URBAN TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA

Shanghai maglev

Chinese city streets are dominated by a chaotic mix of cars, trucks, buses, pedestrians, bicycles, motorscooters, buses and other various kinds of motorized and non-motorized small vehicles. The number of cars and trucks is increasing everyday and some cities are already choking in exhaust fumes and traffic jams.

China is in a race to build mass transit systems before its cities are engulfed by cars. As of 2009 at least 15 cities were building subway lines and dozens more were planned. Foremost among the ongoing projects is the one in Guangzhou where 60 massive tunnel machines and workers — working in 12-hour, five-day- a-week shifts — work around the clock, often in very hot conditions, to build one of the world’s largest and most advanced subway systems.

In 2013, China pledged to ease traffic congestion by making public transport account for 60 percent of all motor vehicle use in towns and cities. Bloomberg reported at that time: The government will support the development of environmentally friendly urban transport systems and offer tax breaks and fuel subsidies for mass-transit vehicles, according to a statement by the State Council, or Cabinet. [Source: Bloomberg News, January 7, 2013]

“As many as 300 million of China’s 1.4 billion people will move from the countryside by 2030 to join the 600 million already living in cities, according to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates. Traffic congestion and worsening pollution is forcing the government to improve public transport to cope with the influx.“As China’s urbanization accelerates, the development of urban transport faces new challenges,” the State Council said. The government “must prioritize the development of public-transit systems to ease traffic congestion, transform urban transport, improve people’s quality of life and improve the provision of public services,” according to the document.

“Beijing put four subway routes into operation in December 2012, bringing the number of lines in the Chinese capital to 16. The city, with a population of more than 20 million, already caps the number of new auto registrations and limits the use of private vehicles on designated days based on their license plate numbers. The government is planning to build a road-congestion charging system, the city’s transport commission said in August. Shanghai, Guangzhou and Guiyang are among cities that also impose restrictions on vehicle ownership. Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi province, broadened traffic controls from January 1, banning vehicles deemed heavily polluting based on their emissions from inside the city’s second ring road.

See Separate Article TRANSPORTATION IN BEIJING: SUBWAYS, BICYCLES, TAXIS AND ROADS factsanddetails.com ; TRAINS. LONG-DISTANCE BUSES AND AIRPORTS IN BEIJING factsanddetails.com ; TRANSPORTATION IN SHANGHAI factsanddetails.com ; GUANGZHOU TOURISM, ENTERTAINMENT AND TRANSPORT factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Handbook on Transport and Urban Transformation in China” by Chia-Lin Chen, Haixiao Pan, et al. Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler, Peter Berkrot, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet Transportation” (1991) by Editors: Zhang Ying etc. Amazon.com; “Chinese Junks and Other Native Craft” by Ivon A. Donnelly and Gareth Powell Amazon.com; “The Great Ride of China: One Couple's Two-wheeled Adventure Around the Middle Kingdom” by Buck Perley Amazon.com; “Finding Compassion in China: A Bicycle Journey into The Countryside” by Cindie Cohagan Amazon.com; “Dad's Bicycle: Journey of A Chinese Family” by Helen Wang Amazon.com;

Issues with Mass Transit in China

Passengers picking fights with bus drivers, often while the vehicle is moving, due to missed stops or other grievances, is an issue in China. In one incident in Chongqing in October 2018, a driver careered off a bridge, killing himself and over a dozen passengers. People have called for better protection for drivers, as well as heavier penalties for unruly passengers.

Efforts to build a Guangzhou subway system began in 1965 but workers gave up after 10 feet after striking granite. Attempts in 1970, 1971, 1974 and 1979 also ended in failure. Planning for the system under construction now began in 1989. Construction costs were around $100 million a mile, including land acquisition charges, compared to $2.4 billion a mile for new lines in New York.

It is not clear who will win the battle between cars and mass transportation but Chinese cities lack expensive parking and tolls on bridges and tunnels like those in New York City that discourage driving. While new subway lines are being built new suburban development are opening up that are nowhere near subway or train stations. People that can afford cars prefer the convenience of a 10 minute car commute over a 40 minute train ride.

Subways in China

Beijing’s subway became the largest in the world in the mid 2010s. Around 16 million Shanghaiese use that city's public transportation system everyday to get to work. Sometimes people wait in long lines to get on overcrowded public buses. In the 1990s six or seven million people rode their bicycles everyday in Shanghai but not so anymore.

