DRIVING IN CHINA

On driving in China, David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “While inexperience is certainly a factor, Chinese motorists must negotiate more hazards than their counterparts in the industrialized world. Many pedestrians still behave as if the auto revolution in China never happened — wandering aimlessly into crosswalks, darting across eight-lane highways and loitering in traffic medians. Riders of motorcycles and bicycles often ignore traffic lights and weave in and out of traffic. Vehicle drivers are just as reckless. Motorists who miss an exit often throw their cars into reverse and back up — even on the freeway. Many refuse to stop or yield when making a right turn, forcing cars and people out of the way. Drivers routinely barrel down the wrong side of the street. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, April 20, 2011]

“Courteous driving is seldom rewarded. Stop at a zebra crossing for pedestrians and you could wait endlessly for the sea of people to part. Experts say a culture of caution is still years away. Although the Chinese can spend hundreds of dollars on driving school and must pass an exhaustive exam, many soon abandon any good habits they've learned because traffic rules are rarely enforced.”

To be a good driver in China one has to be brave. On rural roads, heavy trucks, buses and cars race towards oncoming traffic, forcing other vehicles onto the shoulders as they pass slower vehicles. If a car breaks down because the fuel line is clogged many Chinese will simply stick the fuel line in their mouth and suck out the gasoline-soaked clog and then spit fuel into the carburetor. When the writer Peter Hessler observed a Sichuanese driver do this and light a cigarette afterwards he sighed with relief when the driver didn't explode.

In the cities the streets are clogged with bicycles, motorbikes, cars, buses and carts. In heavy traffic it is not uncommon for impatient motorists to pull into a bicycle lane to make progress forward. Pedestrians are notorious for jaywalking disobeying walk signals. At intersections traffic officers sit in booths and switch the traffic lights by hand and shout insults at offenders out the window. In Shanghai, 2,000 unemployed people were hired to keep pedestrians in line at major intersections.

Dogs are not so used to vehicles and they are often hit and killed on the road. One question that many Chinese ask when someone tells them they hit a dog is, “Did you eat it? Sometimes when drivers hit a big dog they throw it in the trunk and cook it at home.

See Separate Articles: TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; AUTOMOBILES IN CHINA: GROWTH, POPULAR CARS, NUMBERS factsanddetails.com ; OWNING A CAR IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ROADS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; ROAD CONGESTION AND TRAFFIC JAMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler, Peter Berkrot, et al. Amazon.com; Driving toward Modernity: Cars and the Lives of the Middle Class in Contemporary China by Jun Zhang Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com ; “Decoding China's Car Industry: 40 Years” by Anding Li (2021) Amazon.com; Lonely Planet China" 16 Amazon.com

Bad Habits of Chinese Drivers

Chinese drivers have many bad habits, including grinding gears, accelerating too fast, driving too fast and recklessly, turning suddenly without signaling, speeding through intersections without slowing down, and steering all over the road. Some Chinese drivers don't yield to pedestrians, don't yield to ambulances, park in such a way as to block traffic, oblivious the fact they are in other people's way. They drive slow in situations when they should be driving fast and drive fast when they should be driving slow. Few people wear their seatbelts. Kids often run out in the street without looking where they are going.

Some Chinese drivers are very pushy, aggressive, inconsiderate and don't watch where they are going. After observing a van roar through a red light with its horn blaring, one Hong Kong trucker told the Wall Street Journal, "Coming from Hong Kong, you'd expect him to stop, if not for the red light then certainly for a truck 20 times its size. But here, Hong Kong logic does not apply." About 37 percent of drivers on the road in China didn’t know how to driver three years ago,

According to the Los Angeles Times On Chinese streets cars make U-turns in the middle of the road, bicycles ride on sidewalks and motorcycles play chicken with oncoming traffic. Eye contact acknowledges defeat. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times, September 18, 2016]

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, China “is a nation of new drivers, and the transition has been so rapid that many road patterns come directly from pedestrian life — people drive like they walk. They like to move in packs, and they tailgate whenever possible. They rarely use their turn signals. If they miss an exit on a highway, they simply pull onto the shoulder, shift in reverse, and get it right the second time. After years of long queues, Chinese people have learned to be ruthless about cutting in line, an instinct that is disastrous in traffic jams.”

