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige,, they instead have sought raw, straight-up depictions of contemporary China as it has undergone profound changes at lightning speed. Intitially these filmakers largely worked underground and some were been banned from working in China. Sixth Generation directors include Jia Zhangke, Zhang Yuan, Lou Ye, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Wu Wenguang — pioneers of China’s first independent film movement. Wang Bing, Li Yang, and Ying Liang are also included in the group

John A. Lent and Xu Ying wrote in the “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”: The Sixth Generation may be only a label, its definition openended because of the lack of a commonly shared manifesto or school of thought. Sixth Generation directors have their distinct individual tastes and their films all look different. They tend to move away from the Traditional roles of political dissident, illustrator of Chinese history, and reflector of the countryside, focusing instead on their own artistic visions. The locale of most of their films is the city in all its bleakness and rawness, since unlike the previous two generations, they have had little experience with rural China. Their protagonists are today's marginal people living outside the mainstream — rock stars, homosexuals, drifters. .[Source: John A. Lent and Xu Ying, “Schirmer Encyclopedia of Film”, Thomson Learning, 2007]

“Sixth Generation filmmakers themselves were marginalized. Born in the 1960s and 1970s, they grew up in a transitional period when Communist ideology deteriorated in the face of the rapid marketization of the Chinese economy. Thus, they do not allegorize their narratives; instead, they express their (and other urbanites') sense of loss, anxiety, and frustration in the face of China's quickly changing cityscape. Sixth Generation films explore in depth individual identities, penetrating the inner psychology of their characters. Some works are gloomily realistic, such as Jia Zhangke's Zhantai (Platform, 2000) and Zhang Yuan's Guo nian hui jia (Seventeen Years, 1999), or daring and restless, such as Wang Quanan's Yue shi (Lunar Eclipse, 1999) and Lou Ye's Suzhou he (Suzhou River, 2000).

Sixth Generation directors know censorship firsthand and have grown to live with it; at times, their works have been cut, banned, or relegated to limited release. Lou, for example, was not allowed to make films for three years, and his Suzhou River was banned. Sixth Generation directors' filmmaking has often been precarious because of government censorship and financial difficulties, yet many of their films have won awards at international film festivals.

The Sixth Generation have been helped by financial backing abroad. Wang Xiaoshuai’s "Beijing Bicycle" (2001) was funded with the help of French and Taiwanese studios and Lou Ye’s "Suzhou River" (2000) had producers in Paris and Berlin. By negotiating their own compromises with the censors in the Film Bureau, “Sixth Generation” have been able to get their films released films in China at movie theaters. Notable examples include Wang Xiaoshuai’s “Shanghai Dreams” (2005) and “Chongqing Blues” (2010), Zhang Yuan’s “I Love You” (2002) and “Little Red Flowers” (2006), Lou Ye’s “Mystery” (2012), and a number of films by Jia Zhangke, whose first censor-approved film was The World (2005). [Source: Shelly Kraicer, China File, January 17, 2013]

See Separate Articles: JIA ZHANGKE factsanddetails.com ; INDEPENDENT FILM MOVEMENT AND DOCUMENTARY FILMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RECOMMENDED AND ACCLAIMED CHINESE INDEPENDENT DOCUMENTARY FILMS factsanddetails.com ; ZHAO LIANG, HU JIE AND WANG BING: MASTERS OF CHINESE INDEPENDENT FILM factsanddetails.com

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Speaking in Images: Interviews With Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers” by Micheal Berry and Martin Scorsese Amazon.com; “The Cinema of Jia Zhangke: Realism and Memory in Chinese Film” by Cecília Mello Amazon.com; “Age of Global Capitalism: Jia Zhangke’s Filmic World” by Xiaoping Wang Amazon.com; “General History of Chinese Film III” by Ding Yaping Amazon.com; “Contemporary Chinese Cinema and Visual Culture: Envisioning the Nation” by Sheldon Lu Amazon.com; “Lights! Camera! Kaishi!: In-Depth Interviews with China's New Generation of Movie Directors” by Shaoyi Sun and Li Xun Amazon.com; “Painting the City Red: Chinese Cinema and the Urban Contract” by Yomi Braester Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Chinese Cinema Book” by Song Hwee Lim and Julian Ward Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com; “Chinese National Cinema” by Yingjin Zhang Amazon.com

Jia Zhanghe

Jia Zhangke Jia Zhangke, is arguably the most prominent figure of contemporary Chinese cinema and is regarded as the leader of China’s "Sixth Generation of Filmmakers", who make independent features outside the Chinese state system. Born in Fengyang, Shanxi in 1970, he is a director, writer, and producer, He began his career as a screenwriter and director in 1995 while studying Screenwriting and Cinema Studies at the Beijing Film Academy. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Jia is famed for such films as “A Touch of Sin”, which won best screenplay at Cannes in 2013, “Still Life”, which won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival in 2006, and “Ash Is Purest White”. According to the Wall Street Journal, his early works, including the underground hit “The Pickpocket” or “Xiao Wu,” focus on portraying the lives of people excluded from China’s economic boom. For many viewers outside the country, Mr. Jia’s movies are one of the most direct methods of understanding contemporary China.

In 1998, his first feature film, Xiao Wu, won the Wolfgang Prize and Netpac Award at the 48th Berlin International Film Festival. In 2006, Jia’s Still Life received the Golden Lion Award in the 63rd Venice International Film Festival. In 2009, he was awarded the Officer Order of Arts and Letters of France. Jia Zhangke’s main filmography as director includes: Xiao Wu, Platform, Unknown Pleasures, The World, Still Life, 24 City, and I Wish I Knew. Jia’s writings include: Jia’s Thoughts, Interviews with Chinese Workers, and I Wish I Knew — A Record of the Film. He lives in Beijing.

Jia began his career as an "underground" film-maker — directing movies that were praised abroad but never saw official release in China. Now he has a more amicable relationship with the government. He won the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival in 2006 — apparently earning the approval of then China's leader-in-waiting Xi Jinping. At 40 Jia became the youngest recipient of the Leopard of Honor for life achievement at Switzerland’s Locarno Film Festival. Organizers called him “one of the major revelations of the last two decades and one the greatest filmmakers working today.”

See Separate Article JIA ZHANGKE factsanddetails.com

Sixth Generation Films

Among the best Sixth Generation films “East Palace, West Palace” (directed by Zhuan Yuan, 1996) and prize-winning “Beijing Bastards”, “Beijing Bicycle” (directed by Wang Xiaoshuai, 2000) and “The Making of Steel” (directed by Lu Xuechang, 1996), "Unknown Pleasure" (directed by Jia Zhangke, 2002), "Devils on the Doorstep" (directed by Jiang Wen, 1999), .