A total of 36 cities in China either have or are constructing rail-based public transport systems. As of 2010, there were about 60 subway projects in more than 20 cities. China can build these kinds of transportation systems easier than the United States because the government owns the land, labor is cheap and protests against the system can not be organized. The Canadian company Bombardier produces subway and light rail cars in China.

Subways are being built in lesser known cities and even second- and third-tier ones. As of 2010, more than 30 cities had started building or submitted proposals for new metros. Shenyang hopes to open its first 50-kilometer subway line in October 2010 and have 11 more lines — creating a system longer than 400 kilometers, longer than New York City’s — ready in the coming years. The cost of the first line is around $2.9 billion. The cost for the entire system is expect to be around $24 billion.

China's first subways opened to traffic in Beijing in 1970, and Tianjin in 1980, respectively, and subway systems were planned for construction in Harbin, Shanghai, and Guangzhou beginning in the 1980s. In its first phase, the Beijing subway system had 23.6 kilometers of track and 17 stations. In 1984 the second phase of construction added 16.1 kilometers of track and 12 stations, and in 1987 additional track and another station were added to close the loop on a now circular system. In 1987 there were plans to upgrade the signaling system and railcar equipment on seventeen kilometers of the first segment built. The subway carried more than 100 million passengers in 1985, or about 280,000 on an average day and 450,000 on a peak day. In 1987 this accounted for only 4 percent of Beijing's 9 million commuters. The Beijing subway authorities estimated that passenger traffic would increase 20 percent yearly. To accommodate the increase in riders, Beijing planned to construct an extension of a seven-kilometer subway line under Chang'an Boulevard, from Fuxing Gate in the east to Jianguo Gate in the west. The Tianjin subway opened a five-kilometer line in 1980. The Shanghai subway was planned to have 14.4 kilometers of track in its first phase. [Source: Library of Congress, 1987]

The Guangzhou system opened in 1999 and has about 200 kilometers of track. Shanghai metro, opened in 1995 and is almost as big as the system in Beijing.The Shenzhen metro opened in 2004, initially with two lines, 19 stations, and 21.8 kilometers of track. Subway and light rail systems have alse been built in Chongqing, Nanjing, Chengdu and Qingdao. Metro transit in Hong Kong is covered by the privately operated Mass Transit Railway, which opened in 1979 and has six metro lines with 50 stations.

In 2012, $300 billion was allocated to build underground railroads in 34 cities over the next five years. According to Bloomberg: “The National Development and Reform Commission last month authorized the construction of 456 kilometers of subway in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, involving initial investment of 63.7 billion yuan ($10 billion) and has allowed similar projects in cities including Fuzhou and Urumqi. Hangzhou, capital of the eastern Zhejiang province, in November opened its first subway line and plans to build another nine by 2020, according to a November 24 Xinhua report. [Source: Bloomberg News, January 7, 2013]

Rapid Growth of the Beijing Subway

“Urban rail-based transit is developing extremely quickly,” Beijing’s vice mayor Huang Wei told the Nandu Weekly, “we have accomplished in ten years what took developed countries over a hundred years to achieve.” [Source: Jared Hall, China Beat, July 12, 2011, Hall lives in Beijing and teaches Chinese and World History at the International Division of Peking University’s Affiliated High School. His blog is called Beijing Time Machine]

Jared Hall wrote in China Beat, “Indeed, since 2001, Beijing’s two-line 54 kilometer (33 mile) subway system has experienced staggering growth. Today, 14 lines are in operation, stretching 336 kilometers (209 miles). By the end of 2015, the city plans to open five more lines and extend another 40 percent in length, making Beijing’s, at least by some measures, the world’s largest subway system.”

“The cost of laying new underground track is staggering. Initial construction alone costs an estimated 500 million yuan per kilometer (or 48 million U.S. dollars per mile). By this measure it takes just 20 kilometers of newly laid track to exceed the city’s entire 2010 transportation budget of 8.92 billion yuan. None of this even takes into consideration operating costs or constraints on revenue, most notably the local government’s 2 yuan (0.31 dollar) cap on ticket prices.