“Drivers rarely check their rearview mirrors, perhaps because they never use such an instrument when they travel on foot or on bicycle. Windshield wipers are considered a distraction. So are headlights. In fact the use of headlights was banned in Beijing until the mid-eighties, when China officials began going overseas.”

“People honk constantly...In a sense honking is as complicated as the language. Spoken Chinese is tonal...Similarly, a Chinese horn is capable of at least ten distinct meanings. A solid hooooonnnnkkk is intended to attract attention. A double sound — hooooonnkkk hoooonnnnkk — indicates irritation....There’s the stuttering, staggering hnkhnk hnk hnk hnk that represents pure panic. There’s the afterthought honk — the one that rookie drivers make if they are too slow to hit the button before a situation resolves itself.

Chinese Driving Customs

Car culture is new to Chinese. The Chinese have not grown up with cars as many American, Japanese and Europeans have. They are not used to the idea of taking long car trips and do a lot of dumb things. A surprisingly number of Chinese lock their keys in their cars and forget to put gasoline in their tanks. Students at driving school have to be taught how hold the steering wheel.

A rich Chinese woman in Vancouver, Canada told the The New Yorker: When I am driving here and need to make a turn, I turn on my signal light and do it. It’s the most normal thing in the world. When I first drove in Asia, I flashed my signal and immediately people, instead of slowing down, all sped up to cut me off. It was so maddening, and then, after a little while, I became like everyone else. I never signal when I turn in Asia. I just do it. You don’t have a choice.” [Source: Jiayang Fan. The New Yorker . February 22, 2016]

Rental cars are routinely returned with dented bodies and wrecked bumpers. The rental. agencies usually say no problem...they have insurance. One just has to write an accident report and put a chop on it. To rent a Jetta in China cost about $25 a day. An enormous amount of paper work is required that includes a lengthy inspection of the car to make a note of all dents and scratches on the car and marking them n a diagram. The tank is often less than half full when the driver pucks up the car and the driver required to return the car with about the same amount of fuel.

Many drivers wear white, cotton driving gloves. The attendants in Chinese gas stations are often women who give out such gloves free with a full tank of gas. Cars are seen as social rather than isolating vehicles. Many Chinese belong to car clubs and a car is seen as a way to meet up with old friends that would be inaccessible without one. Enthusiasm for driving is reflected in the popularity of “self-driving” vacations and drive-thru eateries. The number of McDonald’s with drive-thrus increased from 1 in 2005 to 115 in 2008. Drivers can compete in unofficial road races in the suburbs that attract hundreds of spectators.

Driving in Shanghai

On driving in Shanghai, Andrew Field wrote in his blog Squarespace: “It did not take long to accustom myself to the wide range of vehicular, cycle, and pedestrian traffic and the seemingly random ways that people navigated city streets...I quickly became used to the occasional brushups with other cars, usually the fault of a new driver. One time, a woman plowed into my Chevy from the right lane as if she had completely failed to notice its existence on the road. I became well acquainted with our insurance man, Gu, who miraculously appeared and whisked the car away to make the necessary repairs, returning it usually in around three days. I eventually gave up on trying to fix every scrape that appeared on the car.” [Source: Andrew Field, Squarespace, blog, July 31, 2010]

“In the spring of 2009, I even made a long journey southward to Ningbo, Hangzhou, and Thousand Island Lake with a few friends. Once out of the city I found that driving was both more simple and joyful on the new and immaculate highway system of Zhejiang Province, and I relished the experience of crossing one of the world’s longest ocean bridges, the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, on the way from Shanghai to Ningbo. It was quite an experience to be driving over the waters of the bay without seeing land for several kilometers in either direction, and from the perspective of the road, it was fascinating to witness the incredibly rapid development of one of China’s most economically developed provinces.”

On drivers in Shanghai, Field wrote: “At times it seems to be an all out battle for supremacy over the road with no quarter given. The "me first" mentality is very strong when it comes to driving etiquette or lack thereof. This in turn leads to far more accidents, which cause traffic delays ratcheting up levels of anxiety, leading to more fender-benders and so on in a vicious cycle. And people end up spending more time and money on the road and getting their cars fixed. But it is all worthwhile if one can shave that second off the road trip by cutting in front of another vehicle. This used to be true of lines here in China as well, such as the queues formed at a bank or a ticket counter. People have become far more polite about lining up since I first arrived in China in the 1980s. I suspect that over time, people in Shanghai will develop a more sophisticated sense of etiquette when it comes to driving. But who knows? Only time will tell."