Early “Sixth Generation” works from the early 1990s include Zhang Yuan’s “Mama” and “East Palace, West Palace”, Wang Xiaoshuai’s “The Days”, Wu Wenguang’s documentary “Bumming in Beijing: The Last Dreamers” and Lou Ye’s “Weekend Lover”. These films are credited with launching China’s independent film movement. The Sixth Generation’ works from the late 1990s include Lou Ye’s “Suzhou River” , Wang Xiaoshuai’s “Frozen”, Zhang Yuan’s “Seventeen Years” , Zhang Ming’s “Rainclouds over Wushan” and Jia Zhangke’s “Xiao Wu” .

Jiang Wen won the Cannes Film Festival Grand Prize (the second place award) in for “Devils on the Doorstep” in 2000. Shot in black and white, this film is a great, life-and-death comedy about peasants in a Chinese village during the Japanese occupation in World War II. The film was not allowed to be shown in China because it portrayed the Chinese villagers in a bad light and was too sympathetic of the Japanese.

Frozen (Wang Xiaoshuai, 1996) ia about an artist whose latest performance work is broken into three parts, with the final part an attempt at suicide by way of hypothermia. The story is often compared to the artistic chill after the Tiananmen Square incident in 1989, and was filmed by Wang Xiaoshuai using a pseudonym. The filmmaker Muhe Chen wrote: An artist trying to commit suicide during one of his performance pieces. A great film that addresses the early Beijing contemporary art scene during the 1990s. [Source: RADII]

“On the Beat” (Ning Ying, 1995) is the second in Sixth Generation director Ning Ying’s Beijing Trilogy, which explores the changes that the city went through during the Reform and Opening Up period, On the Beat explores the lives of urban policemen. Xueting Christine Ni wrote: With urbanization and migration across the country, the role of the police became a focal point. Ning Ying’s mockumentary On the Beat examines the idea of policing. [Source: RADII]

Jia Zhangke on Sixth Generation Cinema

Jia Zhangke said that he had not heard of the name Sixth Generation until 1992. However, he was aware of the works by directors such as Zhang Yuan, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Wu Wenguang before that. In 1992, when he was 21 years old, Jia was filled with intense feelings when heard a news article about Wang Xiaoshuai. In the article, Wang was said to have climbed onto a freight train bound for Baoding in Hebei Province to buy cheap black-and-white film stock. Jia was touched by Wang’s resourceful and audacious undertaking and deemed Wang one of China’s free-spirited dreamers who contributed a great deal to keeping the Chinese culture of the 1990s alive. [Source: Isabella Tianzi Cai, Southern Weekly, dgeneratefilms.com, July 2010]

Jia said. “I am not sure how one would define “the Sixth Generation.” In terms of age, I am seven years younger than Zhang Yuan, who directed “Mama”, and I am half a year older than Lu Chuan, who is believed to belong to “the Seventh Generation.” I made Xiao Wu when I was 28. From 1998 onwards people have thought of me as from “the Sixth Generation.” Like the group of people who left state enterprises to do private businesses, many of the independent filmmakers who turned their backs to institutionalized practices became acutely aware of their right for self-expression. Their works testified the credos of the independent film movement by introducing new angles of speech-making that necessarily expanded the freedom for expression and the freedom that people had in society in general. Therefore, I have always regarded the independent film movement as my first lesson on democracy.” [Source: dGenerate Films, translated by Isabella Tianzi Cai]

“During the reform era, many people were marginalized because they lacked power and money. Which of our films told the stories of these people? Which, amongst them, induced society to acknowledge their existence — helping the weak gain recognition “The Sixth Generation directors” films did. To me, their films are the gems of Chinese culture of the 1990s. It seems to us that films like this are not profitable, but why can’t we help the public accept them? Being a cinematic movement, “the Sixth Generation” has started to branch out today. Different directors have taken on different career paths. For one short phase of our film career though, each one of us presented the problems that we discovered in our daily lives, and we exposed our weaknesses in using the film medium. However, it is reassuring to me that most of us chose to film reality using a realist approach. The films that were produced complemented and resonated with one another, sketching out the revolution that took place in China’s film art, leaving behind a trace that would have otherwise lost in a consumer society. This trace is also a scar, leaving a pain behind, in history and in us.”

Jia has suggested that only films that present the true stories of China’s reform were able to offer a strong foothold for people living in today’s volatile and materialistic world. He argued that in order to produce this kind of story, filmmakers would need to withstand the pressure of a market economy. He pointed out the irony that today, whenever a new independent film is out, the media like to mention the box office results of similar independent productions in the past. Before the film is even exhibited, they prognosticate its failure.

Jia Zhangke on the Forces Behind Sixth Generation Cinema

Jia said: “Political tumult was not yet in the distant past for Chinese people in the early 1990s. In the aftermath of trauma and engulfed by societal-wide depression, the so-called ‘Sixth Generation” directors used film to challenge the authorities. I was especially thrilled by the “independent” label that they carried...I was a follower of “the Sixth Generation,” and I regarded them as my teachers. I knew that they formed the oppositional force against the authorities, and they were doing everything they could to fight for the freedom for self-expression. Many years later, when I heard others referring to them as an unfathomable community, quixotic Don Quixotes, and ill-timed and deviant monsters, I laughed.”[Source: dGenerate Films, translated by Isabella Tianzi Cai]

“I still remember vividly one passage from the newspaper that I bought. It was said that for his film The Days, Wang Xiaoshuai climbed up onto a freight train bound for Baoding in Hebei province to buy cheap black-and-white film stock. I have always imagined it in my head that in those days, the young man must have looked nothing like the puffed old man now; he must have been robust and exuberant. Amongst the numerous howling trains that traversed the bustling Hebei plain was one that once carried a young man with the dream to make films...At the time, majority of Chinese were not aware of their agency and did not think much about using film for self-expression. There were 16 state-run studios. Only they had sufficient financial support and grants to make films. All the other film productions were considered “illegal.”

“From the 1990s we began to hear individuals’ voices outside the official rhetoric, and they were injected with the independent spirit. Today, ordinary people can assert their self-esteem. Shouldn’t we then thank “the Sixth Generation” directors for having directed their attention to the lower rung of society, representing marginalized people, and advocating the restoration of basic human rights to them? Of course, film is not the only force that advances society, but in retrospective, film was the battleground where culture and outdated doctrines played out against each other. Many were banned from making films domestically; some had their passport confiscated too. Yet, many continued to make films, despite having those who stood alongside the authorities laugh at and mock them.”