Not all have been as impressed with what the Nandu Weekly slyly satirized as China’s subterranean “Great Leap Forward.” Safety concerns have escalated alongside the pace of construction. Since 2003, Beijing Subway has admitted three separate incidents of stations collapsing during construction, each resulting in worker fatalities. Public uneasiness has been further heightened by tragedies elsewhere, including the massive sinkhole that appeared above a subway line in Hangzhou that claimed dozens of lives in 2008. Concerns have also been raised over incidents of poor planning that have compounded minor problems and created major disruptions for Beijing residents. In one case earlier this year, occupants of a building adjacent to the Daxing extension of Line Four protested when trains passing on the elevated line rattled their homes. A subsequent investigation revealed the tracks had been laid too close to existing buildings, and that basic sound and vibration management technology had been scrapped to cut costs.

To fund its ambitious expansion program, Beijing Subway has had to look beyond ticket sales. State-owned banks have been part of the solution. Generous loan terms have provided the capital necessary to construct much of the new infrastructure. Even so, mounting debts have only worked to underscore the need for fresh sources of revenue. This has pushed the subway corporation into related sectors like vehicle manufacturing and advertising. If such moves appear harmless enough, others have exposed real contradictions with its public interest mandate.

Resistance to the Beijing Subway

maglev

The Daxing extension... was implemented without any community participation in the planning process, Jared Hall wrote in China Beat, “When inquiries from those affected were directed to the company, they were simply ignored. Of course, this high-handed approach to planning extends well beyond mass transit authorities. It is endemic among transportation-related initiatives ranging from road-widening to car registration, and reflects an attitude that permeates a much wider swath of the public and quasi-public sectors in China. At the same time, it is still striking to see how blatantly the corporation disregards voices from the precise population it pledges to serve. [Source: Jared Hall, China Beat, July 12, 2011]

Although residents only discovered engineering deficiencies after the line had begun operation, they swiftly developed a coordinated strategy to redress their grievances. Their tactics included a combination of petitions and visits to government offices, public demonstrations, as well as lawsuits directed against the subway corporation. This particular repertoire of actions aligns exactly with those described by You-tien Hsing in her discussion of urban households resisting demolition more broadly. Even while operating within the political constraints of the capital, residents’ ability to first draw press coverage and then to extract a commitment from the subway corporation to rectify the problem should warn against dismissing localized resistance to expansion as futile.

An elderly couple camped outside as most of the city took shelter from the winter chill. They were doused in gasoline, flanked by a box of matches and a coffin. A small crowd looked on solemnly as the pair read posters recounting their story. These were Wang Shibo’s grandparents, whose store on the southern end of the popular Nanluoguxiang shopping street had been slated for demolition to make way for a new station along Beijing Subway’s newly-extended Line Eight.

Wang Shibo and her family insisted they were driven to this bold, possibly risky, act of public protest because their entire family teetered on the brink of financial ruin. According to Wang, the family invested practically everything they had to renovate the small clothing shop. But when the subway corporation abruptly presented a notice of eviction, they were reportedly offered just two percent of their investment back in compensation. The very public confrontation with the subway corporation that followed attracted the interest of the international press and a delegation from the National People’s Congress. The shop was torn down two weeks later, but not before an agreement was quietly reached with the family.

Nevertheless, some have persisted in dismissing resistance to subway expansion as narrow-minded. This is partly because conflicts appear to emerge in the form of individuals or small groups defending what might be characterized as “private interests” staking claims against the subway corporation, an entity charged with promoting the “public interest.” This contrast is sharply apparent in press accounts and online chatter deriding holdouts against demolition as “nail households” or “tigers blocking the road to progress?. The subway corporation itself defends cost-cutting measures and meager compensation rates by citing the immense cost associated with such an infrastructure.[Source: Jared Hall, China Beat, July 12, 2011]

Real Estate Developments, Land Seizures and the Beijing Subway

Jared Hall wrote in China Beat, “The subway corporation, making use of its mandated public authority, has seized scarce urban plots and large tracts of suburban land. Those with previous land-use rights are compensated—“often at below-market rates” — and the land is sold later to developers at a considerable profit. The scale of this practice is difficult to measure, but its results are evidenced by sleek luxury condos and high-end shopping plazas erected on land formerly cleared for subway construction.

Beijing Subway is hardly alone in this game of property speculation. Last December, Shanghai Metro was called out for seizing over 35,000 square meters (8.6 acres) of land to construct a 603 square meter (0.1 acre) station in Jing’an District. Not long after, an office complex was erected on the site zoned as “municipal utility.” Wang Chengli, a professor researching urban transportation at Central South University in Changsha, chided metro operators across the country for “being led by the nose by developers.” He pointed to local officials as complicit in the practice, with some even going so far as to “operate ministries for profit.”