Traffic Violations

Jaywalking is a common and dangerous practice in China. Pedestrians often don’t look where they are going and drivers are reluctant to stop for them.

In an effort to crack down on jaywalking in Shanghai, police there plan to post photos and videos of jaywalkers and problem cyclists and moped drivers in newspapers and on television to shame them pout of breaking traffic rules. Legal activists condemn the idea of using public humiliation as too severe a punishment for jaywalking and warned of defamation lawsuits against the police.

Police have found that giving speeding tickets is an easy way to make money. Some police who have stake in ticket profits have purchased and set up cameras in places where the posted speed limit suddenly drops without warning. The writer Peter Hessler said he got three $20 speeding tickets each time he took a road trip in the factory town area of Zhejiang Province, with the fines tacked onto his rental car bill.

New paved roads in the countryside make it easier for farmers to get their crops to markets and for rural kids to get to secondary schools.

Running’ Yellow Lights Made Illegal in China

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post: “Chinese authorities are attempting to improve the country’s difficult road conditions with a new law that will almost certainly worsen them. As of January, 2013 yellow lights were considered functionally the same as red lights. The fine for entering an intersection after a traffic light turns yellow is not the same as for “running” a red light. That fine has also gone up. [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, January 2, 2013]

“The new law says drivers in mainland China are legally obligated to stop at yellow lights as if they were red lights, which would seem to both defeat the entire purpose of having yellow lights and to invite regular catastrophe. A social media user named Sun Yixuan reported crashing into the car in front of him when it stopped suddenly at a yellow light, according to the South China Morning Post. “That car’s rear bumper and back doors were totally destroyed after the collision,” Sun wrote on social media. “Fortunately both drivers were fine.” Drivers who violate the yellow-light rule just twice are legally required to retake road training and an official exam. Given that motorists will often take just one or two short seconds to screech to a halt before crossing into a yellow light, more accidents seem likely.

“Even Xinhua, a major state-run media outlet, couldn’t hold back from criticizing the misguided law. “This new rule is against Newton’s first law of motion,” the news agency observed on its official social media account. Government bureaucracy is rarely known for its wisdom in any country, but this seems an extreme case. Chinese governance, despite its well-earned international accolades for the canny economic policies that helped lift hundreds of millions of its citizens out of poverty, has a much weaker track record when it comes to road rules. I’ve never driven in China, but the New Yorker’s Peter Hessler has, chronicling such habits as drinking beer during driver’s school and the non-use of windshield wipers. Given that the new yellow-light law will affect many urban, well-off or well-connected Chinese — for example, the editors at Xinhua — don’t expect it to last long.

Driving School in China

To get a license potential drivers must have at least 58 hours of instruction in a certified course that costs around $300 to $500, a considerable sum in China. The fee covers three weeks of classroom sessions, a month of behind-the-wheel training and three separate road tests. Explaining one reason for the rigorous testing procedure one inspector told the Los Angeles Times, "In China we have too many people. Too many drivers. We cannot let everybody on the road."

The diving instructors often have peculiar ideas. Hessler heard about one instructor that insisted his students start off in second gear. Another didn’t like his students to use their turn signals because they distracted other drivers. Another sat in the passenger seat and adjusted the rear view mirror so it faced him.

Most driving schools advance students through three stages: the parking range, the driving range and the road. On the first days students are generally shown where the engine, battery and radiator are and practice screwing and unscrewing the gas cap.

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, Student drivers “had been instructed to honk whenever they pulled out, or made a turn, or encountered anything in the road. They honked at cars, tractors, and donkey carts. They honked at every single pedestrian. Sometimes they passed another car from a driving school, and then both vehicles honked happily as if greeting an old friend. At noon the class had lunch at a local restaurant, where everybody drank beer, including the coach, and then they continued driving. One student told me that a day earlier they got so drunk that they had to cancel the afternoon class.”

When foreigners say to Hessler that he is crazy for driving in China he tells them, “I can’t believe you get into cabs and buses driven by graduates of Chinese driving courses.”

Driver's Licenses in China

Many people who go through all this and pass the driving test still can't drive because they can not get licenses for their cars or can not afford a car. Many people never even attend driving school or take a driving test. They simply buy their driver’s licenses.