“I cannot forget the day in 2003 in Beijing Film Academy where it was announced that the majority of “Sixth Generation” directors who had been banned from making films previously could make films again. A government official added that, although the government lifted the ban, we should realize that our works would soon go underground in the market economy. During the six years after the incident, I experienced the tyranny of the market. However, that does not mean that I became antagonistic towards the market, because a market economy is part of the dream of freedom. We do not want to complain about anything. We know that there are insidious deals made behind the scenes with people with power, but we embrace the market, and we are prepared to devote ourselves to this cause till our last breath and penny.”

“What is most ironic is that every time we sell a film, the media are extremely sensitive to our box office history, and they like to sentence our films to death before the films even hit the screen. Art films need a relatively long period of time for the market to warm up to them. For a month or two after their releases they can still be in the fermentation stage. When the media prognosticate that these films would have disastrous box office returns, directors will be hit hard and victimized. Since there is not even a three-day period to get warmed up, potential viewers will walk. Nobody wants to watch dead corpses whereas everybody wants to see miracles.”

“We have survived in the battlefield of the market economy. I am willing to belong to the imperishable ‘sixth Generation.” Although this movement has drawn to an end already, there is still a long way for each of our careers. After the French New Wave, Truffaut became a great commercial director, with an outstanding box office record; Godard became an auteur; but most New Wave directors fell somewhere in between. Personal failures and successes cannot speak for a generation. Conversely, the negations of one’s generation cannot be used to speak against him or her. Doing so would be outdated.” No matter what happens, we will always be loyal to cinema. If you are willing to accept culture as an integral part of film, I will say to you, for the past dozen years or so, all the best films that have tried to embrace culture are made by the Sixth Generation filmmakers. It would be hard to imagine that without their seminal works how we would extend our culture into the future or what we could offer to the world as ours. Because of them, China’s film culture is still alive and breathing.”

Lou Ye and His Early Films

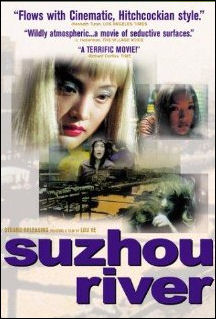

Shanghai-born Lou Ye (born 1965) made the visually stunning “Suzhou River”,“Purple Butterfly”, “Summer Palace” and “Spring Fever”. He has had a successful career as an international festival filmmaker, even though several of his films have been banned by the Chinese government, One ban was imposed after an unauthorized screening of his very unauthorized Summer Palace (Yiheyuan) at Cannes in 2006. His first two films, "Weekend Lover" and "Suzhou River", were banned in China,

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times:“Over the years, Lou has suffered repeated censorship at home and enjoyed a growing reputation abroad. Officials from China's State Administration of Radio, Film and Television banned his first film, "Weekend Lover," for two years. "Summer Palace" — which chronicled a generation's political awakening and disillusionment amid the pro-democracy protests that led to the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown — was submitted to the Cannes festival without government approval in 2006, and afterward Lou was prohibited from filmmaking for five years. He defied the ban to make "Spring Fever," about a doomed gay affair, and the film won best screenplay at Cannes in 2009. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 18, 2012]

After his film "Mystery" came out in 2012, Brice Pedroletti wrote in the The Guardian: The return of the enfant terrible of Chinese cinema was bound to cause a stir. He had been banned from making films in his own country for five years.That was not the case with Mystery, however. When it was screened in the Un Certain Regard section of Cannes it had received the seal of approval from the State Administration of Radio, Film & Television (SARFT). Lou Ye had even joked that the film had all the necessary authorisations to leave China "unless there's been a last minute hitch". He never thought for a minute there would be. The script and the Cannes version of Mystery had been passed after intense negotiations with the supervisory bodies. According to Nai An, who produces most of Lou Ye's films, "We had to do a lot of explaining and communicating. This time we were prepared, since we knew they would be very cautious with this film." [Source: Brice Pedroletti, The Guardian, November 20, 2012]

Lou Ye Films

“Suzhou River”, directed by Lou Ye, (2000) is a mysterious, modern noir film that finds its visual inspiration in the watery channel that runs through Shanghai, and takes its narrative framework from Alfred Hitchcock’s "Vertigo". At its center is the unseen videographer through whose eyes the film unfolds. One actress plays two women, who an obsessive love is unable or unwilling to tell apart. She is both Meimei, the videographer’s girlfriend and a "mermaid" at a sleazy tropical nightclub, and Moudan, a businessman’s teenage daughter who is in love with a motorcycle courier working for her dad. No good comes from this convoluted plot, but as the Village Voice’s J. Hoberman observes, director Lou Ye "has transformed Shanghai into a personal phantom zone . . . making a ghost story that shot as though it's a documentary — and a documentary that feels like a dream."

“Love and Bruises” managed to secure a premiere at the Venice Film Festival sidebar Venice Days. According to the festival: Lou Ye is perhaps the most prodigiously visually gifted of his sixth generation colleagues. His films have sustained a remarkably daring (in a Chinese cinema context) interest in the political erotics of relationships; Lou is willing to venture into the kind of dark, sexually mature material that few of his Chinese colleagues know how to explore. Love and Bruises features a deliberately inexpressive Chinese female lead who is in love with inarticulate French brute who abuses her, forces her, cheats her, and pimps her to an even more violent rapist-friend. She also cooks and cleans, between frequent bouts of fucking that are shot far too tamely to hint at the kind of feral circulation of sexual desire that might account for the persistence of the couple's relationship.