Despite being intentionally kept in the dark, those with pre-existing land-use rights have hardly been blind to the yawning gap between the compensation offered and prices quoted for newly built housing units. After all, it is this very price disparity that prevents retirees or other low-income residents of the Old City (the central area bounded by the Second Ring Road) from finding new housing remotely close to their original neighborhoods in the city center. Facing the break-up of communities and two-hour commutes to jobs or senior health check ups, resistance against evictions has been understandably robust.

TEB — China’s Traffic Straddling Bus

To relieve traffic in congested urban areas, China experimented with so-called “superbuses” — vehicles which could hold hundreds of people and travel on rails, straddling two lanes of traffic, allowing passenger vehicles to drive underneath them. Tracks for the buses was laid in the northeast city of Qinhuangdao and testing with passengers took place in the mid 2010s. Three Chinese automakers were initially commissioned to produce the buses which ran on both electricity and solar power. There were plans to lay 80 kilometers of track in Beijing with the buses reducing congestion by 30 percent in some places. Among the obstacles that needed to be overcome were the construction of elevated bus stops and special traffic signals. Only small and mid size vehicles could pass below the buses; other vehicles were banned on roads using the buses.

The idea was first introduced in 2010 and later given the name Transit Elevated Bus (TEB). Engineers of early prototypes boasted the vehicles could carry as many as 1,200 people per trip and a project could be completed within 12 months. Describing one prototype proposed by Shenzhen Hashi Future Parking Equipment Co., Ltd, , BGR reported: “the model looks like a subway or light-rail train bestriding the road. It is 4-4.5 meters high with two levels: passengers board on the upper level while other vehicles lower than two meters can go through under. Powered by electricity and solar energy, the bus can speed up to 60 km/h carrying 1200-1400 passengers at a time without blocking other vehicles’ way. Also it costs about $74 million to build the bus and a 40-km-long path for it, only 10 percent of building equivalent subway. It is said that the bus can reduce traffic jams by 20-30 percent. [Source: Yoni Heisler, BGR News, May 25, 2016]

The first real-life Transit Elevated Bus (TEB) was 22 meters long and carried up to 300 passengers. It was demonstrated on a 300-meter track in Qinhuangdao, a coastal city in northeast China. CNN reported: The “project that caught global attention last summer when video emerged of the 26-foot-wide bus cruising over the top of cars during a test run. Billed as a potential answer to China's crippling traffic problems, the vehicle instead became the source of bottlenecks in Qinhuangdao. Cars traveling in both directions had to crowd together on the other side of the road to avoid the barely used tracks and idle bus. At the time of its test run, the bus was a new idea that drew a lot of people to the area, local resident Wang Jingzhou said in a video by China News. "Who would have thought that it would end up being demolished?" he said. Other residents have complained about the traffic problems caused by the abandoned bus and tracks. [Source: Sherisse Pham, CNN , June 23, 2017]

Beijing airport train

Demise of China’s Traffic Straddling Bus

After the first tests Jessica Meyers wrote in the Chicago Tribune: “The contraption straddles half of a four-lane road. Arctic blue and nearly a quarter the length of a football field, the bus-train hybrid looks like a prop built for a “Transformers” sequel. A passenger compartment hovers above the asphalt, designed so cars can zip beneath as riders glide above the gridlock. The TEB landed in this northern coastal city last summer. By early December, a brown film had settled on the bus’ windshield — until the carwash guys showed up with a platform ladder to scrub the 16-wheeler back to its former glory. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Chicago Tribune, January 31, 2017]

“Residents don’t know why the motionless vehicle still occupies one side of the street. The security guards hired to watch the bus rarely leave their heated hut. City officials can’t reach the company, TEB Technology. The doors to its Beijing headquarters are locked, although three disgruntled employees linger in hopes of getting paid. A project intended as a revolutionary solution to China’s traffic-choked cities now faces missing executives and allegations of financial wrongdoing. The town hates it. But was it a swindle or simply the recklessness of the Chinese business landscape, where projects start in a snap and then just as quickly evaporate? “Useless,” said Kong Lingchuan, 36, as he stocked shelves at his crammed grocery store across the street. “It would be better if someone just removed it.”