In Shanghai, only about 80,000 of the 200,000 people that get a driver’s license every year can actually buy a car. One 28-year-old kindergarten teacher told the Los Angeles Times, “My dream is a small car, maybe the Chinese-made QQ or the Volkswagen Polo, because they are so cute and relatively more affordable. But everything is too expensive. For now I have no chance at all to practice driving.”

May people obtain their driver license on the Internet.

On driving with a new driver Hessler wrote, “Twice I had to yell to keep him from passing on blind turns; another time, I grabbed the wheel to prevent him from veering into a car. He never checked the rear view mirror, he honked at everything that moved. The absolute lack of turn signaling was the least of our problems. He came within inches of hitting a parked tractor and he almost nailed a cement wall.”

Chinese Driving Tests

Prospective drivers in Beijing are required to pass a medical check up, take a written exam, complete a technical course and pass two driving tests. Foreigners who want a Chinese licence have t pass a special foreigners test, which often involved nothing more than starting a car, driving 50 meter on a road with no traffic, and pulling over and turning off the car. [Source: Peter Hessler, the New Yorker]

The driving tests in China can be very hard and the criteria for getting a license can be quite arbitrary. In Shanghai, people who are too short, color-blind, suffer for nervousness or high blood-pressure, have trouble jumping are routinely denied the privilege to drive. Some are rejected because their thumb is not the right shape, or they are missing a finger or they can’t hear well in one ear. One driver who was not allowed to take a driving test because she was less than five feet told the Los Angeles Times, "All I want to do is drive a small car, not a big truck. I had no idea they had this rule."

The Shanghai driving test includes lifting weights to show hand strength, flexing fingers and jumping to show dexterity, having one’s blood pressure checked, pushing buttons with one’s hands and feet to check responses to visual and auditory stimuli and placing one’s head in a dark closet with a blinding headlight to see how well one’s vision adjusts to light.

In drivers education students learn various tasks and do them over and over. There is little preparation for actual city driving. One of the most difficult parts of the driver’s test is the single plank bridge tests, which simulates crossing a bridge in which there are only places for the tires to go.

Chinese Driving Test Written Exam

Drivers have to take a tough written test and get a score 90 percent or better to get a driver’s license. One question goes: When a vehicle overturns slowly and jumping out of the vehicle is possible, the driver should jump — A) in the driving direction; B) in the overturning direction; C) in opposite direction o f the overturn; or D) to the overturning side.

The following are some questions that Hessler noted from the driving test in Beijing .

During the evening, a driver should:

a) turn on the brights

b) turn on the normal lights

c) turn off the lights

When overtaking another car, a driver should:

a) pass on the left

b) pass on the right

c) pass wherever, depending on the situation

When driving through a residential area, you should:

a) honk like normal

b) honk more than normal in order to alert residents

c) avoid honking, in order to avoid disturbing residents

[Source: Peter Hessler The New Yorker]

If your car breaks down atop the tracks of a railroad, you should:

a) abandon it there;

2) find some way to move it immediately;

or c) leave it there temporarily until you can get somebody to repair it.”

When trying to save a person who is on fire, the wrong response is:

a) Use sand to cover him.

b) Try to extinguish the fire on his clothing as quickly as possible.

c) Spray cold water on him.

d) Take off his burning clothes. (Answer: A)

Driving Test for Foreigners in China

Questions on driving tests for foreigners in China include: ) If you have to suddenly jump out of an overturning vehicle, in which direction do you jump? And once you hit the ground, what’s the best way to roll? 2) When your car is suddenly plunging into water, what’s the best way to escape? Do you immediately open the door and jump out? Wait until the car hits the water and then open the doors? Stay inside and call for help? Or use your feet to smash the windshield? [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, April 2, 2012]

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post: “The computerized test, available in English, Arabic, French and several other languages to foreign residents who want to obtain a Chinese driver’s license, gives 100 randomly generated questions from a seemingly endless list. The topics include arcane traffic signs, police hand signals, and the amounts of various fines and penalties. To pass the test, a would-be driver needs to answer at least 90 of the 100 questions correctly, and many test-takers fail on the first few attempts.