"Mystery" (2012), Brice Pedroletti wrote in the The Guardian, is a story of a love triangle that turns to tragedy against the smoggy backdrop of Wuhan, taken from a woman's real-life account about her unfaithful husband that caused a stir in China in 2009. This is Lou Ye's seventh film but only the second (with Purple Butterfly in 2003) to have been released in his own country. Mystery is beautiful and violent, both in the emotions it deals with and the scenes that display them. It echoes some of contemporary China's own problems, such as corruption, money, ambiguity and morality. And yet as the French co-producer Kristina Larsen of Les Films du Lendemain put it, you could almost think you were dealing with some bobos from Massachusetts. She explained that since there are no film-rating categories in China, Lou Ye had made the necessary concessions for the domestic version, such as adding a text at the end explaining that the two protagonists involved in the crime were later arrested by the police. That was left out at Cannes. [Source: Brice Pedroletti, The Guardian, November 20, 2012]

“Blind Massage”, directed by Lou Ye, won six awards, including best feature film in 2014 at the the 51st Golden Horse Awards in Taipei., the film explores the lives of a group of blind massage therapists in Nanjing. The film also picked up awards for best new performer (actress Zhang Lei), adapted screenplay, cinematography, film editing and sound effects. [Source: Real Time China, Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2014]

“The Shadow Play” (Lou Ye, 2018) is Lou’s ninth film. According to to RADII: Lou Ye’s stature as a probing, uncompromising director has never been in doubt. “The Shadow Play” is an interesting blend, with the lead character seeking out the truth behind a brutal death, and uncovering a web of conspiracy, against the steamy backdrop of South China. Ffilmmaker Muhe Chen wrote: A very Lou Ye-style movie scripted from a real story about a murder caused by a conflict between a real estate investor, his government partner, and their spouses. The story, in my view, is an epitome of the distorted psychological landscape under corruption and morbidly-developing capitalism in China, but Lou Ye narrates it with a very romantic touch. [Source: RADII]

Lou Ye Blogs About His Battle with Censors

"Mystery" (2012) was the first film by Lou Ye to be screened in China for 10 years It was presented at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2012 and released in China the following October. When Lou sought to get the French co-production through China's censors, he was asked to make many changes. He took the unusually confrontational approach by blogging about his battle with the film bureau.

Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “"Mystery" looked like a chance for the director come in from the cold. Lou received approval from China's censorship body before screening his movie at the Cannes. After the festival, he registered the $2.6 million noirish tale, made with 20 percent French financial backing, as an official French-Chinese co-production. But weeks before the opening of "Mystery" in Beijing, Chinese authorities told Lou to edit two scenes containing sex and violence. In China friction between filmmakers and government regulators is a regular occurrence, yet often, the difficult back-and-forth takes place behind closed doors. This time, Lou took the fight public, posting documents online and blogging for weeks about each interaction and negotiation with authorities. The skirmish raises unsettling questions about Chinese officials' willingness to scuttle business deals and impose new censorship requirements, even after issuing approvals. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 18, 2012]

“"Mystery" centers on a wife's discovery of her husband's affairs, and touches on some potentially sensitive subjects like the behavior of police. In his postings on Sina Weibo — the Twitter of China — Lou said officials had asked him to reduce the number of hammer blows in one bludgeoning scene from 13 to 2.“"This is the Chinese way. It's not good, but this is the way," Kristina Larsen, the French producer on "Mystery," said in a phone interview from Paris. "Basically in France, no one wants to go into co-productions with China — you have this different culture, and all the censorship. It's too complicated."

“After two weeks of negotiations, Lou was able to declare a victory of sorts: He agreed only to darken the final three seconds of the bludgeoning sequence. And, to voice his displeasure, he said he would remove his name from the credits on the film — though it still appears on posters and other promotional materials.

Wang Xiaoshuai

Wang Xiaoshuai is best known for his portrayals of urban life and social dislocation in films such as “Beijing Bicycle” (Shiqisui de danche, 2001), the story of a villager's relentless struggle to get his bicycle back in the exploitative and violent urban environment. Wang's “Chongqing Blues” debuted at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. He also directed the political film “Shanghai Dreams” (Qing Hong, 2005), in which a family of Guizhou residents dreamed of returning to their Shanghai homes.

On "Chongqing Blues." Maggie Lee wrote in The Hollywood Reporter, “Flowing with the same pensive, heavy cadence of the river that visually and metaphorically dominates the film, it is an old style exploration of the new face of China through an itinerant father's return to the titular city to make sense of his son's death after abandoning his family for 15 years. It may be solidly directed with Bressonian detachment and anchored by an absorbing performance by lead actor Wang Xueqi, but it is neither outstanding nor revelatory enough to play outside of a cluster of European art house cinemas.” While away on a long voyage, ship captain Lin Quanhai (Wang)'s 24-year-old son Bo (Zi Yi) was shot by police for a random stabbing and hostage taking incident in a mall. Lin left his native city Chongqing when Bo was only 10. He goes back to talk to those involved in the case or close to Bo's life in order to understand the circumstances of his death...Lin's journey is both that of an errant father taking stock of his guilty past and the return of a prodigal son to his hometown to find himself an outsider. ...The city's grungy character is captured by a roving handheld camera that follows Lin's from behind as he wanders around muggy streets strewn with dank and weathered buildings, always teeming with scruffily dressed crowds wearing stressed out frowns. These downcast images are intermittently juxtaposed with splendid wide shots of the riverside cityscape, veiled in layers of fog and haunting compositions of a pier filled with scrap construction vehicles. [Source:Maggie Lee, The Hollywood Reporter, May 13, 2010]

Wang Xiaoshuai's “11 Flowers” (Wo shi yi) received its world premiere at Tokyo International Film Festival. Wang's own opening voiceover announces that this this work is based on autobiography: it is certainly his most personal film to date. It is also his most successful film in ten years. Set in 1975, one year before the end of the Cultural Revolution, in Wansheng, a small town in the Chongqing region of Sichuan, it parallels his own youthful experiences while an eleven year-old growing up in China's interior. His parents, like his stand-in in the film, Wang Han's, were relocated, along with many other former Shanghaiers, to remote interior cities in the early 1960s. This was part of Mao Zedong's "third front" policy of establishing safely remote bases in China's interior for strategic industries under what was perceived to be the threat of Soviet invasion. These displaced urban communities contained many members who retained a strong sense of their previous urban identities while living in this sort of internal industrial "exile". In the film, Wang Han, his eleven year-old fictionalized self, along with four classmates, navigates through a community riven by political, sexual, and familial tensions. Despite the stated urgency of facing reality, Wang Xiaoshuai has opted for a smooth, seamless, fictionalized packaging that transforms his lived experience into something like an idealized, perfectly well-designed, impeccably dramatic whole.