In June 2017, the project was officially scrapped. CNN reported: “Workers in Qinhuangdao tore out the tracks for the road-straddling vehicle with jackhammers and shovels this week. They're cleaning up the mess left behind by the project. Local authorities have now taken charge of removing the 330-yard-long test site and repairing the road, according to China News. A local government official told CNN she didn't know who was in charge of tearing up the tracks. She said her office has been unable to contact TEB Technology, the company behind the bus project that was supposed to have cleared up the test site last summer. While the tracks are being ripped up, the hulking bus will eventually be moved to a parking lot, China News cited an unidentified local official as saying. The vehicle's ultimate fate remains unclear. [Source: Sherisse Pham, CNN , June 23, 2017]

“Chinese state media began questioning the legitimacy of the project immediately after the test run, raising suspicions that the whole thing was a publicity stunt funded by a peer-to-peer lending program, a loosely regulated form of investment that has resulted in scams in China. Some local news outlets reported that TEB's backers were in financial trouble after promising investors overly ambitious returns. When CNN visited TEB's Beijing office in December, the company's director of development said its future plans were unclear because funding was being cut off.

Taxis in China

A typical Beijing cab driver in 2001 had to drive 12 or 13 hours a day, seven days a week, to earn $240 a month. Those that are wiling to work 15 hour a day could make $300 a month. In recent years the number of unregistered taxis has risen. Many drivers of registered taxis complain they have to work twice as many hours as a few years ago to make the same money. Taxis are only supposed to remain on the road for six years.

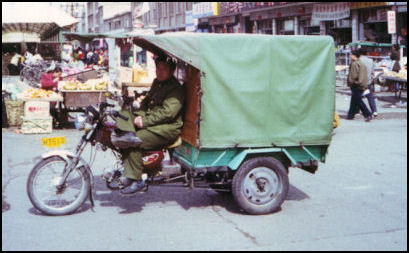

Three-wheel taxi

Taxi companies determine the wages and the working conditions of their drivers. In Beijing 300 companies control the profitable taxi market with an estimated 65,000 drivers. Drivers want a union but the government has blocked their efforts.

The taxi industry in Beijing began in earnest in 1992 when the economic liberalizations began to kick in. Taxi companies — most founded by local government bodies — took out loans to buy the cars. When the loans came due the companies demanded that the drivers buy the cars so they could pay the loans. Later the government nullified this arrangement and required the companies to buy back the cars. The companies took advantage of this and calculated the values of the cars at a discounted rate, forcing the drivers to take big losses.

The Beijing government is not the only local government that has taken advantage of taxi drivers. In the city of Dazhou in Sichuan, drivers used their life savings and went into debt to buy permits for $10,000 that allowed them to work in the city only to have the city require them to buy another equally expensive permit. Drivers staged protests in Dazhou and Chengdu and went ti Beijing to plead their case. They drivers made little headway. Some were sent to jail.

Some taxi drivers wear white gloves. Cab drivers in Beijing have their own radio show, "Hello Taxi," which features soothing music by Lionel Richie and John Denver, traffic reports, call-in anecdotes and car parts advertisements.

In 2008, there were several strikes involving taxi drivers upset over competition from unlicensed taxis. Taxi drivers were also upset by high fuel prices and increased rental fees for their cars. Dozens of police were called in to restore order when more than 100 cab drivers carrying bricks and rocks smashed windows of unlicensed taxis in Guangzhou in southern China.

Ride Sharing and Uber in China

According to ride sharing laws in Beijing and Shanghai, cars must have local license plates and drivers must be legal residents. Didi Chuxing is the main ride-hailing company in China. It has done its best to chase Uber out of China

Zheping Huang wrote in Quartz: ““Uber is having a hard time in China — and burning over $1 billion a year there, as CEO Travis Kalanick said in a recent interview. While it claims 30 percent of its trips come from China, the local ride-hailing market is dominated by Uber’s Chinese rival Didi Kuaidi. Didi nabs seven times as many daily bookings as Uber, operates in over 400 cities in China while Uber is just in 40, and has 4,000 employees while Uber has only 200 (plus a large army of underpaid and overworked interns). [Source: Zheping Huang, Quartz, February 17, 2016]

“On paper, Uber’s business in China looks like it is getting crushed by its Chinese rival. But Uber has carved out a special place in China. To many upper-class Chinese drivers like Fu, Uber acts more like a social platform than a ride-sharing app, connecting them to new friends. Tommy Wu, 27, from Shanghai, quit his dependable job as a government bureaucrat to become a full-time Uber driver. “There are 100 ways it is better than going to work,” Wu told me after he had just started full-time. He elaborated on two.