“It’s a test that assumes that the motorist might encounter pretty much anything on China’s increasingly clogged and lethal roads, and that includes head-on collisions, tire blowouts and treating injured and bleeding passengers at the scene of a wreck. There are questions on the proper way to carry an injured person in a coma (sideways, head down), the best way to stanch the bleeding from a major artery and how to put out a passenger on fire (hint: Do not throw sand on the victim).

“And there’s an array of questions about mind-boggling penalties for all sorts of infractions, many of which seem to include fleeing the scene of various vehicular crimes — suggesting that the transport control department of the Public Security Bureau has pretty much seen it all. For example, causing a minor traffic accident and running away could get you less than 15 days in jail. But running away after causing serious injury or major property damage will get you three years behind bars. Running away after causing a traffic death brings a prison term of seven to 15 years.

“There are, for example, questions about what to do when encountering an old man riding a bicycle on the road, a bike rider coming in the opposite direction, a blind man walking down the road or a drunk pedestrian. There are also several animal-related questions: what to do when encountering a flock of sheep (“drive slowly and use the vehicle to scare away the flock”) and someone herding animals (reduce speed, keep a safe distance). However, when discovering animals “cutting in on the road,” the correct response is to “voluntarily reduce speed, or stop to yield.”

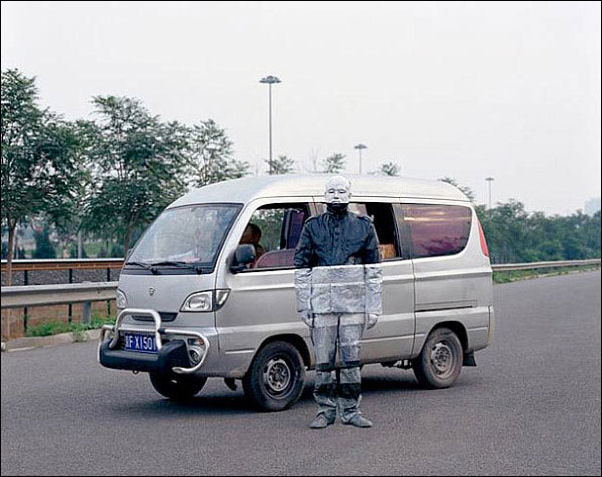

Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist

Peter Hessler's Country Driving

On Peter Hessler's “Country Driving” Andrew Field wrote in his blog Squarespace: “Country Driving is about Peter Hessler’s various experiences in China since the early 2000s, loosely organized around the subject of driving. The book is divided into three sections. In the first section, he describes his experiences driving out to remote areas of western China to research an article on the Great Wall for the National Geographic Magazine. The second section focuses on the village of Sancha, located near the Great Wall north of Beijing, where Peter and a friend rented a house that served as a weekend writing retreat. In the third section, he travels to a factory town in Zhejiang, where he becomes friendly with the bosses and workers of a bra ring factory.” [Source: Andrew Field, Squarespace, blog, July 31, 2010]

Throughout the book we learn plenty about what it is like to drive in this country and how rapidly the road and highway system is developing and how that in turn is changing the communities that become part of the national road network...Personally I feel that this is his best book yet....Book three reveals a more modest and focused Peter Hessler, more confident of his skills in the language and culture, but less prone to overgeneralizations about the people and country. At least, one feels that the general statements he does make about China are hard earned, if not always on the mark. Yet overall what I felt about this book was that it was a far deeper and more nuanced portrayal of China than his earlier books, not to mention those published by a myriad of China heads today. The main reason is that Peter is astonishingly good at bringing us into the intimate lives of a wide range of people. He has a real knack for befriending people and drawing out their most personal stories, a quality that was evident in his first two books, but not to the degree we find in his third.

In this respect, I found his second section, on the village in Sancha, to be among his best writing on China yet. Over a span of several years, he befriends one of the characters in the village and becomes a surrogate caretaker of his son, driving him to school and one time to the hospital in an incident where his kindly intervention was obviously of great benefit to the boy and his family. ..Peter’s intimate portrayal of the people of Sancha and their transformations over the years was one of the best accounts I’ve read of village life in China in recent years.

Image Sources: 1) University of Washington; 2, 9, 10) Beifan.com 3, 5 ) Nolls China website ; ; 4) Mongabey ; 6) CIA; 7) Gary Braasch; 8) Julie Chao ; Liu Bolin, China’s Invisible Man artist, Global Times Chinese: photo.huanqiu.com ' Amazon; Wiki Commons, Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022