“Red Amnesia” (2015) was described by the New York Times as "part mystery, part observational drama" and said it "takes on the issue of selective memory of the 1966-76 Cultural Revolution in present-day China." It received largely favorable reviews from critics and moviegoers in China and at the 2014 Venice Film Festival, where it was shown in the main competition, but Wang complained it was held back by competition from big Hollywood films. According to the New York Times: the film “secured less than 2 percent of the country’s total movie screenings on its opening day, earning about $130,000 at the box office, according to the film data site 58921.com. On its peak day, May 7, the film had 4,045 screenings, or about 3.25 percent of the national total. By contrast, “Avengers: Age of Ultron” had 77,498, or 66 percent of total screenings, at its peak. “Since its premiere on April 30, “Red Amnesia” has pulled in just over $1.4 million at the box office, according to the movie website Mtime.com. Over the same period, “Avengers: Age of Ultron” passed the $200 million mark in China. [Source: Amy Qin and Chang Chen, Sinosphere, New York Times, May 29, 2015]

Yiang Liang, The Other Half and When Night Falls

Ying Liang is sometimes named as a Sixth Generation filmmaker. “The Other Half (directed by Ying Liang, 2006) was listed as a Top 10 Film by a naumber of critics The The New Yorker called it a “fierce and harrowing cry of political rage.. Variety said it was: “One hell of a beautiful film. Endlessly haunting with serene, even joyous consciousness that is the opposite of despair. The China expert Ian Johnson also likes it very much. He said the film offers a withering portrait of life in a modern industrial town.

“When Night Falls” by Ying Liang has a Chinese title, which literally translates to “I Want to Say More”. Shelly Kraicer “Quite possibly the darkest Chinese film of the year, and one of the most important, it is based on the real life case of Yang Jia ,sentenced to death for the 2008 knifing murder of six Shanghai policemen, the film has drawn the hostile attention of Shanghai’s police, who exerted considerable pressure on the director and on the producers to suppress the film both inside and outside China. But Ying Liang, whose subtle, ironic indie films make him one of the most incisive young Chinese directors working today, has not made this an explicitly political film. Instead, he adopts an oblique, fictional mode, concentrating exclusively on the killer’s mother, Wang Jingmei (played with powerful restraint by Nai An), her struggle to understand her son’s actions and her subsequent victimization by a criminal justice system that is opaque and oppressive. [Source: Shelly Kraicer, China File, January 17, 2013]

“When Night Falls” is about Yang Jia, a young man who, after suffering abuse at the hands of the police and then entered the local police station and stabbed six officers to death. Ying has effectively been exiled as he faces arrest if he ever returns to China. Richard Brody wrote in The New Yorker: “Ying doesn’t show the killings themselves — there’s no bloodshed on-screen. Rather, the story is centered on three days in the life of the accused’s mother, Wang Jingmei, who, at the time of her son’s arrest, is also, in effect, arrested — essentially kidnapped by the government. She is charged with nothing and forcibly confined in a mental hospital, confronted by her son’s so-called attorneys and compelled to sign official documents, and then returned to her Beijing apartment two days before her son’s execution. But by the time of her release, her son has already become something of a folk hero and his case has become a cause célèbre among daring activists (including the artist Ai Weiwei) who are willing to challenge the authorities in court and online. When she returns home, a group of them — including a documentary filmmaker — is awaiting her. [Source: Richard Brody The New Yorker, May 24, 2013]

“Ying’s decision to avert the filming of violence in favor of a drama of legal maneuvering and personal grief fills the calm and contemplative frames with the ambient menace of ubiquitous power. From the announcements on public loudspeakers of the “splendid Olympic games” to the severe but sham formalities of the courtrooms, Ying depicts a society in which secret official force turns the air as thick and weighty as water. He’s a filmmaker of law and apocalypse, and the catastrophes that, in his earlier films, arise from (and symbolize) corruption, mismanagement, and cavalier indifference are here reflected, off-screen, in Yang’s execution, the irreducible and natural end result of government authority. Jia’s tender compassion for the law’s victims is simple and touching: ultimately, he suggests, there’s no such thing as making good on an injustice once committed, and the impotence of the law to aid its victims leads to a quietly radical and absolute desperation. The movie has been banned in China, and, worse, Ying is a subject of a vicious legal campaign that has sought, first, to suppress and destroy the film itself, that has threatened members of his family, and that has resulted in his exile.

Black Coal, Thin Ice and The Wild Goose Lake

“Black Coal, Thin Ice” (Diao Yinan, 2014) won the the Golden Bear — the top prize — at the 64th Berlin International Film Festival. Liao Fan won a Silver Bear for Best Actor. It is bleak tale of a murder, in which Liao Fan’s detective tries to piece together the mystery of a dismembered corpse. Liao plays a washed-up overweight ex-cop investigating a series of murders in northern China. Liao said he put on 10 kilograms to play the role.“ He was the first Chinese actor to achieve the best actor honor at Berlin. The film won a Silver Bear for Best Script. “Cinematographer Zeng Jian won the Silver Bear for Outstanding Artistic Contribution. [Source: Wei Xi, Global Times, February 17, 2014]

According to RADII: Having attracted attention with his first two features, director Diao Yinan’s third movie “Black Coal, Thin Ice” was a sensation. Diao has been integral in introducing a more commercially viable, higher budget style of arthouse film to China, with this and his most recent title “Wild Goose Lake” getting a wide cinema release, the latter bringing in around $30 million at the box office. Xueting Christine Ni, author and speaker: About the less savory side of contemporary Chinese society, the gritty social satire and black comedy has evolved from the beginning of this century into a tradition that’s one of a kind in the world. [Source: RADII]

“The Wild Goose Lake” (2020) a film-noir film by Diao Yinan, with influences from Francois Truffaut, Robert Bresson, Chen Kaige and Jia Zhangke, starring Hu Ge and with a plot worthy of Raymond Chandler, was a Chinese box office hit. James Mottram wrote in the South China Morning Originally written before Black Coal, Thin Ice, Diao put it aside because he was not satisfied by the direction the script had taken. Then a news report about a so-called “Congress of Thieves” in Wuhan, central China, around 2012 helped him shape the story. Criminal representatives from important sites in each Chinese province gathered to exchange experiences and divvy up territories — until they were caught. [Source: James Mottram, South China Morning Post, January 8, 2020]

“Diao used this “congress” as a central idea in The Wild Goose Lake, in which gangsters come together in a seedy hotel basement to learn about the art of mass motorbike theft. “We do have these motorbike-stealing gangs that are very prominent in certain parts of China, especially suburban areas and small villages,” says Diao, who decided to “combine” this with the idea of a multi-province criminal network. In Diao’s hands, this coming together of gangsters is the starting point for a fiendish, flashback-riddled, rain-lashed film noir so complex it would probably give American crime writer Raymond Chandler a headache were he alive today.