“First, he earns more for the same hours. As a civil servant, he used to earn just 4,300 yuan a month. Now he drives every day from 5pm to 10pm (most of that period is covered by an extra bonus for peak hours), and often three hours more from 7am to 10am. He estimated his monthly income at around 15,000 yuan as has already earned 2,800 yuan in four days excluding bonus. What’s more important, he said, is he feels more free. In the afternoon, Wu usually takes a rest at home — a nap or several rounds of online game League of Legends. Wu said his one-year-old daughter also “needs parents’ company.” He used to leave home before his daughter was awake and come back after she went to bed, which meant he could barely see her.

“Wu is now enjoying making more money, and hangouts with other Uber drivers, who he communicates with through a WeChat group. Among them, “190 centimeters,” or Fu, is one of his best driver friends. One time when Wu suggested in the chat group they all meet for a midnight snack,18 people turned up. When they were ready to leave at nearly 2am, they made a decision: They all signed simultaneously onto Uber’s driver app and put their phones on the table. “Whoever got an order first left first,” Wu said, “and the last one paid the bill.”

“As a latecomer to the Chinese market, Uber targets clients with “higher income stratum,” which at first meant expats, Tan said. That’s why he finds, after trying several apps, Uber helps him connect with the type of people and go to the type of places he may never have encountered though his predictable state-owned company job. Uber had no specific comment on the friend-finding phenomenon, but told Quartz that over 80 percent of Uber’s China drivers surveyed in mid-2015 were part-time. About 60 percent of those surveyed had three-year college or higher degrees, and drivers in Beijing had the highest education, with 5 percent having a Masters or higher. “Uber’s driver partners are overall a well-educated group of people,” Huang Xue, a spokeswoman for Uber China told Quartz by e-mail. The company endeavors to provide an “easy, comfortable, and safe” experience, and drivers are “stringently vetted,” she added.

See Separate Article SOCIALIZING AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Electric Skateboards in China

One-wheeled electric skateboards are a common sight in some Chinese cities. Jim wrote in Own Your Wheels: China is home to many electric skateboard manufacturers and a center for technological expansion. Demand for such devices in the Chinese soil is consistently rising. This is due to its large population and especially to its urban dwellers.” However, “they are not legal! The law simply prevents you from riding electric skateboards in most places! This may surprise most people considering that electric skateboards can be a way for people to beat traffic. However, with the nation notorious for large crowds and big vehicle traffic, safety is paramount. Officials have made it clear that the law stands this way in the interest of public safety. To avoid any punishments, you are advised to obey this law. [Source: ownyourwheels.com

One rider claimed he got a 75 RMB fine and while it isn’t much, it isn’t the case anymore. The fines have since gone up with the current standard fine being 200 RMBOpens in a new tab.. This punishment most times isn’t employed on its own, as you can also have your board seized. Confiscated skateboards is a very common punishment, where the authorities simply take your electric skateboard from you. If you ride an expensive electric skateboard, you wouldn’t want such to happen to you. It is unclear if you will get the electric skateboard back once it is seized. To simply be on the safe side, do not ride your electric skateboard on roadways.

While it is illegal to ride electric skateboards on roadways, some people still do it. The punishment doesn’t seem to be a deterrent as some people simply want to avoid traffic. This is why it is common to see people disregarding the law and riding electric skateboards on roadways. There are however places where you can ride an electric skateboard legally without getting in trouble. If you want to be on the safe side, these places include:

1) Within neighborhoods: The neighborhoods are closed off from major roads and the traffic here is less. Cars and other vehicles operate at reduced speed and more importantly, the police don’t frequent them. In many cases, the roads can be deserted, allowing electric skateboarders to operate freely. It isn’t exactly legal, but you should be able to operate here without any problems.

2) Bike paths don’t qualify as roadways so you should theoretically be able to operate here freely as well. Bike paths exist all across china, giving you ample room to ride your electric skateboard. In addition, the vehicles that operate here, do so at reduced speeds compared to roadways. This makes bike paths theoretically speaking, safer for electric skateboards.

3) Hutongs are narrow alleyways in a traditional Chinese neighborhood and are available in many parts of China. Hutongs are less busy than most roadways and don’t have large vehicles. The only kind of vehicles found here is scooters and others that aren’t legally classified as vehicles. Hutongs are also a safe option for electric skateboards as they operate with slow-speed vehicles.

Image Sources: 1) Columbia University; 2) BBC, Environmental News; 3, 7) University of Washington; 4, 5, 6) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Julie Chao, Wiki Commons ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022