Robin Weng and Fujian Blue

“Fujian Blue” is an acclaimed film by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). Andrew Chan wrote in The Auteurs: “”Fujian Blue” explores the aspirations of mainlanders who would rather be anywhere than where they are. The province of the film's title has historically been a launching point for Chinese immigrating to other countries, and Weng's film is equally convincing when it sympathizes with the desire for mobility and critiques the materialism that often instigates it. Though it begins amid seedy settings and bawdy humor, Fujian Blue slowly reveals its emotional sophistication, building toward an unexpectedly devastating ending.” [Source: Andrew Chan, The Auteurs, March 4, 2010]

“Fujian Blue” (“Jin Bi Hui Huang” ) is ‘split down the middle: the opening plot involves a group of young gangsters who try to swindle “remittance widows” whose husbands are living abroad; the second narrative follows a young man's dashed dreams of smuggling away to a better life in England,” Chan wrote.

Mike Fu, a graduate student in Chinese cinema at Columbia University, wrote: Featuring idyllic natural landscapes side by side with Fujian province’s urban sprawl, Weng’s narrative follows a group of young hoodlums circulating carefree in a vapid nightlife of karaoke bars and dance halls. By day, they pursue a more malicious endeavor to extort money from local housewives, whose husbands have made their fortunes abroad and left them floundering at home.”

“Far from the reach of Beijing’s tendrils, the ne’er-do-wells seem to flaunt this lack of governmentality with abandon were it not for a few run-ins with the law. Only then does their uneasy relationship with the state come into focus, but it’s brushed aside just as quickly in pursuit of their dreams to find wealth overseas. We’re told at the very beginning that Fujian is notorious for its human trafficking operations, run by snakeheads who collect gross sums of money in exchange for passage to a new land. It is this transitory sense of being in-between that renders the social fabric unstable and nearly illusory.”

‘stunning cinematography and understated acting merge for a rapturous experience in Fujian Blue. Weng’s directorial debut reveals an up and coming talent whose keen aesthetic sensibilities become the vehicle for a vibrant portrait of freewheeling youth culture in China today.

Liu Jiayin and Oxhide and Oxhide II

Director Liu Jiayin is considered one of the most talented woman filmmakers in the world, and an important voice from the new generation of China’s independent filmmakers. She made her first feature film “Oxhide” in 2005 when she was only 23. She made “Oxhide II” in 2009. The Chicago Doc Film Festival described Oxhide (2005) as one of the most important Chinese films in the past decade and a monument of world cinema: “Oxhide is a brilliant paean to the powers of formalism. Liu Jiayin cast her parents and herself as fictionalized versions of themselves. Through the thousand daily travails of city life, a genuine and deeply moving picture of Chinese familial solidarity emerges from the screen.”

"Oxhide" focuses 0n Liu’s family, according to RADII "depicting their daily lives within an impossibly small apartment. The film takes a seemingly mundane topic and transforms it into something huge, and emphasizes the possibilities of film on a tiny budget. Writer and producer Samantha Culp said: I’m a bit biased because I got to work with Liu Jiayin, and she’s amazing, and that made me respect her even more. But I became aware of her because of this film. It just blew my mind in terms of the possibilities of domestic documentary. It makes so much other arthouse documentary look so convoluted and overly pretentious because it’s both so simple and so mysterious, and so strange, about the textures of her everyday life with her family. To this day I’m not entirely sure — it is scripted to a degree, but there is something that’s kind of magical about it. It makes the interior of one’s own family and domestic home seem really strange, like you’re encountering them for the first time. It’s one of the most unique films I’ve ever seen. [Source: RADII]

Oxhide II (2009) breaks new ground in cinematic art. Liu Jiayin’s follow-up to her masterful debut Oxhide turns a simple dinner into a profoundly intimate study of family relationships. Building on the stunning vision of Oxhide, writer-director Liu Jiayin once again casts herself and her parents in scripted versions of their life in a tiny Beijing apartment. At the same time, “Liu’s shots are carefully, rigorously, exquisitely composed” (Berenice Reynaud, Senses of Cinema).

The Global Times reportedl: “Liu Jiayin reveals all in her autobiographic film “Oxhide” in which her father tries to bully her into growing taller by forcing her to drink milk, and also urges her to hang from a pull-up bar. Her mother, also concerned she isn't flowering into a curvy woman, urges Liu to dress more daintily, like a Japanese girl.” Liu based the script for the emotionally taut Oxhide on some of the most sensitive moments in her family's life, and had her mother and father play themselves. It was shot with a single stationary camera, using very long takes. Other people might be distressed by having the world know their most intimate stories, but this doesn't seem to phase Liu, who has made Oxhide II and is currently finishing the story for Oxhide III.” [Source: Hao Ying, Global Times, August 4, 2010]

“Oxhide II took a more formalistic approach, with the carefully crafted script calling for a series of long shots as the family makes dumplings, exploring their dynamics in a more gentle and subtle manner. Oxhide III will focus on the difference between the real life and the interior world or imagination of her family.” “Liu maintains her movies have had no effect on her family ties, despite the intimate scenes, which, for example, call for her father to play himself verbally bullying other family members. After all, she says, her family has been quarreling about those things for years.”

Shanghai Timeout said: Oxhide II — pushes the previous film’s formal radicalism one step further: it breaks down an even smaller domestic space and its 133 minutes into nine shots of uneven lengths and varied angles that go around the table in 45-degree increments (performing a complete 180-degree match). Within this minimalist framework, several layers of emotion/narration intersect. Liu’s shots are carefully, rigorously, exquisitely composed. What is even more amazing is how tension is expressed within the frame, how every gesture, every verbal exchange reorganize the balance of power between the three protagonists.”

Bi Gan Films

According to RADII: Bi Gan might be the most experimental and interesting director in China today. His first film, “Kaili Blues” (2016) was a revelation, using a 41-minute long shot. His second, “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (2018) provided more talking points, initially perplexing Chinese viewers, who were not expecting a dark, moody noir film, but rather a classic romance. The film went one step further than Kaili Blues, making use of a 59-minute long take. [Source: RADII]

On “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” (Bi Gan, 2018), Writer and producer Samantha Culp wrote: This is the first 3D film I have ever cared about, and could be the last — it will be near impossible for anything to top it. Yes, its characterization is thin and opening half is molasses-slow — but that’s ultimately all on purpose, lulling the audience into a near-REM state to be prepared for the second half, a 59-minute unbroken single take filmed in 3D that floats through and around a nighttime village in ruins as a noir-ish antihero searches for a mysterious woman. Besides being technically brilliant, the sequence may capture the dislocated experience of late 2010’s reality (in China and elsewhere) better than any other — the suspended logic of a dream.

On “Kaili Blues” (Bi Gan, 2016), Shelly Kraicer wrote in Cinema Scope: “The protagonist of Kaili Blues, Chen Sheng, is a small-town medical practitioner and ex-con. He bought his practice in Kaili, in southwestern China’s Guizhou province, with a small inheritance after his mother died while he was in jail. He’s not exactly a doctor; he’s more of a dreamer, a poet, and a traveller. In Bi Gan’s remarkable debut, winner of Best New Director prizes at Locarno and the Golden Horse Awards, it seems that only dreamers like Chen can see what’s real. He often falls asleep, when we hear examples of his surrealist poetry read in his flatly expressive voice — which, like his face, seems stiff but barely conceals emotional tensions roiling under the surface. The poems are in fact Bi Gan’s, from a collection titled Roadside Picnic (Lubian yecan), which is the Chinese title of Kaili Blues, after Bi’s original title (Huang ran lu, the Chinese name of Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet) was rejected by censors as too downbeat. These poems lead him, and us, into cinematic dream spaces where Bi’s camera animates a free, curious, and observant subjectivity — maybe a person’s, maybe a poem’s. Even if viewers don’t know exactly what’s going on, we can intuit the emotions, connections, routes, and channels of feelings that course through the film. This isn’t standard art-cinema-approved social realism: it’s a realer sort of realism, bringing us through sounds and images into direct contact with a vividly imagined dream world, but one that’s quite specifically grounded in details of place, biography, and community. [Source: Shelly Kraicer, Cinema Scope no. 65 2016]

“Rather than setting out plot in a somewhat artificially schematic manner, the film builds intricate skeins of narrative that connect all the main characters in complicated ways, with loops and paths that seem spontaneously but organically generated. Still, some clarity can be provided to aid the viewer. Nine years before the story proper begins, a rival gangster buries alive the son of Chen Sheng’s gang boss Monk, and also cuts off the son’s hand. The latter act being intolerable, Chen attacks and perhaps kills the rival, and then goes to jail. When he’s released, he finds that he has lost his wife Zhang Xi to illness. He also assumes responsibility for ensuring the safety of his half-brother Crazy Face’s son Weiwei. Crazy Face is a piece of work, and sells Weiwei (who is fascinated with timepieces) to a watchmaker, who takes him away to Zhenyuan. Chen’s senior medical colleague Guanglin had a lover or close friend named Airen from that town. When she learns that Chen is heading there to find Weiwei, she entrusts him with a mission: to find Airen and give him a cassette tape and a long-ago-purchased shirt.

Art House Chinese Films in the 2000s

“Go For Broke” (2001) , directed by former psychology professor Wang Guangli, depicts the lives a group of workers in different industries who are laid off from their job. The actors are real life workers, who wear their real life clothes and who are filmed in their real life hang outs. The film did well at American and European art houses.

“Balzac et La Petote Tailleuse Choinois” ("Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress", 2002), directed by France-based Dai Sijlie, is a coming of age story set in a poor village during the Cultural Revolution about two educated teenagers from privileged backgrounds who turn a poor peasant girl onto Western literature. It was one of the few films that is based on a best-selling novel written by the director. Dai, who has been living in France since 1984, was denied permission to shoot his Chinese-language films in China and instead has shot them in France and Vietnam

“Blind Shaft” (director by Li Yang,2003) was about a couple of ruthless grifters. working in the coal mines of Hebei province and Shanxi province. Much of the film was shot 700 meters below ground. Michael Berry wrote: A dark film that combines a gritty documentary style with a gripping edge-of-your-seat story, Blind Shaft also features a star-making debut for actor Wang Baoqiang. Li's second film “Blind Mountain” is a slow yet gripping story of a woman who is abducted and sold into labor in a remote village. [Source: RADII]

“Warrior of Heaven and Earth” (2004) by He Peng was described by the New York Times as “”High Noon” in the Chinese desert.” Set on the Silk Road in the 7th century, it combines American Western plot devices and character types with martial arts sword play and choreography with a some decapitation and sliced off limbs thrown in. He Ping also directed “Red Firecracker, Green Firecracker” (1994).

“Two Great Sheep” by Liu Hao (2005) wrote Stephen Holden in the New York Times is a “mild-mannered satire of hierarchal life in rural China” about a “dutiful peasant and his wife are rewarded for their generosity to the community by being entrusted with the raising if two foreign sheep of a superior breed...You can read this modest little comedy as either an uplifting fable about teamwork and good citizenship or as spoof of frightened society’s blind obedience to authority.”

“Tuya’s Marriage” by Wang Quan’an won the top award — the Golden Bear — at the Berlin Film Festival in 2007. It is a low budget film that examines the human and environmental cost of China’s rapid growth through a family of herders in Inner Mongolia who way of life is threatened by desertification. Tuya is housewife that lives with her family and 100 sheep in northeast Inner Mongolia. Her husband can no longer work as a result of an injury. He urges Tuya to divorce him and find a new husband so she can better take care of their family. Wang Quan’an's “Apart Together”, about a couple separated for decades by the Taiwan Strait, opened the Berlin Film Festival in 2010.

Art House Chinese Films in the 2010

“Dooman River” (2010) is a feature film by Zhang Lu. Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films wrote, “Lu Zhang Lu has made a career of exploring the ambiguous boundaries that define his Korean-Chinese heritage, perhaps no more explicitly than in this film, situated on the North Korean-Chinese border. Depicting the complex interactions between men escaping the PRK and the ethnic Korean Chinese who reluctantly take them in, it’s Zhang’s most accessible film, offering emotional payoffs while complicating notions of Chinese and Korean identities. Technically it’s a Korean-European production, which may explain why it’s been largely marginalized from discussions of Chinese cinema of the past year; but in no way should its relevance be in doubt.” [Source: Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

“Thomas Mao” (Xiao dongxi, 2010), directed by Zhu Wen, is a fictional tale about a Chinese farmer and a German artist; then it flips to a semi-documentary about a Chinese painter and a European curator. Zhu stages various confrontations between the Foreigner and the Chinese in a series of modes (comedy, science fiction, wuxia, documentary) and flips the stakes again and again, until the outside/inside distinction starts to blur and melt away. Kevin Lee of dGenerate Films wrote, “This is technically a state-approved production, having passed the Film Bureau and premiered at the Shanghai International Film Festival. But its irreverent, independent spirit is undeniable and unlike any other film that made it to official movie screens (the possible exception being Jiang Wen’s Let the Bullets Fly). Using everything from broad comedy involving animal sex to sophisticated CGI, Zhu Wen paints a lively, shape-shifting relationship between Chinese artist Mao Yan and German curator Thomas Rohdewald, who switch roles halfway through. Zhu Wen, a lover of opposites as seen in his past films Seafood and South of the Clouds, does a lot here with thematic face-offs: Chinese vs. foreign, urban vs. rural, educated vs. primitive. Probably the most playful Chinese film of the year, one that keeps you guessing from start to finish. [Source: Kevin Lee, dGenerate Films]

“Buddha Mountain” (directed by Yi Yu, 2010) won an award at the Tokyo International Film Festival in 2010. Fan Bing Bing won the best actress award the festival for her performance in the film.

Independent Films of 2012

“Egg and Stone" (directed by Huang Ji, 2012) is a coming-of-age film described as "an extraordinarily intimate and powerful debut film by a woman director about growth through and over a painful teenage as well as feminine experience., It won the Tiger Award for Best Feature Film at the 2012 Rotterdam International Film Festival. Shelly Kraicer wrote in China File, The film“is troubling rural tale (all too typical, Huang tells us) of a young woman’s sexual abuse at the hands of intimate acquaintances from her village. The film, though, is no typically dour Chinese miserablist indie (a genre Western festivals do too much to encourage and perpetuate). Huang bathes her film in vivid, saturated light and color, exhibiting something akin to that unstoppable life force that animates the heroines of Three Sisters in the face of unimaginable adversity. [Source: Shelly Kraicer, China File, January 17, 2013]

“Two of the best new Chinese films in 2012 were even more experimental in their approach. The first feature film of novelist Chai Chunya, Four Ways to Die in My Hometown) is a visionary masterpiece. Burying hisnarrative lines deep underground, Chai builds up a series of striking tableaux, hypnotically suggestive and pictorially spectacular. Two young women lose a camel, then a father. A retired shadow puppeteer meets a gun-toting tree thief. Storytellers and shamans organize a lost spiritual world that Chai wills back to life in deeply beautiful visual motifs whose meanings lie tantalizingly just out of reach.

“Emperor Visits the Hell”, a black and white film from Li Luo, is another kind of narrative experiment. Li takes a sharply satiric concept and makes it seem utterly natural and brilliantly comic. He relocates an episode of the Chinese classic Journey To The West to present-day central China, to Wuhan, where the Tang Dynasty Emperor Li Shimin of the novel is now a corrupt but aesthetically refined official. Ghosts and demons become the criminal gang leaders with whom Chinese officialdom formally and informally collude to share power and amass wealth.

“Judge Archer”, the second feature from novelist and martial arts practitioner Xu Haofeng, is a strikingly innovative wuxia (martial arts film). This independently produced but officially approved film is about a master archer who adjudicates disputes in the martial arts world. In it, Xu dares to redesign martial arts cinema for the current moment. He borrows from masters Chang Cheh and King Hu but forges an entirely new, transparent, and elegantly visceral style fusing action choreography with editing, cinematography, and narrative experimentation. Xu’s film gracefully embodies what Chai Chunya implies: that radical cinema can show how the living cultural traditions seemingly destroyed by China’s rush to modernize are not only still conceivable but imaginatively re-constructable and even necessary.

Art House Films in China in 2015

“Deep in the Heart” directed by Qi Yukun. Li Jingjing, Global Times: “While this film lacked a glamorous cast and a well-known director, this suspense film, Qi's first and costing only 1.7 million yuan ($270,000) to make, was a huge surprise. After the film quietly hit cinemas in October, word of mouth about its solid story and performances soon circulated among audiences, making it one of the top-rated suspense films ever. The sudden appearance of a burnt corpse disrupts the quiet peace of a small rural village. Soon after more mysteries begin to unravel. The white-haired head of the village comes in to clear up the chaos, but ends up getting involved in a complicated web of deception that is far beyond his control. Many audience members praised the film's Rashomon-style storytelling and structurally intricate plots.“"It's fortunate to see a director who really used his brain for his first movie," netizen Xiedu Dianying commented on movie.douban.com. Mtime rating: 7.9/10; Douban rating: 8.6/10. [Source:Li Jingjing, Global Times, January 5, 2016]

“The Dead End” directed by Cao Baoping caused quite a stir when it hit cinemas. Not only was the film from renowned director and screenwriter Cao Baoping, the mind behind previous critically acclaimed art house films The Equation of Love and Death and Einstein and Einstein, it also won Cao the best director award at the Shanghai International Film Festival in August. Meanwhile, the performances of the three leading actors in the film were so good and woven together that the three jointly claimed the Best Actor Award at the festival. "It's rare to see a Chinese crime film be that good. The case, the depth of the characters and the complex relation between them were all mezmorizing," netizen Taotao Taodianying commented on Douban. Mtime rating: 7.8/10; Douban rating: 7.9/10

“Saving Mr. Wu” directed by Ding Sheng: More attention-grabbing than big-name stars like Andy Lau and Liu Ye was the authenticity of the story. The film depicts the story of how police deal with a criminal over a period of 20 hours to save a star (Lau) who has been kidnapped. The story is based on the 2004 real life case of actor Wu Ruofu, who plays one of the police officers in the film. That case was widely talked about at the time, after which, Wu gradually disappeared from both large and small screens. However, Ding spent three months persuading Wu to work on this film about his kidnapping, which only added to its sense of realism. Mtime.com: 7.7/10; Douban rating: 8/10

“Ever Since We Love” (Li Yu, 2015) stars Fan Bingbing and is set in a Beijing Medical School in the ’2000s. Adapted from a bestselling book, it captures the fearlessness of youth that have grew up during China’s Opening Up period. Yalin Chi, of Cheng Cheng Films wrote:: Award-winning director Li Yu’s film adaption of bestselling writer Feng Tang’s novel about a male medical school student’s coming of age through romances with different women explores how economic imbalance and disparity in social rankings brought by China’s soaring economy along with changing gender roles intervene today’s romantic relationships. Li Yu enriches the original story with a female perspective, arguing modern Chinese working women have to cope with being sexually objectified when trying to rise in male-dominated world, which engages with the high exposure and controversial media persona of mega-star Fan Bingbing, the film’s female lead and Li Yu’s long-time collaborator. [Source: RADII]

A number of other art house and indie films came out that were not just critically acclaimed in China, but also made it onto shortlists or were awarded at international film festivals such as Cannes. These are “A Fool” by Chen Jianbin; “Red Amnesia” by Wang Xiaoshuai; “Mountains May Depart” by Jia Zhangke; “12 Citizens” by Xu Ang and “Mr. Six” by Guan Hu.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, IMDB, YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2021